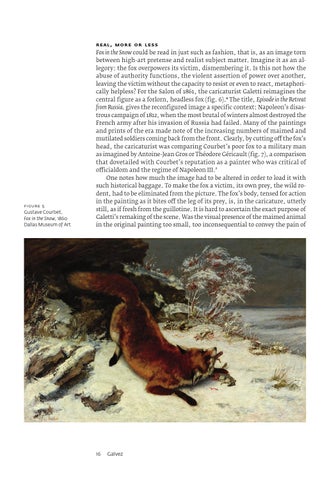

figure 5 Gustave Courbet, Fox in the Snow, 1860 Dallas Museum of Art

real, more or less Fox in the Snow could be read in just such as fashion, that is, as an image torn between high-art pretense and realist subject matter. Imagine it as an allegory: the fox overpowers its victim, dismembering it. Is this not how the abuse of authority functions, the violent assertion of power over another, leaving the victim without the capacity to resist or even to react, metaphorically helpless? For the Salon of 1861, the caricaturist Galetti reimagines the central figure as a forlorn, headless fox (fig. 6).6 The title, Episode in the Retreat from Russia, gives the reconfigured image a specific context: Napoleon’s disastrous campaign of 1812, when the most brutal of winters almost destroyed the French army after his invasion of Russia had failed. Many of the paintings and prints of the era made note of the increasing numbers of maimed and mutilated soldiers coming back from the front. Clearly, by cutting off the fox’s head, the caricaturist was comparing Courbet’s poor fox to a military man as imagined by Antoine-Jean Gros or Théodore Géricault (fig. 7), a comparison that dovetailed with Courbet’s reputation as a painter who was critical of officialdom and the regime of Napoleon III.7 One notes how much the image had to be altered in order to load it with such historical baggage. To make the fox a victim, its own prey, the wild rodent, had to be eliminated from the picture. The fox’s body, tensed for action in the painting as it bites off the leg of its prey, is, in the caricature, utterly still, as if fresh from the guillotine. It is hard to ascertain the exact purpose of Galetti’s remaking of the scene. Was the visual presence of the maimed animal in the original painting too small, too inconsequential to convey the pain of

figure 6 Galetti, Episode in the Retreat from Russia, 1861

victimhood so vividly displayed by the solitary headless fox in the drawing? Or was the caricaturist perhaps mocking Courbet, saying, essentially, that no matter how delicately rendered an animal’s fur, it nonetheless comes across to the viewer as something dead, lifeless — beheaded, so to speak — and thus unequal to the miraculous re-creation of lifelike human figures that for so long had been the glory of Western mimetic representation? There is another way to read the painting’s realism. In 1859, writing to his compatriot-in-exile Max Buchon, Courbet mentions in passing the recent receipt of Champfleury’s short story “The Wax-Figure Man.”8 At first glance, figure 7 Théodore Géricault, Return from Russia, 1818 Yale University Art Gallery, New Haven

16

Galvez

Courbet

17