Produced by the students at the Walter Cronkite School of Journalism and Mass Communication at Arizona State University

A project funded by the Howard G. Buffett Foundation

Produced by the students at the Walter Cronkite School of Journalism and Mass Communication at Arizona State University

A project funded by the Howard G. Buffett Foundation

For this project, student reporters spent two semesters studying the issues involved and spent eight days on the ground reporting from Puerto Rico, where they were led and guided by Cronkite School faculty members.

“Puerto Rico: Restless and Resilient” was made possible by a grant from the Howard G. Buffett Foundation, the Illinois-based nonprofit organization founded by the international photojournalist, author and philanthropist.

Faculty members

Rick Rodriguez is the former executive editor of the Sacramento (California) Bee and the Southwest Borderlands Initiative professor at the Cronkite School, where he teaches courses on Latino issues, ethics and depth reporting.

Jason Manning is the director of Student Media at Arizona State University and a professor of practice at the Cronkite School, where he teaches courses on digital technology and reporting.

Creative director

Linda O’Neal Davis

Digital production

Bhuvan Aggarwal

Lori Todd

Student reporters

Brianna Bradley

Aydali Campa

Brendan Campbell

Mersedes Cervantes-Arroyo

Claire Cleveland

Renata Correa Cló

Cariño Dominguez

Andres Guerra-Luz

Carly Henry

Johanna Huckeba

Sydney Maki

Amanda Mason

Jennifer Miller

Ben Moffat

Lerman Montoya

Tyler Paley

Olivia Richard

Charlene Santiago

Ryan Santistevan

Overcoming landfall

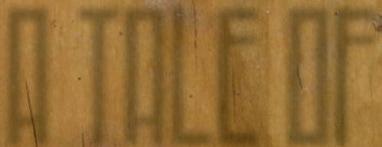

A tale of two towns: Puerto Ricans rebuild with hope for a brighter future

Arizona State University professor’s “teach in the dark” lessons connect

Puerto Rico school turns adversity into strength after Hurricane Maria

The tale of two schools and their path to recovery

Family struggles to care for daughter in wake of Puerto Rico power outages

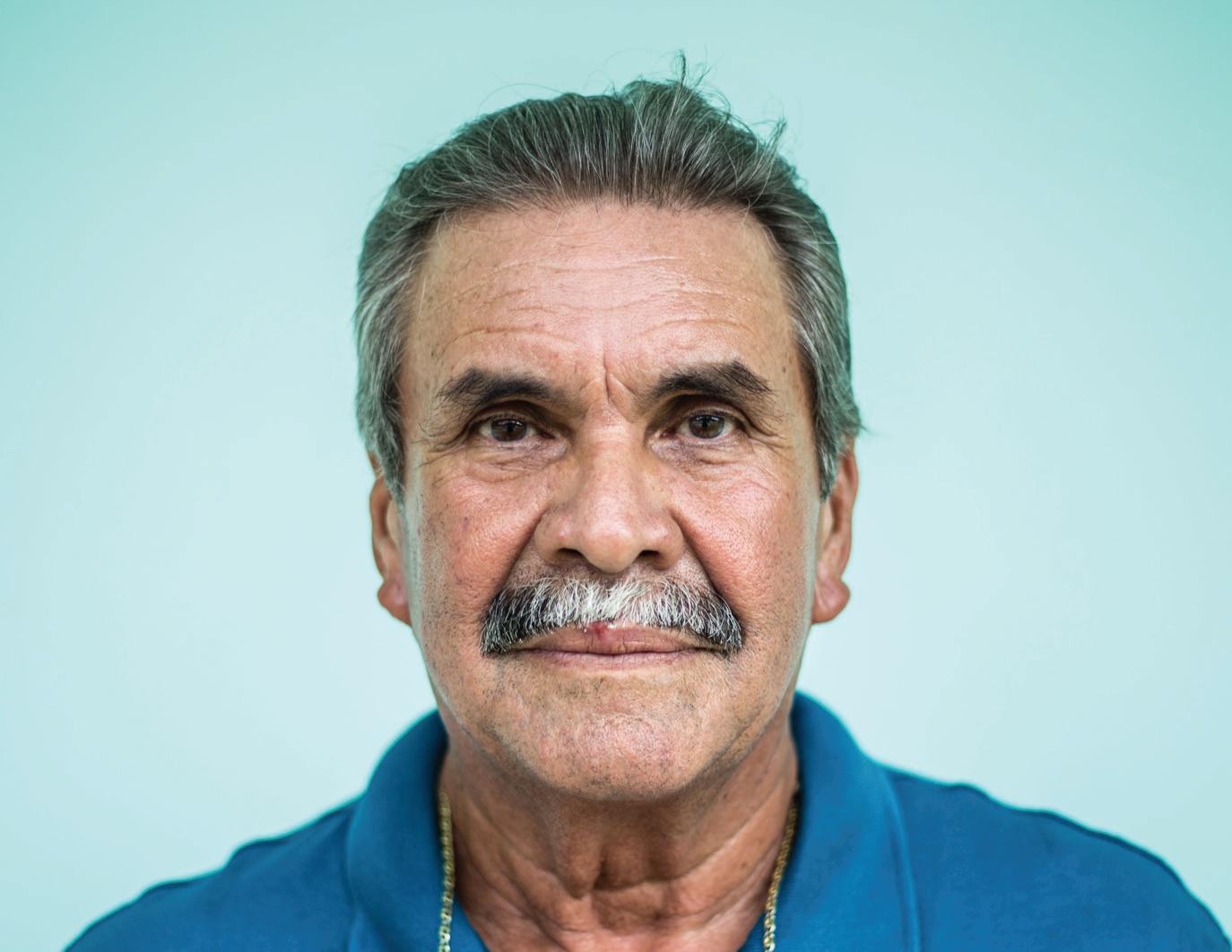

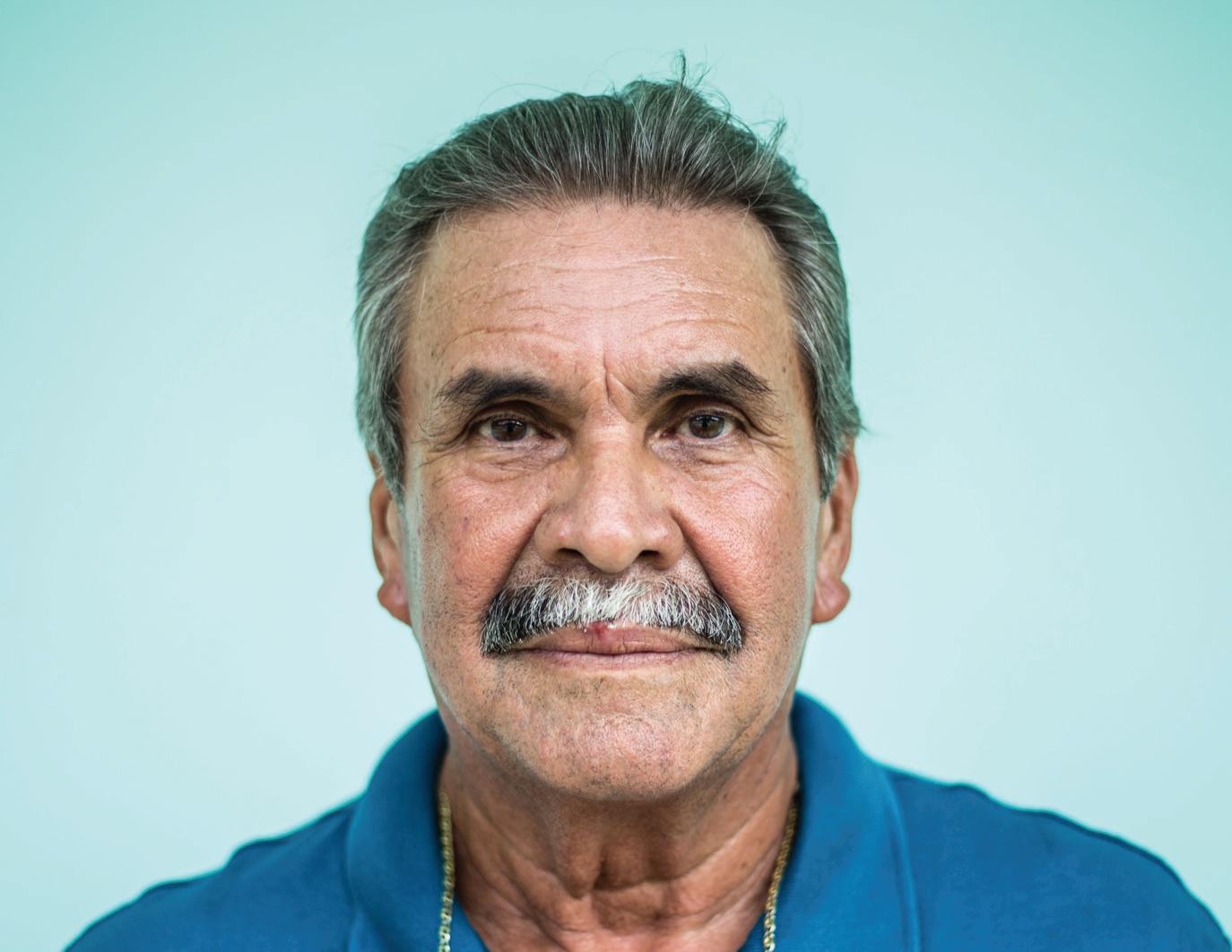

Portraits: mountain communities coping with the aftermath

Hurricane provides opportunity for Puerto Rico’s battered tourism industry

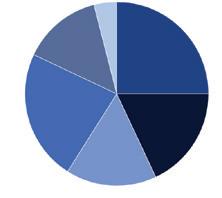

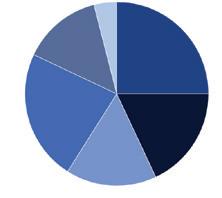

Puerto Rican retirees face uncertainty on pension cuts after hurricane

Without researchers or funds, Puerto Rico universities grapple with future after Hurricane Maria

Puerto Rico’s push for food independence intertwined with debate over statehood

On the cover: Auria Sanchez looks at her partially destroyed home where she lives with her husband in Yabucoa, Puerto Rico. Six months after the landfall of Hurricane Maria, the home still had no electricity or running water and its only roof was a blue tarp provided by FEMA.

