10 minute read

reFlections on Wilderness

An Interview with John Fielder

By Josh Kuhn

Hallet Peak, Lake Hiayaha, Rocky mountain National park. Photo by John Fielder

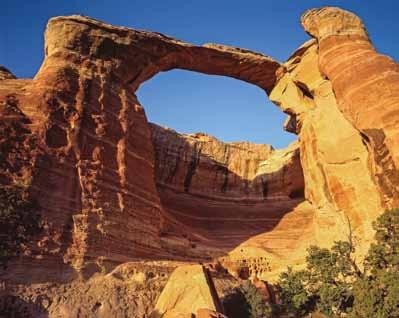

Black Ridge Canyons Wilderness. Photo by John Fielder

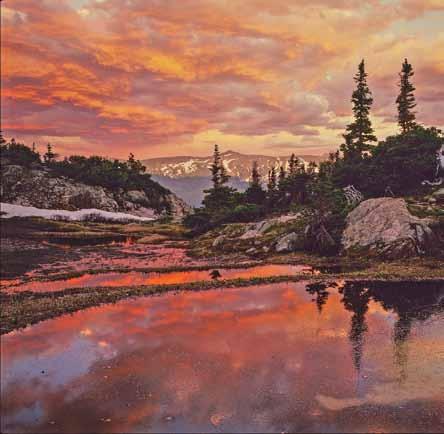

Tarns, Rocky Mountain National Park. Photo by John Fielder

During the summer between my sophomore and junior year of high school, I had the opportunity to travel out west for the first time. On this trip I explored a variety of National Forests (including several different wilderness areas), National Parks, mountains, and rivers throughout the western U.S. On the first night of this seven-week adventure, I witnessed the most amazing sunset while camping at Colorado’s Great Sand Dunes National Monument (now National Park). That night the sky looked as though it was on fire, with shades of orange that truly blew away my impressionable teenaged mind. Remarkably, I was fortunate enough to capture this special moment with my point-and-shoot camera (this was well before the digital age), and to my luck it actually came out well. For the past 17 years, I have displayed this image on various walls, bulletin boards, and refrigerators. For me this image symbolizes so many different things: memories of a wonderful summer exploring ridgelines, valleys, peaks, and rivers with a group of new friends; inspiration to continue challenging myself both physically and mentally; and the grandeur that is the western United States.

This trip served as my impetus for choosing to move out west and attend the University of Colorado. To this day, I have continued living in locations with a close proximity to wild places and have developed both a deep passion for exploring these places and an even deeper passion for ensuring they continue to remain pristine and wild for generations to come.

This past year, I have been able to work toward this passion as the CMC’s Conservation Fellow. Through this position I have been afforded the opportunity to work with land managers, diverse organizations, and dedicated volunteers in learning firsthand the challenges of managing our public lands. I was also fortunate enough to work with a Colorado legend, John Fielder, in planning a celebration to honor the 50th anniversary of the Wilderness Act. As part of this process, John shared with me his insights into photography, wilderness, and conservation. I hope you enjoy our interview, and, more importantly, I hope you get outside and enjoy our state’s extraordinary wild places.

Do you remember your first experience in Colorado’s wilderness? When and where was it, do you have any particular memories from that initial experience, and did you take any pictures?

In the summer of 1967, I was a cityslicker 17-year-old kid from Charlotte, North Carolina, with a summer job on a cattle ranch in the Wet Mountain Valley with views from the kitchen window of the Crestones in the Sangre de Cristo Mountains. My college summers were spent prospecting for non-ferrous metals for CF&I Steel Corporation in, among other places around the West, the Culebra Range of the Sangres. My first serious backpacking forays into the Sangres happened after I moved to Colorado in 1972 prior to their designation as wilderness in 1993. I had just purchased my first SLR film camera, a Canon F-1, and I wanted to see if I was the next Ansel Adams!

Have you noticed any changes in Colorado’s wilderness areas over the years? Perhaps less wildlife and more people?

A warming climate has changed the character of our forests in wilderness, especially those with lodgepole pine and spruce trees. Though I have seen the effects of spruce bud worm on coniferous forests for 40 years, its extent was relatively minor. Since the drought year of 2002, millions of acres of pine forests have died by infestation of pine bark beetle in Colorado, and a new epidemic caused by the spruce beetle has killed old growth forests, especially in the South San Juan and Weminuche Wildernesses.

I see significantly more people exploring the first seven miles, from trailhead to perhaps that lower alpine lake in wilderness, now than 40 years ago; and there are so many more people climbing the Fourteeners! Ironically, I do not see that many more people today doing the more remote, multi-day trips into wilderness. The exception to this are the multi-day trips along the Colorado Trail and, to a lesser degree, along the Continental Divide National Scenic Trail.

Mountain goats have multiplied in this time and probably at the expense of big horn sheep populations. I see them in so many mountain ranges today. Elk and deer seem to be doing well, probably because of

the economic incentives of hunting revenues to keep them ubiquitous. And how about all of those moose? Twelve moose introduced into North Park in 1978 have turned into over 2,000 living in so many Colorado mountain valleys.

What led you to become a conservationist? Was there a particular cause or event that grabbed your attention?

