67 minute read

Afterword

Chapter 2.

THE PROSE OF THE WORLD

Advertisement

Foucault introduces chapter 2. with an analysis of the representational system up until the end of the sixteenth century. He divides the system into what he calls The Four Similitudes: Convenientia, Aemulatio, Analogy and Sympathy. I use these ‘similitudes’ as a means to describe two stop-frame animations of the night sky.

Convenience

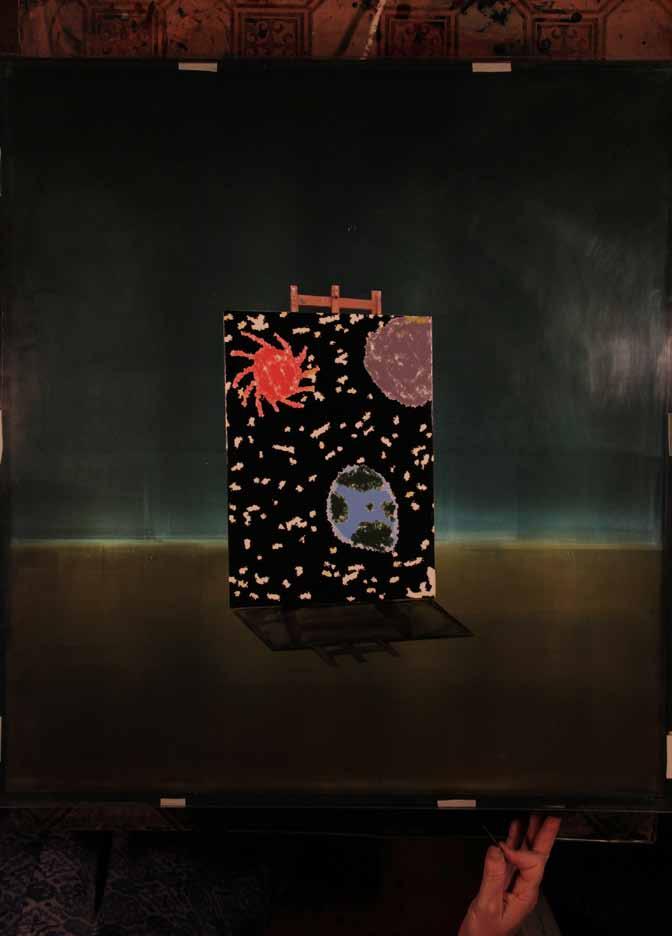

My daughter draws with her nimble finger on her iPad. The sun, the moon, the earth, the stars in the night sky. All of these approximately circular objects are placed in the space of the frame created by the iPad, linked together by digital pixels and the neurons firing like lemon yellow stars in the space of my daughter’s brain.

Emulation

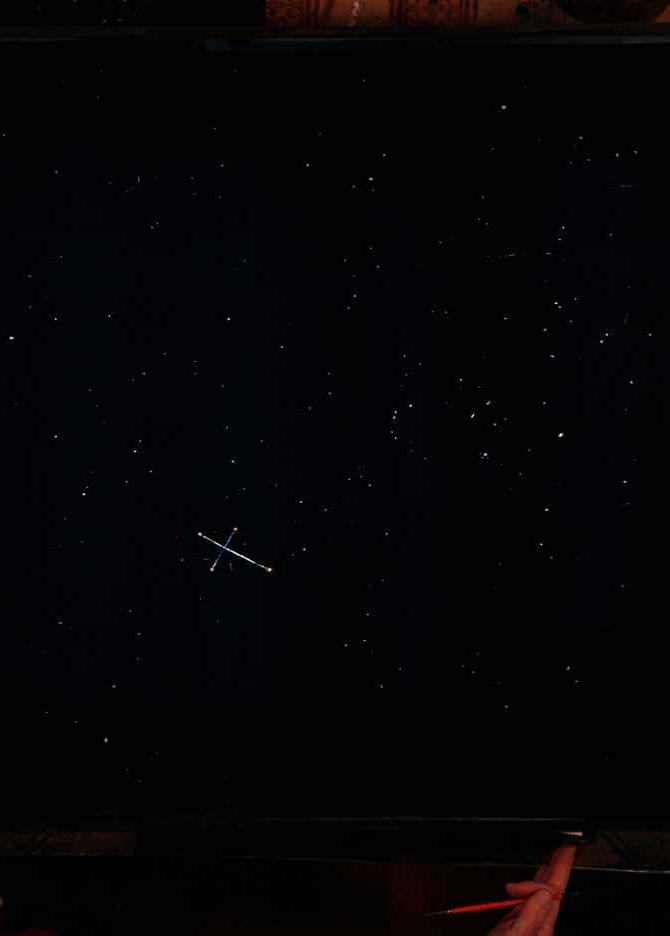

I too create an image of the night sky, an animation depicting the Southern Cross, Night Sky: Southern Cross. My reference is a photograph taken with an app on my daughter’s iPad which reveals the constellation of stars present at a particular moment in the night sky. Originally known by the Latin name Crux, the Southern Cross is a constellation of stars which is only visible south of the equator. It was not observed by people in the northern hemisphere until the Age of Discovery (from the early 15th to early 17th centuries). The first Europeans to observe the constellation were the Portuguese, who mapped it for navigational purposes while rounding the tip of Africa. “Grounded in the history of colonial expansion, it offers a kind of prototypical global positioning system that allows the viewer to know precisely where she stands depending on what she can or cannot see”. [3]

I love my daughter’s digital drawing, our two different but corresponding representational systems of the night sky, and ask her if I can use her image for an animation.

1. Convenientia Things which come close enough together to be in juxtaposition to one another, ‘So that in this hinge between two things a resemblance appears.’ ‘It pertains less to the things themselves than to the world in which they exist. The world is simply the universal ‘convenience of things.’[1]

2. Aemulatio A sort of ‘convenience that has been freed from the law of place and is able to function, without motion, from a distance. There is something in emulation of the reflection and the mirror: it is the means whereby things scattered through the universe can answer one another. [2]

In my studio I create a stop-frame sequence. With a blade I slowly remove the sun, the moon, the earth, the stars, knowing that I am going to reverse this motion, turn time backwards upon itself.

Analogy

There are two stop-frame sequences that cut between each other. The one sequence, Night Sky: Sun, Moon, Earth is of the time-inverted sequence of my daughter’s digital drawing. The other The Princess Paints the Night Sky is of my daughter, in her role as the princess, painting a canvas, set in the Eastern Cape landscape. The princess, as in Las Meninas, is the centre of all attention and it is against her small frame that everything else in the image is measured. In the stop-frame sequence she remains still, it is only her arm that moves up and down, painting. Her arm radiating outwards from her body is like one of the lines she has drawn to describe a ray of fire pulsing out from her sun.

Sympathy

When I look closely at my daughter’s image, I notice that her depiction of the earth looks like a photograph taken from outer space, maybe from a rocket-ship as it draws away from the earth on its way to the moon. It is the earth seen from a distance, the shape of the continents delineated, even an island. Her earth looks untampered with.

The sun is a red ball, with circulating lines that curve around it and suggests movement. This is a sun not drawn from observation, it is a sign she has learnt that stands for sun. The moon is the largest object in the sky. The lemon yellow stars were created by her tapping her small fingers on the iPad screen.

Although the earth, the sun, the moon, have been conceived by her using different constructs of perception, each object takes up almost the same space in her composition. There is also a uniformity of surface which is about the limitations of the digital image, unlike a drawing on paper the objects are not differentiated by the pressure brought to bear of pencil on paper, or of paint soaking into canvas.

3. Analogy In this (older Greek term) analogy, convenientia and aemulatio are superimposed. Like the latter, it makes possible the marvellous confrontation of resemblances across space; but it also speaks, like the former, of adjacencies, of bonds and joints.

The space occupied by analogies is really a space of radiation. Man is surrounded by it on every side; but inversely, he transmits these resemblances back into the world in which he receives them. [4]

4. Sympathies Sympathy is an instance of the Same so strong and so insistent that it will not rest content to be merely one of the forms of likeness; it has the dangerous power of assimilating, of rendering things identical to one another, of mingling them, of causing their identity to disappear – and thus of rendering them foreign to what they were before. [5]

Antipathy maintains the isolation of things and prevents their assimilation; it encloses every species within its impenetrable difference and its propensity to continue being what it is.[6]

Antipathy

My daughter grasps the essence of each of these objects, what differentiates them intrinsically from one another, this is conveyed mainly through colour. The sun is made of fire, it is painted red and orange; the moon is cool, silver grey and crater stippled; the earth is the only object that could have life on it, a pale blue line envelops it like a layer of oxygen, the oceans a cobalt blue, the land a lush meridian green.

These are the colours I attempt to match in the sequence The Princess Paints the Night Sky in which the princess magically levitates into the air, the paint flying off the canvas as she completes her painting of the night sky.

NOTES

[1] M. Foucault, The Order of Things: An Archaeology of the Human Sciences (London, 1970, p. 18). [2] Ibid. p. 19. [3] E. Gabara, Art and Globalization (ed. J. Elkins, Z. Valiavicharska and A. Kim, Pennsylvania, 2010 p. 201). [4] M. Foucault, The Order of Things: An Archaeology of the Human Sciences (London, 1970, p. 21). [5] Ibid. p. 23 [6] Ibid. p. 24.

Chapter 3.

REPRESENTING

Hesitancy

Foucault begins his essay Representing by describing Velásquez at his easel.

The painter is standing a little back from his canvas. He is glancing at his model: perhaps he is considering whether to add some finishing touch, though it is possible that the first stroke has not been made. The skilled hand is suspended in mid-air, arrested in rapt attention on the painter’s gaze; and the gaze in return, waits upon the arrested gesture. [1]

The italics in Foucault’s quote above were inserted by de Diego [2] to point out the hesitancy of the words Foucault uses to describe the process of looking, of painting. It is this quality that pulls my attention to the fragile space that hovers between canvas and brush. Foucault is describing a painting but also seems to emulate the experience of holding a paintbrush.

