Race, Infrastructure and the Law

Aziz Huq on Collapse of Constitutional Remedies Law Degrees

THE MAGAZINE OF DREXEL UNIVERSITY THOMAS R. KLINE SCHOOL OF LAW

Danielle Conway on Antiracism

Dana Remus on Taking Chances Kalhan on Immigration and the Judiciary

2022

Undergraduate

Anil

Infrastructures

3 Dean’s Welcome Daniel M. Filler 4 At the Crossroads of Justice: Race, Infrastructure and the Law Wendy Gibbons 12 Rights Without Remedies: A Q & A with Author Aziz Z. Huq 20 The Law Is Too Important to Be Left to the Lawyers: The Return of the BA in Law Analisa Goodmann 28 Judicial Illiberalism: How Captured Courts Are Entrenching Trump-Era Policies Anil Kalhan 36 Building an Antiracist Law School Danielle M. Conway 42 Peeking into the Black Box: Exposing Barriers to Arbitrator Diversity Nancy J. Waters Contents U City Digest News from Kline Law 48 White House Counsel Addresses Graduates 51 Kline Launches Black Alumni Association 52 Law and Tech Center Has Busy First Year 54 Conference Explores Visual Information and the Law Inside Back Cover Alumni in Compliance Infrastructures

Rights Without Remedies: A Q & A with Author Aziz Z. Huq

At the Crossroads of Justice: Race, Infrastructure and the Law

Wendy Gibbons

The Law Is Too Important to Be Left to the Lawyers: The Return of the BA in Law

Annalisa Goodmann

Judicial Illiberalism: How Captured Courts Are Entrenching Trump-Era Policies

Anil Kalhan

Danielle M. Conway

Peeking into the Black Box: Exposing Barriers to Arbitrator Diversity

Nancy J. Waters Building an Antiracist Law School

4 12 28 20 36 42

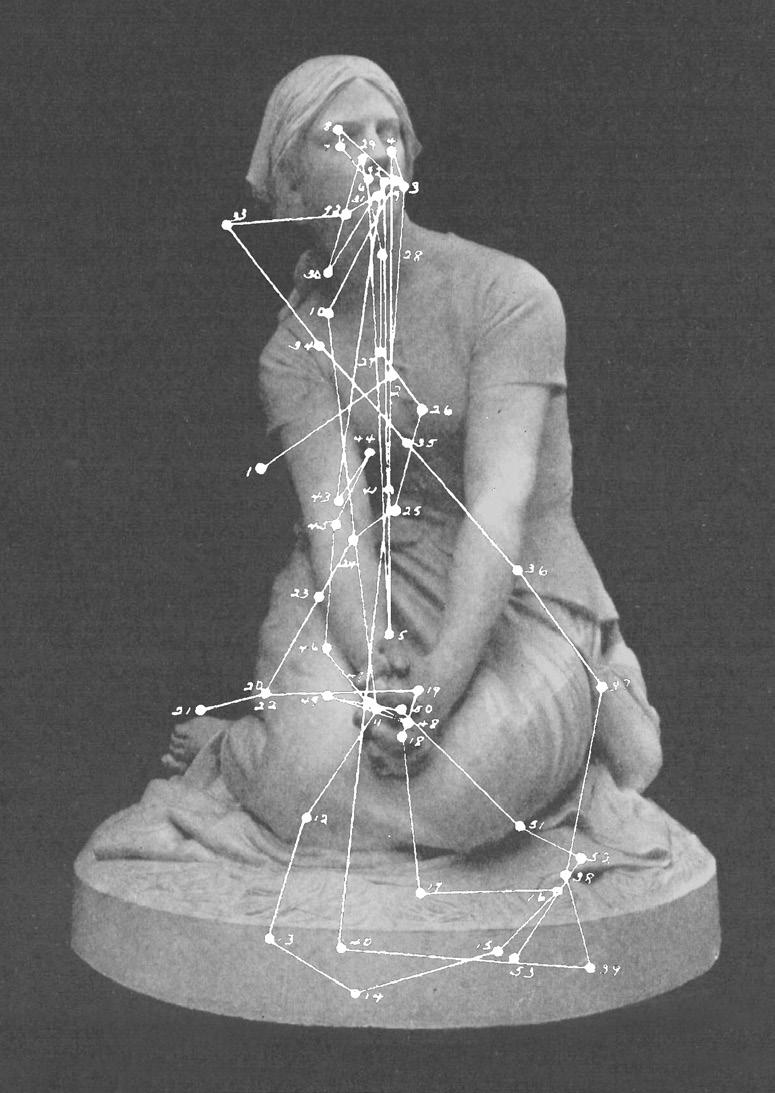

LEX: The Magazine of Drexel University Kline School of Law Fall 2022 Dean Daniel M. Filler Managing Editor Nancy J. Waters Creative Director Brian Crooks Art Direction & Design James Goggin, Shan James Practise Proofreader Purnell Cropper Type Metric 2, Tiempos Text (Kris Sowersby, Klim Type Foundry) Printer Brilliant Graphics Front cover, clockwise from top left: Wikimedia Commons/Eekiv (Creative Commons AttributionShare Alike 3.0); Daniel Williman; Architect of the Capitol; Practise 3: Zave Smith Photography 4: Adobe Stock/Elephotos 6, left: Whitney Thomas 6, right: Pixelsquid 7, left: Simona Corbi 7, right: American Society of Civil Engineers 8, top: Kelly Johnson 8, bottom: Zave Smith 9: Adobe Stock 10: Avi Loren Fox Photography 11, top: Ellie Photo 11, bottom: Adobe Stock 12: University of Chicago Law School 13: Practise 14: Oxford University Press 15: Architect of the Capitol 17, 19: Practise 20: iStock 21: Vanderbilt University Special Collections and University Archives 22: Practise 23: College of William and Mary Law School Scholarship Repository 24, top: Daryl Peveto 24, bottom: Melissa Logan Haun 25, top: James G. Milles 25, bottom: James E. Rogers College of Law, University of Arizona 26, top: Zave Smith 26, bottom: Halkin/Mason 27, left: Kirill Sosonkin 27, right: Jishan Ahmed 28–29: Wikimedia Commons/Eekiv (Creative Commons AttributionShare Alike 3.0) 30: Adam Schultz 31: Executive Office of the President of the United States 32: Federalist Society 33: Shutterstock/David Peinado Romero 34: Shutterstock/ Vic Hinterlang 36–37: Brian Crooks & Practise 36: Daniel Williman 37: Penn State Dickinson Law 38: Wikimedia Commons/Tony Webster (Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 2.0 Generic) 39, clockwise from top left: Michelle Bixby; Howard University School of Law; Nick Romanenko; Doug Levy; Washburn University School of Law 41: Penn State Dickinson Law 42: iStock 44: Purnell Cropper 45: Practise 46: Tamara Shopsin & Jason Fulford 49, top: Tamara Shopsin & Jason Fulford 49, bottom: Purnell Cropper 50: Purnell Cropper 51, top: Fox, Rothschild LLP 51, middle: Tamara Shopsin & Jason Fulford 52: Tamara Shopsin & Jason Fulford 53, top: Purnell Cropper 53, bottom: Beke Beau 54, bottom: Tamara Shopsin & Jason Fulford 54–55: Charles Joseph Minard 56: Guy Buswell The Drexel University Kline School of Law publishes LEX once per year. Printed on FSC certified paper. Editorial Offices 3320 Market Street, Philadelphia, PA 19104 Telephone (215) 571-4804 Email lawdean@drexel.edu LEX Photography and Illustrations

Dean’s Welcome

Infrastructure has been a much-discussed topic over the past decade or so, but these discussions rarely connect infrastructure and the law or take into account the legal aspects of infrastructure or the infrastructural aspects of the law. But the two are, in fact, tightly entwined.

