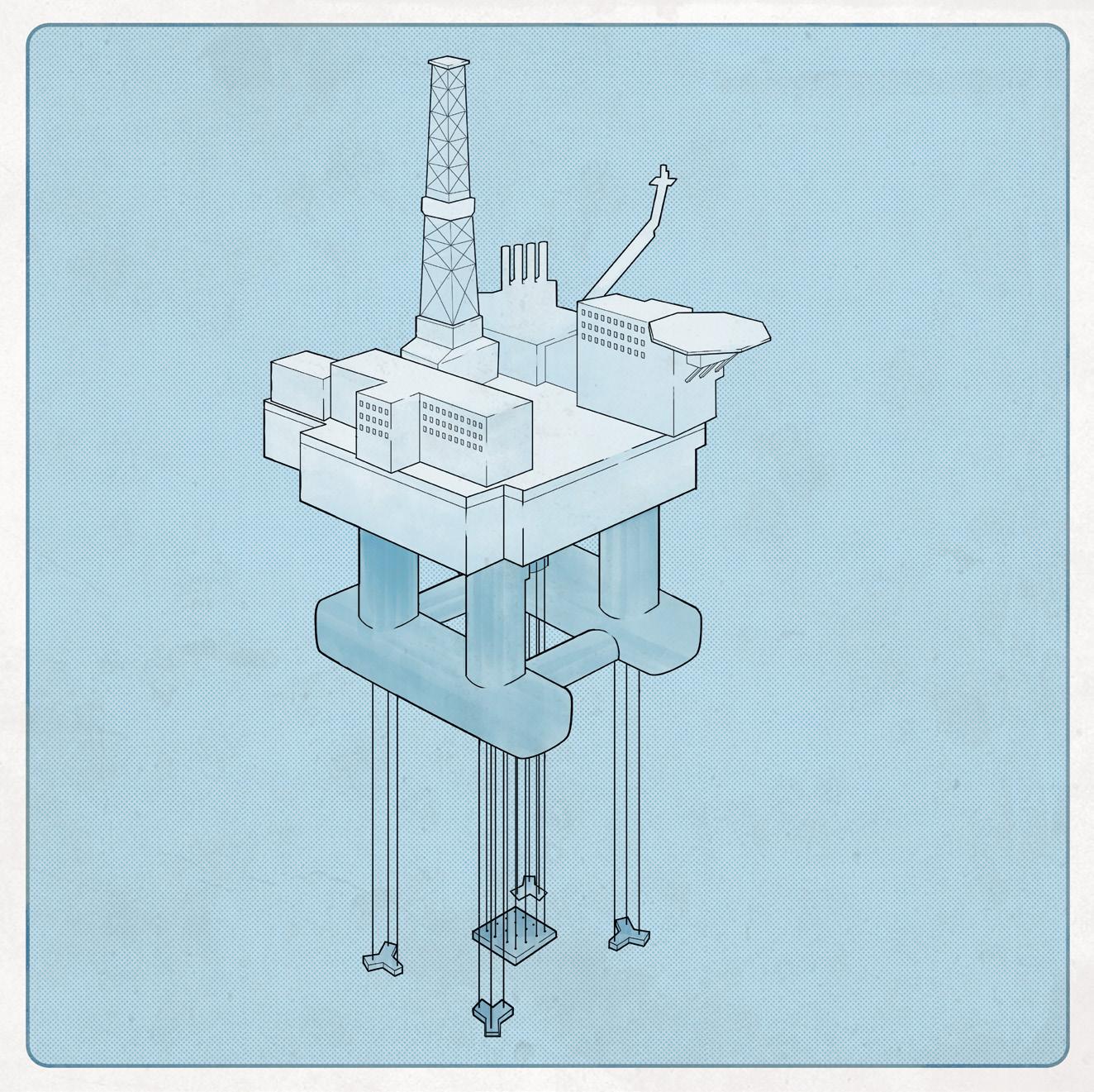

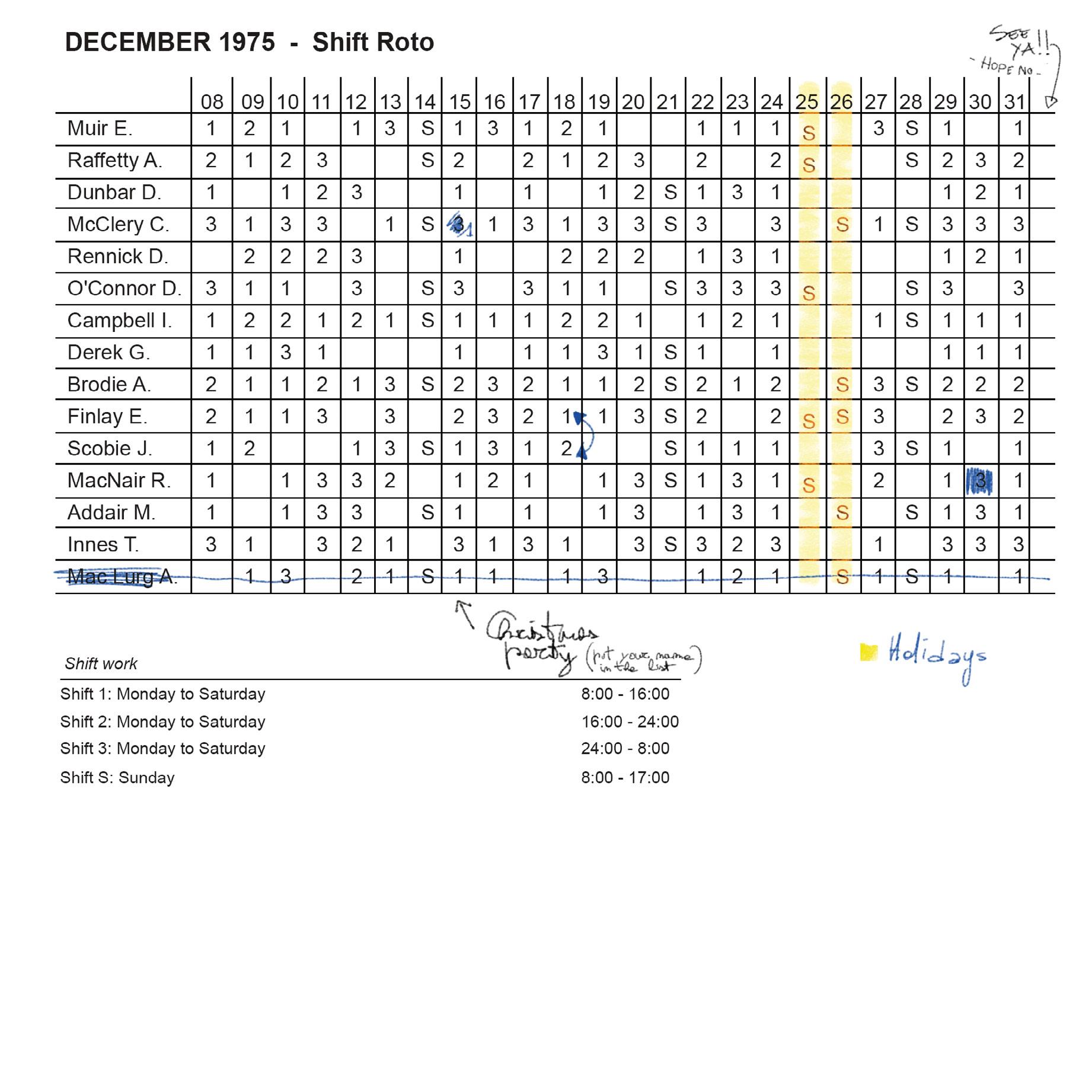

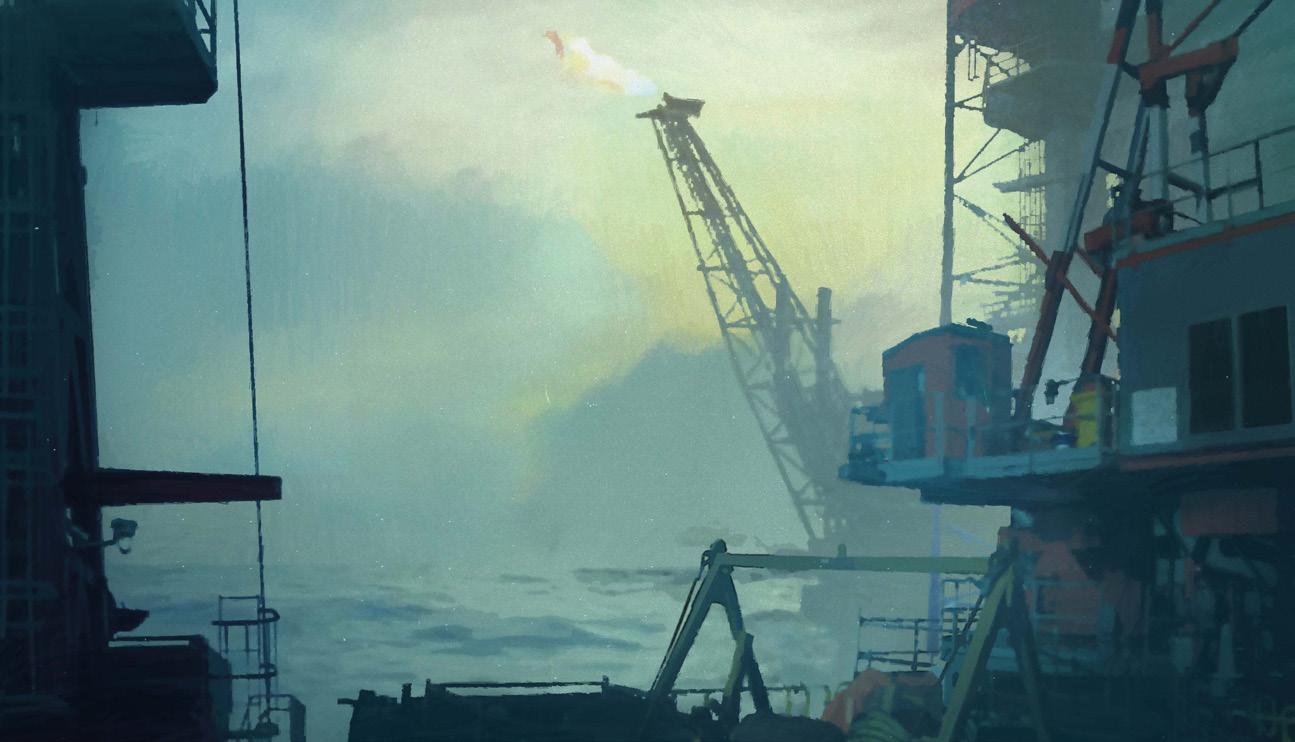

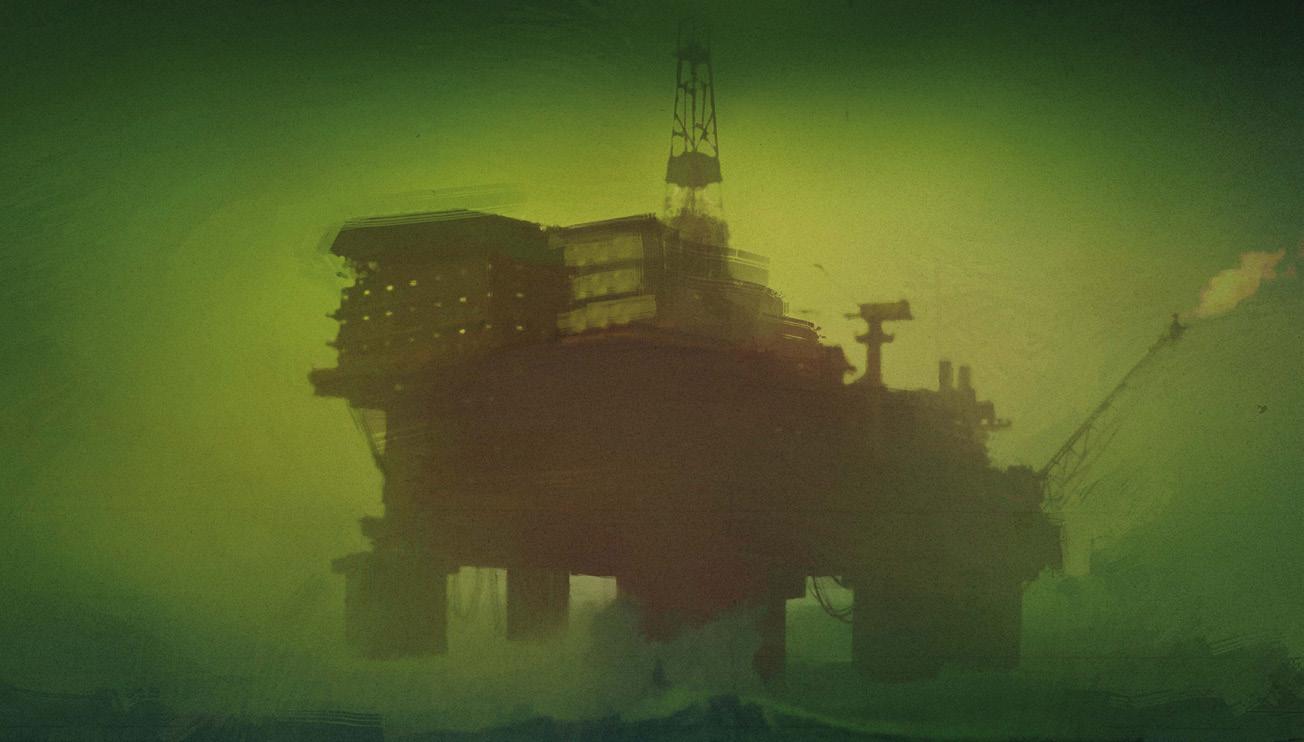

When it comes to ideal settings for a horror game, an oil rig ticks all the right boxes. “It’s almost like a spaceship,” lead designer Rob McLachlan begins, before getting more specific. “It’s like a haunted spaceship, which is a very common trope in many horror movies. And it has commonalities, obviously, with the Antarctic research station in The Thing.” Like the setting for John Carpenter’s classic sci-fi horror, the sheer isolation of the Beira D oil rig in Still Wakes the Deep adds immeasurably to the game’s tension – it’s hard to think of many worse places to be trapped with something that wants to kill you. Yet it’s also strangely beautiful: a stark tower of steel emerging incongruously from the ocean. “Go on Google Image Search and you can find the most incredible photography of platforms from around the world,”

McLachlan says. “And seeing these monoliths sitting in a rough sea with waves breaking on them, these grey-yellow metal hogs suspended above the ocean, it was like: wow, we’ve got to make that work. It’s such an atmospheric place that it seems almost a given that it would draw people in, because it’s so unique.”

