June 2023

Actualizing Internet for

All: Exploring Federal Solutions to the Digital Divide

Jasmine Lewis, John R. Lewis Social Justice Fellow

Jasmine Lewis, John R. Lewis Social Justice Fellow

Overview

Today, despite the growing importance of reliable high-speed internet access, or “broadband,” a substantial number of communities across the nation—namely lowincome, elderly, urban, rural, and tribal communities—do not have adequate access to the internet. In fact, as of 2021, more than 42 million Americans did not have the ability to purchase broadband internet.1

This policy brief examines several key policies within the Internet for All Initiative established by the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act (IIJA) that aim to bridge the digital divide in the United States. It concludes by making recommendations for maximizing the efficiency, effectiveness, and longevity of the current available programs.

Exploring the Digital Divide and Its Implications

The economic, educational, and social inequalities between those who have the ability to fully access, utilize, and benefit from digital technologies and those who do not is referred to as the “digital divide.” The term emerged in the 1990s as mass internet access increased dramatically due to a surge in the ownership of personal computers and the development of internet browsers. While the term originally referred to the divide between those who had physical access to computers, it has expanded to include factors such as internet access and digital literacy skills.2 Although the digital divide has existed for decades, the COVID-19 pandemic illuminated its discriminatory effects. Internet access rapidly became a vital resource for participation in daily life, and the shift toward remote work, e-learning, and other virtual activities left individuals and households without reliable high-speed internet vulnerable, both economically and academically.

