Did a black bear in Duluth nearly start a nuclear war?

By John Myers jmyers@duluthnews.comIt’s one of those stories that sounds too far-fetched to be true — that a bear outside the fence at the Duluth Air Force Base nearly triggered World War III and a possible nuclear holocaust.

But in recent years more accounts of the incident have surfaced that the legend appears to be true. Or at least much of it.

In October 1962, at the height of the Cold War between the U.S. and Soviet Union, American spy planes spotted Soviet nuclear missiles being installed in Cuba. Tensions mounted as both sides inched closer to war. On Oct. 22, all U.S. armed forces were placed on DEFCON 3, halfway to actual war, with President John F. Kennedy under pressure from his military commanders to strike first. The Cuban Missile Crisis had begun.

Here’s where the Duluth bear comes in:

On the night of Oct. 25, a sentry walking guard duty at what was then the Duluth Air Force Base (it has since been converted to an Air National Guard base) apparently spotted a shadowy figure climbing the fence.

Retired Adjutant Gen. Ray Klosowski of Duluth, an Air National Guard pilot who went on to command the 148th Fighter Squadron based at Duluth and later

the entire Minnesota Air National Guard, said the incident at the Duluth air base happened about a year and a half before he arrived. But he said it was still being talked about for years after he joined the base in 1964.

“It was at the height of the Cold War, the Cuban Missile Crisis, and there were probably 130 nuclear weapons on the base in Duluth at that time … so they took security very seriously,’’ Klosowski said.

Here’s where the details get sketchy, but reports say the sentry — apparently assuming it was an intruder, maybe a Soviet saboteur — shot at the intruder and immediately set off the sabotage alarm. The same alarm was connected to multiple alarm systems at bases in neighboring states.

Again, details remain unclear, but apparently the intruder turned out to be a black bear, which ran back into the woods unscathed.

The sentry apparently reported the misidentification in time so none of the aircraft at the Duluth base scrambled on alert. In Duluth, the situation had been diffused. But at Volk Field Air National Guard Base near Tomah, Wisconsin, something went wrong.

Somehow, instead of setting off the alarm that would let the base know intruders were present at another base, the Volk Field alarm went off that triggered a “scramble’’ alert to the pilots: Take off as fast as you can and prepare for imminent combat.

As part of the DEFCON protocol, 161 of the

Air Force’s F-106A Delta Dart interceptors had been moved from big air bases across the U.S. to several smaller bases, like Volk Field, to avoid Soviet detection. Volk was so small that it didn’t even have a control tower. Its missions were directed from the Duluth base.

The F-106s were intended to find and destroy Soviet bombers approaching the U.S. by firing a nuclear-tipped Genie air-to-air missile that

could knock out an entire squadron of bombers, Klosowski noted. The alarm that was sounding told those Volk Field pilots that Soviet bombers were on their way to drop their nuclear bombs on the U.S. As far as they knew, World War III was about to begin.

“They were literally sitting, ready to go, on the field, at the ready … that’s how high the tensions were for war. And you would never take off with nuclear weapons on board unless there was an imminent threat to the country,’’ Klosowski said.

Continued on page 4

But, according to several versions of the story, an officer at Volk Field decided to call the Duluth base to get confirmation that it was indeed a scramble situation. He was told it was a false alarm. At that point, the officer drove a Jeep out onto the runway, lights flashing, to stop the planes from taking off. (It’s not clear why he didn’t have a radio.)

As legend has it, that last-minute phone call may have prevented a black bear in Duluth from starting World War III and possible global nuclear annihilation.

Of course, it’s not certain or even likely the Volk Field planes would have gone very far north without being told the incident was a false alarm. But in those hectic days, nothing could be for sure. It’s also possible that, with many U.S. bombers in the air constantly at the time to avoid being destroyed on the ground, the U.S. interceptors might have fired their nuclear missiles at the wrong targets.

Later it was determined that, in the haste to wire new alarms at Volk Field as the Cuban Missile Crisis was unfolding, the installer had crossed wires,

mixing the intruder alarm with the scramble alarm. Much of the Duluth bear story remained classified and mostly under wraps for decades. It came out in declassified Air Force documents and was first reported by Stanford University professor Scott Sagan in his 1993 book, “The Limits of Safety: Organizations, Accidents, and Nuclear Weapons.” The incident is one of many Sagan reports in the book — fires, crashes, mishaps, miscommunications — when U.S. nuclear weapons may well have gone off if circumstances had changed ever so slightly.

Sagan interviewed Dan Barry, an Air Force pilot who was 27 back in 1962. He remembered scrambling at Volk Field, ready to take off into war. Barry remembers his plane being second in line to take off when he saw a truck speeding toward them, lights flashing, he told the La Crosse Tribune in a 2009 interview.

Barry, who in 2009 was living in Seattle, retired from the Air Force in 1986 as a colonel. After they were told to stand down, the pilots assumed something had shorted out the alarm system. Later, they heard rumor that it was a drunk airman trying to sneak back onto the Duluth base.

