7 minute read

3.1 - Historical Progression

from Residual Farmland

by clareknecht

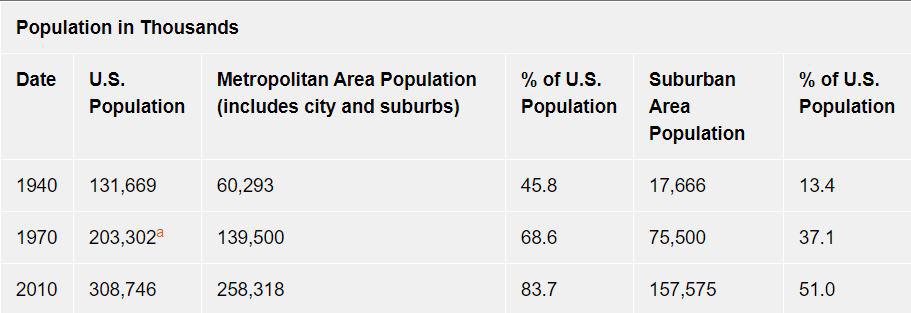

Excerpts taken from Becky Nicolaides and Andrew Wieses’ publication called “Suburbanization in the United States after 1945” is used to preface the significance of suburbia. Mass migration to suburban areas was a defining feature of American life after 1945. Before World War II, just 13% of Americans lived in suburbs. By 2010, however, suburbia was home to more than half of the U.S. population. The nation’s economy, politics, and society suburbanized in important ways. Suburbia shaped habits of car dependency and commuting, patterns of spending and saving, and experiences with issues as diverse as race and taxes, energy and nature, privacy and community. The owner occupied, single-family home, surrounded by a yard, and set in a neighborhood outside the urban core came to define everyday experience for most American households, and in the world of popular culture and the imagination, suburbia was the setting for the American dream.

[Image 15] Pioneer mass-builder Fritz Burns developed Westchester in the late 1930s, devising many of the mass-production techniques adopted by postwar suburban builders through the United States.

Advertisement

Postwar suburbia was built upon a prewar metropolitan landscape characterized by “segregated diversity,” a heterogeneous mix of landscapes, functions, and populations that emerged in the late 19th century. Prewar commuter suburbs with lush landscaping and large houses abutted farms and orchards, modest streetcar suburbs, and Main Street shopping districts. Elsewhere, smokestacks broke the rural skyline alongside worker housing. As geographers Richard Harris and Robert Lewis conclude, “Prewar suburbs were as socially diverse as the cities that they surrounded.”1 Ironically, this heterogeneous landscape, and especially the open spaces lying between and beyond it, was the setting for a massive wave of postwar suburbanization that was characterized by similarity and standardization. This history originated in the chaotic transition to peacetime society after 1945. World War II migrations, military deployment, and demobilization compounded a housing shortage that dated back to the Depression. In 1945, experts estimated a shortage of 5 million homes nationwide. Veterans returned to “no vacancy” signs and high rents. As late as 1947, one-third were still living doubled up with relatives, friends, and strangers. American family life was on hold.

The solution to the housing crisis emerged from a partnership between government and private enterprise that exemplified the mixed Keynesian political economy of the postwar era

The Federal government provided a critical stimulus to suburbanization through policies that revolutionized home building and lending, subsidized home ownership, and built critical suburban infrastructure, such as the new interstate highway system. Private enterprise, for its part, applied new mass production techniques and technologies tested during the war to ramp up home building. Key to this partnership was a New Deal–era agency, the Federal Housing Administration (FHA). At the heart of FHA policy was a mortgage insurance program that took the risk out of home lending and made the long-term (25–30 years), low-interest home mortgage the national standard. The FHA also granted low-interest construction loans to builders and established basic construction guidelines that set new nationwide building standards. Along with a companion program in the Veterans’ Administration (VA) created by the 1944 GI Bill, the FHA stimulated a flood of new construction that brought the price of home ownership within the reach of millions of families. “Quite simply,” concludes historian Kenneth Jackson, “it often became cheaper to buy than to rent.” Jackson also notes that these programs had a pro-suburban bias. FHA and VA requirements for standard setbacks, building materials, lot sizes, and other features ruled out loans to large sections of urban America while giving preference to new homes on the suburban fringe. By the 1950s, as many as one-third of home buyers in the United States received support from the FHA and VA programs, and home ownership rates rose from four in ten U.S. households in 1940 to more than six in ten by the 1960s.

The vast majority of these new homes were in the suburbs.

Equally important to the postwar boom was a revolution in construction. In response to pent-up demand and new federal supports, a cohort of builder-developers modernized home building to achieve mass production. The new builders were young, bold, and creative; many were the children of immigrants. Using techniques pioneered by prewar builders, such as Fritz Burns of Los Angeles, and refined through work on large war construction projects, contractors streamlined home building, employing standardized parts and floor-plans, subassembly of doors and windows, and subdivision of labor to minimize the need for skilled or unionized workers. The scale of building took off. Whereas “large builders” in prewar America might have built 25 homes per year, by the late 1940s, large firms were building several hundred homes per year.

