27 minute read

The sky's not the limit, it's just the beginning in Dayton, Ohio

Story and Photos by Kris Grant

You may not have thought of Dayton, Ohio as a travel destination, but I think it’s well worth your consideration. You could easily spend five days here exploring this city of countless innovations.

There was the airplane, of course, and the legacy of its native sons, Wilbur and Orville Wright led the city to become a center for aviation. Exploring Dayton’s many aviation sites and museums will start you down a road of discovery of Dayton’s many “firsts.”

Beginning in the mid-1800s, Dayton established itself as a center of manufacturing and entrepreneurship. Its rise as a city of industry and innovation in the 19th and early 20th centuries was fueled by a combination of natural geography, transportation infrastructure and entrepreneurial energy.

The Miami and Erie Canal opened in Dayton in 1829. The canal was crucial, connecting the Ohio River and Cincinnati to Lake Erie at Toledo, making Dayton a central port on a 274-mile inland waterway. It allowed cheap and efficient movement of raw materials and goods, giving Dayton manufacturers access to national markets. The canal also powered water wheels and millworks, providing energy for early factories – a huge advantage before the widespread use of electricity. Railroads arrived in the 1850s and Dayton quickly became a major rail junction. Dayton also sits on flat planes ideal for building mills, factories and homes. Its downtown street layout –

compact and walkable – encouraged clustering of small manufacturers, which fostered cross-pollination of ideas and skills.

Dayton’s collective penchant for building better mousetraps led to a myriad of marvels that made life easier in the 20th century such as automobile ignition switches, the cash register, freon that revolutionized refrigeration, the first pop-top cans, and price-tag affixing machines. The first telephone book directories were printed in Dayton, and bar codes were invented here.

Companies such as NCR, the Barney & Smith Car Company, McCall’s Publishing, Delco, the Wright Company, and the Huffy Corporation set Dayton apart in innovation and forward thinking.

It was the Silicon Valley of the early 20th century.

In addition to driving industrial success, Dayton’s business leaders helped shape the city’s cultural and physical landscape – contributions that remain sources of pride today.

So, prepare for takeoff – you’ll find plenty to love in Dayton.

The National Museum of the U.S. Air Force

I recommend this museum – the oldest and largest military aviation museum in the world – as your first stop. You might want to just visit part of the museum on your first day, perhaps visiting two of its hangar galleries, then returning for a second day to take in more, plus the National Aviation Hall of Fame.

Admission and parking are free, making repeat visits budget friendly.

The museum is housed at WrightPatterson Air Force Base, one of the largest military bases in the U.S., spanning over 8,000 acres and hosting an impressive 11,000 aircraft operations annually. With more than 30,000 military personnel, civilian employees, and contractors, it’s not just a hub for defense but for cutting-edge aviation research. The base is home to the Air Force Material Command, Air Force Research Laboratory, and the Air Force Institute of Technology, making it a powerhouse of innovation.

The museum’s four massive hangars span 19 acres and hold over 350 aircraft and missiles on display, tracing the evolution of power from the Wright brothers to today’s cutting-edge stealth technology.

Early Years Gallery

Here a highlight is a full-scale replica of the Wright Military Flyer – built in 1909 and purchased by the U.S. Army. Visitors can see early biplanes, dirigibles, and hot-air balloons that were developed in Europe and in many cases preceded the Wright Brothers attempt at flight. Aircraft like the Curtiss JN-4 “Jenny” and the SPAD XIII illustrate the transition from experimentation to militarization.