Photo by Ben Moffat

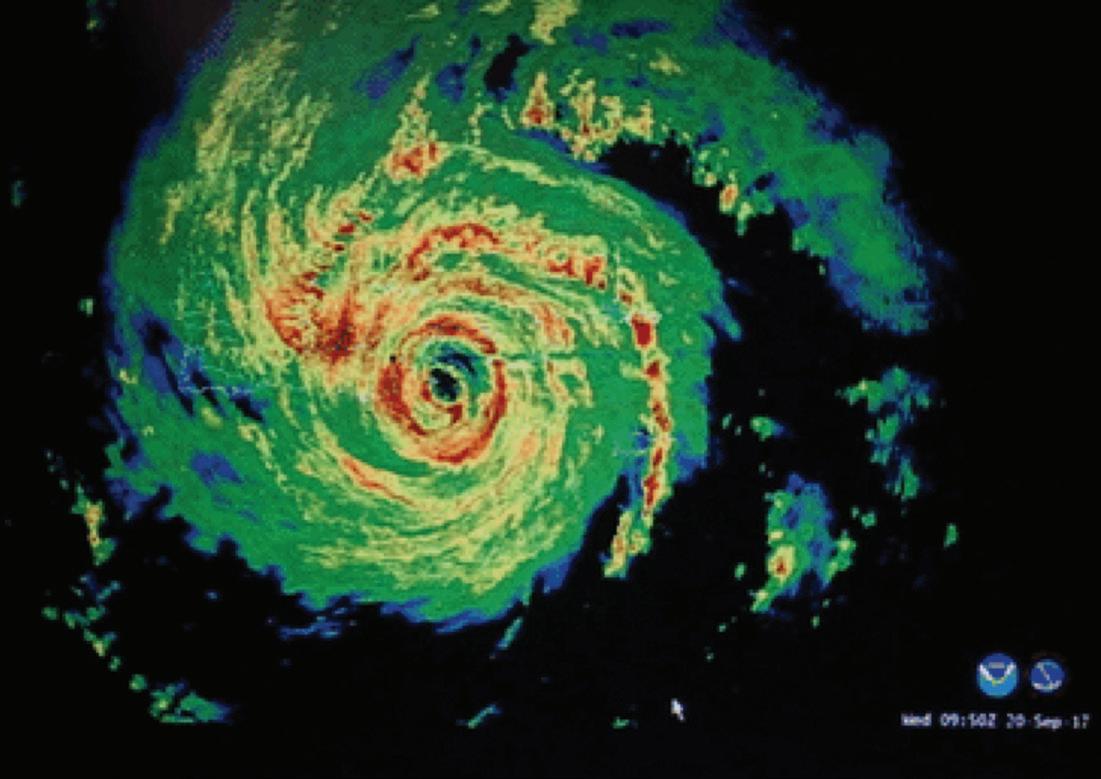

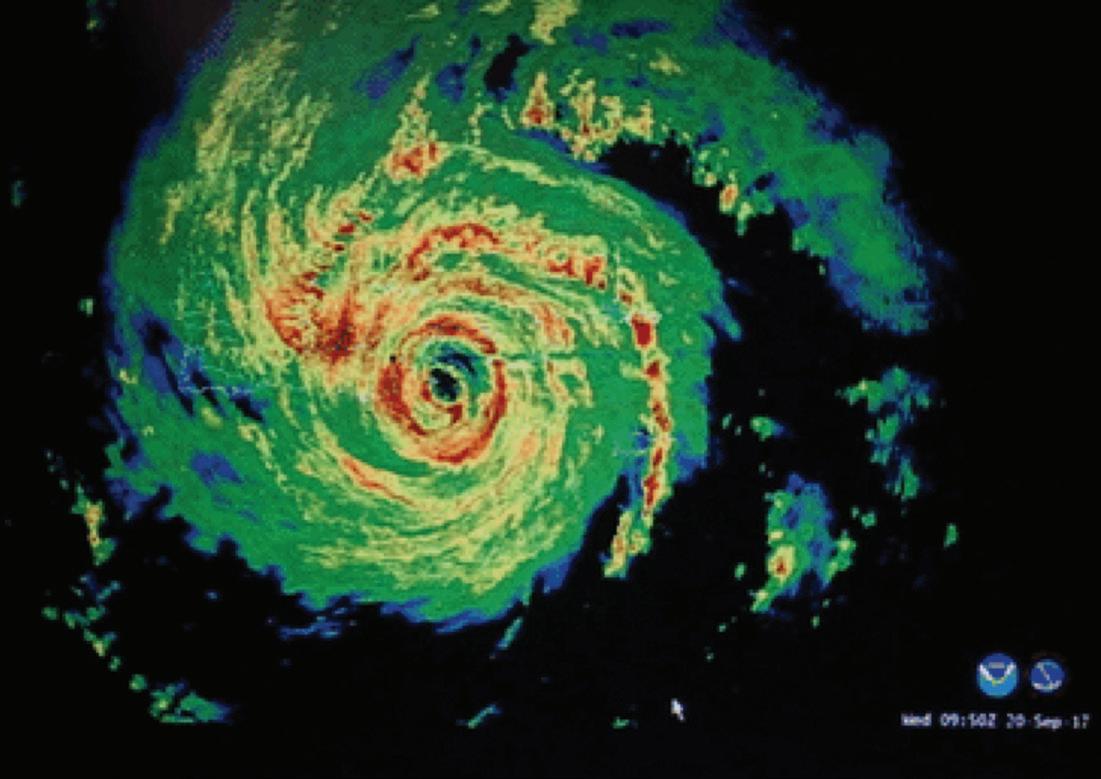

On Sept. 20, 2017, the U.S. territory of Puerto Rico was devastated by the most powerful hurricane to hit the island in 85 years, leaving its 3.6 million residents – the vast majority of them U.S. citizens – without power or potable water and with severely damaged infrastructure and little hope for a quick recovery.

When Maria hit, the island was already reeling.

Just two weeks earlier, Hurricane Irma had crashed the outdated electrical grid, leaving 1 million customers without power. Maria took out another 500,000 and ensured that the restoration of power would take months and for some, even a year.

Puerto Rico’s government, the island’s largest employer, already was fighting off bankruptcy and considering jobs cuts and reducing pensions. A severe recession that began in 2006 had spurred an exodus of tens of thousands of Puerto Ricans to the mainland of the U.S. and, four months before Maria hit, had forced the closure of 165 public schools.

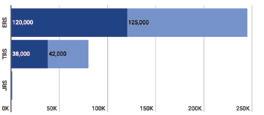

It is against that backdrop that 19 graduate and undergraduate students of the Walter Cronkite School of Journalism and Mass Communication at Arizona State University traveled to Puerto Rico during March 1-9, 2017, to assess recovery efforts six months after the storm. The project, directed by Cronkite professors of practice Rick Rodriguez and Jason Manning, was supported by an endowment from the Howard G. Buffett Foundation. What the students found and documented in videos, photos and words was that large segments of the island were still in dire straits. An estimated 50,000 to 100,000 U.S. citizens were without power six months after the hurricane. While larger urban areas like the capital city of San Juan had returned to a semblance of normalcy, many residents of small towns along the coasts and in the mountainous central regions were still lacking basic services and living in homes with blue tarps for roofs while struggling to reopen schools and businesses and rebuild their homes. For some, like Martha Rivera, the power outage in the mountainous Ciales region was a nightly nightmare. For more than six months, she worried that she would awaken to find that an old generator had failed, leaving her 23-year-old daughter, Melissa, without her life support system.

“My biggest fear is that I stay sleeping and when I wake up, she is not breathing anymore,” Martha Rivera said in Spanish. “That is why I don’t sleep. I don’t sleep because that brings me fear; that I get up and see she’s not breathing.” Fortunately, power to their house was restored after nearly seven months.

In Yabucoa, at the southeastern end of the island where Hurricane Maria first made landfall, many of the residents remained without power six months later, forcing them to live with relatives and struggling to move on. “You see houses totally destroyed, families crying because they had lost everything. It is an experience that truthfully you will carry for the rest of your life,” said Mayor Rafael Surillo.

But Surillo said the struggle also has brought the community closer together. “I can honestly guarantee that I feel even more proud to be mayor of this town,” he said.

Amid the reports of damages that have reached nearly $100 billion, of hurricanerelated deaths which, months after our visit, were reported to have reached nearly 3,000, of the 135,000 residents who, according to Hunter College, left for the mainland U.S. in the wake of the hurricane, the Cronkite reporters found many public officials and ordinary citizens who echoed Surillo’s sentiments.

They found a determined, resilient populace: children returning to school and pledging allegiance to their homeland; doctors working to help those in need; neighbors helping neighbors; volunteers from the mainland U.S. helping to rebuild; and government workers trying to overcome bureaucratic roadblocks to deliver much needed food, health care and service.

What they found is documented in “Puerto Rico: Restless and Resilient” presented here and online, including video in English and Spanish, at cronkitenews.azpbs.org/2018/puerto-ricorestless-and-resilient/

Puerto Rico : Restless and Resilient

Yabucoa, a small town 46 miles southeast of San Juan, bore the brunt of Hurricane Maria’s strongest winds, according to meteorologists. The National Weather Service reported that Maria had made landfall in the town with maximum sustained winds of 155 mph.