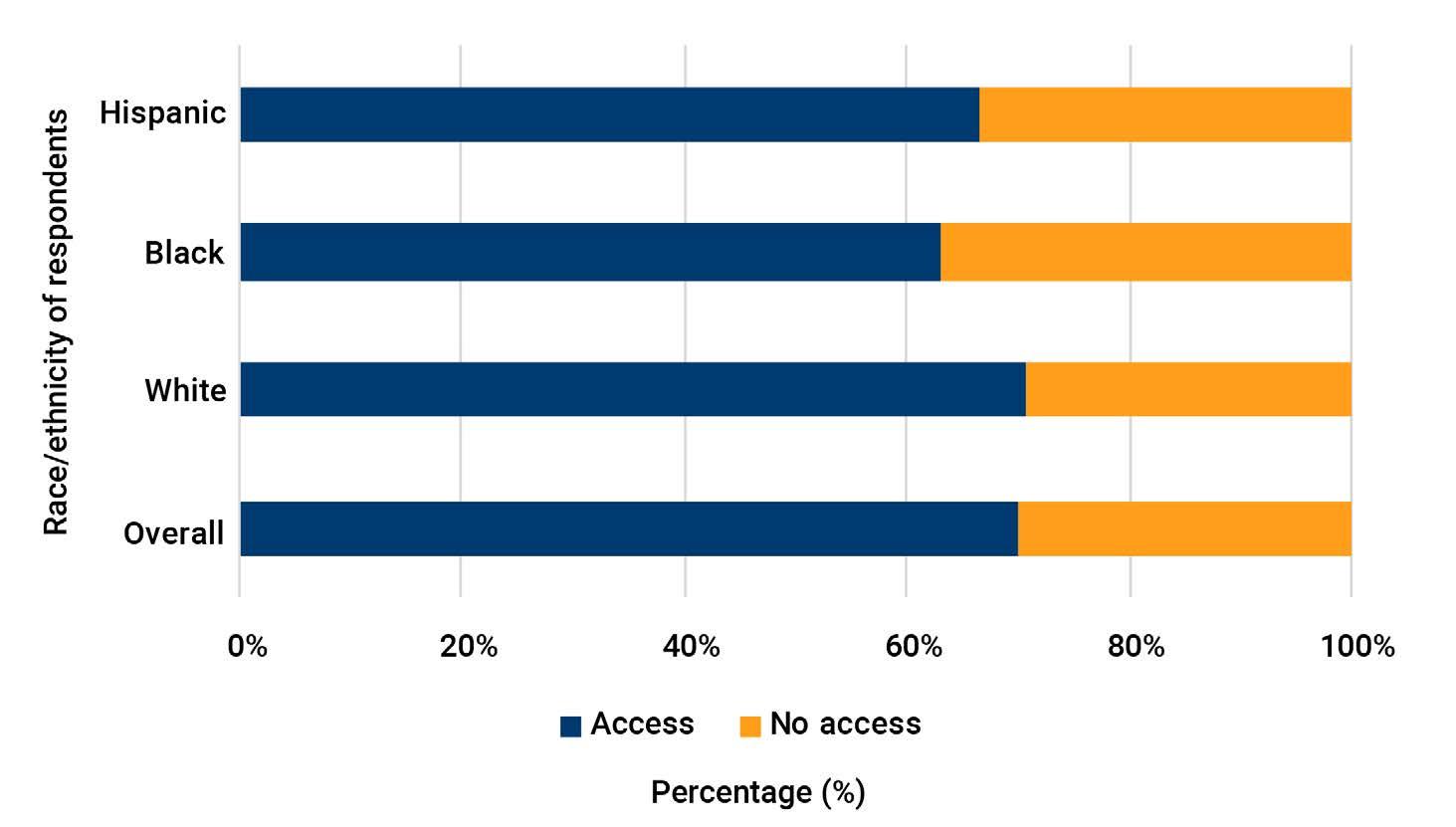

Minorities, in particular, have been disproportionately impacted by the digital divide. The Black population in the United States consistently has the lowest rates of broadband access. Approximately 40% of Black American households do not have high-speed internet. In urban cities, the Black population is twice as likely as their white counterparts to lack high-speed broadband. In the rural South, 38% of Black households lack broadband compared to 23% of white households in the same region.3 And while a larger share of rural households lack broadband, nearly three times as many households without broadband are in urban areas.4

WEIGHTED RESPONDENTS ACCESS TO HIGH-SPEED BROADLAND BY RACE

Workforce: The World Economic Forum predicts that by 2030, 90% of jobs will require digital skills.5 Those without internet access and the opportunity to increase their digital literacy skills risk being left behind. More recent studies have found that 17% of Black Americans had no digital skills, while 33% had limited digital skills.6 Digital skills deficiency impacts the kinds of jobs that one may presently attain, as well as in the future. Additionally, those who lack reliable broadband access earn less than those with access. In fact, access to reliable broadband increases the average income of low-income individuals by more than $2,000 per year.7 In the absence of adequate broadband, workers face less access to telework opportunities, job postings, and online applications. An increase in reliable high-speed broadband in Black communities would aid in reducing the racial wealth gap by creating more opportunities for economic mobility.

Education: As schools across the U.S. engage in remote learning, students with limited access to the internet continue to be at risk of suffering significant learning loss.8 Without the internet access necessary for online learning, students may face difficulties accessing online instruction and completing schoolwork and homework alike. Equipping students and their households with reliable internet service is a crucial step toward closing the educational attainment gap between students of color and their white counterparts.

Health: Inadequate broadband access also has significant implications for health outcomes in the Black community. For example, communities with insufficient broadband connectivity are excluded from the benefits of telehealth services. This is particularly

troublesome in low-income communities with higher rates of chronic disease, as well as rural communities with fewer health care providers.9 Patients that lack broadband equipped with the bandwidth to support live, synchronous audio-visual telehealth visits, have unequal access to services such as preventive care, prescription refills, and routine chronic illness visits.10 Further, internet access is critical for obtaining essential public health information such as patient-provider communications and other public medical and health information.11 Bridging the digital divide is critical to achieving racial health equity.

