C&T

Issue 312 | September 2023

PUBLISHER

Centre for Veterinary Education

Veterinary Science Conference Centre

Regimental Drive

The University of Sydney NSW 2006 + 61 2 9351 7979 cve.publications@sydney.edu.au cve.edu.au

Print Post Approval No. 10005007

DIRECTOR

Dr Simone Maher

EDITOR

Lis Churchward elisabeth.churchward@sydney.edu.au

EDITORIAL ASSISTANT

Dr Jo Krockenberger joanne.krockenberger@sydney.edu.au

VETERINARY EDITOR

Dr Richard Malik

DESIGNER

Samin Mirgheshmi

ADVERTISING

Lis Churchward elisabeth.churchward@sydney.edu.au

To integrate your brand with C&T in print and digital and to discuss new business opportunities, please contact:

MARKETING AND SALES MANAGER

DISCLAIMER

All content made available in the Control & Therapy (including articles and videos) may be used by readers (You or Your) for educational purposes only.

Knowledge and best practice in this field are constantly changing. As new research and experience broadens our knowledge, changes in practice, treatment and drug therapy may become necessary or appropriate. You are advised to check the most current information provided (1) on procedures featured or (2) by the manufacturer of each product to be administered, to verify the recommended dose or formula, the method and duration of administration, and contraindications.

To the extent permitted by law You acknowledge and agree that:

I. Except for any non-excludable obligations, We give no warranty (express or implied) or guarantee that the content is current, or fit for any use whatsoever. All such information, services and materials are provided ‘as is’ and ‘as available’ without warranty of any kind.

II. All conditions, warranties, guarantees, rights, remedies, liabilities or other terms that may be implied or conferred by statute, custom or the general law that impose any liability or obligation on the University (We) in relation to the educational services We provide to You are expressly excluded; and

III. We have no liability to You or anyone else (including in negligence) for any type of loss, however incurred, in connection with Your use or reliance on the content, including (without limitation) loss of profits, loss of revenue, loss of goodwill, loss of customers, loss of or damage to reputation, loss of capital, downtime costs, loss under or in relation to any other contract, loss of data, loss of use of data or any direct, indirect, economic, special or consequential loss, harm, damage, cost or expense (including legal fees).

Established in 1969, this unique veterinary publication celebrates over 50 years of veterinary altruism. An ever-evolving forum gives a ‘voice’ to the profession and everyone interested in animal welfare. You don’t have to be a CVE Member to contribute an article to the C&T Series. Send your submissions to Dr Jo Krockenberger: joanne.krockenberger@sydney.edu.au

"I enjoy reading the C&T more than any other veterinary publication."

Terry King Veterinary Specialist Services, QLDThe C&T Series thrives due to your generosity. If you’re reading this and have been contemplating sending us an article, a reply or comment on a previous C&T, or would like to send us a 'What's YOUR Diagnosis?' image and question or seek feedback from colleagues, please don’t hesitate to contact us.

The C&T is not a peer reviewed journal. We are keen on publishing short pithy practical articles (a simple paragraph is fine) that our readers can immediately relate to and utilise. And the English and grammar do not have to be perfect—our editors will assist with that.

C&T authors agree that it is extremely satisfying to read their articles in print (and the digital versions) and know they are contributing to veterinary knowledge and animal welfare.

It was with some trepidation post covid that the CVE ventured back into the world of face-to-face events, not knowing how enthusiastic people would be to gather in groups. As I write, we are in our busiest period for in-person events, and it has been absolutely fantastic.

There is really nothing like gathering with a group of colleagues, catching up with those you haven’t seen for a while or making new friends, identifying with shared challenges, and connecting across a broad range of experiences. That said, we realise that not everyone has the capacity to attend in-person offerings and we remain committed to making education accessible through virtual programs, our open-access WebinarLIVE! series and of course, the C&T.

In this edition, I was fascinated to read Peter Irwin and John Beadle’s submission on canine ehrlichiosis. For a disease that remained exotic to Australia for so long to now be considered endemic is sobering. This article provides a must-read summary of what to be alert to in both presentation and clinical history.

Speaking of evolving, Imogene Ewen and Sally Coggins’ case study describing the dissolution of an atrial thrombus in a cat using antithrombotic therapy is at the cutting edge of medical treatment.

If dogs and cats aren’t your regular patients, make sure you read John Dooley’s account of treating peritonitis in a dairy cow, or Olivia Clarke’s excellent summary of dental disease in rabbits. There really is something for everyone in this edition!

Happy reading!

t. +61 8 9360 2590 |

e. p.irwin@murdoch.edu.au John Beadle Veterinarian & Practice Owner All Creatures Veterinary Hospital, Broomet. +61 8 9192 8081

C&T No. 5981

Peter has been studying tick-borne diseases of companion animals and wildlife for over 30 years.

In May 2020, in Kununurra, northern Western Australia (WA), dogs with significant fever, malaise, and haemorrhagic diatheses were diagnosed with ehrlichiosis, sparking a veterinary biosecurity alert. Despite its designation as a notifiable disease, with movement restrictions for dogs in northern Australia and the unfolding COVID-19 pandemic during 2020 (that supposedly imposed travel limitations on the dog owning public), CME was soon observed throughout most of northern WA and the Northern Territory. High morbidity and mortalities were reported, especially among dogs at indigenous communities.

Canine monocytic ehrlichiosis (CME) is a tick-transmitted disease of domestic dogs and wild canids caused by Ehrlichia canis (E. canis), a Gram-negative, intracellular bacterium belonging to the family Anaplasmataceae.¹ The organism was first described in dogs in Algeria,² and later came to prominence during the Vietnam War in the 196070’s when scores of military working dogs died of what was then referred to as ‘tropical canine pancytopenia’.³ Today, CME is recognised as a serious illness affecting dogs in tropical and subtropical regions of the world with the exception, until recently, of Australia.

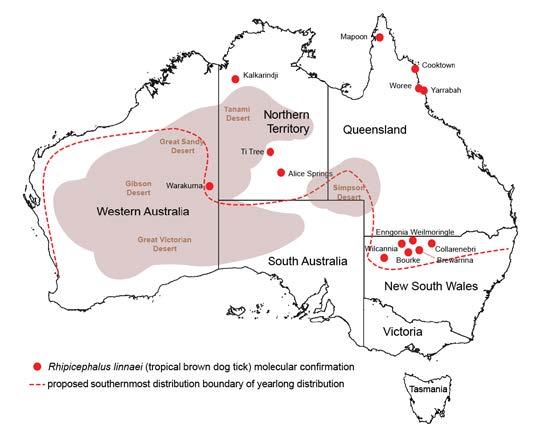

The biological and clinical features of E. canis infection have been studied extensively (outside Australia). The vector is the brown dog tick Rhipicephalus linnaei (the new name for Rhipicephalus sanguineus ‘tropical strain’).⁴ This tick occurs in warm and humid climates worldwide, including northern and central Australia, and is well adapted to survival in dwellings and kennel environments.⁵

Transmission of E. canis to the dog occurs rapidly, within 3 hours of female tick attachment,⁶ and probably even faster from male ticks as they ‘graze’ on the host while

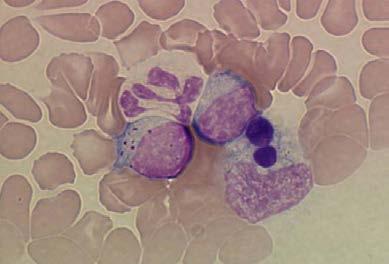

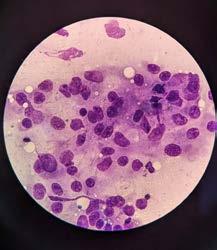

crawling around looking for females.⁷ Clinical signs develop 8-20 days after infection and intracytoplasmic inclusions (morulae) may be observed at this stage in circulating monocytes (Figure 1).⁸

It is known from experimental studies that E. canis infection typically progresses through acute, subclinical, and chronic (terminal) phases;⁸ however, the timing of these stages is variable and unpredictable. Typical clinical signs reported globally include lethargy, weakness, decreased appetite or anorexia, fever, pale membranes, panting, bleeding diathesis, lymphadenomegaly, hepatosplenomegaly, and dehydration.8,9

The clinical picture of CME in Australia seems to have changed over the last three years. Originally, during 2020-2021, as CME established, a severe clinical syndrome was encountered in northern Australia, notably within indigenous communities. Epistaxis was often profound (Figure 2a) and life-threatening, and body temperatures as high as 41.5°C were not uncommon. Some dogs presented with dyspnoea and fever, but no bleeding, and in others cachexia was often rapid in onset. Dogs with pancytopenia rapidly progressed to sepsis and uncontrollable bleeding within a few days, and some dogs presented with blindness due to retinal haemorrhages. Another group developed generalised dependant oedema months after the acute illness, characterised by marked swelling of the face, neck and limbs (Figure 2b) and occasionally the scrotum (Figure 2c)

Now, three years on, observations by vets diagnosing CME describe a more nuanced clinical picture in endemic areas, although the severe signs persist sporadically. This is more in line with reports from overseas where CME

has achieved a level of endemic stability. Vets working in the north are reporting that some dogs which are clinically normal (therefore no suspicion of CME) develop complications during and after surgery, characterised by persistent oozing and haemorrhage. Ehrlichiosis causes mild to moderate coagulopathy through a range of mechanisms, and this is compounded by coinfection with other tick-borne diseases such as babesiosis and A. platys co-infections.