Infrastructural policies express societal priorities. From when to repair a bridge to where to site a highway, from how much to spend on a new school to how urgently to fix a lead-tainted municipal water supply—infrastruc tural decisions tell us both what matters to a society and who has power within that society. Is it getting workers to the office quickly? Is it limiting damage to the environ ment? Is it education, health care, recreation, the arts? Is it safety, efficiency, aesthetics? These choices are justice choices, and justice is ground zero for the law.

The injustice of racism persists for reasons beyond individual prejudice—it’s built into social, economic and political infrastructures. And it’s expressed by the pres ence of toxic waste sites and the absence of trees, parks, grocery stores and transit hubs. Conversely, efforts to address racial injustice by improving the law depend on legal infrastructures, the formal and informal rules and elaborate procedures by which we create and enforce laws and mete out justice, from legislatures to courts to police stations—to law schools. Our democracy rests on a massive legal infrastructure—and, as the last few years have shown, the rebar is beginning to bend.

This nexus between infrastructure and the law seemed ripe for investigating; thus, the theme of this fifth issue of the Drexel University Kline School of Law’s magazine, LEX : Infrastructures.

In the lead-off article, Wendy Gibbons explores infra structural justice writ large, with a focus on race. Most readers will be aware that Black, Latinx, Indigenous and immigrant communities bear a heavier burden when it comes to the health impacts of pollution, for example. But, as Gibbons reports, the impact of infrastructural injustice goes far beyond the realm of toxic torts, encompassing everything from potholes to broadband to municipal sewer liens. Gibbons focuses on what activist lawyers and law students can do to help these communities secure infra structural justice.

The United States Constitution, of course, provides the fundamental infrastructure of this republic. The foun dation has cracks, and they seem to be getting bigger—or maybe we’re just noticing them more readily. In this issue’s

interview, Nancy Waters spoke with constitutional scholar Aziz Huq of the University of Chicago to discuss his most recent book, The Collapse of Constitutional Remedies. The Constitution’s guarantees of individual rights mean little when violations can’t be remedied, which Huq reports is too often true, and he traces the problem back to the origins of our system.

This issue also features a look at the infrastructure of legal education. The juris doctor degree that we all know and love, Analisa Goodman reports, is a relatively modern invention. Law schools once routinely educated undergraduates—and the undergrads are back! Goodman traces the rise of the bachelor’s degree in law at law schools including here at Kline, where our new undergraduate law major launches this term.

Also in this issue, Kline Law Professor Anil Kalhan takes a deep dive into the now twisted infrastructure of a once humane and stable U.S. immigration system. Kalhan argues that Donald Trump blew the house down, Joe Biden has struggled to pick up the sticks, but Trump-appointed judges won’t allow him to exercise his executive authority to rebuild the system.

In the days following George Floyd’s murder, Dean Danielle Conway reached out to a quartet of fellow Black women law deans. First, they commiserated. Then they got to work dismantling structural racism by focusing on law schools—the institutions they understand so well. The ambitious AALS Law Deans Antiracist Clearinghouse Project was the result of their efforts. In her essay, Conway documents the arc of this pathbreaking project.

Our last feature article looks at a less discussed ele ment of our legal infrastructure: mandatory arbitration.

FINRA is working to diversify arbitrator pools for investor disputes, and Kline Professor Nicole Iannarone set out to test the success of these interventions. Along the way, she enlisted students in her research, creating a different kind of summer associate experience and helping her students salvage the otherwise lost pandemic summer of 2020.

Law schools play an important role in examining and refreshing our nation’s legal infrastructure. I hope this issue of L EX documents and advances that project. If you were activated, intrigued or even irritated by these articles, I’d love to hear about it. And I always heartily welcome any and all suggestions. ■

Daniel M. Filler LEX Infrastructures 3

At the Crossroads of Justice

By Wendy Gibbons

By Wendy Gibbons

Race, Infrastructure and the Law

Black, Latinx, Indigenous and immigrant communities in the U.S. suffer disproportionately from decaying and inadequate infrastructure and bear a heavier burden from pollution and the impacts of climate change. What can be done to address infrastructural injustice?

Communities of color have long contended with per vasive risks originating in the places they live, work, learn and play. Black, Latinx and Indigenous people suffer from higher rates of asthma and heart disease as a result of air pollution; they are more likely to die as pedestrians because of inadequate sidewalks and public transit; and they are far more likely to die in fires in overcrowded build ings that don’t meet fire safety standards. These threats represent just a handful of the deadly impacts of infrastruc tural injustice.

“The way that [people] breathe the air every day, it’s an integral part of racism because you can’t see it, but people are dying,” Brown said. She plans to put her degree from the Drexel Kline School of Law as well her talents for writing and advocacy to work at the intersection of racial and envi ronmental injustice. Of this intersection, she said, “I’m so pleased that more people are talking about it now.”

Infrastructural justice is a relatively new concept. It encompasses not only cases in which the harm of pollution falls disproportionately on some communities but also the unfair distribution of public infrastructure benefits, such as access to public transit, recreational facilities, high speed internet and good infrastructure jobs. From safe drinking water to clean air, dependable public transpor tation and healthy schools, both the benefits and the costs of everything we build are unfairly distributed, according to those who study these dynamics.

Algernon Austin is the director for race and economic justice at the Center for Economic and Policy Research (CEPR) in Washington, D.C. “These are,” he explained, “in many cases, life and death issues. Infrastructure writ large is stratified by class and race.”

Environmental justice is simply the best-known face of infrastructural justice—as a movement, it has been around since before Brielle Brown was born. In 1982, the NAACP led six weeks of protest in the majority Black community of Afton, N.C., after the state dumped PCB-laced soil there. More than 500 protestors were arrested, including Congressional Representative Walter Fauntroy and long-time civil rights activist Benjamin Chavis. Protestors argued that their com munity had been targeted for toxic waste disposal precisely because it was a majority Black community whose mem bers lacked political power. Then, in 1987, the United Church of Christ published a seminal report highlighting the fact that three out of five Black and Hispanic citizens in the U.S. lived in close proximity to hazardous waste sites.

In 2021, Austin authored a report investigating the links between infrastructure and race for the NAACP ’s

Thurgood Marshall Institute. The report highlights both the vast scope of the problem as well as the importance of framing the solution as an investment, not an expense. Rectifying these infrastructural inequities could cost as much as $2.59 trillion, which, Austin argues, is far less than the billions these conditions cost the country in reduced exports and trillions in reduced GDP and lost wages from unemployment and underemployment.

The American Society of Civil Engineers ( ASCE ) defines “infrastructure” more broadly than the roads and bridges that come to mind when most people hear the term. Every four years, the society produces a national report card that grades the country on 17 categories of basic ser vices, from railways to hazardous waste to schools and— most recently—broadband.

In 2021, the ASCE awarded U.S. infrastructure an overall C minus, with a disproportionate number of

Brielle Brown, JD ’22, plans to work on environmental justice issues.

Brielle Brown, JD ’22, has pursued a career in law because she wants to save lives. Growing up Black in Philadelphia, she became all too aware of the deadly effects of racism in the form, for example, of lethal police force. The people she hopes to protect, however, face even more inescapable if far less well-known threats: the daily risks of breathing, commuting and inhabiting while Black.

6 Race, Infrastructure and the Law

shortcomings found in communities of color. Seventyfour percent of the 200 people who died in Texas in 2021 when the electrical grid shut down following a major winter storm were people of color. And in Mississippi, according to the ASCE report, 43 percent of the roads are in “poor con dition,” contributing to one of the highest roadway fatality rates in the nation. Poorly maintained roads also increase the likelihood of vehicular damage. In Southaven-DeSoto County, Mississippi, for example, in 2019 the average annual vehicle repair cost of $1,870 represented six per cent of the annual median income for Black Mississippi residents, putting repairs out of reach for many residents and further challenging their ability to get to work, to the doctor or to a polling place.

The report card also cites the 400-plus Mississippi bridges that have been closed because they are unsafe, the Louisiana levees at substantial risk of failure and

Algernon Austin directs the Race and Economic Justice program at the Center for Economic and Policy Research in Washington, D.C.

