8 minute read

Student Profiles

Alan Plotz ‘21, far left, with his fellow Supermarket Drive planners in 2019 (Kim Hoang ‘21, Elise Requadt ‘19, Anirudh Nistala ‘21, Lawrence Wang ‘21)

Alan Plotz ‘21: Mobilizing for Change

Advertisement

At recess, Alan Plotz regularly sets the standard for Bill Wharton’s “concise and essential” announcements: “Politics Club will meet in 3E to talk about the impeachment hearings. A lot of people are interested in where the attacks on Vindman are coming from, so we’ll discuss that along with Trump’s legal strategy and the precedents for it.” Or: “Next week I’m going to the GBRSAC meeting [Greater Boston Regional Student Advisory Committee, to which Alan’s classmates elected him as a representative]. Let me know about topics you think I should bring to the group, or if you’d like to know what we’ve been working on.”

These offer only a glimpse of Alan’s vast array of activities. Through his work with United 4 Social Change, he has been writing a curriculum to train less privileged students to find paid internships, an opportunity much more readily available to those with professional parents and connections. He has also organized protests: As a ninth grader at Commonwealth, he put together a walkout after the Parkland shootings. We weren’t in session during the national walkout, but when we were back from our March break, Alan ran our own event, organizing student speeches while working with faculty to minimize disruptions to school.

Another cherished project, with Boston Mobilization, examined inequities in school discipline. Alan looked at data from numerous schools, working to clarify the relationship between disciplinary action and the race of the students involved. Through GBRSAC, he also managed to wrangle access to students’ responses to questions about school climate on the MCAS. Closer to home, he’s organized a one-day Model Congress at Commonwealth. For this, he started with the list of schools on the back of the T-shirt from Harvard’s multiday Model Congress. After many emails, Alan ended up with enough schools to run the conference, including some whose students don’t often find their way into our building.

Most recently Alan joined several of his fellow students and alumni/ae— Mosammat Faria Afreen ’16, Iman Ali ’18, Gueinah Carlie Blaise ’16, Tristan Edwards ’18, Kimberly Hoang ’21, Alexis Domonique Mitchell ’16, Ryan Phan ’22, and Tarang Saluja ’18—in petitioning the school to more closely examine the ways in which it historically has not fully supported all students of color, as well as those who are first generation and/or come from low income backgrounds. As Commonwealth, along with the rest of the country, reckoned with racism, privilege, and white supremacy in the wake of George Floyd’s murder, this group advocated for the school to address the inequities within its walls. Their petition sparked conversations bringing together the whole of Commonwealth’s community in what can only be the beginning of a much larger movement.

Whenever he talks about social-justice work, Alan’s joy is evident, but he also describes his struggle to remain aware of his own blind spots as a privileged student. Last summer, he stepped into another kind of uncomfortable position: in Tajikistan, learning the language through a State Department program. Like most Americans abroad, he came to understand his own values better as he puzzled over those of his hosts, who seemed to place the interests of their own families ahead of those of the larger community or the nation. As he played with his host family’s kids, he came to see these priorities as logical: because of their country’s recent history, it made sense to value stability above all else.

Without Internet access, Alan also had to step outside the relentless productivity of his life here. What made that worth it, for someone who loves getting things done? “Who knows,” Alan observes, “whether I’ll have the time to study abroad in college.” This longterm planning invites us to wonder what we’ll hear about Alan’s doings in five, ten, or thirty years.

Nick Fomin '20: The Two-Continent Family

Plenty of Commonwealth students speak another language at home: Mandarin, Russian, Spanish, Vietnamese. Many, sometimes to their parents’ frustration, tend to use English with their siblings. In Nick Fomin’s Brazilian family, he says firmly, “we make sure” everything is in Portuguese. The “we” includes his brother Thomas (Commonwealth ’22) but extends to a vibrant network of relatives and friends in both countries.

