14 minute read

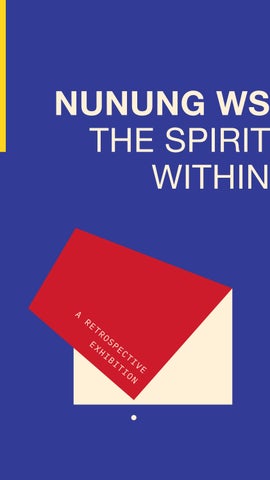

THE SPI RIT WIT HIN

A Curatorial Introduction to Nunung WS Retrospective Exhibition

National Gallery of Indonesia

Advertisement

by CHABIB DUTA HAPSORO

NUNUNG WS is a name that stands for consistency, endurance, and energy in Indonesian abstract painting. Born Siti Nurbaya, she took the name Nunung—which was her childhood nickname—and took WS, an abbreviation of Wachid Sa’ad, the name of her father whom she always respected. Nunung’s career spans from the early 1970s to this very day. She has made hundreds of paintings. In addition to consistency, she has explored several styles.

The Spirit Within is a retrospective exhibition by Nunung WS. The exhibition is not all about Nunung’s previous works, which might suggest that the end of her career is in sight. Instead, the exhibition includes many of Nunung’s most recent works, which were created between 2020 and 2023. Nonetheless, they still represent the important peaks or bodies of her work.

Nunung Ws In Three Periods Of Work

If we line them up, Nunung’s bodies of work cover three periods: The first is the artistic manifestation of Nunung’s perception of nature around her. When Nunung was at the peak of her indecision and dissatisfaction with the art education process at Akademi Seni Rupa Surabaya (Aksera)—where she studied, an opportunity brought her to Jakarta. It was during an exhibition of her class in 1971 at the Cipta Gallery, Taman Ismail Marzuki, Jakarta. On this occasion,

Nunung encountered Nashar for the first time, who praised her works that were on display. Nunung had been admiring Nashar’s works for a long time. Long story short, Nunung took this opportunity to pursue art under Nashar’s guidance: she often spent months living in Jakarta where she painted under the mentorship of the Padang Pariaman-born painter. There are several reasons that made her feel comfortable and at ease when learning directly from Nashar. One of them is that Nashar saw her as an equal partner and was not awkward about the fact that Nunung is a woman.1

Under the mentorship of Nashar, her awareness of painting began to shift from where it had been before. The objects and scenery around her began to be manifested in a number of free simplifications, even violating the rules of figurative (non-technical) form and anatomy, as well as compositions in the field of bold pastel colors.

However, the image in the painting was not present in Nunung’s drawings. She was more expressive and efficient in managing Chinese ink, charcoal, and watercolor or acrylic on paper. Many of her drawings took shape with breathless pulls of watercolor with a palette of colors such as blue, yellow, and light pink mixed with strokes of charcoal. Nunung depicted more “arbitrarily” the objects that stirred her heart. In this period, we find titles of works that refer to typical locations such as Bali, Maninjau, and Borobudur.

Nunung’s works of this period exhibit what art critic Sanento

Yuliman called lyricism. According to Yuliman, many Indonesian painters embodied a lyrical experience of nature or life “without painting objects in nature itself.”2 Although we can still see and sense the shape of the hills in Maninjau by Nunung on several occasions, the realistic image of the Maninjau valley was absent from Nunung’s works, especially since there was no sense of reference to the horizon. There was no illusion that depicting the real world in these works, but rather “irregularities and variations in shapes, which show a form that has its prototype in nature” to “express the artist’s emotions and feelings in experiencing the world.”3 This lyricism, as Yuliman mentioned it, marks the Third Period abstract painting that many Indonesian painters have been working on since the late 1960s.

The mentor, Nashar, has a unique understanding as a painter regarding the connection between humans and nature. Nashar always tried to “unite with nature,” which he elaborated with the phrase “I look at a chair, I feel it until the realization comes to me that I am the chair itself.”4 For Nunung, the principle of painting comes through her awareness of not relying too much on her sense of sight. Instead, she was told by Nashar to feel the wind, smell the scents, and so on, and harness her intuition as much as possible.

Through his words, Nashar wanted to state that humans are supposed to be part of nature and not the other way around, with nature being the entity that humans objectify. Due to certain conditions, the human mind or spirit might also be out of sync with the rhythms of nature. We can underline that the period under Nashar’s mentorship was a time when Nunung worked on refining her sensory sensibilities, to establish and harmonize her spirit with all the sensations and rhythms of nature.

In terms of how artists immerse themselves in nature, Bali holds an important place for Nunung, who was also inspired by Nashar.

