2023

Life without Parole and the Right to Redemption

Private Equity’s Impact on Nursing Homes

Citizenship

Traveling Black

THE MAGAZINE OF DREXEL UNIVERSITY

THOMAS R. KLINE SCHOOL OF LAW

Amanda Frost on

Stripping

Jamila Jefferson-Jones on

Chapin Cimino on Adam Smith’s Conception of Justice

Contents

of Departure Not Beyond Redemption: Reimagining Life without Parole Wendy Gibbons 4 Dean’s Welcome Daniel M. Filler 3

Table of

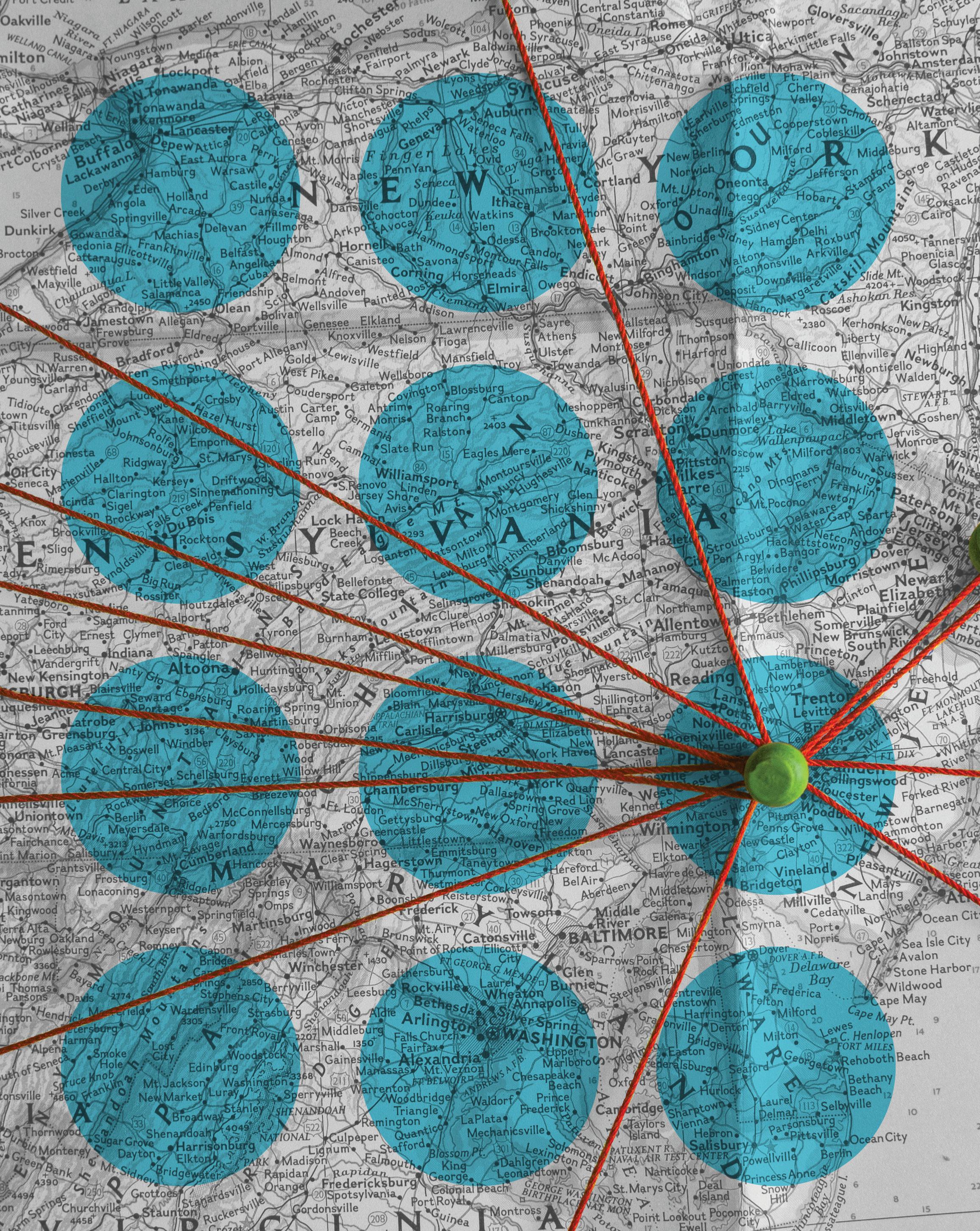

Points

U City Digest News from Drexel Kline Law 42 Scholar-Activist Wendy Greene Charts a New Course at Center for Law, Policy and Social Action 46 Trial Team Racks up the Wins 48 Students Spend Spring Break Helping Immigrants at the U.S.-Mexico Border Inside Back Cover Alumni Make their Marks in the Big Apple Care Inc.: Private Equity’s Impact on the Nursing Home Industry Ben Seal 14 Book Review: Are We There Yet? Jamila Jefferson-Jones 36 Deciding Who’s American: A Q&A with Author Amanda Frost 24 How Do We Know Justice? Adam Smith’s Law Chapin Cimino 32

LEX Photography and Illustrations

LEX: The Magazine of Drexel University Kline School of Law Fall 2023 Dean Daniel M. Filler Managing Editor Nancy J. Waters Creative Director Brian Crooks Art Direction & Design Jan Šabach Code Switch Proofreader Purnell Cropper Type Metric 2, Tiempos Text, Pressio, Martin Printer Brilliant Graphics The Drexel University Kline School of Law publishes LEX once per year. Printed on FSC certified paper. Editorial Offices 3320 Market Street, Philadelphia, PA 19104 Telephone (215) 571-4804 Email lawdean@drexel.edu

3: Zave Smith Photography 4: Adobe Stock/Elephotos 5–6: Purnell Cropper 7: Jeff Fusco 9: Vera Institute 10: Dan Gleiter of Penn Live ©2017 12: Purnell Cropper 14–15: Brian Crooks 16: Jan Šabach 17: Zave Smith/Jan Šabach 18: Jan Šabach 19: Penn Carey Law 20: Rachel Hulin/Jan Šabach 21: Jan Šabach 22: Cornell University School of Industrial and Labor Relations 24–25: Julia Davis 26: Beacon Press 30: Shutterstock 32: Brian Crooks 34–35: Alamy 36–37: NY Public Library Digital Collections/Jan Šabach 38–39: Jan Šabach 39: Harvard University Press 40: Brian Crooks and Jan Šabach 42–43: Zave Smith 44: Purnell Cropper 45: Purnell Cropper 46–47: Boarder Tsai, JD ’24 48–49: Clarissa Boone BC: Brian Crooks/Purnell Cropper

Dean’s Welcome

arack Obama’s slogan “elections have consequences” has been prophetic. In the past two terms, a new Supreme Court majority has begun a long-expected project of reworking constitutional law. The court’s dramatic reimagining of abortion rights and affirmative action has forced individuals and institutions to navigate new constitutional realities. But these decisions are only the beginning—not the end—of the story for both the court and the society that receives them.

Our theme for LEX 2023 is “points of departure.” That phrase conjures both place and time, movements both geographic—trains leaving a station, ships sailing out of a harbor—and chronological—pages flipping on a calendar, eyes fixed on the moving hands of the clock. The articles in this issue tell the stories of individuals and organizations confronting massive change and how they respond to it.

Some of the departures explored in this issue of LEX are quite literal—like Terrell Woolfolk-Carter’s departure last year from a Pennsylvania prison. In this issue’s lead story, Wendy Gibbons delves into the question of life without parole sentencing through the lens of WoolfolkCarter’s experiences. With some help from Drexel Kline Law faculty and students, he received a commutation and was released last year after serving 30 years. And, underscoring that, at Drexel Kline Law, scholarship and social action are mutually reinforcing, my colleague Rachel E. López partnered with Woolfolk-Carter and another former lifer, Kempis “Ghani” Songster, to write an article arguing that life without parole sentences violate a cognizable right to redemption. The article won the coveted Law and Society Association Article Prize in 2022.

Old age, of course, is a time of metaphorical and sometimes literal transitions—at least for those of us lucky to live that long. Whether we thrive in those years often depends on the quality of care we receive. In this issue, we look at the impact of private equity on the nursing home industry. Private equity’s intense focus on profits, Ben Seal reports, may not be the best fit for this care-oriented industry, and elder care advocates and regulators have begun to take notice.

Few transitions could be more significant than the forced loss of citizenship. In her book You Are Not American: Citizenship Stripping from Dred Scott to the Dreamers, Amanda Frost of the University of Virginia

School of Law examines the little-known process of citizenship revocation in the United States through the experiences of a fascinating assortment of people over the course of 175 years. Nancy Waters spoke with Frost about citizenship stripping and what it tells us about who is—and is not—deemed to be an American.

