Paris

Mexico

Mexico

Cambodia / Italy / California / Nepal

- Enhance your wellbeing upcountry at Koele

THE ORIGINAL BAG

Create one aesthetic statement.

Gaggenau appliances: individually accomplished, exceptional together

It takes a different kind of energy to start something powerful. Introducing the new Continental GTC Speed. We’re starting something powerful, and so is Dossier. Congrats on your launch issue.

This is the second “first” issue of Dossier. The first time it launched was a long time ago — I was still in my 20s, as was most of our team. The magazine was originally conceived of as a creative endeavor providing contributors with a “white space” in which to share their expressions of the world. Its core tenet was to give equal weight to all forms of creative expression. Its first issues were put together on my kitchen counter. But Dossier outperformed its humble origins, growing beyond a print magazine to include a daily website and even a brick-and-mortar store. Despite these successes, after eight years, we closed the publication. We didn’t have the necessary foundations in place to grow it into a sustainable business.

Many of the team members and contributors who created Dossier remained my closest collaborators; several joined me when I was brought on to lead the 2020 relaunch of Departures as editor-in-chief. As an avid, lifelong traveler, I found moving into the world of global storytelling to be a revelation: travel is an endlessly wide tent that organically touches all aspects of culture. When the news of Departures’ closing reached us in mid-2023, our team’s immediate reaction was that we wanted to continue the work we had been doing, together. It didn’t take long for my business partner, Erin Dixon, and I to decide that the time was ripe to bring Dossier back from hibernation, working, as always, alongside Alex Wiederin.

In this new incarnation, Dossier will continue to draw on the creative friction that originally earned it critical acclaim. However, its aperture has widened to that of a luxury travel and culture publication that looks at the whole world. Dossier’s focus was always on culture at large, so placing travel at its center is a natural evolution. Tourism, at its best, is an industry with an enormous potential to enact positive change, and a pillar of our team’s work has been to seek out and shine light on those businesses and people who are worth talking about, thinking about, and promoting — we will continue doing that here.

I recently heard a line that really stuck with me: Luxury sits at the intersection of art and commerce. In its previous incarnation, Dossier was focused entirely on art. It was young, as were we, with idealistic notions about art and commerce being mutually exclusive. We have matured since then, and Dossier, in this new iteration, has as well. The best things are not always brand new; sometimes classics are classic for a reason.

–Skye Parrott, editor-in-chief

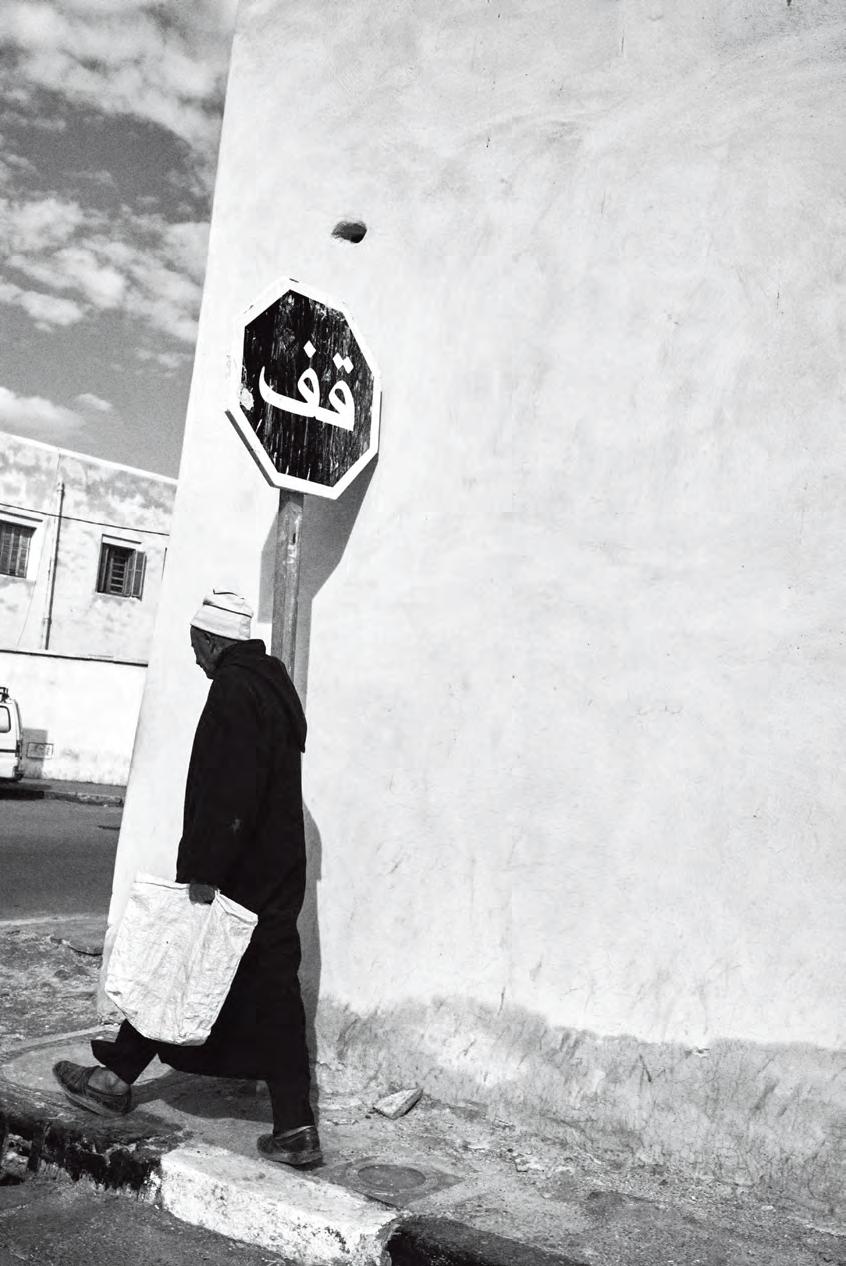

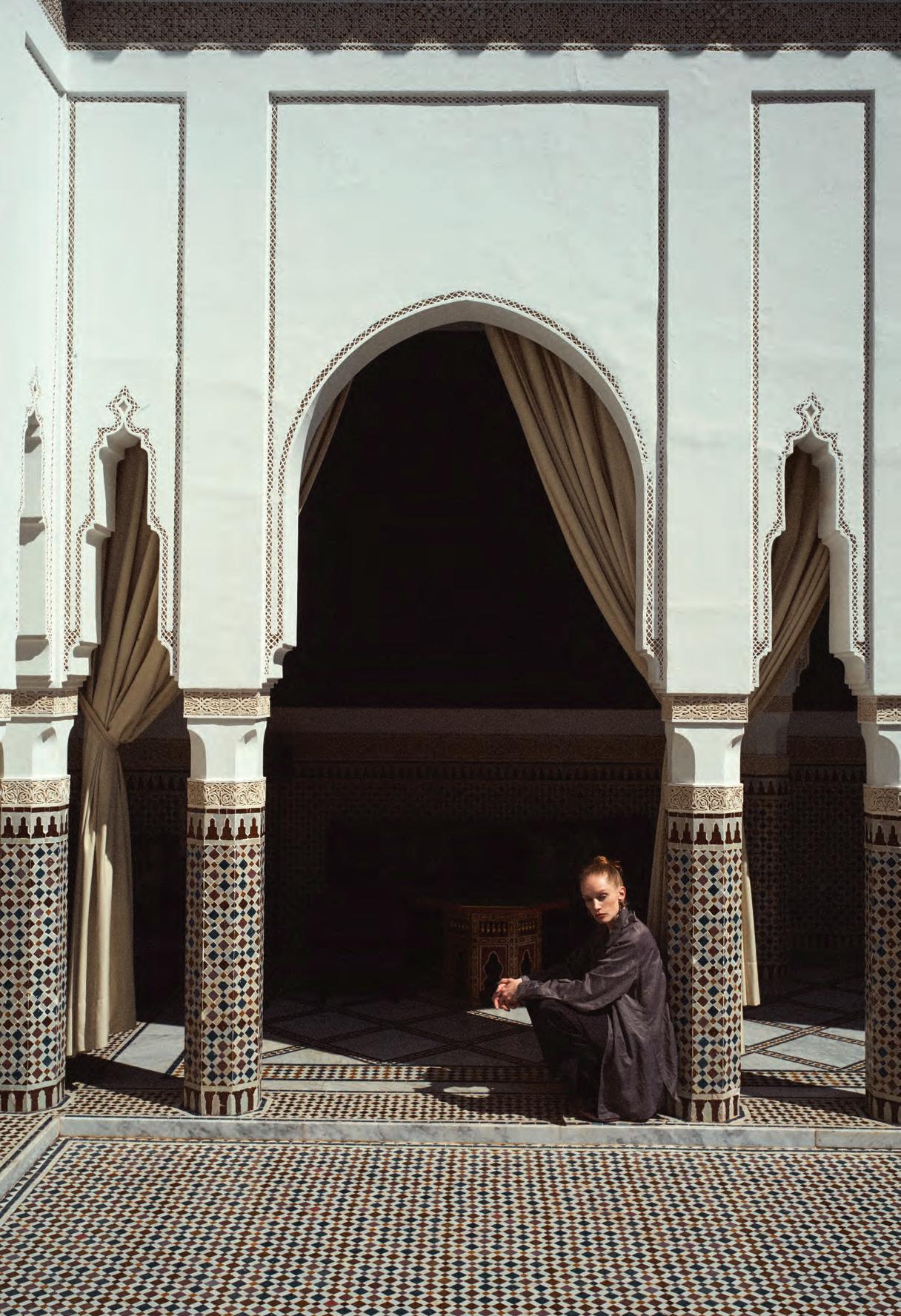

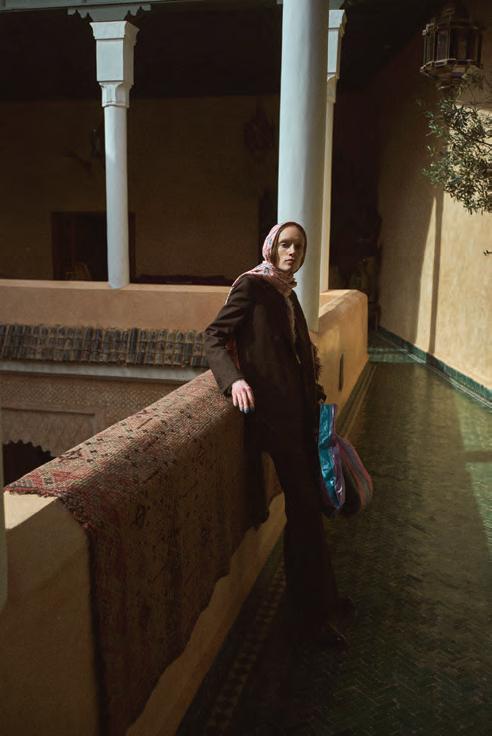

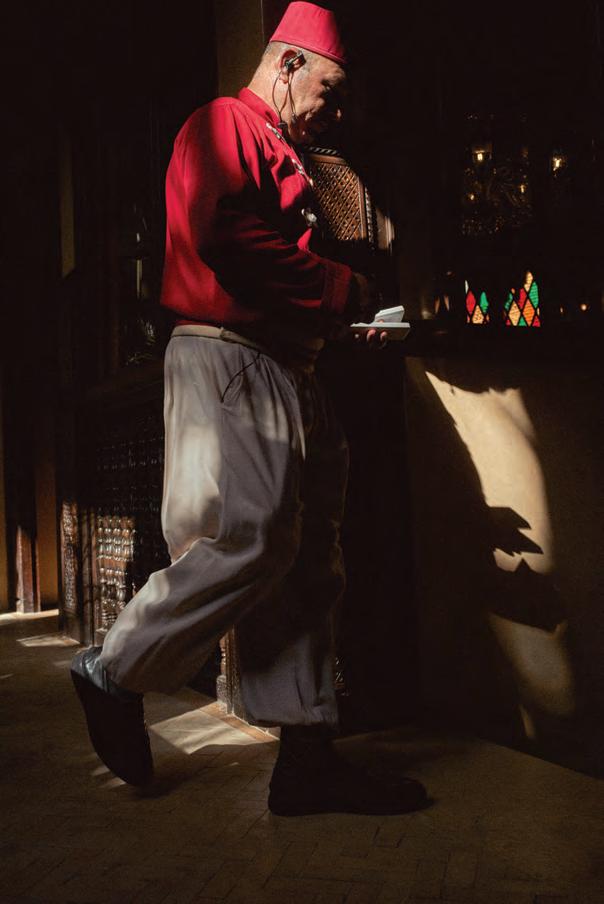

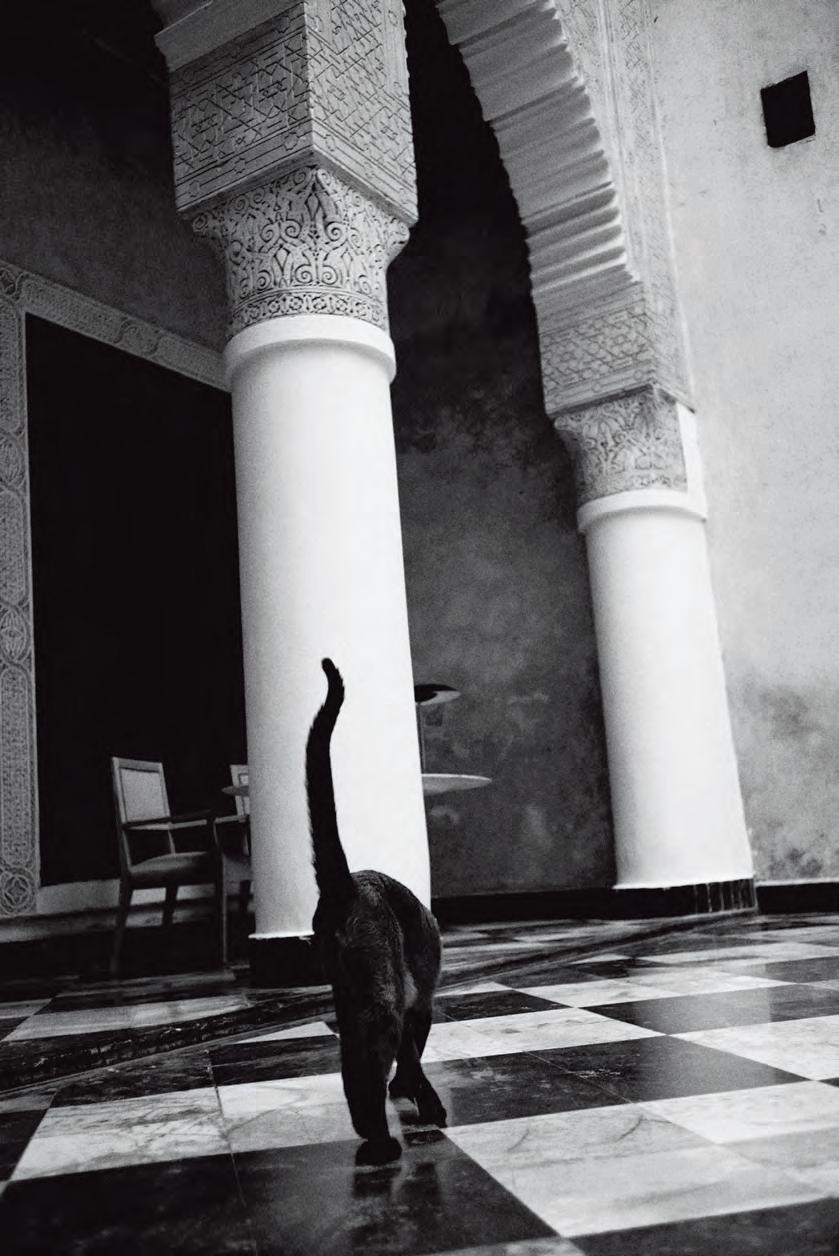

A Song at Dawn: Wander through the winding souks, vibrant streets, and exceptional hotels that have inspired prose and drawn people to Marrakesh for generations.

