28 minute read

Dwight D Eisenhower - A Journey Through Legacy and Landscape

From Abilene to Gettysburg and the interstates in between, tracing the enduring mark of the man who led and connected America.

Story and photos by KRIS GRANT

I was just a kid when Dwight D. Eisenhower served as the 34th president of the United States. At that time, I regarded him as an “old man” (he was 62) with thin whitish hair who occasionally appeared on our 18-inch black-and-white TV screen. He was often filmed on the golf course. My dad said that golf was one way the president got some regular exercise after his heart attack in January 1955. Despite this major cardiac event which required weeks of rest, Eisenhower ran for reelection in 1956 and won by an even greater margin than his landslide victory in 1952.

In his memoir, At Ease, Eisenhower noted that due to conversations with his doctor and his own growing health concerns, he quit smoking abruptly in 1949. Before then, he confessed that he regularly smoked four packs a day. To help him break the habit, for several years he famously kept an unlit cigarette in his hand during meetings. (The Surgeon General’s report on smoking didn’t come out until 1964.)

I was too young to realize that he had led our country to victory in World War II as Supreme Commander of the Allied Expeditionary Force. He commanded all Allied operations in Western Europe,

including the planning and execution of Operation Overlord – the D-Day invasion of Normandy on June 6, 1944. But after the war Eisenhower wasn’t ready to retire– he served as president of Columbia University. Then in 1951 President Truman requested that he return to Europe to serve as the first Supreme Allied Commander Europe of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO), an alliance of 12 countries formed to provide collective defense against a growing, nuclear-armed menace, the Soviet Union.

No wonder both the Democrats and Republicans courted Eisenhower to be their presidential candidate in 1952. He ran on the Republican ticket and soundly defeated Adlai Stevenson. It would take me a lifetime of education and living through subsequent presidential administrations

from John F. Kennedy to Donald J. Trump to recognize what a great visionary and leader our country had in Eisenhower, or “Ike” as he was affectionately known.

To learn more about the man, I traveled twice to Abilene, Kansas, now home to the Dwight D. Eisenhower Presidential Library, Museum and Boyhood Home, and to his retirement home, a farm in Gettysburg, now a site run by the National Park Service. In making these cross-country trips, I often traveled on highways that are part of the officially named Dwight D. Eisenhower National System of Interstate and Defense Highways, or what we typically refer to as “the Interstates.”

Getting that massive highway project approved by Congress was a feat in itself. It remains the largest public works project in our nation’s history.

One more note: during his presidency and after, Ike and First Lady Mamie wintered at a private residence in Rancho Mirage, loaned to them by Paul Helms, a wealthy baking magnate and founder of Helms Bakery. (Oh, I do fondly remember those Helms Bakery trucks that tooted their horns as they rolled throughout Southern

California with their wooden drawers in the back filled with fresh baked goods.) The Helms residence was at the Thunderbird Country Club where the desert climate was ideal for Eisenhower’s heart condition and where he could enjoy playing golf on one of the first courses built in the Coachella Valley. The Eisenhower name lives on in the region through the respected Eisenhower Health Medical Center in Rancho Mirage, opened in 1971, two years after Ike’s death.

In Eisenhower’s Farewell Address to the Nation, delivered Jan. 17, 1961, these words proved to be prophetic and perhaps a lesson we are still learning:

As we peer into society’s future, we… must avoid the impulse to live only for today, plundering for our own ease and convenience, the precious resources of tomorrow.

So, let’s look at the various roads traveled by this remarkable man who led our country in what was, comparatively speaking, a time of national unity.

Abilene, Kansas, “The Heart of America”