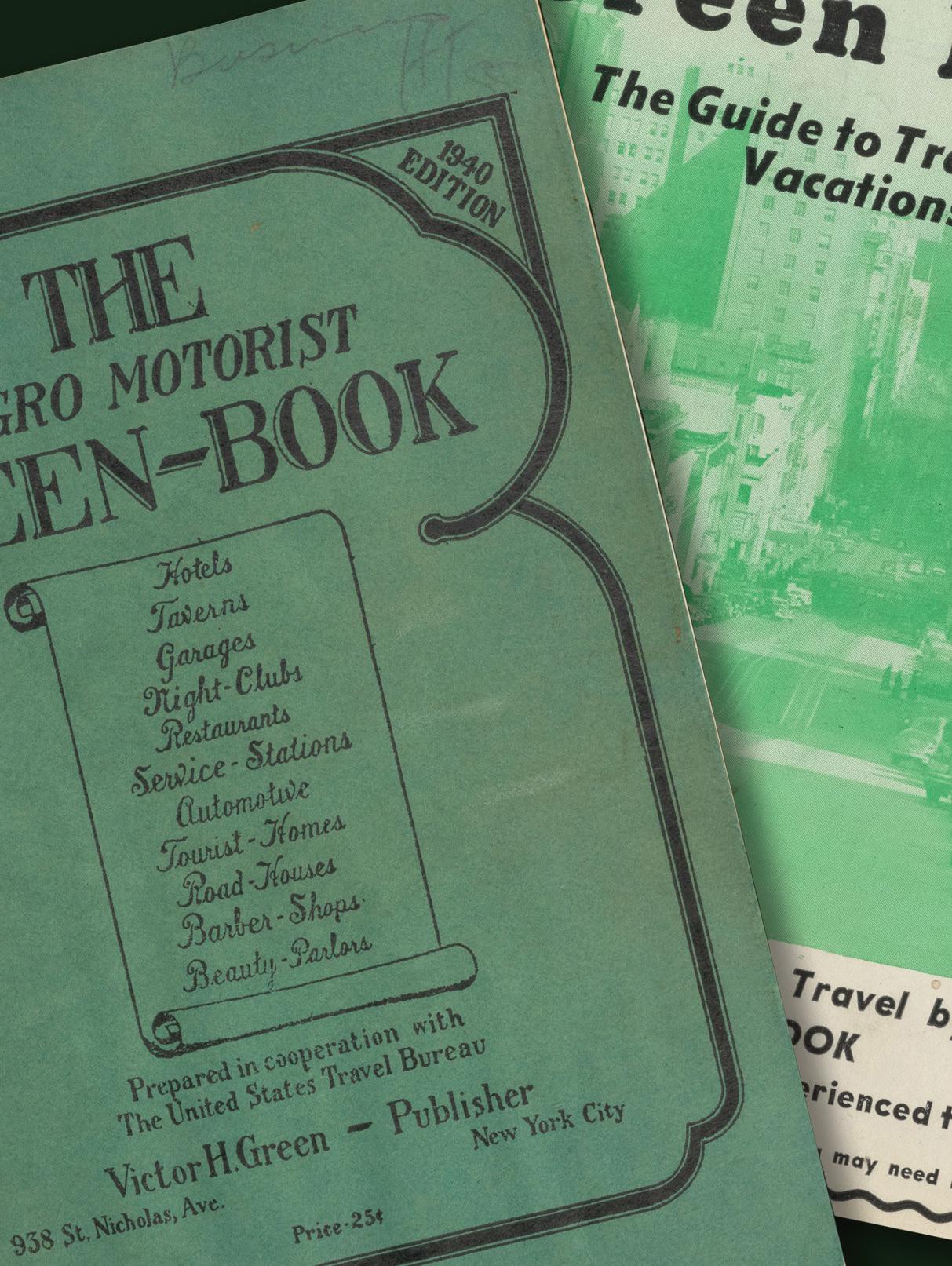

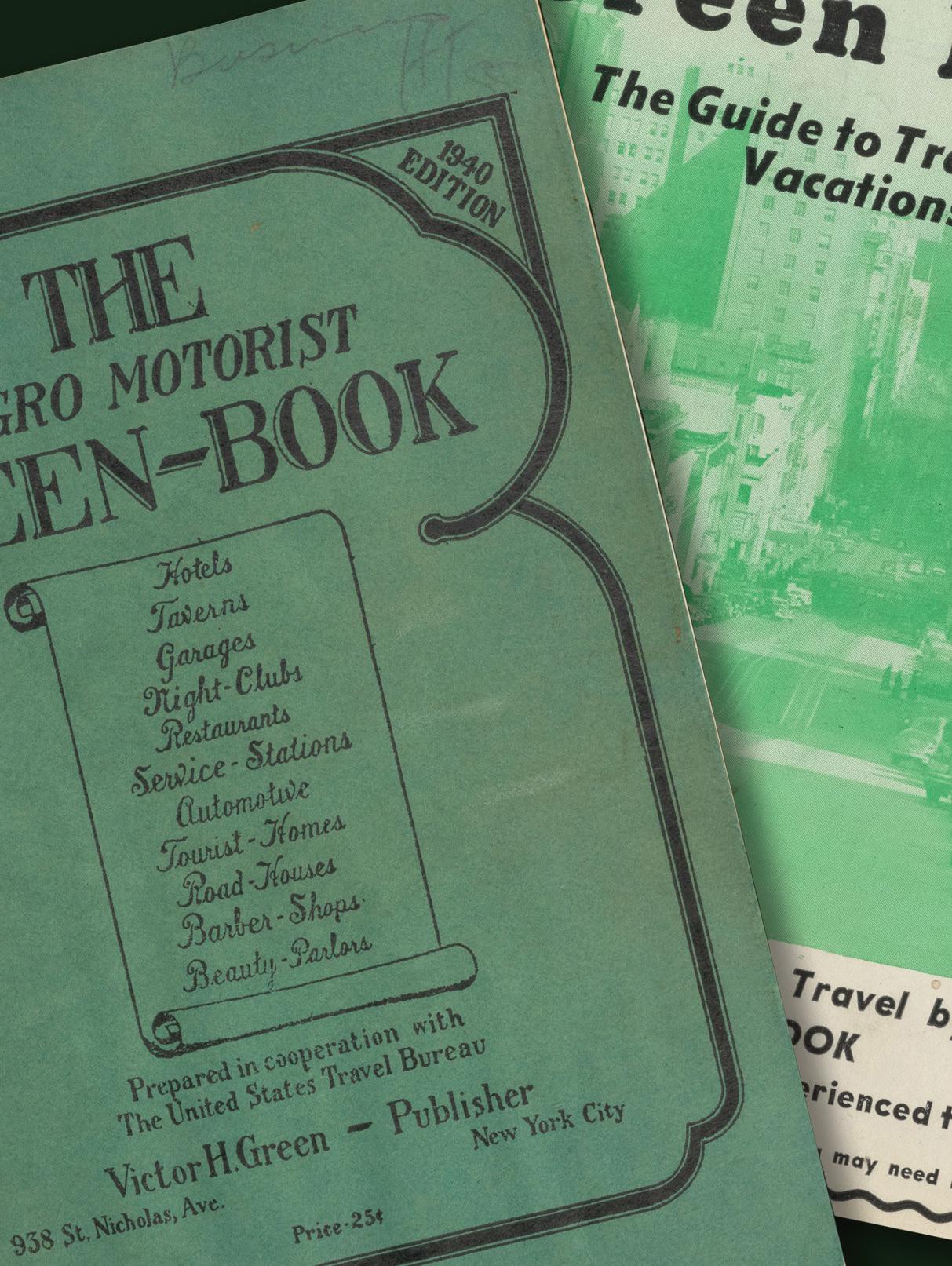

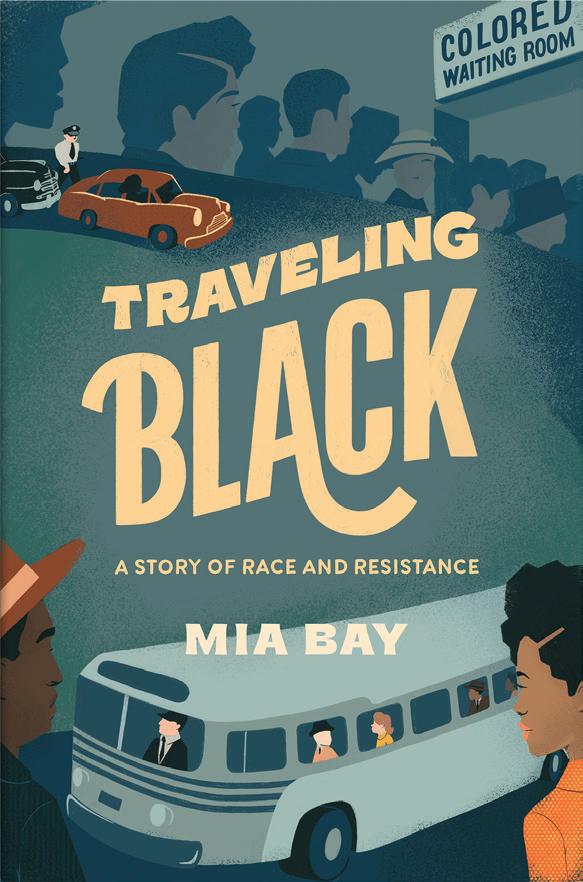

There is no more concrete manifestation of freedom than personal mobility—the freedom to come and go as one pleases. This nation has an ugly history of depriving Black people of their personal mobility, and securing their freedom to roam played a pivotal role in the Civil Rights movement. In these pages, Jamila Jefferson-Jones of the University of Kansas Law School reviews Mia Bay’s award-winning book Traveling Black: A Story of Race and Resistance.

Finally, we conclude our exploration of pivots and progressions with a peek at a long-buried piece of legal history: Adam Smith’s theory of jurisprudence. Drexel Kline Law’s Chapin Cimino tells us that Smith (often caricatured as the ultimate utilitarian) believed that the starting place for identifying just law was listening to one’s intuition. She argues that his sentimentalist philosophy of human nature and the law was groundbreaking in the 18th century and remains an enlightening, and useful, jumping-off point for thinking about just law even today.

When it comes to air travel, experts tell us that the riskiest moments are takeoff and landing. Departures are times of transition, the liminal moments when we leave one steady state in search of another, and takeoffs can be smooth or very bumpy. I believe we are traversing such “points of departure” at this very moment. Where will we land? Like you, I eagerly and anxiously anticipate the answer to that question. And I look forward to hearing your feedback about this sixth issue of LEX.■

Daniel M. Filler

LEX 3

Points of Departure

B

Departures are times of transition, the liminal moments when we leave one steady state in search of another, and takeoffs can be smooth or very bumpy.

REIMAGINING LIFE WITHOUT PAROLE

BY

WENDY GIBBONS

NOT BE YOND RE DEMP TION

In the United States, more than 55,000 people are serving life sentences without the possibility of parole, a fate that some sentencing reform advocates call “death by incarceration.”

Drexel Kline professor Rachel E. López worked alongside recently released lifers Terrell Woolfolk-Carter and Kempis “Ghani”

Songster to write an award-winning law review article arguing that these sentences deprive prisoners of an essential “right to redemption.” They argued that the U.S. should reform outmoded and inhumane sentencing policies, and through their work they also raised a larger question: Whose voices should be included when legal scholars seek to bring the actual practice of the law closer to our ideals of justice?

LEX 5 Points of Departure

When the students in Drexel Kline’s Criminal Law class pay particular attention to frequent guest lecturer Terrell Woolfolk-Carter, it’s not because of his academic degree or the books he has written. Rather, it is because Woolfolk-Carter can bring to life from his own experience a story they might otherwise encounter only in the pages of their textbooks, the story of a man who spent 30 years locked away from his family, friends and community—and who fully expected he would die behind bars.

Woolfolk-Carter, who is now 54, was just 22 years old, younger than some of his students, when he made the horrible misjudgment that shattered his world and ended the life of another. For his involvement in a drug-related robbery and shooting, he was convicted of second-degree murder and sentenced to life in prison without possibility of parole. Following a commutation of his sentence last year, he was released from the Pennsylvania State Correctional Institution (SCI) at Phoenix to a halfway house under the supervision of a parole officer. He now lives with his wife, Stacy Woolfolk-Carter, in West Philadelphia.