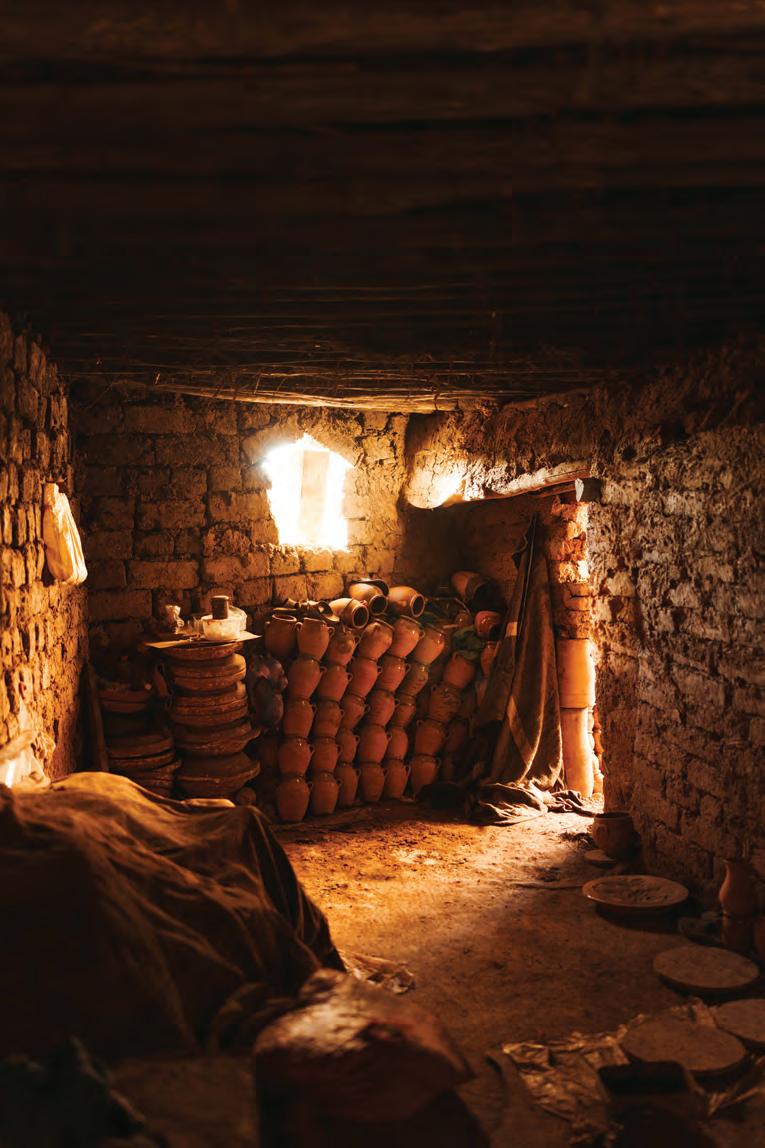

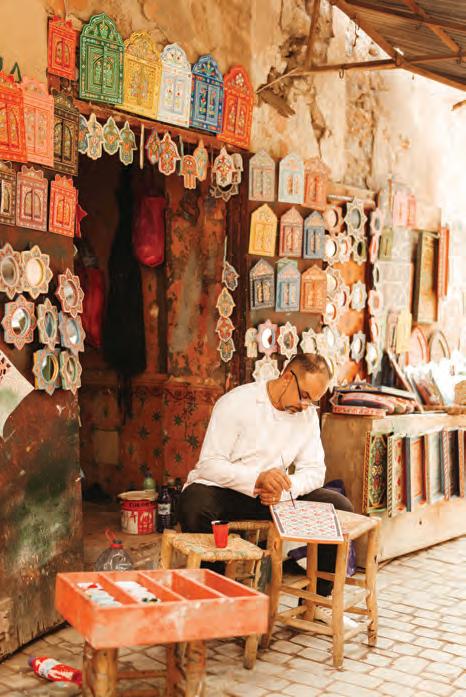

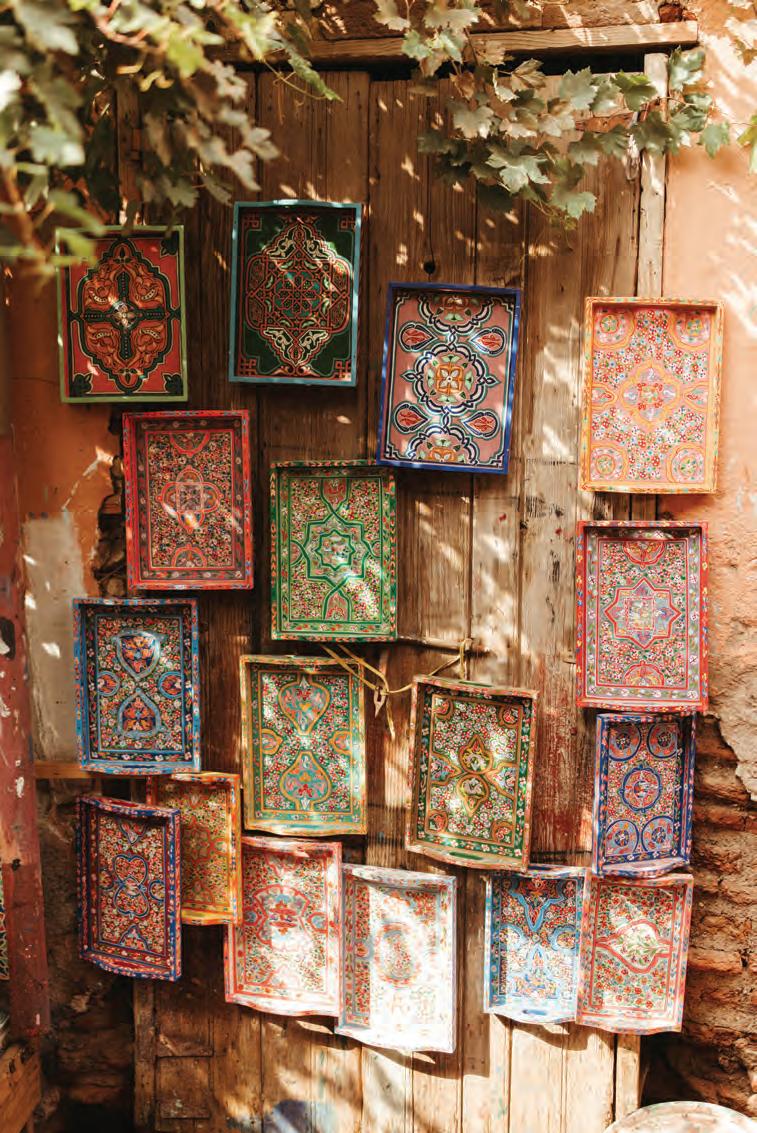

In the Medina: In a time of transition, Marrakesh’s craftspeople embody the international city’s history and future. Their artistry is not just a livelihood; it’s a commitment to preserving their cultural heritage.

Greater Expectations: Skye Parrott takes on the challenge of trying to understand what we talk about when we talk about sustainable travel.

Something Like Magic: Reflections from Sayulita, Mexico: as it was, how it is, and the people who make the place.

A Rite of Passage: Christopher Bollen reflects upon what it means to wear a good suit as he steps into a custom-tailored one from Gucci.

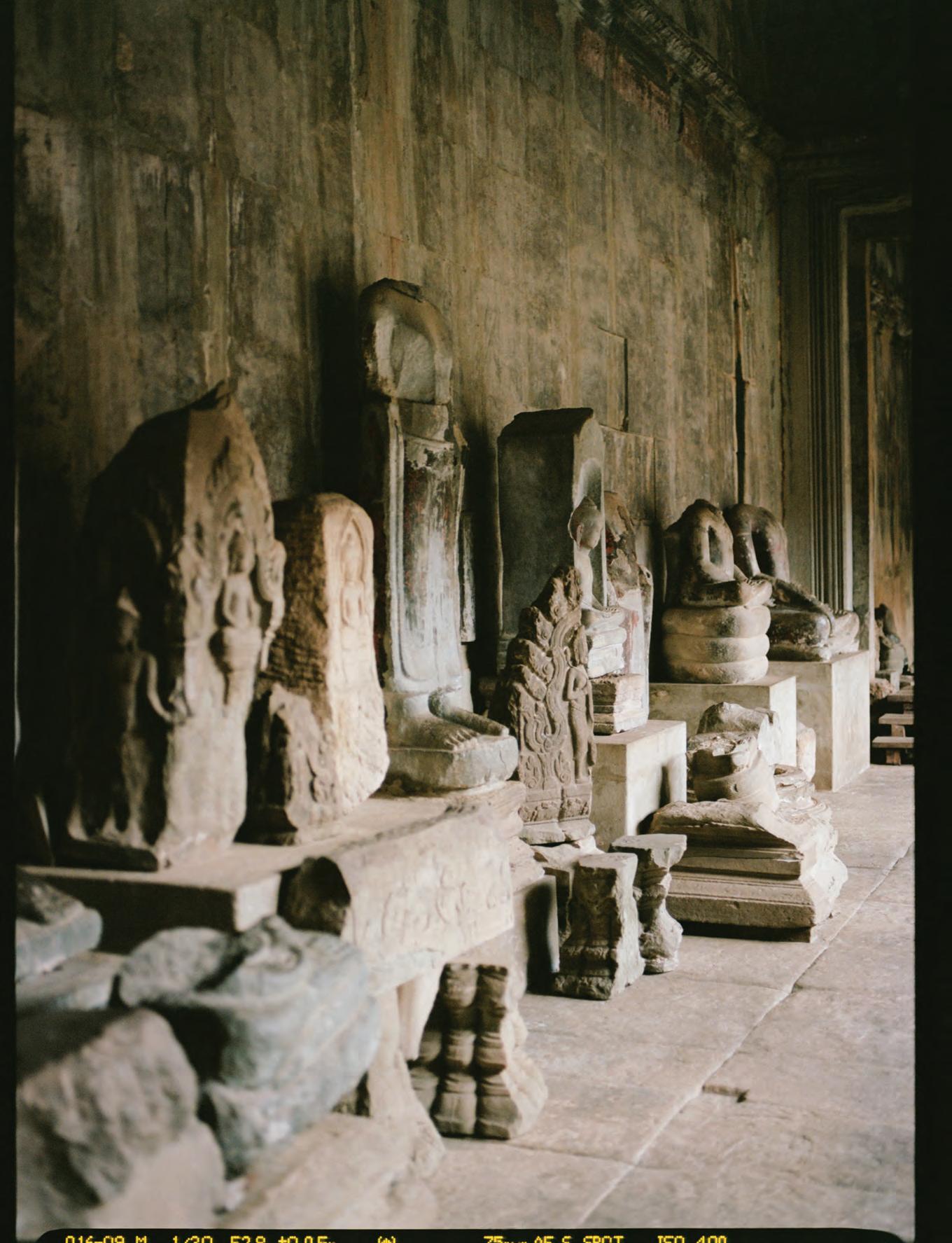

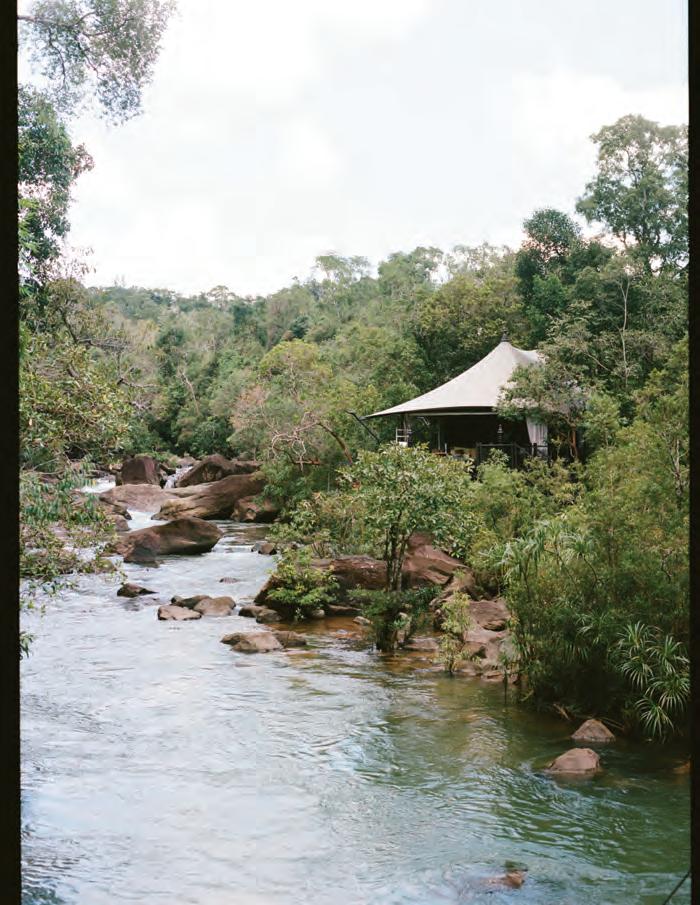

The Bigger Picture: A transformative trip to Cambodia introduces radical ideas of luxury and its potential to do good.

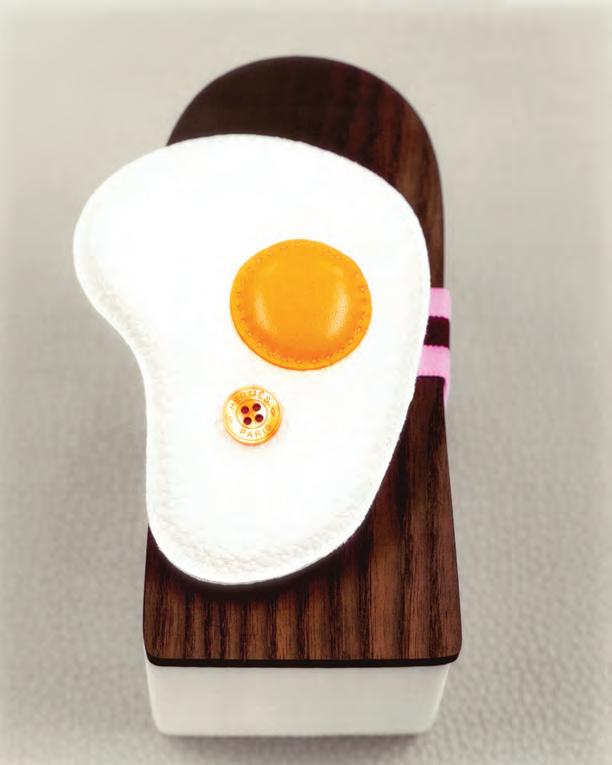

Object Lesson: At Hermès petit h, the legacy French house’s experimental atelier, magical thinking reconstitutes would-be waste into mind-bending wonders.

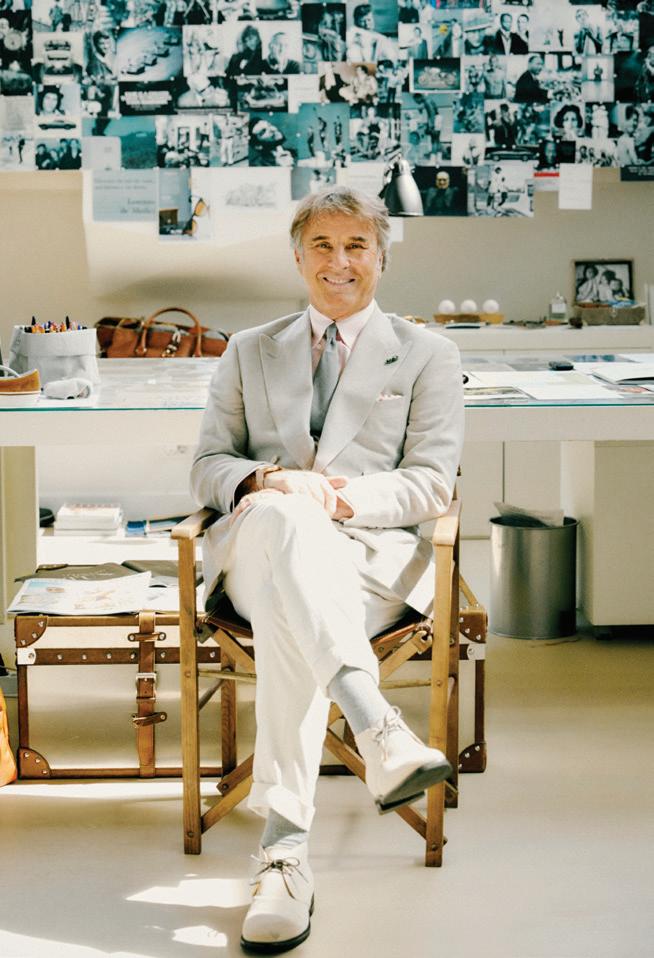

Coming of an Age: Brunello Cucinelli expounds on the winds of change blowing through our turbulent world and their potential to precipitate a brighter future.

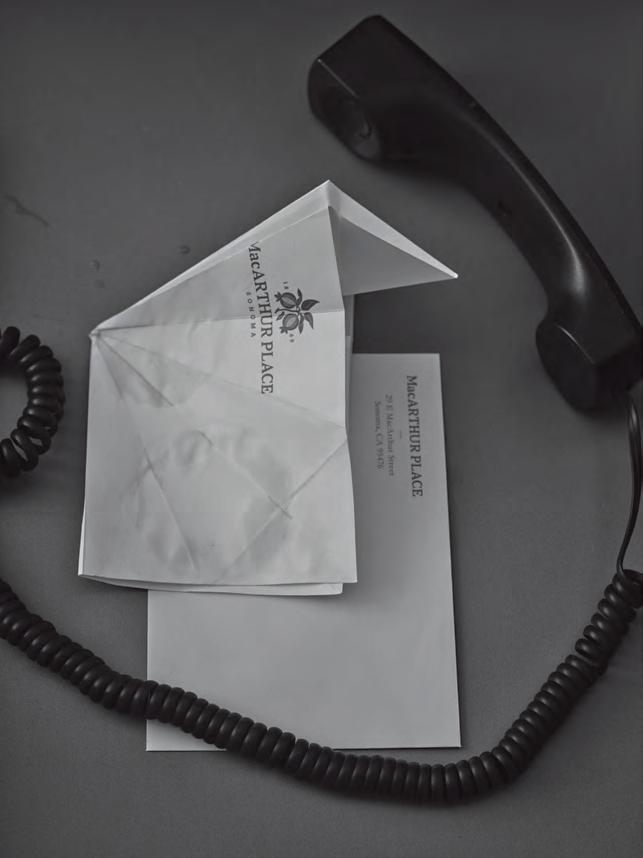

Wherever We Go: An ode to not-so-humble hotel stationery — its multifacted personality and purpose, and the imaginative places it takes us.

