14 minute read

Alumni Profile: Eliot Rabin, ’64

and a cashmere sweater in the other With a toilet brush in one hand

BY J.J. WALLACE

Eliot Rabin leans on a clothing rack, keeping a watchful eye on Peter Elliot Blue, his flagship menswear store located on Lexington Avenue in New York City. While the store has changed locations over the years, the quality of clothing and accessories remains.

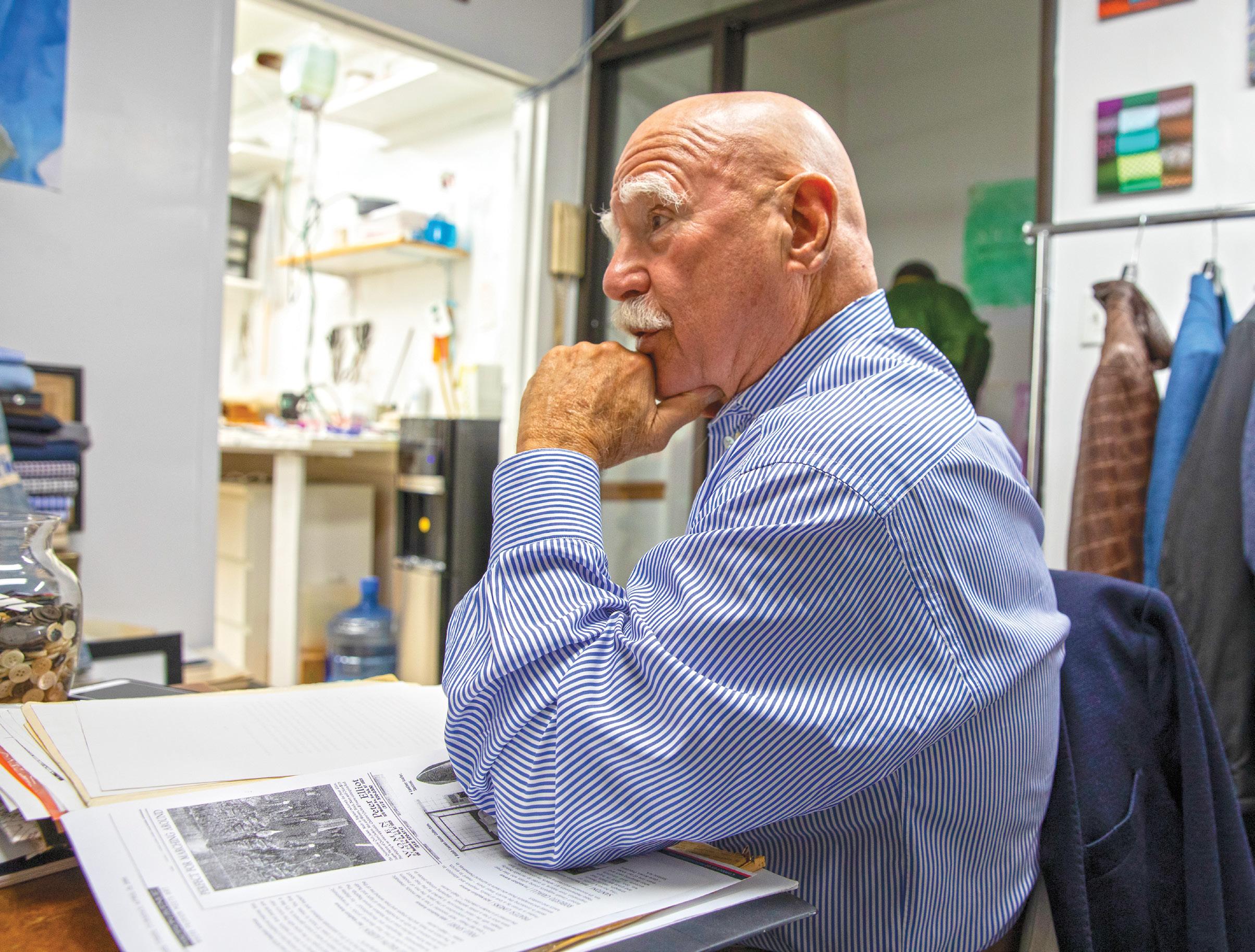

n a small storeroom off Madison Avenue that serves as a makeshift office, Eliot Rabin, ’64, sits in a bistro chair at a table telling stories, many of which are not suitable for print and many, outlandish—one involving wine, an aging dictator and a toupee that he unceremoniously tossed into a bowl of bouillabaisse. Hanging behind him on a portable rack are a pair of slacks, a couple of blazers and an alligator jacket that retails for $275,000. The room is filled with bolts of fabric, pincushions, spools of thread, and, oddly, a leather hippopotamus. In an adjoining room a woman from Uzbekistan by the same of Stella is working at a sewing machine. At 77, Rabin, who also answers to the name Catfish Eliot, is bald with a trim mustache and an impressive pair of white eyebrows that frame animated brown eyes. He is wearing a blue-andwhite-striped dress shirt and khaki slacks. A chunky silver Hermes bracelet adorns his left wrist, and a complicated looking watch that he bought in Paris, his right. Rabin is not tall, but his energy fills the room, and he has big ideas that get him noticed. I