In veterinary science we refer to some diseases as ‘great pretenders’, canine hypoadrenocorticism for example, since their clinical diversity may challenge our diagnostic reasoning. Ehrlichiosis is another example—mimicking (and causing) a wide range of inflammatory and noninflammatory syndromes. CME is associated with much immune dysregulation in its own right, and can present with pyrexia of unknown origin, or signs consistent with IMPA, IMHA, ITP, and meningitis. Such presentations may not bring CME to mind immediately, especially if you work in areas outside the brown dog tick range, but the suspicion for ehrlichiosis should be increased in a patient with any of the following history:

If your practice is located within the enzootic range of the brown dog tick,

If ticks have been seen on the dog, especially in recent weeks or months. The culprit is the brown dog tick, not paralysis ticks, so further questioning and local knowledge is important here, If there is any question about the owner’s compliance with regard to tick prophylaxis, If the dog receives solely an isoxazoline product such as Nexgard, Credelio, Simparica or Bravecto. Whilst these drugs provide excellent protection against ticks generally, their mode of action is systemic. The tick needs to feed for a while in order to ingest sufficient active agent to be killed. This is too slow to protect against transmission of E. canis, which can occur in less than 3 hours (see later),

If the dog has travel history from central or northern Australia,

If the dog has been newly acquired and travel history is unknown. This is especially true for pups and dogs that have been rehomed. There are cases of CME reported in southern Australia in just this situation after it was discovered that the dogs had come from up north.

Diagnosis of CME is predicated on all-important clinical suspicion, so it’s the signs and history that should first alert the clinician. Most dogs will have one or more of these clinical signs:

Pyrexia (often >40°C in acute stage)

Lethargy and malaise

Hypo-or anorexia

Unexplained weight loss to cachexia

Ocular signs (corneal oedema, conjunctivitis)

Dry eye

Blindness

Lymph node enlargement

Petechiae

Epistaxis

Dyspnoea and coughing

Neurological signs

Diarrhoea

Persistent infections (and sepsis)

Oedema (limb, generalised or scrotal)

Abdominal distension (ascites)

Hepatosplenomegaly

Full bloodwork, including C-reactive protein (CRP), and urinalysis should be performed as screening tests. One or more abnormalities usually exist in CME, but confirmation of the diagnosis requires PCR and/or serology. The disease is notifiable (this might change) so local veterinary authorities should be advised and testing is performed in state and territory laboratories. Check their website for instructions on sample submission.

There is a pressing need for a reliable in-clinic test for ehrlichiosis in Australia. The notifiable status of CME currently mandates formal testing at regional government labs; however, we need rapid, point-of-care test(s) for suspected cases and prior to surgery in endemic areas, for example. Vets have been using a number of commercially available kits, with variable results, but none has yet been tested rigorously against a gold standard (e.g. IFAT) for the Australian strain of E. canis (see later).

A wide range of laboratory abnormalities have been reported including:

Haematology

May be normal

Thrombocytopenia

Anaemia – regenerative or non-regenerative

Inflammatory leucogram

Monocytosis

Or bi- or pancytopenia

Biochemistry

May be normal

Increased globulins (polyclonal, rarely a ‘monoclonal spike’)

Albumin normal or decreased

CRP elevation (often very high)

Liver enzyme activities increased

Pre-renal azotaemia

SDMA elevation

In addition, case reports and case series overseas associate CME with various organ pathologies and clinical syndromes, including interstitial pneumonia and pulmonary hypertension,10 hepatitis,11 meningomyelitis,12 and increased risk of developing chronic kidney disease.13

Doxycycline is the antimicrobial of choice for CME at a dose rate of 10mg/kg/day for 28 days (this can be given divided or as a single dose). There are at least 11 studies behind this ACVIM Consensus Statement recommendation from over 20 years ago.14 Evidence for its efficacy comes from in vitro studies that indicate E. canis is highly susceptible to doxycycline, requiring a low minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) (0.03µg/mL).15

There is usually a good clinical response to doxycycline in the acute phase; however, some dogs remain bacteraemic (infectious to ticks) for unpredictably variable periods of time during the course of antimicrobial drug treatment, and some after cessation of doxycycline.16,17 Unfortunately, therefore, clinical resolution does not always equate to ‘cure’, i.e. bacterial sterilisation, and this should be remembered if dogs later develop clinical illness that could be attributable to recrudescence of ehrlichiosis.

Unfortunately not many. Different tetracycline formulations should be effective (including minocycline, oxytet) but there is less consensus about dose frequency and duration.18 Rifampicin, an ansamycin antibiotic that is used to treat mycobacterial diseases in humans, is also efficacious against E. canis in vitro, but should not be considered first line due to our responsibilities with respect to antimicrobial stewardship and because of the need to monitor liver enzyme activity during therapy. Imidocarb dipropionate (a treatment for babesiosis) was originally used to treat CME; however, recent studies have indicated this drug is not efficacious for CME.18

In practical terms there is little we can do as vets to determine the success, or otherwise, of antibiotic treatment. The sensitivity of PCR detection is low in the subclinical phase and whilst monitoring of serial antibody titres would help, there are currently no labs in Australia that provide end-point titre measurements. Furthermore, antibody levels for E. canis remain elevated for protracted periods after infection, so gaining the owners cooperation for repeated testing would most likely be challenging!

Other treatments involve managing complications and other pathological effects of E. canis infections, especially in the ‘chronic’ phase. The main considerations are:

Blood loss anaemia requiring blood transfusion(s), Sepsis as a component of bone marrow failure requiring parenteral antibiotics based on blood culture and antimicrobial sensitivity testing, Pancytopenia due to aplastic anaemia/bone marrow aplasia requiring blood transfusion(s).

Severe epistaxis, in particular, can be challenging to manage. While most cases will cease spontaneously, eventually, treatments that have been suggested including sedation, physical packing the external nares with absorbent material, whole blood transfusions (or platelet transfusions, if available), tranexamic acid, and

DDAVP, which enhances platelet function by increasing serum levels of von Willebrand factor.18

Until the arrival of CME, the most serious tick-associated disorder afflicting dogs in Australia was tick paralysis, yet in comparison with the rapid transmission of E. canis from brown dog ticks described above,⁶ the neurotoxins injected by I. holocyclus do not take effect until 3-4 days after tick attachment. Understanding this difference in timing is crucial with respect to the use of acaricides to protect against CME.

Topically-acting synthetic pyrethroids (e.g. flumethrin) are a class of acaricides that exert their protective effect through repellency (and kill), preventing tick attachment, and have been shown to protect dogs against transmission of E. canis. 19 Seresto® collars contain flumethrin in addition to imidacloprid and are now have a registration claim in Australia to reduce the risk of transmission of E. canis infection.

The other major class of acaricides currently in use in companion animal practice, the isoxazolines, act systemically, requiring ticks to feed in order to work. This prevents tick paralysis but does not protect dogs from acquiring CME,20 although isoxazoline products stop onward transmission of E. canis from an infected dog, and have proven a valuable adjunctive treatment to reduce tick burdens where dogs are housed.

Ehrlichia canis is related to several members of the Anaplasmataceae that are recognised to be zoonotic, including E. chaffeensis, E. ewingii and E. muris eauclairensis, and there is evidence for the zoonotic potential of E. canis from molecular and serological testing in Central and South America.21 However, there are no reports of infection in humans that implicate the Asian/Taiwan genogroup of E. canis that has been detected in Australia.22 It therefore seems unlikely that E. canis will be of public health concern in Australia.

It is fortunate and, indeed, somewhat surprising, that Australia remained free of CME for so long, considering the abundant population of brown dog ticks across the north. Mandatory pre-import screening (comprising IFAT) was established in September 1995, and dogs testing positive were prohibited entry into the country.

Regardless, current surveillance data indicate that infected dogs (or ticks) have been detected in most states and territories, and the disease is now (2023) regarded as endemic. There is no hope of eradication,

so veterinarians must add CME to differential diagnosis of canine illnesses in northern Australia and in travelled dogs, and start prompt treatment when cases are diagnosed. Canine ehrlichiosis is, unfortunately, here to stay.

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

This research did not receive any specific funding.

1. Rar V and Golovljova I (2011) Anaplasma, Ehrlichia , and ‘‘ Candidatus neoehrlichia ’’ bacteria: Pathogenicity, biodiversity, and molecular genetic characteristics, a review. Infect. Genet. Evol. 11: 1842–1861. https://doi:10.1016/j.meegid.2011.09.019

2. Donatien, A., Lestoguard, F. (1935) Existence en Algerie d’une Rickettsia du chien. Bull. Soc. Pathol. Exot. 28: 418–419.

3. Nims, R.M., Ferguson, J.A., Walker, J.L. et al. (1971) Epizootiology of tropical canine pancytopenia in Southeast Asia. J. Am. Vet. Med. Assoc. 158: 53-63.

4. Slapeta, J., Chandra, S. and Halliday, B. (2021) The ‘‘tropical lineage” of the brown dog tick Rhipicephalus sanguineus sensu lato identified as Rhipicephalus linnaei (Audouin, 1826). Int. J. Parasitol 51: 431-436. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijpara.2021.02.001

5. Dantas-Torres, F. (2010) Biology and ecology of the brown dog tick, Rhipicephalus sanguineus. Parasit. Vect. 3: 26.

6. Fourie JJ, Stanneck D, Luus HG, et al. (2013) Transmission of Ehrlichia canis by Rhipicephalus sanguineus ticks feeding on dogs and on artificial membranes. Veterinary Parasitology 197: 595-603. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.vetpar.2013.07.026

7. Bremer WG, Schaefer JJ, Wagner ER, et al. (2005) Transstadial and intrastadial experimental transmission of Ehrlichia canis by male Rhipicephalus sanguineus Veterinary Parasitology 131: 95-105. doi:10.1016/j.vetpar.2005.04.030.