The 17 Major Infrastructure Categories as defined by the American Society of Civil Engineers

Black, Latinx and Indigenous people suffer from higher rates of asthma and heart disease as a result of air pollution, and they are more likely to die as pedestrians because of inadequate sidewalks and public transit.

New York City’s estimated $45 billion public housing repair-and-maintenance backlog.

According to a 2018 Environmental Protection Agency ( EPA ) study, Black people are exposed to 1.5 times the amount of sooty particulates produced by burning fossil fuels for energy and transportation as the general popu lation. Notably, this study controlled for income, finding that the disparity was significantly larger for race than for income. Particulate exposure increases the risk of preterm births, asthma, cancer and heart disease.

For Indigenous communities, Austin said, climate change threatens cultural devastation. In states like Louisiana, Florida and Washington—and especially in Alaska—many tribes may soon be forced to move to avoid rising seas. Some 31 Native Alaskan communities face imminent displacement, and four already are in the process of moving, according to a 2009 report by the

Drinking Water Energy

Hazardous Waste Ports

LeveesInland Waterways

Public Parks Rail

Roads Schools Solid Waste

Stormwater Transit Wastewater

Bridges

Dams

Aviation

LEX Infrastructures 7

U.S. Government Accountability Office. And the altered migration patterns of the animals that Alaskan natives have traditionally hunted, such as bearded seals and whales, as well as shoreline erosion from thawing per mafrost and storm surge threaten their traditional ways of life.

Austin uses the parable of the four blind men and the elephant to illustrate why infrastructural injustice contin ues to plague so many communities of color. Infrastructure forms a foundational part of our lives, he explained, but we only see what is right in front of us, limiting our under standing of the big picture. To maintain its position as a world-leading, prosperous democracy, the United States, he wrote, must use its resources strategically to remedy longstanding racial inequities, rather than allowing huge sectors of our economy to be dragged down along with the well-being of millions of Americans.

Blocked Roads to Justice

The Grand Calumet River in Illinois is one of the nation’s most polluted rivers.

Kline Law Professor Alex Geisinger has taught environ mental law for more than 20 years.

Lawyers, activists and policy makers who seek to remedy infrastructural injustice confront significant hurdles. Alex Geisinger is a professor at the Kline School of Law and has taught environmental law for more than two decades. Alongside some of his law students, he has gone up against such powerful corporations as U.S. Steel. In 1997, he and his students filed a “notice of intent” to sue that company over its potential contamination of the Calumet River in Illinois. Eventually, the EPA got involved and reached agreement with U.S. Steel to develop a corrective action program. Geisinger called the decision to take on one of the largest steel producers in the world “a deep breath moment,” but he has taken a deep breath and dived in a number of times throughout his legal career.

Typically, he explained, the first major challenge for grassroots organizations suing for redress in an environ mental case is also the most obvious one: marshalling the resources to take on their more well-funded corporate adversaries. Plaintiffs, Geisinger said, often need to build their own infrastructure of “people to support the legal work.” Consequently, he continued, “change tends to hap pen glacially.”

For communities of color, however, the relative disadvantages in wealth and power are even more stark. Moreover, in environmental cases, advocates have found their access to the courtroom blocked by judicial prece dent. Plaintiffs who attempt due process or discrimination claims under Civil Rights laws such as the Equal Protection Clause of the 14th Amendment face significant challenges under case law, Geisinger explained.

In the 1977 case Village of Arlington Heights v. Metropolitan Housing Development Corp, the United States Supreme Court upheld a zoning ordinance that prevented construction of racially and economically diverse housing

outside Chicago. The court’s majority opinion stated that because states and municipalities must balance numerous competing factors in siting decisions, the courts should only interfere if plaintiffs can show that racial bias was a motivating factor. Individuals seeking to prevent permit ting of polluting facilities near their homes, for example, must prove not just that the facility will disproportionately affect their community but also that the government’s decision to issue the permit was racially motivated.

Case law also limits lawsuits under Title VI of the 1964 Civil Rights Act, which outlaws discrimination based on race, color, religion, sex and national origin. In the land mark 2001 Alexander v. Sandoval case, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled for the Alabama Department of Public Safety over Martha Sandoval. Sandoval, a Hispanic woman, had filed a class action suit under section 602 of Title VI alleging that the department’s policy of providing driver’s permit tests exclusively in English violated the act’s prohibition against using federal funds to discriminate on the basis of national origin.

Justice Antonin Scalia, writing for the majority, stated that Section 601 of Title VI prohibits only intentional dis crimination and not disparate impacts occurring under state laws. He also specified that Section 602 does not include a right of private action that would entitle individuals to sue under Title VI. Although Alexander v. Sandoval was not an environmental case, it nonetheless “ripped the racial side of environmental justice regulations out from under the lawyers,” said Geisinger. “It laid that initial landscape.”

Additional federal court decisions have barred pri vate individuals from bringing disparate impact claims under Section 1983 of the Fourteenth Amendment, which prohibits the use of state law to deprive an individual of rights guaranteed under the U.S. Constitution. In South Camden Citizens in Action v. New Jersey Department of Environmental Protection, the Court barred private indi viduals from bringing disparate impact claims, and, in the 2002 Gonzaga v. Doe decision, it required Congress to clearly and unambiguously specify a right of private action for disparate impact claims in future legislation.

With most environmental justice litigation neu tralized by case law, administrative complaints offer an alternative. The federal Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) fields the majority of these complaints, but a 2016 report by the United States Commission on Civil Rights described the EPA’s Office of Civil Rights’ handling of such cases as “pathetic.” Between 1993 and 2015, not one of almost 300 complaints earned a formal finding of discrimination, and the commission could not identify a single case in which the office withdrew funding from entities accused of discriminating against low-income communities. For example, in a 2013 case, a local gov ernment successfully ignored the potential effects of a slaughterhouse on nearby homes owned or rented by low-income seniors and Black and Hispanic people. The 2016 report recommended that Congress increase funding for the EPA’s Office of Civil Rights specifically to increase staffing levels, so that the agency could better meet its own deadlines and improve its poor record of handling citizen complaint.

Recently, environmental justice advocates have had some success making the argument that some communi ties have borne disproportionate burdens from polluting or otherwise harmful projects and that these “cumulative impacts” should be considered in siting new projects. For example, in late 2020, residents of Chicago’s Southeast Side filed a complaint with HUD and a Title VI complaint with the EPA over the city’s proposed relocation of a metal recy cling facility near a park and high school in their neighbor hood. Activists even resorted to a 30-day hunger strike to get the city’s attention, finally succeeding in convincing the Chicago Department of Public Health to leave the per mit pending until the city, assisted by the EPA , completes a health impacts analysis of the neighborhood.

Where the federal government falls short, states rep resent another front in the battle. California, for example, has developed a screening tool to help identify commu nities facing multiple environmental burdens. And in September 2020, New Jersey community advocacy efforts drove passage of the nation’s first comprehensive cumula tive impacts law, which uses applications for new permits or permit renewals as a gatekeeping step for managing environmental impacts on overburdened communities.

The state is developing a screening tool similar to the one used in California to identify these communities, and the permitting process requires that applicants in those communities show that they will either produce no new

With most environmental justice litigation neutralized by case law, administrative complaints offer an alternative.

LEX Infrastructures 9

pollution, or that they can offset any pollution they do pro duce to reduce the existing overall pollution levels. In March 2021, Massachusetts followed suit. “For me, the real prov ing grounds… is what happens with these states that have adopted these cumulative impacts laws,” Geisinger said.

The Fight for Essential Services

Shelter is an essential—perhaps the most essential—component of every society’s infrastructure. Long before there were roads, bridges and dams, there were caves, tents and huts. The Federal Fair Housing Act of 1968 was created to combat the inequities that have long plagued the American housing market by prohibiting discrimination by land lords, real estate companies and lending institutions. Lawsuits and administrative complaints brought to the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) have helped combat discriminatory housing policies, but the significant segregation of minority communities in urban food deserts and industrial wastelands persists.

