3 minute read

Key Women

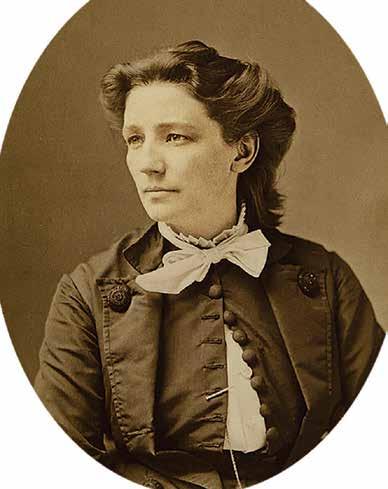

Victoria Woodhull

1838-1927

“Why is a woman to be treated differently? Woman suffrage will succeed, despite this miserable guerilla opposition,” wrote Victoria Woodhull, an immensely able, energetic, and free-thinking advocate for women’s right to both self-determination and the vote. She ran for president in 1870, sending this letter to the New York Herald: “I am quite well aware that in assuming this position I shall evoke more ridicule than enthusiasm at the outset. But this is an epoch of sudden changes and startling surprises. What may appear absurd today will assume a serious aspect to-morrow.”

Two years later, Woodhull ran as the presidential candidate for the Equal Rights Party, and Frederick Douglass, the famed civil rights activist who had been an attendee at the first convention for women’s rights in 1850, was nominated to be her vice president. She was reviled in the national press for her “radical beliefs,” such as believing that women should have the right to divorce their husbands. She was ridiculed in newspapers across the country; newspaper cartoonist Thomas Nast, however, who drew her as Satan in Harper’s Weekly, delivered a more ambiguous picture. In “Get thee behind me, Mrs. Satan,” she was “Mrs. Satan,” but the other woman in the cartoon is literally carrying a drunken husband and her children on her back. Obviously Nast could see some reason for her protest.

Woodhull was evicted from her home and she and her family slept in her brokerage office (she was a successful stockbroker); New York landlords were unwilling to rent to her.

She was a convener of the first Women’s Rights Convention in 1848, and wrote the “Declaration of Sentiments,” the position paper on women’s rights signed by attendees. From its conclusion: “Now, in view of this entire disfranchisement of one-half the people of this country, their social and religious degradation — in view of the unjust laws above mentioned, and because women do feel themselves aggrieved, oppressed and fraudulently deprived of their most sacred rights, we insist that they have immediate admission to all the rights and privileges which belong to them as citizens of these United States. In entering upon the great work before us, we anticipate no small amount of misconception, misrepresentation, and ridicule; but we shall use every instrumentality within our power to effect our object.”

Stanton was president of the National American Woman Suffrage Association from 1890 until 1892, and earlier was an active abolitionist. Unlike many of those involved in the women’s rights movement, Stanton addressed various issues pertaining to women: women’s parental and custody rights, property rights, employment and income rights, divorce, the economic health of the family, and birth control.

Her book “The Woman’s Bible” (1898) challenged the traditional religious position of women’s subservience to men. Stanton advocated a radical liberating theology, which stirred a great deal of controversy.

Sojourner Truth

1797-1883

Sojourner Truth (the name she created for herself) was born into slavery, and sold at auction at age 9. Her father had been born in Ghana; her mother’s parents were from Guinea.

She escaped with her infant daughter to freedom in 1826, and devoted her life to the abolitionist cause, helping to recruit black troops for the Union Army. Although Truth began her career as an abolitionist, the reform causes she sponsored were broad and varied, including prison reform, property rights, and universal suffrage. In 1851 Sojourner Truth gave her famous impromptu speech to a women’s rights convention in Akron, Ohio, concerning her rights as a woman (a later “dialect” version is unlikely to be accurate, as Truth’s first language was Dutch). A quote: “Then that little man in black there, he says women can’t have as much rights as men, ‘cause Christ wasn’t a woman! Where did your Christ come from? Where did your Christ come from? From God and a woman! Man had nothing to do with Him. If the first woman God ever made was strong enough to turn the world upside down all alone, these women together ought to be able to turn it back, and get it right side up again! And now they are asking to do it, the men better let them.”

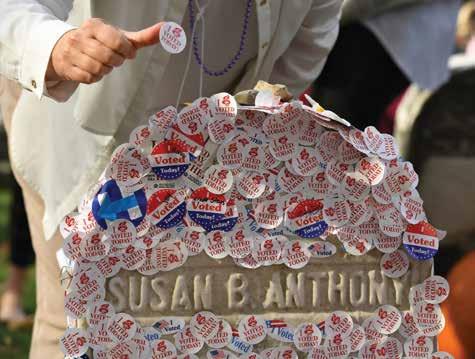

Susan B. Anthony 1820-1906

Susan B. Anthony had been raised in a Quaker household, and worked as a teacher. She later partnered with Elizabeth Cady Stanton and would eventually lead the National American Woman Suffrage Association. She cast her ballot for Ulysses S. Grant in the 1872 presidential election and was arrested and brought to trial in Rochester, New York. She and Stanton established the American Equal Rights Association in 1866, calling for the same rights to be granted to all regardless of race or sex. In 1868, Anthony and Stanton also created and began producing The Revolution, a weekly publication that lobbied for women’s rights. The newspaper’s motto was “Men their rights, and nothing more; women their rights, and nothing less.” It is Anthony’s tombstone that women decorate with their “I Voted” stickers — this tradition began with Hillary Clinton’s campaign for president, and continues still.

The Scandinavian Woman Suffrage Association

SWSA was founded in 1907 (when women won the vote in newly independent Norway) with help from prominent suffragist Ethel Edgerton Hurd. Led by Norwegian immigrant Jenova Martin, the group was first affiliated with the Minnesota Woman Suffrage Association, but it soon took its own course. Though open to men, the SWSA was mostly made up of — and exclusively led by — women. It charged no dues and thus welcomed many of all classes. Membership was limited to first- and second-generation Scandinavians, mostly Norwegian and Swedish. D

Ann Kelfstad is a Duluth freelance writer.