BARRIERS TO CONNECTIVITY: AVAILABILITY AND AFFORDABILITY

The two major causes of the digital divide are broadband availability and broadband affordability . Rural communities often experience broadband availability because they lack the infrastructure necessary for reliable, high-speed internet connection. Lack of broadband availability in Black communities, particularly in the rural south, is often due to a practice called digital redlining. Digital redlining occurs when internet service providers (ISPs) deliberately and systematically exclude low-income neighborhoods from the use of digital technologies by underinvesting in broadband infrastructure and services. The practice of digital redlining even extends to an ISP’s provision of inferior services, including unaffordable prices and slow internet speeds.12 Unserved rural communities that do not experience digital redlining are sparsely populated and/or geographically hard to reach and are therefore excluded from broadband infrastructure due to the high costs of reaching them and the low returns on investment.13

In contrast, for urban areas, the primary barrier is broadband affordability. Although broadband infrastructure may exist and be available, the costs associated with accessing internet services are often unaffordable.14 Indeed, costs are the primary barrier to broadband access for lowincome households. The average cost of broadband in the United States ranges from $50-$70 per month. These high prices often leave Americans with tough decisions about whether their incomes should go toward staying connected or toward other essential services.

What is the Internet for All Initiative?

The Internet for All Initiative was established by a provision in the Infrastructure, Investment & Jobs Act of 2021 (IIJA). It invests $45 billion to provide affordable, reliable high-speed internet for everyone in America by 2030. The programs included in the Internet for All Initiative are administered and implemented by the National Telecommunications and Information Administration (NTIA), the Federal Communications Commission (FCC), the Department of Treasury, and the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA).

Internet for All Initiative Programs

1. Affordable Connectivity Program (ACP)

The Affordable Connectivity Program provides a discount of up to $30 per month toward internet service for eligible households and up to $75 per month for qualifying households on Tribal Lands. It also provides eligible households with $100 toward paying for devices such as laptops, desktop computers, or tablets.

2. Broadband Equity, Access, and Deployment (BEAD) Program

The BEAD Program provides $42.45 billion to fund planning, construction of broadband infrastructure, mapping, and adoption programs in all 50 states, Washington D.C., Puerto Rico, the U.S. Virgin Islands, Guam, American Samoa, and the Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands. It prioritizes locations that are unserved and underserved.

3. Broadband Infrastructure Program

The Broadband Infrastructure Program provides $288 million to build partnerships between states and internet service providers to expand internet access to unserved areas, particularly in rural communities.

4. Capital Projects Fund

The Capital Projects Fund provides $10 billion in funding to support capital projects that help rural, tribal, and low-income communities deliver vital online services such as telehealth, education, and work.

5. Connecting Minority Communities Pilot Program

The Connecting Minority Communities Pilot Program provides $268 million in grants to Historically Black Colleges and Universities (HBCUs), Tribal Colleges and Universities (TCUs), and Minority-Serving Institutions (MSIs). The grants go toward helping organizations purchase broadband internet service and equipment, as well as hiring and training information technology personnel.

6. Digital Equity Act

The Digital Equity Act provides $2.75 billion for the purpose of establishing three grant programs that promote digital equity and inclusion. The three programs include two state formula programs and one competitive grant program.

7. Enabling Middle Mile Broadband Infrastructure Program

The Enabling Middle Mile Broadband Infrastructure Program is a $1 billion program that expands and extends middle mile infrastructure, thereby reducing the cost to serve unserved and underserved areas. Middle mile infrastructure refers to the mid-section of internet infrastructure that carries large amounts of data at high speeds over long distances.

8. ReConnect Loan and Grant Program

The ReConnect Loan and Grant Program expands high-speed internet service to rural areas by providing nearly $2 billion in loans and grants. The funding may be used to pay for construction, improvements, and the acquisition of facilities and equipment for infrastructure projects.

9. State Digital Equity Planning Grant Program

The State Digital Equity Planning Grant Program supports community programs to help scale digital literacy. These programs are intended to give vulnerable individuals the necessary skills to effectively use the internet.

10. Tribal Broadband Connectivity Program

The Tribal Broadband Connectivity Program provides $3 billion to tribal governments for the deployment of broadband internet to tribal lands, as well as for telehealth, distance learning, affordability, and digital inclusion.15

Spotlight: The Affordable Connectivity Program (ACP) and the Broadband, Equity, Access and Deployment (BEAD) Programs

The ACP and BEAD programs offer the greatest opportunities for expanded broadband access, particularly for Black communities. While the ACP makes internet service more affordable, BEAD funding allows for significant investments in broadband infrastructure, particularly in rural communities with large Black populations.