It wasn’t until Sagan called him that Barry learned it was a bear that started it all. As Sagan wrote in his book, the incident would almost be comical if it weren’t part of a pattern of near-misses over the years that could have led to nuclear war.

“That was serious business,” Barry told the La Crosse Tribune in 2009. “We’d never flown with a nuke on board. … It was really serious. I can remember almost expecting to see inbound nuclear missiles.”

For his part, Klosowski said the bear intruder and subsequent false alarm probably weren’t as close to causing a nuclear disaster as others assume.

“They would have been in contact with their command center. … They would have had to clear it with the Canadians. … There were other measures in place to prevent them from firing their weapons before they knew exactly what they were doing,’’ Klosowski said. “But I can imagine it was still nervewracking at the time.” u

Rick Lubbers

Every city harbors a collection of quirks, myths and legends that give it a unique essence, a character of its own.

Duluth and the Northland are no different.

We often talk about these stories in newsroom meetings or in everyday chitchat, and so we thought it would be fun to collect some and publish them in the April edition of DNT Extra.

Here’s a sampling of what you will read on these pages:

• Did a black bear in Duluth nearly start a nuclear war?

• Did World War II ace Dick Bong really fly through the Aerial Lift Bridge?

• What famous professional baseball players took to the diamonds of the Northland?

• What was it like living in Duluth during Prohibition?

The News Tribune newsroom enjoyed researching and writing these stories, and we hope you enjoy reading them.

Thank you for being a loyal Duluth News Tribune reader.

Rick Lubbers is the executive editor of the Duluth News Tribune. Contact him at 218-723-5301 or rlubbers@duluthnews.com.

2-4 6-9 10-11 12-13 14-15 16-18 19-21 22-23 24-27

Did a black bear in Duluth nearly start a nuclear war?

‘Evil resort’ dominated Canal Park

Richard I. Bong likely didn’t barnstorm bridge

Military housing put to new uses

Legacy of Denfeld class of ‘55 continues

Graveyards reveal unique history

Odd ideas in the northland

Fields of dreams Moonshine poured across Canadian border

Cover: News Tribune file photos

Cover designed by: Gary Meader / gmeader@duluthnews.com

Reporting by:

‘Evil resorts’ dominated Canal Park

By Tom Olsen tolsen@duluthnews.comLong before the Lakewalk, hotels, gift shops and eateries turned Canal Park into the tourism hub of Duluth, the lakefront area was far less inviting with its smattering of junkyards and warehouses.

The story of its transformation has been well-told in recent years, with resurfaced photographs showing old car parts and scrap metal lining the shore of Lake Superior. But long before that, in an era not so easily recalled, Canal Park was a thriving area of the burgeoning young city for even seedier reasons.

As shipping and rail traffic helped shape the city, a sizable “red light district” sprung up along the waterfront, offering a variety of vice for visiting workers and locals alike.