8. Harrus, S. (2015) Perspectives on the pathogenesis and treatment of canine monocytic ehrlichiosis (Ehrlichia canis). Vet. J. 204: 239-240.

9. Harrus S, Kass PH, Klement E, et al. (1997) Canine monocytic ehrlichiosis: a retrospective study of 100 cases, and an epidemiological investigation f prognostic indicators for the disease. The Veterinary Record 141: 360-363.

10. Toom ML, Dobak TP, Broens EM et al. (2016) Interstitial pneumonia and pulmonary hypertension associated with suspected ehrlichiosis in a dog. Acta Vet Scandinavia 58:46

11. Mylonakis ME, Kritsepi-Konstantinou M, Dumler JS et al. (2010) Severe

hepatitis associated with acute Ehrlichia canis infection in a dog. J. Vet. Int. Med. 24: 633-638.

12. Frankar H, Le Boedec K, Beurlet S et al. (2023) Suppurative spinal meningomyelitis in a dog with intra-neutrophilic cerebrospinal fluid cells Ehrlichia canis morulae. Vet. Clin. Path. 52: 119-122.

13. Burton W, Drake C, Ogeer J et al. (2020) Association between exposure to Ehrlichia spp. and risk of developing chronic kidney disease in dogs. J Am Anim Hosp Assoc 56: 159-164.

14. Neer TM, Breitschwerdt EB, Greene RT, et al. (2002) Consensus statement on ehrlichial disease of small animals from the infectious disease study group of the ACVIM: American College of Veterinary Internal Medicine. Journal of Veterinary Internal Medicine 16: 309–315.

15. Branger S, Rolain JM and Raoult D (2004) Evaluation of Antibiotic Susceptibilities of Ehrlichia canis, Ehrlichia chaffeensis , and A naplasma phagocytophilum by Real-Time PCR. Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy 48: 4822-4828.

https://doi.org/10.1128/AAC.48.12.4822-4828.2004

16. Harrus S, Waner T, Aizenberg I, et al. (1998) Therapeutic effect of doxycycline in experimental subclinical canine monocytic ehrlichiosis: Evaluation of a 6-week course. Journal of Clinical Microbiology 36: 2140-2142.

17. Schaefer JJ, Needham GR, Bremer WG, et al. (2007) Tick Acquisition of Ehrlichia canis from Dogs Treated with Doxycycline Hyclate. Antimicrobial agents and Chemotherapy 51: 3394-3396.

18. Mylonakis ME, Harrus S and Breitschwerdt EB (2019) An update on the treatment of canine monocytic ehrlichiosis (Ehrlichia canis) The Veterinary Journal 246: 45-53.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tvjl.2019.01.015

19. Stanneck D, Fourie JF (2013) Imidacloprid 10 % / Flumethrin 4.5 % Collars(Seresto®, Bayer) Successfully Prevent Long-Term Transmission of Ehrlichia canis by Infected Rhipicephalus sanguineus Ticks to Dogs. Parasitology Research 112: S21-S31. DOI 10.1007/s00436-013-3278-6.

20. Burgio F, Meyer L and Armstrong R (2016) A comparative laboratory trial evaluating the immediate efficacy of fluralaner, afoxolaner, sarolaner and imidacloprid + permethrin against adult Rhipicephalus sanguineus (sensu lato) ticks attached to dogs. Parasites & Vectors 9: 626. https://DOI 10.1186/s13071-016-1900-z

21. Unver A, Perez M, Orellana N, et al. (2001) Molecular and Antigenic Comparison of Ehrlichia canis Isolates from Dogs, Ticks, and a Human in Venezuela. Journal of Clinical Microbiology 38: 2788–2793.

22. Neave MJ, Mileto P, Joseph A, et al. (2022) Comparative genomic analysis of the first Ehrlichia canis detections in Australia. Ticks and Tick-borne Diseases 13: 101900. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ttbdis.2022.101909

Team Leader

Elizabeth Macarthur Agricultural Institute

Team Leader

Elizabeth Macarthur Agricultural Institute

Menangle NSW

e. mark.westman@dpi.nsw.gov.au

We have had 3 E. canis PCR-positive samples since the 2020 case we wrote up in the C&T—Billy Leso (so 4 dogs in total). Billy had recently been adopted by new owners on the South Coast after spending a few weeks with a foster carer in Sydney following relocation from the Northern Territory (NT). All 4 dogs had recently been rehomed to NSW from the NT.

Note that I am NOT including E. canis antibody-positive results here as I would not rely on solely serology for diagnosis.

If possible, ticks should also be collected from the affected dog, placed in a small container (e.g. a urine specimen jar or a plain tube) with 2 mL of 70% ethanol and submitted to the state veterinary laboratory with the collected blood samples (≥ 1 mL serum and ≥ 2 mL EDTA blood) for tick identification and E. canis testing (serology and PCR testing). If ethanol is not available, submitting ticks dry will also suffice.

Interestingly, we have had 5 A. platys positive samples since 2020! All dogs were recently rehomed from the far north QLD or SA.

C&T Download Mark Westman's article

‘Billy’ – The First Case of Ehrlichia canis Diagnosed In New South Wales, C&T No. 5897, Issue 304 Sept 2021.

We often get asked what is the real distribution of the brown dog tick in Australia?

In Australia, only the tropical species of brown dog tick, Rhipicephalus linnaei, is found. The temperate species, Rhipicaphalus sanguineus, is not present in the country. Our current best estimate of the distribution of brown dog ticks in Australia can be seen in the figure provided (Chandra et al. 2020, 2021; Šlapeta et al. 2021). While we have observed brown dog ticks in places like Sydney, they have only been found on dogs that have been relocated from areas above the line on the figure. We have yet to confirm the sustained breeding of brown dog ticks yearround in the cooler southern regions of Australia.

The reason for the name change is that it has been discussed for over a decade, and there was a consensus that a split was necessary. This is because the tropical and temperate lineages behave differently and appear to have different tendencies for transmitting diseases. As a result, instead of using informal names, we now have two formal scientific names.

In Australia, the common name for the brown dog tick can still be used, but there is another commonly used name—the kennel tick. This name is actually very convenient because it indicates the tick’s life history. It informs us about the association of the tick with dog dwellings, such as kennels. These ticks love to breed in kennels, where they can establish their population, often in the hundreds or thousands.

References

S Chandra, GC Ma, A Burleigh, G Brown, JM Norris, MP Ward, D Emery, J Šlapeta (2020). The brown dog tick Rhipicephalus sanguineus sensu Roberts, 1965 across Australia: Morphological and molecular identification of R. sanguineus sl tropical lineage. Ticks and tick-borne diseases 11 (1), 101305

S Chandra, B Halliday, J Šlapeta (2021) Museum material of Rhipicephalus sanguineus sensu Roberts (1965) collected in 1902–1964 from Australia is identical to R. sanguineus sensu lato tropical lineage at the mitochondrial DNA 12S rRNA level. Medical and Veterinary Entomology 35 (3), 315-323

J Šlapeta, S Chandra, B Halliday (2021) The “tropical lineage” of the brown dog tick Rhipicephalus sanguineus sensu lato identified as Rhipicephalus linnaei (Audouin, 1826). I nternational Journal for Parasitology 51 (6), 431-436

If you’re reading the Control & Therapy Series for the first time, welcome. The C&T Series was established in April 1969 as a veterinary forum by the CVE’s first Director, the legendary Dr Tom Hungerford OBE BVSc FACVSc HAD. Tom wanted to get the clinicians writing.

…not the academic correctitudes, not the theoretical niceties, not the super correct platitudes that have passed the panel of review… not what he/she should have done, BUT WHAT HE/SHE DID, right or wrong, the full detail, revealing the actual “blood and dung and guts” of real practice as it happened, when tired, at night, in the rain in the paddock, poor lighting, no other vet to help

To date, 5,980 and 158 practical and relevant C&T and Perspective articles have been published in this unique forum. Authors receive no financial recompense; rather, they contribute articles to share their experiences with their peers, add to practical veterinary knowledge and improve animal welfare everywhere. (And get to enjoy reading their article in print!)

Now every one of you who has done anything practical that’s not easily obtainable in all the common textbooks, write it up.

– Tom HungerfordIt doesn’t have to be long – some of the best articles have been a mere paragraph or two. Please include figures, tables, high resolution images for print and videos for the eBook version if you have them and send to: cve.marketing@sydney.edu.au. Our veterinary editors review all submissions. Rest assured, if they have any questions or concerns, you will be contacted before publication. Join us!

…it's still the best publication by far for the practical vet out there… Every article is worth a read.

– Pete Coleshaw, Veterinarian, UKThe digital Control & Therapy (C&T ) Series is now OPEN ACCESS to the Veterinary Profession Worldwide from September 2023

North

Nowra Veterinary Hospitale. sammysingo@gmail.com

C&T No. 5982

Opal has diffuse idiopathic skeletal hyperostosis (DISH). This can cause limited spinal range of motion, nerve impingement leading to spinal pain and pain on the legs. The nerve impingement can also cause muscle weakness, paresis, and changes in spinal reflexes.

If there is lack of movement there may be muscle atrophy (plus possibly some neurogenic atrophy), plus chronic pain may lead to Opal looking and acting older than 7-years-old.