World War II Gallery

One of the museum’s most dramatic collections showcases the rapid expansion and innovation in aviation during the 1940s. Standouts include the Boeing B-17F Memphis Belle,

beautifully restored and displayed as it might have appeared on its 25th mission over Europe. A rare Messerschmitt ME 262, the first operational jet fighter, provides a glimpse into German technology, while the B-29 Superfortress Bockscar, which dropped the atomic bomb on Nagasaki, serves as a sobering reminder of war’s consequences. Exhibits also highlight the role of the Tuskegee Airmen and women pilots in the WASP program. Korean and Southeast Asia Gallery Here, jet propulsion comes into full focus with the F-86 Sabre and MIG-15, legendary adversaries in the Korean War, hanging side by side. The Vietnam War section includes the AC-130 Spectre gunship, F-4 Phantom II and a chillingly authentic Forward Air Control (FAC) display. A recreated POW cell honors those who endured captivity during the Vietnam era.

Cold War and Space Gallery

The Cold War Gallery may be the most visually striking, especially the re-created silos holding Minuteman missiles. The enormous B-36 Peacemaker dominates the hangar alongside the sleek SR-71 Blackbird, capable of speeds over Mach 3. The gallery explores the doctrine of mutually assured destruction, espionage and the growing role of unmanned systems. One of my favorite stops was the Presidential Aircraft Gallery, featuring historic planes used by presidents Roosevelt, Truman, Eisenhower, and Kennedy. You can walk aboard each plane, view the president’s private quarters, with early versions featuring fold-out beds. I’ve visited the Ronald Reagan Presidential Library & Museum, and his Air Force One on display there was more elaborate and impressive, with a separate bedroom. I imagine more recent Air Force Ones are even more luxurious. But it was eerie to be on the Kennedy plane, SAM 26000, particularly, knowing that this is the plane that flew JFK’S body back from Dallas and where LBJ was sworn into office, as young Jackie Kennedy, still wearing her pink suit, stood in the background. The floor layout was subsequently remodeled, but it was hard to imagine how all those people were crowded into that small swearing-in ceremony space.

Beyond these exhibits, the museum includes a memorial park, flight simulators (there is a fee involved here), a digital theatre, aircraft restoration hangars and rotating temporary exhibits.

Also within the museum is the National Aviation Hall of Fame. It’s a powerful and personal interactive gallery that humanizes the history of flight with tributes to the visionaries, pilots, engineers and astronauts whose achievements shaped the skies and space. Founded in 1962 and chartered by Congress in 1964, it preserves and honors the legacy of more than 250 enshrinees. They include pioneers like the Wright Brothers, Glenn Curtiss, Charles Lindbergh and Amelia Earhart; military heroes like Chuck Yeager and Jimmy Doolittle; astronauts including Neil Armstrong, John Glenn and Sally Ride, and industrialists like Henry Ford and Alexander Graham Bell who played a role in aviation.

Locals will recognize the names of Theodore “Spuds” Ellyson, the first naval aviator, U.S. Navy Vice Admiral James Bond Stockdale, recognized for

exhibiting discipline and moral courage during his 7 ½-year imprisonment in the “Hanoi Hilton,” and actor and World War II naval aviator Cliff Robertson, who co-founded the EAA’s Young Eagles program aimed at encouraging youth in aviation.

The Wright Museum and Carillon Park

Sprawling across 65 landscaped acres near the banks of the Great Miami River, Carillon Historical Park is both a museum and a beautifully curated time capsule of Dayton’s legacy of innovations. Operated by Dayton History, the park blends immersive exhibits, historic buildings and working demonstrations to tell the story of how this midwestern city helped shape the modern world.

At the heart of the park lies the Wright Brothers National Museum, home to one of the most significant aviation artifacts in the world: the 1905 Wright Flyer III. This was not just a prototype – it was the first practical airplane, capable of controlled, sustained flight. Orville Wright called it their most important aircraft, and it’s the only Wright airplane designated a National Historic Landmark.

Housed in the John W. Berry Sr. Wright Brothers Aviation Center, the plane is displayed in a soaring gallery that Orville himself helped plan before his death. Surrounding it are the Wrights’ original bicycle tools, glider models, wind tunnel replica and detailed narratives of how two quiet brothers from Dayton solved the riddle of flight through relentless experimentation.

