6 minute read

IN THE BEGINNING

Gen. James E. Oglethorpe seemingly had a hand in every aspect of Savannah’s early history, including the concept of its street plan, the consultations over who to take to settle it, and the choice of its location. So it was altogether fitting that he also aided in the initial phase of construction.

Advertisement

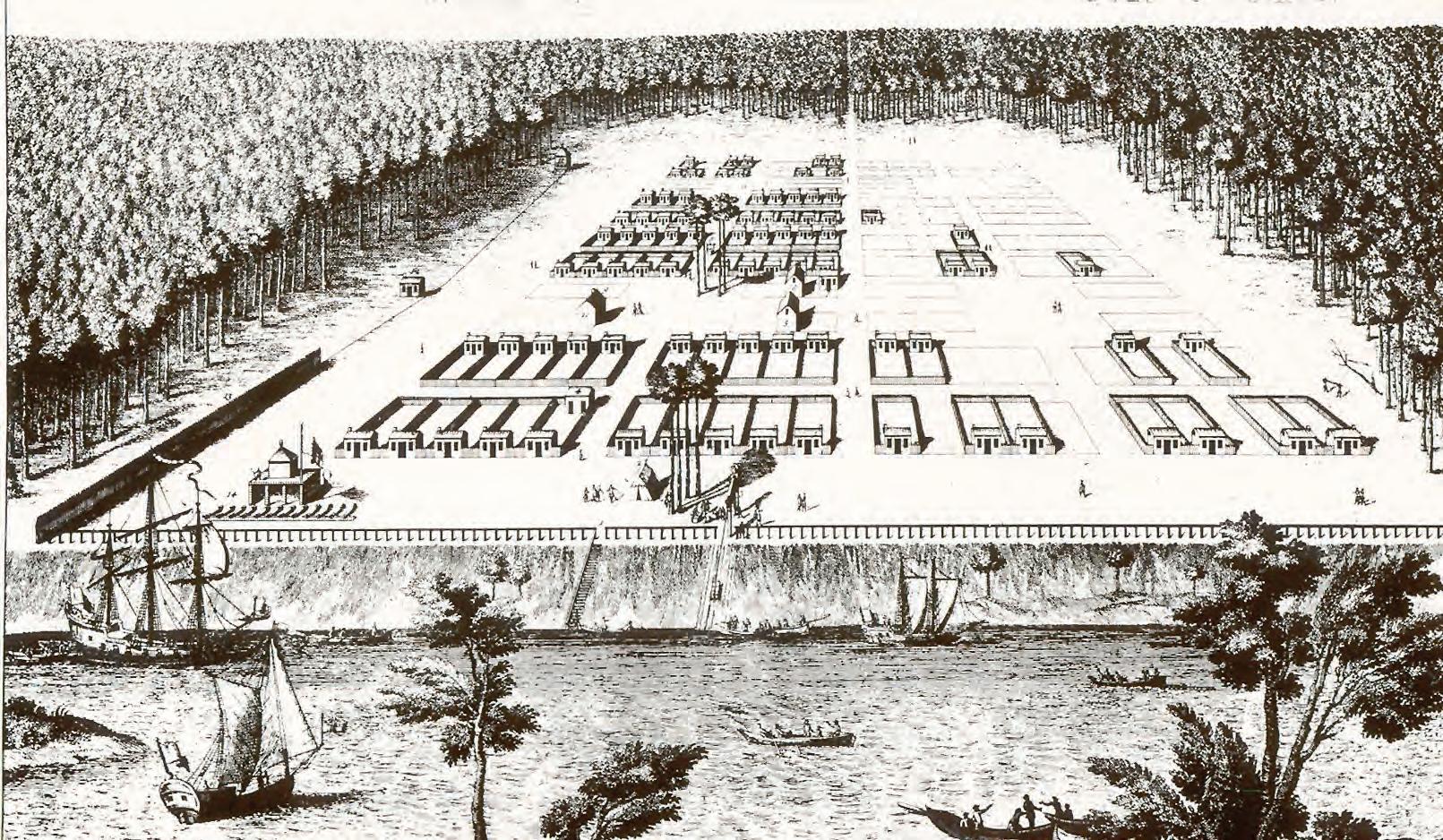

On March 1, 1733, less than a month after the colonists’ arrival, Oglethorpe ceremoniously drove in the first pin of Savannah’s first house. By June, eight additional framed dwellings, and a smith’s forge, had been built. Shortly thereafter, two blockhouses and a guardhouse added security to the project. A year later, when Peter Gordon crafted his famed map of the city (above), some 100 acres had been cleared, and Savannah, with the central elements of its plan already clearly delineated, was fast taking shape. Placed on identical 60-feet-wide by 90-feet-deep lots, its first houses were identical as well.

They were simple sawed-timber cottages, measuring 16 feet in width, 24 feet in length and one-and-a-half stories in height. The basic floor plan was one large room in front, two smaller rooms in the rear and a loft or attic above. It was all floored with inch-and-a-half planks, and raised some 2 feet on a log foundation. The pitched roofs were layered with tarred shingles or thatched with palmetto leaves. Insulation? That would have been straw or marsh grass.

When John Reynolds, the first royal governor of Georgia, landed in Savannah on Oct. 9, 1754, the city had some 150 houses scattered about. It was not a prosperous time – the phrase “poor as a Georgian” was often voiced in neighboring South Carolina – and further proof of the colony’s struggles came a week later when one of the walls at the Council H o use on present-day Wright Square caved in during a meeting chaired by the new governor.