Moira van Dorsselaer BVSc

The Cat Clinic Hobart, New Town TAS

e. moira@catvethobart.com.au

t. +613 6227 8000

Opal was diagnosed with diffuse idiopathic skeletal hyperostosis (DISH) after discussion with Dr Richard Malik, as I had never actually seen a case like this before.

DISH is a systemic non-inflammatory disorder of the axial and peripheral skeleton that has also been described in humans and dogs.

DISH results in the ossification of soft tissues including spinal ventral longitudinal ligaments and sites of attachment of tendons and capsules to bone. In dogs and humans the prevalence increases with age.

In the Veterinary Quarterly 33:1, 30-42 (2013) ‘Spinal hyperostosis in humans and companion animals’ stated no studies describing DISH in cats have been published.

The Journal of Small Animal Practice (2016) 57 3335 published the article ‘Diffuse idiopathic skeletal hyperostosis of the spine in a nine-year-old cat’ which described a case of DISH in a nine-year-old intact female domestic shorthair cat and to the authors’ knowledge was the first published report of feline diffuse idiopathic skeletal hyperostosis.

Vet Record Case Reports (07 June 2021) published the article ‘Radiographic and MRI characteristics of diffuse idiopathic skeletal hyperostosis in a cat presented with a painful chronic ambulatory paraparesis’ which described a case of DISH in a nine-year-old male neutered Maine Coon and to the authors’ knowledge, this is the first case report describing the radiographic and MRI characteristics of DISH in a feline patient.

Clearly—the skeletal changes in this cat ARE SEVERE. There is every possibility that there is intervertebral disc protrusion adding to the cat’s disability by compressing the spinal cord or nerve roots exiting intervertebral foramina. The only way to determine this is by advanced imaging, CT, a CT myelogram, or an MRI scan (ideally all three!). The problem of course is we do not know what causes DISH in cats or dogs, and we cannot treat the underlying problem, so even if there is a discrete surgical lesion—can we be sure fixing it will help the cat? And the imaging would likely cost $5,000 and surgery might cost another 5-10 thousand dollars. A lot of money to pay with an uncertain prognosis.

Due to finances CT scan was not an option for Opal’s owners and we treated Opal with a single dose of Solenisa™ via subcutaneous injection to which she responded well initially. Her owners also continued with oral meloxicam daily. Sadly Opal was recently euthanised due to progressive worsening of her clinical signs, poor response to ongoing treatment and her owners not being able to cope with knowing that Opal might be suffering and in pain.

Thanks to all our readers who answered the ‘What’s Your Diagnosis?’ question in the last issue. Congratulations to Samantha who won the $100 CVE credit for the best answer!

Read

Authors’ views are not necessarily those of the CVE

Figure 2. Dorsoventral forelimb and cervical spine

Figure 3. Lateral thoracic spine

Figure 4. Ventrodorsal hips

Figure 2. Dorsoventral forelimb and cervical spine

Figure 3. Lateral thoracic spine

Figure 4. Ventrodorsal hips

The prize is a CVE$400 voucher

Samantha Coomes BVSc

Marina Worden BVSc

4 Paws Veterinarians, Townsville

t. (07) 4723 1988 | e. charlesstreetvet@hotmail.com

C&T No. 5983

James Cook University, Townsville

Veterinary Pathology Resident

Bullet is a 7-year-old male Bull Arab x Border collie crossbreed. He was adopted by our client (who is one of our nurses) at 10-months-old. Castration was performed at 10-months-of-age through the rescue organisation, prior to the client adopting Bullet. Therefore, we are unsure if it was routine or cryptorchid castration. Bullet has previously been treated for heartworm infection but is currently up to date with all preventative care.

Bullet developed a mass where his scrotum would be if he were an entire male dog. The lump was noted during a bath, and was absent at vaccination two months prior. The lump remained stable for the two weeks between noticing the lump and removal. There were no other abnormalities noted at home or during physical examination.

An FNA of the lump was performed during consult. After consulting with Alinta, it was determined the FNA contained germinal epithelial cells. I could be forgiven for thinking the cells were possibly spindle cells, due to the morphology of a few singular cells, or agranular round cells. Germinal epithelial cells behave like epithelial cells forming cohesive clusters of cells, whereas spindle cells routinely do not. The granular cytoplasm of germinal epithelial cells could also be mistaken for mast cells.

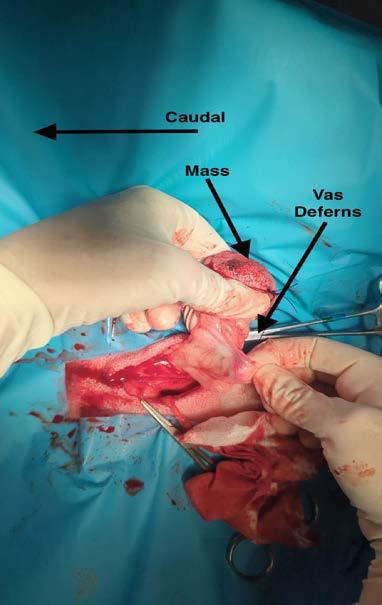

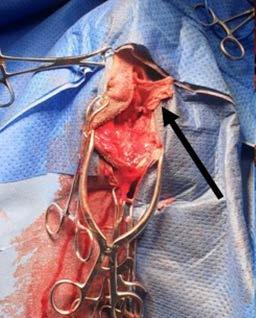

A lumpectomy was performed the following week. The lumpectomy was essentially a scrotal ablation, with removal of the lump through the scrotal ablation site. Care was taken not to separate the lump from the surrounding tissue. The vas deferens was located, attached to the distal edge of the lump. The vas deferens and tunica were ligated as deep as possible. The lump was submitted for histopathology.

Quoted directly from the report provided by Drs Alinta Kalns and Linda Hayes:

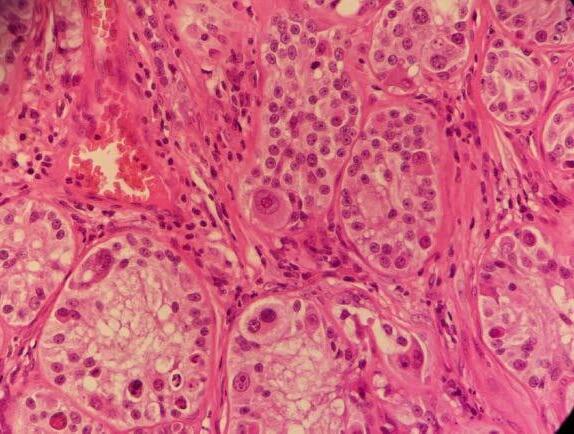

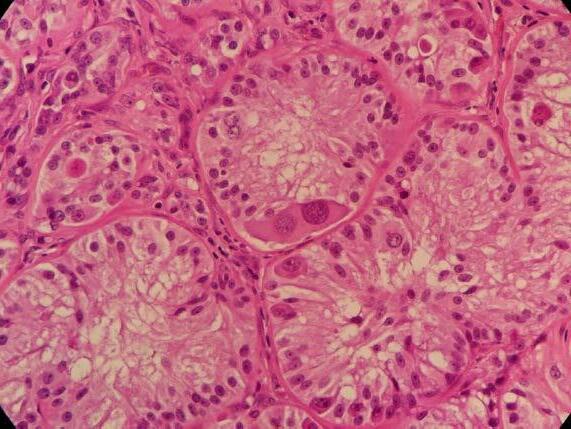

‘Scrotum: Expanding the subcutis of the scrotum, adjacent to a large vascular plexus, is an encapsulated, well demarcated, densely cellular neoplasm composed of lobules and tubules of polygonal to columnar cells arranged perpendicularly to the basement membrane and supported by a delicate to moderate fibrous

stroma. These cells exhibit moderate anisocytosis and anisokaryosis, have indistinct cell borders, and low to ample amounts of eosinophilic, granular cytoplasm that is frequently vacuolated. Nuclei are oval to round with finely stippled to vesicular chromatin and one or more prominent, eosinophilic nucleoli. Infrequent karyomegaly and binucleate cells as well as rare multinucleated cells are observed. Mitoses range from zero to two per HPF, averaging 0.7 per HPF. Frequently, cells exhibit hypereosinophilia and pyknosis.

Within one section, three separate islands of neoplastic cells expand the stroma away from the main neoplasm. Multifocally scattered throughout the neoplasm are mild to moderate perivascular infiltrates of lymphocytes and plasma cells.

In one section, the stroma between the mass and the overlying dermis, contains a poorly defined area of tortuous, variably sized clear spaces lined by flattened to mildly plump, simple squamous epithelial cells (endothelium). No mitotic figures are observed in examination of ten HPFs’.

Sertoli Cell Tumour

Secondary mass within the wall of scrotum—suspected to be an area of lymphangiomatosis.

Comments

With an absence of identifiable normal testicular tissue, the Sertoli cell tumour is likely to have arisen from a congenital or traumatic remnant of testicular tissue within the spermatic cord or scrotum. Thus, this case represents one of the rare circumstances in which this can occur and the challenges of diagnosing it as a primary clinician using in-house diagnostic techniques.

A case report of 17 castrated animals with sertoli cell tumours (Doxsee, A., Yager, J., Best, S., & Foster, R. (2006, August)) suggests ectopic testicular tissue, polyorchidism and transplantation of testicular tissue during castration as aetiologies. The median time to development of a Sertoli cell tumour was 8 years.