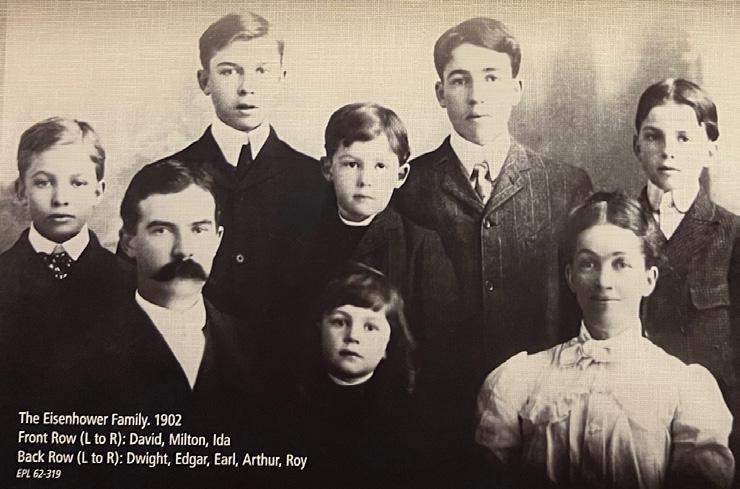

Dwight D. Eisenhower came from a family of seven boys (the second oldest child, Paul, died in infancy). His father David first ran a general store in Hope, Kansas. He later worked for the railroad in Denison, Texas, where Dwight was born, before settling the family in Abilene when Dwight was just a toddler. The Eisenhowers raised their six sons first in a small house that David’s father gave them, then in a larger home that they purchased from David’s brother. While larger, it was still small and “on the wrong side of the tracks.” The Kansas Pacific Railway ran through downtown Abilene and served as the class dividing line of the city. The Eisenhower home, at the corner of Chestnut and East South 4th Street, was in the less affluent part of town both ethnically and racially.

The well-to-do and growing middle class lived north of the tracks. And Abilene did have wealth – in the 1860s, it was a cowtown at the end of the Chisholm trail. Wild Bill Hickock was once the town marshal. Entrepreneur and philanthropist C. L. Brown founded the Abilene Electric Light Works in 1898 and the Brown Telephone Company in 1899 – a business that played a key role in forming what eventually became Sprint Corporation.

While the Eisenhowers’ lifestyle was modest, theirs was a loving home, characterized by discipline, education, ambition, simple pleasures and religious faith. The family said prayers before meals and held family Bible study nearly every evening.

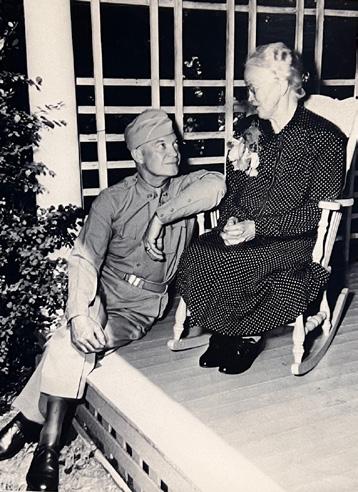

Ike attributes his mother Ida as being the “greatest personal influence on my life.” While Ida worshiped with the “Bible Students,” a forerunner of the Jehovah’s Witnesses, the boys were encouraged to find their own paths of faith.

When it came time to attend college, Ike realized his working-class family with limited means couldn’t afford to send all their sons to college, but military academies offered a free, high-quality education along with room, board and a guaranteed job upon graduation.

Being fascinated with the sea and ships, Ike originally planned to join the Navy and sought an appointment to the Naval Academy at Annapolis, but he learned that he exceeded the maximum age limit by a matter of months. This was a result of a fall and severe knee injury when he was five years old that put him back a year in school. In the early 1890s, antibiotics had not yet been invented and when an infection from his injury worsened and spread, a doctor suggested amputating his leg. But Ida wouldn’t allow it; she nursed Dwight back to health with home remedies and careful attention.

The injury helped shape his character, allowing him to endure pain and hardship without complaint. In At Ease, he wrote, “I clearly recall the night when I lay in bed sobbing because I could not go out trick-or-treating. My mother came and sat beside me for a long time. Finally, she said, “Dwight, if you can’t control your temper, how do you expect to control anything in life?”

He called that a turning point in his emotional development, and wrote in his memoir, “That night, I think I began to learn the value of self-discipline.”

During their boyhood and early teens, the Eisenhower boys handled all manner of indoor and outdoor chores around the house. Additionally, their father gave each of them small plots of land to cultivate however they chose, with the understanding that they could sell what they raised in town and use the money as they liked. This instilled in them a sense of independence, responsibility and entrepreneurship from an early age. For Ike, it helped shaped his strong work ethic and self-reliance. In the summer, he grew sweet corn, watermelon and vegetables, which he sold to neighbors and brought into town by wheelbarrow. When the growing season was over, Ike hit on a novel idea: He asked his mother for her tamale recipe, then whipped them up himself, wrapping seasoned meat and spices in cornmeal dough and steaming them in husks in the family kitchen and then making the rounds in town to sell his savory treats.