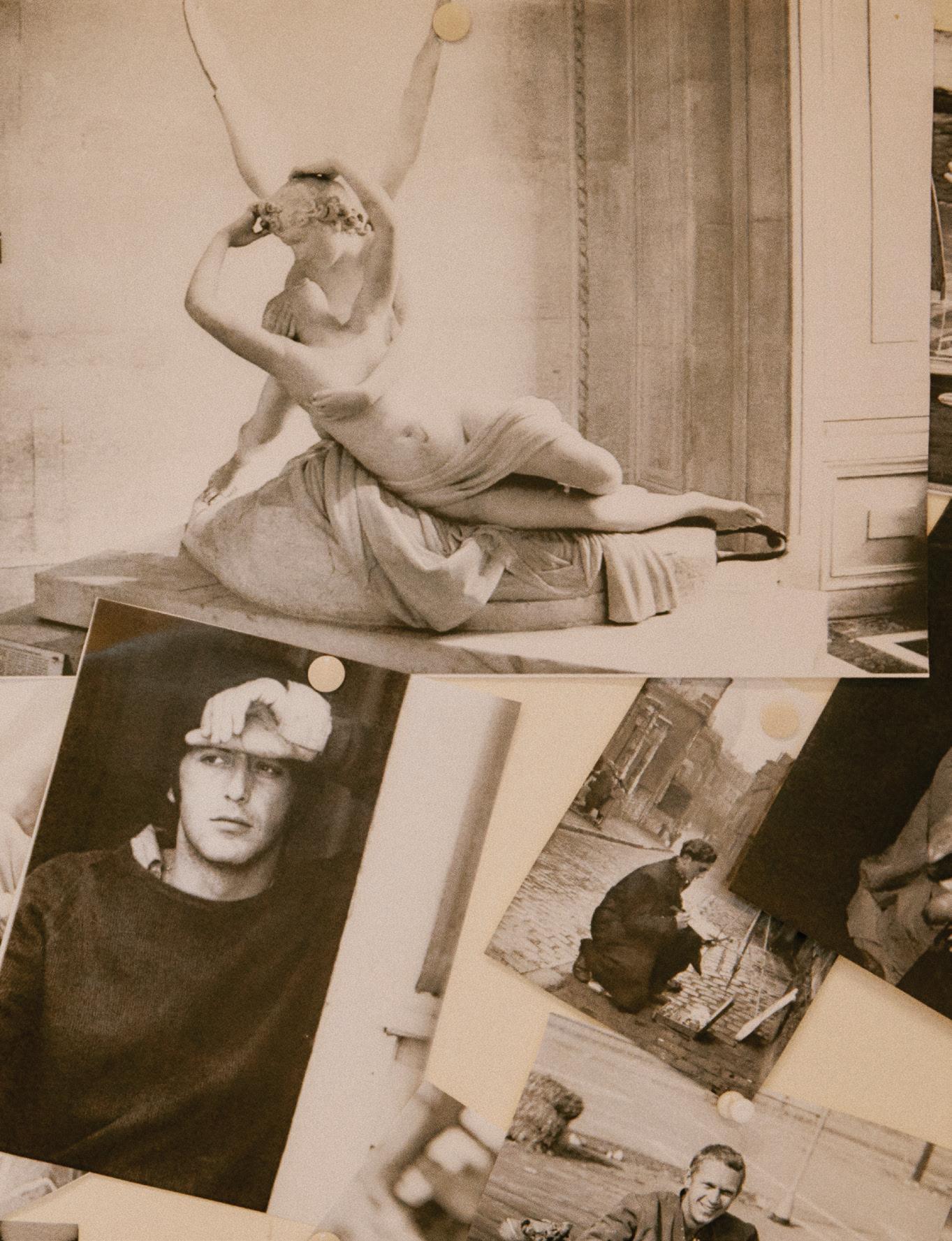

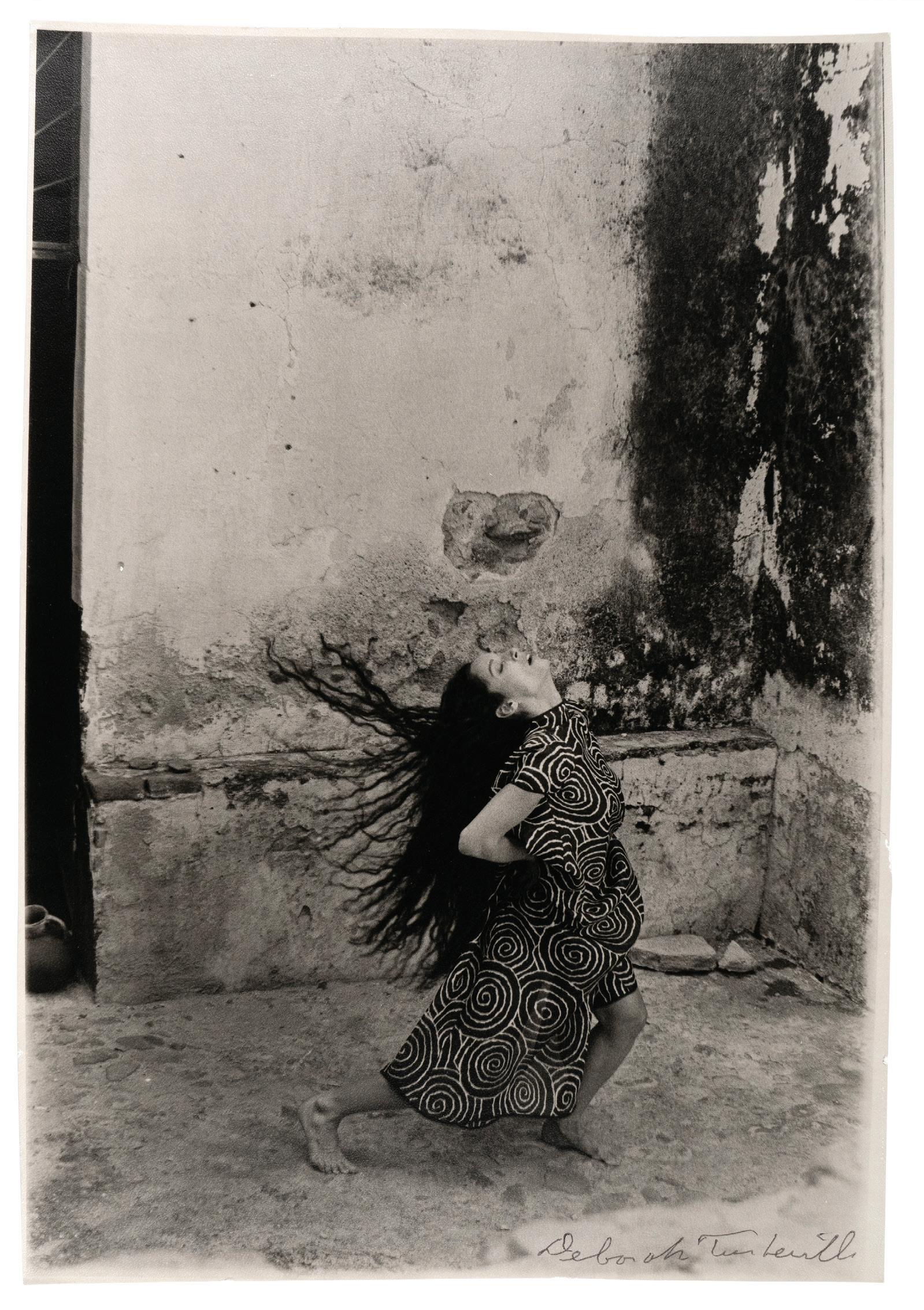

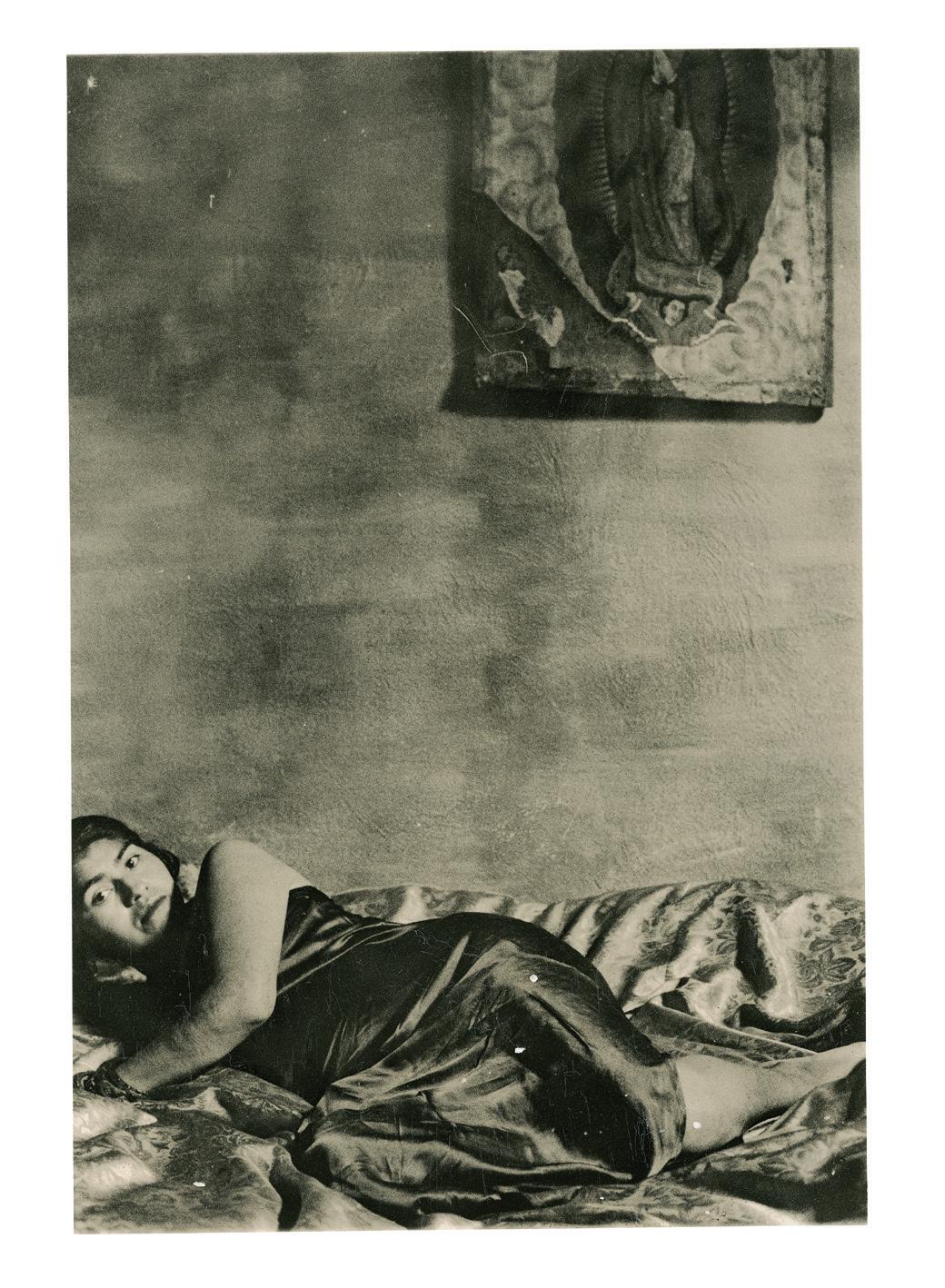

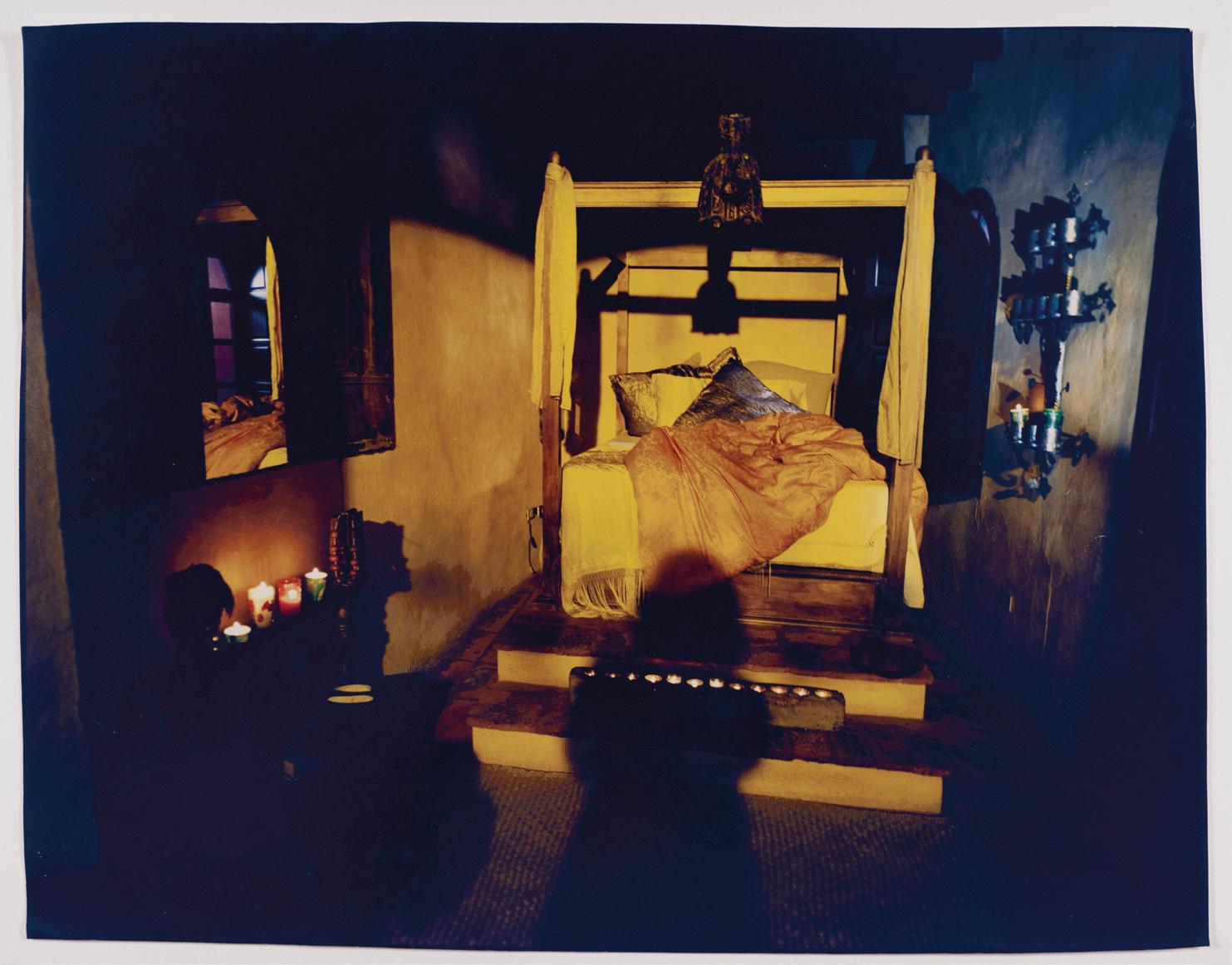

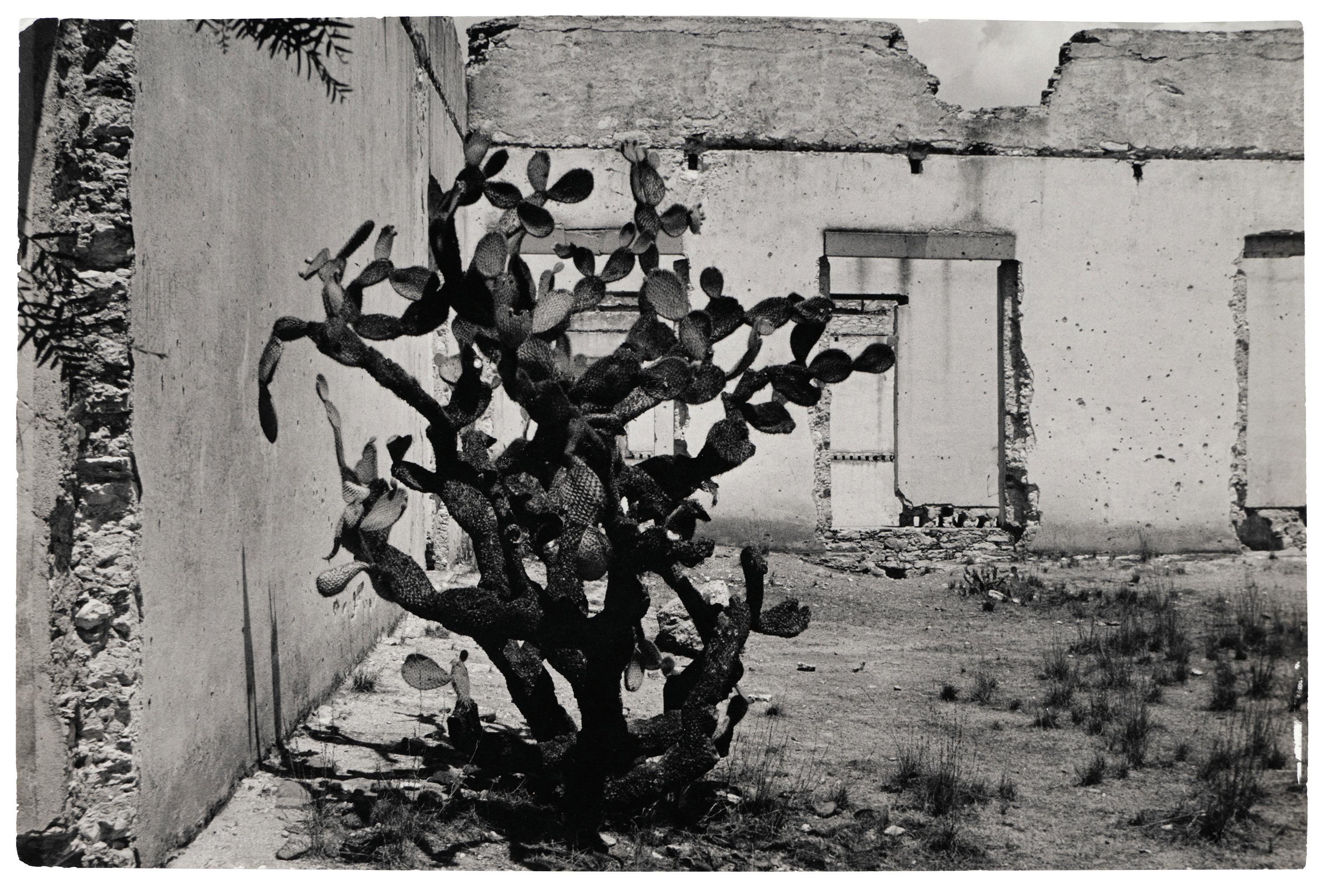

Beautiful Rebellion: Deborah Turbeville’s photographs of Mexico, which epitomize the artist’s line-blurring version of reality, finally get their due in a new Louis Vuitton Fashion Eye album.

Genesis: Juan Brenner’s new photobook captures the intersection of history, culture, legacy, and potential that characterizes the Guatemalan Highlands and its young generation’s exchange with the world.

The Dossier: A collection of thoughts, ideas, recommendations, and discoveries from all over the globe.

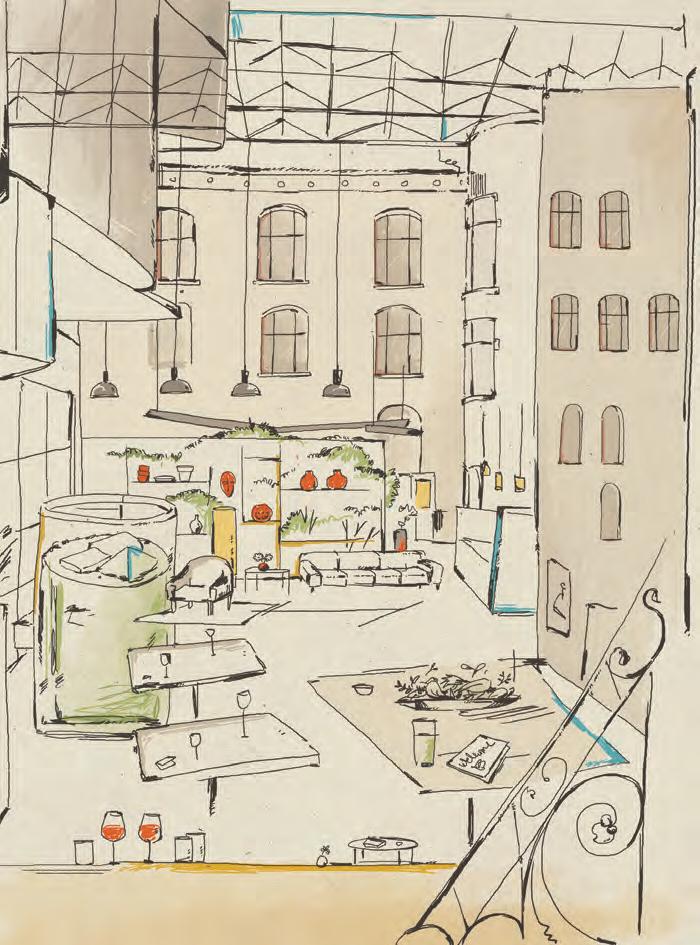

Capital Escapes: From Paris to Rome to Amsterdam, these hotels are distinct, characterful oases that embrace their destination’s history while celebrating the best of today.