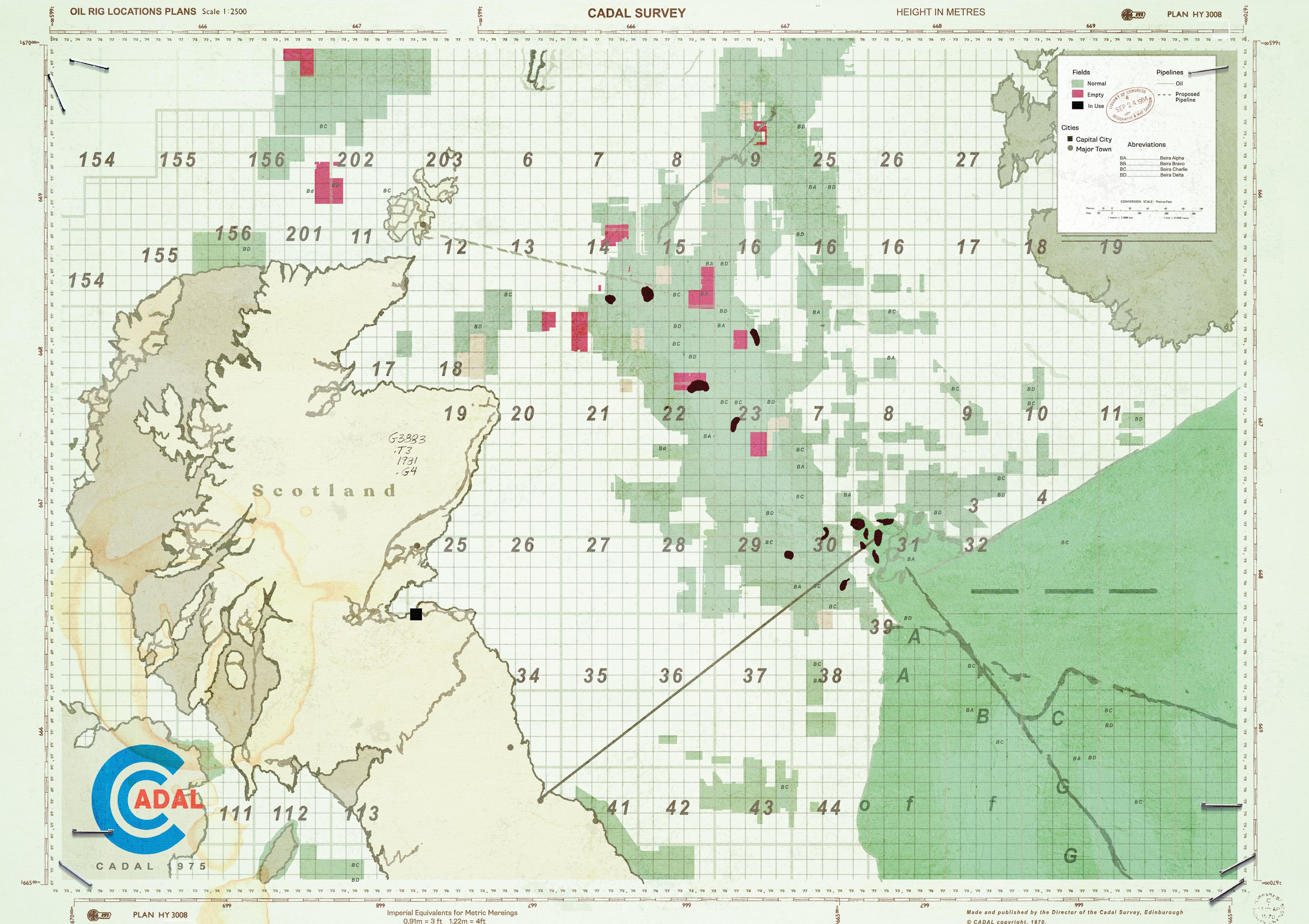

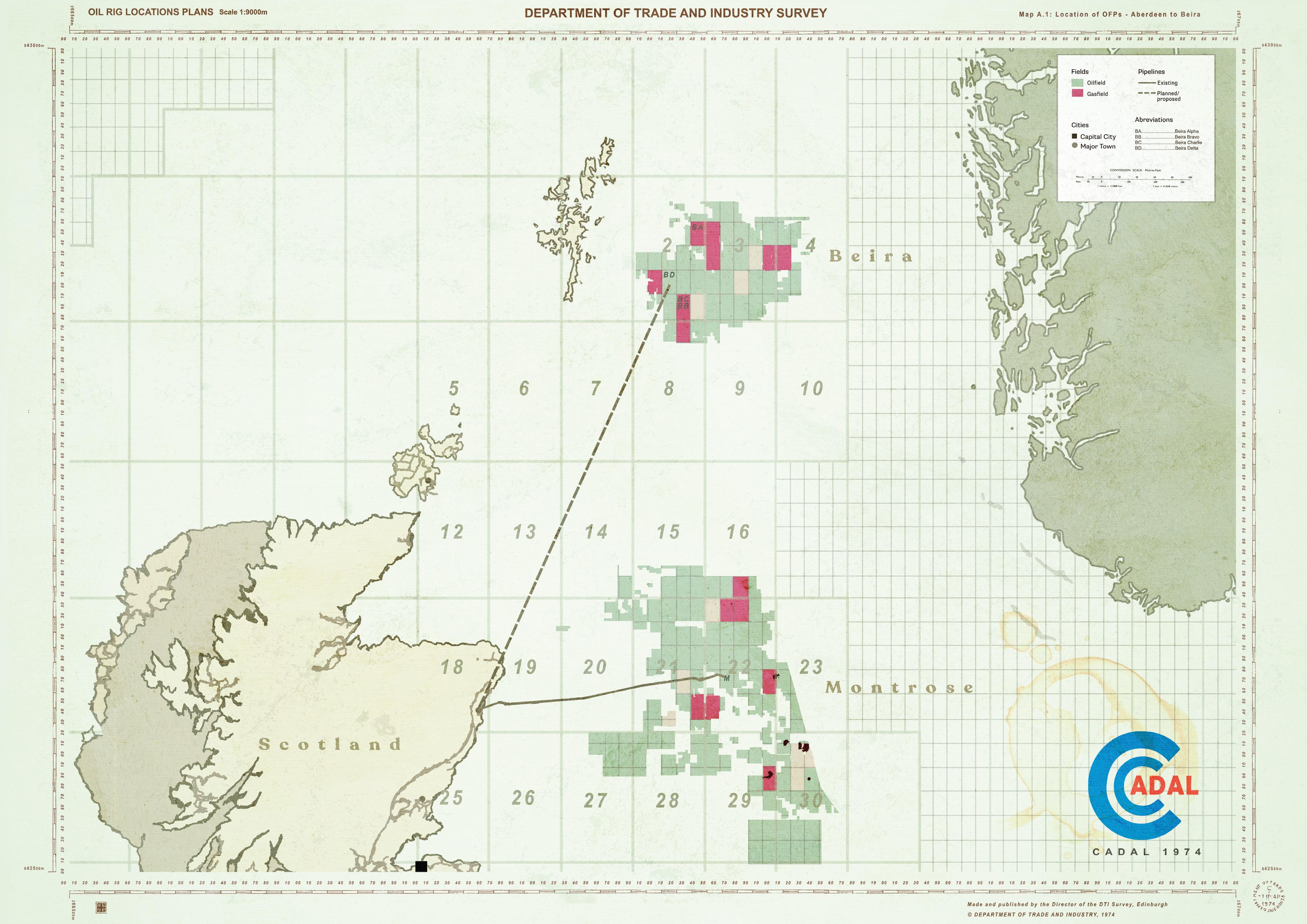

How, though, do you go about creating an oil rig that feels authentic? Did the team visit any real-world rigs? “We wanted to,” McLachlan says, “and it was perfect timing because one of the real-life rig types that really fitted what we wanted to do were the Brent oilfield rigs, and they actually brought in the Brent platforms for decommissioning. They took them to Hartlepool, brought them up on shore and then sliced them up and scrapped them. It would have been amazing to go there, but it was COVID, and it was really just impossible to set up a visit, what with the health-and-safety aspect layered on top of the social distancing aspect.”

But even if the team had been able to visit a real-life rig, there’s the problem that modern oil platforms barely resemble those from the 1970s. “If you look at the rigs from that time, they’re completely different to the current ones that are so much more hi-tech,” senior game designer Jade Jacson says. Instead, the team had to rely on intensive research, delving through archive footage and photographs of oil rigs from the 1970s. “The amount of research was crazy in the sense that I feel you can take any member of the team, drop them on an oil rig, and they’ll be able to tell you where the toilets are,” project creative director John McCormack jokes.

The video archive maintained by oil company BP was particularly informative and surprisingly extensive, associate art director Laura Dodds notes. “With the explosion of North Sea exploration in the ‘70s, there was actually quite a lot of documentary film footage,” she says. “It was

amazingly detailed. We went through and took so many screenshots, and just put them on this big mood board. And we were unpicking all kinds of things — like, next to the cabin beds is a reading light with a plastic casing that has this kind of bobbly texture on it. And then we were Googling, trying to find what that light fitting was, and what kind of colour that light would have made. Just drilling down into as many details as possible.” (Pun very much intended.)

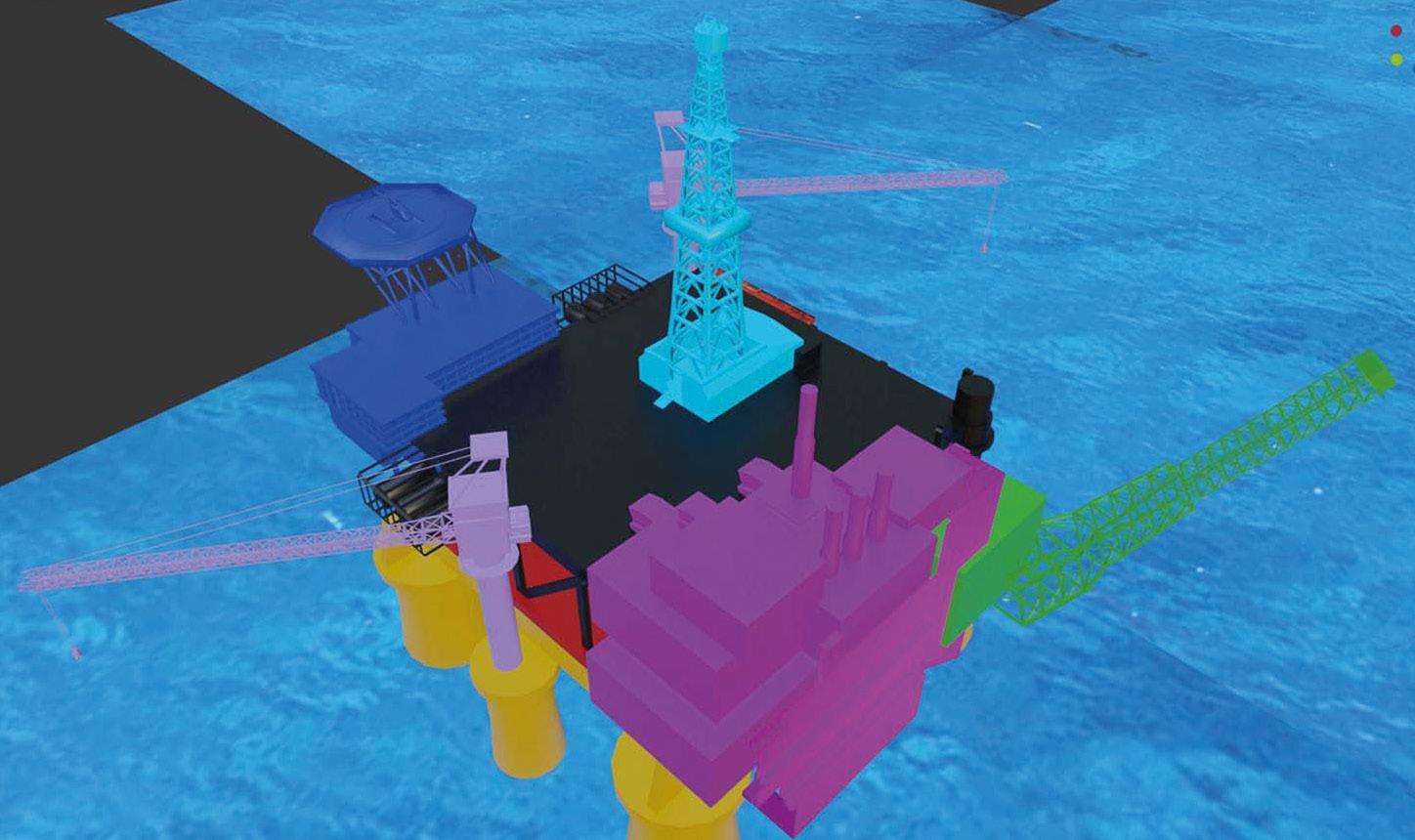

But the team’s attempt to map out the various areas of an oil rig quickly revealed a gap in their understanding. “First of all, it was hard to find out what some of these spaces were called: one of the big challenges was actually just getting the terminology [right],” says Dodds. “Once you started getting all the lexicon, then you knew what to search for to find out what the function of the space was. Then we were just looking for loads of interesting spaces for the blockout [the rough 3D layout], like the pump room, interior spaces, spaces high up on the rig, domestic spaces, engineering spaces, and trying to get a feel for the scale of those.”

