7 minute read

Jackrabbit As Big As Dogs - Coronado's Early Jackrabbit History

By JOE DITLER

In the beginning there were rabbits for as far as the eye could see – husks of jackrabbits from shore to shore. History has overlooked this massive influence on early Coronado’s development, until now.

Two centuries ago, bands of Kumeyaay Indians roamed what we now know as Coronado. Several lived on the island, which is what Coronado was in those days. We were separated to the north by a river known to modern man as the Spanish Bight. To the south, the strand of land connecting us to the mainland was frequently washed out – a veritable slough.

Kumeyaay lived and hunted on Coronado, using handmade reed boats to transit back and forth from the mainland via water, and they ventured offshore in the ocean seeking food. Coronado had good hunting and fishing in those days, and plenty of fresh water from an underground river.

Part of a young Kumeyaay warrior’s rite of passage was to outrun and catch a wild rabbit, on foot.

Western man arrived on Coronado in the late 1800s and created his own version of rabbit hunts – with a shotgun and a pack of dogs.

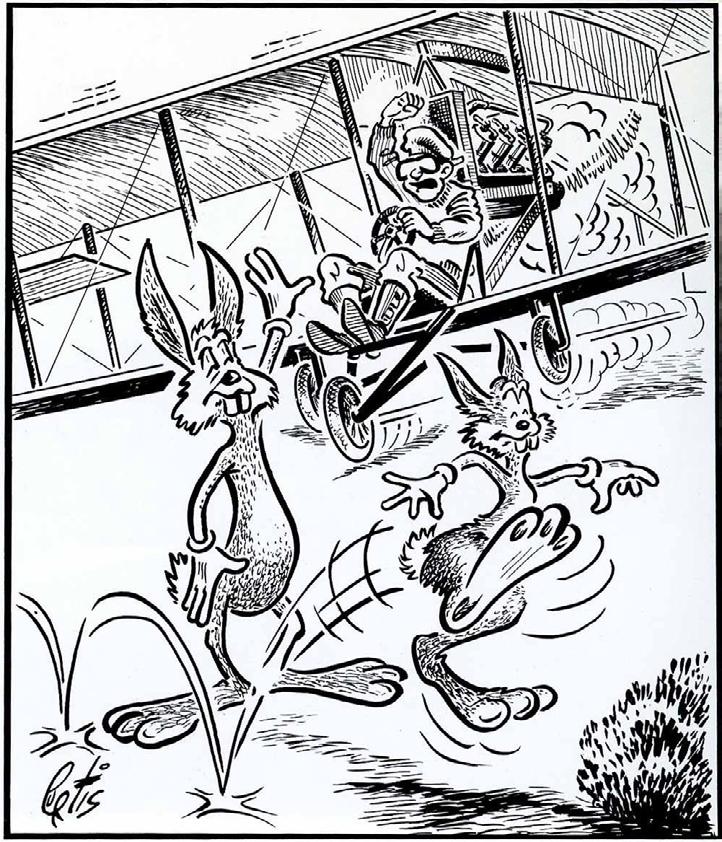

Since as early as 1900, history records large groups gathering on North Island with horses, wagons, a chuck wagon to serve food, and dozens of finely dressed men and women out to hunt the easy prey. When North Island developed as a home to airplanes (1910), the enormous and unchecked populations of rabbits became a hazard to aviation. Small bi-winged airplanes held together with canvas and wire, and sporting tiny wheels for landing gear, proved no match for the madly scrambling jackrabbits inhabiting the eventual runways.

Before long jackrabbit roundups were an annual routine on North Island, designed to flush out the long-eared critters from Manzanita brush found on the island, and to thin their ranks.

Town fathers found out the hard way that rabbits liked the vegetation (Orange trees) planted along Orange Avenue and throughout the fledgling town; and later, the flowers surrounding the officers’ quarters on North Island.

During roundups everyone turned out. It was an all-hands exercise that found Army, Navy and civilian personnel lined up near the Spanish Bight equipped only with sticks and clubs.