The second lesion, lymphangiomatosis, is a rare, benign, circulatory disturbance and/or developmental anomaly of lymphatic vessels. These are poorly circumscribed masses that can recur due to their irregular infiltrative nature. Differentials include a bloodless haemangioma or well-differentiated lymphosarcoma (however no mitotic figures were observed in ten HPFs).

Darby W. Walmsley BVSc MANZCVS (SAS) AFHEA Fcert (E&CC)

Animal Welfare League Brisbane, Queensland e. darby.walmsley@gmail.com

Adrian Wallace BVSc (Hons) MANZCVS DipECVS

Geelong Animal Referral Services, Newton Victoria e. hospital@garsvets.com.au

C&T No. 5984

An 8-year-old, entire male Jack Russell Terrier (9 kg) was referred for evaluation of a right-sided perineal swelling that had been present for approximately 3-months. The patient developed acute lethargy, pain, stranguria and tenesmus 3-days prior to presentation. Physical examination identified an extensive, right-sided perineal hernia (PH).

Digital rectal examination confirmed right-sided rectal sacculation with accumulation of faeces. Subjectively, the left pelvic diaphragm was intact. The remainder of the physical examination and blood testing was unremarkable.

Ultrasonography of the right perineal swelling revealed a fluid-filled object, suspected to be the urinary bladder, herniated through the pelvic diaphragm. Faecal matter was also apparent on ultrasound. Orthogonal survey abdominal radiography was performed. A urethral catheter was placed, and positive contrast cystography performed by instilling 5mL of contrast media (Urografin®; Bayer Australia Ltd, Pymble NSW, 2073, Australia) into the urinary catheter. Repeat orthogonal radiography confirmed urinary bladder retroflexion (Figure 1a). The bladder was then manually reduced into an appropriate anatomical position (Figure 1b). Due to the severity of the deficit, the bladder was unable to remain

in this position and returned into a retroflexed position despite multiple attempts at reduction.

The patient was pre-medicated with methadone (0.2 mg/ kg IV). Anaesthesia was induced with propofol (4 mg/kg IV; Lipuro 1%, Braun Australia Pty Ltd, Bella Vista NSW, Australia) and maintained with isoflurane (Isoflo®, Zoetis Australia Pty Ltd, Rhodes NSW, Australia) in oxygen. The abdomen and perineal regions were clipped and prepared with chlorhexidine and an alcohol solution, and the patient initially positioned in dorsal recumbency.

A fentanyl constant rate infusion (10 µg/kg/hr IV; Sublimaze®, Janssen-Cilag Pty Ltd, Macquarie Park NSW, 2113, Australia) was administered intra-operatively.

A midline coeliotomy with parapreputial extension was performed. The bladder was manually reduced into the

abdomen. A cystopexy was performed via seromuscular incision in the bladder apex, apposed to an incision in right body wall with 2 simple continuous suture lines (3/0 Polydioxanone). A colopexy was also performed by seromuscular incision in the colon apposed to an incision in the left body wall with 2 simple continuous suture lines. Omentum was then wrapped around the colopexy site and secured with a cruciate suture.

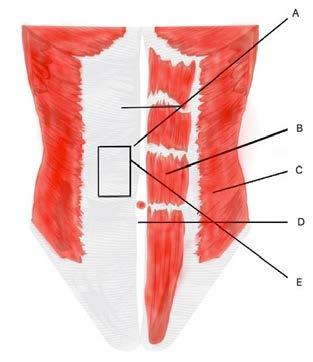

A 5 cm x 5 cm section of rectus abdominis aponeurosis was harvested from the right side of the abdomen (Figure 2) and placed within a moistened swab. The donor site was chosen to leave healthy rectus sheath immediately adjacent to midline to facilitate midline closure. No attempt was made to close the donor site.

At time of abdominal exploration, the prostate appeared enlarged, irregular, and cystic. A prostatic biopsy was taken from the left side of prostate (with histopathology later returning as benign prostatic hyperplasia). The abdomen was then copiously lavaged with sterile saline and routine midline closure was performed with 2/0 Polydioxanone in a simple continuous pattern engaging the external leaf of the rectus sheath. The subcutaneous tissue was closed with 4/0 Poliglecaprone 25 in a simple continuous suture pattern. The skin was closed with staples. Open castration was performed via a pre-scrotal incision. Vas deferens and vascular pedicle were ligated (simple ligatures) separately with 3/0 Polydioxanone and subsequently transected. The subcutaneous tissue was closed with 4/0 Poliglecaprone 25 in a simple continuous suture pattern. The skin was closed with staples.

The patient was then repositioned in sternal recumbency in a perineal stand. A paramedian approach to the right ischiorectal fossa was performed. Omental fat was immediately apparent and was bunch ligated with 3/0 Polydioxanone, and subsequently resected. Significant atrophy of both the levator ani and coccygeus muscles was apparent. Chronic bladder herniation had resulted in a large deficit between the external anal sphincter, coccygeus and levator ani muscles. An internal obturator transposition was performed with transection of the tendon of the internal obturator to facilitate increased transposition distance. The internal obturator was apposed to the external anal sphincter, coccygeus and levator ani muscles with 2/0 Polypropylene in a simple interrupted pattern (preplaced). However, a significant deficit remained dorsally following internal obturator transposition. The rectus sheath graft was apposed to the sacrotuberous ligament, the internal obturator, external anal sphincter and subcutaneous tissue dorsally with 2/0 Polypropylene in a simple interrupted pattern (Figure 3) ensuring appropriate longitudinal placement of the graft in the region of maximal tension. The subcutaneous tissue was closed with 4/0 Poliglecaprone 25 in a simple continuous pattern. The skin was closed with 4/0 Poliglecaprone 25 in an intradermal pattern.

The patient received intra-and post-operative cefazolin (22 mg/kg IV; Cefazolin-AFT, AFT Pharmaceuticals, North Ryde, NSW, Australia) and fentanyl CRI (10 µg/kg/hr IV), post-operative meloxicam (0.1 mg/kg subcutaneously; Meloxicam, Ilium, Troy Laboratories Australia Pty Ltd, Australia) and a transdermal fentanyl patch (50 µq/h; Durogesic® 50, Janssen-Cilag Pty Ltd, Macquarie Park NSW, Australia).

The patient presented at both 2- and 12- weeks postoperatively for re-evaluation. Physical examination at 2-weeks revealed some mild post-operative swelling around the right perineal region, which was no longer apparent at 12-weeks post-operatively. The remainder of the physical examination at both time points were unremarkable. Rectal examination at both time points was unremarkable. A telephone update was provided at 6 and 12 months postoperatively by the client. According to the client, the patient was clinically healthy, and displayed no signs of hernia recurrence or associated clinical signs, including tenesmus, dysuria, or perineal swelling.

PH is a common surgical condition of intact males and is likely the result of multifactorial influences.1 The proposed causes of PH include muscular atrophy,1-3 hormonal imbalances and gender variances,4 and prostatic disease.5-7 Although the understanding of the

aetiology is incomplete and ongoing, the disease process is characterised by weakening and atrophy of muscles of the pelvic diaphragm, including the levator ani and/or coccygeus muscles, resulting in the herniation of intrapelvic and/or intra-abdominal structures.1-3 The most common clinical signs ascribed to perineal herniation may include a non-painful swelling lateral to the anus, constipation, obstipation, dyschezia, tenesmus, rectal prolapse, stranguria, anuria, vomiting, and/or faecal incontinence.¹

Internal obturator muscle transposition is now considered the gold standard technique for treatment of dogs with PH.1,8 However, some surgeons advocate the use of adjunctive techniques for reinforcement of the repair if there are concerns about the severity, size, and chronicity of the hernia. A major advantage of the use of rectus abdominis aponeurosis is the low donor and recipient-site morbidity comparatively to previously described techniques when adjuvant reinforcement is required, as well as being biomechanically sound with resistance to significant tensile forces. It is in the authors’ recommendation, however, that fascia implantation should be complemented with internal obturator muscle transposition to decrease graft strain and may improve survivability. Although graft rejection was not observed clinically in the post-operative period, without further advanced imaging, the authors are unable to comment on graft survival long-term.

The use of synthetic substances, such as polypropylene mesh, has the inherent risk of suture sinuses/infection and other mechanism of failure, which require implant removal. Some surgeons therefore advocate the use of autogenous material where possible, with synthetic material reserved for salvage procedures. We were able to hypothesise that the use of an autogenous graft would likely reduce the risk of implant related complications, including infection.

1. Gill SS, Barstad RD. A Review of the Surgical Management of Perineal Hernias in Dogs. J Am Anim Hosp Assoc 2018; 54:179–187. DOI 10.5326/JAAHA-MS-6490

2. Desai R. An anatomic study of the canine male and female pelvic diaphragm and the effect of testosterone on the status of levator ani of male dogs. J Am Anim Hosp Assoc 1982;18:195–202.

3. Seim HB. Surgical management of perineal hernia. Proc North Am Vet Conference 2009;1571–3.

4. Hayes HM, Wilson GP. Hormone-dependent neoplasms of the canine perianal gland. Cancer Res 1977;37(7 Pt 1):2068–71.

5. Krahwinkel DJ. Rectal diseases and their role in perineal hernia. Vet Surg 1983;12:160–5.

6. Hosgood G, Hedlund CS, Pechman RD, et al. Perineal herniorrhaphy: per- ioperative data from 100 dogs. J Am Anim Hosp Assoc 1995;31(4):331–42.

7. Head LL, Francis DA. Mineralized paraprostatic cyst as a potential contributing factor in the development of perineal hernias in a dog. J Am Vet Med Assoc 2002;221:533–5.