“My job is to give [students] a different perception from what is in their books,” Woolfolk-Carter explained over the phone as he walked his dog Smokey down a Philadelphia street one chilly day last winter.

Woolfolk-Carter knows he is lucky to have a second chance. More than 5,000 people are locked away for life in Pennsylvania, and only a few will receive commutations, leaving most to die in prison. The state is one of six in which all life sentences are determinate sentences; in

Woolfolk-Carter knows he is lucky to have a second chance. More than 5,000 people are locked away for life in Pennsylvania, and only a few will receive commutations, leaving most to die in prison.

Terrell Woolfolk-Carter and Kempis “Ghani” Songster celebrate Woolfolk-Carter’s release from prison in July 2022.

other words, parole is not an option. In the United States, more than 55,000 people are serving life sentences without the possibility of parole—and the all-but-certain expectation that they will never again experience life beyond prison walls.

Although the parole process was blocked to him, since 2011 Woolfolk-Carter had been working with other lifers at what was then known as SCI Graterford, the facility that SCI Phoenix later replaced, to expand the possibilities for prisoners serving life without parole (LWOP) sentences to achieve parole eligibility. During a community-based learning workshop inside Graterford in 2014, he met Rachel E. López, an associate professor at Drexel Kline Law and director of the school’s Andy and Gwen Stern Community Lawyering Clinic.

López described meeting Woolfolk-Carter as “deeply inspiring.” He and the other lifers she encountered seemed so “full of wisdom,” she said. It took another eight years, however, for Woolfolk-Carter to persuade the people with the power to grant his freedom that he had earned it. The state Board of Paroles and former Governor Tom Wolf signed off on the commutation of his sentence in July 2022 after Woolfolk-Carter “literally wrote himself out of prison,” López said. His novels, creative writing degree from Villanova University and co-authorship of an award-winning law review article with her and another former prisoner, López explained, helped Woolfolk-Carter make a powerful case for his release.

At Graterford, Woolfolk-Carter and several other lifers had created a group they called the Right To Redemption Committee. López, an expert in international human rights law, discovered that the committee’s conception of a “right to redemption” was aligned with human rights jurisprudence from around the world. Using existing legal doctrine and theory, she helped them articulate the connections between their legal arguments and a 2013 ruling by the European Court on Human Rights. In Vintner v. United Kingdom, the court held that “it would be incompatible with…human dignity…to deprive a person of his freedom forcefully without at least providing him with the chance to regain that freedom one day.” The court concluded that all life sentences should be reviewed regularly to assess whether an individual has made significant progress to rehabilitate themselves, making their continued detention incompatible with justice. Denying them this right amounts to inhuman and degrading treatment, the ruling states.

López strongly believes LWOP sentences in the United States should be abolished. “Sentencing people to life without parole,” she said, is “a violation of human rights because [prisoners] have no understanding of what they need to do in order to be redeemed in the eyes of the state.”

In 2020, during the pandemic lockdown and the nationwide protests over the murder of George Floyd, López enlisted Woolfolk-Carter to join her and Kempis “Ghani” Songster, another man who had already been released from an LWOP sentence at SCI Graterford, to co-author a groundbreaking law review article titled

“Redeeming Justice.” It was published in the Northwestern University Law Review in October 2021 and won the 2022 Law and Society Association Article Prize for the best socio-legal article of the previous two years.

By integrating Woolfolk-Carter’s and Songster’s evocative descriptions of their experiences of imprisonment and redemption with López’s scholarly expertise, they forged a new genre of legal scholarship called “participatory law scholarship.” Together they argue that the United States needs to reform its outmoded and inhumane sentencing policies. They also ask a deeper question: Whose voices should be included when legal scholars seek to bring the actual practice of the law closer to our ideals of justice?

Death by Incarceration

The crux of the argument that López, Woolfolk-Carter and Songster made in their Northwestern University Law Review article is that “all humans should have a legal right to redemption—a right embedded in the Eighth Amendment through the latent concept of human dignity.” Thus, the article calls for “a dramatic re-imagination of the U.S. criminal legal system into one that elevates humanity” and “creates the opportunity for healing and human development.”

Drexel Kline Law professor Rachel E. López joined Terrell Woolfolk-Carter and Kempis Songster to co-author an award-winning law review article contending that all humans have a legal right to redemption.

Drexel Kline Law professor Rachel E. López joined Terrell Woolfolk-Carter and Kempis Songster to co-author an award-winning law review article contending that all humans have a legal right to redemption.

Like anyone facing an extreme threat to his psychological survival, during his incarceration Woolfolk-Carter believed he had to make a choice: He could give up on himself, or he could admit that he had made a terrible mistake and seek atonement. He chose the latter. From within prison, he enrolled in a bachelor’s degree program at Villanova University and joined the hospice team to help care for dying prisoners. He also wrote and published several books under the name Terrell Carter, which, because of a bureaucratic error, was the name he went by in prison.

“I made it through because I had to,” he said. The alternatives, he added, were insanity or suicide.

As decades passed, however, he became disheartened that all of his work to hold himself accountable went unacknowledged, and that he would never have the opportunity to use his experiences to help others outside of prison avoid a similar fate.

“We saw how we became the ‘other,’ not belonging to the human family,” Woolfolk-Carter and Songster wrote in “Redeeming Justice.” “Chaining and shackling people to the worst moments of their lives,” they continued, strips them of their humanity forever and dooms them to leave prison only by way of a body bag. In this way, the authors argued, life without parole constitutes a de facto death penalty, or what has become known in the sentencing reform movement as “death by incarceration.”

Tough on Crime Narratives

In the United States, the imposition of draconian punishments, including life sentences, is a practice that dates to the colonial era. By the late 19th and early 20th centuries, however, reformers sought to balance retributive sentences with parole, from the French term for “giving your word.” Parole boards in each state and in the federal system have the authority to release from prison those prisoners who have shown during incarceration that they have become accountable for their actions and pose little or no threat of committing future harm. All states except Alaska had life sentences on their books during most of the 20th century, but according to a 2013 report by The Sentencing Project, a research and advocacy organization based in Washington, D.C., in practice, “life” typically meant a sentence of 10 to 20 years followed by parole board review, even in the federal system.

Following a notable rise in the crime rate that began after World War II and peaked around 1991, legislatures began to mandate harsher sentencing, and judges and juries responded in kind. Such sentencing reforms as mandatory minimums and “habitual offender” laws were central features of the “tough on crime” movement of the 1980s and 1990s and significantly increased the nation’s prison population. Life without parole sentencing has also clearly contributed to this growth: Since 1984, the number of people serving life sentences in the United States has more than quadrupled, and almost a third of them have no possibility of parole. (Alaska is currently the only state whose sentencing provisions do not include LWOP.)

The LWOP burden falls heaviest on Black men. In Pennsylvania, for example, nearly 70 percent of the prisoners serving life without parole are Black in a state where Black residents make up just 12 percent of the population, according to The Marshall Project, a nonprofit news organization that covers the American criminal justice system. And, at the federal level, racial disparities in sentencing are quite clear. In a report titled “Demographic Differences in Sentencing” published in 2017, the U.S. Federal Sentencing Commission found that in the federal court system from 2005 to 2017, “Black male offenders continued to receive longer sentences…than similarly situated white male offenders.”

In the eyes of reformers, an even more objectionable policy is mandatory life without parole, which offers prosecutors and judges no discretion in sentencing. Pennsylvania is one of at least 17 states in which LWOP sentences are mandatory for certain types of crime. In some states, repeat offender laws such as “three strikes and you’re out” mandate LWOP sentences even for such minor, non-violent offenses as shoplifting if the person has previous felony convictions on their record.

Perhaps ironically, LWOP sentences have been advocated by some who see them as a more humane and certainly more revocable option than the death penalty. Having LWOP sentences available as an option for judges and juries, according to this thinking, may have made it easier to convince some state legislators to eliminate the death penalty because this was an acceptable alternative in the most serious cases. And there is clearly an inverse correlation between LWOP and capital punishment. According to a 2013 report from The Sentencing Project,

8 Not Beyond Redemption

Countries such as Portugal, Brazil and Croatia have banned life sentences of any kind, seeing them as not only unjust, but also ineffective at their stated goals of deterrence and restitution.

“The notion of a whole-life sentence gained popularity starting with the ban on the death penalty, which was in place from 1972 to 1976. Before the U.S. Supreme Court’s decision striking down the death penalty in Furman v. Georgia, only seven states had life without parole statutes.”

In 2022, the Stern Community Lawyering Clinic joined a coalition of civil rights groups to file a complaint with the United Nations Special Rapporteurs requesting an investigation of the United States for serious human rights violations and urging the abolishment of all “death by incarceration” sentences. The Right to Redemption Committee, including Woolfolk-Carter and Songster, also signed the complaint.

The assertion that the United States is the land of “liberty and justice for all” is farcical in the face of its actions, the complaint argues. For example, in 1976, the U.S. signed the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, which states that the essential aim of a penitentiary system should be justice in the form of “reformation and social rehabilitation.” Life without parole would seem to be a practice antithetical to achieving such a goal. Countries such as Portugal, Brazil and Croatia have banned life sentences of any kind, seeing them as not only unjust, but also ineffective at their stated goals of deterrence and restitution. Even life sentences that allow parole are considered inhumane by many countries, whose longest prison sentences are generally limited to 25 to 30 years.

“The United States is an outlier in international jurisprudence,” López explained. To better align the country with global legal standards, the co-authors argue that, at the bare minimum, the U.S. should ban life without parole sentences.

Safety First

Marta Nelson is director of government strategy with the Vera Institute of Justice in New York, an advocacy organization working to end mass incarceration. Advocates of sentencing reform must, she said, address the issue of public safety head on, lest they “run into the buzz saw of the tough-on-crime narrative.” Although it is violent crime that understandably generates the most emotional responses from the public, Nelson pointed out that research shows that recidivism rates for violent crimes like rape, assault and murder are far lower than for nonviolent ones. Studies have found that one to five percent of people passing through the justice system “specialize” in violence and commit from 50 to 75 percent of these offenses. But most defendants, Nelson said, are people who felt “compelled by moments of conflict,” and these individuals are less likely to reoffend.

