4 minute read

NO safe amount Advocates spread the word that drinking alcohol while pregnant is poison

BY ANDREA NOVEL BUCK

Brenda Caya helps people with Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorder and their families connect with resources they need to function in life. The Behavioral Health/FASD Family Advocate for The ARC Northland also works to educate health care providers, teachers and others about the need to talk to women of childbearing age about the damage alcohol can cause during pregnancy.

During her 18 years with The ARC Northland, the scope of the disorder has become better understood, the science regarding the stage of fetal development and damage caused at the time a pregnant woman drinks alcohol more exact, and the risk proven.

Even though the medical community doesn’t always say it strongly, Caya does: “Alcohol is a poison that goes through the mother into the developing fetus.”

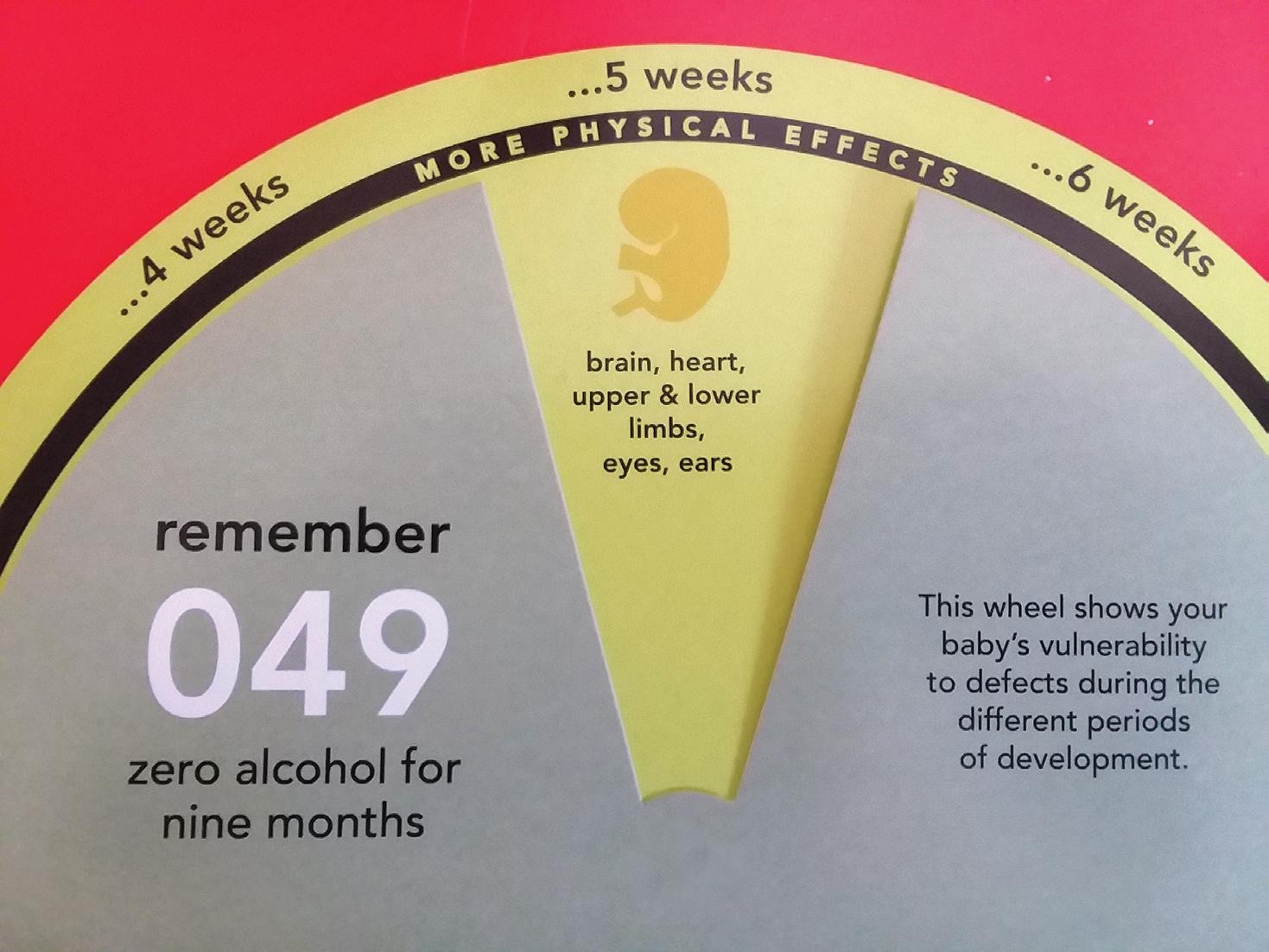

About 1 in 10 pregnant women report alcohol use, which equates to about 7,061 babies born each year in Minnesota with prenatal alcohol exposure, according to Proof Alliance, formerly MOFAS. The organization runs a “049” campaign with the goal that all women know there is no safe level of alcohol and no safe time to drink alcohol during pregnancy.