1 Puerto Rico : Restless and Resilient

Charlene Santiago and Ben Moffat | Cronkite Borderlands Project

YABUCOA, Puerto Rico – It was 6:15 a.m. on Sept. 20, 2017, when Hurricane Maria made landfall in this municipality of 34,000 at the southeastern tip of the island.

The power of the Category 4 hurricane – the first to hit Puerto Rico since 1932 – was immense: 155-mile per hour sustained winds, tornadoes and ocean swells resulting in nearly $100

billion in destruction across the island.

The government in August said that nearly 3,000 people died from Hurricane Maria – either from the hurricane itself or from its immediate aftermath. Officials had initially put the toll at 64. The revised totals attributed the high mortality rate to the interruption of medical care. The hurricane had damaged

roads, affected the water supply and knocked out electricity and telecommunication networks. Six months after the hurricane, Yabucoa, where the hurricane struck first, was still struggling with power outages and with the uncertainty of whether destroyed homes, businesses and lives could ever be rebuilt. Here are some of the residents whose lives have been changed:

Map data ©2018 Google

Puerto Rico : Restless and Resilient 2

María Carrasquillo, who lives in the Limones section of Yabucoa, said she has gotten used to the darkness while she waits for services to be restored.

3 Puerto Rico : Restless and Resilient

Photo by Charlene Santiago

For more than 15 years, Irma Arroyo has been an anchor for her son George after he suffered an accident. They continue the battle against his disabilities, but now without electricity.

Puerto Rico : Restless and Resilient 4

Photos by Ben Moffat

5 Puerto Rico : Restless and Resilient

Since Hurricane Maria, more than 135,000 Puerto Ricans have left the island, according to the Center for Puerto Rican Studies at Hunter College in New York. The Colón-Santiago family is determined to stay and slowly recover, even though Hurricane Maria left them with almost nothing.

Puerto Rico : Restless and Resilient 6

Photos by Ben Moffat

7 Puerto Rico : Restless and Resilient

“Ninety percent of the municipal buildings were destroyed. That made us very sad, but even sadder was when we went into the communities,” said Rafael Surillo, mayor of Yabucoa.

Puerto Rico : Restless and Resilient 8

Saturday, March 3, 2018, at Iglesia Ciudad de Reino in Yabucoa, Puerto Rico. After a service in the parking garage, church volunteers distributed food, diapers, fl ashlights and other aid to community members. Photos by Ben Moffat

9 Puerto Rico : Restless and Resilient

Saturday, March 3, 2018, at Iglesia Ciudad de Reino in Yabucoa, Puerto Rico. After a service in the parking garage, church volunteers distributed food, diapers, fl ashlights and other aid to community members. Photos by Ben Moffat

Puerto Rico : Restless and Resilient 10

11 Puerto Rico : Restless and Resilient

COROZÁL, Puerto Rico – This is a tale of two communities, 8 miles apart – separated by winding roads but divided by more than geography.

The stark contrast isn’t solely because of Hurricane Maria. Corozál is a municipality of 37,000 with a large middle class and neatly kept concrete homes that mostly withstood the storm’s 155-mph winds last September.

Villa Esperanza, in nearby Toa Alta, is a squatter community where residents years ago began building homes on vacant land out of scraps and wooden planks.

Maria blew away those makeshift structures and knocked out the community’s gerry-rigged utilities. Before the hurricane, there were

132 households in Villa Esperanza (Hope Villa in Spanish); about 70 remain.

But residents there and in Corozál have responded in similar ways, demonstrating a spirit of resiliency evident in hard hit communities all over the island.

That spirit is reflected in the actions of Jorge Olivo, a resident and community leader of Villa Esperanza. In the hours before and during the hurricane, Olivo stayed with four other people under the concrete bleachers of a local stadium. He could have fled with his family to safety outside the squatter town, but he stayed to make sure the others were safe.

Olivio said most Villa Esperanza residents stayed at a

Puerto Rico : Restless and Resilient 12

Ryan Santistevan | Cronkite Borderlands Project

The home of Michel Rodriguez was devastated in the hurricane. The upper level no longer has a roof, allowing vines to creep in from above. Photos by Ben Moffat center, “but since some people chose to stay here, like two or three families stayed, that’s why we chose to stay there – in case we needed to help them, I wasn’t going to let anything happen to them.”

Maria devastated his home; only his kitchen stands. He now peers out at Villa Esperanza through empty spaces that were his bedroom and living room before they were blown away.

In Corozál, the neighborly spirit is reflected in the work of Nery Luz, director of the Municipal Office for Emergency Management. The mother of two small children, she has spent many long days and uncounted extra hours responding to hurricane victims.

On a March day, six months after the hurricane, tears welled in Luz’s eyes as she talked about how much more needs to be done for Corozál.

“Unfortunately, we’re still handling the

situation,” Luz said. “Not because today we dress a little better and do our makeup does that mean everything’s fi ne. It’s every day that someone comes here; it’s a daily thing.”

The rebuilding of Villa Esperanza poses an opportunity for the Puerto Rican government: to legitimize the legions of people who have built small homes on vacant land or who have no proof the land they live on is theirs, passed down through generations with no deeds recorded. Several Puerto Ricans interviewed by Cronkite News said they couldn’t qualify for federal aid to rebuild because they couldn’t prove ownership.

Fernando Gil, secretary of Puerto Rico’s Department of Housing, said that in the wake of Maria, 48,000 deeds have been given to squatters. That’s a start, advocates say, but far short of meeting the island’s needs. There have been estimates

of 1 million squatters living on the island, a number Gil refutes.

“I don’t buy that amount of people living in squatter communities or informal housing,” he said. “I mean probably more than 70 or 80 thousand people or less, but a million? That’s a lot of people.”

Villa Esperanza residents know they aren’t a priority for repairing power lines, so they’ve taken it upon themselves to climb up the poles to gerry-rig their utilities.

Still, residents like Maria Ortiz, who has lived in Villa Esperanza for four years, say they would rather return to the storm-damaged squatter community they consider home than rent in another location.

When the hurricane was bearing down on the island, Ortiz and other residents sought shelter in a school down the road. She stayed for three weeks but struggled

there. She said tensions boiled over in the close quarters but she tried to mind her own business in hopes of returning home.

When she fi nally returned for the fi rst time to where her home once stood, she said it was a lot harder than she thought it would be. Only the floor remained.

“It’s not the same saying it and seeing it,” Ortiz said. “Every single house was gone, we had nothing, and I still get sad. I get sad for at least 10, 20 minutes” every day.

Her neighbors helped her put up four makeshift walls to allow her to move back in. She used a gasoline generator to power what was left of the home. It cost $20 every two days to keep it going. Fortunately, her electricity was restored a month ago.

Ortiz was among the lucky squatters who received government aid. She said the Federal Emergency Management Agency

13 Puerto Rico : Restless and Resilient

Opposite page: Maria Ortiz’s daughter was a pastor at a local church before losing everything in Hurricane Maria. She was forced to move her family to New York. Ortiz keeps a statue of the Virgin Mary as a daily reminder of her daughter. Photo by Carly Henry

gave her $25,000 to repair her home after a group of pro bono lawyers explained the documentation needed to qualify.

With the help of her son Peter, Ortiz is building her home out of concrete, to better withstand future storms. She hopes someday to build a restaurant on another part of her land.

“I think Villa Esperanza is going to get better, I’ve seen the people and they want to be better,” Ortiz said. “Naturally, I have a lot of faith; I always think it’s possible that I can do it. Ever since I was a little girl, I know I can do it. I know I’m going to see my house. I know God is going to give me the time to see my house again.”

Another Maria Ortiz lives about a half hour away in Corozál. Although they share the same name, their lives are as different as the communities in which they live.

The home of this Maria Ortiz sits low against the mountainous terrain near Rio Corozál. She lives alone; her husband died a few years ago. Emergency responders say the houses on her block were underwater because the river topped its banks.

Ortiz’s demolished home, made of wood, stood out from neighboring concrete houses, which were mostly intact. Her roof and floor remained but the walls and furniture were gone.

Friends and family assumed Ortiz would be the most heartbroken, she said, but it was her daughters who were most torn. Their childhood home, full of memories, had been taken from them. They are helping Ortiz and her brother rebuild the home, but they can’t get back the history.

She said FEMA did help her, but only enough to buy materials, not to do the work. She could apply for aid from Tu Hogar Renace, a government program designed to repair homes so they are safe, but Ortiz said the process required too much documentation.

“I haven’t looked for it, because since I have the help of my family, I think that maybe there’s other people that don’t have the help of their family, and that resource could be for them,” she said.

Ortiz doesn’t have to sleep alone in a dark room of wooden walls, like her counterpart in Villa

Esperanza. Her daughter wouldn’t let that happen, so Ortiz stayed with her in a home up the hill. For the past three months, her brother has helped her rebuild a little each weekend – with concrete, this time.

She misses her privacy most of all.

“I’m crazy (ready) to be back home. Even though I’m good with my daughter, it’s not the same as someone’s own home,” Ortiz said.

Gil, the housing secretary, said Tu Hogar Renace (Your Home Is Reborn in Spanish) provided through Puerto Rico’s Department of Housing and FEMA, helps pay for restoration of electrical service, repairs to roofs, walls and windows as well as removing debris.

“Obviously it’s kind of hard to get like some of the materials … due to availability, but we’re in the process of getting new providers and the current providers like to make it happen,” Gil said.

Luz, Corozál emergency manager, said the town slowly has been rebuilding.

“I feel like in a way we are forgotten, but at the same time, I understand,” Luz said. “It’s not that the event just happened in Corozál. You have 77 other municipalities that went through the same thing.”

Every day for months, Luz said, someone would come to the steps of her agency’s office seeking help, including people who had lived in their cars until they couldn’t anymore. The need for assistance has slowed since Maria, she said, but it’s persistent.