On command, the legion of men (pilots, mechanics, cooks, officers, enlisted men and anyone who could stand) walked forward in a line while beating their sticks. Rabbits began to pop out everywhere and flee from the hunters’ unrelenting progression.

Before long rabbits were so thick on the ground that people would step out of the line to take a swipe at a rabbit’s head, knocking him unconscious. By the time the line got to the water (the northwest side of North Island), hundreds of rabbits had been clubbed to death, while hundreds more were forced into the water to drown.

Their carcasses, according to Elretta Sudsbury, author of “Jackrabbits to Jets” (the complete history of North Island), were hauled to the San Diego Zoo (after 1915) for use in feeding the animals. Sudsbury also describes another method for thinning the ranks of rabbits. These were called the Ford Rabbit Derbies. “The first derby was held on Saturday, May 26, 1928,” said the author.

“Seventeen men in Model T ‘Tin Lizzies,’ competed. Rules allowed two runners per ‘Lizzie.’ No weapons other than clubs were allowed. Each contestant followed a course across Rabbit Plateau thru the morning mist, across the landing field, and back to the finish line, which was abreast of the VT-2 landplane hanger on West Beach.”

In the 1928 race, Lieutenant Greber in the “Red Peril” won first prize, which was a five-gallon loving cup, a medal, and a bouquet of carrots and beets … plus $5. Prizes, according to Sudsbury, were presented by Miss Bessie Love, a silent film star of the time.

This next anecdote is so unbelievable; I’ll let Elretta Sudsbury tell it in her own words:

“During one Ford Derby, the winner lucked out. He chased a rabbit over sand dunes and through the brush for a long time, not gaining much, but wearing the rabbits down. In the meantime, other contestants were doing likewise.

“The rabbit chaser’s car broke down so he crawled under it, peering at its innards, trying to find the trouble. A winded jackrabbit took shelter under the car in an attempt to escape another pursuer, and the would-be mechanic grabbed him. The car was started and the derby won.”

If you’ve never seen a jackrabbit in flight, it’s difficult to describe just what they go through to avoid capture. The late Bruce Muirhead once told me a story about his father, Clarence, as was described during one rabbit hunt in 1931. The author of the article, which appeared in Sports Afield and Trails of the Northwoods, used aeronautic terms of the time to describe how Muirhead’s Greyhounds - Charles, Girlie, Rex, Fawn and Stupid – put rabbits through their paces:

“These particular jackrabbits seem to be well schooled in aerial acrobatics,” said the writer. “Looping the loop, side slipping, Immelman turns, and tail spins are mere items of their stock in trade. These acrobatics confuse the dogs to such a degree that Jack frequently gives the entire pack the slip.”

Occasionally I’m asked to give a tour of Coronado, to discuss history of the island with either first-time visitors or a In the water there lived lobsters so old and large that, when a Kumeyaay Indian grabbed one, the lobster thought he had the Indian, until a second set of hands helped pull the spiny creature into the reed boat, or ashore.

Abalone existed just offshore and in tide pools. Sea bass that must have been a century old (none of these critters had natural predators until the Western world collided with the Native American tribes at the end of the 19th century) weighed in at 400 pounds. It was indeed a hunters’ paradise.

Organized rabbit hunts are mentioned throughout the history of the Kumeyaay Nation. Chasing the illusive rabbit appeared more as organized slaughter throughout the 1920s and 1930s. The last recorded “hunt,” or Roundup, took place in 1940.

To this day, I’m happy to report that, while night driving into the key at Sunset Park, or through the Country Club area of town; when you turn off your lights, wait a moment, and then turn them back on; you’ll see the rabbits here and there along the fence or in the grass, detectable by the reflection in their big eyes.

If Bugs Bunny taught us nothing else, it’s that, in the end, the wily wabbit always wins.

NOTE: Joe Ditler is a long-time writer, author and historian known as the “Coronado Storyteller.” He is a former editor of CORONADO Magazine, past executive director of the Coronado Historical Association/ Museum and prior director of the San Diego Maritime Museum. His capturing of history, memories and anecdotes will be appearing semi-regularly in future editions of CORONADO Magazine.