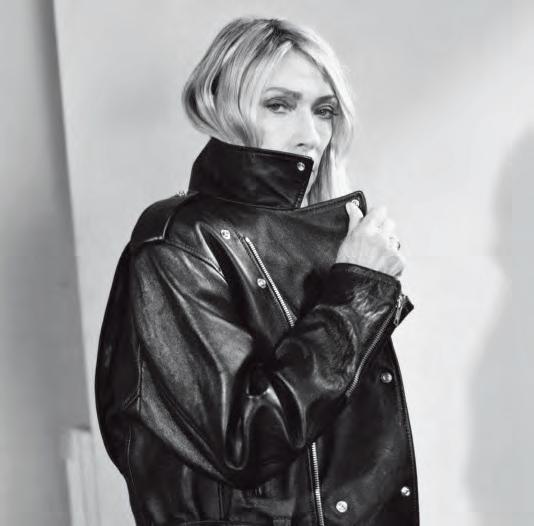

Novel Ideas: Musician, artist, and alt-rock icon

Kim Gordon goes deep on the books that have informed her life and work.

Super Natural: Czinger Vehicles and its founders are shaping the future of the automotive industry — and it looks a lot like nature.

What Lies Beneath: From wildly conceptual to peculiarly orthodox, there’s always more to Claire Choisne’s Boucheron designs than meets the eye. Memories of the Living: Artist Jammie Holmes creates visual poetry that uplifts his subjects in and beyond the moment.

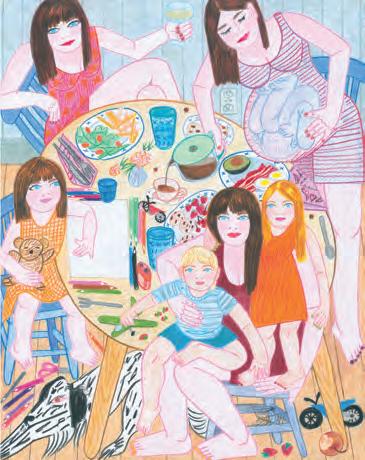

It’s That Simple: Chef Mina Stone and artist Madeline Donahue discuss the everyday art of the holiday table.

Taking Root: Combining oldworld plant breeding with modern sensibilities, chef Dan Barber’s new class of produce is nutrition-packed and incredibly delicious.

A Place Apart: Writer and cook Colu Henry finds fresh inspiration for her forthcoming book on Nova Scotia’s North Shore.

Field Notes: LaTonya Yvette shares an exclusive excerpt from her book Stand in My Window: Meditations on Home and How We Make it

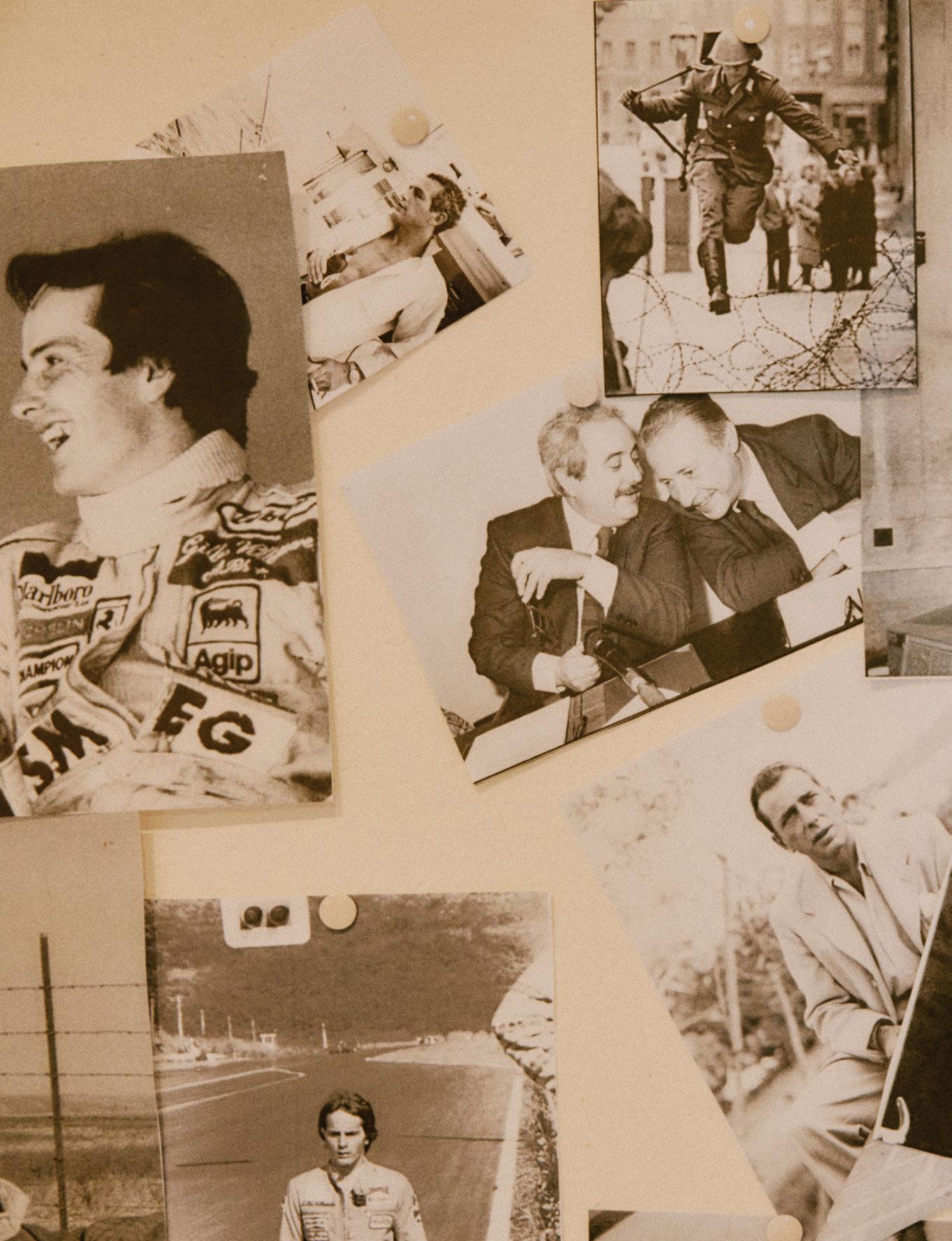

Survival of the Fittest: When examined through a present-day lens, the 24 Hours of Le Mans reveals lessons for life as well as the track.

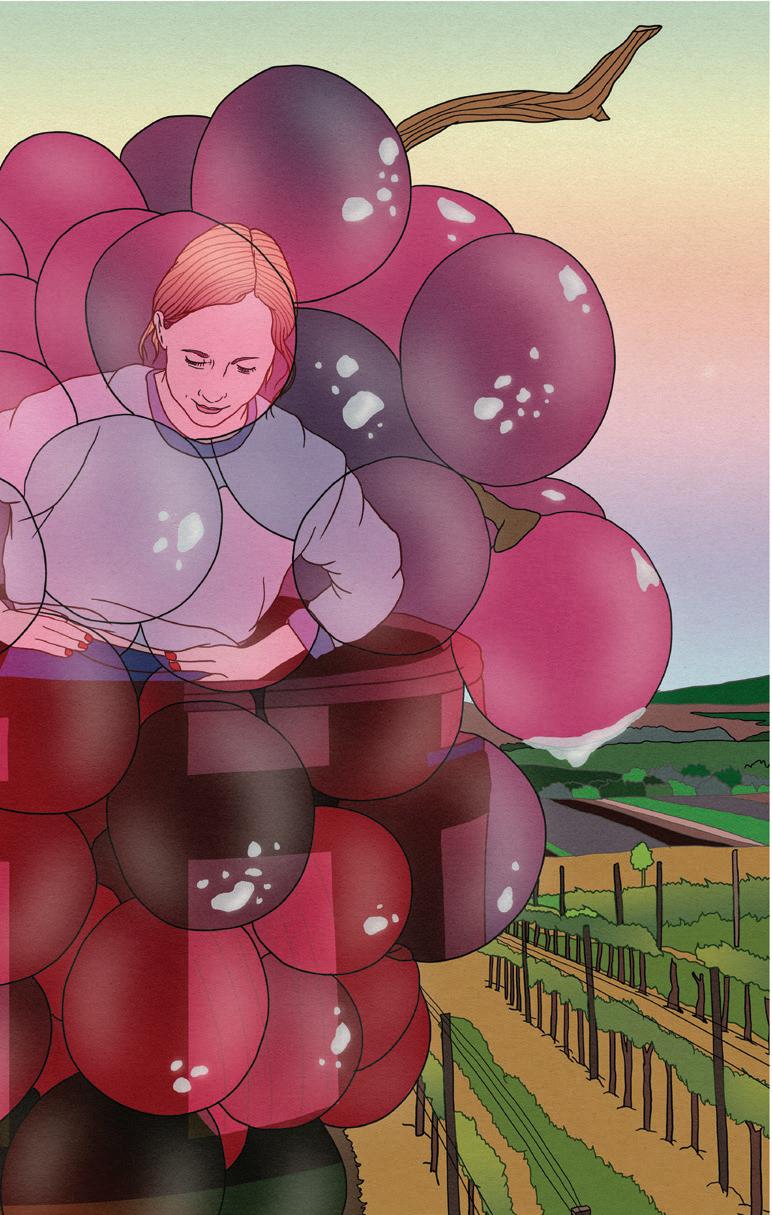

Between the Vines: A journey through three grape harvests exposes the fruit’s power to uncover hidden truths, long before it’s turned into wine.

On the Delta An intergenerational road trip through the Deep South conjures local and familial legends.

What’s Mine is Ours

At Dwarika’s Hotel in Kathmandu, a personal mission to save a piece of history becomes an inspiring preservation story.

Sought and Found: From evocative scents to objects with a clear provenance to classics that get better with age, these are among our favorites.

A collection of eight gift boxes and certificates

Picture yourself relaxing among fragrant dunes on the edge of the ocean, wandering through delightful gardens infused with the scent of eucalyptus or gazing up at the pure azure of a clear blue sky–all inspiring moments that channel that almost indescribable feeling of being on holiday. Relais & Châteaux offers a range of gift certificates and boxes. Each gift box is an invitation to escape, offering experiences and stays for two people in properties that reflect the architectural and cultural diversity of Relais & Châteaux.

You find yourself perpetually drawn to the land of treasures that is Greece. Whether it’s Santorini’s colorful cli s or monuments of the Acropolis, there’s always another stretch of coast, ancient city, exquisite cuisine or superb winery that beckons. And it’s best experienced aboard The World’s Most Luxurious Fleet®

THE MOST INCLUSIVE LUXURY EXPERIENCE® TO LEARN MORE VISIT RSSC.COM CALL 1.855.573.1973 OR CONTACT YOUR TRAVEL ADVISOR

Christopher Bollen writer, A Rite of Passage

It took place in 1987, the summer between fifth and sixth grades. It was my first time out of the country and I went with my family to England and France. Unfortunately, this big trip also happened to coincide with the summer we were getting our first dog, delivered upon our return. So for two weeks, breezing through the English countryside and touring Mont Saint-Michele, I hoarded all of my film, refusing to take more than a dozen photos, to save it for the arrival of said puppy. Despite one major life moment overshadowing another, I do remember the excitement of the awayness, all the strangeness and newness of being in a foreign land that later, long after the dog was gone, would become an adult addiction.

My first significant trip was at 19 to Nepal. I had just come out of college and had no idea what my future would look like. During my time there, I lived

and worked with children in a small village close to the border with India. In the town, I met a Chinese writer called Valerie, who was struggling to finish a book on Buddhism. She told me, astonished and somewhat deceived, that after years trying to define the being, she had found that there was nothing to be defined. There’s only emptiness, and we are just one with this evolving world. Still today, almost 15 years later, I think about Valerie’s discovery.

Anne Menke photographer, Something Like Magic

In 1999, I spent two weeks at 5,000 meters with the Quechua people in the Andes Mountains of Peru, learning a lot about the importance of enjoying the process of living. The Quechua people are incredible and gentle. I remember their children herding llamas, with a smile on their faces all day long. When I returned to New York from this experience, it took me more than three days to reorient myself to my lifestyle, but the gift of living in the moment and taking in the magic of our beautiful planet remained with me.

Laura Smith writer, A Place Apart

This photo was taken in Myanmar in 2012. I’d traveled as a kid, but this was my first big travel experience as an adult,

and it forever changed my approach to new places. I was 26 and had no idea what I was doing. Myanmar had just “opened up” to tourists, so there was almost no tourism infrastructure and very little access to the internet. On a whim, I picked up the democracy activist Aung San Suu Kyi’s biography at an English language bookstore in Bangkok the day before I left. What a mistake it would have been to go without that context! It added layers of meaning to everything I experienced and challenged my beliefs about what it means to be an ethical tourist. Now I try to read deeply about places before I travel. Novels can be a beautiful way into a faraway place, too.

Nazih photographer,

My first trip to the United Arab Emirates, specifically to Dubai, marked my first adventure abroad. Although it was still within the Arab world, I was struck by the subtle yet distinct differences in culture, language, and even the facial features of people who, in many ways, felt familiar. Dubai’s opulence — the luxurious hotels, towering skyscrapers, and sheer scale of everything — was awe-inspiring, especially for someone coming from an emerging North African country. The experience was transformative and it ignited a love for travel that has only grown stronger. From that moment on, the thrill of stepping onto a plane and into a new world became addictive. Since then, I’ve explored more of the Middle East, neighboring countries, the United States, and beyond. And my journey is far from over.

Tell us about your first big trip and what it taught you.

Jess

Rotter illustrator, Between the Vines

One of my first big trips as a child was to none other than Walt Disney World in Orlando, Florida. It really was pure magic at every turn for someone obsessed with the characters, films, and music of that universe. At the time, I believed Goofy and I were married and loved to share that information with anyone who would listen. After being gifted a huge stuffed Goofy, I sat riding on the monorail back to the ’70s-looking Contemporary Resort with my husband and told my parents with a sonorous voice: Now everyone back at home will believe me.

Khira Jordan writer, Object Lesson

This is a (silly) photo of me inside St. Peter’s Basilica in the Vatican, taken by an Argentinian designer who was simi-

larly wandering around, wide-eyed. We had randomly struck up a conversation, which then led to a joyful, platonic romp through Rome. Looking at it now, this image literally documents the moment my love affair with traveling alone — and never knowing what any given coordinates have in store — began.

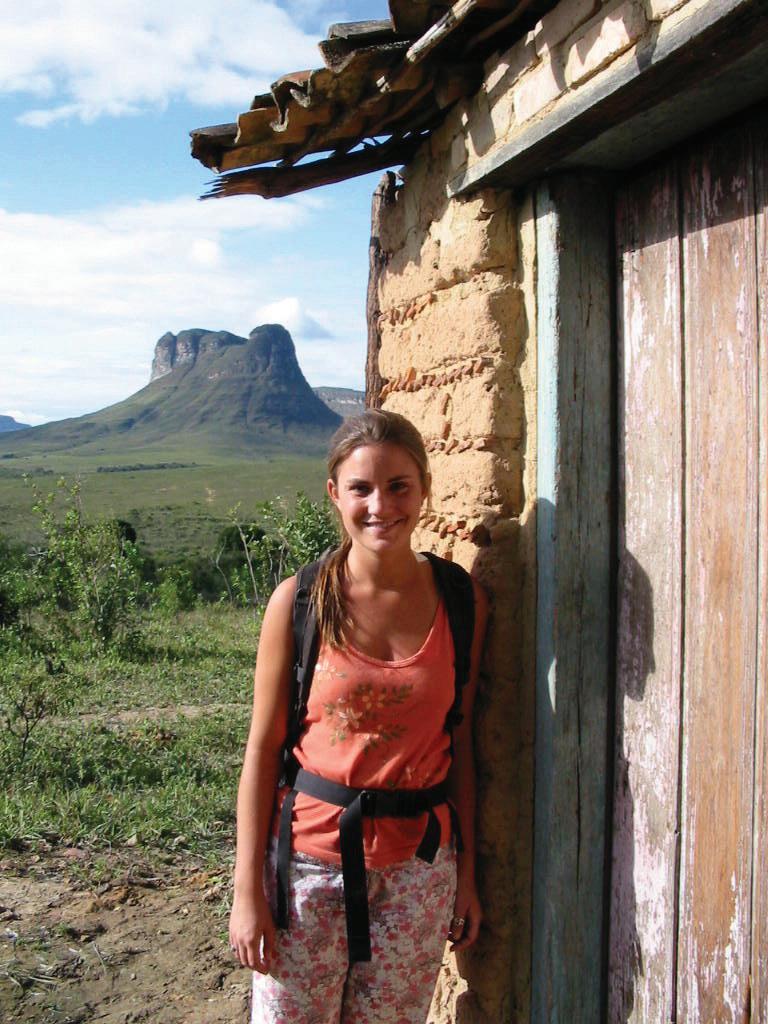

Avins

I was 20 years old in Chapada Diamantina National Park in the interior of Bahia, Brazil, on my way to study abroad in Rio de Janeiro. I had a lot of fear about going to Brazil — everyone kept telling me gravely to “be careful.” But I felt compelled to go. My first few weeks at a homestay in Salvador, Bahia, were rough. My host was a staunch evangelical; my Portuguese wasn’t catching on; my stomach was upsidedown. But two dear friends (and The Lonely Planet) all told me that this park was magical. I made a reservation at a pousada from a payphone, and got on a bus in the wee hours of morning, leaving the city during Carnaval by myself. Everything clicked here. All the Portuguese paid off. I hiked, swam, and climbed into an old Suburban with a gaggle of stoners from São Paulo. I fell in love with a friend for life. When I look at this picture I feel so much relief this girl found her path, and her people. This was where I learned that so much of adventure is simply about showing up.