Ike later worked summers at the Belle Springs Creamery, where his father worked as an engineer and mechanic. Ike cleaned out boilers, shoveled coal into the furnaces and handled heavy loads of milk cans and ice. The grueling work paid about $10 a week, which he mostly turned over to his family.

The Eisenhower Museum in Abilene is one of the finest presidential museums I’ve visited. It traces every step of Eisenhower’s life – his childhood years, schooling, military career throughout two World Wars, presidency and more. Here, you’ll find his boyhood home and his and Mamie’s final resting place.

From West Point to Supreme Commander to President

Eisenhower graduated from West Point in June 1915, as part of a class that would later be celebrated as “the class the stars fell on,” due to the high number of generals it produced.

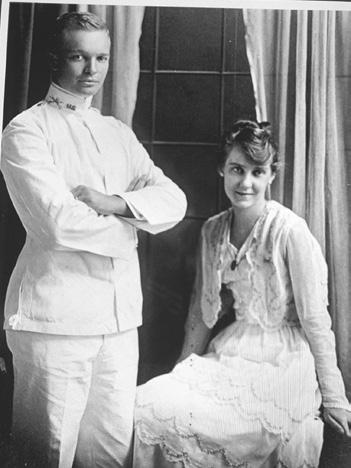

His first assignment was at Fort Sam Houston in San Antonio, Texas, with the 19th infantry. There he met the vivacious Mamie Doud who hailed from a wealthy Denver family who always vacationed in Texas to escape the cold Colorado winters. They married the following year.

The Eisenhowers welcomed their first son, Doud Dwight Eisenhower in 1917 but he tragically passed away in 1921 of scarlet fever. After this heartbreaking loss, Dwight and Mamie welcomed a second son, John, in 1922. John eventually had four children and the Eisenhowers doted on them.

Though not initially assigned to a combat role during World War I – a deep disappointment to him – Eisenhower was stationed at training camps, including Fort Oglethorpe and later Camp Colt in Gettysburg, Pennsylvania, where he commanded a tank training center, despite never having seen a tank before.

In 1919, as a junior officer, he was assigned as a logistics officer from the Tank Corps to assess military mobility across U.S. roads on a transcontinental convoy. The convoy drove across the country in trucks and other military vehicles mostly along the Lincoln Highway, to test mobility and demonstrate the need for better roads.

Both at Camp Colt and on the convoy, Eisenhower’s skill in logistics and training quickly set him apart.

After World War I ended, Eisenhower focused on broadening his military education. He attended the Command and General Staff College at Fort Leavenworth, graduating first in his class in 1926. This achievement marked him as a rising talent within the U.S. Army. Over the next decade, Eisenhower held a series of staff

assignments that allowed him to observe, learn from, and work with top Army leaders, most notably General John J. Pershing, General Fox Conner whom he called “the ablest man I ever knew” and later General Douglas

MacArthur. Conner, who mentored Eisenhower while they were stationed in Panama, deeply influenced his views on leadership, coalition warfare and the importance of history in military strategy.

Serving as MacArthur’s chief of staff, Eisenhower helped develop the Philippine military forces and observed firsthand the geopolitical tensions brewing in the Pacific.

Yet, when World War II erupted, Eisenhower was still a relatively unknown colonel. But after the attack on Pearl Harbor in December 1941, he was brought to Washington and assigned to the War Plans Division under Army Chief of Staff General George C. Marshall. Eisenhower impressed Marshall with his analytic skills, calm under pressure and deep understanding of logistics and coalition strategy. Within months, he was promoted to brigadier general and then major general, as he took on greater responsibilities for planning global operations.

In 1942, Eisenhower was sent to London as Commander of U.S. Forces in the European Theatre. Shortly afterward, he was appointed to lead Operation Torch, the Allied Invasion of North Africa. Despite complex political challenges and the difficulties of coordinating British, American and Free French forces, Eisenhower managed the campaign effectively. His diplomacy and steady leadership helped build trust among the Allies.

Following success in North Africa, Eisenhower led the invasions of Sicily and mainland Italy. Each operation strengthened his reputation as a strategic thinker and a leader capable of managing multi-national forces. In December 1943, Eisenhower was selected as Supreme Commander of the Allied Expeditionary Force.