I find that in the process of making an image, even when the parameters are set, the outcome is always inconclusive, indeterminate. Finality is perhaps possible, but I can never tell for sure. It is about the space between the surface and the mark about to be made, this in-between moment that Foucault captures through language.

Aperture

The aperture of the camera opens and shuts, opens and shuts as I work on the stop-frame sequence Velásquez at Burnt Kraal. My hand and arm move from the image on the light box to the remote, click, click, click, to the ink and the paintbrush, click, click click.

The arm of the paper artist moves up and down up and down, like Don Quixote wielding his sword, the tip of the imaginary paintbrush brushes the fictional canvas in its sweep downwards. The artist, in silhouette, is cut from a section of text from page five of Las Meninas.

I set the artist on fire. Fragments of text are just discernible as it burns away. After the fire, I use my breath, like the puffed up faces of the winds on old maps, to blow away the charred remains of text and canvas. As they drift away the blackened words and image become indistinguishable from one another.

Madrid, 1565

Seventeenth century Spain, in the Hapsburg court of Philip IV places Velásquez “...at the heart of the centralized power structure of one of the original nation-states of early modern Europe, one that was also on the forefront of early modern cultural production.” [3]. The setting for Las Meninas is a room in the Alcazar palace, Madrid. Here in the centre, in the royal chamber, Velásquez paints himself gazing at the king, who is reflected in the mirror. “...the King’s representation is a force or power, a manifestation of royal power that embodies, displays and extends it”. [4]

Paris, 1966

Les Mots et les Choses was published in France in 1966 and went on to become a bestseller there. Four years later this book was published in English as The Order of Things. Foucault in his foreword to the English edition makes a request to his English-speaking reader, “In France, certain half-witted ‘commentators’ persist in labelling me as a ‘structuralist’. I have been unable to get it into their tiny minds that I have used none of the methods, concepts, or key terms that characterize structural analysis. I should be grateful if a more serious public would free me from a connection that certainly does me honour, but that I have not deserved.” [5]

Burnt Kraal, 2014

On the outskirts of Grahamstown is a small area of commonage locally known as Burnt Kraal adjacent to the farm Burnt Kraal which once belonged to Piet Retief. This boer leader settled in the area in 1814 and acquired wealth through livestock farming. In response to cattle raiding parties he led punitive expeditions against Xhosa people living in nearby territories. The name Burnt Kraal is attributed to a fire which kept burning as a result of years of accumulated dung in a cattle kraal. The fire, which is said to have burnt for about ten years, had started before the arrival of the 1820 settlers. [6]

Palimpsest

Velásquez at Burnt Kraal merges an artist, ‘Velásquez’, painting in Madrid in 1565 and a text by Foucault, written in France in the 1960’s. Almost four hundred years apart, Velásquez and Foucault both produced their seminal works in two powerful European cultural centres. In this composite figure the ‘Foucault’ configured ‘Velásquez’ merges the text Las Meninas with the painter of Las Meninas.

Superimposed on a ‘colonial’ landscape, the commonage Burnt Kraal in the Eastern Cape, a place on the frontier, is my ‘Velásquez’. A palimpsest, the Eastern Cape landscape is visible through her transparent text configured body. In the animation the artist on fire evokes the fire that once raged for ten years in the landscape now visible through her burning body.

NOTES

[1] M. Foucault, The Order of Things: An Archaeology of the Human Sciences (London, 1970, p. 3). [2] E. De Diego. Representing Representation, Reading Las Meninas, Again in Velásquez’s Las Meninas, ed. Suzanne L. Stratton-Pruitt, Cambridge, 2003, p. 150). [3] A. Shmitter, Picturing Power: Representation and Las Meninas (Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism 54: 3 Summer, 1996 p. 265). [4] Ibid. p. 266. [5] M. Foucault, The Order of Things: An Archaeology of the Human Sciences (London, 1970, p. xiv). [6] The property was bought by the South African Defense department in the 1970’s as a practice range for the adjoining military base. (Algoa Gazetteer compiled by C.J. Skead, 1993).

Chapter 4.

SPEAKING

The Fine Art and Music Departments of Rhodes University are situated on Somerset Street, Grahamstown. Somerset Street is named after Lord Charles Somerset, British Governor at the Cape from 1814 to1826. It was during his term that the 5th Cape Xhosa War broke out. Grahamstown was named after Colonel John Graham who defined his military career by pushing thousands of amaXhosa residents from the area by what John Cradock, govener of the Cape Colony, called ‘a proper degree of terror’. Rhodes University is named after Cecil John Rhodes, the ultimate embodiment of British Imperialism.

To get from my office in the Fine Art Department to the Music Department I walk down a brick path and over a small bridge. I have a meeting with Lotta Mtambo who teaches singing. The Music Department is built around a small courtyard with offices radiating outwards. It reminds me of a monastery. I wait in in the courtyard for Lotta. Behind her soundproof door I can hear the muffled voice of a man singing. When the door opens, I am shown into an office with sheets of music piled up, and strewn over the floor.

I do not have a musical background and find it hard to articulate what I want the sound to communicate. I realize that all my reference points are visual, I am struggling to bridge the gap of our different disciplines. I show Lotta images that I am working with, hoping this will convey what I want, but I can sense that it doesn’t really help her.

I explain to her how in my narrative, everyone is silent, so it will be only through her voice that the emotion will be conveyed. Lotta sings to me, her voice vibrates in the small office space. She says she can sing with a range of emotions, for example, pure like a young girl. She is Finnish and as she sings I imagine water streaming over rocks in a cold country. She explains that if she keeps her mouth closed and hums that will convey emotion held back, repressed. She hums for me. She also whistles.

The music that I have found that best communicates the mood I want is a Byzantine liturgical chant sung by a choir of male singers. Using this as a guide I have commissioned composer Jared Lang to devise a score for Lotta. He has had to adapt a chant intended for a group of men to a lone female voice.

In the formal space of the Spanish Court, male voices, in particular the voice of the king, predominated. A female voice went unheard, was silent.

The adaptation means that Lotta’s vocal range is stretched to its limit. She is struggling with the low, deep notes. She points to the score and says look here and here, this is impossible! All I see are dancing black circles and lines, I cannot see what she sees, I cannot read this text, she has to translate it for me with her voice.

In addition to Lotta’s voice, I want to integrate sounds of nature into the score. I go out hunting for sounds with my digital recorder.

Dawn December in the Karoo, it is hot already, I lie still and switch the recorder on. I am hoping to capture the sound of the mosquitoes that have been whining in my ear all night, but the recorder only captures the birds twittering.

Noon The air is motionless, dry, I walk to a place where red rocks bake in the sun. The sound of cicadas is shrill and loud, sometimes they stop for a heartbeat and then they start up again. I keep still and switch on the record button.

Night There is a vlei with rushes close to the Owl House in Nieu-Bethesda. Hundreds of frogs are throatily murmuring to each other. It is so dark there but the Milky Way above me is clear, every aperture open. When I play back the sound, I discover that where I only heard frogs, the indiscriminate recorder picked up dogs barking relentlessly in the township across the valley.

Synthesis

I take these recordings to Corinne Cooper’s sound studio. An ex-DJ with tattoos on her arm, Corinne is sensitive to sound, comprehends it. She takes disparate sounds and layers them, manipulates them, she plays with them and describes some sounds as naughty children she needs to bring into line. She is a perfectionist and critical of sounds I cannot hear. Occasionally I can see that she is moved by the way certain sounds come together. She and Lunga Heleni, her assistant, work together. They bicker like familiar colleagues, like a mother and son, and together produce sound that is complex and layered.

On her computer, I watch as she works instinctively with mathematical musical formulas, graphs whose curved lines undulate like waves and blocks of different coloured squares which move in patterns she determines. It is both mathematical and transcendent.

Those graphs and patterns represent the many layers of sound she and Lunga are working with, recordings of Lotta’s voice, singing, humming, whistling, my digital recordings, the synthesizer played by Corinne, edited by Lunga, fire and sea, of San music and drum beats. There is a line on the graph that I take particular note of, it is the line that represents my recording of the cicada’s shrill call. NOTES:

Chapter 5.

CLASSIFYING

Linnaeus

On the right hand side of Las Meninas, placed in a group, are two dwarfs: a disproportionate female dwarf, Maribarola, who has achondroplasia (the most frequent form of short-limbed dwarfism), and a proportionate male dwarf, Nicolasito Pertusato, who is playfully kicking the Spanish mastiff who lies in front of them. In To Be King, I echo this composition, the obscure red smudge of paint in Maribarola’s hand, I transform for my narrative purposes into a red rose.

By placing this group on the periphery of the painting, within a triangular formation, the two dwarfs and dog are reinforced as a category to be placed against the norm. The scrutiny of a new scientific order, characterised by Linneus’s rigid structural system, was first brought to bear on plants and animals. “By limiting and filtering the visible, structure enables it to be translated into language. It permits the visibility of the animal or plant to pass over in its entirety into the discourse that receives it.” [1] This classification system which widened its parameters to include humans, enabled dwarfs to be categorised as other than the norm, and was the foundation for the categorising of racial difference.