Research has also shown that young people are far more likely to engage in criminal behavior, but as they age, they also “age out” of crime. A person is most likely to get arrested for a violent crime from ages 18 to 20, but the rate

of arrest is 65 percent lower for people in their mid-30s. In addition, studies show that keeping people in prison into their 40s and 50s needlessly exposes them to “criminogenic” conditions that can increase the likelihood they will engage in harmful behaviors again, Nelson explained. Indeed, a 2013 meta-analysis conducted by Daniel S. Nagin published in Crime and Justice found that people are deterred from unlawful behavior not by the severity of the punishment, but rather by the likelihood of getting caught. Incarceration rates alone appear to have little effect on crime—homicide rates have been falling in Europe, Canada, Australia and the United States, despite the vastly differing incarceration rates in these places, Nelson said.

A focus on retribution, Nelson argued, short-circuits the cause of justice. A more just and effective system, she suggested, would say “OK, this thing has happened, so now what is the most positive outcome that one can have going forward?”

Keeping as many people as possible at home while they work to repair the harm they have caused would “build safety and keep communities stronger,” she continued, by allowing them to continue to raise their children, provide for their families and participate in their communities. “We just assume,” she said, “that a lengthy sentence is what is needed for safety, when the evidence often says just the opposite.”

LEX 9 Points of Departure

Marta Nelson is the director of government strategy at the Vera Institute of Justice in New York.

It may seem counterintuitive, but Nelson also argued that a system focused more on restoration and less on retribution would better address the harms caused to victims. Crime survivors typically report that they do not view harsh sentences as sufficient outcomes. “If you talk to crime survivors,” she said, “they want much, much more.”

Participation in restorative justice programs, on the other hand, has been shown to decrease rates of reoffending, as well as better promote the healing of victims.

Nelson and her coauthors advocate for capping prison sentences at 20 years for adults and 15 years for anyone under the age of 25. Rare cases in which an individual poses a long-term safety threat could be reviewed by an expert review board, and the person further incapacitated through civil commitment. By prioritizing liberty, safety and repair, states would better follow the American Law Institute’s Model Penal Code. Over the past two decades, U.S. Supreme Court decisions have reduced some of the harsher sentences for drug offenses and for juveniles, but these, Nelson said, amount to “tinkering around the edges.”

The Commutation Bottleneck

Indeed, the imposition of less harsh sentences has begun to reduce prison populations, but at the current rate of decarceration, it would take until 2091 to cut the prison population in half in the U.S., according to a 2019 report by The Sentencing Project. According to a 2022 investigation by The Marshall Project, the hundreds of thousands of people currently serving long prison terms will experience little impact from new statutes that don’t apply retroactively, and even novel laws that allow for

Not Beyond Redemption

prosecutor-initiated review and resentencing of old cases in Louisiana, California, Washington, Georgia and Maryland are likely to have limited impacts. District attorneys, the Marshall Project report states, are disincentivized to revisit old cases because they will incur hefty expenses in the process, but the savings from reduced incarceration aren’t likely to be passed along to them.

In Pennsylvania, the process for receiving a commutation is lengthy and complex. First, prisoners must apply by listing all of their convictions and stating what happened and how they were involved. The form includes an optional personal statement about how an individual’s life has changed and why they feel they would be a good candidate for clemency. Following submission of the application, it can take as long as two years for the Board of Pardons to consider it and decide whether to allow a merit review hearing.

10

The Pennsylvania State Correctional Institution at Graterford (shown here), where Terrell Woolfolk-Carter served most of his sentence, was replaced in 2018 with a new facility, SCI-Phoenix. The prison is about 30 miles northwest of Philadelphia.

Kris Henderson is the Executive Director of the Amistad Law Project, a Philadelphia-based legal resource center that served as co-counsel alongside the students from Drexel Kline Law’s Stern Clinic who represented Terrell Woolfolk-Carter in his effort to secure a commutation. Amistad helps individuals with their merit hearings. Over the past five years, 11 of their clients’ petitions have been successful, Henderson said. Preparing clients for interviews with the Board of Pardons is a key part of the process.

We try to “rattle them a little,” they said, “because we know it is really intense.” Commutation hearings can be so traumatizing for prisoners that some refuse to reapply even though it can take three to five hearings to secure their release, they continued.

Ending “death by incarceration” is one of Amistad’s policy goals. Among other initiatives, the organization engages district attorneys, including Philadelphia’s Larry Krasner, to advocate for less harsh sentencing. Because of the large number of people serving LWOP in Pennsylvania and the lengthy, capricious nature of the commutation process, the only meaningful chance for most individuals would consist in legislative action such as SB 835 sponsored by State Senator Sharif Street, which would allow ill or aging incarcerated people to petition the parole board for compassionate release, Henderson said.

Knowing him so well “made us better lawyers for him.”

Redemption, Rehabilitation and Restoration

David R. Dow is the Cullen Professor of Law at the University of Houston and a founder of the Texas Innocence Project. Dow has been speaking out against LWOP sentences and advocating for recognition of prisoner redemption for over a decade. “Sending a prisoner to die behind bars with no hope of release is a sentence that denies the possibility of redemption every bit as much as strapping a murderer to the gurney and filling him with poison,” Dow wrote in a 2012 article for The Nation

Dow sees investments in young people and their communities as essential for breaking the cycle of family trauma that results in mass incarceration. In addition, he advocates that juvenile records be sealed in those states that do not already do so, which would make it easier for young people who have committed crimes to join the military, find jobs and receive financial aid for college. Developing integrated programs to guide young people through complex juvenile justice and family court systems and cope with school disciplinary procedures would help communities heal from decades of social injustice, he added.

Kempis “Ghani” Songster won release from prison in December 2017 following the 2012 U.S. Supreme Court’s decision in Miller v. Alabama, which held that imposing mandatory LWOP sentences on people under the age of majority (also known as children) violates the Eighth Amendment prohibition of cruel and unusual punishment. He now directs Healing Futures, a restorative justice diversion program within the Philadelphia-based Youth Art and Self-empowerment Project, an independent youth-led organization focused on keeping young people out of adult prisons.

When the district attorney’s office sends a young person to him, he uses neutral terms such as “responsible youth” and “person harmed” to avoid stigmatizing young people with coded retributive language. He and his team help both parties develop a plan for restoration, which must be carefully supervised and monitored. “This is not a soft process,” Songster said. Young people find the work they must do to repair the harms they have committed both intense and rewarding, he added.

12

Redemption

Not Beyond

Terrell Woolfolk-Carter gets a hug from his daughter following his release from prison last year.

Restorative justice programs promote accountability by framing crime less as a violation of rules and more as an injury to people’s relationships. People can best redeem themselves and promote healing by seeking to repair this harm. “You are in debt to a person,” not just to society, Songster explained.

Democratizing Legal Scholarship

Woolfolk-Carter and Songster believe that their stories illustrate how redemption can occur behind prison walls and that sentencing practices should reflect this reality. By formally including the testimony of those who have experienced the nation’s justice system firsthand as a new genre of legal scholarship, López aims to expand and reframe the intellectual dialogue around crime and punishment in the United States. The goal, Woolfolk-Carter, López and Songster write in “Redeeming Justice,” is to “infuse the criminal justice system with complexity and hold space for individual circumstances.”

López recently penned a follow-up article that will be published in the Columbia Law Review advocating the creation of an even broader movement, asking, “How do we construct knowledge—collaboratively or as individuals?”

“We’re calling it participatory law scholarship, which is legal scholarship written in collaboration with those that have no formal legal training, but expertise in laws’ injustice through lived experience,” López explained. In February, she helped organize participatory law workshops at Drexel Kline Law and at Northwestern University’s Pritzker School of Law.

“I think it’s fantastic,” Dow said, about the idea of participatory law, adding, “I have learned a lot from these people who occupy a different world than me.”

Exposing law students—as well as their professors— to diverse voices represents another way to democratize the practice of law, López said. Focusing too tightly on training lawyers to become experts in legal technicalities can contribute to a psychological distancing between them and their clients that may weaken trust, preventing lawyers from finding meaning in their work and hampering effective representation. Knowing Woolfolk-Carter so well “made us better lawyers for him,” she said.

By leading discussions with students in López’s Criminal Law class, Woolfolk-Carter, who grew up in the

Mantua neighborhood that borders Drexel University, hopes to bridge the gap between academic institutions and the larger communities that surround them. To help them understand how the “presumption of innocence and reasonable doubt,” play out in real life, he shares stories about living in the city as a young Black man. “We don’t have the presumption of innocence,” he said, because society “literally paints the face of criminality black.”

“The law,” he continued, “is only as good as the people who carry it out.” Woolfolk-Carter wants students to see things more holistically, so that, in the fog of trial, with both sides fighting for a win, they will remember that defendants “are people whose humanity must be recognized.”

Julianna Kearney, JD ’25, who was a first-year student in López’s Crim Law section this past year, called Woolfolk-Carter’s story “incredibly eye-opening.” Law students’ intense focus on learning the minutiae needed to pass the bar exam can lead to an insulated academic experience, she said, but hearing Woolfolk-Carter’s story, on the other hand, “is going to make me a better lawyer and a better person.”

Both Woolfolk-Carter and Songster share a vision: that the criminal justice system will make space for the possibility of redemption. Rehabilitation processes, Woolfolk-Carter argued, are engineered by the state. “Rehabilitation,” he said, “is something the state does to someone.” Redemption, on the other hand, is a selfdriven process. “Redemption is something a person does for themselves,” he said.

Terrell Woolfolk-Carter’s work to redeem and repair continues. He is assisting other Pennsylvania prisoners with their commutations by working with the Stern Clinic to write a guide for current petitioners. People seeking commutation, he explained, must convince the Board of Pardons that the “impulsive, irresponsible or inconsiderate selfish space you came from has become an unselfish one.”

Woolfolk-Carter’s memories of working on the prison hospice team and holding the hands of his dying mentors continue to motivate him. No one, he said, wants “to pass away surrounded by people who don’t care if you live or die.” Society must, he continued, allow those serving life sentences to “exercise our right to be human.” ■

13 Points of Departure

Both men share a vision: that the criminal justice system will make space for the possibility of redemption.

Wendy Gibbons is a science educator, freelance writer and avid birder.

CARE INC.

Private Equity’s Impact on the Nursing Home Industry

As COVID -19 tore through the United States in March 2020, nursing homes rapidly emerged as ground zero in the pandemic. Inhabited by vulnerable elderly and disabled residents, and staffed by overworked caregivers, American nursing homes became their own makeshift triage centers. Visitors were turned away. Family members, fearing the worst, kept calling, desperate for good news. In many cases, staff were too overwhelmed by outbreaks to even answer the phone.