The appointment marked the pinnacle of his military ascent. As Supreme Commander, Eisenhower bore the ultimate responsibility for the largest amphibious invasion in history, Operation Overlord. He coordinated not only military strategy but also the egos and politics of British commanders like Bernard Montgomery, American generals like George Patton and Omar Bradley and national leaders like Franklin Roosevelt, Winston Churchill and Charles de Gaulle.

It was Eisenhower who made the bold final decision to proceed with the D-Day invasion despite weather doubts on June 5, 1944. The invasion was successful in maintaining surprise and establishing a Western front. Within weeks, hundreds of thousands of troops and tons of supplies were landed. It marked the beginning of the end for Nazi Germany, forcing Hitler

to fight a two-front war – against the Soviets in the East and the Allies in the West.

After intense fighting in places like the Normandy hedgerows and the Battle of the Bulge in the heavily wooded Ardennes region of northern France and Belgium, Germany surrendered on May 7, 1945 – about 11 months after the D-Day invasion. By war’s end, Eisenhower was one of the most respected military leaders in the world – a soldier’s general, and a future president in the making.

“Peace through Prosperity” and the building of the

Eisenhower accomplished much during his presidency. Under his leadership, the Korean War ended just months after he took office. School desegregation began in 1957, when Eisenhower sent federal troops to Little Rock, Arkansas to enforce the Supreme Court’s ruling in Brown v. Board of Education. He also welcomed Alaska and Hawaii as our 49th and 50th states. Alaska was admitted on Jan. 3, 1959, and Hawaii on Aug. 21, 1959.

In addition to these accomplishments, Eisenhower’s most monumental infrastructure achievement was the creation of the Interstate Highway System.

Inspired in part by Germany’s autobahns and his own grueling 1919 cross-country Army convoy, Eisenhower envisioned a network that would enhance national defense, boost commerce and connect Americans like never before. Americans were taking to the highways in record numbers. In 1950, there were 40.3 million passenger cars on the road; by 1960, there were 61.7 million.

The first bill aimed at creating an interstate system was introduced in

1955, but it failed due to disagreements over how to fund the massive program. But Eisenhower kept pushing. The successful Federal-Aid Highway Act of 1956 was passed with bipartisan support on June 29, 1956, a time when both houses of Congress were controlled by Democrats. Part of its success was due to a “user pays” funding mechanism –the Highway Trust Fund – which used a dedicated 3 percent tax on fuel, tire and vehicles to pay for construction.

While promoted to improve safety and commerce, the act’s success was also tied to Cold War anxieties. Highways would allow for mass evacuations from cities in the event of a nuclear attack and ensure rapid military mobilization.

While promoted to improve safety and commerce, the act’s success was also tied to Cold War anxieties. Highways would allow for mass evacuations from cities in the event of a nuclear attack and ensure rapid military mobilization.

I can readily understand how a jittery public would support this legislation –as a child in elementary school in the mid-1950s, I participated in “Drop” drills, wherein a series of bells would ring, our teacher would yell “Drop!” and we would leap under our desks and cover our heads with our arms. I doubt these actions would have helped much in the face of an atomic bomb, but they certainly did promote high anxiety and nightmares.

Eisenhower’s landmark legislation authorized the construction of 41,000 miles of interstate highways over a 20-year period. The total projected cost was $25 billion. Yet building a national system was anything but smooth. The final cost exceeded $130 billion ($600 billion in today’s dollars) stretched 48,000 miles and required 36 years of construction (1956 – 1992). It involved millions of workers and thousands of construction firms working in every state and remains the largest public infrastructure project in our nation’s history. Nothing else in American history – not the transcontinental railroad, the Hoover Dam, the New Deal programs, or the Apollo missions – matches it in scale, duration, or cost.

Once the bill passed, construction began quickly. The first project broke ground near St. Charles, Missouri in August 1956 on what would become Interstate 70. Some parts of the system, including sections of the Pennsylvania Turnpike and the New Jersey Turnpike, were already in place and incorporated into the system.

The highway system was designed to have standardized features across states – minimum lane widths, shoulder specifications, limited access points and cloverleaf interchanges. These uniform standards were crucial in ensuring consistency, safety and efficient travel from coast to coast.