In disability studies, we tend to refer to the cameo appearances of disabled persons as prostheses for narrative coherence and closure; the dwarf is not at the centre of the painting because she must support the theme of gendered, national power that is hidden from us but whose position we, as viewers, occupy. Although Las Meninas precedes the usual date for the emergence of biopower, yet we see in the painting’s infinite regress the founding of a world based on a rationalized body. In order to do so, we must be able to distinguish, say, between a dwarf and a girl or a dog; we must understand the categories of humanness that the court reifies into law. In short the grotesque body is foundational for the court body, just as we, as the absent subjects of the painting, replace the King’s body.” [2]

Until the time of Aldrovandi, History was the inextricable and completely unitary fabric of all that was visible of things and of the signs that had been discovered or lodged in them: to write the history of a plant or an animal was as much a matter of describing its elements or organs as of describing the resemblances that could be found in it, the virtues it was thought to possess, the legends and stories with which it had been involved, its place in heraldry, the medicaments that were concocted from its substance, the foods it provided, what the ancients recorded of it, and what travellers might have said of it. The history of a living being was that being in itself, within the whole semantic network that connected it to the world. [3]

Before the taxonomy of Linnaeus, the history of a plant, or animal was inclusive of all its ‘history’ in a system that allowed for connections rather than separation.

In this section, I revert to this older order, I am disordered, I mix up the Linnaen classification system with literature, psychology, anthropology and history to explore ideas around the dog, the rose and the two dwarfs.

The Dog

Dog: Canis lupus familiaris

Breed: Rhodesian Ridgeback/ African Lion dog

On page xv, in the preface to the Order of Things Foucault quotes a ‘certain Chinese encyclopaedia’ in which it is written that animals are divided into: [4]

a.) Belonging to the Emperor b.) Embalmed c.) Tame d.) Sucking pigs e.) Sirens f.) Fabulous g.) Stray dogs h.) Included in the present classification i.) Frenzied j.) Innumerable k.) Drawn with a very fine camelhair brush l.) Et cetera m.) Having just broken the water pitcher n.) That from a long way off look like flies

The Rhodesian Ridgeback presents dog breeders with a classification conundrum, there are presently five competing theories, none of them can agree if the dog is a:

a.) Scenthound b.) Sighthound c.) Cur-dog d.) Wagon dog e.) Ridged primitive

History: (from Wikipedia)

The Rhodesian Ridgeback is a dog breed developed in Southern Africa, Zimbabwe. Its European forebears can be traced to the early pioneers of the Cape Colony of Southern Africa who crossed their dogs with the semi-domesticated, ridged hunting dogs of the Khoikhoi.

In the earlier parts of its history, the Rhodesian Ridgeback has also been known as Van Rooyen’s lion dog – simba inja in Ndebele, shumba imbwa in Shona – because of its ability to keep a lion at bay for long enough to allow its master to kill the lion.[5]

Malaria

Foucault’s seemingly benign description of the Spanish Mastiff lying at the feet of the dwarfs in Las Meninas belies the anxiety created by the indistinct and permeable boundaries suspected to exist between animals and humans. “ An anxious England even made bestiality a capital offense in 1534, lest the occasional, unsettling birth anomalies that suggested hybridity might burgeon uncontrolled as testimonies to some threatening courtship between man and beast.” [7]

If the dog is not intended to be anything but an object than distance can be maintained. The right amount of distance is needed so that the animal can be contained within its proper category.

The origins of the anxiety, “...the ambiguous values assumed by animality”, Foucault argues, stem from the projection onto the animal of its close relationship with death. “...the animal maintains its existence on the frontiers of life and death. Death besieges it on all sides; furthermore, it threatens it also from within, for only the organism can die, and it is from the depth of their lives that death overtakes living beings.” [8]

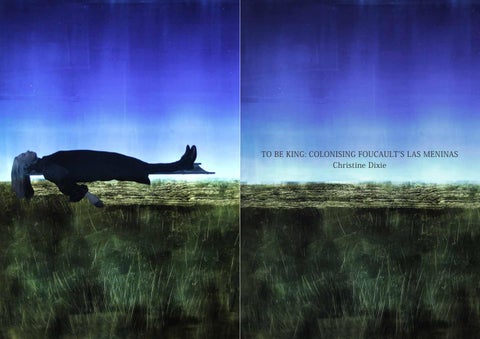

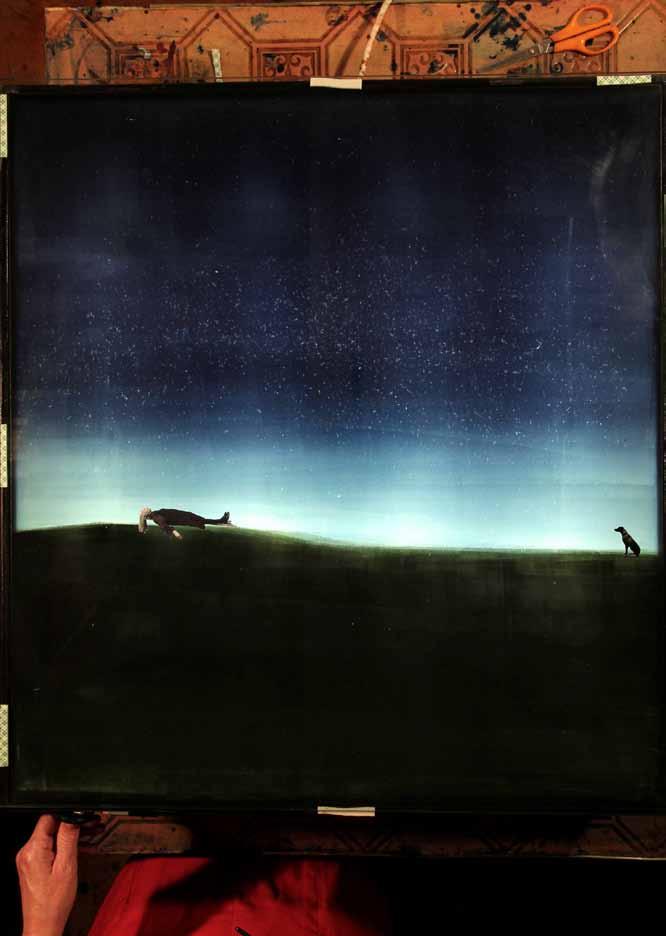

Back in my studio I work on Velásquez with Malaria, in which the role of the painter observing and the dog as docile object are reversed. At the outer reach of the frame, placed to the right, an echo of its placement in Las Meninas, sits a dog in profile. ‘Velaquez’ is lying down on a stretcher, above her is the night sky. Like an explorer into the interior of Africa suffering from malaria, she moves suspended over the landscape, unseen hands carry her along. In her feverish state she is transported along the horizon line. She is passive, prone, observed by a dog who watches her attentively.

… to the right the dog lying on the floor, the only element in the picture that is neither looking at anything nor moving, because it is not intended, with its deep reliefs and the light playing on is silky hair, to be anything but an object to be seen. [6]

The Rose

When I google ‘Rose’ the information on the first page of Wikepedia includes this classification system: [10]

The Rose

According to this order (Linnaen), every chapter dealing with a given animal (and plant) should follow the following plan: name, theory, kind, species, attributes, use, and to conclude, Litteraria. All the language deposited upon things by time is pushed back into the very last category, like a sort of supplement in which discourse is allowed to recount itself and record discoveries, traditions, beliefs, and poetical figures. [9]

The site is structured:

1. Botany 1.1 Species 2. Uses

2.1 Ornamental plants 2.2 Cut flowers

2.3 Perfume

2.4 Food and drink

2.5 Medicine

2.6 Culture

The Birthday

The rose is such a loaded symbol. Of all the flowers it must be the most clichéd. I seriously try to think of other flowers I could use, but I feel compelled to use the rose because of its association with Oscar Wilde’s story of 1891 The Birthday of the Infanta. This tale tells of a heartless young girl, who flirts with the dwarf given to her for her twelfth birthday, giving him a rose from her hair. [11] “Wilde’s story has been read as an attack on aestheticism’s cultivation of surface beauty; the “ugly dwarf” belies a noble soul while the Infanta reveals a superficial glamour.” [12]

The dwarf, who in Wilde’s story is more fully human than the princess, reverses the dominant logic of the Spanish court. Dwarfs in that context were present to reinforce the established ‘order of things’. The hereditary right of the royal lineage was made visible by deliberately placing a misshapen dwarf next to a prince or princess. This coupling was often depicted in dynastic children’s portraits in this era. [13] “ Dwarves and ‘natural fools’, prized at most European courts though nowhere more than in Spain, were often included in their masters’ portraits, to be leant on or petted in the same way as slaves or faithful dogs.” [14]

The rose is associated in Oscar Wilde’s story with his humiliation. In To Be King, the rose, held closely to the dwarf’s heart, stands as a sign of the dwarf’s subjugation. On set in To Be King I as the ‘dwarf’ move (on my knees) with an ungainly gait to centre stage, the place recently occupied by the princess. I/She throws down the rose like a gauntlet, a challenge to the representational system I/she is classified by.

Dwarf 1

Classification: Achondroplasia

Achondroplasia Phenotype Gene relations Location 4 p16,3

Phenotype MIM No. 100800 Phenotype map. Key 3 Gene/Locus FGFR3

Clinical Synopsis

A number sign (#) is used in this entry because achondroplasia (ACH) is caused by heterozygous mutation in the fibreblast growth receptor .3 gene (FGFR3; 134934) on chromosome 4p16.3.

Description

Achrondroplasia is the most frequent form of short-limbed dwarfism. Affected individuals exhibit short stature caused by rhizometic shortening of the limbs, characteristic faces with frontal bossing and midface hypoplasia, exaggerated lumber lordosis, limitations of elbow extension, gene varum, and trident hand. (summary by Bellus et al.1995) [15].

Dwarf 1.