ByBenSeal

14 Care Inc.

LEX 15 Points of Departure

Few facilities escaped the first phase of the pandemic unscathed, but there was one subset of nursing homes where the virus spread with even greater ferocity— and where the death toll was even higher. Private equity-owned facilities, where staffing levels are often minimized to maximize profits, suffered an outsized scale of infection and death. According to a study by the Americans for Financial Reform Education Fund (AFREF), in New Jersey during the pandemic’s first five months the infection rate at nursing homes with private equity owners exceeded the statewide nursing home average by 25 percent and the average rate at the state’s public facilities by 57 percent. And the same study reported that the fatality rate in the state’s private equity-owned nursing homes exceeded the statewide nursing home average by 10 percent.

That a novel respiratory virus that poses the greatest risk to the elderly would wreak havoc in care facilities was, in retrospect, predictable. But whatever was going so wrong in private equity nursing homes was invisible beyond their walls. “Families weren’t allowed in, so people had very little idea what was actually going on,” said Toby Edelman, senior policy attorney at the Center for Medicare Advocacy. “Looking in a window was hardly an answer.”

The alarming scope of the damage that Covid inflicted on residents of nursing homes owned by private equity firms comes as no surprise to those familiar with the broader history of insufficient staffing, inadequate care and increased mortality at these facilities—a track record that has raised concerns among legislators, regulators and policy advocates. As private equity firms expanded their control in the nursing home industry, they crafted corporate structures that have enabled them to reap profits while often avoiding accountability for the disproportionate levels of healthcode violations and death at their skilled nursing facilities.

Private equity firms typically work by pooling investments from a limited group of partners into a fund to purchase a stake in a private company with growth potential, then sell that stake years later and disburse the profits to the fund’s partners. This structure has been around for decades, but it didn’t take off until the 1980s and has exploded this century; thousands of American private equity firms now hold roughly $6 trillion in combined assets under management. As their reach has expanded, their critics charge, so have the problems they have caused. According to a report from the Center for Popular Democracy and the Private Equity Stakeholder Project, private equity firms have been directly or indirectly responsible for 1.3 million lost jobs in retail and related industries in the last decade, while a study from the AFREF blamed private equity for more than half of bankruptcies since 2015. Critics have also assailed them for increasing tuition and student debt in higher education, and for unaffordable rents and higher eviction rates in the housing market.

In health care, private equity’s stake has grown twentyfold over the past 20 years, and, according to a June 2021 study from the Medicare Payment Advisory Commission,

16 Care Inc.

these firms now own 11 percent of nursing homes in the United States. Meanwhile, baby boomers are reaching the age at which they will begin to need these services and the proportion of elders in the population is ballooning: The nursing home industry overall is expected to grow to $240 billion by 2025.

Some studies suggest that private equity’s participation in this sector has come at the expense of resident safety. A study published by the National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER) and led by Atul Gupta, an assistant professor of health care management at the Wharton School, reported that private equity ownership increases the short-term mortality of Medicare patients by 10 percent, accounting for nearly 2,000 unnecessary deaths each year.

Private equity’s business model is built on the expectation of a significant return on investment over a short time frame. This model “is the exact opposite of what a primary goal should be in health care, which is to serve patients and deliver quality care,” said David R. Hoffman, a practice professor of law at Drexel Kline whose consulting firm is a state and federal monitor for long-term care facilities. “Entities are entitled to a reasonable profit, but not at the sake of endangering patients.”

The Private Equity Playbook

Between 2000 and 2018, private equity’s stake in the health care industry overall grew from $5 billion to $100 billion. Its focus on nursing homes also grew in that time, spurred by the enormous potential of an industry in which 70 percent of facilities are run as for-profits and 75 percent of the revenue comes from Medicare and Medicaid.

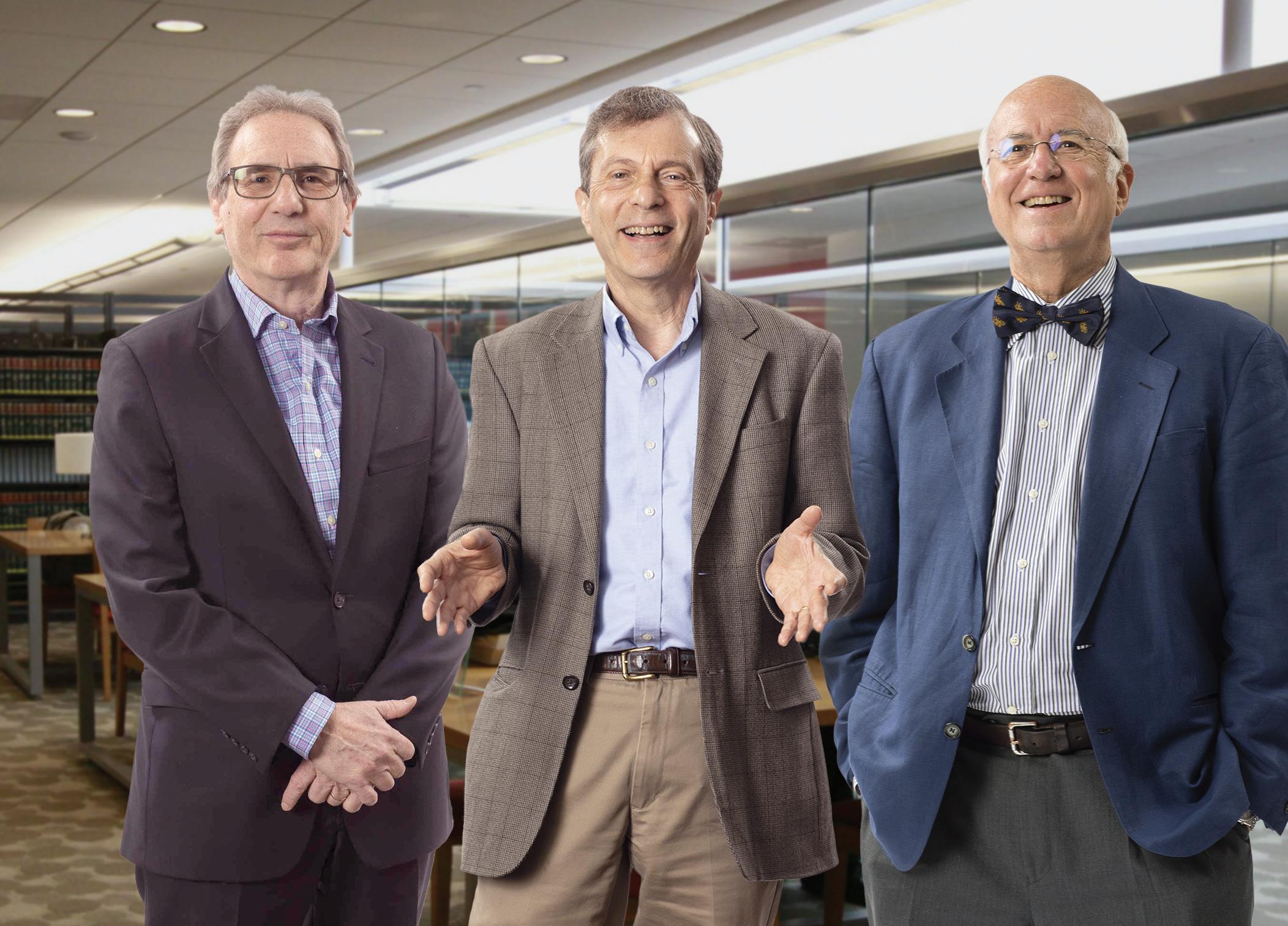

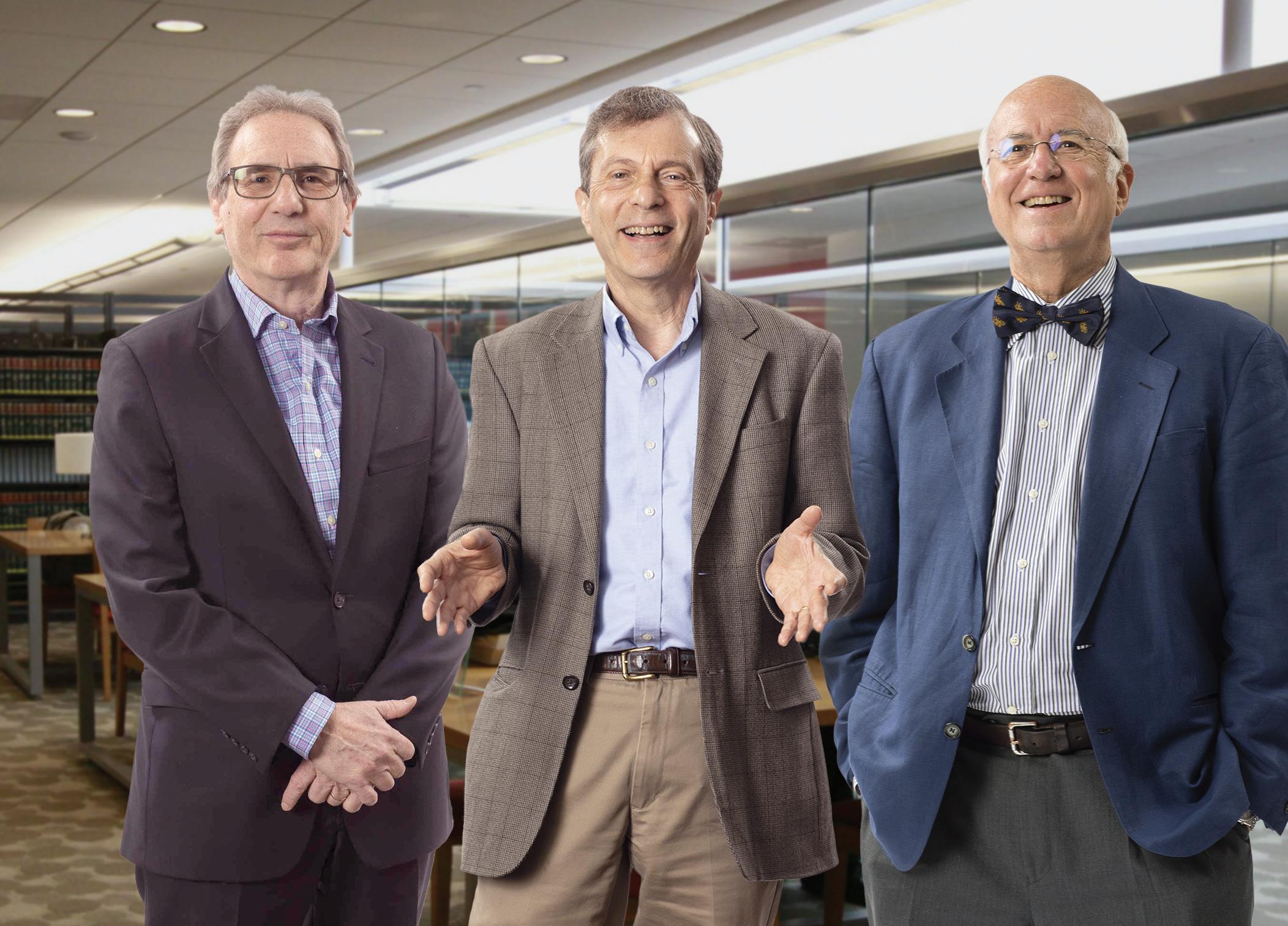

Robert I. Field, a Drexel Kline Law professor and director of the university’s JD and Master of Public Health (MPH) dual-degree program, has studied the relationship between the public and private sectors in health care and how government policies impact the care provided in private facilities. In nursing homes, he said, the relationship is becoming increasingly dysfunctional.