8. Hardie EM, Kolota RJ, Earley TD, et al . Evaluation of internal obturator muscle transposition in treatment of perineal hernia in dogs. Vet Surg 1983;12(2):69–72.

Authors’ views are not necessarily those of the CVE

Gordon Veterinary Hospital, Pymble, NSW 2073

t. 02 9498 3000

e. info@gordonvet.com.au

C&T No. 5985

Dusty is an 11-year-old male neutered Domestic Long Hair cat (5.9 kg), who was acquired as a kitten. He is an indoor cat and is the only cat in the household. Routine F3 vaccinations and monthly parasite prophylaxis are up to date, and he is fed Hills i/d wet and dry formulations after being diagnosed with IBD in 2021. Dusty had also been diagnosed with diabetes mellitus in 2022 and has been managed with glargine insulin.

Dusty’s previous veterinarian first detected a grade III/IV systolic heart murmur and tachycardia on routine physical exam in 2013, when Dusty was 1-yearold. Subsequently, an in-house echocardiogram was performed in 2014 and he was diagnosed with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. At this time, the left atrium (LA) and Left atrial to aortic ratio (LA:Ao) were 1.35 cm and 1.4, respectively. Systolic anterior motion of the mitral valve was observed and Dusty was started on atenolol (5mg transdermal q 12h). Annual in-house echocardiograms were recommended to monitor for disease progression.

Dusty first presented to our clinic in 2017 (now aged 6-years-old). He had a grade III/VI parasternal systolic murmur, regular heart rate, and no dyspnoea. His resting respiratory rates at home were consistently less than 30 breaths per minute. We continued to see Dusty in for annual in-house echocardiograms. Between 2019 and 2020, Dusty’s owner reported three syncopal-like episodes that appeared to be triggered by overexertion.

In 2021, during his annual health examination, an

arrhythmia was first detected (irregularly irregular). His heart murmur intensity was unchanged and he had remained well in himself at home as reported by the owner. His echocardiogram showed that the LA and LA:Ao ratio had mildly increased to 1.5 cm and 1.7, respectively. We started him on clopidogrel 75mg (1/4 tablet Plavix PO q24h), alongside the transdermal atenolol, however, Dusty would not tolerate daily tableting at this time, so was changed to Astrix Aspirin 100mg (5 granules given in food twice weekly).

In 2022, an in-house echocardiogram showed a mass effect within the LA with chamber enlargement. The arrhythmia remained present, and Dusty’s mucous membranes appeared slightly cyanotic. Despite this, Dusty had reportedly remained his normal self at home. We scheduled a referral echocardiogram and electrocardiogram (ECG) with a veterinary cardiologist, Dr Damon Leeder.

The echocardiogram confirmed that Dusty had ventricular hypertrophy with severe left and moderate right atrial enlargement (LA 2.6cm, LA:Ao 2.8) There was no evidence of left ventricular outflow tract obstruction using Doppler. The scan also confirmed the mass effect noted was in fact likely to be a large thrombus, which appeared adherent, within the left auricle/atrium (1.3 x 1.8 cm in size). This was deemed to have arisen secondary to atrial remodeling/stretch, blood flow stasis, and endothelial injury. This thrombus presented a high risk for Dusty developing severe thromboembolism or experiencing sudden cardiac death.

The ECG revealed isorhythmic dissociation although a pathologic AV block was not excluded. The arrhythmia could have been secondary to the sedation (Alfaxan was required for Dusty), however, given it had been audible prior to sedation being administered, it was considered more likely to be arising from his structural heart disease. It was not considered to be of significant hemodynamic importance.

In summary, Dusty was diagnosed with:

1. Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy - severe (stage B2)

2. Left atrial thrombus

3. Isorhythmic dissociation

Due to the presence of a large left atrial thrombus, aggressive antithrombotic therapy was recommended. The aim was to achieve slow dissolution of the thrombus without causing dislodgement or thromboembolism. However, there was a significant risk of thromboembolism with or without therapy and a guarded prognosis was provided to the owner.

After discussion with the owner and further demonstrations regarding how to medicate him

successfully orally, Dusty was re-started on clopidogrel 75mg (1/4 tablet PO q24h). Since this drug is bitter and distasteful to cats and Dusty previously did not tolerate this medication, we advised placing the 1⁄4 tablet in an empty gelatin capsule to facilitate its administration. In addition, rivaroxaban 10mg (1⁄4 tablet PO q24h) was commenced. The aspirin was discontinued and given the possible systolic dysfunction, lack of outflow obstruction, and potential inconsistency of absorption, the transdermal atenolol was also discontinued. No antiarrhythmic therapy was indicated for the ECG changes.

Aside from the thrombus, the severe left atrial enlargement indicated that Dusty was at high risk of developing congestive heart failure in the future. Consequently, the owner was instructed to continue monitoring and recording the sleeping respiratory rate, with normal rates less that 30-35 breaths/min. If the sleeping respiratory rate increased from an established baseline, or consistently exceeded 35 breaths/min, Dusty would need thoracic radiographs/TFAST ultrasound to determine if congestive heart failure had developed.

Dusty was re-evaluated by Damon 6 months later, to recheck the previously diagnosed HCM and left atrial thrombus. The echocardiographic findings were consistent with the previous diagnosis of severe hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. There was persistent markedly severe left and right atrial enlargement (LA 2.6cm, LA:Ao 2.6), and Dusty remained at high risk for CHF. However much to our surprise, following antithrombotic therapy, there was echocardiographic evidence of dissolution of the thrombus. This indicated an excellent response to therapy and the risk of thromboembolism was now much lower.

The previously prescribed antithrombotic therapy (rivaroxaban and clopidogrel) was continued unchanged. No additional cardiac medications were indicated based on this evaluation.

Cats presenting with an atrial thrombus are at high risk of developing feline arterial thromboembolism (ATE). This occurs when the thrombus embolises to a peripheral artery leading to ischemia of the affected vascular bed. Due to the extreme pain of ATE and the widely accepted poor prognosis, owners will often choose euthanasia at diagnosis of an atrial thrombus.

Therapy that includes both clopidogrel and a factor Xa inhibitor, such as rivaroxaban is currently recommended for cats that have either experienced an ATE event or at increased risk of developing ATE.¹ Unfortunately, there is very little research published on the efficacy of dual antithrombotic therapy with clopidogrel and

rivaroxaban in cats and these recommendations are largely based on human literature.² A recent study found that cats treated with clopidogrel and rivaroxaban experienced minimal side effects; had a longer medial survival time and in those cats with intracardiac thrombi, the dual therapy achieved effective thromboprophylaxis.³ Even though this study was retrospective and had a small case population, the results are promising for treatment of cats with HCM and ATE.

This case demonstrates cats diagnosed with large atrial thrombi can be successfully managed with dual antithrombotic therapy and achieve thrombus dissolution. The echocardiographic findings of a large thrombus with existing HCM and diabetes mellitus in a geriatric cat may, in some instances, prompt a discussion around euthanasia. Given Dusty had remained asymptomatic at home and quality of life appeared good, we are grateful his owner decided to treat medically, despite the risks. This case offers hope and justifies attempting dissolution treatment despite a guarded prognosis, so long as the quality of life is otherwise maintained. Dusty continues to have good quality of life and has experienced no adverse effects to the dual antithrombotic treatment with clopidogrel and rivaroxaban. His owner continues to monitor his resting respiratory rate and manage his diabetes mellitus. We plan to review his echocardiogram again in 12 months.

1. Luis Fuentes V, Abbott J, Chetboul V, et al. ACVIM consensus statement guidelines for the classification, diagnosis, and management of cardiomyopathies in cats. J Vet Intern Med 2020; 34: 1062–1077.

2. Yuan J. Efficacy and safety of adding rivaroxaban to the anti-platelet regimen in patients with coronary artery disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. BMC Pharmacol Toxicol 2018; 19:1–9.

3. Lo S, Walker A, Georges C, et al. Dual therapy with clopidogrel and rivaroxaban in cats with thromboembolic disease. J Feline Med Surg 2022; 24(4): 277-283.

C&T No. 5986

Definitive diagnosis of feline infectious peritonitis (FIP) in Australia, requires consistent clinical signs and either: positive FIP immunohistochemistry on biopsies with supportive histopathology, OR positive direct immunofluorescence (DIF), typically performed on effusions. Non-effusive or ‘dry’ FIP cases typically present diagnostic challenges, as clinicians (and owners) are not prepared to put these often-debilitated patients through general anaesthesia and invasive diagnostic procedures.

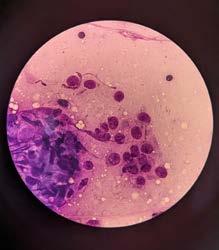

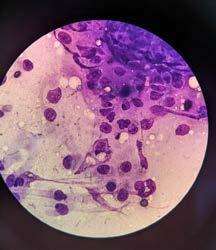

An under-utilised alternative approach is to perform ultrasound guided fine needle aspirates (from lesions) into saline, typically only requiring light sedation. The sensitivity of DIF from aspirates will be lower than that from effusions (i.e., a negative result does not rule out FIP). The sensitivity on effusions is 75%, but on aspirates we estimate it to be more like 40-50%. The specificity, however, remains 100% (i.e., a positive test is definitely FIP).