The power of the people is what will save Puerto Rico, she said.

“This is the opportunity that Puerto Ricans have, to rebuild an entire country,” Luz said. “It’s not the government. It’s the people, the individuals.”

About 10 minutes from the heart of Corozál, Michel Rodriguez, her husband and 5-year-old son, both named Joseph, also are rebuilding their lives. Their dog, Sparky, sits leashed in front of the abandoned school they broke into and where they’ve lived since fleeing a refugee center after the hurricane destroyed their home.

“At the refugee center, men and women were using the same restroom, and no one assured me

Above: Jorge Olivo looks out at the Villa Esperanza neighborhood from the foundation of the home he is building.

Puerto Rico : Restless and Resilient 14

Below: Many homes in Villa Esperanza have been reconstructed with wood. If another hurricane comes, these wooden homes could be destroyed. Photos by Carly Henry

Michel Rodriguez, her husband and their 5-year-old son, Joseph, moved into an abandoned school building after their house was destroyed by Hurricane Maria. Sparky (left), the Rodriguez family’s terrier mix, stands outside the abandoned school where they live in Corozál, Puerto Rico. Just down the road from their house, the building had been abandoned for years before the family moved in after Hurricane Maria in September 2017.

“It’s not enough, but in a way it’s enough because the important thing is we’re still a unit as a family, and at least we have food on the table,” she said. “That’s all we need.”

The family spends $100 on water every two weeks. Her husband takes odd jobs when he can to support them, but he’s unemployed.

Rodriguez considered buying ice with her remaining $2, but the next morning decided to buy her son breakfast before school. It’s a choice most Americans don’t usually face, but she’s undaunted.

15 Puerto Rico : Restless and Resilient

Above: Joseph Rodriguez brushes his teeth in the boys’ restroom of the abandoned school and Michel watches Joseph ride his bike after getting him dressed for kindergarten at the nearby still-operating Escuela Abraham Lincoln. Photos by Ben Moffat

“I want a family that’s even more united,” Michel Rodriguez said. “And I know that if I leave, my family will fall apart, because at the end of the day the woman is an important part of the family, and not even just the woman, but the mother, and that’s what I want for the future, and with the will of God we’re going to achieve it.”

Puerto Rico : Restless and Resilient 16

the safety of my son, and since we knew that this school was abandoned, we decided to break the locks and come here two days after Maria,” Michel Rodriguez said.

Going back still isn’t an option – a huge tree branch blocks the steep walkway to the family’s two-story home, which has no roof. A pan remains on the stove, as if the storm interrupted dinner that night. A twin-size mattress sits on the floor in the bedroom, waterlogged. Toys lie scattered about.

The family spends $100 on water every two weeks. Her husband takes odd jobs when he can to support them, but he’s unemployed.

Rodriguez considered buying ice with her remaining $2, but the next morning decided to buy her son breakfast before school. It’s a choice most Americans don’t usually face, but she’s undaunted.

“I find strength in the way I was raised; they raised me strong,” Rodriguez said of her family. “I come from a woman that raised us as a single mother, and I know that you have to work hard to raise a child, and the way I am relieves me a bit of the stress of everything.”

Rodriguez said they hope to move back to their house sometime soon – a tall order, considering the roof is missing.

To deflect from her family’s living conditions, she uses humor to get her through the day. Her exuberant son follows her lead, posing after getting dressed for school.

As the communities rebuild, Puerto Ricans worry about the next big storm.

According to the Puerto Rico Department of Housing’s standards, a home must be able to withstand 140 mph winds. But Secretary Gil said it’s hard for the government to ensure that homes, especially those within squatter communities like Villa Esperanza, meet this standard. That responsibility lies with the owner of the property, he said.

The consensus of everyone interviewed for this story is that Puerto Rico is not ready for the upcoming hurricane season, which begins June 1 and runs through the end of November. Gil said the infrastructure is old and the electrical grid dates to 1952, adding that the department is working with renewable energy for more reliable power sources.

“It’s sometimes like even difficult to remember these five months,” Gil said. “But it’s something that every day we wake up with the sense that, and with the security that we are going to leave something better for our kids, grandkids and for the future generations.”

Despite all her misery, Maria did some good, Luz said. People who never interacted with their neighbors suddenly were giving

their last bottle of water to the strangers next door.

“I think that Maria came to teach us that we’re vulnerable, but at the same time we’re strong. … We had our damage and loss to know that there’s families that lost their homes of 30, 40 years, and they lost it in a second – Maria took it,” Luz said. “But people have a lot of willpower and faith to keep going and rebuild.”

Maria Ortiz received money from FEMA to help rebuild her home. Photo by Carly Henry

Above and opposite page: Michel Rodriguez, her husband and their 5-year-old son, Joseph, moved into an abandoned school building after their house was destroyed by Hurricane Maria. Photos by Ben Moffat

During Hurricane Maria, Jorge Olivo spent 10 hours inside of the concrete portion of a local stadium with four community members who did not want to leave the area. Photo by Carly Henry

17 Puerto Rico : Restless and Resilient

“I find strength in the way I was raised.” — Michel Rodriguez

Arizona State University professor’s ‘teach in the dark’

connect communities after Hurricane Maria

AGUADA, Puerto Rico – Manuel Aviles-Santiago talks on the phone with his parents in Puerto Rico every day, sometimes twice.

On the day Hurricane Maria hit in September 2017, he made his usual call to his mother before teaching his class at Arizona State University.

Then the nightmare began, and the phone stopped ringing. Radio silence.

Separated by thousands of miles with no way to communicate, Aviles-Santiago wondered how his family had fared after the hurricane left thousands of Puerto Ricans without power or shelter.

Reports on damage from major cities rolled in, but there was little information from less-populated areas, like his hometown Aguada, a small city on the island’s western coastal valley.

After two weeks of sleepless nights and scouring the internet for updates, Aviles-Santiago, an assistant professor of communication and culture, had an idea for his Introduction to Human Communication class.

“I’ll be teaching my class with the lights off – with no use of technology – in order to create awareness about the humanitarian crisis of Puerto Rico,” he posted on Facebook before heading to his evening class on Oct. 4, 2017. “Teaching in the dark for Puerto Rico.”

He slipped into the classroom without turning on the lights and, without explanation, left his students in the dark both literally and figuratively.

“It was a really interesting dynamic because the students didn’t question anything,” Aviles-Santiago said. “They just listened. They had to put a little bit more effort into listening because there were no visual components, and I had to put in a little more effort myself in teaching.”

He spoke about the situation – both his and the island’s – and later described the class as a humbling, “beautiful dynamic.” His main goal, he said, was to spark a conversation and make a distant, yet serious, issue become real to his students.

“For a long time, people didn’t understand what Puerto Rico was,” he said. “I think that now with this unfortunate situation, people are getting more interested in Puerto Rico. … (They’re) learning now that Puerto Ricans are U.S. citizens. I get that question a lot: ‘Are you here with a visa?’ or ‘How does that work?’”

At the end of the class, he explained the darkened classroom. The students asked more questions.

“They wanted to get more involved,” he said. “They

lessons

Puerto Rico : Restless and Resilient 18

Johanna Huckeba | Cronkite Borderlands Project

sent me emails asking how they could help, and I encouraged them to promote visibility, which I think is so easy to do, especially with social media, and it doesn’t cost anything. So that’s what they did.”

Students took to social media, using variations of the hashtag #TeachingInTheDarkForPuertoRico and sharing photos of themselves using only candlelight.

“Having class in the dark really did bring it home for a lot of us because you don’t always think about how your education is a privilege,” said Madelyn Sugg, a sophomore business communication major. “These are other kids who are just trying to get the same education we’re trying to get.”

While Aviles-Santiago made the best of his situation in Arizona, his family was in survival mode in their small, elevated home on the east coast of the island.

The mind of his father, Jesus Aviles-Perez, was already ticking the night before the hurricane struck. The power already had been disconnected from their small town.

His father boarded up the windows and set up a funnel running from the roof to the backyard pool to collect water from the storm to use for plumbing. He pulled out an unused propane tank and a small stovetop to prepare meals, most of which came out of cans of chili and corned beef.

The family and their home physically weathered the storm. The intense winds did break an antenna, which sat crumbled on the rooftop, and left imprints of leaves that had lashed the walls. But emotionally, they faced ongoing challenges.

The loss of communication with their two sons living in mainland United States was especially difficult for Doris SantiagoVillarrubia, who was accustomed to speaking with them every day. She knew they would be concerned about the family, but she also worried about their own well-being.

Some days, she said, it was all she could think about.

“I got really skinny, because I couldn’t eat, I couldn’t sleep,” Santiago-Villarrubia said.

It took two weeks to make contact. SantiagoVillarrubia’s cousin was the fi rst in the family to speak to the sons in Arizona and Texas after fi nding an old landline phone and discovering the telephone cables survived the brutal winds.

With cell phone service still down, her cousins’ home across the street quickly became a hub for calling distant loved-ones.

When Doris Santiago-Villarrubia made the fi rst call, hearing her son’s voice cutting in and out of her spotty connection, she cried tears of joy and relief.

But that connection didn’t last long. Just a few days later, a Federal Emergency Management Agency truck drove down their street, accidentally ripping down the landline cables. In the next few weeks, they again endured the silence.

Armed with the knowledge his family was physically safe, Aviles-Santiago refocused on his awareness efforts in the states. His original post about the classroom exercise gained traction on Facebook. Across the U.S., people commented on his efforts. Other professors tried it with their own students.

Jonathan Montalvo, an assistant professor of Spanish at Graceland University in Lamoni, Iowa, was among them.

Montalvo, also from Puerto Rico, taught in the dark with his three classes. Like AvilesSantiago, he’d lost touch with his family after the storm.