Luis Rincón Alba writer, The Bigger Picture

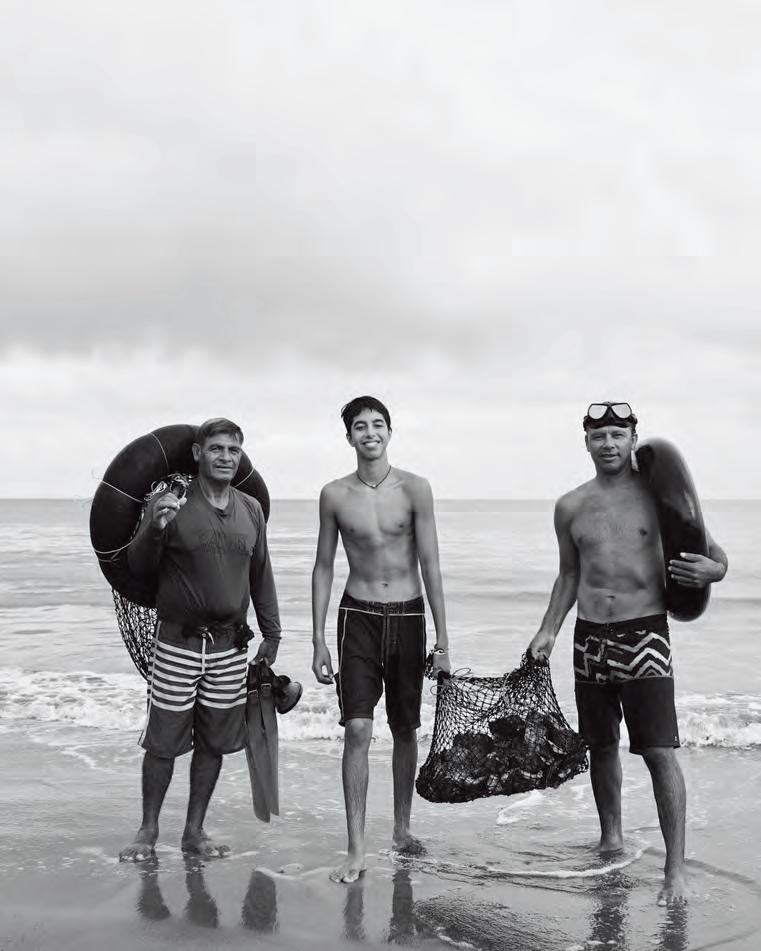

My first significant trip was to visit drummers in a maroon town on the Caribbean coast of my native Colombia. They taught me that a drum holds more information than any library ever could. Since then, most of my travels (research) have focused on attuning my ear to the detailed and attentive listening required to uncover histories that remain hidden in plain sight. I teach this approach to my students at New York University’s Tisch School of the Arts where I am currently an Assistant Professor in the Department of Art & Public Policy.

Sinna Nasseri photographer, Super Natural

In 2019, I took a trip to the Amazonian state of Pará with Amazon Watch. We stayed with the Munduruku people and I photographed illegal logging and mining operations that negatively affected the region’s Indigenous communities. The experience deepened my natural inclination to live simply among those you love.

Discover world-class wellbeing retreats where you can connect with your personal goals to grow well while enjoying customized spa treatments, luxury accommodations, and exquisite fare from Sensei by Nobu

Greater Palm Springs, CA

EDITOR-IN-CHIEF

Skye Parrott

EXECUTIVE EDITOR

Erin Dixon

EXECUTIVE CREATIVE DIRECTOR Alex Wiederin

HEAD OF PARTNERSHIPS & COMMISSIONING EDITOR

Elysha Beckerman

DESIGN & VISUALS DIRECTOR Lisa Lok

ART DIRECTOR, PRINT

Michael Ricardo

HEAD OF PRODUCTION

Elissa Polls

EDITOR-AT-LARGE

T. Cole Rachel

SENIOR EDITORS

John Chuldenko

Alex Frank

EDITOR, ARTS & CULTURE

LaTonya Yvette

ASSOCIATE EDITOR & STRATEGIST

Mia Sherin

DESIGNER Nishi Patel

SOCIAL STRATEGIST Annie Lin

DEPUTY EDITOR

Jackie Risser

SENIOR EDITOR, JEWELRY & ACCESSORIES

Shannon Adducci

CONTRIBUTING EDITORS

Khira Jordan

Jeremy Malman

Maggie Morris

Mina Stone

SOCIAL MEDIA MANAGER Alessandra Berge

EDITORIAL INTERN Anna Kaplan

NEWSLETTER CONTENT MANAGER Hassan Ali

RETOUCHING AND PRE-PRESS The Logical Choice Group

SALES DIRECTOR

Gary Armstrong

SALES MANAGER Sophie Clark

PRINTING AND DISTRIBUTION The Logical Choice Group

CONTRIBUTORS

Luis Rincón Alba, Nacho Alegre, Daisy Avalos, Jenni Avins, Hisham Akira Bharoocha, Christopher Bollen, Aya Brackett, Juan Brenner, Alexandra Brodsky, Adam Brown, Cedric Buchet, Francis Ford Coppola, Elliott Cole, Francisco Costa, Bryan Derballa, Daniel Dorsa, Joséphine Dorvall, Eliza Dumais, Thomas Dupal, Matt Dutile, Camila Falquez, Stefan Giftthaler, Emanuel Hahn, Carla Hall, Mark Hartman, Sakshi Jain, Maira Kalman, Laura La Monaca, Arianna Lago, Levi Mandel, Shirley Manson, Anne Menke, Sinna Nasseri, Ilyass Nazih, Danielle Neu, Erwann Petersen, Jess Rotter, Eyal Shani, Julia Sherman, Kat Slootsky, Chad Silver, Laura Smith, Lisa Sorgini, Michael Stipe, Stephen Tayo, Hana Waxman

SPECIAL THANKS

Lani Adler, Steve De Luca, Claudia Haspedis, Zia Heller, Jay Meyer, Virginia Scott

The DOSSIER : A collection of thoughts, ideas, recommendations, and discoveries from all over the globe.

Lisa Sorgini, photographer

Orahovac is a tiny fishing village on Boka Bay, surrounded by the tallest mountains. I discovered it by chance this summer and ended up spending a month there. It remains a sleepy place, with a rhythm that you can tell has stayed the same for a long time. For me, it had an air of mystery and magic — and my daily swims in the silent bay are something I will return to in my mind for many years.

Shirley Manson, singer-songwriter

This is a bedroom window in Edinburgh. It is home to me on the island I hail from. Watching the sea, as I do from this window, has taught me so much about life and living. About rebirth and resurrection. About forgive-

ness and forgetting. About memory and time and letting go. The mystery of the tides will do that to you. So, yes — this is my most favorite outpost and outlook of anywhere in the world, at any time at all.

Eyal Shani, chef

When asked to send an image of a notable place, I thought about so many places that have seduced my heart — faces, landscapes, objects — and something that could represent them. And I found that a tray of roasted aubergine is an inner landscape of myself.

They represent the rare reason for living: When you are touching something that suddenly becomes all worldly, catching all your experiences, letting your hands move through it without thinking, and getting a new life that is a crystal of their wishes … That is the perfect place for me. Nothing is missing, nothing extra added. Perfection. Purity.

Julia Sherman, author and cook

In Madrid, I always eat wild mushrooms with a fried egg for lunch at El Cisne Azul, because radically simple cooking is the most aspirational.

Francis Ford Coppola, film director, writer, and producer

Erin Dixon, executive editor of Dossier

Nestled in Monti, every local’s favorite Roman neighborhood, Casa Monti Roma is both unmistakably of its place (eclectic like its historically artistic rione, yet effortlessly refinedlike Rome) and delightfully unlike any other hotel in the city.

The newly opened familyowned boutique property’s decor is a joyful riot of bespoke graphic textiles and custom hand-painted ceramics. Mediterranean hues, original artworks, and curated bookshelves collectively exude a cinematic sprezzatura , ease and elegance — w ith charmingly eccentric, modern touches that extend to the hotel’s fanciful bar and ristoranti , each serving contemporary takes on traditional Roman dishes.

On the fifthfloo, the capital’s �rst Susanne Kaufmann spa serves up a marble jacuzzi alongside journey-worthy massages and facials. Then there’s the rooftop terrace — quite possibly the city’s new best-kept secret, tucked away from the crowds, with unobstructed views of dusty

cupolas and sun-bleached terracotta peaks, framed by Rome’s famous hills and umbrella stone pine trees. It’s ideally enjoyed in the evening with a classic aperitivo or house cocktail, as the city’s pastel sunsets suffuse the sky and church bells peal.

Below, native Roman Alice Beltri — who recently returned to the city to join the Casa Monti team after working for fashion houses ranging from Dior to Valentino, traversing Milan and London — reveals a few other lesser-known treasures worth venturing out to visit.

Something to taste … La pizza al taglio at Roscioli and carciofi and calamari salad from Trattoria da Teo in Piazza dei Ponziani. Do not miss Camponeschi Ristorante and its wine bar. In Piazza Farnese, enjoy an aperitivo at Circoletto Roma, overlooking Circo Massimo — and try the pizza with pastrami. If you’re looking for classic Roman dishes, try Giulio Passami l’Olio or Felice a Testaccio for the best cacio e pepe.

Something to see … Panoramic views and sunsets from Gianicolo Hill, passing by Fontana dell’Acqua Paola.

A secret spot … Libreria Libri Necessari is a small

Thinking on Your Feet Maira Kalman, author and illustrator

When in New York, always walk as much as you can because all is revealed when you walk. You can see what you need to see and … etc.

Illustration by Maira Kalman from The Principles of Uncertainty. Kalman’s newest book Still Life with Remorse was released October 15, 2024.

Michael Stipe, singer-songwriter

Vienna is a great place to go and experience art. The last time I was there, we went to two openings and five museums in a single day — and we stayed at one of the best hotels ever: The Guest House.

books tore in Via degli Zingari (in Monti), where the owner hand selects pre-owned and antique books.

Something to take home

… Toko is the best spot for vintage-inspired jewelry. I especially love the signet rings. Le Tre Sarte for welltailored, handmade, made-toorder wardrobe staples.

Only in Rome … Edicola Erno is a new concept from Edicola Romana located in a charming piazza near Borgo Pio, offering curated magazines and coffee table books, pop-ups, and events.

Jackie Risser, deputy editor of Dossier

Many arrivals to St. Barths start similarly, with a puddle jumper (by Tradewind Aviation if you’re lucky) that lands on a teensy runway and a drive on will-we-or-won’t-we-fitroads that wind through topsy-turvy terrain and bustling villages. But only the best travel days end with the ocean steps from your passenger seat. That’s the magic of Le Barthélemy Hotel & Spa.

Nestled in Grand Cul-deSac, the retreat hugs a crescent bay, meaning: The beach is never more than 100 feet from the property’s open-air lobby. The gentle waves prac-

tically beg you to wade waistdeep into them with a glass of house cuvée or to paddle to the nearby coral reef alongside sea turtles. There’s even a Coral Restoration experience, one of many sustainable practices that have earned Le Barthélemy a prestigious Green Globe Certifiction this year.

Sticking to the sea theme, Le Spa at Le Barthélemy pairs an atrium with a sauna, Nordic baths, and (glow-inducing) La Mer facials — La Mer skincare gaining healing properties from seaweed, naturally.

Dinner at Abyss, meanwhile, tapped me into the flvors of the place. I savored mahi mahi carpaccio in a citrusy sauce that my server urged me to

soak up with fresh bread, and sole that felt like taking a bite out of the Caribbean — both crafted by the island’s first Michelin-starred chef, Jérémy Czaplicki. Seven Stars Bar also delighted this astrology lover with its 12 zodiac-inspired cocktails, including the Cancer, which was gingery, coconutty vodka heaven.

The hotel organized a rental car and a private boat cruise for me, too. Gliding along cliffs, by land and sea, I laughed at how often I uttered “Oh, my word,” amazed by the raw beauty surrounding me. How divine it was, then, to tuck into my luxurious, serene Sybille de Margerie-designed guest room at the day’s end.

Off-Center

Carla Hall, chef

When in Chicago, always look for restaurants on the outskirts of the metropolitan area. There you will findthe local spots that give you access to the cultures that make up the city. I recently found Dino’s Italian Pizza & Italian Restaurant and ate the best minestrone, served by the friendliest waitstaff.

The couple are retired school teachers who built a hanok on a hill in a rural part of Korea called Damyang-gun. It was the fist time I got to explore rural Korea as an adult, and I was captivated by the idyllic beauty of the countryside, a place where people took more time to appreciate the little moments of life. The kind hospitality shown by this couple made me immediately feel like family, as they implored me to stay longer and to visit again. It made me dream about building an escape for myself in the future, to connect to my cultural roots.

Force of Nature

Anne Menke, photographer

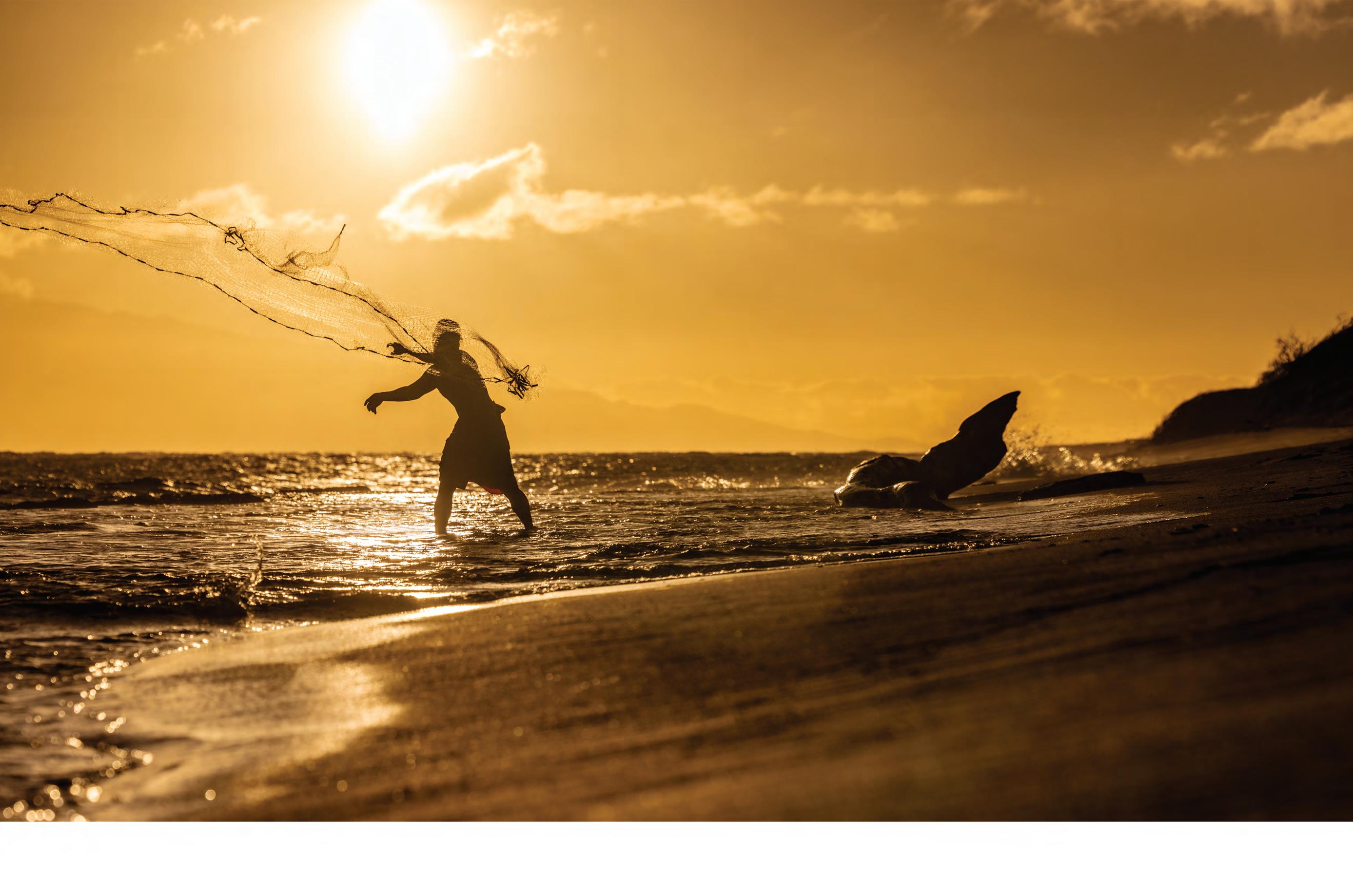

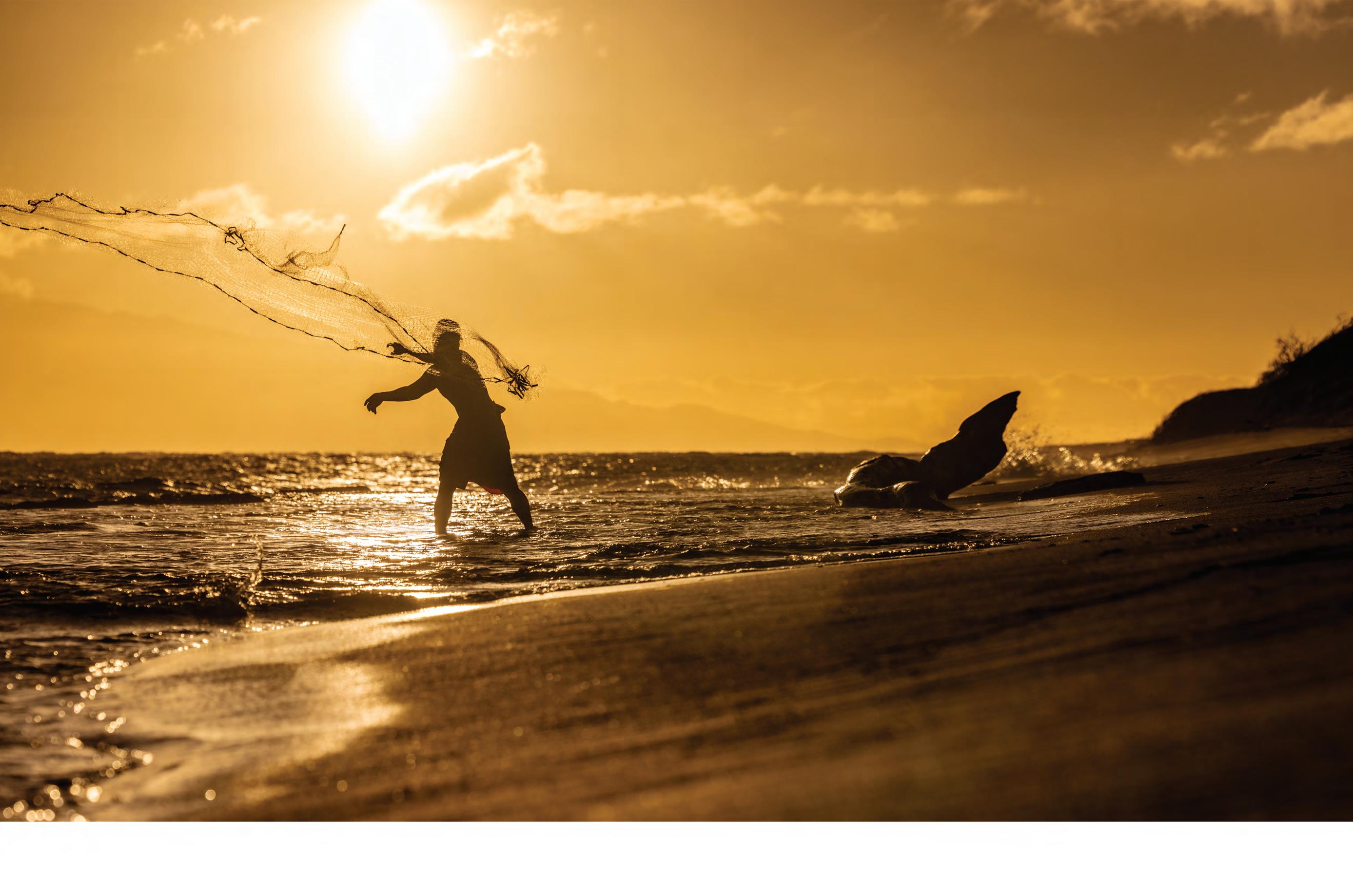

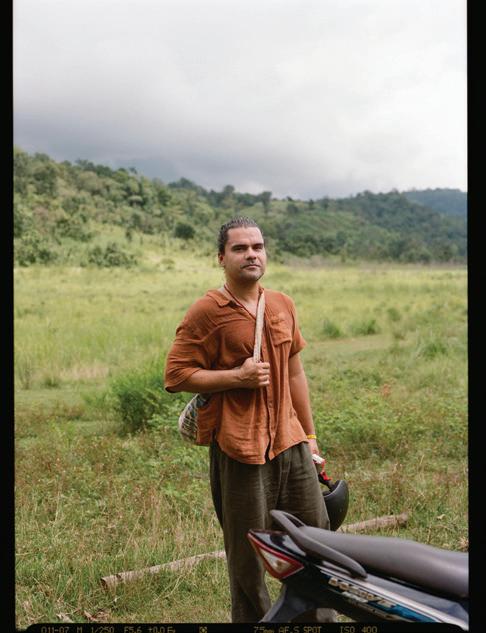

This photograph was taken during our trip to Indonesia last year. It’s at Ngalung Kalla in Sumba, an ecological

retreat that’s just a special place to stay. No words can describe it. My kids — teenagers — had the best time exploring the property and its permaculture garden, meeting locals in the village, and

learning about the culture. Christian Sea, one of the retreat’s owners, is a famous Hawaiian waterman. We went spearfishingwith him for our dinner. It was truly magical.