AFFORDABLE CONNECTIVITY PROGRAM (ACP)

With unprecedented funding and seventeen million households enrolled in the ACP already, it is the nation’s largest-ever broadband affordability program. In May 2021, the COVID-19 relief package created the Emergency Broadband Benefit Program (EBB), a temporary program established to help Americans afford internet service during the pandemic.16 In December 2021, the ACP officially replaced the EBB as a longer-term extension of the emergency program. A 2022 study found that only 25% of eligible households have enrolled in the program.17 In response to low uptake, the Biden-Harris Administration announced more than $73 million in grants to increase awareness and enrollment in the ACP.

BROADBAND, EQUITY, ACCESS AND DEPLOYMENT (BEAD) PROGRAM

The BEAD Program provides each state and territory funding to support broadband deployment, mapping, capacity-building, and other adoption projects. Additional funding will be targeted toward unserved and high-cost locations across states, based on broadband maps produced by the FCC. In March 2020, the Broadband Deployment Accuracy and Technological Availability Act (DATA Act) was enacted, which mandated that the FCC collect precise information about broadband availability throughout the country in order to update national broadband maps. All BEAD funding allocations will be based on the FCC’s new broadband maps by distributing funds based on the number of unserved locations in each state.18 Because the maps fundamentally determine how much additional funding each state is allotted, the accuracy of the data is key to adequately funding the states with the greatest need for additional resources. To ensure the greatest accuracy of the maps, the FCC implemented a challenge process that allows consumers, governmental entities, and other parties to dispute the availability of mobile broadband service, as well as the availability of fixed broadband service at a particular location.19 The map is designed to be adjusted biannually to reflect the collection and integration of new data collected by the challenge process.

5 Ways the Internet for All Initiative Impacts the Black Community

1. Increases Long-Term Broadband Accessibility

The digital divide is felt most acutely in the rural South, where Black Americans make up nearly half of the region’s population. Due to digital redlining and the prohibitive costs of building out broadband infrastructure, many communities in the region suffer from a lack of broadband availability. Programs such as BEAD, the ReConnect Loan and Grant Program, and the Broadband Infrastructure Program fund broadband infrastructure projects, thus ensuring that millions of Black households have access to broadband services.

2. Increases Broadband Affordability

A significant barrier to broadband access is the unaffordability of obtaining services. In fact, most Black households who are directly impacted by the digital divide live in areas with available broadband infrastructure, but they simply cannot afford it. The ACP provides discounts on internet service, therefore significantly reducing the number of Black households who struggle with affordability. Additionally, the Connecting Minority Communities Pilot Program has enabled a number of HBCUs to purchase internet service, thereby allowing their students to access more reliable, high-speed internet.

3. Increases Racial Equity in Workforce, Education, and Health

Inadequate broadband access has negative impacts on job searches, online education, and health services. Internet For All programs that fund broadband accessibility and affordability efforts will enable Black Americans to participate in critical day-to-day activities more fully.

4. Increases Digital Skills

Insufficient digital skills have significant effects on employability as the skills that jobs require become increasingly digital. Internet For All programs that fund broadband accessibility and affordability play a fundamental role in allowing individuals to gain digital skills. Furthermore, Internet for All programs that fund digital literacy programs, such as the State Digital Planning Grant Program and the Tribal Broadband Connectivity Program ensure that those without the necessary skills have access to learning opportunities.

5. Increases Participation in Online Civic Engagement Activities

As government services become digitized, internet access is a vital tool for accessing constituent services and public benefits. Further, the COVID-19 pandemic introduced remote legal proceedings and other public forums, allowing those with high-speed internet to attend court proceedings, online therapy sessions, and counseling meetings. Internet for All programs work to provide the internet access necessary to engage in these activities, which will lead to increased racial equity in terms of access to civic engagement.