After their successful first flight at Kitty Hawk, the Wrights needed a place closer to home to continue their flight experiments. They did so at Huffman Prairie, owned by a private friend and banker who allowed the Wrights to use without charge his flat, windswept 84-acre pasture located just outside Dayton. Here Wilbur and Orville Wright truly learned to fly, tested and refined the world’s first practical airplane, the aforementioned 1905 Wright Flyer III, and later trained the first military pilots.

Additional Carillon Park highlights include:

The Carillon Bell Tower The park’s iconic 151-foot tower features 57 bells and regular carillon concerts. It’s a visual and auditory centerpiece. It was a gift of Edith Walton Deeds, the wife of one of Dayton’s most prominent industrialists, Col. Edward Deeds. While traveling in Bruges, Belgium in the 1930s, Edith, an accomplished musician, was charmed by that city’s carillons and a seed was planted to one day share that music with Dayton.

Historic buildings Nearly 40 preserved structures include an 1815 tavern, a working 1930s print shop, a 1800s schoolhouse, and the original Deeds Barn, where Charles Kettering and his “Barn Gang” developed many of their famous inventions at a barn on his friend and fellow entrepreneur Edward Deeds’ estate.

Transportation Center See vintage trains, streetcars and a gleaming 1903 Barney & Smith parlor railcar.

The Carousel of Dayton Innovation This delightful, fully functional carousel highlights the city’s many inventors and industrial icons. Instead of typical horses, kids and adults can ride a cash register (honoring NCR), a parachute pack (from McCook Field development), a Wright Flyer and more.

At the Carillon Brewing Company, you can sample beer made using 1850’s brewing methods and recipies. Staff in period costumes brew beer in copper kettles heated by open flame. Dayton BBQ Company offers tasty food to pair with the beers.

The Carillon Park Rail & Steam Society’s miniature train (typically operates on weekends) is a one-eighth scale railroad that winds through part of the park and gives kids and adults a chance to ride a part of Dayton’s rail history.

A highlight of Carillon Park is the Heritage Center of Dayton Manufacturing and Entrepreneurship. This may have been my favorite park feature.

This modern exhibit hall features more than 300 significant inventions that came out of Dayton.

Interactive exhibits showcase Dayton’s contributions to the automobile industry, refrigeration, parachutes, powered flight and even space travel. From prototypes to patents the building captures the city of problem solving and practical creativity. It also highlights Dayton’s deep role in the early computer and defense industries.

Here are a few of the stories I discovered at the Heritage Center: During its Golden Age from 1915 through 1929, Dayton was known as “The City of a Thousand Factories.” In the early 20th century, the city became a technological powerhouse thanks to a remarkable cast of inventors and industrialists – chief among them Edward A. Deeds, Charles F. Kettering and John H. Patterson.

The National Cash Register Company (NCR) was a company founded by industrialist John Patterson in 1884, when he purchased for $6,500 an invention of James Ritty, a tavern owner. Ritty had invented the “Incorruptible Cashier,” a cash register designed to keep track of business transactions and discourage employee theft. Patterson was viewed as the pioneer of the modern work force, offering formal sales training, sales territories and a customer focus. He coupled that with progressive employee policies and a sense of social responsibility.

Fast forward 20 years to 1904 when Dayton native Edward Deeds oversaw factory operations at NCR. Deeds was a visionary engineer and businessman whose talent for organizing teams helped create Dayton’s innovative ecosystem.

Deeds was deeply interested in improving technology, and needed someone to help electrify NCR’s cash registers, which were still mechanically operated. He heard about a bright young engineer working at the Star Telephone Company in nearby Ashland, Ohio –Charles Kettering, who had recently earned an electrical engineering degree from Ohio State University. Deeds hired Kettering to work in NCR’s “Invention Department” and charged him with designing a motor-driven cash register. Kettering succeeded, and that success built a lasting relationship of trust, collaboration and friendship between the two men.

