4 minute read

VS Is No BS Considerations for the Current Vesicular Stomatitis Outbreak

By Jacob Hagenmaier DVM, PhD, Production Animal Consultation

When it comes to ruminant diseases that present with vesicular (blister) lesions, foot and mouth disease predominates the conversation nine times out of ten. Foot and mouth disease (FMD) was eradicated from the United States in 1929, hence its designation as a foreign animal disease. Reintro duc tion of the virus would have economically dev astating ramifications for U.S. beef producers as a positive case would likely cause international exports to cease for some undetermined period of time.

Although recent emergency disaster planning has occurred among scientific and regulatory bodies should an FMD threat arise, the risk of cattle operations being affected in the near future remains small. However, another disease with clinical signs closely resembling FMD exists that is not a foreign animal disease and poses significant economic threats to cattle operations: vesicular stomatitis (VS).

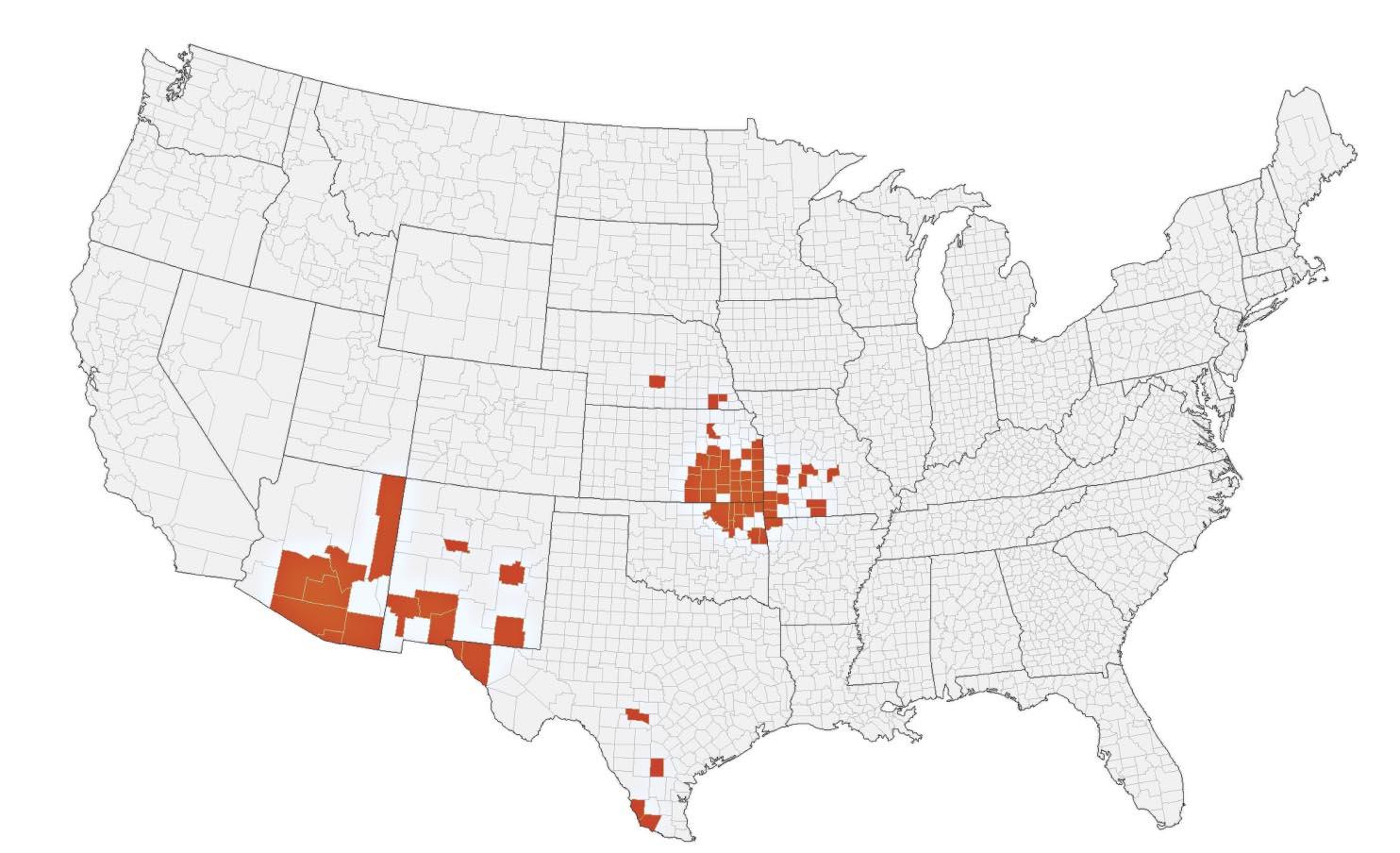

Outbreaks of VS in the United States are most commonly confined to a small number of premises located in southwestern states. Yet, in some years outbreaks can be larger due to transport of infected animals, weather patterns, and transmission pressure of insects. In 2005, a total of 445 premises across 9 states were involved in a severe outbreak that spanned the U.S. from New Mexico to Montana, including 202 positively identified bovine cases. In 2020, VS has certainly garnered more attention due to an ongoing outbreak with confirmed cases in Nebraska, Kansas, Oklahoma, Texas, Missouri, Arkansas, New Mexico, and Arizona, with 12 premises reporting clinically affected bovines (6 in Kansas, 4 in Texas, 2 in Missouri; as of September 3, 2020; Figure 1).