Rabin's iconic New York City logo can be found on his awning—seen at the corner of Lexington Avenue and E. 72nd St. above windows filled with the latest in quality menswear. Inside, Rabin's attention to detail continues. A smaller awning replica is mounted in the store.

IN THE BACKYARD OF THE CITADEL

Rabin was born in Charleston in 1942 to Annie and Leon Rabin. His father owned Leon’s Men’s Wear on King Street, and later, in the 1970s, his mother opened a women’s clothing store in North Charleston called Dawn’s Village Shop. Rabin and his sister Eileen, who was three years younger, grew up in Charleston. First, they lived on Gordon Street and then they moved to Grove Street and 6th Avenue, the backyard of The Citadel. Rabin played marbles, hopscotch and Superman in a tree, an imaginary game that landed him a broken leg. He played Little League Baseball and attended Hebrew school, and in their English newsboy hats, he and his friends dangled from trees behind the shooting gallery by the Ashley River smoking rabbit tobacco, a medicinal herb that grew wildly.

The family had a beach house at Station 21 on Sullivan’s Island. Rabin and Eileen made bows and arrows out of the reeds that grew in the sand dunes. They rode horses on the beach and went fishing and water skiing. Back in town at Hampton Park, Rabin played basketball with both black and white friends until local laws segregated their play. “We never thought about it,” says Rabin. “And then they passed these laws and everything began to polarize because they did a negative thing when everything was positive.”

As a Jewish boy growing up in Charleston, Rabin never encountered anti-Semitism. “Charleston had the largest Jewish population up until the Civil War and later supported an incredible number of synagogues for the size of the population at that time.”

The Rabin children learned the family business from Leon, who handed them a broom at a young age. Remember one thing,” Rabin recalls his father saying, “If you can fold a cashmere sweater with your left hand and clean the toilet with your right hand, you can be in business.”

When Rabin was about 8 years old, he remembers a Saturday afternoon inside the store when he heard the screech of car tires. A 13-year-old black boy named Earl Huger had been hit by a car on King Street. “My father shut the doors of the shop, picked up the kid, put him in the car and drove to St. Francis Hospital.”

At St. Francis, the security guard told Leon that the Catholic hospital did not accept black patients. “And my father looked at him and pointed to the statues of Mary and Jesus and said, ‘Here’s Mary. Here’s Jesus. I’m leaving him right here. If he dies, it’s on you.’”

After Huger got out of the hospital, he worked at Leon’s until the age of 18, when he enlisted in the Air Force where he became the top sergeant major.

FROM LESESNE GATE TO AUGSBURG

In the fall of 1960, Rabin was one of about 20 freshmen from Rivers High School to enroll at The Citadel. He had letters of acceptance from Tulane, Vanderbilt and the University of Tennessee, but it was the military college in his hometown that captured his attention. “It was the best thing that could have happened,” says Rabin. “I had put myself in a position, in a place where I had to sit at my

desk.”

Rabin’s sister Eileen Sorota remembers going to The Citadel to see her brother after he matriculated. When her cousin, Susan, pointed to Rabin, Sorota did not recognize him. “He had lost about 15 pounds. It was a tough year for him. A high school friend had quit, but my brother was determined. Now he wears that ring as proudly as any alumnus.”

Freshman year may have been challenging for Rabin, but the India Company upper-class cadets were not without their own challenges. On a cold January morning, Rabin and some of his classmates snuck into the bathroom, where they lined the toilet bowls with Saran wrap and covered the black toilet seats with shoe polish.

That morning as the freshmen stood at attention in the quadrangle, they heard a loud ruckus coming from the bathroom. “They came down with fire in their eyes. We didn’t care. We were laughing so hard, and they tried to get us to stop—we were laughing and doing pushups. It was one of the funniest things that ever happened at the school.”

With that same air of reckless abandon, Rabin embarked on life after The Citadel. In London he

From the 1964 Sphinx: Chaplain Crumpton, Tony Barzuzanes, Bill Hankinson and Eliot Rabin select music for a Carrillon Tower recital.