One of the most challenging ethical decisions in To Be King, was how to portray the dwarf Maribarbola. One of the problematic historical projections onto dwarfs is that they were regarded as eternal children. This projection is emphasized when an older dwarf was placed next to a toddler in paintings such as Prince Balthasar Carlos with an Attendant Dwarf (1632) by Velásquez. In this dynastic portrait the toddler is dressed in a captain-general’s uniform while the older dwarf wears a child’s apron. The toddler holds a sword and baton, symbols of his adult status in the monarchy. The dwarf holds an apple and a rattle emphasizing his role as an enduring child. “Baltasar Carlos represents the transcendent monarchic ideal to which, suspending our disbelief, we pledge allegiance; the dwarf is sublunar reality, a malformed and perennial child, subject to sulks and fretfulness, who will never grow up to be king.” [16]

On set I am on my knees again, not in prayer as the mother/angel figure but as the dwarf Maribarola. On my knees, I am the same height as a child. On my knees I see things from a different perspective. To transform myself into Maribarbola I dye my hair brown, which greatly disturbs my daughter. She does not like it that we do not reflect each other, and makes me promise not to ever do it again. I tell her, “I am still the same mom” but she isn’t convinced and she is right. When I unexpectedly catch a glimpse of myself in the mirror I do not recognise myself. I have only dyed my hair, but even this has makes me feel doubled, other.

…the mirror image threatens to draw us into its spell of spectral doubling, annihilating the self it wants to see reflected. At the same time, it gains pleasure from the access it gives to the subject’s exteriority, from an illusory mastery over its image. Fascination with the monstrous is testimony to our tenuous hold on the image of perfection. The freak confirms the viewer as bounded, belonging to a “proper” social category. The viewer’s horror lies in the recognition that this monstrous being is at the heart of his or her own identity, for it is all that must be ejected or abjected from self-image to make the bounded, category-obeying self possible. [17]

In Las Meninas there are many doubled, duplicated figures. The two meninas, dressed almost identically, face each other. There are two Velásquez’s, Diego Velásquez, the one who stays, and José Nieto Velásquez, the one who hesitates on the threshold. There are two dwarfs and two shadowy, indistinct couples, the king and queen, and the couple placed in the middle distance, to the right of the composition.

Apart from its colour, the green blouse and skirt made for my role as Maribarbola, duplicates the red blouse and skirt made for my role as menina. In both roles I am kneeling, in both I am placed next to my daughter who herself is doubled in her roles as princess and dwarf.

Dwarf 2. Classification: Proportionate Dwarf Nicolasito Pertusato

In the Spanish court Maribarbola was perceived as monstrous, her limbs disproportionate to one another. Nicolasito Pertusato, the male dwarf is not monstrous, merely diminutive, yet he is still classified against the norm. “Whether addressing ideas of beauty in nature or works of art, aesthetic judgements presume a normative standard of perception and an ideal of bodily perfection as the object of affective response.” [18]

In To Be King, my daughter dresses up in the white gown of the princess. Dressed in her brown pants and top she also plays the role of the proportionate dwarf, Nicolasito. As she moves between the two roles, she becomes both princess and dwarf, male and female, normal and abnormal, the same and the other.

Dwarfs were perceptively painted by Velásquez, even compassionately, but he was in control of how they were portrayed, he did the looking. [19] In the film shoot, Vision, in which my daughter plays Nicolasito, she controls the gaze by lifting binoculars to her eyes.

Technological inventions such as binoculars which are linked to sight have an ominous presence here in this Eastern Cape landscape as a signifier of what could be possessed. Binoculars which enabled one to look at a space from afar were intrinsic to the new military technology of colonialism. In a previous work, The Great Kei River and Moni’s Kop from the North (1997) I make this connection more explicit. [20]

NOTES

[1] M. Foucault, The Order of Things: An Archaeology of the Human Sciences (London, 1970, p. 135). [2] M. Davidson, The Rage of Caliban: Missing Bodies in Modernist Aesthetics (2013 p. 13). [3] M. Foucault, The Order of Things: An Archaeology of the Human Sciences (London, 1970, p. 129). [4] Ibid (p. xv). [5] en.wikepedia.org/wiki/Rhodesian_Ridgeback [6] M. Foucault, The Order of Things: An Archaeology of the Human Sciences (London, 1970, p. 14). [7] R.Thomson, (ed.) Freakery: Cultural Spectacles of the Extraordinary Body, (New York and London, 1996, p. 2). [8] M. Foucault, The Order of Things: An Archaeology of the Human Sciences (London, 1970, p. 277). [9] M. Foucault, The Order of Things: An Archaeology of the Human Sciences (London, 1970, p. 130). [10] en.wikepedia.org/wiki/rose [11] O. Wilde, 1891 The Birthday of the Infanta in The Complete Shorter Fiction of Oscar Wilde (ed. Isobel Murray, Oxford, 1979). The dwarf falls in love with the girl and, never having seen himself in a mirror, does not realise he only there to amuse her. Rambling around the palace, he accidentally sees himself in a mirror, “a monster, the most grotesque monster he had ever beheld. Not properly shaped, as all other people were, but hunchbacked and crooked-limbed with huge lolling head and mane of black hair”. Despite his anguish, the princess orders the dwarf to continue to dance and entertain her. His heart is broken, and he dies. [12] M. Davidson, The Rage of Caliban: Missing Bodies in Modernist Aesthetics (2013, p. 3). [13] Ibid. The confrontation of Beauty and Beast, princess and dwarf, self and doppelganger, marks the era’s fear of dysgenic “amalgamation” that would result in racial pollution. At the same time, The Birthday of the Infanta advances this fear into the aesthetic realm as a question about the nature of Nature, whether it exists in the mirror of science or is improved in the mirror of art. (p. 8). [14] E. Langmuir, Imagining Childhood. (Yale University 2006, p. 195). [15] www.omim.org/entry/100800 [16] E. Langmuir, Imagining Childhood. (Yale University 2006, p. 196). [17] R.Thomson, (ed.) Freakery: Cultural Spectacles of the Extraordinary Body, (New York and London, 1996, p. 65). [18] M. Davidson, The Rage of Caliban: Missing Bodies in Modernist Aesthetics (2013 p. 2). [19] Ibid. What happens when the dwarf “looks back” and denaturalizes the natural standpoint? An increasingly visible cohort of short statured artists, activists, and performers – Peter Dinklage, Thomas Quastoff, Tom Shakespeare, Corban Walker, Colleen Fraser, Danny Woodburn – are turning the mirror back on viewers, listeners and cultural theorists. Instead of occupying the margins of classical paintings – as decorative or architectural elements of court portraits – they occupy centre stage as actors, vocalists, sculptors, and disability theorists, who subject mimesis to a different optic. (p. 22) [20] M. Godby, The Lie of the Land: Representations of the South African Landscape. (Cape Town, 2010). “Christine Dixie has recently draw attention to the imperialist strategy of the high viewpoint in The Great Kei by including in the first plane of her engraving a figure looking over the temporary frontier of Xhosa independence effectively as the first act of appropriation of a new territory.” (p.112).

A Virtual Child Chapter 6.

EXCHANGING

The image of the Infanta Margarita is at the centre of the painting in terms of composition and lighting. But, Lacan claims, that image which most captures our attention is an imaginary image, constituted by reflections.

“In place of his object, the painter, in this work, in this object that he produces for us, has placed something which is made of the Other, of this blind vision which is that of the Other, in so far as it supports this other object. This central object, the split, the little girl = phallus, which is what, moreover, I earlier designated for you as the slit.” [1]

“…in the centre of this picture is the hidden object” writes Lacan. It is the (Lacanian) slit beneath the Infanta’s dress which foregrounds her in the painting as an object of exchange. Velásquez had already painted three official portraits of the Infanta between 1653 and 1656, the subsequent depiction of Maria Therese’s young five year old body in Las Meninas, also in 1656, was part of the intricate political machinations of extending political power through marriage.

As an object to exchange in return for political advantage, the Infanta, depicted in the painting exists as a phantasmic projection. In this sense, the Infanta is a virtual image, a consequence of the exchange of gazes between the viewer and the reflection of the royal couple in the mirror. [2]

In the video projection of To Be King, this interpretation of the child only being there as a result of the gaze, constituted by desire, in effect a virtual child, is given further emphasis through the medium of film in which the child’s body is literally a projection of light and shadows.

The focus on the mirror is the point at which Foucault essay on representation and Lacan’s theory on the formation of the ego intersect, De Diego notes, “Once again, and as it was in Foucault, the reflected king is the basic clue for Lacan: His very presence as Other guarantees the completeness of the painting.” [3]

The mirror in Las Meninas, both in the essay and the painting, is the central axis around which text and image circulate. In a series of seminars on Las Meninas, delivered in 1966, Jacques Lacan focussed on this painting as a way of introducing some of the complex spatial aspects of the mirrorstage in the formation of the Self to his psychoanalyst students.

The Mirror/ The Screen/ The Frame

The framed screen in To Be King, quotes through scale and style the framed painting Las Meninas hanging in the Prado Museum. However, within the sequences that make up the video component of the installation another frame is quoted, that of the mirror within the painting. It is in the video sequences that depict the king’s deposition that the frame of the painting is replaced with the frame of the mirror as the ‘mirror’ is enlarged to fit the screen.

But there are other moments within the video sequence in which the screen becomes the mirror in another sense, these are the moments in which the Princess stands alone on set and looks out at her double, The Black Infanta, It is these instances which mostly clearly visualize the psyche’s formation of the ego and the dialectical relationship between the subject and the object as articulated by Lacan in the mirror-stage. Slovaj Zizek explains:

Yet facing the mirror/painting within the installation, in the space where the ‘animated’ subject would be is yet another immobilized figure, The Black Infanta.