“Private equity is taking that partnership to an extreme,” Field said. “It’s no longer a collaboration in the interests of better health care. It’s becoming a raw profit-making opportunity.”

In Pennsylvania, for example, Medicaid reimburses nursing homes $235 per resident per day, generating a reliable stream of revenue that makes it easy to manipulate costs to maximize profits.

“What could be better if you’re running a business than a guaranteed customer base backed up by a large federal insurance pool?” asked Barry R. Furrow, a Drexel Kline professor and director of the school’s health law program.

LEX 17 Points of Departure

As private equity firms expanded their control in the nursing home industry, they crafted corporate structures that have enabled them to reap profits while often avoiding accountability for the disproportionate levels of health-code violations and death at their skilled nursing facilities.

Drexel Kline Law professors David R. Hoffman, Robert I. Field and Barry R. Furrow have studied the impact of private equity ownership on nursing home care.

With such a secure source of revenue available, private equity firms operating nursing homes follow what has become a well-established playbook to send as much money as possible to the bottom line, legal scholars and long-term care experts say. Rather than acquiring a business, maximizing efficiency and flipping it for a profit— as they might do in another industry, such as retail, for example—these firms instead use complex corporate arrangements to impose excessive fees on the facilities they acquire and turn their real estate into an asset that can survive a potential bankruptcy.

Their first step after purchasing a facility or chain is to create a series of limited liability companies to separate the property, assets and operations. Putting the property in the hands of a tax-advantaged real estate investment trust (REIT), for example, allows a private equity firm to use a “sale-leaseback” agreement to charge nursing homes escalating rent, in addition to maintenance costs, insurance and taxes. Shielded by layers of corporate armor, private equity can effectively function as a well-protected landlord, reaping the significant rewards of property ownership from a captive tenant, while avoiding any consequences from litigation, regulatory scrutiny or even bankruptcy.

The second move in the playbook is the establishment of a series of related companies, all owned by the same private equity firm, but each offering a different product or service—payroll processing, food services, linens, pharmacy, facility management or medical devices, for example—that can be sold to a nursing home and its residents at excessive prices. In some cases, the result is a collection of hundreds of companies across a nursing home chain, all feeding back to the same private equity firm. This structure makes it all the more challenging for prosecutors, regulators and residents’ families to hold private equity accountable for the most damaging impact of its operation of a nursing home: the reduced staffing that can result in patient harm.

The NBER study found that private equity ownership leads to a 3 percent decline in hours per patient-day provided by nursing assistants who serve as the primary caregivers in nursing homes and whose employment represents their largest cost. Overall staffing declines by 1.4 percent. Coupled with a 50 percent increase in the use of antipsychotic medication—dangerous in elderly patients but one way of coping with insufficient staffing—the

18 Care Inc.

What could be better if you’re running a business than a guaranteed customer base backed up by a large federal insurance pool?

result is a level of care that falls short of regulators’ expectations and can be life-threatening. In the New Jersey study, private equity-owned facilities provided residents with 20 percent fewer nursing hours than public and nonprofit facilities, and they were cited for deficiency violations 50 percent more often.

Pam Walz is a supervising attorney in the health and independence unit at Philadelphia’s Community Legal Services. “Anything that affects staff affects residents,” she said. “Staffing levels are key to quality of care.”

Walz has partnered with the Service Employees International Union (SEIU), which represents nursing home workers in Pennsylvania. She has found that nursing aides regularly lament the challenges of working with insufficient staff, “how exhausting it is, how demoralizing it is and how dangerous it is, because injuries happen when you don’t have enough people,” she said.

In other industries, private equity can find efficiencies to exploit. But there are no cost-effective methods for improving the welfare of nursing home residents, Furrow argued. Taking care of the elderly and disabled unavoidably requires lots of care and lots of attention.

“The irony of it is they’re sitting on lots of money they could invest in nursing homes, but that’s not their model,” he continued.

Instead, private equity firms—and, increasingly, other for-profit chains—apply an approach that can be particularly harmful given the realities of the industry and the needs of the people it exists to serve.

The Impact of Insufficient Oversight and Regulation

Agrowing group of individuals, agencies and institutions are struggling to protect nursing home residents by bringing private equity-owned and other for-profit nursing homes into compliance. Their most significant challenge is the lack of transparency in the ownership and operation of these entities. It is typically unclear when a purchaser is backed by private equity, let alone how the tangled web of related parties is woven and who is truly responsible when something goes wrong.

“Regulators have just started to pay attention to and track these transactions, so that is positive, because it’s

the first step to being able to regulate them,” said Allison Hoffman, a deputy dean at the University of Pennsylvania Carey Law School and an expert on health care law and policy. “But it could be too little, too late.”

For residents, the workers charged with their care and residents’ families, a sale—to private equity or otherwise—can be distressing. In the case of a private equity purchase, in particular, it is often all but impossible to determine who is actually in charge.

“The problem,” explained Walz, “is that a sale happens behind closed doors. Nobody tells residents or families or staff. The first time anybody knows about it is when the name changes on the door or, for residents, when the uniforms change.”

Lacking the resources to adequately review a sale— and, often, without the regulatory structure that would require a comprehensive review—states struggle to fulfill their watchdog role, Toby Edelman said. In some cases, this lack of effective oversight allows individuals with a checkered history at previous facilities to acquire new ones.

“The states just let them do what they want,” she said. “It’s terrifying and getting worse.”

Litigation under the Federal False Claims Act, which was designed to prevent contractors from defrauding the government, and monitoring under the 1987 Nursing Home Reform Act, which established basic rights and services for residents of nursing homes, have both failed to prevent the harm caused by insufficient staffing and

LEX 19 Points of Departure

Allison Hoffman of the University of Pennyslvania Carey Law School is an expert on health care law, including elder care policies and Medicare.

substandard care, lawyers and advocates say. Settlements are typically paid by nursing home operators, rather than the private equity firms that own them, and corporate integrity agreements are toothless.

“Most of the time the settlements are pathetic. These companies have stolen millions and millions of dollars [from Medicare and Medicaid] and they’re settling for a fraction of that,” said Charlene Harrington, professor emerita of sociology and nursing at the University of California San Francisco (UCSF). “And then they put in a monitor and basically nothing happens.”

What’s worse, Edelman said, is that the public remains in the dark once a corporate integrity agreement is announced, muting its impact. Medicare offers consumers the Care Compare web site, she explained, but that site provides no information to the public that a nursing home is part of a chain that’s included in a corporate integrity agreement.

“People have no knowledge of that,” she continued. “The corporate integrity agreement becomes a slap on the wrist because it’s all secret and nothing really changes to improve care for residents.”

Enforcement is made all the more challenging, of course, when the most powerful tool in the arsenal—closing a facility—will have the most punishing impact on residents and their families, said Field. “Enforcers’ hands are tied,” he explained. “You don’t want to resort to the nuclear option.”

Authorities Take Notice

In the wake of mounting research and reporting on private equity’s perilous push into long-term care, state and federal authorities are beginning to take notice.

“As Wall Street firms take over more nursing homes, quality in those homes has gone down and costs have gone up,” President Joe Biden said in his 2022 State of the Union address. “That ends on my watch.”

In February, on the heels of a report from the Government Accountability Office urging improved transparency, the Biden administration proposed a rule that would require nursing homes to provide additional information to the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) about their ownership and management. It would also force facilities to clarify whether their owners

20 Care Inc.

Toby Edelman is senior policy attorney at the Center for Medicare Advocacy. She has been representing older people in long-term care facilities since 1977.

are private equity investors or real estate investment trusts.

Although they acknowledge the Biden administration’s commitment to the issue, some experts nonetheless question whether the regulations will generate sufficient information to provide a clear picture of the finances and ownership activity at private equity-owned nursing homes. Harrington argues that CMS should require private equity-run facilities to file consolidated cost reports, like those provided to the Securities and Exchange Commission by publicly traded nursing homes, to provide a complete view of how their money is spent.

At the state level, new regulations in Pennsylvania will require public notice of ownership changes at nursing homes and will raise the minimum staffing level— although because of industry pushback, the increase is only 70 percent of what the state’s Department of Health requested. New York and New Jersey, meanwhile, have recently passed legislation establishing a ratio of revenue that must be spent directly on resident care—90 percent in New Jersey and 70 percent in New York, which also capped nursing home profits at 5 percent. An industry lawsuit fighting the New York law claimed the state would have clawed back $824 million in profits if the law had been in effect in 2019.

More states are also seeking to better apply their certificate-of-need laws, which require regulatory approval for the establishment or expansion of health care facilities, to oversee private equity’s role in the nursing home industry, Allison Hoffman said.

Advocates and legal scholars point to two recent state-level prosecutions as models for effective enforcement. In New York, Attorney General Letitia James sued three separate nursing home operators and their related companies for siphoning off between $16 million and $22 million in government funds using a complex corporate scheme straight from the private equity playbook. In addition to demonstrating poor care and low staffing, James’ office used forensic accounting to follow the money and expose fraud, offering a window into how other prosecutors can pierce private equity’s corporate veil.