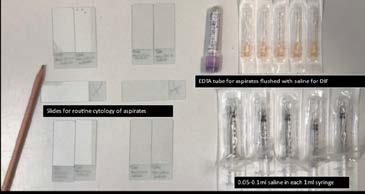

The method we have had the most success with is as follows:

Perform your first couple of aspirates for routine cytology to assess for pyogranulomatous inflammation or other pathological processes. Then have 5-10 x individual 1mL syringes lined up, prefilled with 0.05-0.1mL saline. Have an equal number of needles ready for aspirates. Then have a 2mL EDTA tube (see Figure 1) Do your aspirate (with or without negative pressure), insert the needle into the EDTA vacutainer tube to utilise the negative pressure to suck cells through, then flush 0.05-0.1mL saline through the needle. Finish by drawing back 1mL air to reinstitute some negative pressure into the EDTA tube, ready for the next needle aspirate.

Repeat x 5-10 times.

You need a minimum of 0.5mL for DIF (but no more than 1mL or it will be too dilute).

I place the needle unattached to anything into the EDTA vacutainer first—it’s the tube’s negative

pressure that ‘sucks the cells in’. I find if I attach the saline syringe before the needle is inside the EDTA tube, the first drop of cells starts to push back out the tip of the needle and you ‘lose it’ to the outside of the rubber stopper. You want the aspirate ‘soup’ to be cloudy

You can then submit this for FIP DIF, just as you would do for an effusion. Disregard any comments from the lab technician in relation to the protein analysis, as it obviously won’t be consistent with FIP because it isn’t an effusion.

Veterinary Pathology and Diagnostic Services (VPDS, University of Sydney, B14, NSW, 2004) is the Sydney University laboratory. This is the only lab on the east coast of Australia that offers this test commercially. You can submit directly to them to save the mark-up from external labs, but you need to have an account (which is free) and arrange a courier such as TOLL or TNT (which is not free) yourself for this. Do not use Australia Post, as it will promptly be delivered to the university mail hub and then sit there for up to a week before reaching the Uni laboratory. Alternatively, you can submit via an external laboratory such as ASAP/Vetnostics or IDEXX (the former applies less mark-up).

You can also utilise this technique and submit your aspirate ‘soup’ (or part of it) for FCoV RT-Qpcr; however, you must be aware that false positive can arise, because the PCR cannot distinguish between benign enteric coronavirus (FEC) and fatal FIP. FEC can be found in up to 80% of cats without causing disease or FIP. FEC may drain from the gut in detectable levels to other abdominal sites such as the lymph node or liver and this is how false positive results can arise. IDEXX attempt to classify FIPV Biotypes, please be aware that plenty of cats that are not FIPV biotype positive are positive on definitive tests. So being FCoV positive but biotype negative does not rule out FIP. Essentially, if FCoV RNA is detected from a site unlikely to contain enteric FCoV in a cat with consistent clinical signs, it’s FIP in my book. The minimum volume required is 0.2mL. I have always used IDEXX, although ASAP/Vetnostics has also just developed this assay.

We are very comfortable starting highly suspicious cases on treatment whilst awaiting definitive test results (usually they are already getting better before you get the result back).

Figure 1. Tray made up to do U/s guided FNA of lymph nodes and kidneys in cats with ‘dry’ FIPCase Report 1

C&T No. 5987

Introduction

Canine interdigital nodular pododermatitis is a common inflammatory condition affecting the pedal skin.1–4 Also known as pedal folliculitis and furunculosis or interdigital ‘cysts’, this multifaceted and complex disorder can prove frustrating to manage given the appearance is identical irrespective of the underlying cause. Secondary infection is a common consequence of pedal inflammation, often resulting in furunculosis (rupture of hair follicles) and subsequent formation of the classic nodules and draining tracts between the digits and pads. Methicillin-resistant staphylococci (MRS) are of global concern in veterinary medicine.5,6 MRS infections frequently present to veterinarians as pyoderma, wound infections and otitis externa due to methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus pseudintermedius (MRSP) in dogs.7–10 Deep pyoderma due to MRSP affecting the paws is not uncommon in the author’s practice and can prove difficult to resolve.

The use of therapeutic light (photobiomodulation) has experienced much interest in recent years and now represents a new and appealing management option for veterinary dermatological conditions.11 A novel approach to photobiomodulation is through application of a fluorescence light energy (FLE) system consisting of blue

light which activates a topical photoconverter hydrogel containing specialised chromophores (molecules able to be excited by certain wavelengths) that generate fluorescence. FLE has been demonstrated to ameliorate and cure superficial bacterial folliculitis,12 deep pyoderma,13 canine interdigital furunculosis,14 canine perianal fistulas,15 and cutaneous calcinosis.16 In such instances, FLE was responsible for a lessening in the length of antibiotic therapy (and time needed for healing) when administered as add-on therapy.

Herein we describe the use of fluorescence biomodulation as part of a multimodal treatment regimen in resolving a case of canine interdigital nodular pododermatitis complicated by MRSP deep pyoderma.

Bruno is a 3.5-year-old, 28.3 kg, neutered male English bulldog obtained from an Australian breeder as a puppy.

Bruno initially presented to the Veterinary Dermatology Clinic in late 2021 for management of relatively generalised pruritic dermatitis with a history of recurrent otitis externa and multiple episodes of superficial bacterial pyoderma responsive to courses of cephalexin. Age of onset of pruritus was at approximately 6-months of age. Pruritus was noted to affect Bruno year-round with repeatable ‘flares’ experienced each spring. No benefit was derived from a strict novel protein diet trial using the Prime100™ kangaroo/sweet potato roll. Pruritus was reportedly both steroid- and Apoquel®responsive. Bruno was up to date with core vaccines and Bravecto® spot-on for flea/tick prevention. Bruno was an otherwise systemically well dog with no known comorbidities. A diagnosis of canine atopic dermatitis was made based on history, examination findings and by elimination. Intradermal allergy testing was performed, and allergen-specific immunotherapy subsequently commenced, based on these results, in November 2021 and administered via the subcutaneous route. Physical examination at the initial appointment revealed no complicating infections and Bruno was reportedly comfortable across the trunk on Apoquel® (16mg once daily). Despite Apoquel®, mild-moderate pruritus affecting the ears and paws persisted for which twice weekly topical steroid therapy using Elocon® lotion was prescribed.

Bruno re-presented in January 2022 with a several week history of pedal pruritus and the development of ‘cysts’ between the toes on all paws despite diligent adherence to previously prescribed medications. Examination revealed diffuse furunculosis affecting the pedal skin across all paws (Figures 1-3). Cytological analysis of impression smears of haemopurulent exudate from draining tracts between digits revealed evidence of

chronic-active inflammation and intracellular diplococci consistent with interdigital nodular pododermatitis and complicating deep bacterial pyoderma. Trichography and deep skin scrapes from the paws were negative for demodectic mites. A swab of exudate was submitted to an external laboratory for aerobic bacterial culture and sensitivity. While awaiting results a tapering course of oral prednisolone (commencing at 20mg once daily) and topical Bactroban® ointment applied to all paws twice daily was commenced. Culture revealed heavy growth of Staphylococcus pseudintermedius resistant to all antibacterials tested except fusidic acid and rifampicin. Treatment options for management of extensively resistant staphylococcal deep pyoderma discussed with the client included systemic rifampicin and/or florescence biomodulation using Phovia®. The client elected the latter without the former, wanting to avoid possible rifampicin-induced hepatotoxicity. Phovia® was used per the manufacturer’s recommendations involving two, two-minute treatments of all paws once weekly. Phovia® was used in conjunction with oral prednisolone and topical mupirocin.

Bruno’s interdigital nodular pododermatitis with deep MRSP pyoderma resolved over a total of nine weeks of therapy without the need for systemic antibiosis (Figure 4). Comfort on the paws and pedal pruritus was greatly improved within the first two weeks of therapy. Repeat cytology was negative for diplococci at the recheck in week seven after commencing Phovia®; both Phovia® and Bactroban® ointment were continued for an additional two weeks prior to discontinuation. Atopica® 150mg once daily was instigated in week seven allowing for successful tapering and discontinuation of prednisolone over the following four weeks.

At time of writing, eight months after resolution of MRSP deep pyoderma on the paws, Bruno has remained comfortable without relapse of allergy signs including interdigital nodular pododermatitis. Atopica® has been tapered to a twice weekly frequency indicating response to allergen-specific immunotherapy with the view to discontinuing Atopica® altogether in the coming months and maintaining control of atopy with immunotherapy alone.

Resolution of deep pyoderma almost invariably requires the use of systemic antibiosis with topical therapy alone proving inadequate given insufficient penetration into the deep layers of skin to bring about microbiological cure. This case report describes the use of a novel intervention, fluorescence biomodulation (Phovia®), to resolve an extensively resistant staphylococcal deep pyoderma affecting the paws in an atopic dog without

the need for systemic antibiosis. The use of Phovia® allowed avoidance of a last-line antibacterial that can be associated with potentially fatal hepatotoxicity in dogs.

It is highly unlikely that such extensive MRSP deep pyoderma affecting the paws resolved in response to topical Bactroban®, prednisolone or allergenspecific immunotherapy indicating a pivotal role for Phovia ® in resolution of infection in this case. With the

ever-increasing prevalence of MRS infections seen by veterinarians it is crucial that we explore alternative treatments, such as Phovia ®, that can reduce reliance upon antibiotics.

Phovia ® technology includes a blue light-emitting hand-held LED lamp and a topical photoconverter gel. The gel contains chromophores (specialised molecules) that can absorb photons of directed light from the LED lamp and then re-emit them at different wavelengths in the form of fluorescence which, in turn, can manipulate the function of cells within the dermis and epidermis. Each wavelength has a discrete mechanism of action for resolving dermatitis, infection and improving skin regeneration. Phovia ® was a simple intervention that Bruno tolerated consciously on a weekly basis for the duration of therapy.

