4 minute read

People in Science

Henrietta Lacks, The HeLa Cell Controversy and Good Clinical Practices

The voluntary consent of the human subject is absolutely essential

-Excerpt from the Nuremberg Code of Medical Ethics

Henrietta Lacks (Hennie, for her family), was born on August 1, 1920, in Roanoke, Virginia, USA. Henrietta was part of a large family dedicated to tobacco growing. She lived a happy childhood, however, after the death of her mother and in the midst of the economic crisis of the time, her father made the decision to leave his children in the care of his close relatives.

Because of this, young Hennie went to live at her paternal grandparents’ home, which she always considered her family home. There Henrietta would meet her future husband David Lacks, who was her uncle’s son, and therefore Henrietta’s cousin. The Lacks family lived under the segregationist regime of the time, so their employment opportunities were limited. When she became pregnant in 1935 with David Lacks, Henrietta decided to leave the world of agriculture and seek new prospects in the city, where the family prospered thanks to the growing steel industry. Some time later, when Henrietta was only 31

years old, she went to Johns Hopkins Hospital for abnormal vaginal bleeding, where she was diagnosed with cervical cancer. From that moment on, she began a battle against cancer through treatments and techniques of the time, however, the tumor invaded her body. Hennie finally passed away on October 4, 1951 at 00:15 hours at Hopkins Hospital, and was buried in Lacks Town, near Clover.

HeLa cells

When Henrietta consulted Dr. Richard W. TeLinde (Gynecologist and Researcher at Hopkins Hospital), she underwent several studies, which determined that she had a cancerous tumor, so Dr. TeLinde decided to take biological samples to examine it, and these samples were sent to Dr. George Gey’s department.

Dr. Gey was obsessed with the creation of a cell culture of human origin that could be “immortalized”, as already existed in mice. As the director of the Cell Culture Department at Hopkins Hospital, he was able to design a study to create a cell line that would act on cervical cancers and decrease their mortality rate. However, his experiments had not been successful and by the time Henrietta’s cells arrived at the laboratory, Dr. Gey cultured, analyzed and labeled them under the name HeLa.

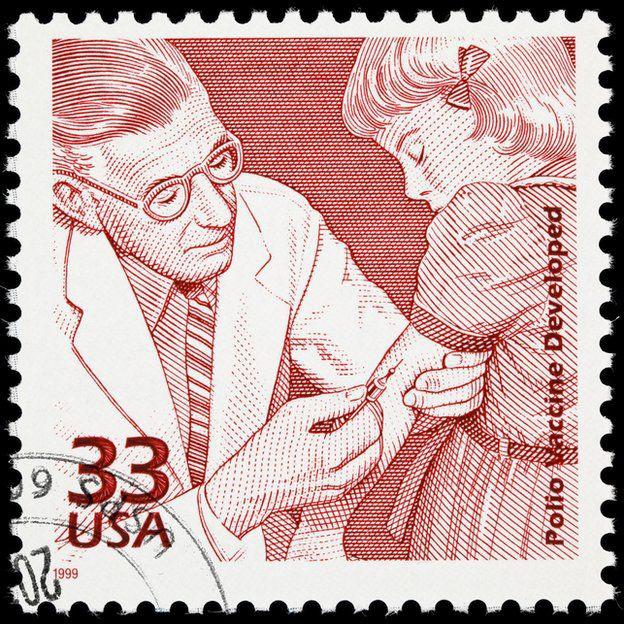

At first, the cell’s growth rate was high, but instead of dying, as eventually expected, they doubled at a steady rate every 24 hours. So, by repeating the process, Dr. Gey had achieved an immortal cell line. The Tuskegee events saw the installation of the world’s largest HeLa cell factory, which was used exponentially to test the polio vaccine, saving millions of people.

Since then, HeLa cells have been used in medical treatments, traveled to space, were used in atomic experiments, and were the first cells to be bought and sold by laboratories around the world. However, there was a problem. In the 1940s and 1950s, it was unclear whether it was necessary to ask for permission (informed consent) to use human tissues for research.

It wasn’t until 1973 that Henrietta’s family learned that their relative’s cells were still alive, so they consulted with lawyers to find out if they had rights to them; They have since been embroiled in legal battles.

In 2021, the WHO held an event commemora-ting Henrietta and the many scientific advances thanks to HeLa cells, where the WHO Director-General said: “What happened to Henrietta was wrong, Henrietta Lacks was exploited. She is one of many women of color whose bodies have been misused by science”.

Blanca M. Peredo Vazquez

CTA at DROX Health Science