Recommendations & Next Steps

CONTINUE FUNDING THE AFFORDABLE CONNECTIVITY PROGRAM

The Affordable Connectivity Program was funded by a one-time sum of $14.2 billion. Conservative estimates predict that funding for the program will be depleted by March of 2025,20 while others predict that the funds may be exhausted by as early as November of 2024.21 Considering the $73 million that the Biden-Harris Administration released to increase outreach and enrollment efforts, Congress must act soon to continue funding the ACP.

ADVOCATE FOR ANCHOR INSTITUTIONS TO BE CATEGORIZED AS SERVICEABLE LOCATIONS

Those who struggle with reliable high-speed internet at home often rely on public spaces such as libraries, coffee shops, cafés, and schools for internet connection. However, most of these institutions have been deemed community anchor institutions (CAIs) by the FCC. Because CAIs typically subscribe to commercial broadband services rather than massmarket broadband, the FCC categorizes them as non-broadband serviceable locations.22

The implications of not designating CAIs on the maps as serviceable locations is that they are not eligible through the BEAD program, and therefore may not benefit from more

Federal Solutions

Divide reliable, higher speed internet services. Consumers and lawmakers alike should advocate for CAIs to be categorized as serviceable locations on the national broadband map, to ensure eligibility for future federal funding opportunities.

ENGAGE WITH THE FCC TASK FORCE TO PREVENT DIGITAL DISCRIMINATION

In 2022, FCC Chairwoman Jessica Rosenworcel announced the creation of a crossagency Task Force to Prevent Digital Discrimination. The task force serves to combat digital discrimination and promote equal access to broadband by developing model policies and best practices for state and local governments. Through a series of listening sessions and rulemaking proceedings open for public comment, the task force will receive feedback from affected communities and households to be used in formulating rules to facilitate equal access to broadband. Local communities that suffer from issues of broadband accessibility and/or broadband affordability should engage with the task force by requesting a meeting or submitting public comments.

Conclusion

Internet access is no longer a luxury, but a critical tool for full participation in today’s society. Black Americans, however, have and continue to trail behind in terms of access. The digital racial gap is both a symptom and a cause of social inequalities. Due to socioeconomic factors and geographical restrictions, many Black households simply do not have access to reliable, high-speed internet. In turn, these same households cannot adequately engage in essential day-to-day activities, such as online learning, remote work, and other important digital opportunities. The COVID-19 pandemic highlighted and deepened the inequalities experienced by those without access to high-quality internet services. In response, President Biden signed the bipartisan Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act (IIJA), which committed $45 billion to providing affordable, reliable, high-speed internet for all Americans by the year 2030. Named the Internet for All Initiative, it created ten distinct programs that work to build broadband infrastructure, teach digital skills, and make broadband more affordable. The Internet for All Initiative provides an unprecedented opportunity to close the digital divide—the implications of which would drastically improve economic, academic, and health outcomes of the Black community.

References

1 Busby, J., Cooper, T., & Tanberk, J. (2021). Broadbandnow estimates availability for all 50 states; confirms that more than 42 million americans do not have access to broadband. BroadbandNow.

https://broadbandnow.com/research/fcc-broadband-overreporting-by-state

2 Hartnett, M. (2019, August). Digital divides. Oxford Bibliographies.

https://www.oxfordbibliographies.com/display/document/obo-9780199756810/obo-9780199756810-0222.xml

3 Darko, A., Hinton, D., Horrigan, J., Levin, B., Modi, K., & Wintner, T. (2023, January). How to close the digital divide in Black America | McKinsey. McKinsey & Company. https://www.mckinsey.com/industries/public-and-social-sector/our-insights/ closing-the-digital-divide-in-black-america

4 Campbell, S., Ruiz Castro, J., & Wessel, D. (2021, August 18). The benefits and costs of broadband expansion. Brookings.

https://www.brookings.edu/blog/up-front/2021/08/18/the-benefits-and-costs-of-broadband-expansion/

5 Guo, J., & van Eerd, R. (2020, January 17). Jobs will be very different in 10 years. Here’s how to prepare. World Economic Forum. https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2020/01/future-of-work/

6 Bergson-Shilcock, A. (2020, April 21). Applying a racial equity lens to digital literacy. National Skills Coalition. https://nationalskillscoalition.org/resource/publications/applying-a-racial-equity-lens-to-digital-literacy/

7 Lelkes, Y., Ticona, J., & Yang, T. (2021). Policing the digital divide: Institutional gate-keeping & criminalizing digital inclusion. Journal of Communication, 71.