Nunung once mentioned that Bali was a “paradise” for her eyes and mind which made it easier for her to appreciate and thus be one with nature. Nunung spent several long periods of time in Bali along with Nashar to paint at least in the mid-1970s and 1980s. For Nunung, Bali also offers a holistic way of life where spiritual life is inseparable from the mundane or profane world. Therefore, Nunung is always amazed when seeing ceremonies because in them “there are colors, dance movements, the sound of gending and music become one.”5

Indeed, Bali has fascinated not only Nunung and Nashar but also foreign and local painters before and after them. These interests were more or less influenced or even shaped by the romanticization and imagination of Bali through the paintings of European painters who settled in Bali during the colonial period, especially in the nineteenth to twentieth centuries. In retrospect, however, it seemed that Nashar was trying not to repeat the touristic idealization of the European painters. In his journal, he once lived in a poor village to experience Balinese life in a more real way outside of these imaginings.6 In a similar way, Nunung’s artistic life in Bali was humble, even bohemian as she often only stayed in shelters or rented houses in Bali.

The second phase of Nunung’s work developed around gestural expression, which was reflected in increasingly expressive and vibrant brushstrokes. She explored this very intensively in the period from the late 1980s to the early 1990s. During this period, Nunung’s appreciation of the objects and nature around her deepened, which in manifestation became more distant from the forms or figures she saw in nature. Instead, Nunung’s sense of nature and life around her grew more and more intense.

Nunung has also become more obsessed with color. Her color palette has also become more diverse. Her perception of the color showed how color merged with her or became an extension of her senses or herself. Therefore, color becomes a medium for lyrical expression, as she stated, “Color is not there as color, but it is there as an expression as well as an embodiment of deep personal feelings.”7

While exploring these gestural expressions, Nunung also emulated the typical expressiveness of calligraphy, not only Arabic calligraphy but also Japanese and Chinese. These calligraphic expressions even led Nunung to seek spiritual experiences. The distinctive lines (khat) of calligraphy inspired Nunung to create a series of works with strokes that are expressive and lively, yet efficient and quiet.

The desire of artists to seek and experience spiritual power was prevalent during the 1970s and 1980s. This desire was also inseparable from the artists’ longing for the traditional culture from which they came or did not come. One reason for this tendency was that modern life or social order had taken away or replaced the holistic traditional way of life. Modern life, as forcibly introduced by colonialism, separates the spiritual from the everyday. This has left modern Indonesians in limbo.

The distance of Indonesian artists from spiritual-traditional matters has given artists and poets the motivation to return to it.

Author and scholar Abdul Hadi WM

elaborated on three motivations for Indonesian artists and writers to approach and re-address tradition during the 1970s and 1980s. The first is the adaptation of traditional cultural elements in order to innovate their style of expression. Artists with this tendency see tradition as an element that is relevant to the contemporary world. Secondly, adapting certain regional cultures such as Java, Minangkabau, Malay Riau, and others to give a distinctive style to Indonesian art. Thirdly, to adapt certain spiritual and religious aspects by realizing that the traditional culture of Indonesian society is enriched by major religions and beliefs.8 Of these three motives that Abdul Hadi suggested, the first and third are more likely to be Nunung’s tendencies.

Although Nunung might be less described as a tradition-inspired artist, her family’s strong Islamic background has shaped her along with the Javanese traditions that have been closely intertwined with the distinctive Islam. Growing up under the roof of the Islamic “santri” community, she formed a strong religious foundation and mindset. Moreover, this traditional Islamic setting also gave Nunung a specific spiritual experience, which led her to constantly seek further spiritual experiences through the practice of painting.

Indeed, Nunung’s adoration of calligraphy did not lead to the appearance of calligraphic writing in her paintings. Nunung did not fall into the trap of creating calligraphy—especially Islam—that only led to statements of doctrine and theology. Instead, Nunung was probably more eager to understand what Abdul Hadi referred to as Islam, which became an integral part of the development of the traditions and civilization of the archipelago that shaped its belief system, rituals, and forms of spirituality.9 Nunung fulfilled one of the Islamic aesthetic ideas of Abdul Hadi WM, that, “Art is an attempt to transform ideas and spiritual experiences into aesthetic objects, rather than transforming objects outside of oneself that are reached by sensory vision.”10 Through this period, Nunung’s artistic expression has advanced a step from where it was in the previous period.

Furthermore, it was reaffirmed that the development of Nunung

WS practice was recognized as an innovation inspired by a spiritual quest that was inseparable from the traditional life that had been intertwined with Islamic influences. Nunung’s spiritual pursuit shows the inseparability of spirituality and traditional culture. This is highlighted by A.K. Comaraswamy, a philosopher who said tradition always leads to the original and is always able to realize the aesthetic expression of inspiration or contemplation that comes from a transcendent source.11

The gestural expressions of calligraphy led Nunung to a third period of her work, which drew her deeper into the search for a spiritual atmosphere. This third period took place from the mid1990s to this day.