Kline Law professor Richard Frankel directs the school’s clinical and experiential education programs, which give law students opportunities to advocate on behalf of underserved communities. “Housing, to me, is such a big issue,” he said, citing the January 2022 public housing fire in Philadelphia that killed 13 people, poi gnantly illustrating the intersection between poverty, infrastructure, race—and life and death. “People died,” Frankel said, “because the housing was overcrowded.”

Access to clean running water also depends on infra structure, and here also, communities of color confront greater burdens and risks. In 2016, research by students from Kline’s Andy and Gwen Stern Community Lawyering Clinic, for example, described water shutoffs in several predominantly Black West Philadelphia communities that have forced residents to lug jugs of water home from the store to meet their basic needs.

According to Algernon Austin of the CEPR , water affordability is a particular problem in racially diverse

areas of the United States. A 2019 report by the Thurgood Marshall Institute (TMI) examining race and water afford ability stated that in cities such as Cleveland, Baltimore and Flint water liens have disproportionally affected Black residents, leaving them not just thirsty but also at greater risk of getting evicted, losing custody of their chil dren and even facing criminal charges. In Baltimore, for example, residents with unpaid water bills as low as $350 have had liens placed on their homes, a policy that has contributed to decreasing homeownership in the majority Black city.

According to the TMI report, “Municipal discrimi nation in the provision of water services runs deep.” The report’s authors argue that such local policy changes as banning lien sales, water service disconnections and the privatization of essential public services such as running water, would limit the need for litigation to resolve these infrastructural inequities.

In Philadelphia, such policy changes have made a difference. Following a coordinated campaign led by Community Legal Services of Philadelphia (CLS) in 2016, the city established several water affordability plans for protecting low-income homeowners from water shutoffs. In coordination with that effort, Kline’s Stern Clinic worked to resolve a problem many of its clients faced: lack of run ning water in homes with title issues, explained Rachel López, the clinic’s director. “Partnering with community members and other stakeholders,” she said, “we suc ceeded in compelling the Philadelphia Water Department to change the outdated policies that prevented residents from addressing back payments on their water bills while they were trying to clear title to their homes.”

“We also recently learned,” she continued, “that our advocacy was instrumental in the Department of Health’s push to have a moratorium on water shutoffs during the pandemic and reconnect those who were already cut off.”

To the ordinary person, infrastructure is nearly syn onymous with transportation, and large federal infrastruc ture bills are often known as “Highway Bills.” Kate Lowe, an associate professor of urban planning at the University of Illinois, Chicago, has researched transportation inequi ties and policies to address them. The 2021 Infrastructure

Shelter is an essential— perhaps the most essential— component of every society’s infrastructure. Long before there were roads, bridges and dams, there were caves, tents and huts.

Diana Silva, JD ’11, practices envi ronmental law in Philadelphia.

10 Race, Infrastructure and the Law

Investment and Jobs Act—otherwise known as the “Infrastructure Bill”—includes a “Justice40” initiative requiring federal agencies to work with states and munic ipalities to deliver at least 40 percent of new benefits in climate and clean energy to disadvantaged communi ties, and these benefits often take the form of transporta tion-related projects. The policy is already being applied to everything from electric buses in Arizona to low-impact ATV trails in Alaska.

But according to Lowe, the infrastructure bill uses grant programs to award funds competitively, favoring municipalities with strong connections to state and federal lawmakers. Low-income communities, even those with strong nonprofits advocating for equity, typically find it more difficult to build those connections. Lawyers can make sure there are “diverse actors in the room,” when deci sions about how to spend federal dollars get made, she said.

The Next Generation of Advocates

Diana Silva, JD ’11, practices environmental law in Philadelphia. “There is a ton going on right now in the legal and regulatory world,” she said. The new policies have “lofty goals, but the devil is in the details,” she continued, and policies that appear beneficial can have unintended con sequences. For example, low-income neighborhoods with large minority populations often rely on nearby industrial facilities for jobs, she pointed out.

Silva is one among many Kline graduates and students who seek to apply their training for the public good. Before law school, Suzanne Chang, JD ’22, worked as a chemical engineer. Kline’s co-op program has helped her marry her scientific expertise on issues such as water contam ination with her legal training. Whereas STEM classes typically require “furious note-taking,” Chang finds the

more discussion-oriented law classes invigorating. In legal terminology, concepts like “reasonable” are abstract and situation-dependent, whereas in engineering, quantifi cation of standards sets clear boundaries, Chang said. Her expertise, she said, allows her to function as a “translator between engineers and lawyers.”

According to Kline’s Richard Frankel, more students see themselves as agents of change who want to make a difference in the world. “I think they really like seeing the impact of what they’re doing and getting out of the classroom,” he said. The key is forming lasting, credible relationships in local commu nities. These relationships, he continued,“take time to build and I think they’re really important.”

Victims of infrastructural injustice not only lack the means to engage in long and exhausting legal fights but also often the energy—they are simply too exhausted from bearing the daily burdens of these same injustices, whether from the struggle to breathe toxic air, to lug jugs of water home from the nearest convenience store or to figure out how to get to work when doing so requires taking three dif ferent buses.

“Because I look like them,” Brielle Brown said, “I have learned to take that seriously, to serve as that voice.” Law school classes focus on “hard skills,” she explained, but Kline’s co-op experiences give students the opportunity to practice careful listening and to learn how to coach clients through difficult experiences. “You can’t get anywhere without that,” she continued. People who believe their rights have been trampled upon by the legal system may, understandably, be skeptical of lawyers. Effective advocacy requires knowing clients’ full, nuanced stories. For Brown, asking the hard questions is “part of my job.”

“That’s what our law school is!” Geisinger agreed. “We like to see the law in action, and our students are similar.” ■

Wendy Gibbons is a science educator, freelance writer

Suzanne Chang, JD ’22, worked as a chemical engineer before law school.

LEX Infrastructures 11

Rights Without Remedies

A Q & A with Author Aziz Z. Huq

Aziz Z. Huq is the Frank and Bernice J. Greenberg Professor of Law at the University of Chicago and a scholar of U.S. and comparative constitutional law. He has written on topics rang ing from the rise of authoritarianism and decline of democra cies around the world to the regulation of artificial intelligence. He is the author, with Tom Ginsburg, of How to Save Democracy, which won the International Society of Public Law I-Con Book Prize in 2019. He clerked for Judge Robert D. Sack of the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit and for Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg of the Supreme Court of the United States.

In his most recent book, The Collapse of Constitutional Remedies (Oxford University Press 2021), Huq takes a close look at what happens to individuals who seek to use the fed eral courts to vindicate the basic rights they believe are guar anteed through the United States Constitution.

In fact, he argues, the court so rarely grants remedies to plaintiffs who have, for example, been unjustly harmed by police, that these rights have little practical effect, leaving individuals largely unprotected from the coercive power of the state. He contrasts these cases with the much more favor able treatment that corporations and other powerful entities receive when challenging the regulatory powers of federal administrative agencies.

This yawning gap between what Americans believe are— or should be—their constitutional rights and the remedies they are actually able to achieve in court is, according to Huq, a problem whose roots go back to the failure of the judicial independence that the founders of the republic envisioned.

LEX sat down with Huq earlier this year for a Zoom inter view to discuss the federal courts, the state of constitutional remedies and alternatives for protecting rights under the existing system. The transcript below has been edited for brevity and clarity.

Nancy J. Waters

In your book, The Collapse of Constitutional Remedies, you suggest that, in the popular imagination, the federal courts act as a bulwark to protect individuals against the coercive and often even violent power of the state. In fact, you argue, the opposite is—and largely always has been—true: The courts typically fail to protect individuals from state power, and, moreover, curtail the government’s regulatory powers to protect individuals from corporations and other power ful actors. Can you give us some examples?

In the book, I give the example of a man called Alexander Baxter who was homeless and arrested by police. During the arrest, police officers set a police dog on him, and the dog seriously injured Baxter.