The space between the two Infanta’s, is the space of desire, crucial in the formation of subjectivity. Recognising the Other in the mirror, marks the moment of acquiring language, “We as linguistic beings, are condemned to lack – and therefor to desire – simply because we are condemned to becoming linguistic beings’ writes de Diego. [5]

In his chapter Exchanging, Foucault portrays Marquis de Sade, whose characters epitomize the limits of desire, as exemplifying the moment of the decline of the Classical age. The first section of his book and the chapter ends disconsolately:

At the level of the Imaginary, Lacan – as is well known – locates the emergence of the ego in the gesture of the precipitous identification with the external, alienated mirror-image which provides the idealized unity of the Self as opposed to the child’s actual helplessness and lack of co-ordination. The feature to be emphasized here is that we are dealing with a kind of ‘freeze of time’: the flow of life is suspended, the Real of the dynamic living process is replaced by a ‘dead’, immobilized image – Lacan himself uses the metaphor of the cinema projection, and compares the ego to the fixed image which the spectator perceives when the reel gets jammed. [4]

Sade attains the end of Classical discourse and thought. He holds sway precisely upon their frontier. After him, violence, life and death, desire, and sexuality will extend, below the level of representation, an immense expanse of shade which we are now attempting to recover, as far as we can, in our discourse, in our freedom, in our thought. But our thought is so brief, our freedom so enslaved, our discourse so repetitive, that we must face the fact that that expanse of shade below is really a bottomless sea. [6]

NOTES

[1[ J. Lacan, Ecrits, A selection, “The mirror stage as formative of the function of the I as revealed in the psychoanalytic experience”, ( trans. Alan Sheridan Tavistock publications, 1966 p.284) [2] E. Biberman, On Narrativity in the Visual Field: A Psychoanalytic View of Velásquez’s “Las Meninas”, Narrative, Vol.14. No 3 (Oct.2006), Ohio State University Press,p.250) [3] E. De Diego. Representing Representation, Reading Las Meninas, Again in Velásquez’s Las Meninas, ed. Suzanne L. Stratton-Pruitt, Cambridge, 2003, p.163). [4] S. Žižek, The Plague of Fantasies, (Verso, London, 1997 p.94) [5] E. De Diego. Representing Representation, Reading Las Meninas, Again in Velásquez’s Las Meninas, ed. Suzanne L. Stratton-Pruitt, Cambridge, 2003, p.161). [6] M. Foucault, The Order of Things: An Archaeology of the Human Sciences (London, 1970, p. 21).

PART II Chapter 7.

THE LIMITS OF REPRESENTATION

Surface: The light-table

The glittering, horizontal surface of the light table I work on is lit from below with fluorescent lights. The wooden box which holds the plate of glass was made for me at the workshop at Fort England Psychiatric Hospital. Originally called the Grahamstown Lunatic Asylum, the hospital began as a barracks for the Cape Regiment in 1814 and was converted to a fort during the Sixth Frontier War in 1835. It was one of a chain of forts built along the Eastern Frontier to curb Xhosa incursion into British occupied territory .[1]

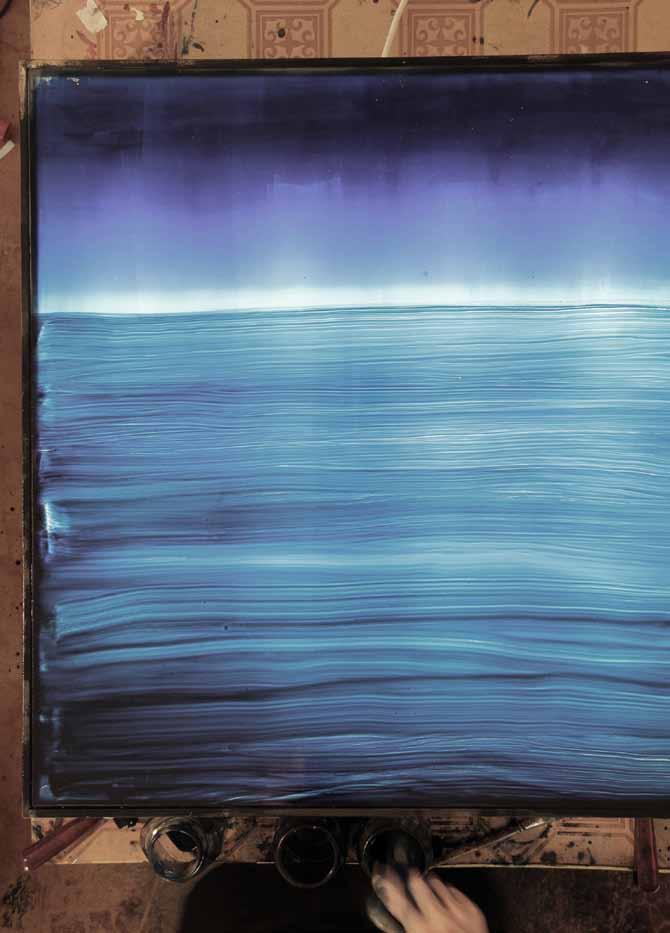

I work over the light-box in my studio. The sequence I am working on requires a lot of slippery ink to mimic the waves of the sea as they roll across the glass table, the ink seeps down the crack between the glass and the frame, dripping over the side, leaving inky stains on the sides of the box, spilling onto the studio floor.

When things cannot be represented by the surface, by the visible signs they present to the world, a radical change in perception takes place. The links between things, say a fort and a hospital reside not on their exterior façade but on a structure that cannot be perceived, is interior to the object. “The conditions of these links resides henceforth outside representation, beyond its immediate visibility, in a sort of behind-the-scenes world even deeper and more dense than representation itself.” [2]

Depth: The Willow Stick

On the outskirts of Grahamstown is a farm owned by Adrian Moss. On a clear winter’s day Jan Nell and I drive there in his bakkie. Jan Nell has lived in and around Grahamstown most of his life, as did his father before him. For a while he lived on this farm but left when he came home to find the house which he had been renting, ransacked.

Although there are willow trees growing abundantly on the land just behind the gate we pass through, the protocol is to first ask permission from the farmer so that we do not arouse suspicion. We drive up to a heavily secured farmhouse with high electric fencing and dogs bark at us from behind the padlocked gate. The farmer’s wife, whom Jan knows, eventually appears and she and Jan greet each other and he asks for permission to uproot trees on my behalf.

We drive back to the willow trees and start pulling them out the ground, I need the whole root intact, I recognise the one I will use almost immediately as I pull it out the ground. Jan chops away the excess branches and we put the sticks in the bakkie and drive back to Grahamstown.

My sculpture The Black Infanta is waiting with her arm extended, her hand enclosed around a gap, an absence, waiting for the willow stick. The stick is inverted so that the root reaches upwards, it is gnarled in contrast to the smooth surface of the sculpture and curves inwards to echo her face. Her pose imitates that of seventeenth century paintings of dynastic male children. The child in these portraits often holds a sceptre, orb or sword, a manufactured sign of the power that he is to yield in the future. The Black Infanta holds before her an Acacia longifolia, more commonly known here as a Port Jackson willow.

In European folklore the willow stick is associated with divining, with witchery, with dark streams underground. Acacia longifolia is more like a cousin to the European willow, but it also likes water, likes the dark underground streams.

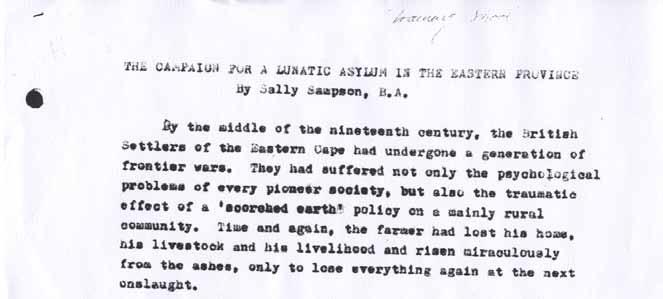

NOTES

[1] S. Sampson, The Campaign for a Lunatic Asylum in the Eastern Cape (undated typescript) [2] M. Foucault, The Order of Things: An Archaeology of the Human Sciences (London, 1970, p. 211).

Chapter 8.

LIFE, LABOUR, LANGUAGE

Language

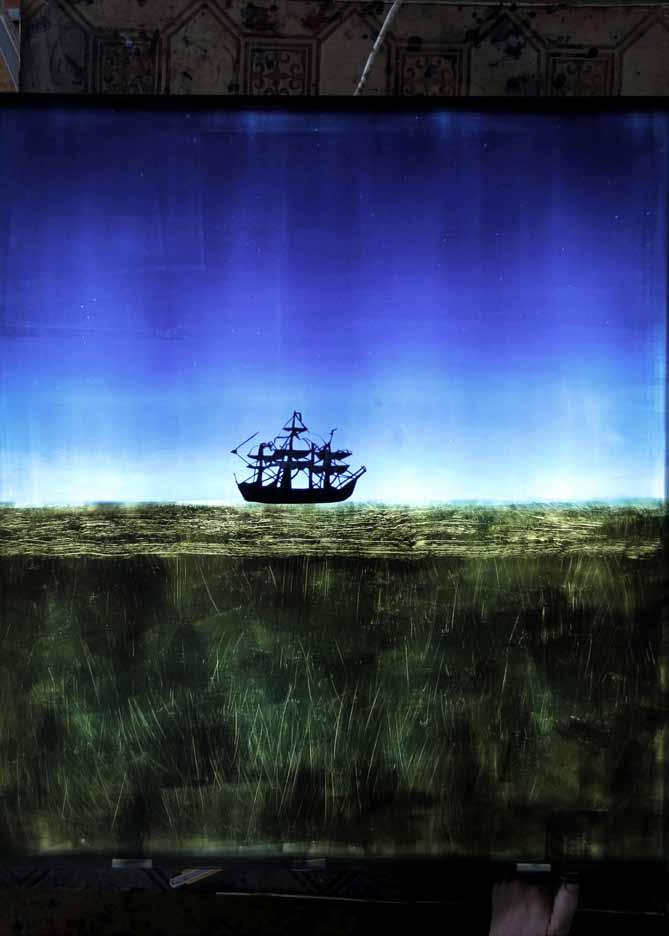

In my studio I roll out blue ink onto the glittering horizontal glass surface of the light box. Two blues, one light, one dark, the point at which they meet becomes a horizon line. Like reading a sentence from left to right, word, by word, I move a ship through time, across the horizon line, until it reaches the vertical limit of the box and falls off the edge.