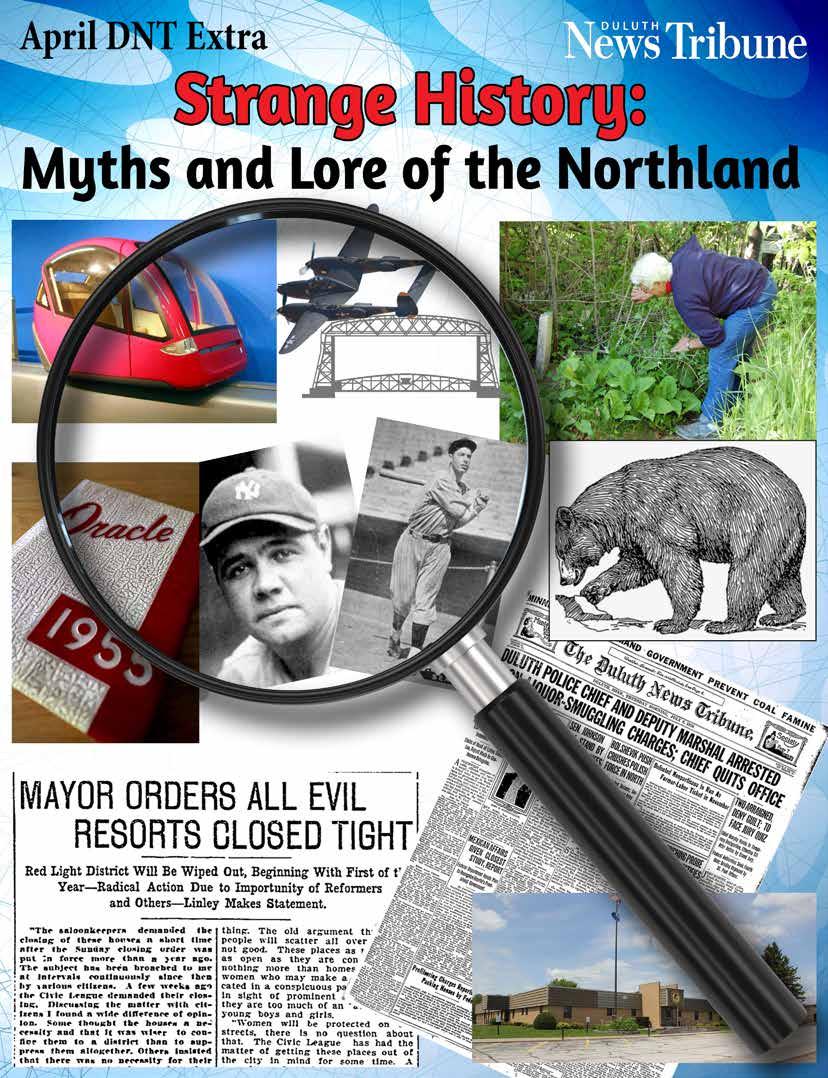

For decades starting in the late 1800s and continuing well into the 1900s, sensational headlines captured the debate over the scourge of brothels, which newspapers of the time commonly described using innuendos such as “evil resorts” or “houses of ill repute.”

Long before the construction of Interstate 35 divided downtown Duluth and Canal Park, the “Tenderloin” district was centered along Lake Avenue and St. Croix Avenue — today’s Canal Park Drive. It was the avenues’ shared alley, between Railroad and Sutphin streets, that became particularly notorious for featuring rows of ramshackle bordellos on either side.

Booze flowed freely, gambling debts were settled with fists, and young women roamed the streets outside the two-story clapboard rooming houses looking to entice men disembarking ships.

“In the very heart of the city, near one of the main thoroughfares, where thousands of people pass by day and night, there is an evil that is known to everyone,” the Rev. Arthur H. Wurtele said in a speech covered by the News Tribune in 1908.

“In the very heart of the city, near one of the main thoroughfares, where thousands of people pass by day and night, there is an evil that is known to everyone,” the Rev. Arthur H. Wurtele said in a speech covered by the News Tribune in 1908.

“It is the most flagrant flaunting of vice publicly before the people that I have ever seen. In no American or Canadian city that I have ever been in, has there been such substantial and luxurious looking buildings devoted publicly to vice, under police protection, as we have in Duluth.”

Police, politicians and judges tried at times to wipe the district off the map — issuing broad orders for establishments to shut down, enacting hefty fines and sending lawmen in for sweeping raids — though regulations often proved ineffective and it appeared an open secret that many in positions of power preferred to keep the district alive. Not exactly embracing its activities, some business leaders and political figures argued it was

Continued on page 8

A 1908 article recounted the efforts of the Park Point Civic Club to have the “evil resorts,” or brothels, removed from what is now Canal Park. (News Tribune archives)

nonetheless prudent to keep the red light district intact, under the watchful eyes of police, rather than dispersing the wickedness throughout town.

“That the red light district is a necessary evil in the life of a city was the argument most generally used,” the newspaper reported when the City Council voted to outlaw the establishments in 1908. “The (businessmen) said it would be impossible for the city authorities to prevent the springing up of a district elsewhere in Duluth if the evil resorts on St. Croix avenue are suppressed.”

Clergy members delivered sermons, and community groups called meetings to come up with

solutions — including a rather creative idea offered at a session hosted by the Park Point Civic League that summer.

“Suggestions were made after the service by prominent leaders of the league that an artificial island could be established a short distance up the St. Louis River, where the district would be isolated and of little annoyance to the community or temptation to the innocent young,” the newspaper reported.

The Duluth Police Department’s annual report in 1910 indicated 307 women were arrested that year, 54 for “common prostitution” and 12 for

“running houses.” There were 5,668 men arrested that year, too, but only two for operating resorts.

Even one of today’s longest-enduring symbols of Canal Park, Grandma’s Restaurant, comes with its own lore of Grandma Rosa Brochi, an Italian immigrant who supposedly welcomed lonely sailors to a bordello on the waterfront.

But Duluth wasn’t the only city grappling with public vice. As towns popped up on the Iron Range, so did brothels and saloons offering up hard liquor, gambling and prostitution to the miners and lumberjacks. Two Harbors had “Whiskey Row,” a rowdy waterfront grouping of some two dozen saloons and brothels.

“Anyplace where there is a large number of men, these things spring up around them,” local historian Todd Lindahl said in 2007. “It’s something that’s always happened.”

In Superior, the area around Third Street and John Avenue became famous for its redlight district. At least 85 prostitutes worked at establishments with colorful names as the St. Paul Rooms, Louise and Stanley’s, Indian Sadie’s and 314 John during the World War I era, late News Tribune journalist and historian Dick Pomeroy reported in 1997.

Complaints led to occasional raids and fines, but few serious consequences ever seemed to stem from the well-known activities, retired Superior police officer and author Alex O’Kash said in the same article. The women were often rounded up, but police didn’t seem to bother the johns.

