5 minute read

Better Light and Better Sleep

By Jennifer Brons 1 and Mary Beth Gotti 2

1 Light and Health Research Center at Mount Sinai, 2 American Lighting Association

Ninety years ago, the Illuminating Engineering Society (IES) and its members, manufacturers, and utilities embarked on a collective marketing campaign called “Better Light, Better Sight.” That campaign helped assure the public that a given light fixture would provide good visibility without glare.

“Better Light, Better Sight” fixtures were differentiated in lighting showrooms with a hangtag. The public readily embraced this program’s message, benefiting manufacturers who wanted to sell higher quality lighting as well as utilities who wanted to increase electric load (at that time) by encouraging the public to use more incandescent light bulbs.

Importantly, rather than being a hollow marketing gimmick, the “Better Light, Better Sight” program acknowledged only those fixtures that met objective measurement criteria, and those fixtures were the only ones allowed to use the hangtag.

We now know that light isn’t just for vision anymore.1, 2 Rather, light received at the eyes is the primary stimulus for synchronizing our circadian system to local time, including orchestrating when we sleep, how quickly we fall asleep, and how well we sleep.

Taking the cue from the IES campaign, the American Lighting Association (ALA) investigated the potential benefits of the latest research by funding a Better Light, Better Sleep project at the Light and Health Research Center, the results of which might be used to promote better sleep with residential lighting.

Residential lighting is particularly relevant for regulating circadian rhythms because most of us are at home during the most important times for the circadian system.

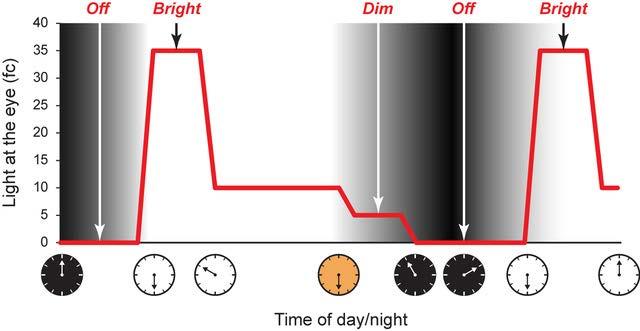

Morning and evening light have the greatest leverage during our waking hours for affecting the timing of circadian rhythms (Figure 1). Bright morning light following nocturnal sleep is the most effective for entraining the circadian system to our diurnal behavior and physiology.

Bright evening light can upset that timing. Evening light should be dim, but not so dim that it compromises safety or comfort. (Light of medium brightness can be employed through the late morning and afternoon as an option, but the light levels recommended for the early morning and evening are crucial.)

Thus, it could be argued that residential lighting is the most important lighting for supporting circadian entrainment and good sleep.

Importantly, some forward-thinking members of ALA participated in the project by submitting prototype products to be evaluated. Similar to the early IES’s “Better Light, Better Sight” program, the Better Light, Better Sleep project established four simple performance criteria that could be objectively tested:

• A control that provided daytime (bright), evening (dim), and nighttime (off) settings

• A daytime illuminance of 35 foot-candles (fc) at the eyes

• No more than 5 fc at the eyes during the evening

• A luminance not to exceed 8,500 candela/m2 to minimize discomfort glare.

To meet the Better Light, Better Sleep criteria, the participating manufacturers also had to define the use case for their product. Eight manufacturers supplied products for consideration.

Frankly, the submissions were amazing. Initially, we thought we would get a lot of desk light prototypes, but those we received were in the minority. We also received, as two outstanding examples, an array of six small downlights in the ceiling plane and an entire family of tabletop and floor fixtures to populate a comfortable living room. Impressive.

A few of the prototypes we tested met all the criteria on their first try, and several would have passed with adjustments in position or output. The most challenging criterion was luminance, largely because none of the manufacturers were equipped with a luminance meter.

We suggested, rather than buy a luminance meter, they make a visual comparison to something that would not evoke discomfort glare. As a broad guideline, we pointed out that the brightness should be no greater than the luminance of a T-12 fluorescent lamp or that of the north sky on a clear day, neither of which cause objectionable discomfort glare.

It is probably fair to say that a typical manufacturer of residential lighting fixtures focuses mainly on style and aesthetics without paying much attention to the impact of light on sleep. However, the Better Light, Better Sleep project has shown that it is possible for lighting fixture manufacturers to go beyond style and aesthetics, incorporating the science of sleep into their product offerings and thereby adding value.

Perhaps, one day, circadian-effective lighting will have a place in society alongside those other two pillars of health, diet and exercise (Figure 2). To do so, we will need attractive and affordable luminaires that can also deliver better light for better sleep.

References

1 Rea MS. Light for the circadian system: Beans or chili? designing lighting. Feb/Mar ed. Brentwood, TN: Edison Report, 2023.

2 Figueiro MG, Nagare R, Price LLA. Non-visual effects of light: How to use light to promote circadian entrainment and elicit alertness. Lighting Research and Technology 2018; 50: 38-62.