New York has some similarities with my home city, Lagos, Nigeria, and I find the streets truly inspiring to observe. There’s something particularly captivating about this young B la ck boy who I saw in Soho. He’s impeccably dressed, focused, at work. His appearance, the attention to detail in his attire, is simply beautiful to witness.

Reality

Adam Brown, founder of Orlebar Brown

In a city like London, inspiration happens organically, as A dam Brown, founder of Orlebar Brown — the esteemed men’s swim and resort wear brand, now under the Chanel umbrella — shares.

“London’s bustling streets, rich history, cultural diversity, and culinary delights captivated me. I felt like I was living the dream. Its dynamic blend provided everything I could ever want in a city.” Here he

reveals where he eats, drinks, and simply enjoys the moment.

Something to taste …

There are a few spots that truly stand out for me. One of my favorites is the iconic River Café in Hammersmith, where every dish feels like a culinary masterpiece. For plantbased delights, Farmacy in Notting Hill is an absolute must-visit. And for a taste of local flvor and vibrant atmosphere, Strakers on Golborne Road offers a dining experience that’s as authentic as it gets. For drinks, I favor the

Blue Bar at The Berke-

ley, designed by my late friend, David Collins, which holds many cherished memories. Additionally, for those who can secure an invitation from a member, Maison Estelle.

Something to see … The National Portrait Gallery, V&A Museum, Wallace Collection, Columbia Road Flower Market, Dover Street Market, and any bustling street. My personal favorite is the National Portrait Gallery for its rich historical context and artistic inspiration.

A secret spot … Simply sitting on a bench in one of the Royal Parks, such as Kensington Gardens, Regent’s Park, or The Green Park, to observe people passing by. Kensington Gardens is a special place for me, but each park offers its own charm and atmosphere. Something to take home … Anything from Connolly would be a great choice.

Only in London … Walking along the River Thames from Battersea Bridge to Tate Modern on a sunny Sunday morning is a London experience like no other.

Daniel Dorsa, photographer

Last November, after three years of waiting due to the pandemic, my wife and I were finallyable to go on our honeymoon in Japan. We traveled around the country for 17 days in perfect fall weather, watching Japanese maple leaves turn colors, eating everything in our path, and feeling the strong sun wash over us.

While there, we spent a day in Nara Park, aka the “deer park,” situated at the foot of Mount Wakakusa. With a brisk breeze at our backs, we explored this rather large park full of deer that had lost their instinctual fear of humans and replaced it with curios-

ity. Some would bow at you to receive a treat, while they all roamed the grounds knowing this is their home and we are simply visitors.

This image captures a candid moment: a man surrounded by deer, casually reading the paper. I never spoke to this man, but I felt like he naturally belonged here. His all-white outfit,illuminated by the sun behind him, gave him a nearlyangelic presence.

As quickly as he appeared before me, he walked off. It was almost as if he was there just for the picture. My wife and I spent the rest of our afternoon feeding deer and watch-

ing the sunset from a big hill, entranced by this magical place — but we never saw him again.

For your files … Beyond enchanting nature, Nara and its neighboring prefectures are renowned for their fertile ancient and contemporary culture. Shrines and temples surround Nara Park, which itself houses Tōdai-ji Temple, home to the world’s largest bronze Buddha statue. And just an hour away, Kyoto reigns as the country’s arts and crafts capital — as well as the birthplace and current center of Japanese tea.

Try your hand at kintsugi, the art of repairing broken pottery

at Pieces of Japan Studio or Roku Kyoto. Or experience the craft of Kyo-karakami, a type of paper that is handprinted using patterns carved into magnolia woodblocks, at Ritz-Carlton Kyoto. The sixseat Tearoom Toka serves up a traditional ceremony in a 100-year-old townhouse that evolves into a perspective-shifting journey, while on the city’s outskirts you can encounter yet another of the country’s high arts: Rakushisha, a thatched cottage now open to the public, was once the home of Mukai Kyorai (1651-1704), a disciple of Japan’s beloved haiku master Matsuo Bashō, who also visited and wrote about the site many times.

Francisco Costa, founder of Costa Brazil

Francisco Costa spent 13 years as the creative director of Calvin Klein before he took a sharp right, founding Costa Brazil, an ethical, eco-bene�cial skincare brand, in 2018. Centered around rare, natu-

Aya Brackett, photographer

This photo was taken in Tuscany, Italy, at the Bagno Vignoni hot springs in the Val d’Orcia Park. In the Middle Ages, the springs were a stopping point on pilgrimage routes stretching from Rome to Canterbury, England. When I was there a summer rainstorm approached, but the sun broke through the darkening clouds and illuminated bathers under a thermal waterfall. I was struck

ral Amazonian ingredients fr om Costa’s native Brazil, its products smell lush and voluptuous like a tropical night. Earlier this year, Costa bought the brand back from its parent company, with future-forward plans to return it to its roots, physically

and philosophically. Here he shares his favorite spots in his favorite place to visit in his home country: Rio de Janeiro, because he says: “It embodies the essence of Brazil.”

Something to taste … Picadinho and fresh fruit juice from Restaurante Guimas

Something to see… Insti-

tuto Moreira Salles

A secret spot … Praia do Abricó

by how modern and ancient people share an essentially unchanged experience in these warm, salty, turquoise waters.

For your files … While there is no shortage of wondrous places to stay in Tuscany, here are a few of our favorites (brought to you by the letter “C”): Castelfalfi, Castello di Vicarello, and Rosewood Castiglion del Bosco.

Something to take home … Saudades , a Portuguese term that characterizes the poignant desire for something lost or something that might have been.

Only in Rio … The magical sunsets at Arpoador.

Laura La Monaca, photographer

While my job as a photographer often takes me to brea thtaking locations, it’s the people I encounter who truly enrich my experience. And since moving to Hawai‘i, I’ve come to love the islands’ distinctive blend of natural beauty and cultural heritage. During a recent project at Hotel Wailea in Maui, I had the privilege of meeting Lauren Shearer, a local floral artist with a deep connection to the ‘āina (land).

Lauren’s passion for creating beautiful leis is evident in every piece she makes. She takes great pride in foraging her own flwers, ensuring that her creations not only look spectacular but also re�ect the island’s natural beauty.

For your files … It’s been just over a year since fires ravaged Maui, and conscientious tourism remains a cr itical driver of recovery. If you’re planning a trip, we’re partial to the Iao Valley Inn, a bed-and-breakfast situated within Mahina Farms, which offers cultural workshops and farm tours, connecting guests to the land and Hawaiian culture. Likewise, the Four Seasons Resort Maui at Wailea offers “A Wayfiner’s Journey” experience with Kala Baybayan Tanaka, one of Hawai‘i’s leading female navigators. To sample signature island flvors, head to Ocean Organic Farm and Distillery for one of the best lunches on the island and MauiWine, an island institution since 1974, for memorable vintages and panoramic views from 1,800 feet above sea level.

Elliott Cole, photographer

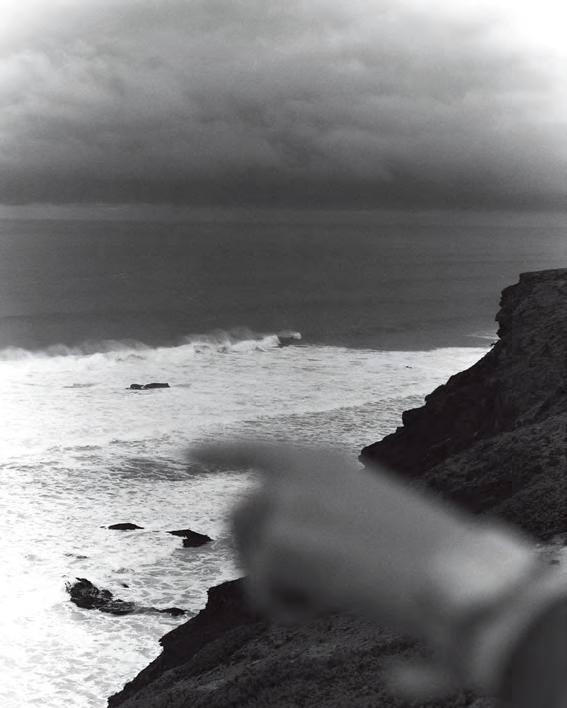

Towards the end of last year, my family and I decided to spend the month of January somewhere outside of the Unit ed Kingdom, away from the gray and damp. This would be our �rst overseas trip with our 8-monthold daughter. My partner was still on maternity leave and, typically, I don’t have much work in January, so we rented out our place and booked an Airbnb in southern Portugal. We found ourselves surrounded by orange groves and sweet potato fields, between the town of Rogil and the cliffs overlooking the

Halcyon Horizons

LaTonya Yvette, arts & culture editor of Dossier

It has been nearly a year since I flw from Dakar, Senegal, to Accra, Ghana, where I spent 72 whirlwind hours immersing myself in its intimate, impactful creative culture. And it’s been approximately 12 hours since I imagined returning to the capital. Perhaps that’s what happens when you only have three days to commune with a place that immediately speaks to your soul. I’ve explained this to myself as a sort of mediation: It’s what happens when you only spend 72 hours somewhere. I repeat it as a salve, an attempt to quell my longing for this still mostly unknown place. One day I’ll return, when the pace of life and other travels make it so. Until then, I’ll tend to my desires on the page.

For your files … Sample the menu at Kōzo, where African flavors mix with Japanese and Thai cooking techniques. Visit dot.ateliers visual arts center and artist residency for an exhibition. If time allows, take an hour’s �ight to Tamale to visit the Savannah Centre for Contemporary Art, a revolutionary artist-run project space, exhibition, and research hub created by Ibrahim Mahama. Just be sure to return in time for a beach sunset (or sunrise). A stay at centrally located The Kempinski Hotel Gold Coast City Accra makes it all possible — and houses a great tennis court.

powerful winter swells of the Atlantic Ocean. These pictures represent a grounding time, when we were able to slow down, sit outside, breathe, and be as a family — to get used to that new feeling.

Matt Dutile, photographer

At the northernmost reaches of Lhuentse, one of the least populated districts in the Himalayan nation of Bhutan, rests the imposing Dungkhar nagtshang (manor home). Near the country’s border with Tibet, this incredible estate is the ancestral home of Bhutan’s royal Wangchuck dynasty. In and of itself, it is a truly spectacular sight. But

when the young monk who had been our guide through the four-story structure began throwing the folds of his brilliant red robe over his shoulder, it was a moment I knew I had to capture. The folds of the fabric felt alive as they caught the wind. The photo encapsulates much of what I love about this Buddhist kingdom: incredible architecture, spirituality, and fleting moments of grace at the end of a road less traveled.

Bryan Derballa, photographer

The dunes in Wahiba Sands have a uniformity — all these billions of grains of sand create a singular block of color. But then, there’s an ephemeral geometry from the wind constantly blowing the dunes around and the way shadows shift throughout the day. The shapes are in constant fluxand are never quite the same day to day. It’s that tension, between the uniform and the ephemeral, that I loved so much. I could just lose myself shooting those dunes. It’s also easy to get physically lost, which fortunately I did not.

Mind Games

Levi Mandel, photographer

Near the entrance of Monte Albán, a massive archaeological site in the Mexican state of Oaxaca, lie the ruins o f a Mesoamerican tlachtli (ball court). Thought to be constructed somewhere between 200 and 500 B CE, the tlachtl was one of many similar ballcourts built throughout the historic region.

During Aztec rule, ollama (the ritual ball game played on the courts) was for nobles, often accompanied by heavy betting. Only the elite were allowed to witness these games, with leaders and important guests seated at both ends of the court. Play-

ers wearing heavy padding would use elbows, hips, and knees to knock a hard rubber ball through vertical stone rings at opposite ends of the court. Multiple myths mention the game, which was extremely violent and typically ended in numerous injuries. It’s also said that the winning team would sometimes sacrifice themselves to the gods.

It’s always a humbling experience standing on sacred land. Leaving my group to explore solo, I shut my eyes and picture the space filledwith music and noise. I imagine what smells might have wafted through the air, perhaps trash and decay,

but also smoke and food and spice. My eyes are still closed and I’m lost in thought when my wife nudges my shoulder. We walk back to our air-conditioned van to continue our adventures through Mexico.

For your files … For a different perspective on Oaxacan history and culture, visit Casa Viviana in Teotitlán del Valle, where generational craftswomen are transforming traditionally seashellshaped ceremonial beeswax candles into mind-blowingly ornate flwers and more. For equally evocative clay objects, visit 1050 Grados in Oaxaca City, where a cooperative of potters employs storied techniques to craft simply elegant vessels glazed in the rich hues of the surrounding geography.

While in the capital, make sure to also peruse the handwoven, handmade, naturally dyed textiles of Mexchic, created by a team of local women, trained in-house in couture sewing techniques. And don’t miss Juana la Vintage, a trueto-its-name shop housing a psychedelic kaleidoscope of rare treasures. As for lodging, Casa Criollo, a serene two-bedr oom residence in Oaxaca, curated by chefs Enrique Olvera and Luis Arellano and situated behind its namesake restaurant, intertwines the region’s cuisine, art, and design to mesmerizing ends, while Hotel Escondido combines old and new, local and international, into a custom eight-room property in the Valles Centrales region.

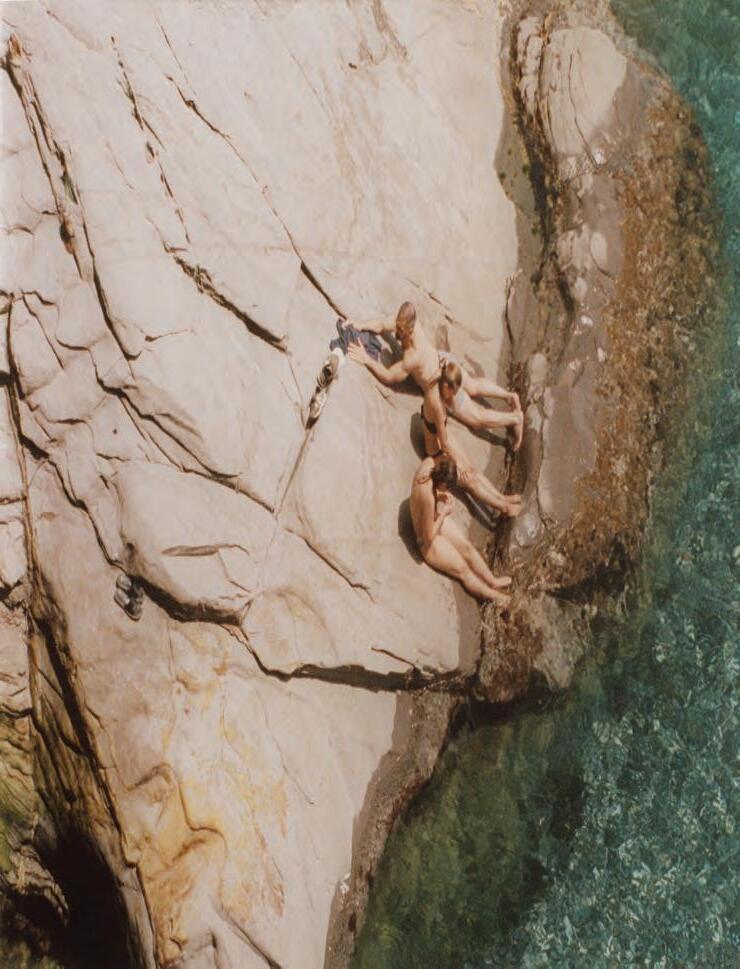

Arianna Lago, photographer

For the past three years, I have been traveling to the Ligurian coast to gather photographic material for a personal project. I love returning to this part of Italy because it evokes a sense of safety and sentimentality, reminding me of my childhood, even though I only began visiting as an adult. It’s as if time has stood still here: the children’s lifestyle of today closely resembles my own when I was young, allowing me to reconnect with how life was before I left the country.

When I am here, I usually begin and end my day with a swim, timing it for when the beach is deserted and the sun is tucked behind the hills. The water is invigorating, and being alone in the sea is a special

experience. Swimming while admiring the coast’s pastelcolored facades is like being on a Wes Anderson movie set.

My days are spent wandering, seeking authentic scenes of everyday life — teenagers diving off rocks or sunbathers pr ecariously perched on cliffs, searching for solitude. The rocks have a distinctive grayish tone with white streaks. Unique to this area, they remind me of a Luigi Ghirri photograph.

them between my finers, and inhaling their scents.

On my most recent visit, I unexpectedly ran into a friend from Los Angeles, which made me realize that this once-hidden gem has gained global popularity. But I hope it remains as I remember it, preserved in a nostalgic bubble.