“It was surprising. Generally, when there was a raid, there were very few customers present,” O’Kash said. “I think they were warned beforehand by law enforcement agencies.” u

Richard I. Bong likely didn’t barnstorm bridge

By Teri Cadeau tcadeau@duluthnews.comThe rumor that World War II flying ace Richard I. Bong once flew his P-38 through the Aerial Lift Bridge is very familiar to Briana Fiandt, curator of collections at the Richard I. Bong Veterans Historical Center.

“This rumor has been floating around forever, but we have never seen any proof of it,” Fiandt said. “We have extensive newspaper clippings about Maj. Bong, but I’ve never read any article that talks about him doing that.”

Fiandt said that for years she’s had people come in and say that a relative remembers seeing him fly under the bridge, but that she never talked to anyone who says they saw it themselves.

For decades, the story has been up for debate. In 2006, the News Tribune’s Chuck Frederick investigated the story and spoke with two people who claimed to have seen either the event itself or a photo of the flight in the newspaper the following day. (“Tales of daredevil pilots live on,” June 10, 2006). To this day, a clipping of

the photo has yet to emerge.

The person who claimed to have seen the stunt, John Hoff, said that he remembers seeing the P-38, nicknamed “Marge,” rise above the water fly toward the Alworth building downtown. He was 11 years old in summer 1944 and remembers seeing the flight from the window in his father’s office.

When he rushed to talk with the people in his father’s office about what he’d just witnessed, no one else claimed to have seen it. Hoff died in February 2013, taking his memory of the flight with him.

There are reports of other pilots flying through the bridge. These included flying boat “Lark of Duluth” in 1913, airmail pilot William Magie in 1924, “Dusty Rhodes,” a pilot and occasional bootlegger flew through in 1929, and Jack Daniel Brown, a Duluth Army Air Corps pilot who reportedly buzzed a P-38 by his brother’s house on Park Point and then barnstormed the bridge.

While evidence of Bong flying through the lift bridge is scarce, there are accounts of him flying under the Golden Gate Bridge. According to Fiandt, Bong always denied flying under the bridge, but he did admit to buzzing a friend’s house and flying low down Market Street while he was training in California.

“Gen. George Kenney said he had a report of Dick and two other pilots going under the bridge in ‘Dick Bong, Ace of Aces,’” Fiandt said. “But this is a memoir, not a serious historical work, so I don’t necessarily take everything Kenney writes at face value. I think he tended to play things up for a better story.”

Carl Bong also published a book of Bong’s letters and included his own memories called “Dear Mom: So We Have a War.” Carl also sticks to Bong’s story about buzzing a friend’s house, but that the other two pilots got into more trouble because they actually flew under the bridge,

while Bong did not.

Fiandt also said there were stories of Bong flying his P-38 over town, over the Walter Butler shipyards, over Marjorie Bong Drucker’s house and over his hometown of Poplar, Wisconsin, while he was flying around the country raising war bonds.

But as for Fiandt, she doesn’t believe the flight through the lift bridge happened.

“I think it would be incredible if there were proof of it, but my guess is that it didn’t happen,” she said.

Military housing put to new uses

By Peter Passi ppassi@duluthnews.comThe Aspenwood Condominiums off Arrowhead Road were built in 1960 to provide housing for U.S. Air Force base personnel. After the base closed in 1982, it was used as student housing by the University of Minnesota Duluth. A private company purchased it in 1986 and converted it to condominiums. This picture is from September 1997. (Josh Meltzer / News Tribune)

The U.S. Air Force constructed 60 buildings in 1960, providing 240 units of housing for military personnel at its Duluth base. At the time, the development was known as the Capehart Housing Area.

It occupies 114 acres of land below Arrowhead Road, accessed off Selfridge Drive.

For a short while, 5th District City Councilor Janet Kennedy’s family called Capehart home. Her late father, William Arnold Kennedy, a Korean War veteran, served in the Air Force. She said it was that service that first brought her family and many other people of color to Duluth.

“We have a lot of African heritage families who are here just for that reason. They were military migrants,” Kennedy said. “There was a sense of community. We were all pretty connected through the air base.”

When the Air Force closed its Duluth base in 1982, Capehart emptied out. The base closure, combined with the deactivation of a local air defense computer operation, eliminated about 1,375 jobs and dealt a painful economic blow to the community at a time when it was already reeling from U.S. Steel Corp.’s decision to shutter its mill in GaryNew Duluth. The Duluth base had an annual payroll of about $30 million.

In “Locating Air Force Base Sites: History’s Legacy,” Frederick J. Shaw wrote that Secretary of Defense Robert S. McNamara “emphasized efficiency and cutting waste in the defense establishment,” during his

tenure from 1961-68.

“Coupled with changing defense needs based on technological developments in weapon systems and a new strategic focus under President John F. Kennedy, this emphasis led to massive base closures not seen since the end of World War II,” Shaw noted. From 1961-72, the number of U.S. Air Force installations in the continental U.S. declined from 152 to 112.

Duluth’s base survived those cuts but was one of a handful of additional Air Force bases to close in the 1980s, joining the ranks of Fort Lee, Virginia and Hancock Field, New York.