Caya reports that the Northland tends to be higher in diagnosed cases of FASD than other regions in the state. “We’re pretty at risk. People here tend to drink to party and get the inebriated effect.”

FASD and its consequences

Caya pulls out a copy of her educator’s Power Point presentation as she talks bluntly: “FASD is brain damage caused by prenatal exposure to alcohol … It’s lifelong. It’s permanent. They will have FASD all of their life.”

Physically, a person with FASD may have eyes more wide-set, ears that are lower, a philtrum that’s less pronounced (the dent above the top lip), or several other facial variances from their genetics. They may have a lower birth weight and a slower growth rate. They may have physical damage to other organs.

The huge impact is the brain is affected, Caya said. Primarily, a person’s cognitive processing is impacted — their ability to take in information, to process information, to apply information, and to remember information.

“They have a hard time connecting the dots,” said Laurie Berner, executive director of The Arc Northland. “They have a hard time learning cause and effect.”

Caya uses the example of a 3-year-old girl with FASD who is standing in a corner, her punishment for misbehaving. The girl has been told she can leave the corner once she says she is sorry. The girl can tell you that she can leave the corner when she says she is sorry. But she can’t make that connection to actually say she is sorry.

“They aren’t being defiant, but it looks very defiant,” Caya said of people with FASD. “Their brains can’t make connections. They can tell you what they need to do, but they can’t do it.”

At the low end of the spectrum, a person with FASD may have poor short-term memory. At the far end, a person’s functional ability will be half their chronological age, Caya said.

Helping FASD clients and their families

Often, communities work with individuals with FASD without knowing it — through special education services, mental health services, judicial proceedings. “A lot of people do not get diagnosed early on,” Caya said.

Assessment is important. “If you are aware of the challenges, the matches can be better.”

If someone suspects they or a loved one has FASD, The ARC Northland is a good place for referrals to diagnostic assessment, information, services and some direct help.

That help begins with the individual’s needs at that moment. The spectrum is so wide and so varied, Caya explained. One person may need little boosts such as a routine that helps them remember or coping strategies for their behavior. While another person may need supported employment or housing.

The ARC Northland runs a social support group called YAC where FASD youth, ages 14 to 25, can work on social skills, communication, money management, meal planning and other skills. It runs extreme parenting groups for parents and caregivers of children with emotional/behavioral disabilities and FASD specific parenting groups. Advocates help parents work with schools on their child’s education plans.

Parenting a child with FASD takes a lot of patience. “A lot of children with FASD don’t behave in ways that reciprocate love. The emotional pieces are disrupted. There’s no motivation to please parents,” Caya said. “We normalize behavior with FASD. We don’t give up. We do it in a different way.”

100 Percent Preventable

One of the toughest parts of Caya’s work — perhaps, what should be the easiest — is prevention. The ARC Northland has seen funding from the

1990s and 2000s drop off — even though nothing has changed about the disorder.

“Prevention is very hard to fund,” Berner said.

FASD is 100 percent preventable. And yet, 1 in 5 Minnesota women did not receive any message about alcohol use from their doctor or were told they could drink lightly or in moderation, according to 2013 statistics cited by Proof Alliance.

“We would like for people to know that there is a risk,” Berner said.

Caya said imparting that risk is much easier with mothers who are planning a pregnancy. But for young mothers, such as high school or college students, who weren’t planning a pregnancy and are already three months along, it’s difficult. She has shared her FASD Power Point to high school health teachers and sometimes even talked directly to eighth-grade students.

“The stigma, the shame is so great,” Caya said when a mother learns her child has FASD. “It’s so hard, the idea a mother could have done this damaging hurt to their child.”

— MDT

Andrea Busche, a professional journalist for 25 years, is a Duluth freelance writer and Youth Education Director at Temple Israel.

1 in 10 pregnant women report alcohol use, which equates to about 7,061 babies born each year in Minnesota with prenatal alcohol exposure