You would have thought that Baxter had a right under the Fourth Amendment against unreasonable force, and you would have thought that the egregiousness of the action taken by the police—setting a dog on someone who had put up their hands and surrendered—would have made this an easy case. Quite the contrary. The fed eral courts have established over the last 50 years a set of rules for when individuals get remedies in the face of state

violence, and these rules about remedies make it very dif ficult for people like Baxter to even get into court. Indeed, Baxter, whose case went all the way to the United States Supreme Court, never once got to state his case in court because of the doctrine of qualified immunity that pro tects police from liability for actions taken while on duty.

That’s just one example, but it’s representative in the sense that most people who are subject to acts of state coer cion don’t have an effective remedial pathway even if their treatment violates the Unites States Constitution. This is in stark contrast to the way that federal courts today treat cor porations and other regulated actors seeking to challenge a federal administrative agency’s actions. In this sphere, courts have made it much easier to get into court and to object on constitutional or statutory grounds to federal regulatory action.

An example of that is a case called Seila Law LLC v. CFPB in which a California law firm challenged the actions of the Consumer Finance Protection Bureau (CFPB ). Seila’s challenge was based upon the claim that the president of the United States lacked the authority to remove the CFPB ’s chair. Now, what’s striking about the Seila Law case is that the CFPB hadn’t charged Seila Law; it had just requested documents from Seila Law, but that was enough to get the firm into court.

Moreover, Seila Law couldn’t credibly say that the degree of presidential control over the agency changed the way that the agency treated the firm. That is, there was no connection between the constitutional claim that Seila Law was bringing and the actual way they were treated in that case.

Despite those two big differences between Seila Law’s case and Baxter’s case, the court allowed Seila Law’s case to go forward: It reached the constitutional question on the merits. The important point is that Seila Law got a hear ing on the merits and Alexander Baxter didn’t, and that’s reflective of a broader pattern in which the court has used the doctrine of remedies as a way of allocating the scarce resource of constitutional adjudication.

In the book, you note that John Locke and John Adams believed there should be no role for courts independent of both the legislature and the executive. Do you disagree?

Rights Without Remedies: A Q & A with Aziz Z. Huq14

Broadly, how would you characterize your conception of what the role of the federal judiciary in the United States should be, and, in any true democracy for that matter?

That’s a really hard question, and it’s not one that the book answers. I’m not sure I have a simple answer. What I would say is that, at the founding of the republic, there were dif ferent views about the role the courts could or should play in a polity. And there was an entirely serious view associ ated with both John Locke and a very influential French thinker called Montesquieu that independent judicia ries were not a necessary feature of a decent democratic government. That view was held to varying degrees by a number of people in the context of the debates over the ratification of the U.S. Constitution. On the other hand, other people involved in the ratification debates thought that independent courts were very important.

The point that I want to make about the ratification context is that the framers had a very specific understand ing of how independence would be achieved. It was an understanding of judicial independence that rested upon certain assumptions about background political and social conditions. It assumed, for example, that there would be a very, very small supply of qualified jurists. And it assumed that the U.S. Senate, in particular, would be a non-parti san body. The framers thought that they had designed a constitution that would eliminate political factions at the national level.

Neither of those two assumptions about limited sup ply of qualified lawyers or about the non-partisan nature of the Senate survived the first decade of the American Republic. In a sense, both of those assumptions were

victims of the success of the American project. But what that success meant was that the framers had crafted in Article III of the Constitution an institutional pathway to foster judicial independence that rested upon assump tions that were—by the 1800s—false.

So, it’s not so much that I have a view in the book about what the right way to design courts in a democracy is or what the right way to design independence is. Describing the ideal is often a hard task. It’s much easier to say that whatever the ideal is, we can see that some zone choices turn out to be incompatible with background circum stances and turn out to be self-defeating in one way or another. Within that zone of potential criticism, one can identify ways in which the design of Article III rests upon assumptions that are, I think, clearly no longer valid.

The vision of judicial independence in the Constitution is based upon the idea that there would be no possi bilities for partisan selection of judges at the front end and, therefore, the only kind of protection required was at the back end once judges were appointed, and that protection needed to focus on individuals rather than the judiciary as an institution. I think none of those assumptions turn out to be well founded, which sets the stage for where we are today with remedies.

In the book, you argue that remedies are so rare, they are almost non-existent, but that without a remedy there is no right. Does this mean our conception of individual rights in this “democracy” is an illusion?

I certainly think that with, for example, police violence, the difficulty of obtaining any kind of remedy under fed eral law means that it’s really hard to see how—outside of the truly exceptional cases in which death results—the police are constrained by constitutional law and consti tutional rules concerning force. I wouldn’t say that the right is an illusion—that’s not the way I would put it. But I would say that the right does not have much practical effect upon the way that the police behave. So, from the perspective of the citizen, the right might have theoretical value, it might have a dignitary value, but it doesn’t cash out as an expectation respecting the way that the state and its coercive actors actually behave.

Most people who are subject to acts of state coercion don’t have an effective remedial pathway even if their treatment violates the United States Constitution.

LEX Infrastructures 15

You said it has a “dignitary value.” Can you explain that?

Before the mid-1950s, the claims made by the Civil Rights movement to equal participation, particularly in Southern states, were claims that were not recognized as a practical matter—they were denied. But the fact that the Civil Rights movement at times—not always, but at times—could make its claims in constitutional terms clearly made a difference to the people involved in that movement and clearly made a difference to other people.

So that’s an example where you have a right that is not recognized under law, but that’s a right that has dignitary effects on people making the claim and also on third parties.

So, what we might call a symbolic effect has a cultural, social and psychological impact?

It might do or it might not do. But I’m trying to explain why “illusion” is not the word I would use to describe these rights.

In your book, you argue that this dynamic has been in effect since shortly after the founding of the republic. If so, is this really a collapse of the remedies themselves, or rather a collapse of our conception of our own rights as individuals? Are you arguing that something has happened recently—the last 25 years, say—where the remedies collapsed? I think you are suggesting that this dynamic has been ongoing.

think that the book is telling two different stories, and they have slightly different time frames. The first story is the failure of the assumptions that undergird our constitu tional vision of judicial independence. And that’s the story of what happened in and around the founding and, princi pally, the decades that followed. Because judicial indepen dence did not work in the way that the founders imagined, the judiciary has always been porous to partisan forces in a way that is not well captured in the public imagination. And those partisan forces have molded the judiciary in ways that reflect transient policy agendas. The judiciary is expanded when it is useful to a particular dominant polit ical party to expand the courts. This was especially true in

the 1870s when courts were used as a wedge to nationalize the American economy.

Federal courts turned out to be useful to a Democratic coalition in the 1940s and 1950s as a way of undermin ing Jim Crow without directly confronting Southern Dixiecrats. So, the courts became a way of effectively solving a problem that President Franklin Roosevelt had with his coalition in the context of the New Deal. Because courts played that role in the ’40s and ’50s, courts in that capacity expanded the remedial options that were avail able to individuals as part of the campaign against Jim Crow laws both in schools and in police stations and courthouses. The availability of remedies dramatically expanded starting at the beginning of the 1950s and endur ing to the 1970s.

So, the term collapse is appropriate because since the 1970s the availability of remedies as opposed to rights has been dramatically withdrawn, particularly for those populations that most benefitted from the Second Reconstruction. And again, this is a story about the respon siveness of the federal courts to changing national political coalitions. I think that people forget that the last time the Supreme Court had a majority of justices appointed by a Democratic president was at the beginning of the 1970s. So, we’ve had a majority Republican-appointed Supreme Court since the beginning of the 1970s. And the appoint ing presidents, starting with Richard Nixon, have had a very, very clear vision of what they want from the courts. Starting with Nixon’s “Law and Order” campaign, new Republican appointees to the Court focused on drawing back remedies, in particular in the policing and criminal justice context, which remains, I think, true today. So, in that light, I do think that the word collapse is appropriate, but the term is capturing one piece of a bigger story.

So, do you have in mind any specific reforms that could reshape the federal judiciary that could make it more dem ocratic and more protective of the rights of individuals?