Despite the departure of the U.S. Air Force, the 148th Fighter Wing of the Air National Guard has maintained a military presence in Duluth.

Following the

base closure, the University of Minnesota Duluth briefly converted Capehart to student housing, but in 1986 the school was outbid by a New Hampshire businessman, who offered $3.9 million to purchase the property from the U.S. government’s General Services Administration.

After sprucing up the place, the new owner remarketed Capehart in 1989 as Aspenwood, one of the city’s first condominium developments.

Barracks off U.S. Highway 53 that previously housed about 100 airmen in Duluth also found new life in 1983, when the facilities were converted to a minimumsecurity federal prison camp. u

Legacy of Denfeld class of ’55 continues

By Adelle Whitefoot awhitefoot@duluthnews.com

By Adelle Whitefoot awhitefoot@duluthnews.com

The class of 1955 is a legend around the halls of Denfeld High School. A plaque listing the graduates’ names hangs outside the auditorium. The plaque commemorates the $55,000 the class raised and used to create the Legacy Fund for the Greater Denfeld Foundation. The fund was created to help financially support the school and its students, Greater Denfeld Foundation President Jerry Zanko said.

Zanko, a 1969 Denfeld graduate, said the foundation solicits grant applications from teachers, coaches, advisers and other staff members. The proposals are then evaluated by a committee for approval.

The fund has helped pay for advanced-placement history books, graphic calculators, microphones for speech class, aprons for the culinary arts programs, microscope slides for biology, a computer for the robotics team and even shoes for the cross-country and track teams, Zanko said.

“The classroom things they purchase go a long way toward letting a teacher meet his or her obligation to teach their students in the best way possible,” Zanko said.

Teacher Angelo Florestano said the fund is known as the “Class of ‘55 fund” around the school, though it was never officially called by that name.

The Legacy Fund is now part of the Greater Denfeld Foundation Memorial Fund, which also includes the thousands of dollars raised every year from the Steve Anderson Legacy Golf Tournament.

Denfeld High School class of 1955 raised $55,000 to create the Legacy Fund for the Greater Denfeld Foundation to help financially support the school and students.

(Adelle Whitefoot / awhitefoot@ duluthnews.com)

Denfeld High School class of 1955 raised $55,000 to create the Legacy Fund for the Greater Denfeld Foundation to help financially support the school and students.

(Adelle Whitefoot / awhitefoot@ duluthnews.com)

Zanko said the memorial fund has received many donations over the years from alumni of all graduating classes. And one class of 1955 graduate, Harry Fisher, left a large sum to the fund after he died.

“It’s just really inspirational,” Zanko said of the pride Denfeld alumni have in their school.

That Denfeld pride was evident in the 1955 class song, which was written by two seniors, Mary Anne

Kertzscher and Marjorie Heckman:

“Our high school days are over, But we shall not forget Our alma mater, Denfeld, The many friends we’ve met. Much knowledge we have gained here, And victories we have won. The name and fame of Denfeld days Shall ever guide us on.” u

Graveyards reveal unique history

By Peter Passi ppassi@duluthnews.comThe Northland is home to a number of well-kept and stately cemeteries. But it’s also dotted with neglected and often forgotten graveyards that nevertheless harbor a treasure trove of knowledge for people interested in the region’s history, as well as for those who perhaps wish to trace their own family trees.

Throughout the years, efforts have been launched to reclaim and document many of the Northland’s lesser-known cemeteries. Lynn Reynolds has done extensive research on the subject, and in 1999 published her work, documenting more than 100 graveyards, in a collection called “A History in Stones: The Cemeteries of St. Louis County.”

The Twin Ports Genealogical Society also has been an active force, with its members working tirelessly to protect and restore sometimes-overgrown grave markers.

One place where the group has brought its resources to bear is the Scandia Cemetery, located next door to Glensheen Mansion, sandwiched between London Road and the shore of Lake Superior.

A common misconception is that the graveyard served as a repository for deceased members of the

affluent Congdon family who called Glensheen home. But that is not the case, as it predates the construction of the Congdon estate.

In a diary, which is now part of the historic mansion’s archives, Clara Congdon is said to have written: “I will have quiet neighbors,” referring to the neighboring graveyard.

The Scandia Cemetery is one of the oldest in Duluth, dating back to 1881, when it was started by members of the First Norwegian Danish Evangelical Lutheran Church, a house of worship long gone from the local scene.

Society members have worked to clear Scandia’s grave markers, rediscovering many that were completely overgrown.

Lakeshore erosion has proven a challenge, as well, with several gravestones perched mere feet from the water’s edge. News Tribune freelance writer

Kathleen Murphy reported in 2019 that some members of the genealogical society even were said to have heard of caskets found floating in Lake Superior following a particularly powerful storm in the 1970s, although she noted they were unable to verify the accuracy of those accounts.

Another often overlooked area graveyard is the Greenwood Pauper Cemetery off Rice Lake Road next to what had been the Cook Home, a work farm for the poor. It serves as the final resting place for nearly 5,000 destitute individuals who died between 1895 and 1947. The numbered graves were intended to serve as a guide to whom was buried where.