Rabin greets customers and passersby outside of Peter Elliot Women on Madison Avenue in New York City, just a block from Central Park and the Museum of Modern Art. He credits the success of his business to personal relationships he has cultivated with his customers over the years.

pursued a degree in the newly emerging field of space law. In a small class with students who were mostly the sons of tribal chiefs from Africa, Rabin remembers a Professor Burton, who called him “wet behind the ears” and who planned an unusual course of study: “I want you to hitchhike through Europe. I’m going to send you to English-speaking libraries, and you can send in your assignments.”

Rabin needed no further encouragement. With his guitar on his back, he was off—Dover, Ostend, Belgium, Frankfurt, Munich, Innsbruck, Trieste. And in May, instead of returning to London for exams, Rabin was living it up in the south of France.

When he returned to Charleston, Rabin was drafted. “So I went to Fort Gordon, Fort Dix for advanced individual training for combat and eventually to Fort Benning. I went to officer candidate school, which turned out to be very easy after The Citadel, and then I went into the service, and loved every single minute of it.”

Rabin was a battalion S4 logistics officer in tank gunnery maneuvers in Gravendeel, West Germany, when he was charged with planning a party for a retiring colonel, John B. Wadsworth. Wadsworth loved Old Grand-Dad bourbon, so Rabin made a big cake to resemble a bottle of Old Grand-Dad, and inside the cake were actual bottles of the bourbon. The party was a success, and Rabin was ordered by the commanding general to take over the failing officers’ club in Augsburg. When Rabin argued that he knew nothing of running a business, the general countered, “Boy, you’re Jewish, aren’t you? You Jews know how to make money.”

Rabin was offended, and more importantly, he wanted to go to Vietnam, but he knew that an order was an order. “So I took it over, and it made money, and I got the Army Commendation Medal. Big deal.”

But it was a big deal—Rabin’s creative flair was getting noticed and he found himself in his father’s entrepreneurial footsteps.

FROM BLOOMINGDALE’S TO OSCAR DE LA RENTA

In the early 1970s Rabin began working at Bloomingdale’s in New York City as an assistant buyer. On the floor next to him was another young Jewish man and the designer of a line of wide, handmade ties being sold by Bloomingdale’s. His name was Ralph Lauren.

Rabin’s prophecy proved true. “As a result, the revolution in menswear began right away. Everybody

came. It was peacocks. It was Studio 54. It was cocaine. It was all this crazy stuff in this crazy city.”

At Bloomingdale’s, Rabin hustled. When a disgruntled buyer quit, leaving behind a big mess and phony orders for the holiday season, Rabin called Leon back in Charleston to find a supplier. “By the time I was done, I filled the department. I was a hero, 36 percent ahead of the rest of the store for the next two years.”

While he was buying for Bloomingdale’s, a company called Bratten Apparel tried to sell Rabin a line of men’s clothing. “Your line is very good. The quality is excellent,” he told them. “But you look like Farah. You look like Levi. And I don’t need that. I need stuff with color.”

Rabin’s words resonated with the company, and they hired him to design. He designed two color pairs that he featured on Eisenhower jackets, bell bottom pants and knit sweaters. Grapefruit and Grass—chrome yellow and Kelly green—was a crossing plaid on an ecru background. The second pair was called Ice Blue and Hot Orange.

The first customer to see the line—Stanley Marcus of Neiman Marcus. After Bratten Apparel, Rabin designed for Chester Boutiques which held the licenses for Givenchy and Emilio Pucci and Cortefiel. He colored Pucci prints in Florence, Italy, before going to Spain to design leather goods for Cortefiel. And then he went to Oscar de la Renta where he designed the entire men’s line, combining rubber Hunter boots with denim jeans, a black velvet jacket and a banded collar tuxedo shirt.

THE UPPER EAST SIDE

After Oscar de la Renta came Peter Elliot,* a men’s store Rabin opened on the Upper East Side of New York with a partner named Peter Lonergan. Peter Elliot was a combination of their first names. The name lasted—

their partnership did not, and after only two months Rabin became the sole proprietor. Peter Elliot has been in business now for 43 years. There are two stores, a men and boys’ store on Lexington Avenue and a women’s store on Madison Avenue.

Rabin’s success is part ingenuity, part luck. Not long after he went into business, he put together a window display that featured a female mannequin with her foot propped up on a lion’s head and a rifle in her hands. She wore a split skirt, and on her leg was an alligator and snakeskin belt. Within 24 hours of the display’s debut, a women’s rights activist hurled a brick through the window, and Rabin made the front page of The New York Times. “Eliot is a creative person,” says Sorota. “He has imagination, a phenomenal eye and excellent taste. He’s a pioneer—he was the first to carry some of the classics, like Max Mara and Isaia.”