Hours are also infused with sensory pleasures: the smell of home cooking wafting through the air, the sound of cicadas, and the sundry aromas of wild plants growing on the cliffs, such as figleaves, sea fennel, and wild fennel. I love picking them, rubbing

For your files … Located in northwest Italy, Liguria is an enigma, alternatively associated with Cinque Terre’s overrun beauty and Genoa’s (once) industrial grit. Within this spectrum lie endless cliffs and towns ripe for exploration. Our favorite home bases include the Renzo Piano-designed NH Collection Genova Marina, which welcomes guests with a brass-trimmed bar and wood-paneled rooms,

adding a cinematic quality to its nautical setting. Similarly maritime, but located in Portofino, Splendido Mare, a Belmond Hotel is an intimate, 14-room guesthouse located on the town’s scenic cobblestoned wharf, bordering its town’s main (charming) piazzetta. Royal Hotel Sanremo, in its namesake town, is a 126-room hotel within an unapologetically gilded palace. It’s surrounded by a subtropical garden with a beach club, three restaurants, and spa, but its idiosyncratic Gio Ponti-designed saltwater pool is reason enough to visit. Finally, Grand Hotel Miramare, an iconic 120-year-old, family-owned property in San Margherita, offers intoxicating Felliniesque grandeur along with those distinct Ligurian Sea views.

The next generation of Rolls-Royce artisanship in perfect harmony with electric technology. Embark on an unprecedented journey that sees e ortless charging fused with captivating performance.

Discover the spellbinding Rolls-Royce Spectre with a bespoke product experience*. To schedule your personalized appointment, please contact the Rolls-Royce Motor Cars North America Client Contact team via email at clientservicesna@rolls-roycemotorcarsna.com.

Around the Bend

Kat Slootsky, photographer

A bit of a misnomer for those of us who don’t casually “walk” along mountainsides in Scotland, The Quiraing walk is more of an active hike or climb — less the casual stroll one might assume. Still, it was one of the most incredible jaunts of my life … seeing the Isle of Skye from above, being surrounded by the blue sea and the rolling green hills, stumbling upon grazing goats perched along the mountain top. Then I turned a wide corner to find this Sotsman, seemingly out of a historical fition book, smoking a pipe in his kilt while looking out over the vast beauty of it all.

For your files … Follow up your Quiraing “walk” with a meal at the Corriegour Lodge Hotel restaurant. Here, fresh produce from the Scottish Highlands and regional seafood and beef star in a seasonal, ever-changing menu that includes dishes such as seared tronçon of turbot on crayfishcolcannon with steamed spinach and mussel and clam broth — served with a pictureperfect view over the Loch Lochy. After the meal, enjoy a drive through the fabled, ancient-growth Caledonian Forest. Then settle in for the night at The House Over By at The Three Chimneys. Set on the shores of Loch Dunvegan, this restaurant-inn offers more breathtaking panoramas and noteworthy (Nigella Lawsonapproved) finedining.

I love traveling with my twins. Okay, sometimes I love traveling with my twins, who are now 11 years old. This June, we visited Iceland, just a few weeks after a substantial volcanic eruption off the Reykjanes Peninsula. After a few days in Reykjavik, we rented a car and drove along the southeast section of the Ring Road, the 800-mile-loop that circles the country.

It rained our entire first week and temperatures never surpassed 50 degrees. Black volcanic rock stretched into the treeless, moon-like horizon. My daughter complained relentlessly from the back seat. I had to figt to keep the wind from shoving our tiny econo car into the highway median. I wondered if maybe I’d made a mistake bringing us all to Iceland.

Then, one day near the small village of Hvolsvöllur, we found this waterfall: Gluggafoss. There are thousands of waterfalls in Iceland and many are popular tourist destinations swarming with food trucks and tour buses. By some small miracle, we had Gluggafoss all to ourselves.

We walked a steep, narrow incline as far as I could bear before I started bawling (apparently I’m afraid of heights). Then we sat, listening to the thunderous sounds and feeling the mist shroud our faces. My son decided to sketch the view. My daughter took off her shoes and ran around barefoot. It felt majestic and intimate at the same time. I grew up in suburbia, where we cut and shape the environment into submission. How sublime, in contrast, to be in the presence of the great, brutal landscape of Iceland — a place that will not be tamed.

Words by Skye Parrott

Walking into Le Grand Mazarin feels a bit like being welcomed into the home of an older (well-to-do) Parisian woman with impeccable taste and a penchant for whimsy.

Set in the heart of the historic Marais neighborhood of Paris, the hotel is the fourth from Maisons Pariente, the family-owned luxury hotel group run by Patrick Pariente (co-founder of French fashion brand Naf Naf) and his two daughters, Leslie and Kimberley. The interior design of the properties, somehow feeling both homey and eminently Instagramable, has become a hallmark across their portfolio, with Le Grand Mazarin, their fist property in Paris, adopting a more cosmopolitan character.

Kimberley, who drives the identity of each hotel, shared that one of the ideas behind the design was to create the story of a cast of artists who had stayed there over the years, each leaving their mark as a gift for the hostess.

The pool feels as if a painter took a dip, looked up at the plain white ceiling and thought, “I could do something with this.” The

result: It’s as close to swimming inside a painting as one can get.

The guest rooms are similarly multitextural, with custom, modern furniture featuring fanciful flourishes mixed with antique French tapestries and traditional palettes. The eclectic style is incredibly cozy and can give one the sense that they are stepping into an incredibly well-appointed stagecoach from an early Wes Anderson film.

But it’s not all about the eye candy. The hotel’s restaurant Boubalé, led by Michelinstarred chef Assaf Granit, features Eastern European Ashkenazi fare, which Pariente described as “the last cuisine that hasn’t been made fancy.” The herb salad is one of the most delicious things I’ve tasted, ever.

Words by Erin Dixon

Smack in the center of Rome between the Trevi Fountain, Pantheon, and Victor Emmanuel II Monument, Piazza San Marcello can feel like a vortex: of tourist hoards and their flag-bearin leaders, of clustering government officialsfrom the nearby Senate and Cultural Ministry, and, naturally, of actual Romans. But this easily overlooked piazza is actually a portal — to ancient Rome and to a future rebalanced self.

Six Senses Rome is housed within the piazza’s UNESCO-listed Palazzo Salviati Cesi Mellini, which was built as a shared residence in the late 15th century by the three noble families that give it its name. The property became an open-air arcade in the 1900s, housing a cinema and shops, then the Bank of Rome in the 1970s.

These layers juxtapose harmoniously in the hotel’s serene, plant-swathed lobby, but the building’s true origins can be seen on the ground floo, through glass floortiles that reveal what is thought to be the city’s oldest baptismal font. Dating back as far back as the 4th century and connecting by underground passage to the adjacent Chiesa of San Marcello del Corso, it still holds water in its basin, setting a spiritual stage for the hotel’s newly constructed Roman thermae.

Reproductions of ancient Roman baths, the three pools follow the traditional circuit of calidarium (hot), tepidarium (tepid), and frigidarium (cold) while refleting Six Senses’ present-day promise to help reconnect you with yourself, others, and the world around you via a holistic six-pillar wellness philosophy. The brand has gained global fame for its pioneering blend of ancient healing practices, biohacking technologies, and destination-driven culinary and cultural offerings, but never before has it dropped them in the middle of a city: Rome is the fist urban offering from Six Senses, with London, Milan, Dubai, and Bangkok properties slated to debut in 2025.

The authenticity of the brand promise is realized for me via a treatment performed by the hotel’s visiting practitioner Suraj Varma, an ayurvedic guru from Kerala, India, whose intuitive understanding of my physiological state seems to channel a higher power — perhaps it does, here in this legendarily sacred place, blessed by atoning waters. Varma concludes my transformational therapy with a purifying discourse on healing: “Go slower,” he says. “Have real faith.”

Words by Mia Sherin

I arrived at the Conservatorium Hotel in Amsterdam in a haze, one created by a strong elixir of jetlag and the city’s morning fog — just as the sun was rising over its silent canals. Wandering through the property’s lobby, later described to me as the “living room of Amsterdam,” I was attuned to my rather spectacular surroundings by the din of early-rising guests and locals, which acted like a muchneeded shot of espresso.

Milan-based designer and architect Piero Lissoni redesigned the vast space around a decade ago, respecting the historical building’s significat past while shaking off any hint of dust. Scalloped, bricked walls nod to its 19th century origins as a national savings bank designed by Dutch architect Daniel Knutte, while a ukulele chandelier commemorates the property’s second life as the Sweelinck Music Conservatorium, which nurtured the city’s young musicians until 2008 and which contextualizes the hotel’s location within Amsterdam’s Museum Quarter, home to the Rijksmuseum, Van Gogh Museum, and Moco Museum. It also provides

a legacy foundation to the distinguishing artistic thread that runs through the property.

The Glass Library at the Conservatorium houses rotating exhibitions, often of contemporary artists. A wall near the fist-floorelevator houses a portrait by Bastian Woudt, a Dutch photographer who served as the hotel’s artist in residence in 2022, part of the property’s ongoing collaborations with local artists to develop its Residence Suites.

Speaking of suites, the welcome note in mine featured an original watercolor of the city. Later, over drinks with Roy Tomassen, the Conservatorium’s General Manager, I discovered that he had painted it. In fact, he paints every single welcome letter, which aptly sums up the hotel’s service: creative and extraordinarily thoughtful.

Musician, artist, and alt-rock icon Kim Gordon goes deep on the books that that have informed her life and work.

When Kim Gordon published her arresting memoir Girl in a Band in 2015, she detailed, among other things, her experience as a founding member of pioneering alt-rock band Sonic Youth, her work as a visual artist, the dissolution of her marriage, and a dissection of her California childhood.

The book was, in many ways, concerned with the subject of endings, but, ultimately, it signaled a creative rebirth for Gordon, who has spent the subsequent years continuing to write and make art and music, both as a solo artist and as a part of Body/Head. Earlier this year she released a celebrated solo record, The Collective, and has spent most of 2024 on the road. When we spoke, she was packing for an upcoming string of European shows, yet still managed to unpack the books that have most informed her life, work, and thinking.

TCR: Do you remember the fist book that really had a profound effect on you?

KG: Yes, The Lonely Doll by Dare Wright. It’s a kid’s book, but it’s kind of creepy. I must’ve been like four or fie when I fist saw this book; it’s all of these blackand-white photographs of a doll with teddy bears. There’s a baby

bear and a father bear, and all of them are placed in these very adult-seeming situations. I forget the exact plot, but the doll shows up and the little bear find her and brings her home. Later, she gets into trouble by going into this wealthylooking Upper East Side apartment and getting into the homeowner’s jewelry, putting it on. The father bear comes home and I think he spanks her. It’s sort of perverse. But there’s something really existential about the photographs that cemented in my mind this idea of what New York was and what a wealthy person’s apartment should look like. It also influened my idea of fashion in a certain way. The book itself is actually kind of depressing. I got a copy of it for [my daughter] Coco when she was little. I remember reading it again and thinking: Wow … This is kind of disturbing.

TCR: What books did you gravitate towards as you got older?

KG: As a teenager, I read a lot of D.H. Lawrence. I think it was because his books had a lot of very sensuous parts to them. They were very sexual, but I also just loved his writing. The imagery is so evocative and almost visceral. I remember loving Women in Love, in particular. It’s just such a beautiful book. I was going to reread it recently. I got a copy and started reading the intro and

was like: Oh, this is about post-industrialization. Thinking about it inspired the lyrics for a song I then wrote called “ECRP.” It’s a sort of anti-war song that collects all of these ideas that warn: This is where technology can lead you. Somehow the two were connected in my mind. I probably only started reading D.H. Lawrence because my brother was reading it or something, but I really did like his writing. So much so that I remember doing a watercolor inspired by the book.

TCR: Are there any contemporary novelists you love?

KG: Denis Johnson. He wrote great female characters. I love The Stars at Noon. The whole atmosphere of that book is fascinating. This American woman has gone to Nicaragua in the early ’80s, and there is a coup that is happening, or has just happened. She’s moving around in this very fractured country trying to survive. Claire Denis made it into a filma couple of years ago, which I have yet to watch. She had told me she was going to make it before the pandemic and Robert Pattinson was going to be in it. So I reread the book while I was stuck at home, and I was picturing him as the main guy the entire time. Then the movie comes out and it’s some other actor in the role.

“I always felt so out of place in New York, especially when I first moved there. I was just like: ‘Oh my God, I just look so Californian and middle class.’”

I just loved that book because it felt very real in the sense that it was really about [the woman’s] own crisis and identity. And even though you are getting this sense of her interior life, you still don’t totally know what’s going on with her. Is she really a reporter? Why has she really gone to Nicaragua? Anyway, I love a lot of Denis Johnson’s books. Angels is also amazing. And Fiskadoro, which has a similar atmospheric quality.

TCR: Given your California roots, it only makes sense that we’d talk about Joan Didion. If you grew up on the West Coast, there’s no escaping her.

KG: It’s true. I love so much of her writing, so it’s hard to really pick just one book specificall. After I put out my memoir, I was doing an interview and the journalist asked me if I read Joan Didion. I said, not really, that she was kind of on my list, but I never got around to it. And she was like, ‘Oh, you should, because your writing and art remind me of her.’ So I started reading The White Album and then Slouching Towards Bethlehem. I loved Play It as It Lays and A Book of Common Prayer. I just really love the way she writes and, it’s true, it connects to some common California fascination for me. My mother’s family goes way back in California. They were gold rushers who came to the Sacramento Valley. Her book Where I Was From has this essay called “Trouble in Lakewood” about this very middle-class, manufactured suburbia that was built in the ’50s for Vets and their families and to support the burgeoning Douglas Aircraft plant. The piece follows the

evolution of the development through the years. By the ’80s, it had completely deteriorated and eventually became emblematic of the emptiness of this fake, middle-class life they had tried to create. As industry left the area, everything fell apart, many of the local boys turned into bullies and rapists; the value of everything there went down. I’m kind of obsessed with real estate, so that was particularly interesting to me.

TCR: Didion writes very critically about California but, for a lot of people, even her often-withering depictions remain a romantic idea of what California is really all about.

KG: Yeah. Even as she takes it all apart, you still want to go there. I totally agree. I’ve always thought that LA had this very dark underside, but that didn’t dissuade me. I read a biography of Didion recently — The Last Love Song: A Biography of Joan Didion by Tracy Daugherty — that was really good, mostly because it also had a lot of her writing in it. Sometimes I feel like biographies don’t end up telling you much about the actual person, but this one felt different. There were all these passages she wrote about driving down the highway to Palos Verdes and it being this beautiful place — not like now, where it’s just some wealthy community sliding into the ocean.

TCR: I asked Bret Easton Ellis about his favorite books set in LA. How do you feel about his work?

KG: I really loved his last book, The Shards. A big part of it was that it made me nostalgic for the areas in LA where

“I probably only started reading D.H. Lawrence because my brother was reading it or something, but I really did like his writing.”

I grew up. You know, Westwood Village, going to the Hamburger Hamlets. I love that he talks about how one of his favorite movies was American Gigolo and how it inspired him when he was in high school. I recently rewatched it and was amazed to see that it also takes place in Westwood Village.

TCR: For so many years, people really associated you — both culturally and aesthetically — with New York. Are you surprised that you ended up living back on the West Coast?

KG: I never thought about it too much until it happened, but I always felt like I carried it around with me. I always felt so out of place in New York, especially when I fist moved there. I was just like: ‘Oh my God, I just look so Californian and middle class.’ I tried to make myself look more punk. I remember the composer Rhys Chatham once said to me, “Kim, you’re always going to look middle class.”

TCR: Last but not least on your list of books was Pattern Recognition by William Gibson.

KG: This was the fist William Gibson book that wasn’t really science fition, or some kind of cyberpunk story. Again, I loved this book because the female character is so good, so interesting. It’s also about the idea of someone being a kind of “cool hunter” in the culture, trend hunting for corporations. It was a pretty novel idea at the time. I’m also very into crime-noir stuff, so I liked it a lot for that reason. Also, the Sonic Youth song “Pattern Recognition” was inspired by it.

TCR: Next year will be the tenth anniversary of Girl in a Band. Did the experience of writing that book have any affect on you as a reader — or change the way you think about other people’s memoirs?

KG: To be honest, I don’t really read that many memoirs. And now there are so many. But they are going to reissue [Girl in a Band] next year, and I think I’m going to write a new chapter to add to it. I also did this small art book, Keller, about my brother who died a few years ago. Even though it was a sad subject, I really enjoyed writing again. I guess that’s what I learned from doing the book: Not just that I could write in this way, but that I also enjoyed it.

Czinger Vehicles and its founders are shaping the future of the automotive industry — and it looks a lot like nature.

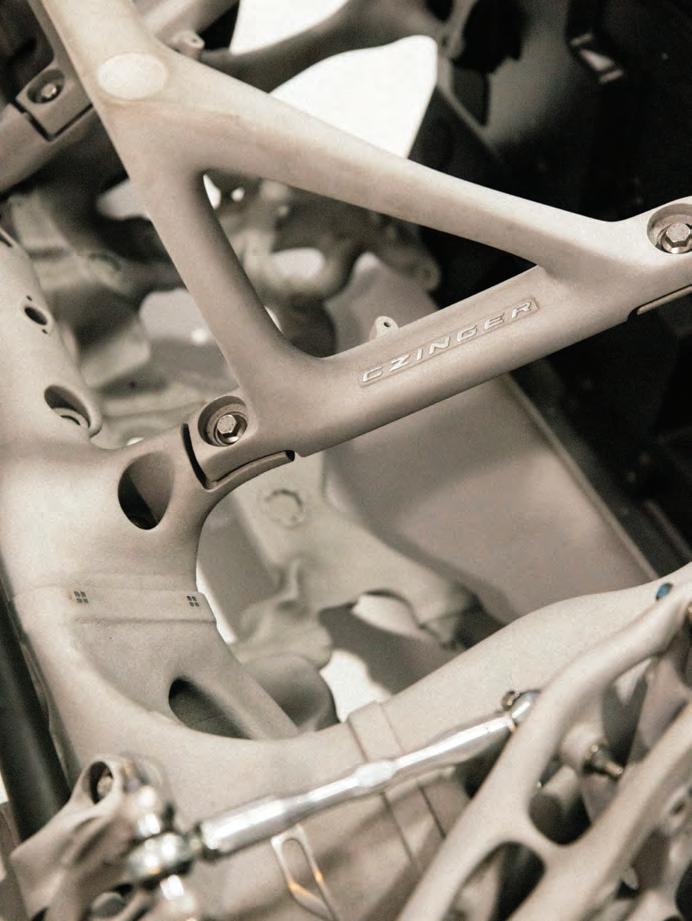

One doesn’t expect to find auto parts in an art museum.

