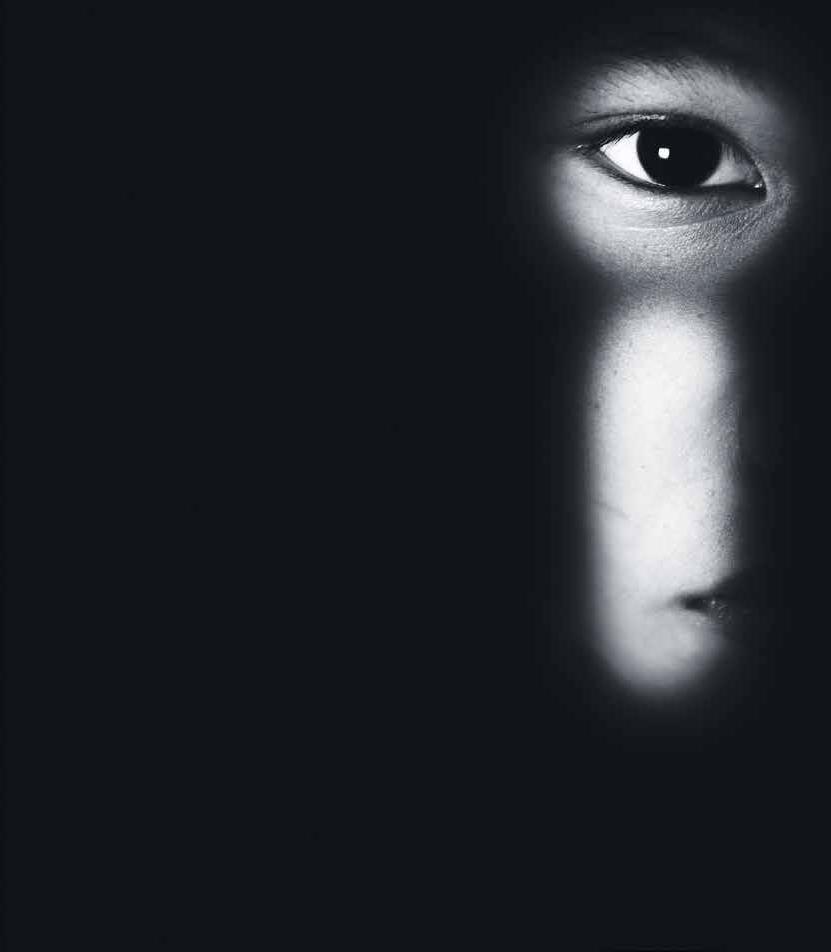

COVID19 SPECIAL REPORT: MENTAL HEALTH

AUSTRALIA’S MENTAL MELTDOWN

ALMOST OVERNIGHT, THE CORONAVIRUS CAUSED UPHEAVAL TO OUR DAILY LIVES. AS PEOPLE BEGAN TO FEEL IMPRISONED IN THEIR OWN HOMES, THE MENTAL HEALTH OF MANY BEGAN TO FRAY. CHRISTOPHER KELLY REPORTS.

S

ome of us were better able to cope at self-isolating than others. If you were a homebody before the lockdown, someone perfectly comfortable in their own company, chances are you adapted fine. If, however, you’re normally a social butterfly, flitting from pillar to post, you wouldn’t have responded as well to having your wings clipped. Australians were not alone in their self-isolation. In April, half of the world’s population had their movements curtailed to some degree or another. Tens of millions of lives changed beyond the realm of normalcy. As well as the confinement, people have had to cope with financial insecurity, family separation, and feelings of bereavement. To cap it all, we’ve had legitimate health fears to endure. In March, crisis support and suicide prevention service, Lifeline, recorded the highest volume of calls the organisation has ever had to deal with in a single month — 90,000, or one every 30 seconds. By Easter, the COVID lockdown had caused widespread mental meltdown. According to Lifeline CEO Brent McCracken, Good Friday was “the biggest day” in the organisation’s 57-year history. Speaking to reporters, McCracken said: “We saw people struggling with loneliness, and the isolation, exacerbating the circumstances they’re in.” When asked who was reaching out to the support service, he simply answered “everybody” — “[People] losing their business, losing their job, finding themselves without other people around them, having a lack of

18

social contact,” he said. “Many are facing circumstances they could never have envisaged they would be in. Many are feeling their life is becoming worthless.” While a lot of the callers to Lifeline included people with chronic mental health issues aggravated by the crisis, the numbers also included a new category: people who’d never reached out for mental health support before. Meanwhile, data from Kids Helpline showed that an Australian child was calling the counselling service every 69 seconds. “They are worrying about and struggling with the impact this is having on their daily lives — whether that is school or university closing, not being able to do team sport or go to the gym, travel and holiday, as well as not being able to see their friends or boyfriend or girlfriend,” said Kids Helpline CEO Tracy Adams. To help people cope with the COVID crisis, mental health non-profit, Beyond Blue, launched a 24/7 Coronavirus Mental Wellbeing Support Service. Beyond Blue CEO Georgie Harman said the move was in response to the organisation recording a 30 percent spike in contacts since the crisis began — on some days, as many as one in three calls were COVID-related. “People are telling us they’re feeling overwhelmed, worried, lonely, concerned about their physical health and the health of friends and loved ones, and anxious about money, job security and the economy,” said Harman. During the lockdown, researchers at Monash University launched a study to better understand COVID-19’s impact

Inner Sydney Voice • Winter 2020 • www.innersydneyvoice.org.au

on Australians’ mental health. When surveying 1,200 people about how they were coping during the crisis, results showed that most participants recorded mild levels of anxiety and depression, while 30 percent registered moderate to high levels. “In normal times,” said senior research fellow, Caroline Gurvich, “the majority of people fall in the normal range, so we are seeing elevated levels of depression and anxiety.” A YouGov poll conducted over Easter found more than half of Australians (57 percent) were feeling stress because of the COVID crisis. More than three-quarters of respondents (77 percent) said they were anxious about not being able to see their families; 71 percent were unhappy about not being able to hang out with friends; while 60 percent were worried about financial insecurity. Professor Ian Hickie is Co-Director of the Brain and Mind Centre at the University of Sydney. Appearing on a university podcast — Sydney Ideas — Hickie said the coronavirus had threatened two of the “fundamental pillars of mental health”. “One’s personal autonomy. Being in control of your life by knowing what the risks are and taking appropriate actions to minimise the risk. The other is social connection. Humans are social animals. If we have strong social connection, we thrive.” Both pillars came swiftly tumbling down when the coronavirus reached Australian shores. For mental health expert, Professor Jane Fisher, the overriding theme during the COVID lockdown was one