East-West routes were given even numbers, with the lowest numbers in the South, such as I-10, which

runs from Santa Monica, California to Jacksonville, Florida, while I-90 runs nears the Canadian border. North-South routes have odd numbers, such as I-5 running along the West Coast and I-95 runs from Maine to Florida along the East Coast. Auxiliary or Spur roads are three-digit numbers, with the last two digits matching the main interstate they’re connected to, such as I-405 that loops around Los Angeles and is connected to I-5. Note: there is no I-50 or I-60. These numbers were skipped because there were already well-known U.S. Highways 50 and 60, which ran across the country, and planners wanted to avoid confusion,

The Eisenhower Tunnel, officially called the Eisenhower – Edwin C. Johnson Memorial Tunnel, carries Interstate 70 under the Continental Divide in the Rocky Mountains. Construction began in 1968, and the first bore was completed in 1973, making it the highest vehicular tunnel in the U.S. at an elevation of 11,158 feet. A second bore, named for U.S. Senator Edwin C. Johnson, opened in 1979. The project faced immense challenges due to high altitude, unstable rock, and extreme weather. It cost far more and took much longer than expected, but it finally created a vital year-round link between Denver and western Colorado.

The last leg and final major segment of the Interstate Highway System through Glenwood Canyon in the Rocky Mountains opened in 1992. It was one of the most difficult and expensive highway systems ever built, taking 12 years and $500 million to complete. Engineers had to balance infrastructure needs with environmental preservation – the canyon is narrow, geologically unstable and home to the Colorado River. The final design features elevated roadways, tunnels and bridges that minimize environmental impacts and preserve scenic views as the highway threads its way through the canyon. It is one of the most beautiful scenic highways I’ve ever traveled, and I highly recommend it.

Eisenhower’s Gettysburg: A Home of Memory, Meaning and Quiet Power

When Eisenhower retired from the presidency in 1961, he and Mamie went home to a home in Gettysburg, Pennsylvania. Unlike the lavish postpresidency retreats chosen by some modern leaders, the Eisenhowers settled into a 189-acre property bordering the historic Civil War battlefield – a place that embodied both personal history and national symbolism.

Eisenhower’s connection to Gettysburg began when his West Point class visited the town and its historic battlefields during his junior year at the military academy. That 1914 visit to such historic sites as Little Round Top and Pickett’s Charge left a deep impression on the third-year cadet.

A young Lt. Dwight Eisenhower was sent to Gettysburg in March 1918 to command Camp Colt, the U.S. Army’s first tank training school. At just 25 years old, Eisenhower was handed enormous responsibility. The army gave him no tanks – only recruits, a dusty field and orders to train the nation’s first tank corps soldiers for battle in Europe. This formative assignment left a lasting impression on Eisenhower on the challenges and urgency of war, albeit surrounded by the quiet beauty and hallowed ground of the countryside.

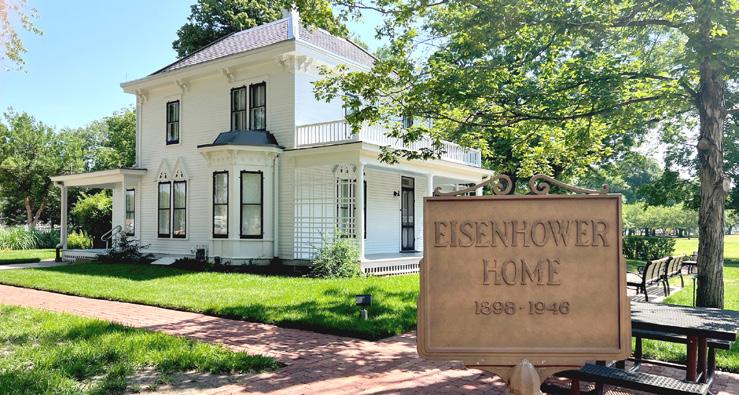

In 1948, while Eisenhower was serving as president of Columbia University in New York and contemplating eventual retirement from public life, he and Mamie returned to Gettysburg to search for a permanent home. They bought the run-down Redding farm on the edge of the Gettysburg battlefield. It was their first and only home purchase in their 53-year marriage.