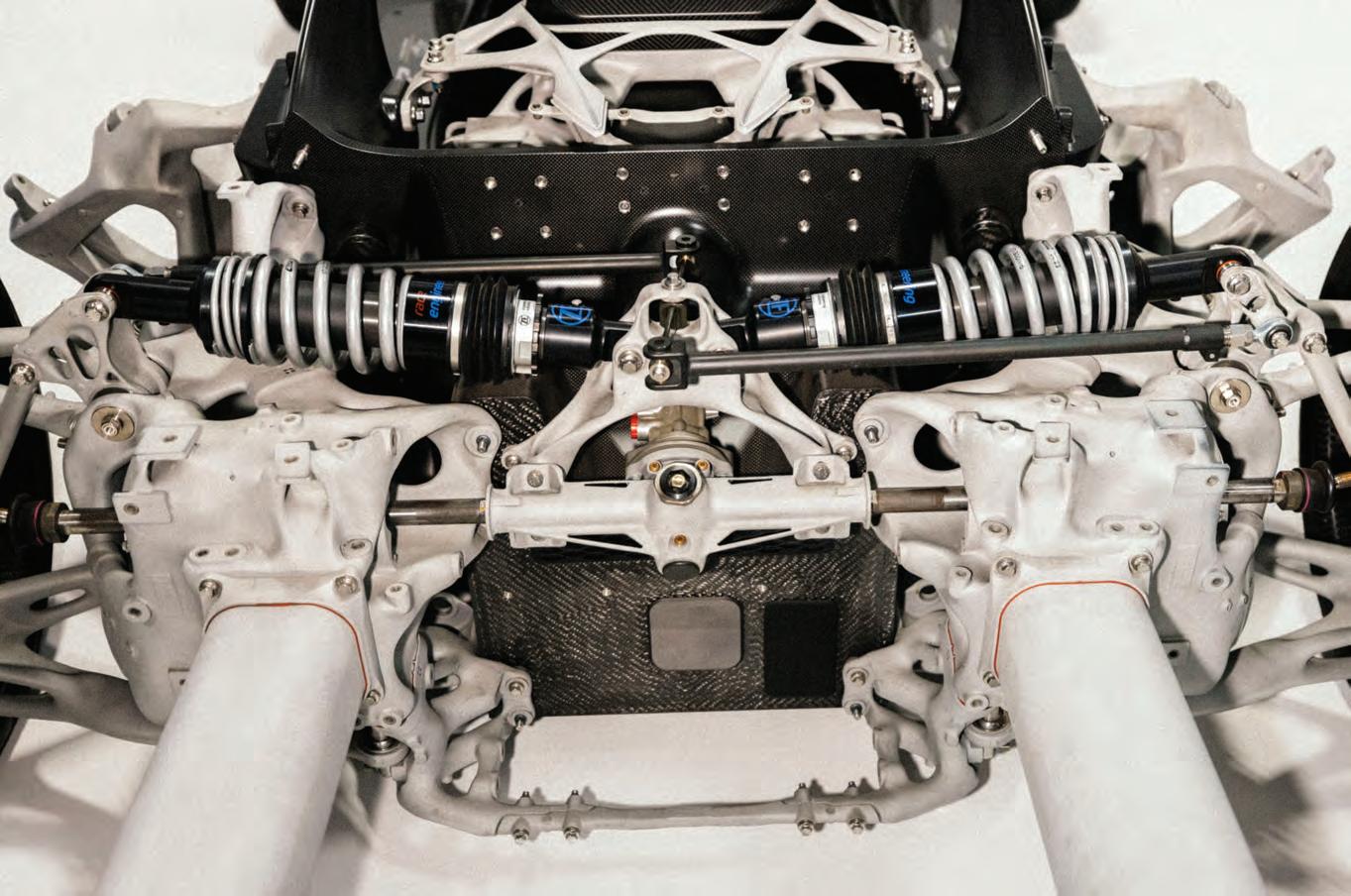

Yet at the Getty Center in Los Angeles, a rear frame perched on a pedestal is oddly organic. It looks like something culled from a jungle or snapped from a coral reef. The frame was designed and produced entirely by computers, without human intervention, at Divergent 3D in Torrance, California.

Kevin and Lukas Czinger, the father and son founders of Divergent Technologies and Czinger Vehicles, strode through their factory’s large, roll-up door like two astronauts in The Right Stuff Together they helm two companies poised to revolutionize how we make — well, almost everything. “We’re unusually close,” Lukas confided.“Up until I was seven, my dad was like superhero material for me.” Kevin threw his arm around his son for a photo. It was a warm, human connection in a building full of formidable, industrial technology.

Lukas walked me to Czinger’s latest hypercar, the 21C. Stripped of its bodywork to expose its “BioLogic Skeleton,” the chassis looked like the remains of an imaginary deep-sea creature washed ashore: fibous, freeform, cellular. It was designed by software that mirrors nature’s evolutionary process, wherein organisms compete for material and energy over millennia, continually refiningtheir structures to arrive at an optimal design. In Divergent’s human-made evolution, software is fed such design parameters: the function it’ll need to perform, the forces it will need to endure, the space it will occupy. Then the software runs thousands of simulations, mapping, designing, and refiing the object. “It’s been evolved to be perfect against a given set of requirements, just like the leaf on a tree has evolved to take in the most sun and be most water effective or compete in its niche

— in this case, [the niche] is hypercar performance” Lukas explained.

In the production area, I encountered a dozen or so assembly robots positioned in a circle, their heads bowed as if in a Kubrickian cyber ceremony. This is where the designs are realized. There are no scraps; there’s no welding, stamping, or machining. There are no trimmed pieces falling to the floo. There’s no waste. Divergent uses additive manufacturing (commonly known as 3D printing) to create whatever parts it needs, when it needs them. Designs are uploaded into printers that melt a proprietary aluminum alloy and layer it precisely where it belongs.

Peering into the printer, I watched 12 lasers dance in an intricate pattern. Once a layer is complete, an arm sweeps away the excess metal (which is later re-used), and the lasers recommence their dance. Unlike traditional manufacturing, there’s no tooling or molds. Divergent can use the same equipment to make car parts in the morning and satellite parts in the afternoon by merely uploading new instructions. Currently, 50% of the company’s business is in the aerospace sector. It also produces structures for satellites as well as surface and underwater vessels.

Beyond the factory doors, this robot’s work is tested on tarmac. Lukas told me

Czinger’s 21C is the fastest car in production. Configued like a figter jet, with the driver and passenger seated in single file it recently set lap records at both Laguna Seca and Circuit of the Americas, while meeting all crash-testing requirements and emissions regulations. Some of Divergent’s components are up to 40% lighter than its traditionally produced predecessors, which Lukas contextualized for me. “When you’re saving 20 to 40% of mass, you’re using 20 to 40% less raw material. That’s as direct and obvious an environmental impact as you can get. Scale that across millions of cars and you’ve got the biggest new automotive environmental impact technology in

the world. You’re pulling 30% less material out of the earth.”

It didn’t take long for other luxury automakers to take notice. Walking through the factory, I glimpsed parts bound for some of the world’s most established manufacturers, like McLaren and Aston Martin, marques who’ve built their reputations on creating handcrafted cars. And earlier this year I peered into Bugatti’s new Tourbillon and noticed some components tucked inside that looked unusual. Lukas smiled when I asked him what it felt like to be shipping his parts to Bugatti. “It feels awesome. What it validates is the power of this technology.

Bugatti’s a high-tech company embracing the highest technology … Right now, on chassis, [that’s] us. That’s a very rewarding feeling.”

Although technology is at the fore, people are still in the Divergent picture. In the assembly area, workers bolt the printed components together by hand, readying a car for delivery. We moved to a finishedvehicle, where Lukas swung the butterfly-hined doors upward and showed me the 21C’s interior. While sparse and purposeful, it’s full of traditional, handcrafted detail. Leathers from Scotland’s Bridge of Weir line its surfaces. “When I see the hard and soft contrast, when I see the AI-generated structures but also the artisan craft, it creates this very compelling tension and ultimately makes me want to drive the car,” Lukas explained. It’s about that engaging experience, and that’s the emotion: the performance, but also the feel. There’s an emotion to sitting in something you’ve worked on for eight years and represents the efforts of 500 people — all the near misses and all the successes all wrapped into one thing you can actually experience. For me, that’s next-level.”

In a sense, I left Divergent with more questions than answers, wondering if my perception of beauty was contingent upon its origin, if we can decouple art from artists, and whether computers can be craftsmen. But Divergent’s software has no artisan aspirations. Maybe instead these machines can act as mirrors, their evolutionary exploits sparking in us a newfound appreciation for the perfection of nature’s processing power, an understanding of the graceful distribution of a leaf pattern, the fractals in romanesco — or the subjective structural beauty that lies beneath the skin could illuminate a path to a progressive future, even if that skin is made of carbon fibe.

From wildly inventive to peculiarly orthodox, there’s always more to Claire Choisne’s Boucheron designs than meets the eye.

The idea of capturing water came to Claire Choisne during an inspiration trip to Iceland. Choisne has been the creative director of Boucheron over the past 13 years, and she was researching for the heritage French jewelry house’s latest high jewelry collection, Or Bleu. The inspiration eventually also led to the creation of a special-edition piece that uses 5D optical data storage (sometimes referred to as “Superman memory crystal”) to record the sound of moving water, depositing the audio inside of ring patterns sculpted into Glassomer (a solid silica nanocomposite that can be processed like a polymer) — all of which sits on a slick but unassuming band. The Nordic island’s black sand also captivated Choisne and her innovation team, who found a German company that could compact the sand using 3D printing and polymer binder, which was precisionsprayed onto the sand in fine layers. The creative director juxtaposed the sand with diamonds to recall the white foam of the incoming tide. Another piece, the Cascade necklace, recreates a different body of water that inspired Choisne: a sparse but vertically impressive waterfall documented in a photograph by Santino Martinez. Choisne and her team of jewelers used 1,816 white diamonds to create the jewel, which measures nearly five feet tall and can be converted into a shorter necklace and a pair of earrings.

Choisne’s collections, which take about two years from conception to realization, tap into all of the extravagance and decoration that one would expect from a Place Vendôme jeweler — only bigger and even more elaborate:

diamond-dripped bibs, exceptionally rare gemstones and out-there settings, pavéd trompe l’oeil bows and other gigantic pieces in the spirit of haute couture (belts, breastplates, epaulets), plus recreations and reinterpretations of archival pieces. Since 2020, Boucheron has divided its high jewelry collections into two categories: Histoire de Style, which pays homage to its archives and the legacy of the brand’s founder Frédéric Boucheron with collections that play up heritage details, such as the use of rock crystal or the 145-year-old Question Mark necklace; and Carte Blanche, which gives Choisne exactly that to imagine new frontiers of jewelry design and execution.

“

capsule, introduced in 2022 as something of a “concept car” of jewelry. In it, Choisne juxtaposed Cofalit, an industrial byproduct that resembles charcoal (it’s made from asbestos and other waste materials), with diamonds. “I always question what is precious. For me, it’s not the biggest diamond in the world,” she clarifies.

I always question what is precious. For me, it’s not the biggest diamond in the world.”

Ultimately, Choisne’s collections are a reflection of her — a designer who cannot be neatly categorized. Trained at the Haute École de Joaillerie, Rue du Louvre, she is as much at home on the workbenches of Boucheron’s atelier as she is in the environs of corporate luxury.

Even within these more fashionforward collections, the designer takes a meticulous approach. For example, to achieve a specific hue of red for the Tie the Knot hair jewel in the More is More collection, Choisne and her team worked for months to finally arrive at just the right color, using lacquer, titanium dyed with a cataphoresis treatment, and red bioacetate. “Nothing is ever set in stone, so we must be very agile in our thinking,” explains Choisne. “As we all share the same vision, the way we work is very fluid.”

An evolution from classic stones and materials, in fact, is one of the hallmarks of Choisne’s work. It’s visible in Carte Blanche Holographique from 2021, which explored all of the ways materials can refract light by employing holographic ceramics and different types of opals to showcase the concepts of opalescence, light rays, and light waves. It can also be seen in the Jack de Boucheron Ultime

Clad in a tailored dark suit, dark hair pulled back, stacks of Boucheron’s Quatre Classique bangles and rings on her wrists and fingers, Choisne was a picture of grace as she walked private clients through Boucheron’s installation at the Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum in New York, celebrating the brand’s new Madison Avenue boutique, which opened this fall.

In spite of the opulence her work reflects, privately Choisne reveals an appreciation for simple curiosities. In her spare time, she collects shell jewelry, which she admires but never wears. It’s fitting that her earliest memory of jewelry is not just of wearing her mother’s charm bracelet, but of examining the inner workings of a miniature house charm that dangled from it. “It was so precise, and I thought, ‘How could a person do this kind of work?” she recalls. “I was more interested in technique and the craft than by the piece itself.”

“Before you get to my studio, at the front of the street, there’s this light pole. It’s full of morning glories. Full. Up to the wires. It’s morning time and I’m walking my dog; man, these [flwers] are gorgeous. And when I left the studio that day, they were dead. Success, beauty — all of it is temporary. You have these nice, pretty purple plants, right? But they’re dead by the end of the day. In Louisiana, life and death are a part of the culture. We celebrate that,” artist Jammie Holmes tells me, his eyes soft, passionate.

Morning glories are like trumpets in colorful bloom. For me, they recall my Brooklyn childhood, when I watched musicians gather in front of the church’s altar on special occasions, calling upon the instrument’s rich timbre to broadcast, to celebrate God’s presence, to remind us to take note and listen to the Word. This scene is similarly reconstructed in Holmes’ Church Folks exhibition, which dressed the walls of The Gordon Parks Foundation in Pleasantville, New York, with Black women donning Sunday hats and sometimes gold teeth. This memorialization of bodies and objects just before and after church service is “what felt like home,” Holmes explains. After all, “going home” for Black folks in the American South references not only a place of shelter but also what happens when our bodies leave this Earth.

Seeing those morning glories cycle through life and death within hours propelled Holmes toward the flipsideof that exploration: expressions of “being here.” It led him deep into research about the origins of particular flwers, as well as their cyclical phases, and, eventually, to the poetic expressions seen in his most recent show, Morning Thoughts, at Marianne Boesky Gallery in New York. In it, Holmes’ venerated human figues bloom from daylilies and morning glories, referencing the foundational ecology of our world. “At fist, I was not going to put any figues in [the flwers]; it

“The precipice that separates noise from peace A pinch of the ever-evolving magic

A precious place combines and still confirms the space A oneness and togetherness

There’s a morning thought”

– Gil-Scott Heron

was more about the spirit of that plant. I needed somebody to see that spirit.” Holmes shares.

Holmes spends much of his free time at thrift stores, collecting and examining memorabilia from other people’s lives. During one of his visits, he found a photo of a family. In that photo, he saw not only a version of his family and himself but also the plants he cared for in his home. “A lot of me had to become one of the plants,” he explains, threading this association. “When I was painting them, I thought of having faces coming out the inside.” He notes how folks in the South, despite many assumptions, have an incredibly realized connection to the land.

I’m particularly fascinated by Malcolm, a work from the series featuring a boyish face pushing out of a lily. When I ask Holmes about its origins, he reveals, “I have three different Gordon Parks [photographs] in my house, and one of them is a picture with this boy. His back is turned and [he’s standing in front of a street barrier that says] ‘Do not cross.’ This was a kid at one of Malcolm X’s speeches. I did some research and I saw this other photo this other photographer took at the same event, with a group of people. So I used one of the kids from that speech [for Malcolm], because I’m such a fan of the idea of revolution and change.”

Before our conversation, Holmes sent me a video of a woman dissecting America’s regional dialects. As the map moves, so does the texture of her tone as she links certain sections of New Orleans to New York and the Irish migra-

tion, which influened both places. In the deeper South, closer to Thibodaux, Louisiana, where Holmes was born and raised, she explains that French colonization flttened the tongue. I think of her explanation as I hear Holmes speak of his exhibition in New York, his move from Louisiana, his fist ever-visit to an art museum — in Dallas, less than a decade ago. Like language, his story reminds me, art and flwers migrate and pollinate as do people.

By the time this story reaches you, the Morning Thoughts exhibition will have concluded, its works having found new homes all over the world. I ask Holmes how he feels about their scattering.

“With this exhibition, I was getting back to putting myself in the position to ask: What if I was a plant? Since I felt some kind of way about the idea of these things dying so fast. To be able to see the poetry in that, that’s what I specialize in. That’s why I call myself a poet versus anything else. I always quote this Tupac verse, ‘And even as a crack fiend,Mama, You always was a Black queen.’ [Tupac] took something derogatory, then he said, but you’re a Black queen. He uplifted her. That’s how I feel about the people I paint: Even though you’re going through this, you’re going to live forever because I’m going to put you in these places, these spaces so you can live forever. We are not going to forget that y’all existed, that the everyday people existed. I know people who didn’t get a chance to even bloom long enough. So many things are so short-lived.” Words by LaTonya

Maple Candied Pecans

2 cups raw pecan halves

1/2 cup maple syrup

1/2 teaspoon fine sea salt

Sprinkle of ground cayenne (optional)

Sprinkle of cinnamon (optional)

Combine pecans and maple syrup in a cast iron or nonstick pan. Cook over low heat, stirring constantly, until the maple syrup has evaporated and there is no liquid left. Sprinkle mixture with salt and other spices (if desired). Spread on a sheet tray lined with parchment paper and cool completely before serving.

Pigs In a Blanket

2 packs crescent roll dough

1 pack mini hot dogs (halved) or hot dogs (cut into 1-inch pieces and halved)

Cut the dough into rough mini triangles and roll up the hot dog any way you want — each comes out a little different, with its own personality. Bake at 400°F for about 12 minutes, or until golden brown, and serve.

Veggie Christmas Tree

1 lb green beans (washed and trimmed)

1 bunch of broccoli (cut into florets)

1 pint cherry tomatoes

1 piece of yellow pepper (for the star)

Arrange green beans and broccoli into a Christmas Tree shape. Decorate with the cherry tomatoes and cut a star from the yellow pepper to adorn the top. Serve with dip or as is.

The “Death to the Cheese Plate” Cheese Plate

Pick one type of cheese — we chose a beautiful larger cheese that could be cut in half. Arrange it with different crackers or bread and a fun knife or two.

Berry Bowls

Donahue also likes to keep little bowls filled with fresh berries as a light and healthy party snack. She fills many small bowls and places them throughout the space.

Chef Mina Stone and artist Madeline Donahue discuss the everyday art of the holiday table.

I met painter and ceramicist Madeline Donahue at daycare drop-off years ago, when our children were small . I was instantly drawn not only to her but also to her artwork, which depicts often funny, expressive, and uncomfortably intimate portraits of motherhood that felt all too familiar. As our friendship has evolved, I’ve come to understand that Donahue’s work is also a refletion of her life’s philosophy — her way of being in the world. This Texan hospitality and creative sensibility make her an effortless host, who instantly makes you feel at home.