“My motivation was, not only because I saw Manuel doing it, but because I was also affected personally by (Hurricane Maria), so I just wanted to create awareness,” he said.

The movement continued to grow in October when Aviles-Santiago wrote about his work for Puerto Rico’s largest paper, El Nuevo Día. The story circulated online, but with most of the island without power or internet access, it was the print copy of the story that caught Melba Passapera’s eye.

Passapera, a bilingual teacher in Cidra, Puerto Rico, cut the article out of the newspaper and showed her colleagues because she was so moved

by Aviles-Santiago’s project. His words, she said, motivated her “during those dark days.”

“I agreed with him 100 percent,” she said. “The only way that we, as an island that was so badly hit by this hurricane, are only going to be able to get up on our feet and start over again, is through education.”

Passapera asked her mother, who was visiting Arizona at the time, to contact Aviles-Santiago. Meanwhile, she went to work, preparing for her students to return.

After her mother reached Aviles-Santiago, a collaboration was born.

Passapera compiled a list of supplies she needed, including desks, chairs, books, games and art supplies, and she sent it to AvilesSantiago.

Aviles-Santiago spread the word to collect supplies.

In November, the students returned to the hallways of Passapera’s school.

On their fi rst day back, Passapera stood in front of her students and read Aviles-Santiago’s article, and she instructed them to write letters to the island, entitled “Dear Puerto Rico.”

The students described their experiences of Hurricane Maria, but they focused mainly on their hopes for the future of their home.

One of Passapera’s former students also took part, saying “my Puerto Rico is the beautiful smile of the child whose home was taken by Maria.”

“The fact that so far away, in Arizona, he’s teaching these students that maybe don’t know about us to be sympathetic with what happened to us,” 16-year-old Diomarys Garcia Cardona said. “I’m very glad he did that.”

Months later, Aviles-Santiago flew home over his winter break. As the plane coasted over the island, the blue tarps lining the streets struck him. This place was different than the home he once knew.

When he reunited with his family, he said he could see the emotional toll the hurricane took on his parents.

“It really frustrated me and struck me to see that. I felt that they aged throughout this process,” he said. “They looked tired and worried about the next hurricane season. They cannot stop thinking about it.”

19 Puerto Rico : Restless and Resilient

Manuel Aviles-Santiago, assistant professor of communication at ASU, taught classes in the dark to show support for the people of Puerto Rico who were without power after Hurricane Maria.

CIDRA, Puerto Rico – Hurricane Maria took Principal Debra Angie Hernandez’s father, but she was determined it wouldn’t take her school.

Just days after the hurricane struck, Hernandez and teachers such as Melba Passapera and parents such as Hilda Marina Santos sprang into action to make sure the Luis Munoz Iglesias K-12 school would not become another of the storm’s victims.

The specialized bilingual school had just

been freshly painted a month before the violent winds of Maria arrived on Sept. 20, 2017. It was quiet in the days that followed: The roads were too dangerous to navigate, and the Department of Education hadn’t greenlighted anyone to step onto school campuses.

Six days after the hurricane struck the island, Passapera turned on the radio to hear an announcement from the department calling on school staffs to visit their campuses to assess damage.

The image of what they found – a field of fallen trees, mounds of mud, flooded classrooms and downed electrical wires –was still seared in Passapera’s memory six months later.

“It was really a mess,” she recalled. The teachers, the principal and the parents slowly began to rebuild what once

was a vibrant turquoise building with tall greenery that decorated every nook of the campus that is so much a part of Cidra, known on the island as the City of Eternal Spring.

Week after week, parents and others in the community joined in the effort. As soon as the roads were safer to

Aydali Campa | Cronkite Borderlands Project

English teacher Melba Passapera, left, instructs her students at the specialized bilingual school Luis Munoz Iglesias in Cidra, Puerto Rico. She contacted a professor at Arizona State University to help get supplies for the school.

Puerto Rico : Restless and Resilient 20

Photo by Johanna Huckeba

navigate, parents such as Santos helped clear the disaster. They used chainsaws to cut through collapsed trees, cleaned classrooms and installed six water tanks to ensure the children had potable water. With their help, the school is nearly restored.

Hernandez, the principal, said she wasn’t surprised at the staff and community effort. She said the school is one in which “all the community is involved in the process of maintenance,” a school-community partnership that dates to 1999. Every month, members of the community clean, cut grass or paint to keep the school in top shape, she said. So it was natural for the community to come together to rebuild the school after the hurricane.

“We had to do it by ourselves with the help of the students, parents, teachers,” Hernandez said. “We had to do it because we wanted to start.”

But Hernandez’s pride in the community effort was tempered by the loss of her father.

“Due to the lack of electricity, he couldn’t breathe, and I lost him it,” Hernandez said.

Her father needed medical care that required electrical power to treat his asthma and pulmonary emphysema. Like millions on the island, her home lost electricity. The generator that powered her father’s nebulizer broke, and he died shortly before the repairman arrived.

“But the rest of the things I was lucky because my house doesn’t suffer that much,” she said, wiping her tears.

She found support and comfort from the tight-knit school community, and she said she admires her teachers’ efforts in helping students cope with their individual struggles after Maria.

School success at Luis Munoz Iglesias

K-12 is welcome in Puerto Rico’s educational system that was suffering budgetary problems and steep drops in enrollment even before the hurricane. In April, the Puerto Rico Department of Education announced the closure of 283 public schools following an exodus of about 40,000 students to the U.S. mainland since May of last year.

While Puerto Rico’s Secretary of Education Julia Keleher has faced harsh criticism for the closures, she believes it necessary to alleviate the financial crisis the island has been facing for years now, especially amidst its recovery from Hurricane Maria.

“Our children deserve the best education we are capable of giving them taking into account the fiscal reality of Puerto Rico,” Keleher said in a statement issued in Spanish in April. “Therefore, we are working hard to develop a budget that will allow us to focus resources on student needs and improve the quality of teaching.”

The school closures were announced a week after Gov. Ricardo Rosello signed into law the implementation of private school vouchers and “allegiance schools,” similar to charter schools on the U.S. mainland. The new program drew criticism from the teachers’ union.

“The educational reform that is being presented at this moment does not redound to the interests of Puerto Rican public education,” Aida Diaz, president of the Puerto Rico Teachers Association, said

in March.

The sweeping public-school changes come at a difficult time, as students and faculty are still recovering from the hurricane, Diaz said.

Passapera, for example, just re-acquired electricity at her home in April, seven months after the hurricane. By the end of April, 53,000 households still did not have electricity, making Hurricane Maria the cause of the second-

longest blackout in world history and the longest in U.S. history, according to economic research firm Rhodium Group. Many students, including graduating seniors such as Omaris Rosario Luquis, 17, still do not have electricity in their homes as they prepare to transition into college. They missed out on two months of college preparation.

Still, she considers herself one of the “blessed” ones in her school. Her home

Principal Debra Angie Hernandez said the community is heavily involved in maintaining the school in Cidra, Puerto Rico. Photo by Johanna Huckeba

“We are teachers who go the extra mile.”

21 Puerto Rico : Restless and Resilient

— Melba Passapera, teacher at Luis Munoz Iglesias in Cidra, Puerto Rico

Mi nombre es Diomarys García Cardona, tengo 16 años, y estoy en un décimo grado.

Le hice una carta a Puerto Rico, y dice así; Mi Puerto Rico, Son tantas cosas que quiero decirte. pero no es suficiente papel en el mundo para plasmar lo mucho que significas para mí. No hay suficientes manos para escribir lo bondadoso y especial que es cada puertorriqueño.

No hay palabras suficientes en el universo que puedan describir con lujo de detalle lo ingenioso, creativo, trabajador, y luchador que es el boricua.

¿Sabes qué? Para mí, Puerto Rico no se levanta porque nunca se cayó. Puerto Rico no es la energía eléctrica inexistente, ni la falta de agua ni el techo que se llevó María.

Puerto Rico es aquel vecino que te dio agua cuando no tenías, el que te pasó una extensión para conectar la nevera.

Son todos aquellos vecinos que ahora después del paso del huracán María, salieron de su casa con pico, pala, y machete en mano para abrir camino y poder visitar a sus seres amados.

Mi Puerto Rico es la sonrisa deslumbrante de aquel niño que María le llevó a su hogar, pero no la pureza y el valor.

Esa sonrisa bella, deslumbrante y de dientes de leche, es suficiente para alumbrar el universo entero si esto estuviera oscuras.

Te amo Puerto Rico, con todo mi ser.

‘Dear Puerto Rico’

“Dear Puerto Rico” was a writing assignment that bilingual instructor Melba Passapera gave to her Cidra elementary school students in the wake of the hurricane. Her former student Diomarys Garcia Cardona joined in with an ode to her homeland.

Hi, my name is Diomarys Garcia Cardona, I am 16 years old, and I am in 10th grade.

I wrote a letter to Puerto Rico, and it goes like this; My Puerto Rico, There are so many things I want to tell you, but there is not enough paper in the world to capture how much you mean to me. There arenʻt enough hands to write how kind and special each Puerto Rican is.

There are not enough words in the universe that could describe with enough detail how ingenious, creative, hardworking and tough Puerto Ricans are.

You know what? For me, Puerto Rico doesnʻt have to rise because it never fell down.

Puerto Rico is not its lack or electricity, lack of water or the roof that Maria took.

Puerto Rico is the neighbor that gave you water when you had none, the one who passed you a cord to plug in your refrigerator.

Itʻs all those neighbors that within hours of the passing of Hurricane Maria, left their houses with picks, shovels and machetes in hand to clear the way to visit their loved ones.

My Puerto Rico is the beautiful smile of the child whose home was taken by Maria, but not their purity or courage. That beautiful smile, with white and dazzling teeth, is enough to illuminate the entire universe if it were in darkness.