Vesicular stomatitis (VS) is caused by a vesiculovirus of the family Rhabdoviridae. The virus primarily affects horses, cattle, and swine, while sheep and goats are less susceptible and rarely show clinical signs. The virus is most prevalent in and largely considered a disease of the Western Hemisphere, with endemic livestock populations present in Central and South America. Outbreaks of the virus occur via transmucosal spread through direct contact with an infected individual, and transcutaneous spread via arthropod vectors, specifically sand flies, mosquitoes, and black flies. Being an arthropod-borne disease, multi-premise outbreaks follow a seasonal pattern whereby they most often occur during late spring and early summer and the incidence of cases decreases drastically following a frost or end of a rainy season. Having nearby water sources is typically associated with exposure to insects that transmit the virus.

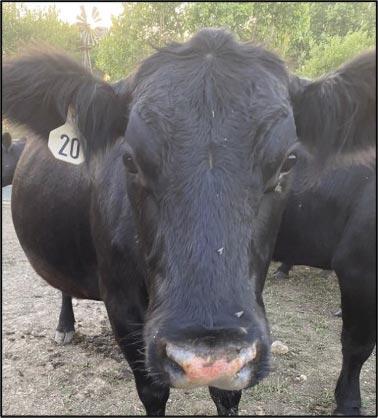

The incubation period, or time from exposure to infection until the animal is showing clinical signs, will typically range between 2 and 8 days, although vesicles can develop as soon as 24 hours post-exposure. The vesicles localize to mucous membranes such as the mouth, mammary gland, coronary band, and interdigital region of the foot in cloven-hoofed animals (Figure 2). Clinical signs reflect the anatomical location of the lesions, with excessive salivation being the most common first sign of morbidity due to the disease. Initially, the lesions may only appear as a blanched area but will progress to raised vesicles that erupt and cause discomfort. Inside the oral cavity, lesions may be present on the lips, tongue, dental pad, or gums. With lesions on the foot, cattle will possess severe lameness and typically large numbers of animals will be affected. Widespread vesicular stomatitis infections in feedyard operations have not been reported, but a reduction in feed intake and an acute spike in feed refusals may be expected to be observed if it were to occur.

Morbidity rates with VS can be very high (90 – 100%), especially in confined settings where transmucosal transmission is likely. Fortunately, the mortality due to the disease is very low as the lesions are self-limiting and most animals are recovered by 14 days following the onset of clinical signs. However, production losses may be significant due to the decreased feed intake and associated weight loss. Treatment for the disease involves supportive care, including feeding of soft feedstuffs to reduce discomfort while feeding, administration of anti-inflammatory drugs to reduce inflammation, and antibiotic therapy for secondary bacterial infections should they occur at the site of the vesicle. Inactivated vaccines conferring immunity against the virus have been experimentally tested in other regions of the world but are not allowed in the United States since cases are rare and vaccination would interfere with diagnostics during an outbreak investigation.

Being a reportable disease, it is critical to contact your veterinarian immediately should you suspect an animal is affected by VS. Until the diagnosis can be confirmed, restricting movement of animals both onto and off the premise is required. Because the lesions of FMD and VS are clinically indistinguishable, it is important to consider whether or not horses on the premise have also been affected, as horses are susceptible to VS but not FMD. Other differential diagnoses for vesicular lesions in cattle include foot rot, infectious bovine rhinotracheitis, and other less common viruses. If confirmed VS, a 14-day quarantine will be placed on the entire premise from the day the lesions appear on the last affected animal. Shared waterers would need to be

Resources

removed and adjacent pens relocated to prevent further transmucosal spread. Gloves should always be worn when handling and examining suspect infected animals as VS is considered mildly zoonotic. In humans, potential clinical signs are similar to the flu such as fever, headache, and muscle aches.

Strategies to mitigate the risk of exposing your horse or livestock to VS involve insect control, minimizing exposure to animals from known infected areas, and preventing noseto-nose contact with potential suspect carriers when at all possible. Horse owners commonly wonder about the risk of contracting the virus at ranch rodeos or other recreational equine events. In such cases, owners can practice caution by quarantining the horses for at least 14 days before being reintroduced to other horses and cattle at the feedyard, on the ranch, or at other events. In addition to the quarantine, minimizing the potential to contract the virus from fomites needs to be a focus by not sharing tack, housing, or feed.

We encourage you to contact your veterinarian and state animal health officials if you have additional questions on the appropriate measures needed to protect your herd or operation from the ongoing outbreak. The USDA APHIS continues to closely monitor the ongoing outbreak of VS in the United States, including the publication of a weekly update that is available to the public, which serves as a good resource to stay up to date with the most recent confirmed VS cases and be aware of the disease pressure in your area.

USDA APHIS Vesicular Stomatitis website: https://www.aphis.usda.gov/aphis/ourfocus/animalhealth/animal-disease-information/cattle-disease-information/vesicular-stomatitis-info

Kansas Department of Agriculture Division of Animal Health, VSV Prevention for Cowboys flyer: https://agriculture.ks.gov/docs/default-source/ah---disease-control/vsv-flyer-for-cowboys_email.pdf?sfvrsn=6e3d8dc1_4