First, the responsiveness of the federal courts to the interests particularly of the economically and socially marginalized really turns upon who wins political power in the Senate and the White House and who appoints federal judges. I think that we think of the courts as a counter-democratic institution or a counter-majoritar ian institution. But that’s not true in the sense that courts are responsive—and pretty quickly responsive in the scheme of things—to those national majorities. And the big changes that we’re seeing now in abortion, equality and Second Amendment cases is very clear evidence of that straightforward fact about American political life. So, at least in our current system, what matters is who gets elected, even for the courts.

The second thing I would say is that there are limits to what the federal courts as currently designed will be able to do, especially for people who are indigent, who are socially marginal, who don’t have the resources to bring cases or to influence the agenda of the federal courts. The book doesn’t talk about this, but there are reforms outside

It’s really hard to see how—outside of the truly exceptional cases in which death results—the police are constrained by constitutional law and constitutional rules concerning force.

Rights Without Remedies: A Q & A with Aziz Z. Huq16

I

of the courts that can be imagined that would make police departments in particular more law-abiding and rightsrespecting. This matters because police are numerically the most important violators of constitutional rights in the United States because they are the people most endowed with the power to coerce. That’s their job—their job has the highest risk of constitutional violations. That’s a neutral observation. I think there are ways of eliciting more constitutional behavior from police departments that would involve alternative mechanisms that are more effective than what we have now, and they don’t involve the courts.

I’ll give an example. There’s a set of tribunals that are outside of Article III, they are called Article I tribunals. An example is the U. S . Court of Claims, which hears claims against the federal government for cash. You can imag ine an Article I tribunal that would hear claims on the grounds that a particular police department had a pattern of practice of constitutional violations. You could imag ine that the qualification for sitting on that Article I body is that a person have had some experience either as a public defender or as a civil rights litigator so that they under stand the situation of litigants and that they understand the dynamics of those institutions. Our federal courts are massively biased toward prosecutors at the moment. You can imagine that Article I body would have the power to award damages to the group of people harmed by a police department’s unconstitutional conduct, but that it would also have the power to limit or to redirect the federal fund ing that flows to that police department. So, you could imagine that it would have not just the lever of a damages

award, but that it would have the lever of shutting off the spigot of federal funding, or saying, “You’re allowed to have federal funding but you’ve got to use it for use-offorce trainings and unless you have these use-of-force trainings, that’s it: You don’t get federal funding.”

So, is that the same dynamic as “defund the police”?

No. The defund-the-police claim is that it is just categor ically a mistake to rely upon policing to produce social order, and that the way you produce social order is that you invest much more in social services. There’s empirical evidence that this argument is true, at least sometimes, in the work of people like Patrick Sharkey at Princeton. But what I’m referring to is different because it doesn’t involve an absolute removal of funding from policing; it uses the funding that exists as a lever to change behavior and it focuses on the fact that federal funding has become an increasingly important part of what local police depart ments rely upon—so it’s quite different from the aboli tionist claim.

Would putting different incentives into collective bar gaining agreements with police unions or similar efforts be another kind of helpful reform?

This is a bit far from the argument of the book, but yes, I do think that changes to the structure of collective bar gaining agreements are important. In other work with colleagues, I have written about the actual content of col lective bargaining agreements and, in particular, about those provisions in collective bargaining agreements that benefit only bad actors within the police—provisions that all they do is allow bad actors to coordinate cover-ups. I think there is no justification for those provisions. That’s an example of something that can be identified pretty specifically and eliminated.

In a forthcoming piece with my colleague Robert Vargas of the University of Chicago’s sociology department, we’ve looked at why it is that policing reform—even in a big liberal city like Chicago—fails. And that has a lot more to do with the dynamics of how the mayor interacts both with the city council and with the police department. It has a lot to do with what makes a mayor popular or unpop ular and how dependent the mayor is on the police depart ment because of the role that crime plays in public opinion. [Editor’s note: You can find this article at papers.ssrn.com/ sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=4046125.]

That’s a quite different story, and I actually think it’s a more subtle story that presents difficulties for the straightforward abolitionist argument because it suggests that the abolitionist argument just focuses on the police department and doesn’t step back to ask, “Well, why does the police department take this path? Why does it have these attitudes and not others? How did this come to be and what role does it play in a larger political economy?”

On page 157 of your book, I found this quote, which I love: “Too many lawyers and scholars genuflect before the

At least in our current system, what matters is who gets elected, even for the courts.

LEX Infrastructures 17

federal court because their own professional standing is inextricably linked to the judges for whom they worked and the federal cases they have filed.” You are both brave and—I’m guessing—secure in your position to feel safe writing that kind of statement.

I think federal judges are pretty used to being criticized. And in a democracy with free speech, that’s as it should be.

Yes, but I think the bravery is in criticizing your colleagues. How would you fix this—in and out of the academy, with regard to scholarship, pedagogy and practice?

I don’t think there is any single fix. I’m not sure I have a view about how to change people’s attitudes within the bar. I do think that one kind of prediction that I would make is that the current Supreme Court in its policy preferences is pretty far from the median American lawyer. And I think that if the court pushes the envelope with respect to its pol icy preferences—I can imagine this occurring over not just abortion but over the rights of the religious to discriminate in ways that harm third parties—I think you can imagine such a gap emerging between the court and the bar that the court starts to lose the almost instinctual support that it has from the bar. If we live in a world where there’s a big, big gap between the beliefs of the bar and the beliefs of, at least, the Supreme Court, that creates a kind of tension.

With respect to the academy: The academy is very var ied. Probably, what I have to say is more applicable to the bit of the academy that likes to think of itself as elite, but I don’t want to subscribe to that word. I do think things like the Yale Law School scholarships that were just announced for low-income students are very important, and the dean there should be applauded for what she’s doing on that front. I think expanding and emphasizing the role of law yers in service of the indigent through clinics and non-clini cal programs is really important. The more that law schools think about what they are doing as training people to engage in a service to the public, that whether they work for the government or a public defender or a law firm, they are still, in some sense, public servants is really important.

Rights Without Remedies:

So, let me make sure I understand this: You would like to see more of a public-service emphasis in legal education?

I think that’s fair. I think that I would add that young law yers should have a sense of the full spectrum of people who experience legal problems, what their experience is. I think that it’s easier to be detached from the actual problems of actual people.

So, you are advocating that law students have more exposure to those people whose rights are denied?

That’s a nice way of putting it. And that connects it to the theme of the book correctly.

Would you argue that laws schools need to be explicitly saying something different about the federal judicial system?

I don’t think law schools should say much one way or the other. Occasionally they do, and it gets them into trou ble. Law is a very hierarchical profession, and I think law schools could do more to foster a non-hierarchical sense of achievement. For example, they could do more to celebrate publicly graduates who go into public service that power fully changes people’s lives and that this is maybe more important than getting appointed to something or other.

I think they should spend less time publicizing their links to powerful judges and politicians—but I recognize that I’m just whistling in the wind on that last point.

You had two federal clerkships. How much of your sense of disappointment with the federal judiciary arose from that close exposure or was this something that you developed later as a scholar?

Both of my judges, one of whom is still on the federal bench, were and are, I think, models, not just of what a lawyer and a judge should be, but of what a human being should be—in terms of their decency, their empathy and their care for what the law required and what the law was for as a social institution. I was tremendously lucky to work for such remarkable lawyers and human beings, and I wouldn’t have given up that experience for all the gold in the world.

I’m in the odd position of writing a book that’s very critical in many ways of the federal judiciary and dedi cating that book to the judge I clerked for who is still living, Judge Sack. I sent him a copy of the manuscript early on and said, “Look, I’m planning on mentioning you. Is that OK ?” And he was fine with it, but I have no idea whether he agrees with some, all or none of the arguments in the book.

I certainly think the experience that I had in work ing for those particular judges shaped my view of what makes a judge a good judge and what role a judge can play in a decent society. Although I don’t purport to speak for either of them—I think that both of them would say it’s perfectly fine to look at actual courts and express actual

Young lawyers should have a sense of the full spectrum of people who experience legal problems, what their experience is. I think that it’s easier to be detached from the actual problems of actual people.