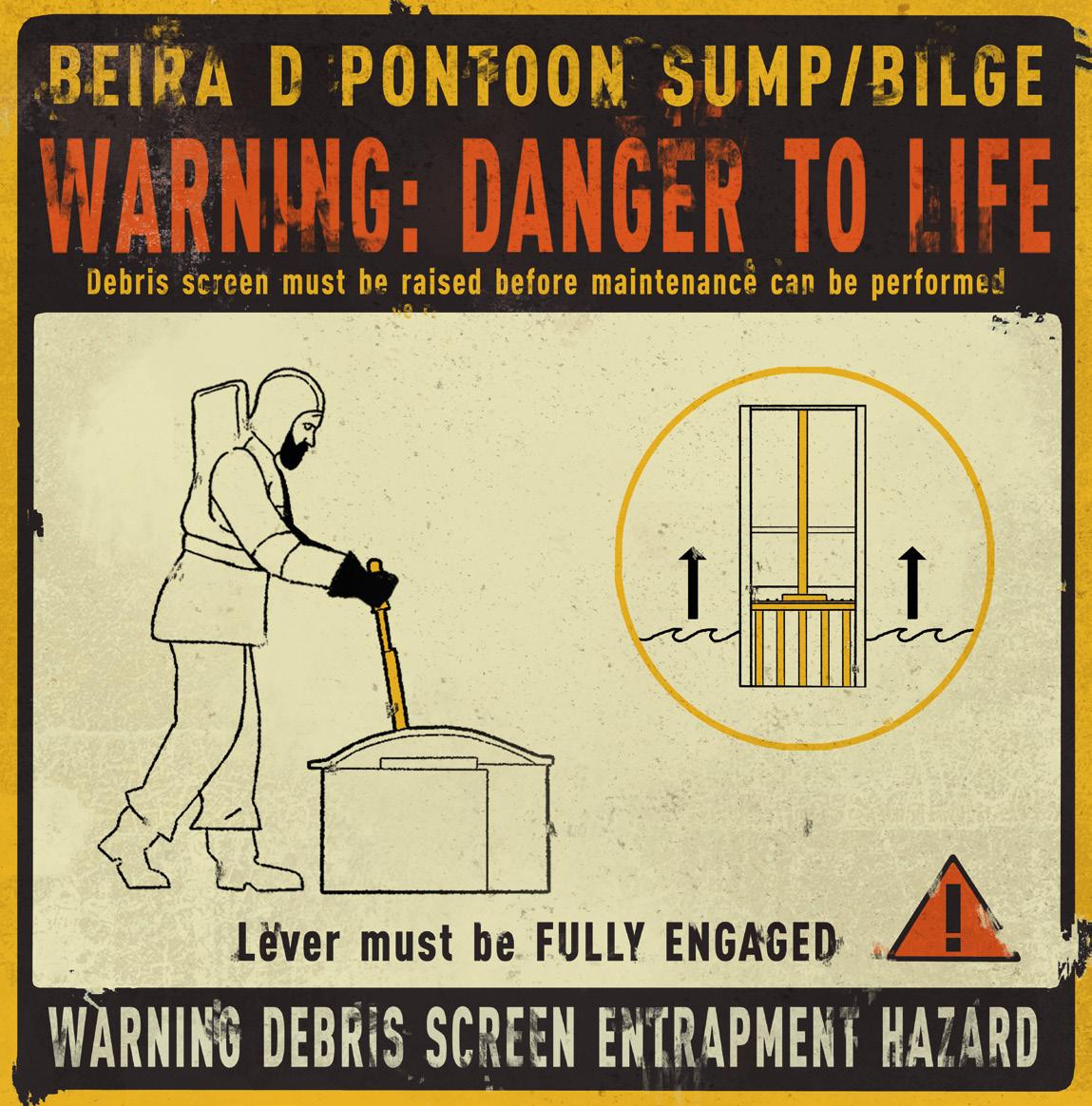

The Chinese Room also interviewed someone who had actually worked on a North Sea oil rig in the 1970s: the fatherin-law of a friend of audio director Daan Hendriks. Dodds remembers him providing one particular insight into 1970s work culture that had a significant effect on how the studio approached environmental design. “There was less health and safety than I thought, because we actually did want to do quite a bit of signage and bring the environment to life with some safety posters, but he said there was really barely anything back in the day,” she says. “It was a dangerous frontier, it really was,” McLachlan adds. The interview also yielded numerous small details that helped to make the game feel more true to life. “We were asking all sorts of questions about

what it felt like to live there,” Dodds says.

“Because you don’t quite get that personal feeling from the documentaries.”

BIGGER IS BETTER

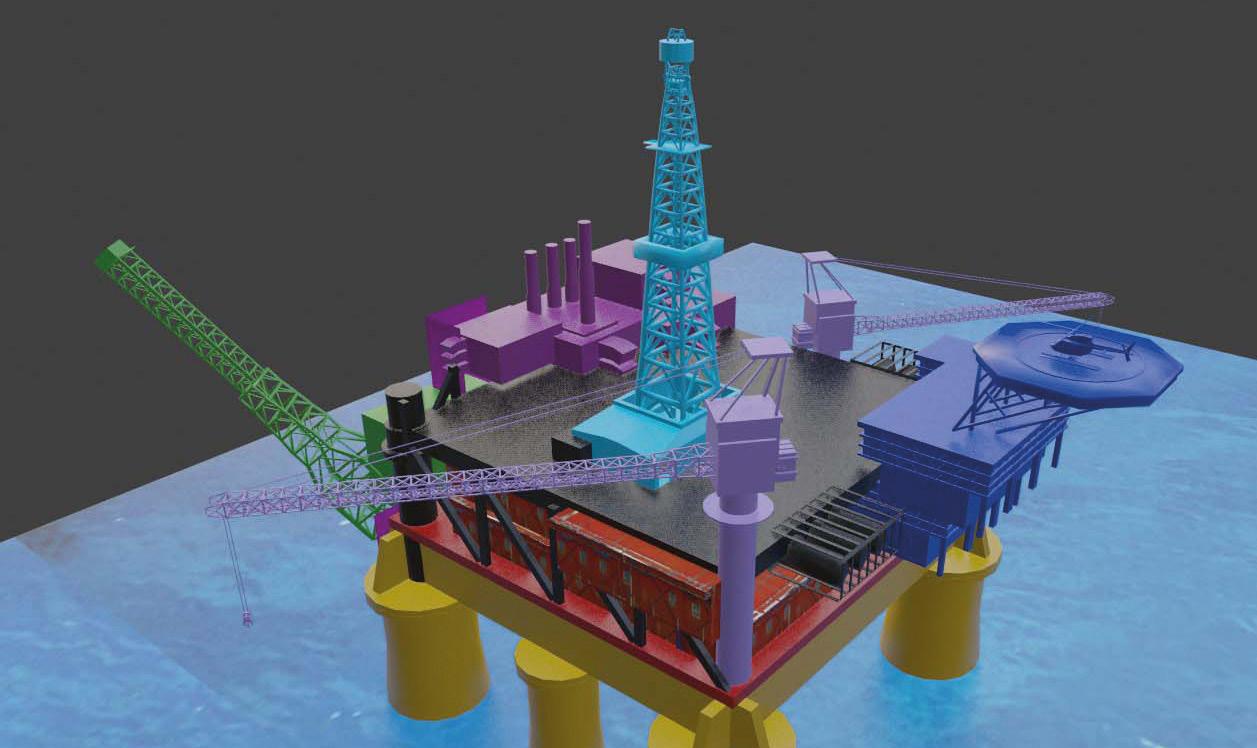

Although the team had committed to creating an authentic 1970s oil rig, there was one aspect where they used some artistic licence: the Beira D is actually a lot larger than a typical 1970s oil platform would have been. The decision to make it bigger partly came about because of the way a first-person camera shrinks spaces, McLachlan explains — a corridor with truly authentic dimensions would feel incredibly narrow in 3D. But the decision also came down to making a space that fit the feeling of the story, he adds — “so that you don’t go, ‘I really need to get to engineering’, and then you look down and it’s, like, 10 metres away. If you make it bigger, it’s much more challenging, and you think, ‘Oh, this could be a real mission.’” Jacson adds that the flare stack and crane in particular are much larger than they would be in real life.

Your typical oil rig is “incredibly boxy and small,” McCormack notes. “They don’t tend to have long corridors, but if you want a chase sequence, you can’t just have a spiral staircase; it’d drive you mad. So we had to stretch the truth.” Project technical director Louis Larsson-De Wet adds that The Chinese Room stretched the truth even further at some points by employing a technique affectionately named ‘TARDISing’ — “where on the outside it looks a certain size, but then when you go in, it’s actually massive [so] we can accommodate the gameplay in there,” he says. Dodds adds that they meticulously planned the layout of the rig, “but we needed the freedom to extend a corridor to make chase sequences more effective or to add an extra floor for verticality without having horrendous knock-ons to the

entire layout of the rig structure for previous or subsequent levels.”

Beefing up the dimensions of the rig was one of the things Dodds was most nervous about: she worried in particular that oil rig workers would say the game was inaccurate. “But so far, everyone has really embraced the game and said, ‘wow, they’ve really captured the feeling of being on these oil rigs — and I know, because I’ve worked on one.’”