Eisenhower was always a student of history. Today, the National Park Service maintains his 1,100 volumes, many dealing with the American Revolution and Civil War at the home. It was not surprising that he was drawn to Gettysburg for personal and patriotic reasons. The town’s most famous chapter – the Battle of Gettysburg in July 1863 – marked the turning point of the Civil War and the preservation of the Union. Abraham Lincoln’s Gettysburg Address, delivered just months later, shaped the soul of American democracy.

Eisenhower admired Lincoln immensely, and his portrait hangs in his small private office at the Gettysburg home. Settling in Gettysburg was for Eisenhower both a statement of humility and a salute to enduring American values.

But the farm was also a working place, with Eisenhower taking great pride in raising Angus cattle, mending fences and overseeing the land. Farming, he said, helped keep him grounded after decades of war and politics.

As president, Eisenhower often visited his home, using the farm as a functioning retreat and a way to conduct diplomacy in an informal, personal setting. Here he hosted British Prime Minister Winston Churchill and Soviet Premier Nikita Khrushchev. There were no grand ballrooms, just sun porches, long walks and conversations over coffee.

Eisenhower wrote his memoirs –Crusade in Europe and At Ease – and also took up painting at the farm where he lived much of the year until his death in 1969; Mamie remained there until her passing in 1979, at which time the estate was turned over to the National Park Service, and tours began the following year.

The house remains largely as it was during the Eisenhowers’ years – modest, practical and deeply personal.

Today, tours of the Eisenhower home include the Eisenhower bank barn, built in 1887. Visitors can step inside an old cinderblock milk house that Secret Service agents used as an office space during Eisenhower’s presidential and retirement years. (When Eisenhower first retired, he had no Secret Service protection. That changed after the Kennedy assassination.) On days when staffing allows, the doors to the Eisenhower garage are opened to give visitors a close look at the vehicles Ike and Mamie used in Gettysburg. Included in the collection is a 1955 Crown Imperial limousine used by the President and First Lady. Visitors can also walk to the neighboring property of W. Alton Jones, which Eisenhower used for his prized Black Angus show herd.

When You Go… Abilene, KansasGeneral Information

Abilene Convention & Visitors Bureauwww.abilenekansas.comAbilene Visitors Center201 NW Second StreetOpen Monday – Friday, 10:30 a.m. – 2:30 p.m.

Getting There

If you drive, take 1-15 north to I-70. It’s a 1,535-mile road trip; plan to stop along the way – perhaps Las Vegas, then Grand Junction, Colorado, then Denver.

If you fly: I recommend flying into Wichita Dwight D. Eisenhower National Airport, then driving 95 miles to Abilene. Several major carriers service this airport.

Recommended Restaurants

Amanda’s Bakery & Bistro302 N. Broadway(785) 200-6622

Brookville LegacyA destination dining experience, serving dinners on Thursday, lunch and dinners on Friday, Saturday and Sunday. Choose from Brookville’s Chicken Skillet or Munson Steaks (four types) dinners, both served with hand-peeled mashed potatoes and cream gravy, cream-style corn, cole slaw, baking powder biscuits and homemade ice cream. www.legacykansasabilene.com

Museums and Attractions

The Seelye MansionThree-story Georgian-Revival home with furnishings that mostly originate from the 1904 St. Louis World’s Fair. Original Edison lights, Tiffany accents. 90-minute public tours.1105 Buckeye Avenue(785) 263-1084

Dwight D. Eisenhower Library, Museum and Boyhood HomeOne of 16 Presidential Libraries operated by the National Archives and Records Administration.Open Tuesday – Sunday, 9:30 a.m. – 4:30 p.m. Excellent gift shop. Campus grounds open sunrise to sunset daily. 200 SE 4th Street www.eisenhowerlibrary.gov

Dickinson County Heritage Center

Learn about the county’s famous former residents from C.L. Brown, whose telephone company eventually became known as Sprint, to Abilene’s former town Marshal Wild Bill Hickok. Take a whirl on the 1901 C.W. Parker Carousel, believed to be the oldest operating Parker carousel in existence. The carousel is hand-carved featuring 24 horses and four chariots. The Heritage Center is just a block away from the Eisenhower Library. www.heritagecenterdk.com

Great Plains Theatre

A professional year-round equity theatre company, serving as the only paid actors theatre between Denver and Kansas City along I-70. Showcasing family friendly and main-stage productions. www.greatplainstheatre.com

Greyhound Hall of Fame www.greyhoundhalloffame.comAntique Shopping

Abilene is home to more than 150 antique vendors. Find their specialties and locations at the Abilene CVB’s website (above).