But poor record-keeping led to confusion, causing county and historic society members to

Continued on page 18

•Enhances root growth

•Helps soil drain in heavy rain and retain moisture in drought

•Gradually delivers nutrition

•Great for vegetable and flower gardens, potted plants, trees, lawn and tur f

abandon efforts to place names on individual graves. Instead, a single marker honoring all the dead has been installed in the center of the cemetery field.

In 2012, the St. Louis County Board officially declared the Greenwood Pauper Cemetery “inactive and historical,” taking steps to ensure it will remain undisturbed in the future, with county crews continuing to mow the grounds in an effort to hold back encroaching brush and trees.

Still another cemetery located well off the beaten path was documented by Lynn Reynolds in her research: the Roussain Graveyard near Fond du Lac, near the edge of Jay Cooke State Park. The cemetery draws its name from Francis Roussain, who purchased the land and surrounding property while employed by the American Fur Co. in the early- to mid-1800s, according to the late John Fritzen, a local historian.

Fritzen reported that Roussain offered up land for the cemetery, when the Lake Superior & Mississippi Railroad came to Duluth. The new line apparently ran through two pre-existing cemeteries, and Roussain agreed that any affected graves could be relocated to a fenced-in area on his land.

Odd ideas in the Northland

By Jimmy Lovrien jlovrien@duluthnews.comThere’s an 1993 episode of the cartoon TV show “The Simpsons” where a “Music Man”-esque salesman convinces the city of Springfield it needed to buy a monorail.

In the early 2000s, it almost happened in Duluth. From 2003 to 2005 — and one last time in 2011 — the on-again, off-again idea of Taxi 2000, a futuristic personal rapid transit system that would carry people around town on a monorail in three-passenger pods, was pitched by area developers.

At first, the potential route included a loop that would connect the Duluth Entertainment Convention Center, Canal Park and downtown. The cost grew from $60 million to $80 million, and attempts were made to secure state and federal funding and tax breaks.

With such a high price, a cheaper, half-mile, $22 million demonstration track at the Duluth International Airport to connect the terminal with remote parking options was also considered. (There have never been remote parking locations at the airport.)

It’s just one of many odd, outlandish and outright gimmicky plans that have been proposed over the years in Duluth.

Connecting Lake Superior to the Gulf of Mexico

For 100 years, dreams of a canal connecting Duluth to the Gulf of Mexico via the Mississippi River floated around.

According to Big River Magazine, the idea was first studied in 1868, and was considered on-and-off again until Duluth frozen-food mogul Jeno Paulucci made one more push for it in 1967. But a year later, the St.

Continued on page 20

Croix River — usually a key segment in any planned route — was offered protection when it became a National Scenic Riverway.

While some plans called for heading west out of the Duluth-Superior harbor to reach the Mississippi, most would use the St. Croix, which meets the Mississippi in Prescott, Wisconsin.

The Duluth News Tribune in 1912 reported consideration was given to connecting the harbor with the St. Croix via a 36-mile canal through segments of the Amnicon and Moose rivers.

Though it would require building a harbor, another popular route included connecting Lake Superior to the St. Croix via the Brule River. After all, just 2 miles separate the rivers’ headwaters.

But on May 30, 1913, the News Tribune reported the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers determined the project “not feasible” — a conclusion many others would come to during the next 55 years.

Proctor wanted NHL, NFL teams

In the 1920s, Duluth had a team, the Eskimos, in the National Football League. Its storied 1926 season is the basis for the 2008 movie “Leatherheads” starring George Clooney and John Krasinski, and also a book by News Tribune Editorial Page Editor Chuck Frederick.

And in 2015, Proctor City Councilor Travis White wanted some of that professional sports magic back in the Twin Ports.

He first pitched to the City Council, which then passed two resolutions supporting the idea of bringing an NFL team to the region and building an outdoor pro-football stadium.

“It sounds ‘out there,’ but it’s really not out there,” he said at the time.

A couple of months later, White acknowledged many were skeptical of his football idea, and he introduced another resolution urging the area to explore bringing in a National Hockey League expansion team. A new hockey stadium wouldn’t need to be as large as a new football stadium, he said.

He also wanted a minor league baseball team.

Olympic dreams

Besides professional sports, the area has eyed the Olympic Games.

In 1929, civic leaders submitted an application to the International Olympic Committee to host the 1932 Winter Games.

Today, such a bid would be unlikely and require new facilities. But in 1932, there were fewer sports in the Winter Games: hockey, ski jumping, speed skating, figure skating, bobsled, cross-country skiing and Nordic combined. Additionally, curling and dogsledding were demonstration sports.

Duluth leaders said it would be possible to use the “Big Chester” ski jump at Chester Bowl and the Duluth Curling Club’s building on London Road.

The bid was unsuccessful, however, and the games went to Lake Placid, New York.