8 Hoskins, H. (2022, March). Unplugged: Examining COVID-19 and its Technological Impact on Black Students. Issuu; Congressional Black Caucus Foundation. https://issuu.com/congressionalblackcaucusfoundation/docs/f_2022_1

9 Adetosoye, F., Hinton, D., Shenai, G., & Thayumanavan, E. (2023, March 16). Telehealth: Closing the digital divide to expand access | McKinsey. https://www.mckinsey.com/industries/public-and-social-sector/our-insights/virtual-health-for-allclosing-the-digital-divide-to-expand-access

10 Bailey, V. (2021, August 6). Limited Broadband Poses a Significant Barrier to Telehealth Access. MHealthIntelligence. https://mhealthintelligence.com/news/limited-broadband-poses-a-significant-barrier-to-telehealth-access

11 Lustria, M. L. A., Smith, S. A., & Hinnant, C. C. (2011). Exploring digital divides: An examination of eHealth technology use in health information seeking, communication and personal health information management in the USA. Health Informatics Journal, 17(3), 224–243. https://doi.org/10.1177/1460458211414843

12 Pickard, V., & Popiel, P. (2022, August). Against digital redlining: Lessons from philadelphia’s digital connectivity efforts during the pandemic. Benton Foundation. https://www.benton.org/blog/against-digital-redlining-lessons-philadelphiadigital-connectivity-efforts-during-pandemic

13 Campbell, S., Ruiz Castro, J., & Wessel, D. (2021, August 18). The benefits and costs of broadband expansion. Brookings. https://www.brookings.edu/blog/up-front/2021/08/18/the-benefits-and-costs-of-broadband-expansion/

14 Office of Minority Broadband Initiatives 2022 Report (p. 42). (2022). National Telecommunications and Information Administration. https://broadbandusa.ntia.doc.gov/sites/default/files/2022-11/DOC_NTIA_OMBI_Congressional_Report.pdf

15 Programs | internet for all. (2022). https://www.internet4all.gov/programs

16 Leanza, C., & Wein, O. (2021). How a new federal program is helping more people get connected to broadband. The Leadership Conference on Civil and Human Rights. https://civilrights.org/blog/how-a-new-federal-program-is-helpingmore-people-get-connected-to-broadband/

CPAR | Actualizing Internet for All: Exploring Federal Solutions to the Digital Divide

17 EducationSuperHighway. (2022, October). Accelerating Affordable Connectivity Program Adoption. https://www. educationsuperhighway.org/no-home-left-offline/acp-data/

18 Rachfal, C. L., & Zhu, L. (2022). FCC’s National Broadband Map: Implications for Broadband Equity, Access, and Deployment (BEAD) Program (p. 3). Congressional Research Service. https://crsreports.congress.gov/product/pdf/IF/ IF1229819

20 Kane, J. (2022). Congress should prioritize the affordable connectivity program for broadband funding. https://itif.org/ publications/2022/09/23/congress-should-prioritize-the-affordable-connectivity-program-for-broadband-funding/

21 Marcattilio, R. (2022, May 19). The Fate of the Affordable Connectivity Program. Community Networks. https:// communitynets.org/content/fate-affordable-connectivity-program

22 Howell-Brown, Z. (2022, November 29). Fcc maps inaccurate on anchor institutions, spacex requests licensing, new consolidated cfo. Broadband Breakfast.

https://broadbandbreakfast.com/2022/11/fcc-maps-inaccurate-on-anchor-institutions-spacex-requests-licensing-newconsolidated-cfo/

CENTER FOR POLICY ANALYSIS AND RESEARCH

Economic Opportunity

For more research visit cbcfinc.org