A Q & A with Aziz Z. Huq18

disappointment that they don’t live up to the ideals that one wishes for them.

You were raised in England and first came to the United States as an undergraduate, correct?

I did. I came here as an undergraduate to go to the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

Do you think the experience of not having been raised here gives you a clearer perspective on the fault lines of American democracy and, in particular, our court system?

Ithink there are plenty of people who are born and raised here who have very clear perspectives. I don’t think it’s nec essary to be an outsider to have a sense of what you call the “fault lines” in a society. There are plenty of people internal to a society who have a very sharp sense of that. Conversely, I think there are many people who come to another country and wrap themselves in and embrace the myths that the country tells of itself. I don’t think there’s any connection between being an outsider or a newcomer to a place and seeing it in a distinctive way.

One of the things I tell my law students is that when I walked into my first constitutional law class, I was quite green. I had grown up in a country without a written

constitution. I had not studied politics or taken any con stitutional law classes in college. I didn’t really have a sense in college that this was an important topic or didn’t really understand why. I turned to the person I was sitting beside, and they said, “Well, this should be easy because I took Con Law in college.” I talked to three or four more people that day who said they had had it already in college. I thought, “This is going to go terribly because I know less about this than anyone.” I guess it didn’t. I tell my law students about this and say, “It will be fine. You can think you know things and actually you don’t. And you can think you don’t know things, and that can actually make it easier to perceive and to grasp things.” It’s hard to predict up front who is going to see what. I wouldn’t assume anyone has a better grip of the world based on where they are coming from.

I’ve read so many different criticisms of the federal judiciary. Bearing in mind that I’m not a legal scholar, I don’t think I’ve ever seen anyone else make the case that these particular problems were built in. The assumption often seems to be that this was working in some grand and glorious ideal time in the American past, and then it all fell apart.

That’s the deep message of the book, although perhaps the title gets in the way. That is the more profound criticism that’s being levelled in the book.

Are there any other ideas with regard to this book and your other work that you want to leave LEX readers with?

I think it’s really important to think hard about the legacies that we have embodied in the law and not to take them at face value, not to take them as slogans, but to take them as things that require rethinking and revival every genera tion. That’s the project of the book with respect to judicial independence.

The next book is a short book about the rule of law. I would say the same things about the rule of law. The rule of law requires a certain revival under different circum stances every generation. ■

I’m in the odd position of writing a book that’s very critical in many ways of the federal judiciary and dedicating that book to the judge I clerked for who is still living.

LEX Infrastructures 19

The Law Is Too Important to Be Left to the Lawyers

The Return of the BA in Law

By Analisa Goodmann

Before a graduate degree became almost universally required to practice law in the United States, undergraduates once roamed the halls of the country’s law schools. The increase in jobs and job functions in areas adjacent to the law has encouraged some pioneering law schools to bring undergraduates back onto the law school campus.

Previous page: Alumni of Vanderbilt University Law School received JD degrees at a special investiture ceremony in October 1969.

A few months later, Perdue wrote a letter to Vanderbilt Law Dean John Wade, joking that “for the past couple of months I have … insisted to all of those employed by me that I be called Doctor.” Turning serious, he then congrat ulated Dean Wade on the success of the JD weekend, during which many graduates returned to collect their newly minted degrees.

Some of the dozens of his fellow alumni who had responded to the school’s invitation to the weekend were not as jubilant about their new degree as Perdue. In his letter to Wade declining the new degree, alumnus Miller Mainer, who practiced in Nashville, enclosed a check, noting “I just do not feel like sailing under false colors and if I didn’t earn a JD either as a law student or as a profes sional honor, due to my legal life, I just don’t feel I have any right to it.”

Vanderbilt Law School arrived at the plan to grant retroactive JD s only after years of consideration, which included surveying law schools across the country about their own degree practices. And, even then, in a letter sent in October 1969, Dean Wade addressed the new JD alumni as “Doctor” with quotes—perhaps suggesting some lin gering doubt. This range of mixed responses reflected the unsettled and variable nature of legal education in the United States throughout the 20th century.

In the early days of the nation, many attorneys were educated informally via apprenticeships with law firms, clerkships with judges and self-study. In 1792, the College of William and Mary in Virginia issued the first law degree in the United States, a Bachelor of Law degree. In the 1840s, the LLB (for Legum Baccalaureus) came into vogue, and for the next several decades, formalized legal education was at the undergraduate level, although obtaining a degree was not necessarily the preferred path for would-be lawyers.

After the Civil War, an effort arose to improve formal legal education, but institutions had trouble attracting students because they were the more costly option, and no standardized requirements compelling students to undertake formal study existed. Around this time, the law industry was expanding significantly, gaining tens of thousands of lawyers between 1850 and 1880. Perhaps in reaction to this expansion, there was a push for a more formalized vetting system. By 1890, admission to the bar in the majority of jurisdictions in the U.S. required some formal education or apprenticeship.

One Friday in October 1969, Doran E. Perdue returned to his alma mater, Vanderbilt University Law School, to receive his Doctor of Jurisprudence degree. An already-practicing attorney from Evansville, Ind., Doran was one of dozens of Vanderbilt alumni to retroactively receive a juris doctor (JD) degree to supplement the Bachelor of Laws (LLB) degrees that they already held.

The Return of the BA in Law22

Harvard Law School became the key player in creating the three-year curriculum that was the precursor to what law schools offer today. By 1871, Harvard expanded the length of its LLB program from 18 months to two years, ulti mately adopting a three-year version in 1899. The program remained, nominally at least, an undergraduate one, but by the beginning of the 20th century, the more prestigious law schools were mostly admitting students who already had college degrees.

The first law degree remained formally an undergrad uate one, leading many students to receive a bachelor’s degree and an LLB . This contrasted with the degree con ventions for other professions—in medicine, for example, students received graduate degrees. By the turn of the cen tury, law students began asking for graduate law degrees. In 1902, Harvard law students petitioned the school to offer a JD degree, which according to lawyer and author David Perry, was based on the juris utriusque doctor degree offered at some European universities.

Although the effort to formally transform law school to a solely graduate institution initially failed at Harvard, it succeeded elsewhere. In 1902, the University of Chicago Law School was established as a graduate institution, requiring a college degree for admission and awarding JDs to its graduates. But in another complicated twist, Chicago eventually partially reversed course and agreed to admit students who had not graduated from college, conferring on them the LLB , offering JD and LLB students the identi cal curriculum. Other law schools followed Chicago, award ing both degrees. Interestingly, however, even though Harvard Law School began requiring a college degree for admission in 1909, it still did not offer the JD. In fact, the resistance of Harvard, Yale and Columbia to offering the JD prompted several other schools to revert back to offering the LLB , although some awarded JDs as an honor to excep tional LLB students.

Throughout the next several decades, legal education slowly standardized. As early as 1921, the American Bar Association (ABA ) and the American Association of Law Schools (AALS ) began issuing recommendations on the level of undergraduate education students should have achieved before being admitted to law school. Between the 1920s and the early 1970s, the ABA’s review of legal education reports included a close tracking of which American—and occasionally Canadian—law schools

This page details the plan to confer degrees in law at the College of William and Mary, where the first law degree in the United States was awarded in 1792.

required undergraduate education and how much. By 1971, the majority of ABA-approved law schools required three years of college or an undergraduate degree. And the graduate degree eventually became de rigueur at law schools across the country after Harvard’s faculty voted in 1969 to begin awarding JD s and to retroactively grant that degree to alumni who held LLB s if they wanted one.

The Undergraduates Return

As the legal profession and legal education became more formalized over time, American law also became, and con tinues to become, increasingly complex. For example, new laws—and with them, new legal sectors—have arisen as a result of the invention of new technologies, the growth of new industries, the expansion of civil rights and the rise of globalization, along with the slew of issues that accom pany it. This increasing complexity has also resulted in the creation of, and increasing demand for, legal roles for non-attorneys. This phenomenon is perhaps most evident in the regulation and compliance sectors across multiple fields, such as health care. (The United States Bureau of Labor Statistics projects 6.2 percent employment growth for compliance officers between 2020 and 2030.)