“It’s going to be a model for other attorneys general, and it’s certainly a model for the Justice Department, so I think we’re going to see litigation get a lot more

sophisticated,” Harrington said. “But we need the gov ernment, the DOJ, to step up and really go after some of these worst owners.”

In Massachusetts, the attorney general’s office sued former executives of the South Bay Mental Health Center Inc. and its private equity owners, reaching a $25 million settlement. It was the largest publicly disclosed health care fraud settlement in the country, and the $19.95 mil lion paid by the private equity firm, H.I.G. Capital, was the most ever paid to resolve fraud allegations against health care companies in a private equity portfolio.

Kevin Lownds, the deputy chief of the Medicaid fraud division in the Massachusetts Office of the Attorney General, suggested that even though that suit didn’t involve a nursing home, prosecutors could apply the same approach—showing that a private equity firm is aware of violations, fails to correct them and exacerbates them—in future nursing home cases.

Rosemary Batt, the Alice Hanson Cook Professor of Women and Work at the Cornell University School of Industrial and Labor Relations, has studied ownership and investment in health care. She called South Bay “an extremely critical, path-breaking case.” It helps demonstrate that “private equity is the puppeteer behind the puppet,” she said. But, she added, the amount of time and resources that went into pursuing the South Bay case “shows how absolutely difficult it is to enforce these kinds of laws and to seek decent standards in health care.”

Some experts argue that the best way to address the harm caused by private equity ownership is to prevent it in the first place. “The number one preference is that they be totally barred from any investment in nursing homes,” Harrington said.

If absolute prohibition is unfeasible, less extreme measures could still address many of the most troubling aspects of private equity’s participation in the nursing home industry. Direct-care ratios and increased staffing minimums offer two levers to ensure that more helping hands are available for residents; both strategies are

LEX 21 Points of Departure

Antitrust enforcement offers another avenue for preventing private equity from expanding its stake in long-term care at the expense of patient safety.

being test-driven around the country. Last year New York established a minimum of 3.5 hours of nursing care per patient-day.

“How many decades do we need to have reports saying staff makes all the difference in the world for quality care before something is done?” Edelman asked, noting that the Biden administration has pledged to develop and enforce staffing ratios for nursing facilities. “Not surprisingly,” she continued, “the nursing home industry has already promised a massive campaign to defeat whatever standards the administration proposes.”

Care ratios would go a long way toward fixing the misaligned motives that allow profits to dictate how a nursing home is run, said Pam Walz. Public money shouldn’t be so easily converted to private gain.

“Resources are scarce enough without operating under a model where much of that money has to go to creating a profit for someone,” she said.

Scrutinizing nursing home owners more closely— including by establishing consistent criteria for eligibility to buy into the industry and devising a more meaningful five-star rating system—would allow consumers to steer clear of operators or facilities that don’t meet standards, experts say.

Given that it controls the purse strings for the industry, CMS could use its authority to tie reimbursement rates to metrics that would force nursing homes to improve their level of care, Allison Hoffman suggested. Studies have shown that when private equity acquires a nursing home, not only do staffing levels decline, but residents are more likely to be sent to an emergency room. Within the data lies an opportunity for what she calls “technocratic tinkering.”

“These things are measurable and tracked, so you could tie reimbursements more closely to the kinds of outcomes that you know private equity is going to fail on,” she continued.

Antitrust enforcement offers another avenue for preventing private equity from expanding its stake in long-term care at the expense of patient safety. Antitrust regulators have been “chasing” in the health care space, rather than leading, Allison Hoffman said, but updating laws to prevent private equity purchases from flying under the radar would give regulators more power to limit these firms’ share of the market.

“If you step back and look at what’s going on, it’s exactly the kind of structure, harm to competition and harm to consumers that antitrust law should be concerned about,” she said.

Ironically, the complex corporate structures that help private equity firms evade responsibility when things go wrong could be their undoing. Batt’s scholarship has focused on REITs, and she contends that there’s no reason these trusts should be able to deduct dividends paid to shareholders—one reason their use is attractive to private equity firms and part of why the nursing home industry has been a profit center for them.

But the increased attention to private equity ownership notwithstanding, none of the proposed reforms will matter, advocates argue, unless legislators and regulators are committed to enforcing them.

“If we enforced some laws, maybe these private equity people would say, ‘It’s not worth it, we can make money somewhere else,’ and they’d go away,” Edelman said, “because they really just care about extracting profits.”

Some critics have pushed back against regulators’ focus on private equity. In a joint statement issued March 11, 2022, the American Health Care Association (AHCA) and the National Center for Assisted Living (NCAL) argued that private equity’s impact on nursing homes has been exaggerated and its share of the market already declining. In addition, according to the AHCA and NCAL, private equity only got its toehold in the industry in the first place because low government reimbursement rates made it impossible for traditional operators to stay in the business.

“The lack of financial support for the industry from policy makers,” the statement reads, “has forced a small number of nursing home providers to sell off their assets and seek other revenue sources in order to keep their doors open for their residents and staff.”

22 Care Inc.

Rosemary Batt is a professor at the Industrial and Labor Relations School at Cornell University. She has written extensively about the impact of private equity investment on health care.

Nowhere to Hide

For nursing home employees, the work of caring for residents can be thankless. Underpaid and understaffed, they perform some of the most demanding labor in health care for some of the most vulnerable patients. It is, Furrow said, “a very different, very human industry” compared with those that have more famously attracted private equity dollars. Without enough nurses and aides in place, the risks are not only financial but potentially fatal.

“If you don’t have someone there at the bedside to manage the pain, it all falls on the family,” said Tara Sklar, faculty director of the health law and policy program at the University of Arizona James E. Rogers College of Law. “It’s really traumatizing, instead of something that could otherwise just be a natural stage of life.”

Scholars and advocates who have watched private equity firms squeeze profits out of the nursing home industry fear what will happen as their attention extends further into elder care. “The data has shown that private equity has in some ways finished exploiting the nursing home industry and moved onto other health care segments that impact the elderly,” David Hoffman said, highlighting hospice and home care as urgent concerns.

In the past decade, the number of hospice companies owned by private equity has quadrupled. In both hospice and home care, Sklar said, private equity ownership is likely to produce the same conditions that put patients at risk in nursing homes.

“These are all things that are happening disproportionately more when nursing homes are owned by private equity, and there’s no reason to think that wouldn’t be the case as they continue to expand into home health and hospice,” she said.

For their part, the AHCA and NCAL worry that private equity’s impact on health care will extend even further. According to their joint statement, “Private equity in health care is shifting away from nursing homes and into more lucrative sectors, such as dermatology and orthopedics. The issue is one for the entire health care system, not just nursing homes.”

The pressure is now on prosecutors, lawmakers and regulators to both use the tools already at their disposal— and also to design robust new methods—for holding private equity firms accountable for how they operate care-giving institutions.

“They’re in the spotlight now,” Furrow said, “and they can’t hide.” ■

LEX 23 Points of Departure

Ben Seal is a Philadelphia-based freelance writer whose coverage includes the environment, the law and academic research.

Scholars and advocates who have watched private equity firms squeeze profits out of the nursing home industry fear what will happen as their attention extends further into elder care.

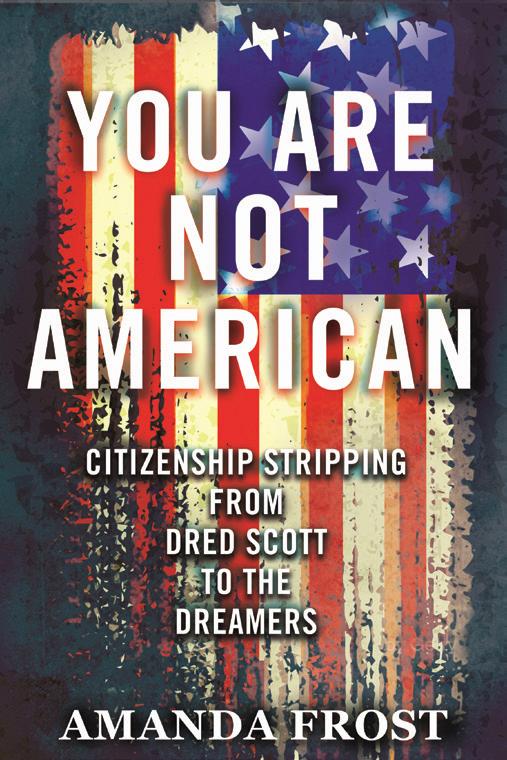

Amanda Frost is the John A. Ewald Jr. Research Professor of Law at the University of Virginia. Her writing and teaching focus on constitutional, immigration and citizenship law. She has written on a broad range of topics, from judicial ethics to the impact of nationwide injunctions, and has been published in numerous law reviews. Her work has also appeared in the New York Times, the Washington Post, The Atlantic and Slate, and she has testified before the House and Senate Judiciary Committees.

Frost was previously a law professor at American University, where she also served as acting director of the Immigrant Justice Clinic. Before entering academia, she clerked on the U.S. Court of Appeals for the D.C. Circuit and spent five years as a staff attorney at Public Citizen. She has also worked for the Senate Judiciary Committee and spent a year in France as a Fulbright Scholar studying transparency reform in the European Union.

Frost’s 2021 book, You Are Not American: Citizenship Stripping from Dred Scott to the Dreamers (Beacon Press), was named as a “New and Noteworthy” book by the New York Times Book Review

and was shortlisted for the Mark Lynton History Prize. In the book, she examines the little-known process of citizenship revocation in the United States through the experiences of a fascinating assortment of people over the course of 175 years, beginning with the story of Dred and Harriet Scott. The case of Dred Scott v. Sandford (1857) is perhaps best remembered for helping to precipitate the Civil War. But, Frost asserts, it was pivotal in defining who was and was not entitled to the rights and privileges of American citizenship. Over time, Frost explains, our essential understanding of who is an American evolved and broadened but not until thousands of Americans lost or were denied their citizenship for reasons ranging from marriage to a foreign-born man (for women) to having Chinese parents to labor activism.

Lex sat down with Frost earlier this year for a Zoom interview to discuss the history of citizenship stripping and what it tells us about our ideas of who is—and is not—a real American. The following transcript has been edited for brevity and clarity.

—Nancy J. Waters

A Q & A with Author Amanda

Frost

Frost

In your book, You Are Not American, and in several law review articles, you have explored the not-particularly well-known phenomenon of citizenship stripping, a process that has occurred with surprising frequency in the United States over the last almost 200 years. What first led you to mine this rich historical vein?