In 1909 Deeds partnered with Kettering in founding the Dayton Engineering Laboratories Company – better known as Delco. Their first breakthrough was an electric ignition system for cars, which eliminated the dangerous hand-crank and made automobiles more accessible and safer for the public. Their innovation quickly caught the attention of General Motors, which bought Delco and brought Kettering on as chief of research. Beyond the electric starter, Kettering developed quick-drying automotive paint, leaded gasoline (later controversial) and advances in diesel engine efficiency.

Deeds and Kettering weren’t just inventors, they were institution builders. Their collaborative spirit gave rise to what became known as the “Deeds Barn Gang,” a group of engineers and tinkerers who worked out of Deeds’ barn on his estate in the early 1900s. There, fueled by curiosity and camaraderie, they developed pioneering solutions that would influence transportation, agriculture and energy. Deeds was also instrumental in forming Wright-Patterson Air Force Base, a hub of aviation research and military innovation to this day. During World War II, Deeds served as chief of aircraft production for the U.S. Army, ensuring that America had the aviation capability it needed for victory.

Going back even earlier, to the mid-1800s, the Barney & Smith Car Company manufactured highquality passenger railroad cars, with a workforce of 1,200. Another Daytonian transformed written communication: Christopher Latham Sholes developed the QWERTY keyboard layout and is credited with inventing the first practical typewriter in the 1860s. The machine was later manufactured by E. Remington and Sons, but Sholes’ innovation revolutionized business and journalism. (As I write this on my MacBook Pro using Sholes’ keyboard layout, I say, “Thanks, Chris!”)

McCall’s – Innovation in Print Scottish immigrant and tailor James McCall recognized that mass-producing dress patterns on tissue paper could empower women to create stylish clothing at home. In 1873 he founded The Queen, a journal dedicated to women’s sewing patterns. By the late 19th century, the Dayton-based journal had evolved into McCall’s Magazine – the Queen of Fashion, blending practical sewing instruction with articles, illustration and domestic advice.

Throughout the 1930s and 1940s the McCall Corporation took on the publication of several notable magazines including Newsweek, Redbook, Scholastic Magazine, The Reader’s Digest and U.S. News. By 1952, the Dayton plant printed 60 national publications – nearly three million magazines were printed and bound daily. The Dayton plant became the largest printing plant in the world with 38 acres under one roof.

By the mid-20th century, its namesake publication, McCall’s, became one of the “Seven Sisters,” the group of dominant women’s magazines in the U.S. It also fostered the careers of writers like John Steinbeck, Ray Bradbury and Fannie Hurst and included Eleanor Roosevelt as a columnist.

The plant was purchased in 1968 by Norton Simon, Inc., which held it for seven years before it was sold in 1975 to the Charter Company. A labor strike led to the ultimate demise of the plant in 1981.

Wright-Dunbar Interpretive Center and Cycle Shop

Across town, the Dayton Aviation Heritage National Historical Park anchors the story of the Wright brothers’ early work. Here, the WrightDunbar Interpretive Center, operated by the National Park Service, explores the brothers’ lives and partnerships along with local Black publisher Paul Laurence Dunbar, a family friend. The centerpiece is the restored Wright Cycle Company, the fourth of the five shops the brothers operated in Dayton. This one is the best preserved, as is the brick street pavers at 1127 West Third Street.

Here the Wrights honed their mechanical skills, earning money repairing and selling bicycles while experimenting with rudimentary flight systems. The Wrights and Dunbar also operated a print shop from 1890 to 1895, publishing newspapers, using period presses and typesetting methods.

The exhibit’s innovations include the development of the first free-fall parachute after World War I, including fabric canopies, deployment tests and high-altitude gear used at McCook Field, an early U.S. Army aviation research and test base located just north of downtown Dayton.

America's Packard Museum

America’s Packard Museum, located in downtown Dayton, is a unique and elegant tribute to one of the most iconic luxury automobile brands in American history. Housed in the beautifully restored 1918 “Citizens Motorcar Company” dealership of art deco design, the museum is both an architectural and automotive treasure.