It is safe to say that Nunung’s expression modeled on gestural calligraphy did not last beyond the mid-1990s. She discovered a different style of expression that allowed her to connect to spiritual experiences in another way. She started to develop her color fields and stacks. The fundamental difference from his previous expression is that in this period Nunung spent a lot of time contemplating and designing before the work was executed. In the previous abstract gestural period, Nunung relied more on spontaneity and intuition. In this period Nunung’s paintings come with an efficient color palette.

During this third period, Nunung’s strokes became more plane-shaped with a carefully crafted color palette. They were layered with borderlines that suggested a threshold atmosphere. Another significant step she took was to embed concrete objects in her paintings, such as transparent paper. This transparent paper dampens the intensity of the colors in the layered shapes, giving a dim sensation. The concrete nuance was also presented by Nunung through the papers that were folded in several ways. The concrete objects and visual sensations achieved through these non-painting attempts have presented a rich yet thrilling “nuances of abstraction”. This style of expression showed the breadth of Nunung’s sources of inspiration. The transparent and dim nuances derived from the visual sensations Nunung saw and the intricate intertwining of threads in her father’s sarong or the woven fabric of Nusantara. The folds in her paintings came from Nunung’s childhood memories of folding paper.

This style of expression showed the broadness of Nunung’s sources of inspiration. The transparent nuance is delivered through the rich visual sensation of the intricate intertwining of threads in her father’s sarong or the woven fabric of the Nusantara. The folds in her paintings came from Nunung’s childhood memories of playing and folding paper.

This proved that Nunung’s search for the spiritual always stemmed from the dynamic, everyday reality of the material world. Mediated by typical painting practices, Nunung has attained a mystical experience. It would be no exaggeration if art critic Carla Bianpoen once referred to her as a pilgrim in the Holy Land through her art practice.12

We can also underline that Nunung WS’s art practice is a cycle. Nunung constantly revisits and remixes her previous achievements with renewed awareness. This leads to new branches that open up many possibilities. This approach is what makes Nunung’s bodies of work distinctive: there is always a pattern or order in the way she draws lines, uses materials, colors, and so on. We are dealing with an organized and measured development of her work.

Nunung Ws In The Middle Of The Indonesian Art Scene

In her quest for maturity as an artist and a human being, Nunung is indeed driven by spiritual forces. Painting is her method of meditating and contemplating to reach the level of spirituality in order to achieve a unity of the spirit within transcendent substances. It is an endeavor that requires a lifetime of commitment. Nunung’s commitment has not been unchallenged, given that she is a female Indonesian artist in the midst of the art scene and living structures that were still shackled by patriarchy, especially during the New Order era.

The 1980s and 1990s were a period when Nunung WS became very involved in her work. She held many exhibitions, both at home and abroad. Nunung also frequently went on trips and art residencies and received a number of awards. This situation appeared to be an anomaly, considering that the New Order restricted the position of women in many fields, including in the arts. Gender activist Julia Suryakusuma has said that the repression of women during the New Order was in the form of the idealization of certain roles of women that trapped them in the domestic sphere.13

In terms of art, Carla Bianpoen and artist Mella Jaarsma stated that women artists were rarely involved in large-scale or mainstream art exhibitions in the 1980s and 1990s. In their opinion, this was due to the stereotypes of the dominant art actors, male artists, who believed that women were less qualified or less motivated to make art, and thus deserved to be referred to as part-time or Sunday artists.14

Bianpoen and Jaarsma show the cause of this stereotype with the heart-breaking facts that happened to a number of Indonesian women artists once they married into the profession. Their painting and art activities were hindered by their domestic roles as wives and mothers, which reflected the ego of the husbands who were also artists.15

Nunung admitted that she felt lucky to have a family that upholds equality in the distribution of household duties. In front of her future husband, Nunung, who has long vowed to be a painter, assertively stated that whatever decision she makes in life, including getting married, giving birth, and raising children, should not prevent her from continuously painting. And neither would Nunung prevent her future husband from painting. Nunung and Sulebar Sukarman, her then-husband, were married in 1978 and had a son named Seno Ahmad in 1979. They continued to honor their commitments as a couple until Sulebar passed away in May 2022.16

Despite the amount of freedom, Nunung was not in a comfortable position. She realized that there was still an imbalance in the opportunities Indonesian women artists had to work and to make exhibitions. Together with a group of fellow female artists, she founded the Nuansa Indonesia collective in 1985. She then served as the group’s secretary. The Nuansa Indonesia collective’s articles stated that the group aimed to advocate for the position of Indonesian women artists while simultaneously upholding the dignity of Indonesian art as a profession.17

Nuansa Indonesia has held a number of exhibitions, including collaborations with female artists in Malaysia. But activities of the collective declined and ceased in the mid-1990s.