Recommended Hotels

Abilene’s Victorian Inn Bed and BreakfastBuilt by the father of Ike’s childhood friend, Edward Hazlett. Seven rooms in the heart of the historic district.www.abilenesvictorianinn.com

Diamond Motel AbileneOriginally listed in the “Green Book,” it’s where I stayed. Understated, clean and comfortable.1407 NW 3RD Street (785) 263-2360

Holiday Inn Express & SuitesJust off I-70 at Abilene, this relatively new property features an indoor pool.(785) 576-9933www.ihg.com

Engle House Bed and BreakfastOn the National Register of Historic Places, this small B&B was the former home of Jacob Engle. When Ike’s father, David Eisenhower came to Abilene after refrigeration school in Texas, he started working for Jacob Engle at the Belle Springs Creamery where Jacob was Vice-President. Ike also worked for Jacob Engle during the summers until his appointment to West Point in June 1911. As President of the School Board, Jacob Engle signed Ike’s high school diploma. www.englehouse.com

Gettysburg, Pennsylvania

General Information

Destination Gettysburg Adams County, PA www.destinationgettysburg.com

Getting ThereFly into Harrisburg International Airport (MDT), with numerous daily flights. Gettysburg is 40 miles away. Or fly into Baltimore/ Washington International (BWI); 55 miles away with good flight frequency and price options.

Recommended Hotels

Brickhouse InnThis blended 1830 residence and 1898 Victorian home bears battle scars from the war www.brickhouseinn.com

Federal Pointe InnThis blended 1830 residence and 1898 Victorian home bears battle scars from the war www.brickhouseinn.com

Hotel GettysburgLocated on Lincoln Square in the heart of downtown Gettysburg, the hotel features 119 rooms, some with fireplaces; fitness center. www.hotelgettysburg.com

Lightner Farmhouse B & BAn 1862 Federal-style house on 18 acres just two miles from the Gettysburg National Military Park www.lightnerfarmhouse.com

The Swope ManorA beautifully preserved 1836 mansion www.swopemanor.com

Eisenhower National Historic Site

The former home and farm of President Dwight D. Eisenhower and First Lady Mamie Eisenhower is located about 2.5 miles from Lincoln Square in the town center of Gettysburg.

While I was able to drive to the site, during the busy summer season, access is restricted and visitors must take a shuttle from the Gettysburg National Military Park Museum & Visitor Center, where parking is also free.

Park staff lead Eisenhower home tours on Thursday, Fridays, Saturdays and Sundays for the Summer 2025 season May 29 - August 31. Home tours are offered at 10 a.m., 11

a.m., 12 noon, 1 p.m. and 3 p.m. Tours also operate during the spring and fall with more limited time slots and special holiday tours occur in December. Check the National Park Service website for updated information. House tours are free and available on a first-come, first-served basis. Tours are limited to 40 visitors. The grounds of Eisenhower National Historic Site are open seven days a week, from sunrise to sunset.

243 Eisenhower Farm Road www.npw.gov (then enter “eise”)

Recommended Restaurants

Alexander Dobbin Dining Rooms www.Dobbinhouse.com

Meade and Lee Fine Dining and Sweeney’s TavernA Civil War-period dining experience featured period fare served by period-dressed servers. www.farnsworthhouseinn.com

Pointe Pubwww.federalpointeinn.comHickory Bridge Farm Restaurant15 miles west of Gettysburg, genuine farmto-table food served at tables outfitted with linen and China in a historic barn. www.hickorybridgefarm.com

The Sign of the Buck Modern brasserie serving New American cuisine with local flair. www.signofthebuck.com

Gettysburg National Military Park Museum & Visitor Center

Exhibits on the Civil War, the 1884 Gettysburg Cyclorama, theater, bookstore, restaurants.

The museum serves as a starting point for licensed battlefield guide-led bus tours and shuttles to the Eisenhower National Historic Site.

1195 Baltimore Pike

Open daily: March – November, 8 a.m. – 5 p.m. December – February, 9 a.m. – 4 p.m. www.nps.gov (then enter “gett”)