I love you Puerto Rico, with all that I am.

escaped severe damage. “Gracias al Senor” – thanks to the Lord – she said.

Some students were not as fortunate.

Kenneth González Cruz, 13, lost his home. His school uniform was one of the few belongings his mother could salvage before the hurricane demolished the house.

Eight students and one teacher lost their homes to the Category 4 hurricane.

Passapera’s own experience as well as the ordeals that her students and Principal Hernandez experienced sparked a desire in her to go beyond physically repairing the school.

“So we were thinking our problem was, ‘Where are these kids going to do their homework?’” Passapera said. “‘Where are they going to for their free hours?’”

That is when Puertas Abiertas – “open doors” – started to take shape.

Passapera was inspired by a piece written by an Arizona State University communications professor Manuel Aviles-Santiago for Puerto Rico’s largest newspaper, El Nuevo Día. In it, he described how immediately after the hurricane, he started teaching his class in the dark in solidarity with the crisis Puerto Ricans were facing. She admired his initiative.

“We didn’t know how long we were going to be in the dark, and education is the only way that I thought at that point we’re going to be able to just start over again,” Passapera said.

With the help of her family, which was in Arizona at the time, she contacted Aviles-Santiago and explained her idea of Puertas Abiertas in hopes that he would help make her vision a reality.

She pitched the idea to Hernandez, who provided a large storage room in the upstairs corner of the building.

Passapera bought paint as soon as the local paint store reopened in November.

Puerto

: Restless and

22

Diomarys Garcia Cardona. Video by Johanna Huckaba

Rico

Resilient

Teacher Elymary Dones and parents jumped into the development, too. Santos said she couldn’t pass on the opportunity to help create something that would allow her daughter Marina Loraine to cope with her emotions after Maria.

“For me, school is my children’s second home,” Santos said.

Her family was involved in every step of the recovery, as well as the creation of Puertas Abiertas.

In January, the school received a dozen boxes full of school supplies, including backpacks, books and even board games following Aviles-Santiago outreach in Arizona and other states.

Parents and even students built the program through small monetary donations and physical labor.

By February, Puertas Abiertas was up and running.

Before she created the program, Passapera made do with the limited

resources available when the school reopened in mid-November, holding class outside and teaching arts and crafts with debris from the hurricane such as small branches that were scattered around the campus.

Now, her idea, Puertas Abiertas, is an integral part of the school’s curriculum at every grade level.

Hernandez describes the program as an “emotional shelter” because students can forget about their personal struggles while engaging in a safe space.

Students at every grade level visit the former storage room and engage in activities ranging from yoga and readings to arts and crafts and reflective writing.

Jacque Marlin, a life and wellness coach, often visits the space as a guest speaker.

In March, Marlin lead Passapera’s fourth-grade class in meditation at Puertas Abiertas. She then recited from her

book, a work in progress about how to emotionally “tame the dragon” that was Hurricane Maria.

“She could not control the storm, but she could control how she reacts,” Marlin read.

Passapera said she has seen improvement in her students’ ability to focus and work independently since she started implementing creative and physical activities for the students.

Teachers constantly asked each student since their first day back if they had water, electricity and shelter, she said.

“I don’t feel nervous anymore,” said student Marina Loraine Santos, who was shaken by the impact the hurricane had on her home.

Other students attribute their academic and emotional recovery to simply the school’s outreach.

“The teachers who’ve been in my life have worried about my personal life, my

personal growth,” said Rosario, a 12thgrade student who’s been attending the school since kindergarten.

Passapera felt a program such as Puertas Abiertas was essential to show her students that they were not alone in their recoveries from Hurricane Maria. The faculty understood the emotional toll of the natural disaster, as they faced the same ordeals their students faced.

“We are teachers who go the extra mile,” said Passapera, who earns $31,000 annually, about $7,000 below the average beginning salary for teachers on the mainland United States.

She has 24 years of teaching experience, two bachelor’s degrees, a master’s degree and a bilingual teaching certification.

Her goal is for students to learn to be productive members of their community and their nation, especially in times of need, more lessons driven home by Hurricane Maria.

English teacher Melba Passapera’s desk has drawings made by her students at the Luis Munoz Iglesias school in Cidra, Puerto Rico.

Photo by Aydali Campa

Students at specialized bilingual school Luis Munoz Iglesias in Cidra, Puerto Rico, share words to describe their experience of Hurricane Maria as part of a “Puertas Abiertas” (Open Doors) lesson. Photo by Johanna Huckeba

23 Puerto Rico : Restless and Resilient

Path to Recovery

CAROLINA, Puerto Rico –

The school bell rings to end the day’s activities at the very busy campus of Dr. Modesto Rivera, Rivera Elementary School, yet, for principal, Migdalia Nieves, the day is far from over.

As she waves goodbye to her students heading through the school’s front gates, she quickly

returns to her office to continue her work, checking on the progress of her students after missing weeks of school due to Hurricane Maria.

When Maria plowed through Puerto Rico back on Sept. 20, 2017, schools all over the island braced for the impact this storm would have on their buildings, faculty and students.

However, they did not imagine the magnitude of challenges they would face to get their schools reopened, staffed, and classrooms fi lled with returning students.

In the days leading up to the disaster, schools all over the island prepped for the arrival and inevitable destruction that was to come with nothing to stop it.

In the months to follow, two schools would face numerous challenges as they worked to get their students moving past the difficult consequences of Maria.

Story and photos by Cariño Dominguez | Cronkite Borderlands Project

Story and photos by Cariño Dominguez | Cronkite Borderlands Project

Puerto Rico : Restless and Resilient 24

Parents of school children and community volunteers have worked to help open schools across the island in the wake of Hurricane Maria.

Dr. Modesto Rivera Rivera

Carolina, Puerto Rico — Dr. Modesto Rivera Rivera is an elementary school in the small town of Carolina, Puerto Rico. Painted yellow and trimmed in turquoise, in the typical fashion of schools found all over the island, yet under the roof of this school organized chaos best describes the scene.

Six months after the hurricane, Principal Migdalia Nieves, does what she can to help get her school and her students back on track.

She has faced a very difficult situation where after a month upon returning to her school, Maria Esposito Elementary School, The Puerto Rican Department of Education chose to close her school down, forcing her to leave and take up the directorship of Modesto.

“This school didn’t suffer,” Nieves said pointing down to her desk in her office at Modesto. “My school suffered. I mean the

one I came from suffered, because it was a poor neighborhood,” Nieves said.

Although exact numbers are still unclear, according to a recent report, it is estimated that 1 in 11 students (about 26,000) have left Puerto Rico for the United States.

With the ongoing debt crisis in the U.S. territory, at the end of the 2017 school year last May, the Department of Education was forced to close 167 schools.

They will now close even more.

Maria Esposito Elementary School is where Nieves was directing before coming to Modesto.

Her change to Modesto was sudden and abrupt.

Nieves faced a dilemma that many schools around Puerto Rico had to deal with; leaving their own school to consolidate with another after the effects of Maria. In her case, the damage to the school building and the loss of many

students who left the island forced her to move into the current building she currently directs.

The transition is what proved the most difficult during this time. “Look, I’m going to be very sincere,” Nieves said with determination in her face. “It could have been better.”

“If there had been good communication, in many aspects, it could have been better. Making such a sudden change, there wasn’t the time to discuss it.”

Nieves was given a few days’ notice that she would be forced to leave her school. She was still dealing with the rumors that many of her students, up to 50 had left the island altogether. Conflicting information poured in about her own staff. In the end, 30 teachers did not return.

Zilka Figueroa was teaching at Esposito before following Nieves to Modesto. “My room is in a closet,” she explains as she struggles to open the door to her music

Left: The Dr. Modesto Rivera Rivera in Carolina is rebuilding because of Hurricane Maria. It has a new principal and a student body that has been consolidated due to the exodus of students to the mainland U.S. and the educational system’s financial challenges.

room.

Figueroa teaches general music and recorders to the fourth and fifth graders of Modesto.

“We are in the music room for the hand bells,” Figueroa says as she looks around the tiny room. “The regular music classes I give in their own rooms and they stay in their room and I go over there.”

Indeed, the room is small. Dim, from the half-way closed shutters with books and materials strewn across a long table set off to the side and hand bells laid out over another attached to it.

When the closing of Esposito was announced, there was never any doubt that Figueroa would join Nieves as she transitioned to Modesto. Figueroa recalls the difficult transition period.

“Maria Esposito was closed for two months,” said Figueroa. “First the hurricane hit, then we needed to wait for the department to give us permission to

“I am hopeful because we could have been worse off. However, we’re still here and we’re fine.” – Migdalia Nieves, principal of Dr. Modesto Rivera Rivera Elementary School

25 Puerto Rico : Restless and Resilient

start. One month after school started again, they told us they were closing Esposito and moving us to join another school.”

As challenge after challenge began to pile on each other, the most difficult task proved getting their students back on track. They were months behind and slipped further away from the standard of excellence Nieves was accustomed to.

“Before the hurricane, well at least at the school that I come from, we achieved academic excellence,” Nieves said. “Sadly, we just achieved it this year, and now that my school is closed, that’s what I want again … excellence.”

“I want to take the children to their maximum potential,” Nieves continues. “So they can be productive children. I don’t want to just see them trying to be rescued from so many problems in the streets, but to see something positive.”

Nieves is hopeful about her future, the future of the students and of her school.

“Well look, I’ve seen that they have a great desire to continue,” Nieves said, reflecting on her students.

“Yes, they have been affected, because there are many of them who don’t have a home. Many of them lost their roof, or even their fathers who left the island.”

The Puerto Rican Department of

Education is allocating funding for each school, however in situations like Modesto, there simply is not enough to go around.

“They are working on it now because, the Departamento isn’t clear which school we are,” Figueroa said. “Is it Modesto, or Maria Esposito? Maria Esposito is now closed so they think they just need the funding for the Modesto kids, but they are not counting that we have two schools here.”