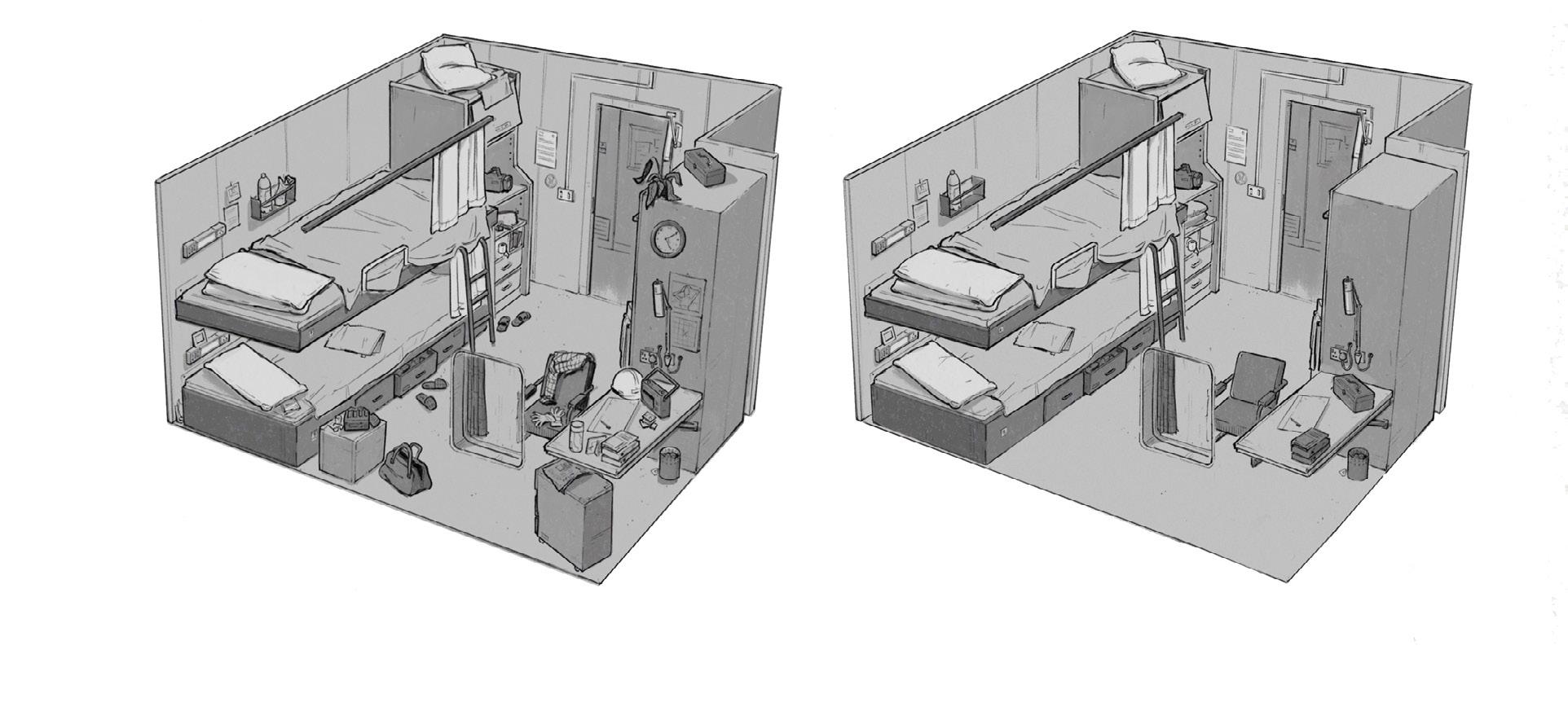

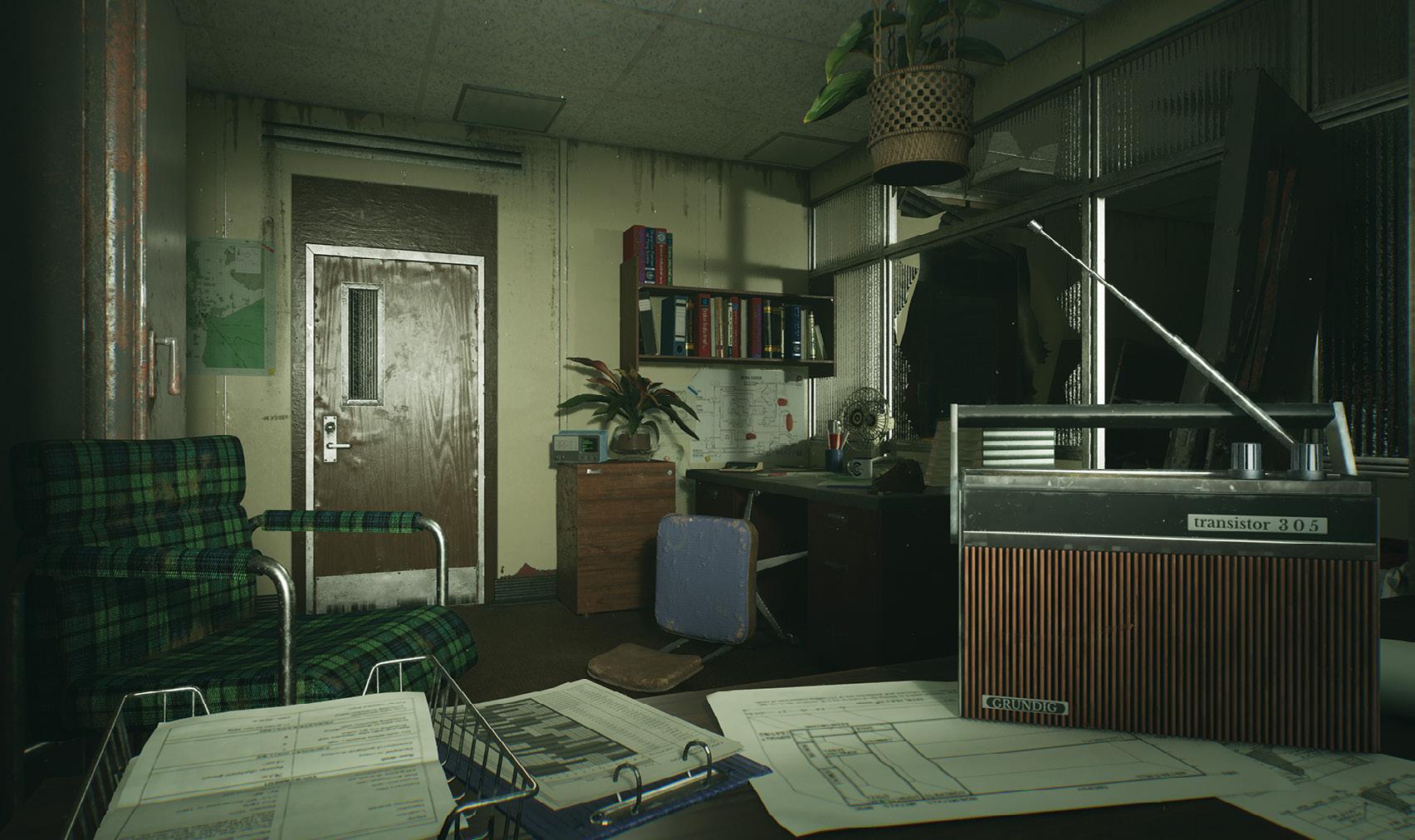

Back at the start, though, Dodds realised she knew almost nothing about what oil rigs are actually like. “I remember first hearing about the project, and if someone said oil rigs to me, I just thought it was a big metal structure,” she says. “I hadn’t really thought about the fact that people live on them. And that’s when I became really fascinated, because we started making the cabins as one of the first spaces.” The cabins evolved into one of the most memorable parts of Still Wakes the Deep each one packed with tiny details evoking the personality of its occupant.

GETTING TO KNOW YOU

Jacson recalls several meetings with senior environment artist David Vortrefflich where the two went over each of the characters and thought about what kinds of items they might own, and what their rooms might look like. “We knew, for example, that Trots was kind of communist, but also very meticulous,” she says. “We even had this idea that he was a bit OCD. So his bed is made, compared to other people who don’t do it. The fact that he’s writing a letter to ask for more things for his crew — and he even has a picture of the crew, and I think he’s the only one to have that — just shows how important it is for him.”

Unsurprisingly, the space belonging to the game’s protagonist was the first one the team worked on; indeed, it appeared

in a very early demo for the game. “We remade Caz’s cabin I don’t know how many times,” she says. “Just layers and layers of detail got put in. And when we started to expand, having more cabins that the player could explore at the beginning of the game, it actually started going much more quickly, because we knew who these characters were. I remember I made a cabin for Gibbo, and we just knew what we wanted [to include] and where [to put it].” The objects you can pick up and examine, such as the Scottish Gazette in Trots’ cabin, were added quite late, McLachlan says — late enough, indeed, that they became a problem during localisation. The plan was to include more of these objects, he adds, but there were concerns about slowing down the pacing at the start of the game, plus worries about overfilling the cabins with interactive items. One item you can interact with in the crew lounge is a handwritten note showing brackets for the darts tournament. Is it a coincidence that Brodie and Finlay meet in the final, and they’re also the two remaining characters at the end of the game? “Maybe I was thinking about that!” Dodds laughs.

She’s also particularly proud of O’Connor’s cabin, she says, “because it was completely empty, but we put this dripping in, and it’s meant to be foreshadowing.” When you meet O’Connor much later, he has become fused to a wall, and eventually drowns as the water level rises, while calling out for someone called Mary in anguish. Originally he had many more lines that called back to the constant dripping in his room — such as, ‘Mary, I think it’s raining,’ ‘There’s water everywhere, it’ll ruin the carpet,’ and ‘I’m leaking, Mary.’ “I always think about O’Connor being left alone in that huge dark pontoon with just the sound of dripping water and oil,” Dodds laments.

NUTS AND BOLTS

When you think of an oil rig, you might imagine that the legs on the bottom extend all the way to the ocean floor. In a few cases they do, where the rig is in relatively shallow water. But the team decided early on that the Beira D would be a hybrid between a submersible and a tension-leg platform, where the rig floats on massive pontoons below the water line,

but is tethered to the seafloor by thick cables. The pontoons provide some of Still Wakes the Deep’s most memorably horrid gameplay sections, as Caz negotiates these gloomy, semi-flooded spaces while being gruesomely surprised by the odd floating corpse. Initially, that level was going to be “a simple walk through the pontoons, but it evolved to be a lot more eerie and spooky,” lead environment artist Iain Gillespie says, adding that more pontoon levels were originally planned, but eventually dropped.

Jacson notes that the pontoons were particularly hard to design. “Compared to all the other places on rigs, you almost have no pictures of them,” she says. It was rare for documentaries about oil rigs to feature these dark and seldom-visited places, so McLachlan says the team had to rely on other references instead, such as ships’ holds and bilges, to get an idea of what the inside of real-life pontoons might look like. The fact that Caz can traverse the pontoons, though, is an authentic detail: “We found some line drawings of early tension-leg platforms showing there was a way that people could walk through them,” McLachlan says.