The area could have also hosted part of the 1996 Summer Games had it been awarded to Minneapolis instead of Atlanta. Lake Superior would have been the sailing venue while the St. Louis River near Carlton would have been the choice for whitewater kayaking.

Instead, those games were held closer to Duluth, Georgia. u

Fields of dreams

By Jon Nowacki jnowacki@duluthnews.comMcGhie Baseball great Joe DiMaggio visited what would eventually become known as Wade Stadium in January 1941, and, according to legend, waded through snow to take a swing at an imaginary pitch before saying, “Baby, batting out a homer in this park will be a good job for the best of ’em.”

That’s just one of countless stories about Twin Ports professional baseball history, one that goes well beyond Wade Stadium and the year 1941, and surprisingly rich for a city located in a northern clime. According to baseball-reference.com, Duluth won the Northwestern League in its inaugural pro season in 1886, going 46-33 in a six-team league featuring teams from Minneapolis to Milwaukee. Local baseball historian Anthony Bush said nicknames “were added retroactively at some point and now they’re like an invasive species, as far as I’m concerned.” The Milwaukee team, certainly, was not your father’s Brewers, or even your grandfather’s Brewers, but one of multiple Milwaukee teams to carry that name. Later there were the Duluth White Sox (1903-16, 1934) and Duluth Dukes (1935-42, 194655) of the Northern League. Across the bridge, at the old Municipal Stadium, adjacent to the WisconsinSuperior campus, you had the Superior Blues (1933–43, 1946–55). Prior to the New Deal-era parks, Duluth had Athletic Park and Superior had Hislop Park. Among the notable incidents at that time included a visit by the larger-than-life Babe Ruth at the height of his career in November 1926 as part of a vaudeville

Athletic Park in West Duluth, former home of the famed Duluth Eskimos football team. Wade Stadium, which hosted its first baseball game July 16, 1941, with the Duluth Dukes taking on their rival, the Superior Blues, appears to still be under construction. Wade Stadium’s original name was the Duluth All-Sports Municipal Stadium and was renamed Wade Municipal Stadium in 1954 to honor former Dukes owner Frank Wade, who died the previous year. Wade Stadium, constructed of bricks from Grand Avenue, is one of the last remaining stadiums from the Works Progress Administration. (L. Perry Gallagher Jr. / University of Minnesota Duluth Kathryn A. Martin Library Archives)

tour, the Bambino posing with orphans at Fairlawn Mansion in Superior in a classic photo.

Tragedy struck on July 24, 1948, when the Dukes were involved in one of the worst tragedies in sports history when they were involved in a bus crash that claimed six lives, including outfielder Gerald “Peanuts” Peterson, of Proctor, and injured more than a dozen more.

Eventually Wade Stadium was home to the Duluth–Superior Dukes of the 1960s, a golden age that saw the likes of four-time Major League AllStar Willie Horton and two-time Cy Young Award winner Denny McLain — the Majors’ last 30-game winner — play for the Dukes as the team was a Detroit Tigers minor-league affiliate.

The big names funneled through the Twin Ports at that time through the Northern League were a “who’s who” of all-time greats, including legendary sluggers such as Hank Aaron and Roger Maris, and ace pitchers Don Larson and Gaylord Perry.

The Northern League disappeared, only to come back in 1993, reborn as an independent league. The Duluth-Superior Dukes were a charter member and played in the Northern League through the 2002 season before moving to Kansas City, where they became the T-Bones.

That stint wasn’t without its share of memories, with titles in 1997 (League) and 2000 (Central), not to mention Ila Borders, who in 1998 became the first female pitcher to start a men’s professional baseball game.

The Dukes were replaced by the Duluth Huskies of the Northwoods League, a collegiate summer

league featuring wood bats that helps players develop and become accustomed to what minorleague baseball would be like. While the league has been a hit, it’s hard to know who’s going to be the next Pete Alonso or Max Scherzer, both league alums.

Of course, nobody watching Hank Aaron at Wade Stadium in the early 1950s knew he was going to be Hank Aaron, either.

Part of what made the revamped Northern League fun was the interesting mix of players it brought together, college players who were passed over in the draft, minor-league retreads, aging or washed up former major leaguers or players with big-league talent who had “issues.”

Count Darryl Strawberry as part of the latter. Strawberry, an eight-time MLB All-Star who struggled with addiction, was playing at Wade Stadium with the St. Paul Saints in 1996. While Strawberry would go on to win a World Series with the New York Yankees that year, at that time, he had to prove, “I still got it.”

Well, he had it, launching one that left no doubt. The line-drive home run cleared the Little League backstop beyond Wade Stadium’s centerfield fence and supposedly left a divot by second base, an estimated distance of 540 feet, but even that is argued and now part of legend. And that’s what makes baseball great.

As longtime Twin Ports baseball fan Jon Winter recalled: “I think that ball is still going.” u

Moonshine poured across Canadian border

By Tom Olsen tolsen@duluthnews.comWhen Prohibition became the law of the land in January 1920, it didn’t take long for liquor to start flowing across the Canadian border into Northeastern Minnesota.