According to museum curator Stu Morris, in the 1920s, Packards outsold all their competitors combined. “The brand was often called the Rolls Royce of the United States,” he said.

The wealthy were willing to pay handsomely for Packards because of their engineering excellence and luxury. The company introduced many industry firsts, including modern steering wheels, the “H” pattern shift, and the 12-cylinder engine in a production car. Interiors featured rich leather upholstery, handfinished wood and custom detailing. Air conditioning was introduced in the 1940s.

One aspect of the museum that I found particularly interesting were the interpretive panels detailing each car’s history and design features. These placards also noted the price of the car and related it to the average price of other commodities of the time. For example, the 1934 Super Eight Sport Phaeton sold for $3,180, while average yearly wages were $1,600, average new car prices were $700, and a new house was $5,970. Gas was 10 cents a gallon.

“William Harding was the first president to ride to his inauguration, and he did so in a Packard,” Morris said. Other presidents who used Packards included Herbert Hoover, Calvin Coolidge, Franklin Roosevelt and Harry Truman. The Packard was also the “it” car for celebrities including Al Jolson, Clark Gable, Howard Hughes, Charlie Chaplin and Jean Harlow (who posed with the car in publicity shots).

Among its advertising mottos were “Ask the man who owns one,” a line introduced in 1901. In the 1930s, another slogan appeared, “Carriages for the American Gentleman.” Women were relegated to expressing their appreciation of Packard’s luxurious features. But one wealthy woman, Maude Gamble Nippert, the daughter of the inventor of Ivory Soap, always drove her 1934 Super Eight Club Sedan herself.

The collection includes more than 50 vintage Packard automobiles, spanning from the early 1900s to the brand’s final production years in the 1950s.

The first Packard automobile was built in 1899, when brothers James Ward Packard and William Doud Packard partnered with engineer George L. Weiss to form the Packard & Weiss Company. The company was officially founded in 1903 in Detroit, after initially operating in Warren, Ohio, the Packards’ birthplace. James Packard, also a mechanical engineer and inventor, was no doubt influenced by Ohio’s inventive culture, that included not only the Wright Brothers, Charles Kettering and John Patterson, but also Thomas Edison, born in Milan, Ohio, who revolutionized electric lighting. James Packard had a relentless drive to improve technology and inventions of his time. His dissatisfaction with a Winton automobile (also from Ohio) drove him to create the first Packard.

Packard survived the Great Depression by introducing a lower priced car and a production line.

Alas, after World War II, Packard struggled to compete, mostly by failing to modernize its design, and falling behind brands that embraced fins, chrome and flash. In 1954 it merged with Studebaker in a desperate attempt to survive. It failed and the last Studebakers were produced in 1958. But Packards are remembered for how gloriously they once led the industry.

Dayton Art Institute

Dayton’s industrial titans did more than revolutionize transportation and technology, they also helped shape the city’s cultural landscape, leaving a lasting legacy in art, architecture and public spaces.

The Dayton Art Institute, founded in 1919, is home to over 27,000 artworks spanning 5,000 years of history. Visitors can marvel at pieces by renowned artists like Georgia O’Keeffe, Andy Warhol, Edward Hopper, Claude Monet, and Edgar Degas. It owes its existence in part to Julia Shaw Patterson. Carnell, the widow of prominent industrialist Frank Patterson, the brother of NCR co-founder John Patterson.

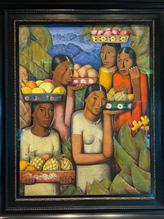

The museum is perched on a hill on the edge of the Great Miami River overlooking downtown Dayton. Its landmark building was designed in Italian Renaissance architectual style by prominent museum architect Edward B. Green of Buffalo, New York and is listed on the National Register of Historic Places. I was so surprised when I ascended the short flight of stairs to the first gallery: the first painting I encountered appeared quite familiar. “Vendedoras de Fruitas “(Fruit Sellers) is a work by Alfredo Ramos Martinez. It was a gift to the museum from Jefferson Patterson, Frank Patterson’s son, in 1959. It was similar to the monumental fresco of nearly 48 feet, “El Dia del Mercado” (Market Day) that was originally painted in 1938 for La Avenida Café and today hangs over the main circulation desk at the Coronado Public Library. Another work by Martinez, “Canasta de Flores” (Basket of Flowers) is on display in the library’s main hall.