Anyone who has seen Nick in school on the last day before a vacation knows the joy in his face as he anticipates another visit to São Paulo, especially to his maternal cousins. “They’re not just cousins,” he says; they follow the same soccer teams, Netflix shows, and memes. The cousins know it gets under his skin when they call him a gringo, and he knows he can’t keep up with all of the culture when “there are only five Brazilian TV channels here.” At the same time, he declares cheerfully, “I’m an American.” When he talks about his family, he shifts fluidly among his father in Brazil and his mother and stepfather here, his “American cousins” on his father’s side, and others who move easily back and forth between cultures and countries.

In this web of relationships, many threads converge on the cafés his family operates: seven branches in Brazil and one here, now in Framingham. The cafés originate eight years ago, when his father, in a park in São Paulo, made a friend who became his business partner. The story of their first café includes Nick and Thomas taking two-week courses, getting up at 5:00 a.m., to learn to work as baristas. By now, Nick says, “I think every single person in my family is involved.”

Nick’s stepfather managed the café here in its first location on Newbury Street. His mother and his paternal grandmother, who love to bake, work together in the kitchen when his grandmother is here.

The more you hear about the cafés, the easier it is to understand why Nick says, “I have never felt like the child of a divorced family.” His father and mother are separated but talk all the time. He describes his grandmother as effectively an aunt, not an ex-mother-in-law, to his mother; they come from the same town in Brazil. He calls his father’s business partner “pretty much a member of the family.” Just as Nick’s cousins are also his friends, no one seems stuck in a single role. That includes Nick as an employee in the cafés. He notes that it’s more fun in São Paulo, where the pace is faster, the dishes pile up at rush times, and he has to jump in wherever he’s needed.

When he’s in Brazil, Nick says he pushes back against one prevailing idea of the culture here: that “Americans don’t get it.”

At Commonwealth, he sees his classmates as “aware of what’s going on in the world.” He doesn’t take credit, but he could, for contributing to that awareness within this community.

