4 minute read

city of a thousand courtyards

circularity: from voids to obsolescence

m.arch 2 arch 675: urban systems instructors: dr. brian sinclair and alberto de salvatierra The approach for this manifesto comes in a two part thesis: the first being about the senseless division between what is necessary and what is desired in urbanization, and the second being what happens to that which is undesirable in our cities. These two topics both play a large role in circular design, and have significantly shaped my mindset around the idea of intentionality in design and considering the consequences of our designs through their entire life-cycle. I am often struck by the stark physical division between infrastructure and people. We go to great lengths to hide essential services - power lines, communication towers, electrical conduits, plumbing, sewage - underground and out of sight, and build rail yards, factories and other industrial spaces in the fringes of our cities. This has always seemed counterproductive to me, as these services are necessary for the development of urban centres, yet we do everything we can to exclude them from the urban fabric. These industrial spaces and objects are considered eyesores, and as cities expand around them, they become undesirable voids that businesses and residences have traditionally avoided. These voids perpetrate harmful phenomena such as urban sprawl and planned obsolescence in technology, each a manifestation of the human tendency to avoid and discard that which is undesirable. Yet, we cannot deny that these services and processes are necessary to urbanization; while we may be able to invent a more beautiful, efficient or desirable way to carry out these processes, in most cases we do not have the time or capital to do so. Thus, we are left with undesirable technology powering the advancement of our cities, but not participating in the city itself. We are in the midst of an extremely exciting and unprecedented period of advancement, one that I think will continue to flourish increasingly rapidly. We live in an age where as soon as one thing is created it expires and a new, better version must be created. Each upgrade to our systems and technologies is replaced increasingly quickly with a new and improved version, creating an insatiable cycle of frenzied iteration and production. Growth begets growth. Humans have an extraordinary gift in being such an intelligent species, capable of innovation and conscientiousness that allow us to continue to make advancements exponentially. But I also think that it is this capability to advance at astronomical rates that will be our downfall if we let it continue unhindered by reality. As a species with such tremendous intelligence, we have an obligation to our future generations and to our planet to conduct our growth as sustainably as possible, an obligation which we are currently failing. Cities grow in size and complexity far faster than anyone can control, yet their growth is powered by those who cannot control it. I do not believe in halting our growth, but rather ensuring that growth is limited to that which is necessary, and is not just a product of progress for the sake of progress. Growth can mean improving what already exists and filling the voids that exist in our cities. Fully integrated urban centers would not leave their undesirable networks to the fringes. These essential pieces of infrastructure would not only be integrated into the urban fabric, but welcomed and loved for what they provide to our cities. Instances of this are beginning to take shape in some pockets of our cities. Projects such as the High Line in New York City, which took an obsolete railway track and turned it into a public park, show us that all that is needed to meet these circular demands for sustainability is a positive reframing of what these things could be. By embracing what we already have or repurposing it so it can continue to contribute to society, we can reduce our waste and our impact on the planet, while allowing for more meaningful urbanization and growth.

Advertisement

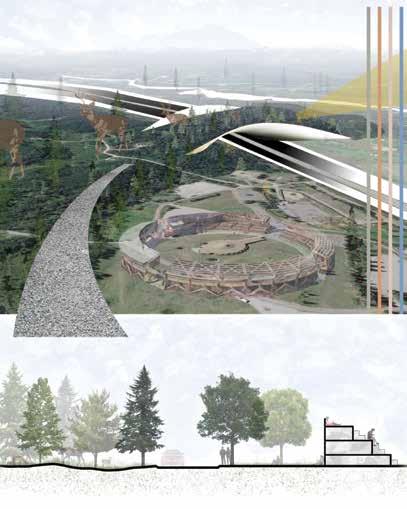

nisk’a-hi

nathan stelfox mitchell stykalo

m.plan 2 plan 616: urban design studio instructors: dr. fabian neuhaus and hal eagletail Nisk’a-hi, meaning about the land, was conceived from a process of ethical engagement and understanding of Tsuut’ina culture. Being about the land means transcending boundaries of western thought in an attempt to design as stewards, not users. Respecting the culture, people, and land of the Tsuut’ina Peoples was key in developing a vision for two distinct 2. FOOTHILLS SECTION + ATMOSPHERE COLLAGE communities. Foothills to the West and Grasslands to the East are not just places for people, but represent an all encompassing design that prioritizes the natural environment. These places do not create boundaries, rather, they connect natural flows and people.