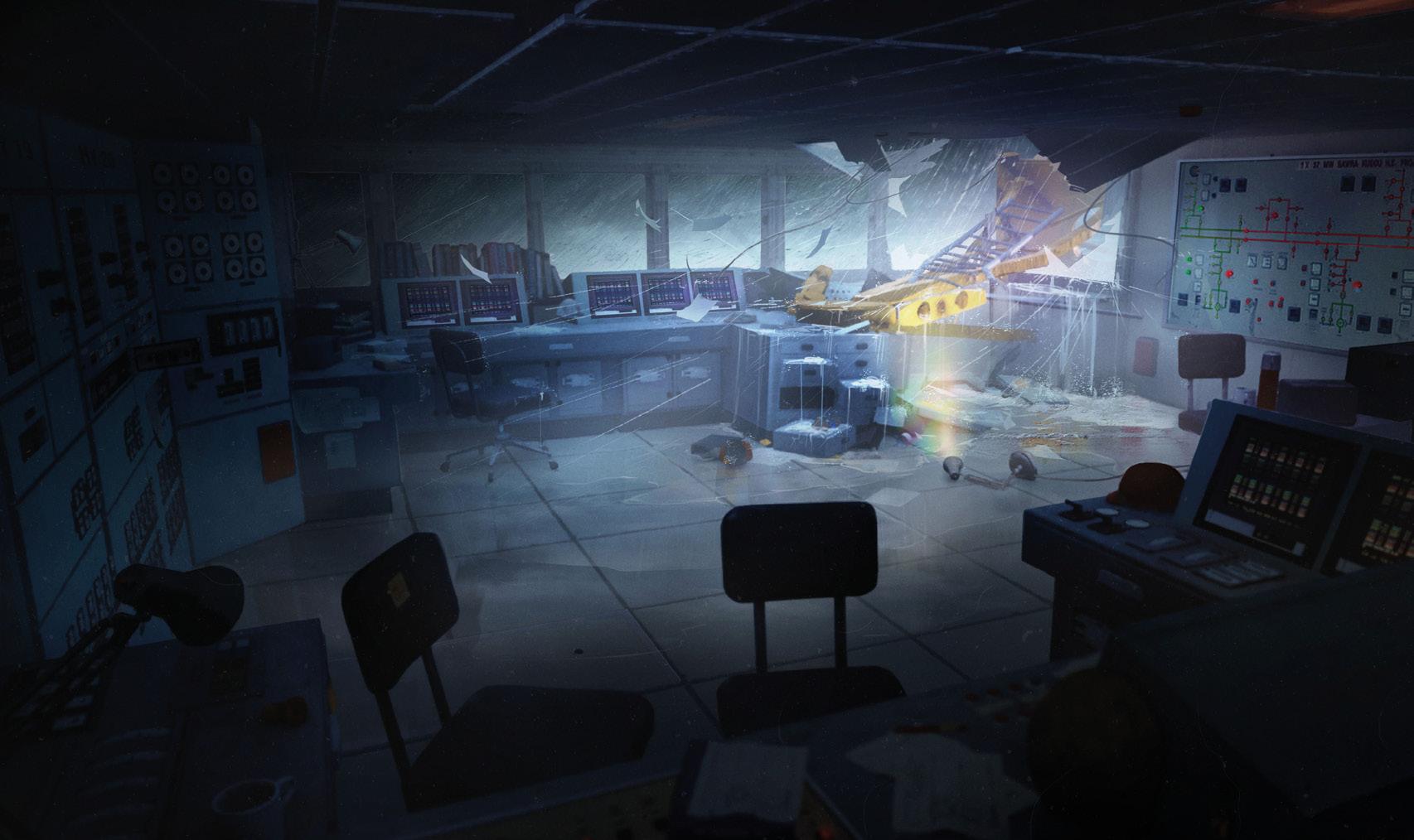

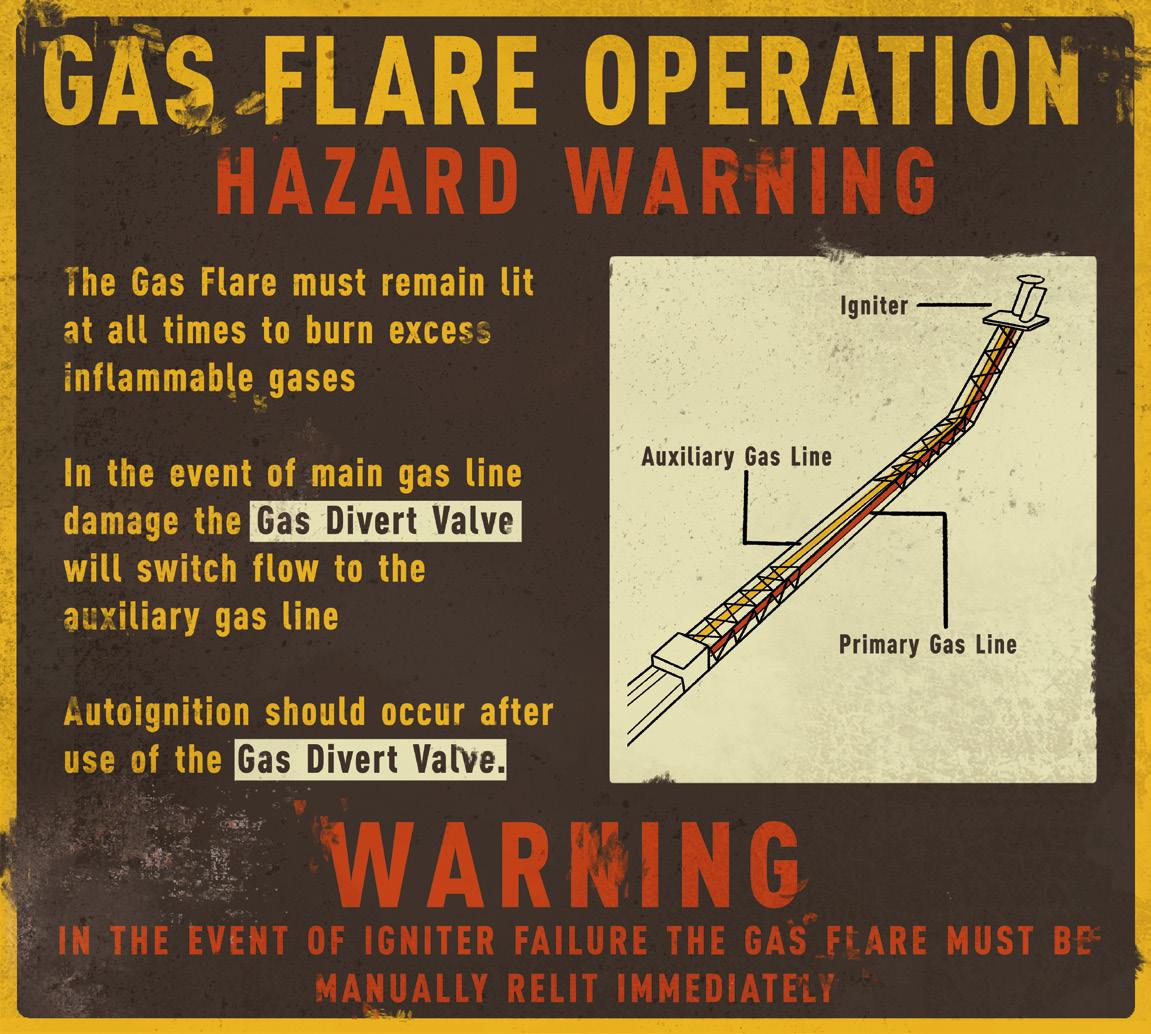

Having conducted extensive research on the machinery you would find on a real-life oil rig, The Chinese Room subsequently began to think of ways these objects could be woven into the gameplay. Dodds remembers giving environment artist Gabriela Woch an open brief of trying to find equipment on a 1970s rig that would be fun to interact with. “She managed to pull it off really well,” Dodds says. “It all started because we had this big engine in our environment, in the space where you’re being chased by Addair, and we didn’t originally have an interaction with that. And we all felt like we really wanted to get our hands on some of this machinery and have the oil rig fantasy.”

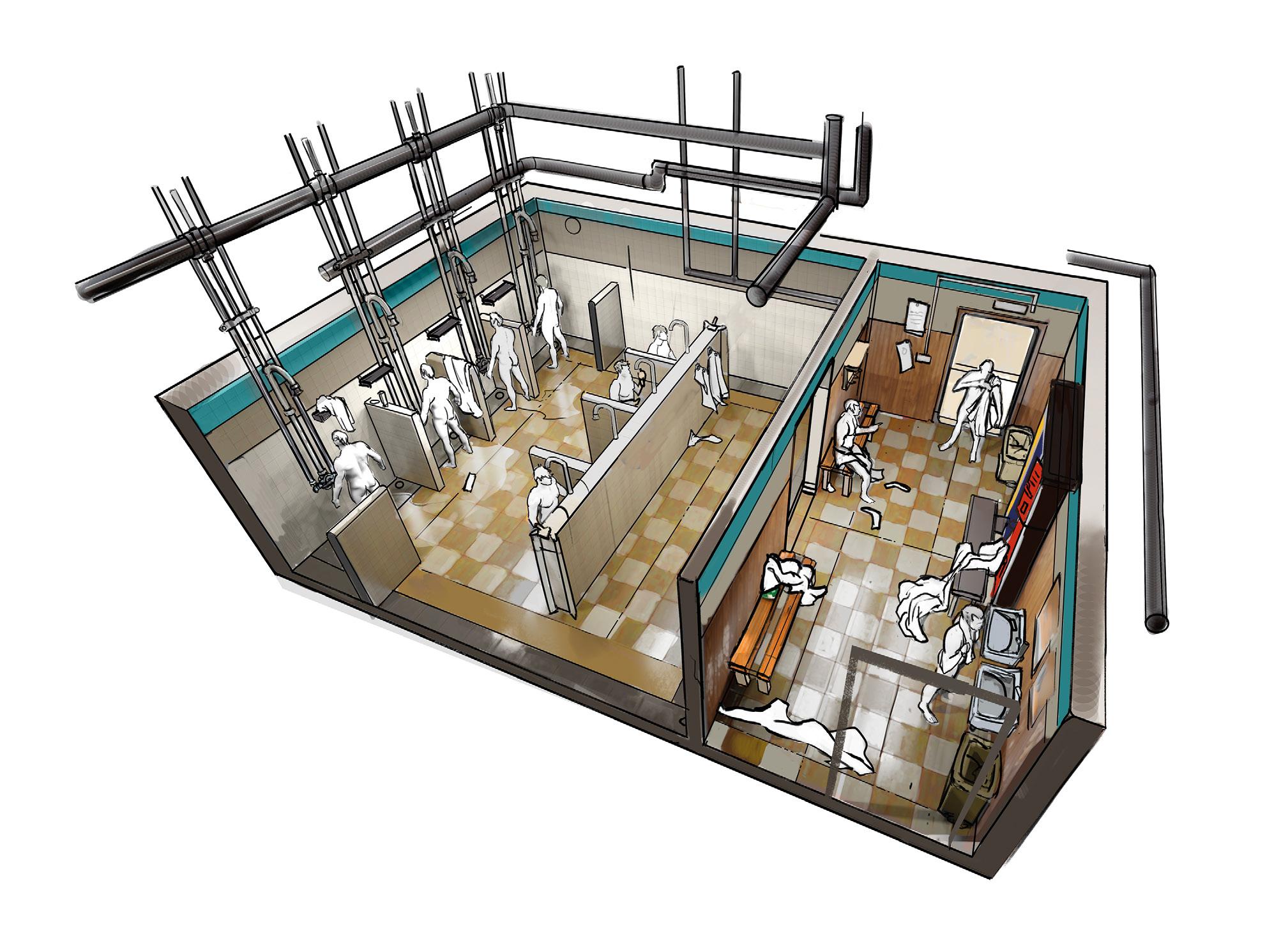

A sketch of the shower cubicles, one of the first locations you pass through in the game’s opening sequence. Only one person is showering here in the final game.

were plans to animate and add VFX, but in the end the quiet machines without power helped build up to the creepy confrontation with Addair.