Contained within a rectangular format, reading text on a page and ordering an object across the surface of a light-box take place across space and in time. There is a particular logic that needs to be taken into account, there are limitations to the directions a paper ship can move across a flat plane and a necessary amount of images needed to create the illusion of continuous motion.

Labour

In Spain during the 16th and 17th century, artists did not have high social standing, painting being regarded as a manual trade, and paintings classified as ‘manufactured goods’ along with clothing, shoes and barrels. Velásquez looking out at the viewer from behind his easel deliberately placed himself in the role of an ‘artist at work’. In his essay, The Meaning of Las Meninas, Jonathan Brown argues that the major impetus behind this large-scale work was Velásquez’s quest for nobility and the challenge to the Spanish establishment that perceived painting as a manual trade. [1]

On the set I carefully paint a moustache and heavy eyebrows onto my face and stand in a pose as close as I can get to that of Velásquez standing in front of his canvas. I don’t hold a palette in my hand as he does: instead I hold a mirror which serves for a palette. The ‘paint’ I place on the mirror/ palette is mascara.

I have taken off the red skirt which I wore in my role as a menina and put on a brown doublet. I wear this doublet over the red menina blouse. After I have put on my moustache and eyebrows, I wipe off the lipstick from my mouth using my fingers, and with the residue lipstick make the mark of the cross on my doublet.

The story goes that the Santiago cross, one of the most prestigious aristocratic military orders of Spain, was superimposed on Velásquez’s doublet ( in the painting) on the king’s orders, after the painter’s death. Ironically for a sign for the legitimization of painting, the cross has violent origins, emulating the sword that decapitated St. James. (2) The posthumous cross on the doublet signified, according to Brown, the main impetus driving the painting of Las Meninas. Velásquez, Brown writes, desperate for promotion to knighthood “lavished the last ounce of his genius upon it.” [3]

Life

My daughter is bored and has come looking for entertainment, distraction. I am in the middle of a delicate stop-frame animation take, I need to work fairly quickly or else the ink, heated from below by fluorescent lights, will dry.

I ask her to sit next to me at the light table where I am working, I have to make sure her shadow doesn’t fall across the image.

I tell her, “Each time I move the ship you need to press this button to make the camera take a photo”. We start to find a rhythm, in her eagerness sometimes she presses the remote before I am ready.

But mostly it works. In this rare moment, my labours of artist and mother come together.

NOTES

[1] J. Brown, Images and Ideas in Seventeenth-Century Spanish Painting (New Jersey, 1978, p. 196). [2] http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Order_of_Santiago, The Order’s insignia is a red cross simulating a sword with the shape of a Fleurs de Lis on the hilt and arms. The three Fleur de Lis represent the “honour without stain”, which is in reference to the moral features of the Apostle St. James’s character. [3] J. Brown, Images and Ideas in Seventeenth-Century Spanish Painting (New Jersey, 1978, p. 196).

Christine Dixie

Chapter 9.

MAN AND HIS DOUBLES

It is only in this chapter, towards the end of The Order of Things, that Foucault refers back to Las Meninas and the place of the king in the order of things.

The Black Infanta: (In) The place of the king

In Las Meninas all vectors point outwards to the space finally reserved for the spectator, in all her corporeality, standing in front of the painting.

Foucault describes an imagined moment in which all the figures (the model, the painter, the king, the spectator) ‘suddenly stopped their imperceptible dance, immobilised into one substantial figure, and demanded that the entire space of representation should at last be related to one corporeal gaze.’[2]

In To Be King, The Black Infanta standing in the space reserved for the king/spectator denies that corporeality. She imitates life, but is dead, made of resin, cloth and wood. She holds the trace of corporeality – the cast, which for a moment in space and time held my daughters face, but she remains an imitation, pointing to, rather than embodying actual existence.

The Black Infanta is made of dead matter but she displaces space, and carries the weight and trace of the history of her making. She stands directly in front of the screen. A young girl in a black dress, she is standing on an enlarged headrest, a place to rest one’s head while dreaming. She is holding a willow stick in front of her, the root pulled from the Eastern Cape earth, the surface, now inverted. Each element of the sculpture is black, like an embodied shadow. The viewer can only see The Black Infanta from the light thrown out by the screen that plays across her features, sometimes she can be seen quite clearly but at other times when the light on the screen is subdued and she disappears back into the darkness.

Man appears in his ambiguous position as an object of knowledge and as a subject that knows: enslaved sovereign, observed spectator, he appears in the place belonging to the king, which was assigned to him in advance by Las Meninas, but from which so far his real presence has for so long been excluded. [1]

Actual experience... does indeed provide a means of communication between the space of the body and the time of culture, between the determination of nature and the weight of history, but only on condition that the body, and, through it, nature, should first be posited in the experience of an irreducible spatiality, and that culture, the carrier of history, should be experienced first of all in the immediacy of its sedimented significations. [3]

The unthought (whatever name we give it) is not lodged in man like a shrivelled up nature or a stratified history; it is, in relation to man, the Other: the Other that is not only a brother but a twin, born, not of man, nor in man, but beside him and at the same time, in an identical newness, in an unavoidable duality. [4]

The Black Infanta and the King exist in the same space. She is both the Other – young, dark, peripheral, powerless and the Same. What does she/we see when looking at the mirror that reflects her/us?

What does she/we find in the place where her/our image should be? She/we find the king, or in other words, the Other, the necessary Other that the Self needs to be completed, the indispensable Other that the Self needs in order to acquire the consciousness of her/our existence. (I have replace he/she in the quote with she/we) [5]

NOTES

[1] M. Foucault, The Order of Things: An Archaeology of the Human Sciences (London, 1970, p. 312). [2] Ibid (p. 312). [3] Ibid (p. 321). [4] Ibid (p. 326). [5] E. De Diego. Representing Representation, Reading Las Meninas, Again in Velásquez’s Las Meninas, ed. Suzanne L. Stratton-Pruitt, Cambridge, 2003, p.152).

Chapter 10.

THE HUMAN SCIENCES

The painting Las Meninas in named for the two meninas – maids of honour. The word menina is not of Spanish, but of Portuguese, origin. It was used to designate the most beautiful young maidens of the old Spanish nobility who were appointed as maids of honour to the Queen of Spain and the princesses at court. [1]

The princess stands at the centre of the painting. On either side of her is a menina, both are dressed in white with dark hooped skirts, both have white trimmings in their short dark hair. The two meninas mirror one another, as if the princess were a looking glass into which they gaze.

Menina 1.

In To Be King, I enact the one menina, Monica Nkombisa the other. These roles mirror each in the painting, and are echoed in our daily lives. Both Monica and I, in our different ways, are there to serve the princess.

The princess is dressed in her white gown, virginal, pure like a lily, yet in the painting there are five stains of red that enclose her. In a diagonal line are three red corsages, one near her hand, one on her chest and one in her hair. On the left, near her right hand is the red bucaro, and on her left shoulder a flash of red stains her hair.

The marriage of the royal princess ensured the reunification of Spain with the Empire. At the age of fifteen she was married to her cousin-uncle Emperor Leopold I of Habsburg. To the Infanta Margarita’s left “Like a donor in prayer, like an angel greeting the Virgin, a maid of honour on her knees is stretching out her hands towards the princess.” [2]

The angel of the annunciation is the embodiment of an idea, an announcement, a figure who is not of this world but a portent of blood that is to be spilled in the future, in this world. The arrival of the angel into the Virgin’s life signals a transformation from one state into another, child into adult, girl into mother – a transitional moment.

I am the mother of the girl child who enacts the princess, yet kneeling beside her, I am also the annunciating angel in the form of the menina, Dona Maria Augustina Sarmiento. Unlike the angel who traditionally holds white lilies in his hand, I, angel-mother-menina, hold out a glass jug which contains dark liquid. In Las Meninas Dona Maria holds out a jug, a bucaro which in Spanish means a type of scented, reddish earth.

In the shoot, Menina Greeting the Princess, the spaces of the royal court and the colony collapse as the liquid poured in the one space falls into the other. The rituals of initiation, marriage and the possession of land, of earth, are enacted between mother and daughter, angel and Virgin, as the liquid drips down the young girl’s mouth and chin and seeps into the stony ground at Burnt Kraal.

Menina 2.

In the video projection, Monica Nkombisa who enacts Isabel de Velasco, the second Menina, is brushing the princess’s long blonde hair. Although we cannot hear her voice she sings a Xhosa lullaby as she rhythmically brushes the princess’s hair. [3]

Monica Nkombisa is the only black person represented in the video/animation narrative. This echoes the practice within seventeenth century European paintings of domestic households in which black servants first started being incorporated into these settings. Not only is there an increased visibility of imagery of black people as servants but “The tensions between the black servant and as exotic object and as a source of slave labour explode with the seventeenth century’[4] In the urban centres of Spain, particularly in Seville but also in Madrid, the presence of black slaves had become naturalized. In Imperial Spain, according to Antonio Dominiguez Ortez, slavery was essentially an urban and domestic phenomenon. “...the ownership and display of slaves in Spain signified the high social status of the nobility and indeed the middle class who required large retinues of servants.”[5]

Peter Erikson in writing about the standard conventions in depictions of black servants in the Northern hemisphere writes of these Renaissance paintings, “In relatively simple cases, the relation between the centre and the margin is unmistakeably clear: the status of the black figure remains firmly locked in its marginal position.” [6].

Within the narrative of To Be King, Isabel de Velasco, played by Monica Nkombisa moves from the role of a servant on the periphery, to centre stage as she holds the gaze of the viewer in a close up shot. Within the animation sequence of the video component it is the sequence in which the king’s head is decapitated and replaced with the head of Isabel de Velasco that a climactic moment of the narrative is reached as the sound increases in pitch, volume and complexity.