The Great Dayton Flood of 1913 was one of the most devastating natural disasters in Ohio’s history and marked a defining moment for Dayton. On March 25, 1913, after days of heavy rain, levees broke, and downtown Dayton was overwhelmed with water as deep as 20 feet. More than 360 people died; 65,000 were displaced and damages exceeded $100 million ($3 billion today).

The most prominent and decisive figure in the rescue and recovery effort was NCR founder John Patterson who mobilized NCR employees to build flat-bottomed rescue boats from the company’s factory wood supply – 300 were launched in 48 hours and the NCR campus became a relief hub.

Newspaper publisher and future governor James Cox used his presses and political clout to rally national attention and raise funds. Deeds and Kettering also helped with relief and recovery and joined Patterson in looking beyond recovery toward long-term flood prevention, spearheading the creation of the Miami Conservancy District in 1914, a locally funded public works project. While its primary mission was flood control, its creation sparked broader conversations and actions around public land use, green spaces and the public park system Dayton enjoys today. Patterson also believed that beauty and nature uplifted urban life and worker morale. In the early 20th century, he transformed NCR’s factory grounds into meticulously landscaped campuses with walking trails and gardens. Hills & Dales MetroPark was developed from land Patterson owned and helped design with the famous landscape firm, Olmsted Brothers, the sons of Frederick Law Olmsted who designed Central Park in New York City. The park opened in 1907 and remains a wooded, scenic escape just south of the city.

Similarly, Kettering and his family supported the whimsical Kettering Children’s Garden at Wegerzyn Gardens MetroPark, and his son Eugene Kettering and daughter-inlaw Virginia helped fund RiverScape MetroPark, a central downtown hub where gardens, riverfront paths and performance venues intersect. In 1957, Marie Aull, widow of printing magnate John Aull, donated her stunning estate and English-style gardens to the city, founding Aullwood Garden MetroPark. Many of these private efforts and land donations laid the groundwork for Five Rivers MetroParks, one of the most respected public park systems in the U.S.

From my top-floor suite at Hotel Ardent, I could look out on Dayton’s downtown and the historic Victoria Theatre just across the street. This is a beautiful property and Dayton’s newest boutique gem, which opened this year and is part of Hilton’s Tapestry Collection. It is housed in the historic Barclay Building, a restored 10-story structure from 1927 that is listed on the National Register of Historic Places. The remodel blends timeless charm with contemporary elegance.

On the ground floor, Bistecca brings a taste of Florence, Italy to downtown Dayton.

After devouring my King Salmon, served over an English pea risotto, with a sumac lemon honey glaze, I asked if executive chef Jacob Rodibough was available to stop by my table. He was there in short order with a ready smile. I told him the dish was exquisite, and he beamed. After working at some of the top steakhouses and bistros in Sarasota, Florida, Jacob shared that he was happy to return north to Ohio, where he has roots in the area. He’s getting to know all the local farmers as he emphasizes locally sourced ingredients along with his wood-fired techniques.

The restaurant had just opened when I visited; a quick check on their current menu shows new offerings that I may just have to go back and try, among them “Chef’s Peppered Prime Strip” a Texas prime, peppered and cooked to order with Chef’s famous brandy cream.” Oh yes, I’ll be back.

The Pine Club

Another restaurant that I was encouraged to hit was The Pine Club, but I was warned to bring cash. To this day, the popular restaurant that has been tucked into a modest brick building near the University of Dayton since 1947 does not take credit cards and only local checks.