There is currently an evidence-base for use of fluorescence biomodulation for management of superficial and deep pyoderma,13 interdigital furunculosis,14 inflammatory disease of the canine interdigital skin. Lesions commonly become infected secondarily. In addition to management of the underlying cause, management of the chronic inflammatory changes in the interdigital skin created by secondary infection and by the release of keratin into deep tissues is required. Fluorescence biomodulation appears to modulate the inflammatory process in dermatological disorders and has shown promise in preliminary studies evaluating its use in superficial and deep pyoderma in dogs.

1. Bloom P. Idiopathic pododermatitis in the dog: an uncommon but frustrating disease. Vet J 2008;176:123–124.

2. Duclos D. Canine pododermatitis. Vet Clin North Am - Small Anim Pract 2013;43:57–87. Available at: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j. cvsm.2012.09.012.

3. Duclos DD, Hargis AM, Hanley PW. Pathogenesis of canine interdigital palmar and plantar comedones and follicular cysts, and their response to laser surgery. Vet Dermatol 2008;19:134–141.

4. Bajwa J. Diagnostic dermatology: canine pododermatitis. Can Vet J 2005;46:3. Available at: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/ PMC2834510/pdf/16454391.pdf.

5. Morris DO, Loeffler A, Davis MF, et al. Recommendations for approaches to meticillin-resistant staphylococcal infections of small animals: diagnosis, therapeutic considerations and preventative measures.: Clinical Consensus Guidelines of the World Association for Veterinary Dermatology. Vet Dermatol 2017;28.

6. van Duijkeren E, Catry B, Greko C, et al. Review on methicillinresistant Staphylococcus pseudintermedius. J Antimicrob Chemother 2011;66:2705–2714.

7. Ruscher C, Lübke-Becker A, Wleklinski C-G, et al. Prevalence of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus pseudintermedius isolated from clinical samples of companion animals and equidaes. Vet Microbiol 2009;136:197–201.

8. Duim B, Verstappen KM, Broens EM, et al. Changes in the population of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus pseudintermedius and dissemination of antimicrobial-resistant phenotypes in the Netherlands. J Clin Microbiol 2016;54:283–288.

9. Menandro ML, Dotto G, Mondin A, et al. Prevalence and characterization of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus pseudintermedius from symptomatic companion animals in Northern Italy: clonal diversity and novel sequence types. Comp Immunol Microbiol Infect Dis 2019;66:101331.

10. Little S V, Bryan LK, Hillhouse AE, et al. Characterization of agr groups of Staphylococcus pseudintermedius Isolates from dogs in Texas. mSphere 2019;4:e00033-19-.

11. Godine RL. Low level laser therapy (LLLT) in veterinary medicine. Photomed Laser Surg 2014;32:1–2.

12. Marchegiani A, Spaterna A, Cerquetella M. Current applications and future perspectives of fluorescence light energy biomodulation in veterinary medicine. Vet Sci 2021;8:1–11.

13. Marchegiani A, Fruganti A, Spaterna A, et al. The effectiveness of fluorescent light energy as adjunct therapy in canine deep pyoderma: a randomized clinical trial. Vet Med Int 2021;2021.

14. Marchegiani A, Spaterna A, Cerquetella M, et al. Fluorescence biomodulation in the management of canine interdigital pyoderma cases: a prospective, single-blinded, randomized and controlled clinical study. Vet Dermatol 2019;30:371-e109.

15. Marchegiani A, Tambella AM, Fruganti A, et al. Management of canine perianal fistula with fluorescence light energy: preliminary findings. Vet Dermatol 2020;31:460-e122.

16. Apostolopoulos N, Mayer U. Use of fluorescent light energy for the management of bacterial skin infection associated with canine calcinosis cutis lesions. Vet Rec Case Reports 2020;8:1–5.

17. Marchegiani A, Fruganti A, Bazzano M, et al. Fluorescent light energy in the management of multi drug resistant canine pyoderma: a prospective exploratory study. Pathogens 2022;11.

e. mvh@mudgeevet.com.au

C&T No. 5988

Introduction

Bangers is a 4.5kg 2-year-old-male intact (cryptorchid) miniature Dachshund from the Mudgee, New South Wales.

On Friday, 20th of May 2022, Bangers’ owner noticed a large wound on his inguinal/perineal area. The owner administered 3.0mLs of Benacillin intramuscularly into Bangers’ right hind leg.

Bangers presented to Dr Liam Ryan at Mudgee Veterinary Hospital on Sunday, 22nd of May 2022 with two severe necrotizing wounds. The larger wound extended from the lateral-scrotal region to the perianal area. The second, smaller wound was on the ventral abdomen, caudal to the prepuce and cranial to the scrotum. The wounds were swollen, fluid filled, cold to touch with extensive soft tissue involvement. Bangers was able to urinate normally. His body temperature was reported normal at 38.0°C.

Two open wounds of unknown origin. A white tail spider bite or a dog bite wound was suspected (Figures 1a & 1b)

22nd May 2022

Bangers received 0.2mL Metacam® SC 0.5mL Noroclav® SC, and 0.6 ml Entrotril® SC. The large lesion on the perineal area was flushed and lavaged extensively with sterile saline. The wound was packed with manuka honey and dressed. Bangers was taken home by the owner for observation overnight and continued on oral medication.

23rd May 2022

Bangers returned to Mudgee Vet Hospital for a bandage change. The wounds were debrided with saline and sterile swabs. Observationally, the amount of necrotic

tissue appeared larger, compared to the previous visit. The wounds were redressed with Manuka honey, wound facing Jelonet™, softban and an external layer of adhesive bandage.

24th May 2022

Bangers was admitted for another bandage change and reassessment. The wounds appeared stable in size and appearance, with absence of granulation tissue. The wounds were dressed as previously described.

26th May 2022

Bangers received his first session of back-to-back (2x2 minute sessions) Phovia® FLE light therapy to both wounds. The wounds were dressed as per previously described.

2nd June 2022

Bangers returned to Mudgee Vet Hospital for a bandage change and wound assessment. There was a dramatic improvement in the lesions.

Wound 1 received another back-to-back session with the Phovia® FLE light therapy. A manuka honey dressing was applied and Bangers was sent home.

Wound 2 treatments were discontinued after rubbing of the bandage prolonged the healing process. Phovia® FLE was discontinued on wound 2 and monitoring continued

9 th June 2022

Bangers returned to Mudgee Vet Hospital for reassessment of his wounds. Phovia® FLE light therapy was applied back-to-back, for the third and final week, to Wound 1. Wound 2 continued to be monitored as an open wound.

16th June 2022

Wound 1 was nearing clinical resolution therefore treatment ceased. Wound 2 remained open closing by secondary intention and no further treatment was applied.

Veterinary staff were happy with the speed of wound closure, noting the dramatic improvement from week to week. The larger wound healed faster than expected, after receiving Phovia® FLE back- to-back for 3 weeks. FLE is a promising and safe therapy for accelerating wound healing.

Non-invasive light therapy has been utilised in human wound management and is now being adopted into veterinary medicine. Phovia®, a new product from Vetoquinol Australia and New Zealand uses a unique

Figure 1a & 1b. Wounds 1 and 2—22nd May 2022

Figures 2a & 2b. Bangers receiving Phovia® FLE light therapy to both wounds. The wounds were dressed as per previously described.

Figure 3 & 4. Show wounds on the 9th June 2022

4 3

2b

1b 2a

1a

Figure 1a & 1b. Wounds 1 and 2—22nd May 2022

Figures 2a & 2b. Bangers receiving Phovia® FLE light therapy to both wounds. The wounds were dressed as per previously described.

Figure 3 & 4. Show wounds on the 9th June 2022

4 3

2b

1b 2a

1a

chromophore gel and a blue light-emitting diode (LED) lamp to halve skin disorder recovery times, reducing antimicrobial use. The blue light activates the gel, generating polychromatic fluorescent light energy (FLE). The overall result is reduced inflammation, accelerating dermal fibroblast proliferation, increasing collagen synthesis and angiogenesis. Appropriate use of FLE can accelerate regeneration of damaged skin and improve wound healing time. The primary clinical protocol of FLE consists of 2 x 2-minute light therapy sessions weekly (back-to-back protocol) until clinical resolution.

Phovia® manipulates the function of cells within the dermis and epidermis, to reduce inflammation but still accelerate regeneration.

Different tissues absorb different wave lengths

Overall effect in an increase in mitochondrial cellular energy production

By stimulating natural chromophores within cells (especially within mitochondria), the efficiency of the mitochondrial electron transport chain can be increased, accelerating healing, cell repair, and cell division² Free radicals may also be reduced

Using polychromatic FLE is clinically proven to accelerate natural skin regeneration, even in situations where there is significant and deep skin damage³

The effects are anti-inflammatory, target bacteria, accelerate dermal fibroblast proliferation, increase collagen synthesis and stimulate angiogenesis

There is also solid evidence that FLE can accelerate healing of chronic inflammatory skin conditions and acute and chronic wounds in humans⁵ and dogs⁶

The Phovia® system triggers multiple cellular responses simultaneously.

Cost depends on the amount of Phovia® gels used and duration. As a guide, the lamp is ~$850 (cost price to vet, ex GST) and the lamp life lasts for 19,980 x 2-minute sessions.

The gels are ~$25 per pot (at cost price) the size of the wound will determine how many are needed.