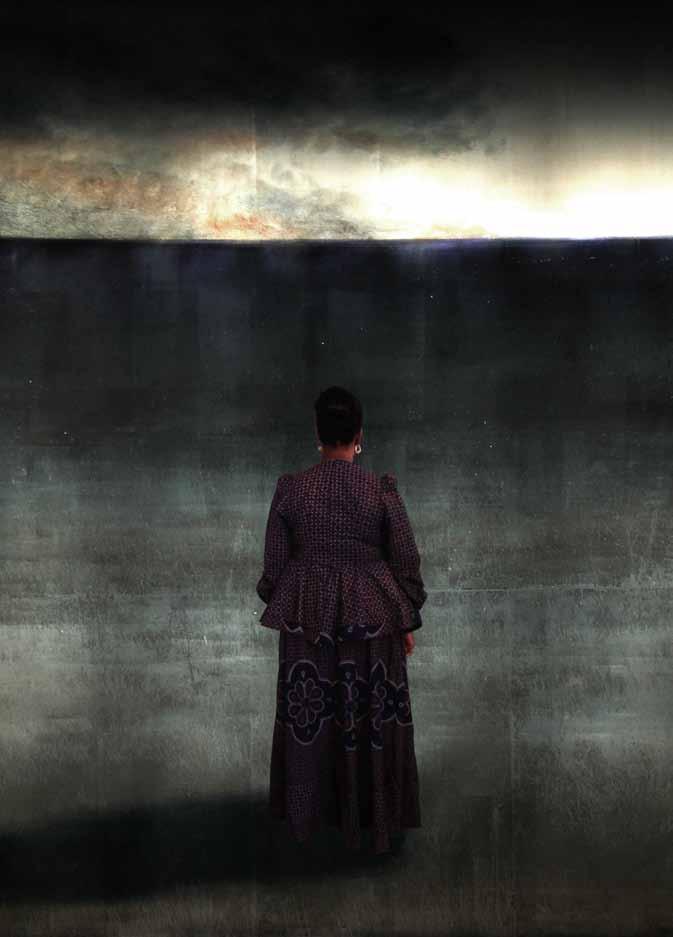

In another animation sequence, Monica Nkombisa stands with her back to the viewer looking out at the burning landscape in front of her, it is the landscape of Burnt Kraal again, a portion of land that was said to have burned for ten years. The violence of the fire that burnt here echoes the violence that has taken place on the frontier land of the Eastern Cape.

Trade Ship

Foucault ends The Order of Things with a section entitled Psychoanalysis and Ethnology. He indicates that he perceives these two ‘sciences’ as potentially offering more far-reaching interpretations of life, language and labour than those of the other human sciences such as psychology, sociology and cultural history.

On Psychoanalysis Foucault writes:

On Ethnology Foucault writes:

In the seventeenth century the way in which European thought was brought face to face with other cultures was through slavery. In the sequence Trade Ship I use a ship from a painting called La Rochelle Slave Ship Le Saphir. [9] I chose it because of its connection with the age of discovery, the age of enlightenment. Spain was a leading naval power at the time Velásquez was painting Las Meninas. King Philip IV, the shadowy figure in the mirror, was implicated in the exploitation that was taking place in the colonies.

Carmen Fracchia writes:

The slave ship, Le Saphir makes a beautiful silhouette, with delicate lines from the mast to the bow. In the animation sequence, Across the Atlantic I take the cut-out ship and sail it across the edge of the horizon line, at the edge of the sea.

In setting itself the task of making the discourse of the unconscious speak through consciousness, psychoanalysis is advancing in the direction of that fundamental region in which the relations of representation and finitude come into play. [7]

Ethnology can assume its proper dimension only within the historical sovereignty – always restrained, but always present – of European thought and the relation that can bring it face to face with all other cultures as well as with itself. [8]

The presence of black slaves in the main urban centres of Imperial Spain and in New Spain was the direct consequence of the practice of Atlantic slavery and the subsequent commodification of the slave from the fifteenth century onwards. The creation of trade licences or monopoly contracts by the crown turned the business of trade into a profitable system, which financed the first Atlantic voyages. [10]

In Conclusion

In my studio, I turn on my light box and superimpose the images of two girls, the one is of my daughter, the other is Maria Theresa, the daughter of the King and Queen of Spain. Light from below, from the depth of the box, illuminates the images, making them transparent. The process of laying one image over another emphasizes the shift in registration, where the edges are the same and where they are different.

One striking difference is that my daughter stands alone in the space, she is not surrounded by an entourage of meninas, dwarfs, court officials and a painter. The presence of these figures alert us to the placement of the Spanish princess at the centre of power and attest to her assumed hereditary right. “...she is a princess, but at the same time a little girl; she is most marvellously self-possessed in bearing, but is herself possessed by the court and by the royal lineage marked by her placement just below her parents’ mirrored image.” [11]

Another difference is that the Spanish princess is motionless, held in paint, rooted to the gaze of her parents. Whereas my daughter, enabled by the medium of film, moves. Unlike the Princess, forever held in place by her lavish dress with restraining hoops below, [12] my daughter constantly shifts between dwarf and princess, male and female, reversing the logic of a stable order offered by a Western inheritance.

What remains the same are the power structures that still organize sight and representation. The king might have moved from the royal palace in Madrid into the White House or penthouse of a central bank, but he still remains in control, his power emanates outwards, announcing a particular vision of the world.

Yet it is in the places where the images do not comfortably overlap that a space emerges, a space for my imagination to slide in and play with the possibility of shifting (however modestly) the order of things.

Thus, between the already ‘encoded’ eye and reflexive knowledge there is a middle region which liberates order itself: it is here that it appears, according to the culture and the age in question, continuous and graduated or discontinuous and piecemeal, linked to space or constituted anew at each instant by the driving force of time,...[13]

NOTES

[1] M. Carminati, Velásquez: Las Meninas. (Milan: 24 ORE 2011 p. 25). [2] M. Foucault, The Order of Things: An Archaeology of the Human Sciences (London, 1970, p. 211). [3] Thula thul’, thula baba, thula sana, Thul’ubab’ uzofika, ekuseni Kukhon’ inkanyezi, eholo’ ubaba, Ekhanyisela indlel’ eziy’ ekhaya, Sobe sikhona Xa bonke bashoyo, Bethi buyela ubeye le’ khanya, Thula thula thula baba

Thula thula thula sana

[4] P. Erickson, ‘Invisibility Speaks: Servants and Portraits in Early Modern Visual Culture Journal for Early Modern Cultural Studies, Vol 9. No1 (Spring-Summer, 2009 Published by University of Pennsylvania Press. (p.33) [5] A Dominguez Ortez, The Golden Age of Spain: 1516 – 1659, London, 1971 p.163 [6] P. Erickson, ‘Invisibility Speaks: Servants and Portraits in Early Modern Visual Culture Journal for Early Modern Cultural Studies, Vol 9. No1 (Spring-Summer, 2009 Published by University of Pennsylvania Press. (p.36) [7] M. Foucault, The Order of Things: An Archaeology of the Human Sciences (London, 1970, p. 312). [8] Ibid. p. 314 [9] H. Isham, Image of the Sea: Oceanic Consciousness in the Romantic Century. (Bern, 2004, p. 22). ‘Ex voto’ refers to a painting commemorating the rescue, or salvation, at sea of someone who had vowed, before embarking on a dangerous sea voyage, to give thanks for his or her safe arrival: the depiction is usually of the specific disaster survived through the help of Jesus, the Virgin Mary, St. Christopher, or some other source of Christian salvation. [10] C Fraccia, ‘The Urban Slave in Spain and New Spain’, 2012, (p.195) [11] S. Alpers, Interpretation without Representation, or, The Viewing of Las Meninas, Representations I (February, 1983, p. 39). [12] M. Foucault, The Order of Things: An Archaeology of the Human Sciences (London, 1970, p. 312).

The Visual Field and the Place of the King By James Sey

The contribution of Michel Foucault’s work to an understanding of the constitution, practices, techniques and objects of the field of the human sciences is well-known and hugely influential. It is also the case that most scholarship which deploys or critiques his oeuvre tends to focus on his so-called ‘genealogical’ work, one of the most popular of which is his book on the institution of the prison, Discipline and Punish (1977a). It is here that the subsequently widespread trope of surveillance is perhaps most clearly broached, one that has since become shorthand for various critiques of our contemporary ‘surveillance culture’.

It is perhaps surprising then that Foucault’s major ‘archaeological’ works contain few extended discussions of any single work of visual art, as an exemplar of the field of a putative visual culture. The major exception of course is his dissection of Velasquez’s canonical painting Las Meninas (1656) which forms the preamble to The Order of Things (1973). This meditation establishes a kind of template for the analyses which follow on the mutations and transformations in the fields of ‘life, labour and language’ that make up the book. Interestingly, the template is that of a visual field, of perhaps the representative visual field for knowledge and power, one in which socio-political power and a new sense of psychological subjectivity are mapped onto a set of relational visual perspectives.

The template is taken up, atomised and explored by Christine Dixie’s recent multimedia video installation work To Be King (2014), in which the artist restages the original Velasquez painting through the lens of the Foucault reading. What Dixie enacts in this work is the possibility of a kind of historically-charged and explicitly post-colonial reworking of an art historical reading of the Velasquez painting. This reworking takes place in the context of a post-Foucauldian and globalised visual culture – and especially in a South African context - in which the particular properties and insights of the work of art itself are subsumed by the proliferation of an image culture which even Foucault himself could not perhaps foresee.