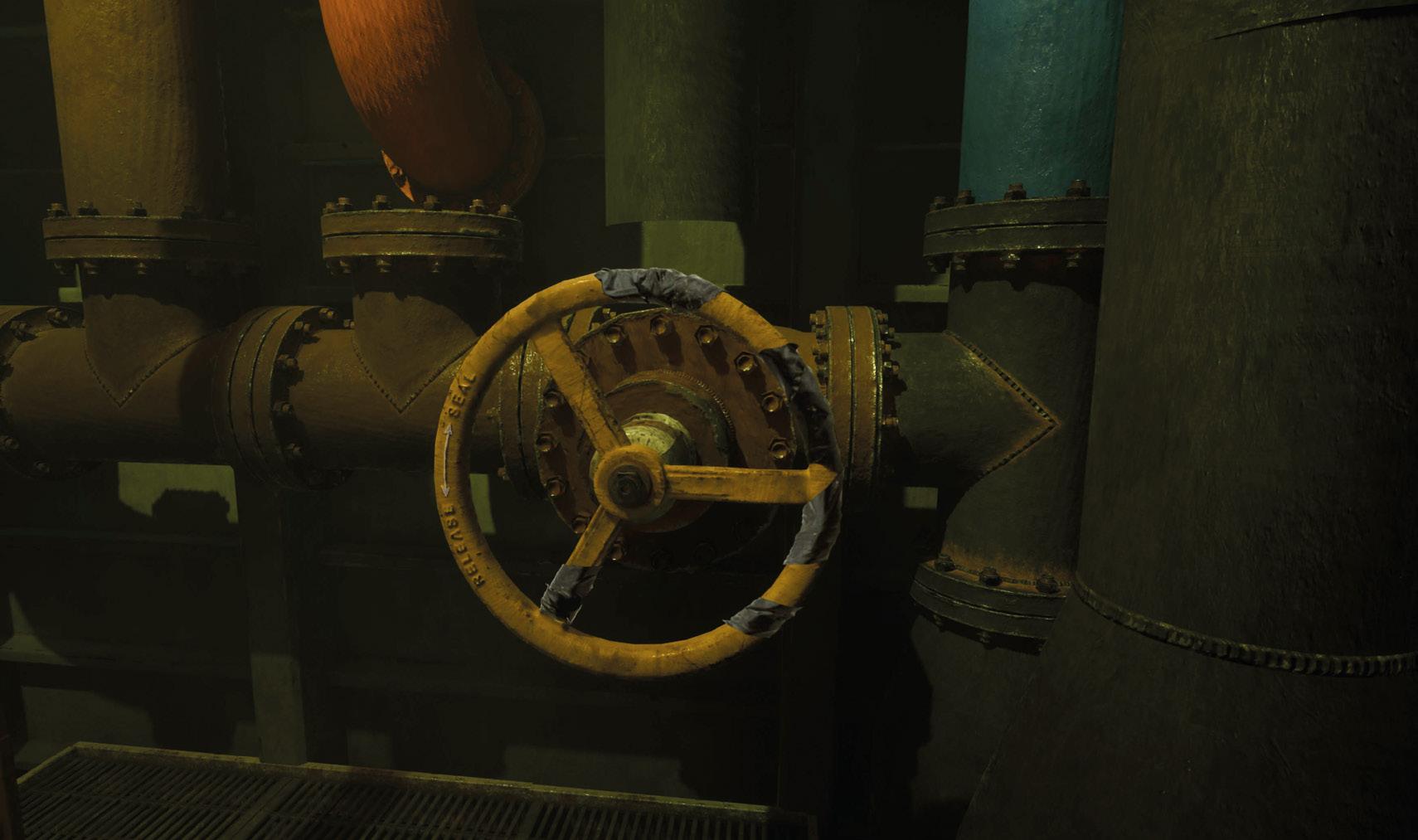

The game’s many levers are designed to be deliberately chunky and tactile. The overall goal of these concepts was to cement the visual language for all of the game’s interactable objects.