Nevertheless, Nunung has been working to this day with all the expectations and challenges she has faced. That’s why artist Teguh Ostenrik once called Nunung a woman who has never failed to liberate herself from the conventional norms of life.18

End Notes

1) Carla Bianpoen and Mella Jaarsma, “Perempuan Perupa: Antara Visi dan Ilusi”, in Perempuan Indonesia, Dulu dan Kini, Mayling Oey-Gardiner Mildred L.E. Wagemann, Evelyn Suleeman, Sulastri (eds.). (Jakarta: Gramedia Pustaka Utama, 1996), p. 87.

2) Sanento Yuliman, Seni Lukis Indonesia Baru: Sebuah Pengantar (Jakarta: Jakarta Arts Council, 1975), p. 37.

3) Ibid. hlm. 37, 40.

4) Nashar, “Surat Ketiga Belas”, in Nashar by Nashar (Yogyakarta: Yayasan Bentang Budaya, 2002), p. 273.

5) An interview with Nunung WS on May 17, 2023.

6) Nashar, op. cit. p. 147, 151.

7) Nunung WS, “Wawasan berkarya”, in Katalog Pameran Tunggal Nunung WS in Taman Ismail Marzuki, Dewan Kesenian Jakarta, December, 6-14 1989.

8) Abdul Hadi WM, “Kembali ke Akar, Kembali ke Sumber”, in Kembali ke Akar Kembali ke Sumber: Esai-esai Sastra Profetik dan Sufistik Dr. Abdul Hadi WM, Ali Akbar (ed.) (Jakarta: Penerbit Pustaka Firdaus, 1999), p 6.

9) Ibid. hlm. 13.

10) Ray Livingstone, The Traditional Theory of Literature (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1962), hlm. 15-17.

11) Ray Livingstone, The Traditional Theory of Literature (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1962), hlm. 15-17.

12) Carla Bianpoen, “A Pilgrim to Holy Land”, The Sunday Observer, 26 Oktober 1997.

13) Julia Suryakusuma, Ibuisme Negara: Konstruksi Sosial Keperempuanan Orde Baru (Jakarta: Komunitas Bambu, 2011), p. 18-19.

14) Bianpoen and Jaarsma op. cit. p. 74.

15) Bianpoen and Jaarsma op. cit. p. 80.

16) An interview with Nunung WS on May 17, 2023.

17) Sanento Yuliman, “Wanita Indonesia dan Seni Lukis” in Nuansa: Pameran Seni Lukis Wanita Indonesia-Malaysia the exhibition catalog, 1991

18) Teguh Ostenrik, Women Artists: Between Vision and Illusion, p. 89.

NUNUNG WS is an abstract artist with a career spanning over half a century. Despite receiving family pressure to study religion, her passion for the arts appeared at an early stage. In particular, she was inspired by Kartika Affandi, the artist daughter of Kusuma Affandi, who served as a role model that women too could succeed in art. Under the guidance of Nashar, Nunung transitioned from the dynamic expressionism of Kartika and her father to more reflective studies, juxtaposing planes of color that are both meditative and jewel-like. She is a masterful and subtle colorist, using luminous hues to create artwork that stimulates and mirrors the subconscious’s dreams and emotions. Their beauty and power quickly earned her acclaim, as well as national and international group and solo exhibitions.

Nunung tries to re-create what she sees, experiences, lives, and feels in nature through color because colors always attract her attention. Therefore, while painting, she is not bound into shapes because it will only limit her work. Instead, she tries to go deep through total comprehension and the abstraction of forms to express her work solely by using colors she wanted freely. For Nunung, The art of abstract is a transcendent journey-a spiritual journey. Three crucial factors describe her artistic journey, which is: magic, mystical, and religion. She believes that these three factors emerge as we start to drift away from our traditional and cultural beliefs and helps us create an even stronger bond as we try to push it away or forget it. She described the balancing of life as an interpretation of ‘soulscape,’ the major theme of her painting. She takes what she sees and refracts it through contemplation and her inner spiritual lens to express life through color and shape.

Nunung has been active in the Indonesian art scene and has held exhibitions since the 1970s,in Indonesia and overseas. The education she received from her Islamic family has made her a strong woman, and her independent demeanor can be seen through her paintings. She chose to pursue abstraction because she wants to invite her observers to not only enjoy her work visually but also to understand what goes on during the process of creating her masterpieces.