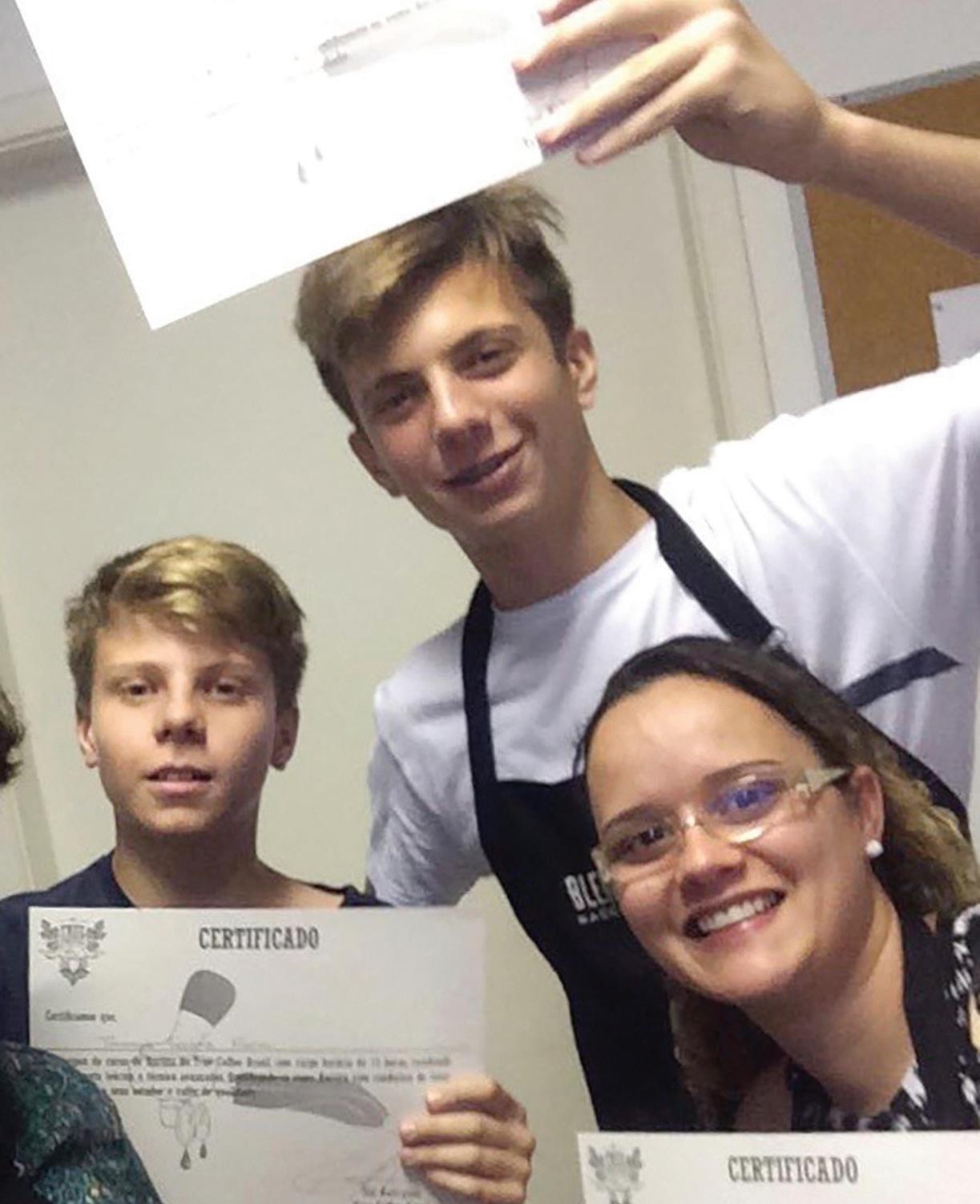

Nick Fomin ‘20 (center) and his brother Thomas (Class of 2022, left) celebrate finishing a course along with one of the other participants

When he’s in Brazil, Nick says he pushes back against one prevailing idea of the culture here: that “Americans don’t get it.” At Commonwealth, he sees his classmates as “aware of what’s going on in the world.” He doesn’t take credit, but he could, for contributing to that awareness within this community.

Ilaria Seidel ‘22: Racing and Exploring

In middle school, says this self-effacing tenth grader, “I didn’t have much of a work ethic.” By this, Ilaria Seidel means that instead of homework she threw herself into competition math and got serious about the flute, which was easier to practice during her family’s two years in New Jersey. She had played the piano since she was four, but the flute started in third grade when her father took her to a wind-quintet concert. Ilaria said she wanted to play the piccolo. “It was a joke, but the next day, my mom brought home a flute.” As the more social of the two instruments, it became her favorite. Since moving to Boston, she has played in New England Conservatory’s preparatory orchestras.

Ilaria says her life changed when she came to Commonwealth in that, rather than “really needing to find things to do” she had to start making hard choices among passionate interests. To begin with, “my eighth-grade self would never have believed I would love homework so much.” She placed into Calculus Advanced as a ninth grader but visited geometry classes for fun. This past year, she audited Creative Writing, reluctantly dropping it because “I had to find ten hours a week” when she was accepted to a research program called PRIMES. This entails working on original scholarship in a small group with a graduate-student mentor. Ilaria apologizes for not getting very far in conveying her group’s topic, enumerative combinatorics, to a curious English teacher. “It took me three weeks to understand it,” she explains.

But when she talks about PRIMES, Ilaria crisply defines a pair of categories: competition math and research math. Quoting one of her early math mentors, she describes competition math as “racing,” research math as “exploring.” To train for math competitions, students practice solving problems fast, reviewing concepts so they can apply them on the fly and drilling to build up speed. Exploring enumerative combinatorics means “you’re trying to solve a problem over a whole year, which means you’re stuck most of the time.” You have to fight through a lot of frustration, she says, and sometimes just stop and go for a walk.

The racing/exploring boundary is permeable, though. Ilaria has noticed that Commonwealth kids who loved competition math in middle school “because they were bored in math class” eagerly embrace the “exploring” our proof-based courses entail. As they progress through the curriculum, their hunger for “racing” tends to fade. Members of the math team sometimes resist using the meetings to train for competitions. Ilaria herself now takes exams like the AMC and AIME without any preparation. At the same time, she wants to keep qualifying for the next level of competition. Her goal is the Math Olympiad, with its nine hours of…proof-based problems.