Caz has to turn off several gas and steam valves throughout Still Wakes the Deep

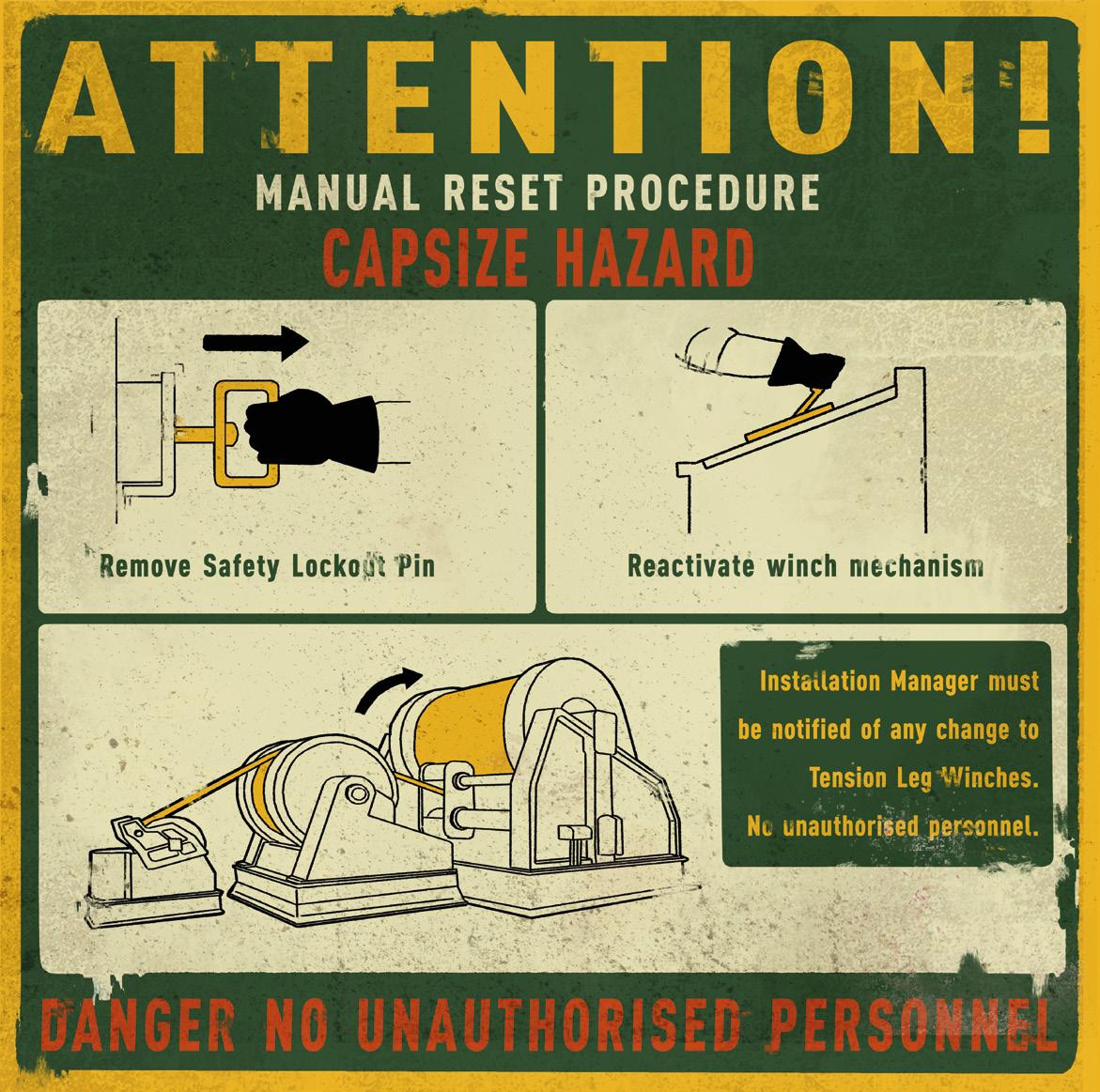

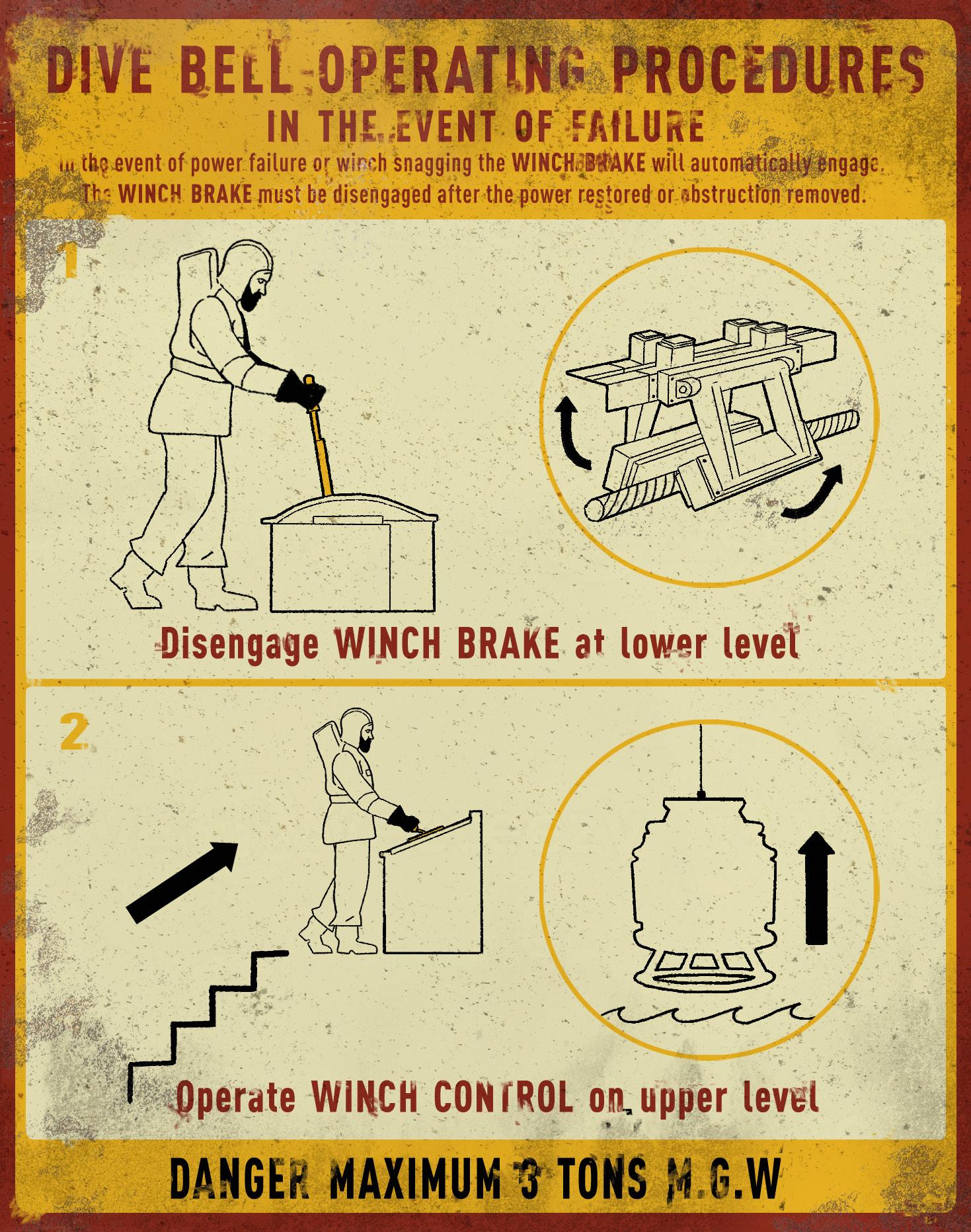

Yellow is used to highlight moving parts in the instruction posters.

A warning poster from the pontoons sequence.

Caz has to manually relight the flare stack at one point.

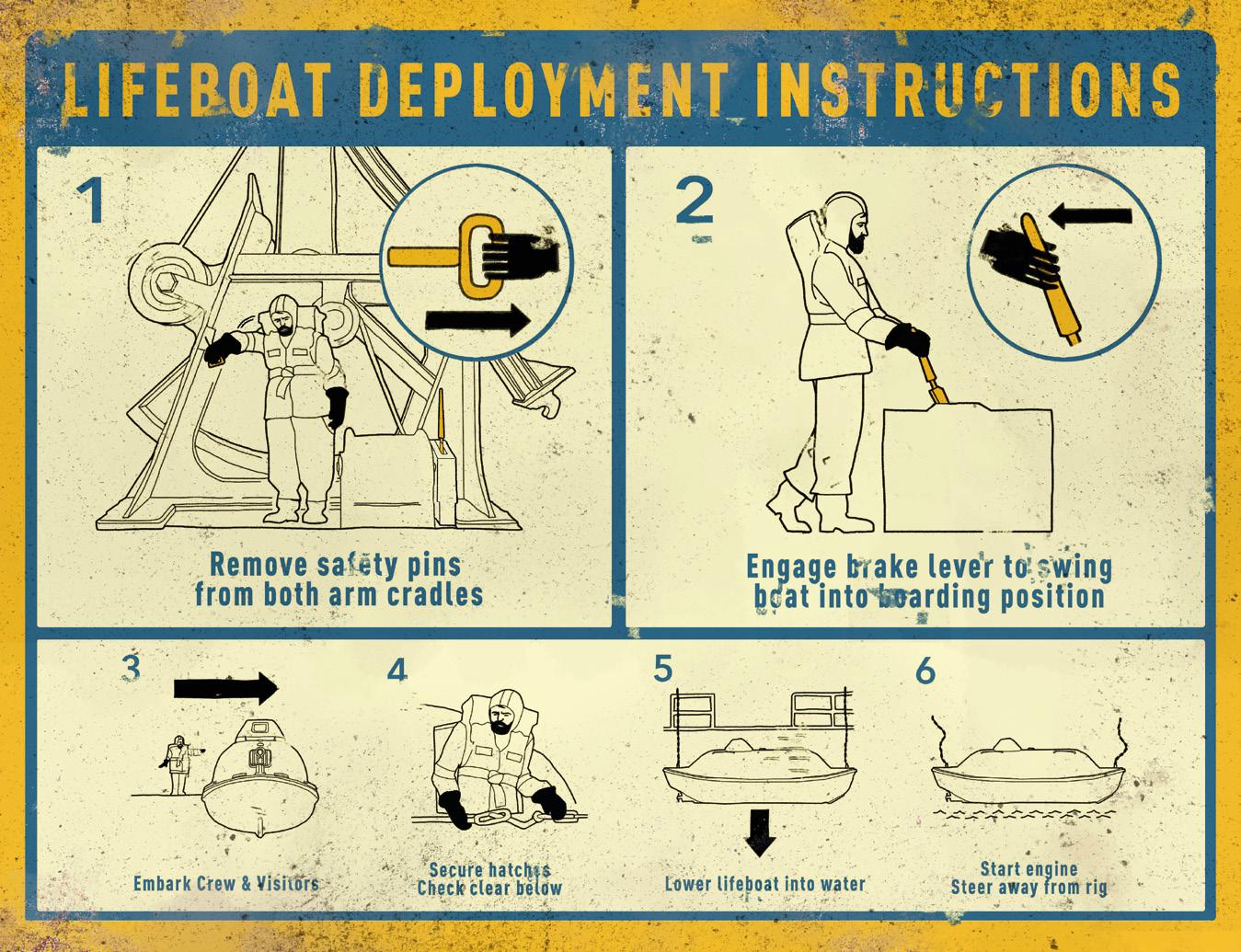