I became a visible environmentalist in 1992 when Senator Tim Wirth was working on his 1993 Colorado Wilderness Bill. Tim invited me to photograph 750,000 acres of prospective wilderness so he could show his fellow members of Congress more than just map boundaries of what would be protected. We published a book called Our Wilderness Future that was given to all of Congress. In 1993 the bill was passed into law, and, among others, my beloved Sangre de Cristo Mountains were protected.

That fall, Tim asked me to speak to 500 people at the University of Denver Law School and show slides of what had been preserved, as well as sell and sign books. This was the first time in my career that I “preached the gospel according to Mother Nature!” I was very nervous but soon discovered that people had come to see the images as much as listen to me, which made my fear of getting up in front of so many people and incipient public speaking career much easier.

How do you determine your photography schedule? I’d imagine there are specific locations that you plan on being during certain times of the year, right? And do you have a favorite location to photograph?

Though I photograph wilderness in all seasons, summer is most productive for me. I have explored and photographed all of Colorado’s wilderness areas but still love returning to both new and favorite drainages. For 40 years my favorite place to be is, and always will be, an alpine cirque with multiple levels of tarns. Wildflowers, creek cascades, and mountain reflections are my most iconic images. These days I also make time to explore wilderness in other parts of the U.S., including Alaska. In the summer of 2013, I spent 18 days llama-packing 140 miles along trails of Wyoming’s Wind River mountains, the Bridger and Popo Agie Wildernesses. This summer I will explore Idaho’s Sawtooth Wilderness and Montana’s and Wyoming’s AbsarokaBeartooth Wilderness.

portion of the U.S. would be like without it?

For me, our wildest places are our best places. Wilderness is an unequalled stabilizing force that is always there and that connects us with our beginnings. The personal sense of security derived from things permanent, like wilderness and God, is more important now than ever before as the world becomes more crowded and chaotic. And yet, wilderness is not a static landscape frozen in time but a living, dynamic environment full of the fury and calm of nature. To explore vast wildernesses, we must abandon worldly schedules and immerse ourselves in the flows and patterns of nature—rise with the sun, sleep with the darkness, huddle from the storm.

You have been generous enough to provide a free exhibit that has been traveling throughout the state celebrating the 50th Anniversary of the Wilderness Act. What motivated you to do this? Also, what comes to mind when you think of the next 50 years for wilderness?

A burgeoning population and warming climate makes the urgency of protecting our remaining wilderness greater than ever. The salvation of humanity lies in the preservation of Earth’s natural systems.

Longs Peak, Wild Basin, Rocky Mountain National Park. Photo by John Fielder Sunrise, Turret and Pigeon Peaks, Weminuche Wilderness. Photo by John Fielder

We can only survive in the long term by living in concert, not conflict, with them. If we allow our ecological goose to be cooked (quite literally), we cook our economic goose. And the reverse is true. Only societies with healthy, happy, and prosperous people protect nature.

Here is my advice for people who want to be happier, healthier, and more prosperous: Attach yourself to things spiritual, or permanent, such as Earth itself. Resist infatuation with shallow, ever-changing things like technology and television that promote conformism. you will become more secure with yourself and those around you. A relationship with nature breeds humility and quells the ego. With that you will better appreciate your fellow humans, reduce conflict, and chaos will succumb to order.

You’ve been a photographer for over 40 years. What are the challenges and benefits with today’s digital format compared to film? Also, do you prefer one format over another?

The days of carrying 65 pounds of large-format camera gear up and down mountains are thankfully over. Smaller and lighter digital cameras make extensive travel so much easier, and they make better photographs. The dynamic range of color film is 6 stops of contrast that often rendered some parts of the photograph either black or completely washed out. Digital sensors in both SLRs and point & shoot cameras provide a dynamic range as great as 13 stops, allowing one to manifest much more detail in shadows and highlights simultaneously within the same purview. We can make nature look more real, and that is a good thing when you want to attract advocates!

Do you ever try and communicate anything through your photographs?

It is one thing to view photographs of nature in a book or on a wall, entirely another to be in nature. There is no substitute for tasting, smelling, feeling, hearing, as well as seeing nature. The sensuousness of the natural world is the best recruiter of advocates to protect and preserve the miracle of 4 billion years of the evolution of life on Earth. I hope that my photographs get people outdoors.

Other than some rangers and possibly a few guides, you probably spend more time in Colorado’s wilderness areas than anyone else. Are there any stories about your experiences with the natural environment that you’d like to share?

I told this story to Trail & Timberline a few years ago (T&T Issue 1007). Cresting a ridge at 13,000 feet in the Needle Mountains of the Weminuche Wilderness, I spied a billy goat 50 yards away, lying in the soft tundra and snoozing. I approached him slowly but deliberately. Trying to show no fear, I stopped 5 feet away from him. He did not move nor even look up at me. I dropped to my knees and crawled next to him. I lay prone and parallel to his body with my head propped on my hand. I was only 2 feet away, yet he continued to ignore me. I began to talk to him. For the next 30 minutes I enjoyed the most remarkable wildlife encounter of my life. I spoke to him all the while, making statements and asking him questions. I asked him about living throughout the year above the trees in one of the most beautiful places on Earth. I told him about my life as a nature photographer and my appreciation for his place and all things wild and natural. The entire while he slumbered by my side, this 250-pound miracle of a creature, not once looking at me, not once answering a question (a good thing, otherwise this would have been only a dream). I can only assume that my voice soothed him and that my presence and proximity was acceptable. △