But that certainly hasn’t hurt business. I was told that the wait for dinner would likely be an hour, but I could have a seat at the bar. Oh, I forgot to mention that the Pine Club does not take reservations either. The bar was full,

but I cast an eagle eye on those waiting to be called for dinner. It didn’t take long before I was seated and enjoying an Old-Fashioned, which seemed like an appropriately named drink for this venue.

The Pine Club is best known for its dry-aged hand-cut steaks, particularly the bone-in ribeye and filet mignon, but I went with the tenderloin tips with fresh mushrooms and gravy. For my two sides, I chose a baked potato and

green beans. Rolls and butter are served automatically. It was quite a spread, and those tenderloin tips were indeed tender. I passed on dessert, which I hear is often the case at the Pine Club.

Servers here are a bit older and wiser, and especially kind; I sensed most had been there for decades. For visitors, I heartily recommend the Pine Club for a really good meal paired with its authentic Midwestern hospitality.

When you go…

Visitor Information

Destination Dayton(800)221-8235www.destinationdayton.org

Where to Stay

Hotel Ardent137 North Main StreetDowntown Daytonwww.hilton.com

Attractions/Museums

America’s Packard Museum420 South Ludlow Streetwww.americaspackardmuseum.org

Boonshoft Museum of DiscoveryA family-friendly science and natural history museum with a planetarium, hands-on exhibits and a small zoo. 2600 Deweese Parkway www.boonshoft.org

Carillon Historical Park 1000 Carillon Blvd.www.daytonhistory.org

Contemporary Dayton(Known as “The Co”)25 West 4th Streetwww.codayton.org

Dayton Art Institute456 Belmonte Park Northwww.daytonartinstitute.org

Aviation sites

Dayton Aviation Heritage National Historical ParkIncludes the Hawthorn Hill-Wright Mansion, Huffman Prairie Flying Field, Interpretive Center, Paul Laurence Dunbar House, Wright Brothers National Museum, Wright Cycle Company and Wright-Dunbar Interpretive Center. All are run by the National Park Service. 1000 Carillon Blvd. www.nps.gov.daav

Huffman Prairie Flying Field Interprative Center/Wright Brothers Memorial 2380 Memorial Road Wright-Patterson Air Force Base (937)425-0008 www.nps.gov > wrbr

National Museum of the U.S. Air ForceIncludes the co-located National Aviation Hall of FameWright-Patterson Air Force Base www.nationalmuseum.af.mil www.nationalaviation.org

Woodland Cemetery and ArboretumOne of the nation’s five oldest “garden cemeteries,” Woodland is the resting place of The Wright brothers, poet Paul Laurence Dunbar, inventor Charles F. Kettering, and author/humorist Erma Bombeck, among others. www.woodlandcemetary.org

Wright Dunbar Interpretive Center 16 South Williams Street 937 225-7705 www.nps.gov. > places > wdic

Gardens

Cox ArboretumAullwood Gardenwww.metroparks.org

Restaurants

Bistecca137 North Main Streetwww.bisteccadayton.com

The Foundry DaytonAtop the AC Hotelwww.thefoundryrooftop.com

J.D.s Old-fashioned Frozen Custard (Voted Dayton’s Best Ice Cream Parlor for years)322 Union Blvd, Englewood www.jdsfrozencustard.com

Marion’s PiazzaDayton’s best pizza since 1965; several locations www.marionspiazza.com

The Pine Club 1926 Brown Street www.thepineclub.com

Smales Pretzel BakeryHomemade pretzels; a Dayton tradition since 1906 210 Xenia Avenuewww.smalespretzels.com

Events/Festivals

Air Force MarathonWright-Patterson Air Force Base September www.usafmarathon.com

Dayton Air ShowHeld in late June since 1975 3700 McCauley Drive, Vandalia, Ohio www.daytonairshow.com

Dayton Celtic FestivalRiverscape Metro Park,111 Monument DriveDowntown Dayton July 25 – 27, 2025 www.daytoncelticfestival.com

Germanfest PicnicAugust 8-10, 20251400 East Fifth Streetwww.germanfestdayton.com