Instructions for the deployment of the lifeboat. The team researched various lifeboat lowering mechanisms and went with the one that felt the most tactile.

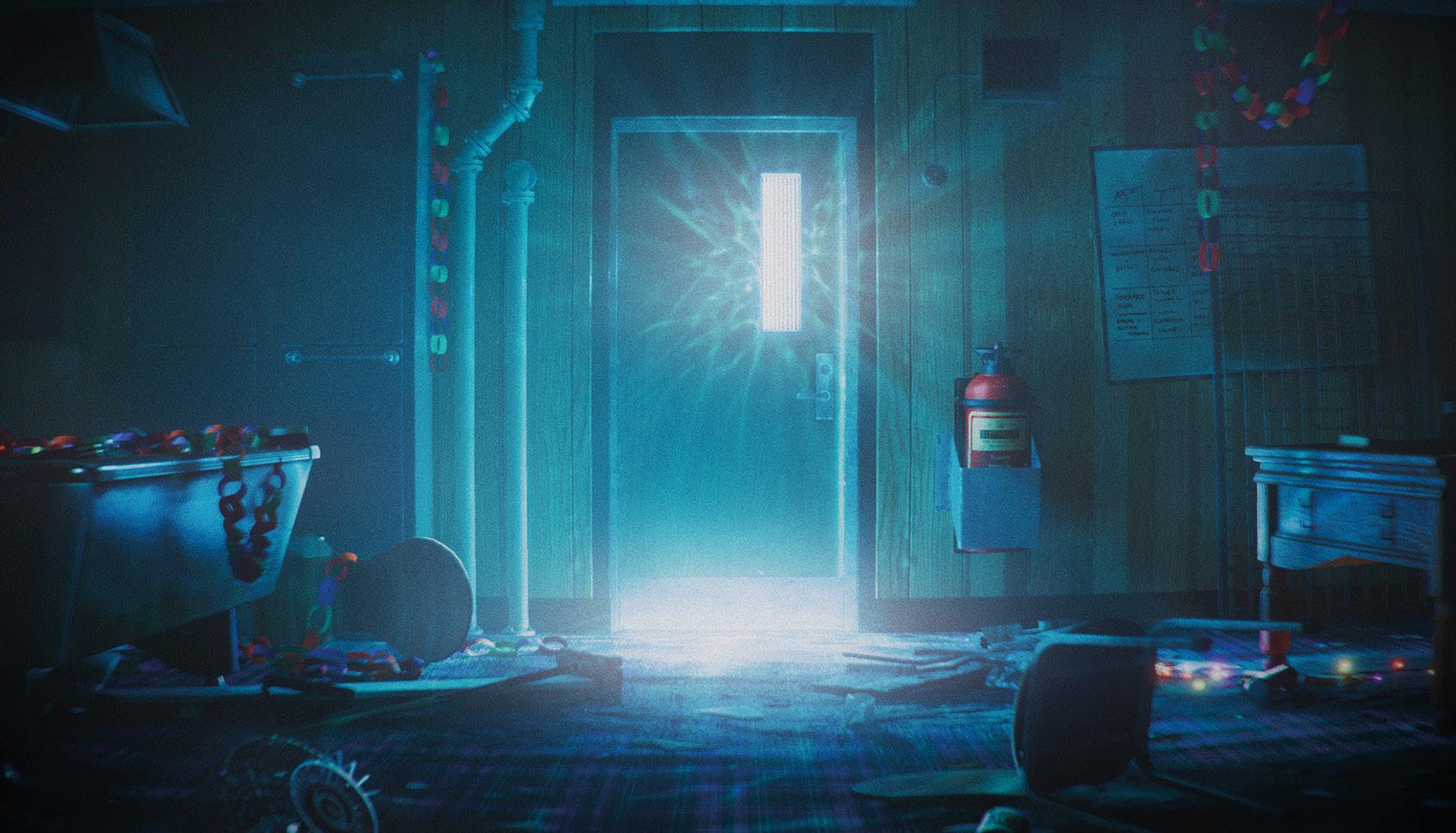

The eerie blue light here, in a scene where Trots transforms behind a locked door, is somewhat reminiscent of the movie poster for The Thing

Paintover of the pump room, showing interior pipes. On a real rig, pipes are colour coded according to what they contain: blue typically signifies cold water.