With hundreds of schools vying for assistance from the Department of Educations, Modesto does what it can to get their voices heard among the crowd of many.

“It’s challenging,” Figueroa continues, “So, we have to always explain, hey, we have two schools here, so we need maybe more food for the kids for lunch or maybe more books or chairs for them.”

The situation they fi nd themselves in adds to the stress of accommodating so many students in such a small space. It takes a toll on everyone.

“We are very sentimental right now, the kids and the teachers. We have to work with the emotional part because everything makes us cry. The loss. It’s very hard for us making the change.”

Nieves recognizes that the lost months

of steady school work has set her students back considerably. The best she can do is help support them and their families as they struggle outside of the school as well.

“The support I give them, here at least, I’m always positive in helping. Parents are always there telling their stories and I never close that door to any parent. I don’t give appointments either. If they need me in that moment, I give it to them in that moment. Because I don’t know how things will be tomorrow, so I give it to them now because they need me now.”

“I am hopeful,” Nieves continues, “because we could have been worse off. However, we’re still here, and we’re fi ne.”

As Modesto struggles, the school year continues with or without them. They won’t know the implications for lost time until they can evaluate the situation towards the end of the school year.

However, a new threat to their school lies before them.

Recently, education officials announced that another 283 schools will be closing due to the massive exodus of students to the mainland and the continuing fi nancial issues.

“We remain optimistic,” Nieves concludes. “Giving strength to those who don’t have any. Of course, there is hope. I believe it, that Puerto Rico does get back up.”

Papa Juan 23 Superior High School BAYAMON, Puerto Rico – At Papa

Juan 23 Superior High School, the campus is bustling with life and noise. Groups of students run along the walkways of the school, laughing and complaining about their homework. The typical sounds of a high school you may fi nd anywhere and yet not typical for a school that survived Hurricane Maria six months prior.

Papa Juan is a success story yearning to be told.

Within three weeks of Hurricane Maria’s destructive landfall on Puerto Rico, Papa Juan opened its doors to excited students, eager to return to their favorite teacher’s classrooms and to their friends whose parents decided to remain.

Principal Ivelesse Negron-Soto has directed Papa Juan for five years. In total, she has dedicated 25 years to educating the children of Puerto Rico.

Negron-Soto, 55, and former special education teacher for deaf children, signs with her hands as she speaks about her many years working with the children of her homeland.

“Soy muy feliz, I am very happy in my work,” Negron-Soto said. “Because any problems that come my way, I have a solution for.”

On Sept. 20, 2017, Hurricane Maria came her way.

“Maria was a different category,” Negron-Soto describes. “Category 5, a category that did not exist, and the destruction was quite strong.”

“Two days after the hurricane, I show up here at school and the counselor arrived and we entered together.”

The experience was an emotional one for both of them. Negron-Soto had made Papa Juan her home and the students were her family. She wondered how they would recover.

Far left:Principal Migdalia Nieves of Dr. Modesto Rivera Rivera Elementary School.

Puerto Rico : Restless and Resilient 26

Left: Zilka Figueroa teaches general music and 4th and 5th grade recorders.

“Honestly, the trees here made the entrance completely obstructed. Then the teachers showed up at the school because they have a lot of feeling of belonging.”

In the days to follow, the teachers, administration and students took it upon themselves to gather together every day for three weeks to clear the debris and clean the school.

“It really was a team effort that could not have been done without them. Here the teachers brought the shutters, power plant and materials we needed, and we didn’t wait for FEMA to clean our school, no, we did the work ourselves.”

With still no power but debris cleared, and the school cleaned, they were ready to open their doors to their students and faculty, but they still had to wait approval from the Department of Education.

Alondra Sarrano is a junior at Papa Juan. After Maria hit, hers was one of the hundreds of families contemplating leaving the island. Alondra’s parents are divorced, and her mother had made the choice to leave Puerto Rico for work in the United States.

Determined to practice her English, Alondra describes what she felt at the thought of leaving Puerto Rico.

“It was horrible even me thinking I was

going out. It was heartbreaking leaving all my family here and maybe not seeing them for like a year with all my activities and celebrations not being with them.” She continues, “When I told my sisters they cried so much, it was horrible!”

Sarrano ended up staying in Bayamon. According to her description of the situation, she received a “technicality” and there were issues with her visa that prevented her from going.

Rafael Perez is a senior at Papa Juan and like many others, his family faced a tough decision whether to stay or go. Perez’s father has a heart condition and with the stress of the hurricane the family thought it would be best to send him to their other son in the United States.

“We stayed like family,” said Perez. “We helped each other.”

“Altogether, we only had seven students leave Puerto Rico,” Negron-Soto said, “But four have already returned to school here.”

Papa Juan did not see a mass exodus of their students after Maria as many other schools around the island did. They were never forced to close or to consolidate with another school.

Negron-Soto contributes the strength of their school to remaining united and intact

during the difficult times.

Among the entire faculty of Papa Juan, only one teacher, the 11th grade English teacher left for Florida to fi nd work. A favorite among the students, this teacher eventually did return to Papa Juan to the pride of Negron-Soto.

Academically, Papa Juan is striving to get the students caught up. Returning to school just three weeks after the hurricane hit was a huge advantage the students had over others whose return did not happen for months. “Academic obstacles from Maria were students falling behind, but the teachers are working hard.”

According to Negron-Soto, “PBL, or project-based learning was implemented.”

Project-based learning is a studentcentered program that helps prepare students for academic, personal and career success. It involves a dynamic classroom approach that is believed to help students be ready to face real-world challenges. PBL also teaches by prompting students to be inquisitive asking and answering questions to help problem solve.

“PLB helped a lot,” said Negron-Soto. “We hope for the academic fulfi llment of the students and I understand we are quite up to date.”

The student body is longing for the internet to be reinstated as soon as possible.

“Our books are outdated, and we really need more current information to help supplement what our books are lacking,” said Negron-Soto.

“Hurricane Maria did have an impact,” Negron-Soto said. “It impacted the students socially and emotionally and the employees and all of us, but I believe that the key has been that we have supported one another. We have been helping each other and the teachers have helped the students.”

“We have to work for the best good of the student - our reason for being,” she said. “Without students, we do not have a reason to be in school.”

The Future

The education system in Puerto Rico has faced many challenges in its years of schooling its island’s children. However, with the many proposed changes coming its way, including an unprecedented 283 schools scheduled to close after the 2018 school year, only time will tell who truly survived the destructive impact of Hurricane Maria.

Far left: Principal Ivelesse Negron-Soto said the Papa San Juan school community has stayed united during the ordeal.

Left: Senior Rafael Perez said his family contemplated moving to the mainland to seek care for his father’s heart condition but stayed.

“We stayed like family. We helped each other.”

27 Puerto Rico : Restless and Resilient

— Rafael

Perez, senior, Papa Juan 23 Superior High School

CIALES, Puerto Rico

– The night Hurricane Maria ravaged the island last September, Martha Rivera worried most about her daughter, Melissa.

More than seven months after the hurricane, she finally is able to sleep at night. Two weeks ago, power was restored to the family home, but with spontaneous power outages throughout the island, Melissa’s well-being is at risk.

Rivera had worried for more than half the year that the two generators keeping her 23-yearold daughter alive would fail and Melissa would die. Melissa is bedridden, diagnosed with cerebral palsy and multiple maladies that have left her deaf, partially blind and unable to speak.

“Having power back is still surreal to me, I thank God for it every second,” Rivera said through an interpreter by telephone. “I pray that the families who are still in the darkness will get power back soon. For this I pray every day.”

The cords that keep Melissa alive are strung around the foot of her bed. The feeding tube through which her mother delivers her meals each day – a variation of chicken or turkey

flavored baby food mixed with water and Enfamil – hangs with a collection of translucent tubes that run from different parts of Melissa’s body connecting her to the machines she needs to breathe. Her vital medical equipment includes a reclining motorized bed, an asthmatic nebulizer and a medical suction device used to prevent her from choking on food or liquid.

“It is a miracle that they finally got power back,” said Dr. Sally Priester, who has voluntarily assisted the family since the hurricane. “Melissa requires 24/7 care, and so for Martha to have one less thing to worry about means everything. It means there is hope for Melissa.”

The family home sits at the top of a muddy, winding road in small community located within the island’s central mountain region. When Cronkite News reporters visited the home in early March, it had no power and only a partial roof. Rivera, who painstakingly cares for her daughter, was distraught.

“My biggest fear is that I stay sleeping and when I wake up, she is not breathing anymore,” Martha Rivera said in Spanish. “That is why I don’t sleep. I don’t sleep because that brings me fear;

Olivia Richard and Lerman Montoya | Cronkite Borderlands Project

Puerto Rico : Restless and Resilient 28

Melissa Rios Rivera (top and right), 23, lives in Ciales, Puerto Rico, with her mother Martha Rivera (above) and her father Jose Manuel Rios. She is bed-bound due to her cerebral palsy, which impacts her movement, muscle tone and posture. Her life depends on the machines that are operated by electricity, like her electric hospital bed, fluid suction, and her asthmatic nebulizer. Photos by Lerman Montoya

29 Puerto Rico : Restless and Resilient

Two gas-powered generators were what kept Melissa alive during the seven months her home was without power. Photos by Olivia Richard

that I get up and see she’s not breathing.”

Families across Puerto Rico have had to cope with long periods without electricity since Hurricane Maria devastated the island Sept. 20, 2017. Just 14 days before Hurricane Maria made landfall, Hurricane Irma had left nearly 1 million residents without power, according to global humanitarian aid agencies.

An estimated 50,000 Puerto Ricans remain without power, many of them in rural and mountainous regions such as Ciales. Many families depend on gasolinepowered generators to power their homes. The hum of generators was heard throughout the lush forests in the center of the island during Cronkite’s March visit to the island.