I think it was stumbling upon the story of Ethel Mackenzie, because I was really shocked when I learned that U.S. citizen women—naturalized or native-born birthright citizens under the 14th Amendment equally—lost their citizenship for marrying noncitizens under federal law. That law was in place for well over 20 years in the early part of the 20th Century. I had been teaching and practicing immigration and citizenship law for quite a while before I learned that. Mackenzie’s story really opened my eyes to the phenomenon of citizenship stripping.

And her story is so compelling because she was a leader in the Women’s Suffrage Movement in California. California women won the right to vote before the rest of the nation and really led the way. She was instrumental in achieving that and then she herself went to vote and was told, “No, you can’t vote because you married a non-citizen.” She challenged the law in a case that went before the Supreme Court in 1915 but lost.

Then, as I explored further this phenomenon of taking away citizenship, I discovered it happened again and again and again to so many different groups. I thought this history really needed to be better known.

A theme in the book is that people may lose their citizenship via an action—like Ethel Mackenzie, who married a noncitizen, although she had no idea that would happen. The best example is probably Fritz Kuhn, who lost his because he supported Hitler during World War II and advocated a Nazi regime in the U.S. But more often, it seems that the folks you describe in the book are stripped of their citizenship because of something more fundamental—their membership in a certain group. Could you tell us about some of those cases and what they tell us about who is and is not deemed to be an American?

Yes. And as an aside, I think the case of Fritz Kuhn— and there are a few other examples—raises some hard

26 Deciding Who's American

questions about whether it is ever appropriate to take away citizenship.

But citizenship stripping was often based on immutable characteristics, most often race. We see that again and again. The first two chapters in the book are about the struggle for the citizenship of African Americans both free and, of course, the formerly enslaved. By definition slaves were not citizens, so at the end of slavery, it was key to grant citizenship to that group of people who were part of America from the beginning.

The incarceration of Japanese Americans during World War II and the coerced renunciation of their citizenship was another example. Yet another was the children of Chinese immigrants who fought for, and won, the right to birthright citizenship. In the book, I profiled the plaintiff Wong Kim Ark who won a case establishing birthright citizenship for the children of all immigrants in 1898.

As you point out in the book, the founders never explicitly defined within the Constitution what qualified someone as an American citizen—it was all implied. And the Supreme Court didn’t meaningfully address that question until the Dred Scott decision. I think most people understand the relevance of that decision with regard to putting the nation on a path to the Civil War, but what is its relevance with regard to the evolving definition of citizenship?

When we think about Dred Scott, we think about the lead-up to the Civil War, the huge divide in our nation over slavery, the moral crisis, the sectional crisis, the end of slavery. That’s appropriate—that’s the most important aspect of that case. But when slavery was abolished officially through the 13th Amendment at the end of the Civil War, the question remained: Who gets to claim citizenship in the United States?

The Dred Scott decision declared that no Black person, slave or free, could ever be a citizen of the U.S.

Chief Justice Roger Taney wrote that the authors of the Declaration of Independence—men like Thomas Jefferson—could not really have meant that all men were created equal while at the same time enslaving African Americans. The way he tried to reconcile that

great tension, that great American dilemma, that great hypocrisy, was to say that no Black person could ever be considered an equal member of our community. And when the Constitution’s framers wrote “We the people of the United States”—the first line of our Constitution— Taney concluded they could not have meant to include Black people within the “people” because our history was a history of enslavement. Significantly, Taney correctly identified the great hypocrisy of our nation’s founding. Tragically, he (and many others) sought to resolve that hypocrisy by rejecting membership for African Americans.

I think most of us knew that the 14th Amendment guaranteed citizenship to the freed slaves. But I was completely unaware that this was the first time that the guarantee of birthright citizenship was codified in the U.S. Constitution. You write that “its birthright citizenship clause was the great equalizer…birth in the Unted States was the cleansing act from which all emerged as caste-less equals.” Can you elaborate on the 14th Amendment and why you think it is so important?

We fought a Civil War to end slavery, but Reconstruction was about creating egalitarian membership for all inhabitants of the United States. The Reconstruction Congress realized that the nation needed to define citizenship and must define it in a way that includes everyone, regardless of race, regardless of class or lineage. The goal of the leaders of the Reconstruction—men often referred to as the “Second Founders”—was to end caste in America.

I’m writing a second book. I’m in the weeds of it and thinking about it all the time. It’s about the 14th Amendment’s birthright citizenship guarantee, tentatively titled Born in the USA. I did not intend for You are Not American to be entirely a depressing book—there are many stories in the book with happy endings! But I understand why people might perceive it that way. The second book will be more uplifting because birthright citizenship in the 14th Amendment transformed the nation’s understanding of itself.

LEX 27 Points of Departure

Birthright citizenship is about far more than some technical legal way to allocate citizenship. It’s about creating a caste-free society in which identity and status are cleaved from race, immigration status and lineage.

I think birthright citizenship is about far more than some technical legal way to allocate citizenship. It’s about creating a caste-free society in which identity and status are cleaved from race, immigration status and lineage. To be sure, the reality often falls short of this promise, but the power of the idea of equality at birth has nonetheless been transformational. Some scholars have described birthright citizenship as simply harkening back to a feudal English Common Law rule in which all born on land controlled by the king were his subjects, but I believe the citizenship clause in the 14th Amendment was instrumental to the egalitarian promise of the Reconstruction Era.

As you note in the book, the 14th Amendment was constantly challenged. One of the most important challenges was the case of Wong Kim Ark v. United States. Wong Kim Ark was born in the U.S. to Chinese parents and his citizenship was challenged as a test case in 1895. Can you tell me more about that case? And why don’t we all know about it?

This year is the 125th anniversary of that decision, and I’m going out to San Francisco to participate in an event commemorating this great Supreme Court victory. Yet the case remains little known, even among lawyers and law professors.

Wong Kim Ark was a milestone in the ongoing battle over who is an American, which is the theme of the book. It was also an attempt to use citizenship stripping to take away political rights. Many white Californians expressed concern that if the children of Chinese immigrants were citizens, they could vote, and might even run for office or be president. There was great fear about allowing nonwhites to exercise political power.

It was also a continuing battle over the meaning of the Civil War and the Reconstruction amendments. Holmes Conrad, the U.S. solicitor general who challenged Wong’s citizenship, was from a slave-owning family in Virginia, and had served as a Confederate officer during the war. There’s some irony there because, like other Confederate officers, he almost certainly lost his citizenship rights for some period right after the war, before gaining them back under President Andrew Johnson’s broad use of the pardon power. But Conrad would not have recognized that parallel! He viewed non-white people as not truly American and rejected the 14th Amendment’s egalitarian goals. In his correspondence about this case, he wanted

to argue that the only people who were not birthright citizens were the children of non-white immigrants.

But because the framers of the 14th Amendment knew well what the future might hold, they had put into the constitution this race-neutral definition of citizenship. So, Holmes Conrad was forced to argue before the Supreme Court that all children of immigrants were not citizens of the United States. The result would have been to strip citizenship from tens of thousands of Americans and to create a permanent caste of noncitizens descended from immigrants.

I fear the only reason Wong Kim Ark won is because his lawyers very carefully told the court, and the court repeated in their opinion: If you deny citizenship to Wong Kim Ark on the ground that the children of immigrants are not citizens, you are taking away citizenship from the children of Germans and Irish and English people too. That was clearly a part of the court’s rationale, if not the key. It was a close case—it took over a year to decide and that was longer by far than the average at the time.

Remarkably, 30 years after birthright citizenship was added to our Constitution, the question of who qualified for citizenship remained up for debate. Even today, former President Donald Trump, among other political leaders, has questioned birthright citizenship for the children of undocumented immigrants.

There’s this recurring theme that, “They didn’t mean it.”

The other theme is, “We don’t want these people to be our fellow Americans.” But each immigrant group Americans initially fear—from the Chinese to the Japanese to the Irish to the Italians—we eventually embrace. What were we afraid of? I’d like to think we could learn a little from that.

One of the things that strikes me in the book is that these citizen-stripping cases put “the strippers” in the position of making some crazy, inconsistent and illogical arguments, i.e., as you just described, Taney’s reasoning in his Dred Scott opinion or Conrad’s argument in Wong Kim Ark. Another was the argument that women should not keep their citizenship if they married foreign men because of the foreign man’s corrupting influence—but they didn’t lose their citizenship if they married a naturalized foreigner? Or a native-born American criminal? Do you think there

28 Deciding Who's American

Because the framers of the 14th Amendment knew well what the future might hold, they had put into the Constitution this race-neutral definition of citizenship.

is something about citizenship questions in general that engendered illogic, inconsistency and hypocrisy?

itizenship laws embody all of these assumptions that we have about what it means to be an American, about inheriting Americanness from family members, about the role of mothers and fathers in transmitting American values, about how you might gain your Americanness from different stages of your life. These are messy, existential questions that we struggle to answer in ways consistent with our nation’s values.

So, for example, under the law today, a U.S. citizen married to a non-citizen can only transmit their citizenship to their child born outside the United States if the U.S.-citizen parent lived in the United States at least five years, and at least two of them over the age of 14.

The idea behind the law is that the parent who leaves the United States before age 14 never fully absorbed American values. By the way, I don’t disagree with that as a general proposition. I have a 10-year-old and a 13-yearold, and the 13-year-old is much more out in the world and influenced by her peers and her culture than the 10-year-old, who is much more at home with us. But the reason I note that law in place today—which I don’t have a problem with—is that citizenship laws reflect a society’s understanding of itself, its values, its idea of the family, its idea of how the society influences a child, and how to transmit societal values to the next generation. These are existential questions. Who do we want to be? And how do we shape our children into productive and engaged citizens in the nation?

Citizenship and immigration laws reflect these values, but especially citizenship stripping. It speaks even more loudly to say to an individual or a group: You are not an American. We exclude you. That act by itself is very much definitional. It’s a proxy for taking away political rights, and it’s an attempt to define the rest of us who remain behind.

I noticed in the book that you referred to the rules for renouncing your American citizenship and that naturalized Americans cannot renounce their citizenship in the middle of a war. Is that to prevent them from joining the enemy’s army?

Those are really interesting rules. Renunciation is something that the U.S. embraced long before other countries.

It reflects the American philosophy that the people consent to be governed, and they can choose to leave. The American Declaration of Independence was one great citizenship renunciation document: “We are not you. We are becoming our own nation.”