Customs officials were told to keep a close eye on trains, vessels and automobiles entering the United States. Cargo was searched, and boats were stationed on the Great Lakes to watch for suspicious activity. Authorities triumphantly announced the break-up of smuggling rings and the seizure of casks of whisky.

But it rapidly became apparent that federal, state and local authorities were grossly overmatched in their efforts to combat cross-border transportation and backwoods brewing operations that supplied an entire industry of speakeasies across the Northland.

“Smuggling of whisky from Canada into northern Minnesota, its illegal manufacture in the northern wilderness, and its sale in the cities on the range and in Duluth cannot be effectively curtailed at the present time,” the News Tribune reported in November 1920, citing a report from Duluth-based federal prohibition agents.

The paper reported that the “little fellows” — farmers, laborers and owners of soft-drink parlors — were in the majority of those caught in the first year of constitutional Prohibition. The region’s 68-agent force was simply ill-equipped to deal with major rum-runners keeping the revelry alive in the Northland.

“The men who have been manufacturing the stuff that these are selling have seldom been

Duluth Police Chief John Murphy was among a group of men arrested in July 1920 on charges of attempting to smuggle more than 1,200 bottles of liquor from the Canadian border to Duluth for sale.

captured,” the paper reported. “Prohibition agents admitted that on many occasions the moonshiners have seen the agents before the agents ever saw them. This, they say, has been due to the lack of agents. One or two would be assigned to a small town, and within a short time, many in the neighborhood had been informed that ‘the revenue men are in town.’”

Duluth police chief arrested for smuggling

Headlines described daily confiscations of casks hidden within rail shipments and grand jury indictments for men accused of liquor smuggling — some of them rather prominent members of the community, including Duluth’s police chief, John Murphy.

Best remembered for his role in the arrests of several Black men who were lynched by a mob in downtown Duluth, Murphy was arrested just weeks later, along with a deputy U.S. marshal, for allegedly attempting to smuggle 1,236 bottles of liquor from the Pigeon River in Cook County to Duluth for illegal distribution.

Murphy, a former railroad man who had no law

enforcement background when appointed chief in November 1919, also was indicted on a second case that alleged a conspiracy to transport a large quantity of liquor from Fort Frances, Ontario, to Eveleth in freight cars operated by the Duluth, Winnipeg and Pacific Railway, whose employees were also among those charged.

By the time Murphy and several co-defendants

Continued on page 26

Duluth Police Chief John Murphy and two other men were cleared of liquor-smuggling October 1920. Murphy claimed he stumbled upon the whisky in a shack near the Pigeon River during a fishing trip and brought it back to Duluth police headquarters as seized evidence.

were set to go to trial in July 1920 — with a legal defense team including three Iron Range mayors — it had become clear the federal courts were already overwhelmed by the influx of smuggling cases.

“I am worn out after six months of continual trial on these liquor cases,” Judge Page Morris said, announcing a three-month postponement to a stunned audience that had gathered to see the

spectacle inside the Duluth courtroom. “Despite my efforts to the contrary I find myself in an irritable frame of mind. These defendants are men of high standing and I don’t think I should hear this case, feeling as I do now.”

Murphy, when he went to trial in October, would be acquitted after testifying that he stumbled upon the liquor in a remote shack during a fishing

trip and dutifully transported the evidence back to Duluth police headquarters (where dozens of bottles would later go missing from a sealed vault). Despites his efforts, the suspended police chief never achieved reinstatement to his position.

‘Blind pigs’ replace saloons as law struggles to keep up

In the Twin Ports, and around the region, it wasn’t hard to find illegal drinking establishments. Locally, speakeasies were commonly referred to as “blind pigs” and frequently run out of soft-drink parlors.

Arrests and fines of business owners were common, as were citations of patrons accused of the crime of drunkenness. Police touted raids that they hoped would not only eliminate existing liquor from the streets but help deter would-be bootleggers from setting up shop.

“The making of moonshine is going to become an extremely unprofitable business,” Duluth Police Chief Warren E. Pugh predicted after an operation known as the “Sponge Squad” kicked off with the seizure of 500 gallons of mash and moonshine, two huge stills and a wagon-load of accessories worth $15,000.

“A concentrated effort to wipe out the too numerous fountains of illicit whisky will be made by the police department and will continue until every available or known still has been seized and

destroyed.”

But demand for booze

always far exceed enforcement capabilities, largely rendering police raids ineffective — as illustrated by a December 1920 dispatch from the Iron Range: “A few hours after Chief of Police (Edward) Cloutier issued an official statement that Chisholm has been freed of all lawlessness, and that there is no more blind pigging going on, federal agents raided a so-called soft drink place on Lake street and confiscated a quantity of moonshine.” u

Get the best under your feet

At Johnson Carpet One Floor & Home, we know how important it is for you to feel confident in your flooring selection. Therefore, we strive to ensure that the floor we’ve created together is as beautiful as the one in your dreams. If not, we’ll replace it for free. That’s what we call The Beautiful Guarantee®.