Annual housing starts leaped upward from 142,000 in 1944 to an average of 1.5 million per year in the 1950s.

The media hailed developers like Levitt as “community builders” because they not only subdivided land and built houses but created whole communities from scratch. Despite these accolades, historian Dolores Hayden points out that the drive for profit pushed community planning to the back burner in much of postwar suburbia. Developers often set aside space for civic facilities, but local taxpayers were responsible for the cost of parks, playgrounds, libraries, and other public amenities. . Levittown, Long Island, for example, was built without public sewers or even adequate septic tanks, forcing home

-owner/taxpayers to make expensive upgrades after the Levitts moved on. Smaller builders were often even more frugal. Thus, for many new suburbanites, the companion to low housing prices was a high tax bill. The ongoing struggle of many suburbanites to build a sense of community in the unfinished civic landscape of mass suburbia was a legacy of this era. New residential suburbs represented just one element of the postwar suburban trend. By the early 1950s, commercial developers, corporate headquarters, big retailers and other businesses, were also migrating to the suburban fringe, setting the stage for a wholesale reorganization of metropolitan economies by the end of the century. Aided by federal tax policies such as accelerated depreciation that subsidized new buildings over the maintenance of existing ones, retailers like Macy’s and Allied Stores opened new suburban branches to capture consumer dollars that traditionally flowed to their downtown stores. Architect-developers like Victor Gruen—who designed many early suburban shopping centers, including the nation’s first indoor shopping mall, the Southdale Center in suburban Minneapolis, 1956—evangelized the new shopping center as a modern civic center, a privately-built “public” space that would replace the traditional downtown. Corporate headquarters, and other offices also began a slow shift to suburban locations. Attracted by the prestige value of elite suburbia, Fortune 500 companies such as General Foods, Reader’s Digest and Connecticut General Life Insurance built landscaped campus “estates” in suburbs such as Westchester County, New York, and Bloomfield, Connecticut, during the 1950s, signaling a trend that peaked in the 1980s. In the Washington, D.C., area, government agencies also shifted to suburbia, led by the Central Intelligence Agency, which broke ground on its new campus headquarters in Langley, Virginia, in 1957.

In recent years, the suburbs came under a new round of criticism, this time perhaps the harshest yet. While bands like Green Day and Arcade Fire wailed on the suburbs for killing youthful freedom and joy...

echoing generations of suburban critics, writers like Fortune Magazine’s Leigh Gallagher took it a step further by declaring “The End of the Suburbs” in her 2013 best-selling book. The alarm was justifiably stoked by the Great Recession of 2007–2009, which devastated millions of American families who lost their homes to foreclosure, or saw their suburban home values plummet. MThese concerns, along with worries over sprawl’s negative impacts on climate change and millennials’ desires for more urban styles of living, fueled a back-to-the-city movement. Writers like Gallagher contended this was the end of the line for the suburbs. Americans were finally turning their backs on the form, reversing a long history of sprawling development.

“Speaking simply,” she wrote, “more and more Americans don’t want to live there anymore.” Yet, different trends suggest otherwise.

Immigrants, young families, seniors emotionally attached to their homes, and others continued gravitating toward suburban homeplaces, for a host of reasons—whether good schools, nostalgia, ethnic familiarity, jobs, or few good alternatives.

Recent data suggests a return of suburban growth, after a post-recession slowdown.

[Image 16] Sources: U.S. Census Bureau, 2010 Census,

In turn, contemporary suburbia is showing signs of change, adaptation, and stasis—all at once. As Manuel Pastor noted at a recent roundtable discussion on Suburban Crisis, Suburban Regeneration “the suburbs have a future, but the future ain’t what it used to be.” Some suburbs have transformed into ethnoburbs that support the values and needs of new immigrants, some have spawned social justice movements, others are adapting to aging populations through innovative retrofitting, while still others persist seemingly untouched, clinging to deeply entrenched traditions. The discourse of suburbia’s demise may have attracted much public attention, but it masks the fascinating ways that the nation’s suburbs continue to claim a central, dynamic place in American life.

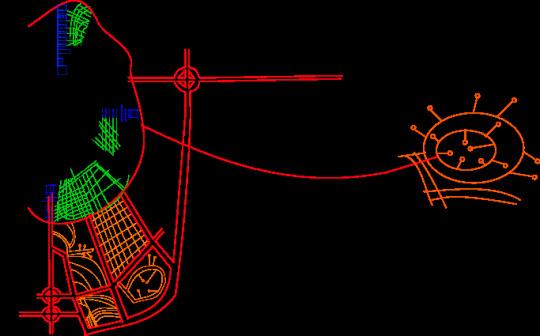

Urban Neighborhood c. 1750-1850

Urban Neighborhood c. 1860

Urban Neighborhood c. 1920

Urban Neighborhood c. 1940

Urban Neighborhood c. 1970

Urban Neighborhood c. 2000 - current Railway Suburbs

Streetcar Suburbs

Automobile Suburbs

Suburbia

Exurbia