What is particularly unusual and exciting about Dixie’s work is this elliptical and dense visual engagement not only with Velásquez’s canonical work, but with the even more recondite philosophical essay it inspired. At the core of one’s experience of To Be King is the multi-layered video installation. Its seductive textures, a mix of painterly stop-motion animation, video collage and filmed footage, along with its staging as a museum installation, beg many questions. Chief among them is that of making an aesthetic response to a work of hermeneutic philosophy. This is an incredibly audacious move. Dixie, in atomising the original work in ways that remain true to the art historical context of it while elaborating artistically on the (much wider) themes of Foucault’s meditation, goes some way to creating a new form at the interzone between art theory and artistic practice. The work, from one perspective, offers a deeply inventive visual engagement with the historical context against which the original painting was realised – most importantly the appropriative and ideological role played by an artistic gaze able to lay out and reproduce vectors of knowledge and power. From the Foucauldian perspective it offers a ritualised and almost arcane visual template in the terms of which the wider ideas in The Order of Things are picked open and examined from a post-colonial perspective. But how has the artist done so? What in the philosopher’s oeuvre makes it possible, and

how can it be thus transposed from the Western European ‘Classical’ to the perpetually reimagined ‘hinterland’ of a post-colonial ‘frontier’ zone in the Eastern Cape?

As is by now well known, the basic subject matter of Foucault’s genealogical works, most famously Discipline and Punish (1977a), concerns a reversal in the axis of power from ascending to descending; in other words, a shift from feudal regimes in which individuation is greatest where power or privilege operate to modem disciplinary societies - where by contrast it is those upon whom power is exercised, rather than those who exercise it, that are most individualised.

As a result those who vary from or who appear to flout the norm acquire focus and interest, a density and specificity that makes them prime subjects for knowledge as well as the most valued subject matter for discourse.

In “The Fathers No” Foucault (1977b: 194) writes:

... the passage ... from the noble deed to the secret singularity, from long exiles to the internal search for childhood, from combats to fantasies is also inscribed in the formation of a disciplinary society. The adventure of our childhood no longer finds expression in the Le Bon Petit Henri, but in the misfortunes of Little Hans. The Romance of the Rose is written today by Mary Barnes. In the place of Lancelot, we have Judge Schreber ... the psychological in our culture is the negation of epic perceptions.

The typically elliptical and elegant final proposition in this passage emphasizes the point that, in the modem era, the position of centrality previously occupied by the epic hero is now filled by nonheroic and especially fallible individuals.

In Discipline and Punish (1977a), Foucault demonstrates that the shift from societies of spectacle and punishment to modem disciplinary societies is characterised by a shift from external to internal power. In other words, he suggests that power operated in feudal societies as direct punishment imposed on the body of the offender, while disciplinary societies concentrate their energies on the production of subjects of a certain type, ideally those capable of policing themselves.

Crucially in order to enact the high measure of self-control required, individuals are now enjoined to see themselves as constantly falling away, not so much from God or the sovereign but from their selves - those selves to which ultimate allegiance is owed. That to which modem individuals are instructed to be constantly vigilant, is therefore not an outside principle or authority but one (necessarily potentially flawed) apparently safely housed within. Surprisingly, given the centrality of its ‘psychological perception’, the modem individual needs to value no particular psychological content except the possession of a unique self and the belief that this self is, and must be, his or her own to cultivate and maintain.

The Order of Things (1973) underpins the argument of Discipline and Punish (1977a) by analysing the basic reorganisation of the epistemic field characteristic of the modem episteme. More especially, Foucault sees modernity as best explained in terms of the decline or failure of representation, which served as the overall figure in the preceding or ‘classical’ period - a shift which he describes as culminating in “the withdrawal of knowledge and thought outside the space of representation” (Foucault, 1973:242). He argues that Kant’s critique of representation both prefigures, and is symptomatic of, the dispersion of the epistemic field into empirical enquiry on the one hand, and mathematical and philosophical enquiry on the other. The fact that representation was once taken for granted as the spontaneous means whereby subject and object are related is reflected in the fact that as soon as representation is problematised in the nascent modem episteme the problem of the subject/object relationship soon follows suit.

This questioning of the role of representation expresses, as Gutting (1989:183) puts it: a fundamental “need for a new sort of reflective enquiry that probes the origins and basis of the mind’s powers of representing objects”. The divisions in the field of knowledge that inaugurate the modem episteme are thus due to the decline in the Classical conception of the unproblematical relation of representation to its objects.

Kant’s critique of representation produces two new theoretical domains. Firstly, there is the theory of “transcendental subjectivity”, where the idea is that the mind constitutes its own “objects of representative knowledge” (Foucault, 1973:184). Secondly, and complementarily opposed to this theory of the subject, is what Foucault points to as a transcendental philosophy of the object (or metaphysics), which emerges from the empirical sciences of life, labour and language.

However, a third position, which takes the form of an evasive detour through both of the others, also becomes possible - one in which no transcendental grounding for empirical knowledge is deemed necessary and knowledge is restricted to the field of direct experience. This position is usually described pejoratively as positivistic. It takes shape as the voice of actual experience - an attempt to unite ‘positivism’ (the discourse of the body, the object, and the empirical) with ‘eschatology’ (that of the self, the subject, the transcendental). The discourse of actual experience is thus a ‘discourse of mixed nature’. It plays the role of an apparent mediator (because the concepts are apparently radically contesting) between “the space of the body and the time of culture” (Foucault, 1973:321), but is actually the articulator of the two. In other words, the discourse of actual experience enables the subject to understand itself as both an object of the empirical and to be positioned as the transcendental precondition for this objectivity.

As a result, Foucault points out, especially in the last sections of The Order of Things (1973), epistemological and psychological problems permeate and collapse upon each other in the modem age, precisely because of what he calls the “double status” of man. Foucault’s renowned account rests on the understanding that man’s problematical double status is based on the fact that, for modernity, man is both the foundation of all knowledges and an object of enquiry within (or for) them - both the source of knowledge and an empirical element; a thing among things which must be known in the same way as they are.

The Visual Field

On the face of it, as many commentators have pointed out, Foucault’s opening gambit of an extensive and exhaustive exegesis of Las Meninas in The Order of Things is apparently misleading. It is a superb piece of close reading, but seems to bear an attenuated and opaque connection to what comes after it in the book. In fact, the methodical yet lyrical analysis establishes the possibility of a new set of relationships in the mysterious painting, defined by a number of different vectors of vision.

Without wishing to rehearse all of these different vectors in detail, it has been widely remarked that Las Meninas lacks a central point of perspective, a vanishing point on the model of Da Vinci’s The Last Supper (1494-1499). Of all the visual and compositional tricks in Velasquez’s great work, one is key: the gazes and visual vectors of all the protagonists, the subjects, of the painting are being held by something not in the painting. That something is of course the place of the sovereign, the royal couple, indicated only in a spectral and absent presence by their shadowy reflection in the mirror painted in the mid-ground – a position still not at the perspectival centre of the composition. And yet, and yet….as Foucault points out (1974:15), this place outside the painting is shared between the sovereign and the spectators, the viewers, themselves:

What Foucault’s analysis points to here is the ways in which the painting is indicative of the demise of representation in its ‘Classical’ mode – the painting is a symptom of ‘the withdrawal of knowledge and thought outside the space of representation’. It puts representation into the frame as both a means and an end – a subject and an object, and problematizes the gaze that lies outside the purview of the frame itself, that conditions those gazes and representational vectors within the frame. It is an early example of a work of art which represents representation itself.

As Dixie’s work To be King hypothesises, this nascent ‘doubling’ of the visual field coincides historically with the formalising of the colonial project. Her dense, lyrical, atmospheric and troubling video installation sets out, at one pole, the atomisation and recontextualisation of the minutiae of its masterpiece template, Las Meninas. At the other pole lies a welter of images extending the vectors of the original painting beyond the frame bounded by the original work and its implicated viewers. In this welter a ship emblematic of early colonial slavers and trading ships common to Spain, one of the earliest colonial powers, sails off the edge of the ocean; the artist, standing in for the painted figure of Velásquez, becomes a paper cut-out comprising pages from Foucault’s The Order of Things, and crumbles away on the wind blowing over an Eastern Cape landscape called Burnt Kraal; roles are taken on, reversed, doubled, relocated to the backdrop of a classic colony, the Eastern Cape. Dixie’s animations and multimedia interventions layer palimpsest upon palimpsest, offering thought by way of a radical re-vision. What if, she says? What if the Infanta was black, and stood mutely outside the frame of the picture? What would make this possible, what transmutation of thought and representation? How would it change things, if the Southern Cross was the constellation guiding the centres of political power and the rules of representation?

There is so much else in the depths and instantiations of the work, a set of visual, aural and multimedia tableau which hint at a critique, yet manifest, ultimately, as a profound meditation in both media and concept, on the forms of thought, knowledge, representation and social order first set out by Foucault’s use of Las Meninas as template. And Dixie’s work yet manages a personal lyricism that belies the enthusiastic austerity of the original essay’s magisterial thinking. At its heart, but off-centre, is the face of her daughter, the Infanta manqué, the skeined inscription of a bond at the heart of a bewildering matrix of representation.

That space where the king and his wife hold sway belongs equally well to the artist and to the spectator: and in the depths of the mirror there could also appear – there ought to appear – the anonymous face of the passer-by and that of Velázquez. For the function of that reflection is to draw into the interior of the picture what is intimately foreign to it: the gaze which has organised it and the gaze for which it is displayed. But because they are present within the picture, to the right and to the left, the artist and the visitor cannot be given a place in the mirror, just as the king appears in the depths of the looking-glass precisely because he does not belong to the picture.

References:

Foucault, M 1973. The Order of Things. London : Tavistock. Foucault, M. 1977a Discipline and Punish. Harmondsworth : Penguin Foucault, M 1977b. The Father’s No. In: Foucault, M. Language, Counter-Memory, Practice. Ithaca : Cornell University Press, p. 68-86. Gutting, G. 1989. Michel Foucault’s Archaeology o f Scientific Reason. New York: Cambridge University Press.