Rabin’s clients include hedge fund managers, socialites, actors and actresses. Isabelle McNally, the manager for the women’s store who has been working for Rabin for 18 years, says that Peter Elliot has become a tradition in families. “The boys’ line is a niche, luxury business. The future is younger people and the quality of the product. Families shop with us, and now we have this incredible thing—these young people, who have shopped with us from a young age, are now in college and coming back.”

Rabin’s inventory radiates decadence. Seamless cashmere sweaters are made in Italy, England and Scotland using premium wool from the neck of the goat that is gently washed in soft water that does not strip the oils from the yarn. Luxuriously soft cotton button-down shirts made in America of two-ply cotton with pearl buttons retail for $175 apiece. And elegant jewel-colored silk ties in capricious designs add an elegant touch to a single-needle stitch Italian suit. “Long after the price is forgotten,” Rabin is fond of saying, “the quality remains.”

ELEVEN FLIGHTS OF STAIRS, A FEW PUSHUPS AND THE NEXT CHAPTER

As he approaches 80, Rabin has no plans to retire. He’s brimming with ideas and opinions. He says he’s too busy to go to the gym, so he walks the 11 flights up to his Manhattan apartment, and in the spirit of his Citadel days, he drops down for a few pushups. When he was 60, Rabin embarked on yet another great adventure—fatherhood. Joshua Blue Enright Rabin, now 17, is getting ready for college. Rabin hopes he will choose The Citadel.

In 2018, Rabin ran for Congress, challenging New York’s 12th district incumbent Representative Carolyn Maloney. Maloney won the race, but the retail fashion designer with a meager campaign budget took 12 percent of the vote. “If you want to fix our country, you need to bring back the draft—you need to rebalance our society,” says Rabin who toyed with the idea of running for president.

The next chapter for Rabin remains to be seen. He has a lifetime of wisdom and adventure to his credit, and whatever path he chooses, he is sure to tackle it with his usual energy and aplomb. •

2020 ALUMNI AWARDS

Nominations due by August 1 for:

Alumnus/a of the Year Honorary Life Member Distinguished Life Member Young Alumnus of the Year District Director of the Year The Carroll N. LeTellier Award If you know of alumni who you think are deserving of consideration for any of these awards, please complete a nomination form. Both nominees and their nominators are required to be alumni members of the Association in good standing (except the Honorary Life Member award). More information about the qualifications for each award can be found on the Association's website.

Honorees will be recognized at the Alumni Association Annual Meeting at Homecoming. For more information or to nominate: www.citadelalumni.org/awards.

The newest addition to the Distinguished Citadel Alumni List (DCAL) is Morris D. Robinson, ’91. The 2017 commencement speaker and honorary degree recipient was added to the DCAL in December for his accomplishments.

A native of Atlanta, Georgia, Robinson’s desire to play college football resulted in a scholarship to play for The Citadel where he was a three-time 1-AA All American offensive lineman, graduating in 1991 with a bachelor's degree in English. As a freshman, he became known as the “singing knob" for his impromptu serenades to fellow cadets and his performance of "O Holy Night" at the annual Christmas candlelight concert. He also co-founded and sang in the gospel choir. He was featured in Sports Illustrated and on CBS Sports College Football Today. In 1991, he was invited to sing the national anthem at the NBA All-Star Game in Charlotte, North Carolina.

After graduating he lived in the Washington D.C. area. His wife Denise arranged a successful tryout with the Choral Arts Society of Washington. After moving to New Hampshire he attracted the attention of the Boston University Opera Institute. He entered the program in 1999 and that same year made his operatic debut with the Boston Lyric Opera as the King of Egypt in Aida. He went on to become one of only nine singers in the world accepted into the Lindemann Young Artist Development Program, sponsored by the Metropolitan Opera. His debut at the Met in 2002 was in a production of Fidelio.

Recently Robinson performed in the musical Showboat in the role of Joe. In the fall of 2016, he made his debut at La Scala in Milan, Italy, with the lead role in Porgy and Bess. Robinson has also performed regularly with the National Symphony Orchestra and the New York Philharmonic. He was the second person to be named artistin-residence for the Atlanta Symphony Orchestra, and in 2017 he was named an artistic advisor for the Cincinnati Opera. He was the first black artist to sign a recording deal with a major classical label. In 2019 he was named resident artist at Harvard University.