The expansion of law-adjacent careers occurred prior to and in the wake of the economic crash in 2008, which had

In the early days of the nation, many attorneys were educated informally via apprenticeships with law firms, clerkships with judges and self-study.

LEX Infrastructures 23

Undergraduate students gather between classes outside Drexel University’s Korman Center.

a knock-on effect of decreasing the number of applications to JD programs at law schools throughout the United States. As a result, legal educators were faced with a conundrum: increasingly complex law, an ever-growing demand for a new type of legal professional and decreased demand for traditional graduate legal education. For the past several years, universities have responded to this problem by cre ating professional degree programs, often at the graduate level, that offer students training in the legal expertise needed in these expanding sectors. (Kline Law’s Master of Legal Studies program is one example.) And two law schools, the University of Arizona and the University of Buffalo, took the significant step of creating similar programs for under graduates, bringing college students back to the law school, by creating Bachelor of Arts (BA) in law programs.

Marc L. Miller is dean of the University of Arizona James E. Rogers College of Law.

The University of Arizona’s James E. Rogers College of Law partnered with the university’s College of Social and Behavioral Sciences and the School of Government and Public Policy to become the first institution in the United States to confer a BA in law, which is offered in person and

online. According to Arizona Law Dean Marc Miller, the program was created in response to a long-standing con versation at the College of Law about how to increase access to legal education as well as access to legal services by those trained in law, and with the knowledge that other countries offer undergraduate degrees in law. Achieving greater stu dent diversity was also a goal. The undergraduate popula tion, Miller pointed out, was typically more diverse in many ways than the JD population.

Although Arizona’s BA in law is still new, the school points to strong indications that it is achieving its goals.

“The BA in law program has been much more representa tive of the general population than have traditional JD pro grams,” said Keith Swisher, a professor of Legal Ethics who also directs the BA in law and the Master of Legal Studies Programs. “Racial and ethnic diversity has been greater in the BA in law program than in traditional JD programs; the number of first-generation college students has been higher on average,” he continued.

“This is sort of my motto: Law is too important to be left to the lawyers.”

Students who wish to matriculate to Arizona’s BA in law program apply to the university, not the law school. They are required to take general education classes at the university, and the major-specific courses mimic those of the first year of law school, although the BA and JD classes are usually taught separately, according to Swisher. Law students at both the BA and JD levels do collaborate on some of the journals the school publishes, however, and JD fellows work with undergraduate students in a role similar to teaching assistants.

In 2015, Arizona Law began offering the BA in law abroad by launching a dual-degree program with the Ocean University of China in Qingdao, China. “One of our greatest potential exports is American private law,” said Miller. “Most of these students are not coming to the U.S. to get a JD or LLM , although many do. The value is in learn ing U.S. law, then going to work with Chinese government agencies or companies.” Graduates guide their organiza tions on what U.S. laws come into play as the organization operates in the American market, he explained.

Currently, 1,000 students in the American versions of the Arizona program are enrolled in the in-person and online BA program, and 700 students have graduated. Among the 2021 graduates, two thirds report that they are pursuing jobs in legal services, with the next highest sectors being finance and human resources, according to Swisher. One-third of graduates report going to law school or planning to do so.

Recent graduates affirm the degree’s value in the work place. “I always encourage people to get that legal founda tion and education,” said Lauren Easter, who graduated from Arizona with the BA in law in 2020. “I’ve seen it over and over again: Employers really love candidates that have some type of legal background.”

Arizona Law launched a dualdegree BA in law program with the Ocean University of China in Quingdao in 2015, with the first class graduat ing in June 2019.

James G. Milles is vice dean for undergraduate studies at the University of Buffalo School of Law.

Democratizing Legal Education

The BA in law does more than just equip graduates to compete for careers in an increasingly globalized world. According to some of its proponents, it also better prepares graduates to participate actively in American democracy.

James G. Milles, the vice dean for undergraduate studies at the University of Buffalo School of Law, was skeptical about the BA in law when conversations about creating such a program at the university first began. But by the time the program launched in 2019, his skepticism had turned to faith. “I really believe in this program,” he said. “It is important in building democracy. I think there’s a need for that…. We’ve seen it for the last several years. There’s a need for people to understand the role of law in a democracy, and there’s not a lot of understanding out there…. This is sort of my motto: Law is too important to be left to the lawyers.”

Milles cites the increasing complexity of the law as well as the distance between the law and “ordinary people’s

LEX Infrastructures 25

Rose Corrigan is associate dean for undergraduate education at Kline Law.

Drexel University opened in 1891 as the Drexel Institute. The original struc ture is known today as the Main Building.

experience” as one of the drivers behind the creation of the BA . A goal of the program, he said, is to foster individ uals who “aren’t going to be lawyers but they’re going to be working in positions where they’re going to be talking to lawyers and working with [them].”

As of early 2022, 200 students are enrolled in the UB School of Law undergraduate major, and the school is working to integrate the undergraduate and JD com munities, with JD students acting as teaching assistants and BA students supporting work in clinics. Buffalo’s program is similar to Arizona’s in that students apply to and are admitted by the university. Two tenured law school faculty teach in the program, and adjuncts and full-time lecturers cover the rest of the courses. Several

alumni teach in the program as well, which Milles says, they greatly enjoy.

Professor Rose Corrigan, associate dean for under graduate education at Drexel University’s Kline School of Law, said that she sees the move toward educating undergraduates in law as “democratizing legal education.” Corrigan has been central in leading this effort at Kline Law, where a brand new undergraduate minor in law was launched in 2022.

“For a long time, law was the province of powerful, priv ileged people,” said Corrigan. “But law is a discipline that touches people’s lives in so many different and important ways. I very much believe that undergraduate education in law can be really critical, really powerful.”

Daniel Filler, Kline’s dean, agrees. He envisions the school producing graduates at every level who will become active participants in democracy, whether they practice law as attorneys, work in law-adjacent fields or pursue careers less directly related to the law.

“An element of our democracy is engaged, civically minded and civically educated citizens,” said Filler. “My theory is that law is performed, followed and enforced formally and informally—norms, for example, are part of the informal enforcement—by a citizenry that believes in law. And so, my thinking is that our undergraduate degree, and, in fact, our whole law school program, is designed to be an educational infrastructure in support of this notion of the rule of law.”

The Return of the BA in Law26

The BA Comes to Kline

This fall, Kline Law will become the third law school in the United States to offer a bachelor’s degree in law, and the first at a private institution. In addition to fulfilling Drexel University’s undergraduate core course requirements, stu dents admitted to the program will take such Kline courses as “Law and Society,” “American Legal Systems” and “Legal Reasoning.”

“The undergraduate law program,” said Corrigan, “is structured in such a way as to encourage students to think big, to see connections between, say, legal and political systems or legal and economic systems. At the same time, the program will give students more training in law than they would typically get in undergraduate classes.”

“We are aiming,” she continued, “to find that sweet spot of teaching about law and legal rules situated within a broader societal context.”

The new BA in law will build on the school’s existing minor in law program. Kirill Sosonkin, BSBA ’23, a junior majoring in finance and minoring in law, praises the pro gram’s pedagogical approach. Corrigan’s “Law and Society” course, he said, taught him to think for himself.

“Instead of just learning material and writing about it,” he explained, “Professor Corrigan’s class included review ing case studies that presented different perspectives on the same material, and then students made their own deci sions on how they felt about the cases.”

The final class project, which was a debate on whether a hypothetical defendant should receive the death penalty,

underscored for Sosonkin that different individuals can interpret the same material in significantly varied ways. He found himself and another student on opposing sides of this question. “We discovered in the debate,” he said, “that the difference in our opinions was the result of how we were interpreting one sentence in the hypothetical.”