For tunately, in the early-1760s, a line of new wharves was built along the waterfront, and the resultant sharp spike in shipping, particularly with ports in the Caribbean, saved the city’s economy. By 1770, six squares – R e ynolds, Johnson, Ellis , O glethorp e, Wright and St. James (now T elfair) – alon g with their surrounding houses, had been completed.

A spate of construction also added to the city’s appeal. These newer houses, although not grand, were often painted red or blue, and boasted side piazzas or porches.

Three houses constructed in downtown Savannah around that time are still standing (photos, opposite page, clockwise from top left).

The Christian Camphor Cottage at 122 E. Oglethorpe St. was built circa-1760 and was raised onto a brick foundation in 1871. It is the only building that dates back to the Revolutionary War era.

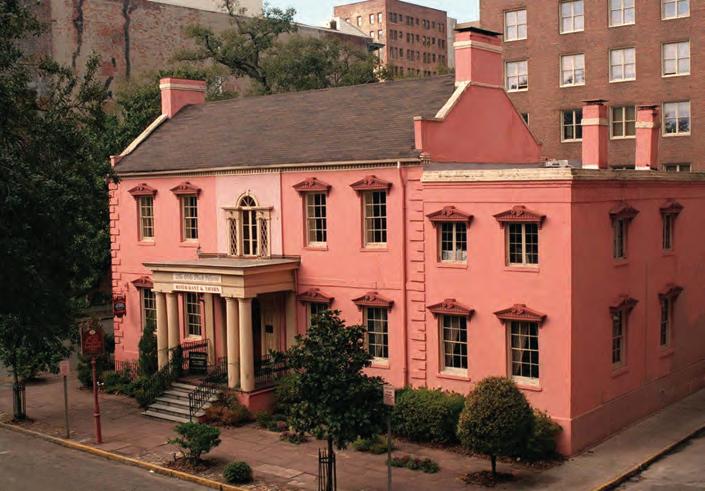

The Habersham Hous e, now much better known as the Olde Pink House, was built circa-1789. The porch was added after the War of 1812, and further renovations were made in the 1870s.

The Spencer-Woodbridge Hous

Habersham St. was built in 1791. e at 22

These three houses are noteworthy because they survived Savannah’s first great disaster, the downtown fire of 1796. It started on the evening of Nov. 26 in the bake house of Mr. Gromet on Market Square and raged for some six hours, fed by wood-shingled rooftops and spread by strong winds from the northeast. When it was over, much of the old town – from Barnard Street in the west, to Abercorn Street in the east, and from Bay Street in the north to the city common on Oglethorpe Avenue in the south – had been leveled. In all, some 229 houses and 146 outbuildings were consumed by the flames.

The Columbian Museum and Savannah Advertiser reported on Nov. 29 that 375 chimneys were “standing bare” and that some 400 families were homeless.

With the help of builders from the North and Europe, Savannah quickly began to rebuild. In addition, Adrien Boucher, the city’s first trained architect, arrived at about

(continued from previous page) that time as well. A refugee from the French Revolution, Boucher lived in New York for several years before moving to Savannah, where he sought to create “elegant and strong” buildings.

He is credited with planning the City Exchange, which was initially occupied by commercial tenants and stood on the same site as the present-day City H all un til its destruction in 1904, the Berrien H o use on Broughton Street and the H o uston-Screven H o use on A b ercorn Street, which was demolished in 1920 to make room for the Lucas Theatre.

Boucher worked in Savannah for 10 years or so, but after inviting free African- A mericans to the ballroom of his house, ran afoul of the city fathers and left. H is pl ace was soon taken by other talented builders and architects, including I s aiah Davenport and William Jay.

Largely fueled by cotton exports, Savannah’s building trade surged for several years after the end of the War of 1812, and Jay’s exquisitely styled mansions and public buildings lent a sense of grandeur and prosperity to the city’s streets and squares. I t all c ame apart, however, after a staggering series of disasters – the Panic of 1819, which sent the national and local economies into the tank; the fire of January of 1820, which devoured some 463 buildings in downtown Savannah; and, the most cruel twist of all, the yellow fever epidemic of 1820, which dragged on from May until October and killed more than a 10th of the city’s population.

But, as it had after the fire of 1796, the city recovered and rebounded, using Oglethorpe’s redoubtable plan as its blueprint.

Sources: Savannah Morning News files; Georgia Historical Society papers and publications; “The Oglethorpe Plan: Enlightenment Design in Savannah and Beyond,” by Thomas D. Wilson; “Savannah in the Time of Peter Tondee,” by Carl Solana Weeks; “Savannah: A History of Her People Since 1733,” by Dr. Preston Russell and Barbara Hines; “On the Rim of the Caribbean: Colonial Georgia and the British Atlantic World,” by Paul M. Pressly; “Savannah Architectural Tours,” by Jonathan E. Stalcup; “John Young Noel,” by David M. McCullough Jr., part of the Savannah Biographies held at the Special Collections of Lane Library of Armstrong State University; www.thempc.org; www.savannah.gov; www.loc.gov. THE IS OLDE

TRULY PIN GEORGIAN

K HOUSE

Architectural Styles Sources: Georgia Historical Society papers and publications; “Architecture of the Old South: Georgia,” by Mills Lane; “American Homes: The Landmark Illustrated Encyclopedia of Domestic Architecture, by Lester Walker; “Primary Sources,” a publication of the Massie Heritage Center, Savannah’s Museum for History and Architecture; “Savannah Architectural Tours,” by Jonathan E. Stalcup; “The Savannah College of Art and Design: Restoration of an Architectural Heritage,” by Connie Capozzola Pinkerton and Maureen Burke; City of Savannah Research Library & Municipal Archives.