2 minute read

Exchanging

PREFACE

Foucault has both a Foreword and a Preface. He begins the Preface by describing himself laughing. At words on a page (the Chinese classification system for animals which I list in the chapter Classifying). This bodily response to words reveals his humanity to me, his corporeality. The image of him laughing and reading, enabled me to visualise him.

Advertisement

It is in his articulation and scrutiny of what it is that made him laugh, ‘though not with a sense of uneasiness that I found hard to shake off’ [1] that he first describes his concept of heterotopia.

In 1967 Foucault develops this concept of heterotopia in his paper Of Other Spaces, Heterotopias which he delivered to an audience of architects. ‘The role of the heterotopia as ‘place of Otherness’ – which, incidentally, is the literal translation of the original Latin term – is central to Foucault’s elaboration of the term.’ [3]

Derek Hook, quoting Genoccchi suggests that: ‘In The Order of Things Foucault’s discussion of heterotopia centres upon a discursive/linguistic site in contrast to... an examination of actual... locations (as in Of Other Places’)...[4]

Five of the ‘actual locations’ discussed by Foucault in his 1967 paper are: the theatre, the ship, the mirror, the colony and the museum. It is these spaces, both mythical and real, with which To Be King engages. Hook points out though that, ‘one should not automatically assume that the analytics of heterotopia refers exclusively to places. We should apply the notion of the heterotopia as an analytics rather than simply, or literally, as place, it is a particular way to look at space, place or text.’ [5]

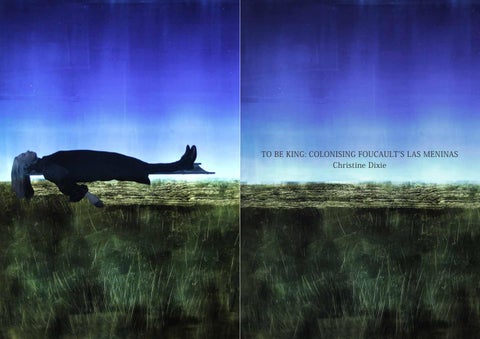

In my text, To Be King: Colonising Foucault’s Las Meninas, I use the word colonising in the sense of ‘appropriate (a place or domain) for one’s own use’. I also use the word to indicate the spatial relationships that are a major concerns in To Be King. The five heterotopic spaces, described below by Foucault in ‘Of Other Places’ [6] are interwoven into a desription of the installation.

Heterotopias are disturbing, probably because they secretly undermine language, because they make it impossible to name this and that, because they shatter or tangle common names, because they destroy ‘syntax’ in advance, and not only the syntax with which we construct sentences but also that less apparent syntax which causes words and things (next to and also opposite one another) to ‘hold together’. [2]