The Rios-Rivera family used two generators to keep Melissa’s equipment running. Jose Manuel Rios, Martha’s husband, works as a landscaper in the towns surrounding Ciales and most nights does not return until 9. He worked 12hour days to pay for gasoline to fuel the generators, leaving only the $700 the

family receives monthly through Social Security for other expenses.

One generator, lent to the family by a nephew who left the island for the mainland after the storm, was used to cool Melissa’s room, which must be kept at 66 degrees 24/7 to prevent her from going into convulsions. The second generator, which was 14 years old and in need of repair, powered all the other devices Melissa relies on. The rest of the house was dark.

The devastation of the hurricane posed yet another challenge for a family that has already seen many trials, especially in caring for Melissa.

The couple had struggled to conceive before Melissa was born. As a baby, Melissa shook uncontrollably. Her parents didn’t realize at the time she was having seizures.

Frantic, Rivera took her daughter to the hospital, where doctors diagnosed Melissa with cerebral palsy, which impacts her motor skills, muscle tone and posture.

“I constantly have to be over her if she coughs, if she spits; if she starts choking she turns blue because for lack of oxygen. She depends on her machines and the air conditioner.” — Martha Rivera

They also diagnosed her with asthma, severe scoliosis and several other disorders that rendered her blind and deaf in her left ear.

Melissa has never taken her fi rst steps, and she can’t feed herself. She communicates with her mother through a series of blinks and eye rolls. When she chokes, Rivera suctions the saliva and mucus from her throat.

“I constantly have to be over her if she coughs, if she spits; if she starts choking she turns blue because for lack of oxygen,” Rivera said. “She depends on her machines

and the air-conditioner.”

But the hurricane and its aftermath only strengthened the bond between mother and daughter.

“I know that when God sent me Melissa, it was a proposal,” Rivera said. “Not everyone in the world is sent this. And she, how she is, is still my daughter. I love her, I adore her, and if I have to give her my last drop of blood, I will.”

Puerto Rico : Restless and Resilient 30

Puerto Rico’s rural mountain towns and municipalities were some of the last to receive aid after Hurricane Maria because of their remote location and the island’s relatively poor roads. Many of the people in these areas are residents who have chosen to stay on the island rather than migrate to the mainland United States. Due to lack of resources, they are some of Puerto Rico’s most vulnerable people — but they are also among the most resourceful and resilient.

Yauco, Puerto Rico

Yauco is a large municipality located in the southwest of Puerto Rico. Yauco starts in the central mountain range of the island and rolls down into a valley extending to the Caribbean Sea. Known as “El Pueblo de Cafe” (Coffee City), Yauco is the main producer of coffee on the island.

In 1899, Hurricane San Ciriaco, a Category 4 hurricane, tore through the island’s coffee plantations and devastated the coffee production, with damages totalling approximately $10 million.

Hurricane Maria did the same, leaving coffee farmers throughout Yauco with little to no hope of rebuilding their industry. Photos by Lerman Montoya

31 Puerto Rico : Restless and Resilient

Yauco

Yauco, Puerto Rico

Manuel Dox is the owner of Hacienda Mireia, a coffee farm in the high mountains of Yauco. Dox’s grandfather awas a coffee farmer and inspired Dox to leave his finance job in New York City and pursue coffee farming. After Hurricane Irma and Hurricane Maria ravaged the island, Dox’s 50 acre coffee plantation was completely destroyed, leaving him and his wife scrambling to make ends meet.

Dox named his coffee plantation after his wife Mireia Casamitjana, who he met while they were studying in Babson College in Massachusetts. After he expressed his passion for starting a coffee plantation, Mireia left her pharmaceutical job in Barcelona and joined Dox.

“A man and his wife can only do so much,” said Dox after explaining how they are slowly running out of money to invest in the coffee plantation. “From making six figures in New York City to barely making anything ... We are living off of savings and Puerto Rican farmers insurance. To rebuild what we used to have and make this plantation productive, it takes much more than what we receive.”

32

Puerto Rico : Restless and Resilient

Yauco, Puerto Rico

Since the hurricane, Dox and his workers were able to re-plant 1,500 coffee plants. They started a coffee plant nursery with the coffee beans they salvaged from the hurricane. Dox said that the Puerto Rican government is responsible for providing coffee farmers with plants to help sustain their farms, but the process has been problematic since the hurricane.

33 Puerto Rico : Restless and Resilient

“This is our little experiment,” said Dox.

Adjuntas, Puerto Rico

Adjuntas is located in the central mountain range of Puerto Rico. Known by islanders as “La Ciudad del Gigante Dormido,” (The City of the Sleeping Giant), Adjuntas sits atop some of Puerto Rico’s tallest mountains.

Half of the population falls below the average median income, making Adjuntas one of the poorest mountain towns in Puerto Rico.

Hurricane Maria left over 18,000 people without electricity for over six months.

Adjuntas

Photos by Lerman Montoya

34

Puerto Rico : Restless and Resilient

Adjuntas, Puerto Rico

The night that Hurricane Maria made landfall, Olga Pagan Alicea, 63, sought safety in her daughter’s home. The winds battered the walls. Water began pouring in through the windows and roof.

When the sun came up, Pagan Alicea still hadn’t gone to sleep. Through the living room window, she could see her roofless house in the distance.

“When I saw the second floor of my home completely blown off by the winds of the hurricane, I couldn’t do anything else but cry,” Pagan Alicea said.

35 Puerto Rico : Restless and Resilient

Adjuntas, Puerto Rico

The name Maria has changed the way Pablo J. Sanabria, 94, feels. Since his birth in 1924, he has never experienced a more difficult hurricane. “Talking about this hurricane gives me goosebumps. I have nightmares every night.” Hurricane Maria left Sanabria without electricity for over five months. He is the owner of La Casa de Postales, a postcard business that has been operating since the 1950s. The doors to his business are once again wide open and he now has electricity.

Puerto Rico : Restless and Resilient 36

Adjuntas, Puerto Rico

After Hurricane Maria struck the island, Carmen Roman, 85, was left without electricity and access to food, roads, and clean water. She lives miles from the city center but travels down the mountains of Adjuntas by foot to visit friends and family a few times a week. She is known to some in the town as the “Mountain Lady.”

37 Puerto Rico : Restless and Resilient

Ponce, Puerto Rico

Ponce is the second largest city/municipality in Puerto Rico following San Juan. Known as “La Perla del Sur,” (The Pearl of the South), Ponce’s northern boundary begins in a mountainous region that flows into a valley and reaches the island’s southern coast.

After Hurricane Maria made landfall, Ponce’s population of almost 200,000 lost electricity and easy access to food and water. Though much of Ponce’s coastline and city center regained power relatively quickly, farmers in the mountain regions remained without power for months.

Ponce

Ponce, Puerto Rico

Only 1,500 of the over 7,000 coffee plants remained on Hacienda Pomarrosa after Hurricane Maria.

Photos by Lerman Montoya

Photos by Lerman Montoya

Puerto Rico : Restless and Resilient 38

Ponce, Puerto Rico

Kurt Legner, owner of Hacienda Pomarrosa, a coffee plantation in the mountains of Ponce, has dedicated his life to the coffee industry. He and his wife and co-owner of the hacienda, Eva Lisa Santiago, knew that starting and owning a business would be hard, but they were not prepared for the destruction of Hurricane Maria.

Legner and Santiago offer tours, coffee tastings and bed and breakfast lodging on their hacienda but since Hurricane Maria, tourism to the central parts of the island has been scarce.

39 Puerto Rico : Restless and Resilient

“It has been very hard since the hurricane. We have not had as many people come to tour,” said Legner. “But we are hopeful this will change.”

Ponce, Puerto Rico

Hurricane Maria did not crush Eva Lisa Santiago’s spirit. She said she has poured her entire life’s savings into the business and will do everything she can to see her coffee plantation, Hacienda Pomarrosa, grow.

Ponce, Puerto Rico

Hacienda Pomarrosa still produces coffee, but at a much smaller scale. Though thousands of coffee plants were lost because of the hurricane, Santiago is determined to serve all her guests cappuccinos or expressos.

Puerto Rico : Restless and Resilient 40

The demand for their coffee is high, but because of the hurricane they have been selling their coffee beans online.

41 Puerto Rico : Restless and Resilient

Ciales, Puerto Rico

The Roja family members have lived in Ciales their entire lives. Hurricane Maria destroyed the family’s home. They found refuge in a home that was lent to them by a neighbor who lives in the mainland United States. The temporary home also suffered severe damage. A blue FEMA tarp serves as a roof for parts of the home.

Seven-year-old Julio is the youngest of the Roja family. The night Hurricane Maria hit the mountain town of Ciales, he did not sleep. His sister, Angeles, who is 8, watched over Julio as he cried throughout the night.

Ciales, Puerto Rico

Known by islanders as “Los Valerosos” (The Valiant Ones), Ciales is located in the central mountain range of Puerto Rico.

Half of the population falls below the average median income, making Ciales one of Puerto Rico’s poorest mountain towns.

Hurricane Maria ravaged Ciales, leaving over 19,000 people incapable of accessing roads and without light for over six months. Ciales is only 45 minutes away from San Juan, but many residents did not see FEMA agents until a month after Hurricane Maria made landfall.

Ciales

Photos by Lerman Montoya

Puerto Rico : Restless and Resilient 42

Ciales, Puerto Rico

There are seven children in the Roja family: Kaxushaka, 12, Francheska, 17, Benjamin, 8, Angeles, 8, Julio, 7, Mariela, 12, and Joselyn, 15. Their mother is not in their lives after a custody dispute with their father. Their father works to provide for them and in the home, the oldest sisters, Francheska and Joselyn, play the mother’s role.

43 Puerto Rico : Restless and Resilient

Patillas, Puerto Rico