12 minute read

Caledonian Canal

Lochs and locks

Miranda Prynne narrates a cruise through the Caledonian Canal taking in the legendary Loch Ness

Alocal saying in Western Scotland: “If the sun is shining, it’s going to rain.”

Few utterances have more truth.

Pete and I had been sailing up the west coast of Scotland for three weeks by the time we reached Fort William and had probably endured about 60 squalls – averaging about three per day.

Yet testing weather, ferocious tides, big seas and all, I would not hesitate in stating that Western Scotland is the most spectacular place I have ever sailed.

It is mythical in its proportions, mysterious in its emptiness and medieval in its scenery

It is like sailing through a Tolkienesque fantasy.

Our original plan had been to make it all the way to Orkney before sailing back down the east coast but, as is so often the way with sailing, we ran out of time. The incredible coastline with its islands, lochs and coves all beckoning us in, waiting to be explored, combined with the erratic weather conditions and some of the strongest tidal races in the world, meant even the best laid passage plans often went awry.

But our forced shortcut proved a blessing in disguise. By the time we reached Fort William we had endured enough angry seas and minor gales to satisfy all but the most intrepid sailors. While in awe of our surroundings, we had been wet and cold for nearly a month and the prospect of sheltered tide-free waters seemed as welcome as a hot bath.

We motored out of Fort William mid morning on 17th September to hop up Loch Eil to the entrance to the Caledonian Canal at Corpach, where there is a fuel point for those needing to fill before heading up the canal. There was a fair amount of faff and waiting around before we could lock into the canal but by 2pm we were chugging our way towards the lock flight ‘Neptune’s Staircase’ at Banavie, with Ben Nevis and his mountain clan looming over us, for a rare moment free of cloud cover.

There was a cheerful audience to admire us as we carefully negotiated N’Tiana’s 13-tonne bulk up through the seven locks. Unlike narrowboats, yachts are not designed for canal locks and this is very evident when trying to steady and stabilise them against the inflow or exit of water. Thankfully we had a friend who had joined us for the trip through the canal and an extra pair of hands was invaluable when keeping the boat steady as we rose and fell. It meant one person with a lead on the bow, one on the stern and one fending off the wall and other vessels sharing the lock. Pete and I had also had plenty of practice when traversing the Crinan canal a few weeks before.

As we progressed up the Great Glen, the huge and ancient fault line that splits Scotland in two, the weather pressed in upon us. A thick grey mizzle blanketed the highlands hiding the peaks but cocooning us amidst the luscious green tranquillity of the tree lined canal banks which gave way to a backdrop of softer slopes reaching into the clouds.

ABOVE LEFT

Happy to shelter from angry seas on the first part of the Caledonian Canal

BELOW

N’Tiana on Neptune’s Staircase

Torrential rain

We were forced to moor up before reaching Gairlochy as darkness descended. It was in the nick of time for at this point the weather took a sudden turn from grey and uneventful to a violent deluge that showed no signs of letting up until morning. We battened down the hatches and took advantage of our stationary state to cook a hot stew which we followed with a night cap of whisky picked up at the Oban and Tobermory distilleries a week before.

The next morning we were up at dawn, determined to cross Loch Ness before dark fell once again which

The boat: N’Tiana

A beautiful Oyster 435 – a 43-ft (13.2m) ketch – built by Oyster

Marine in 1986. Designed by Holman and Pye of

Colchester, with a fibre-glass hull and encapsulated keel, she weighs in at just over 13 tonnes. With a draft of 6 ft 6 (2m), her waterline length is 36 ft (11.25m) and beam is 14 ft (4.2m). With a 60 ft (18.3m) mast, she has a 821 sq ft (72.27 sq m) sail area She has six berths with three cabins with a large central cockpit. N’Tiana is one of just 65 Oyster 435s that were built between 1983 and 1995 – they proved to be the second most popular

Oyster design ever made.

meant reaching Fort Augustus at the south western end of the loch by lunchtime. The early start paid off, by 7.20am we were through the swing bridge and the lock leaving Gairlochy in our wake we floated out into Loch Lochy. It was eerily still with a thin shawl of mist lying across dark shoulders of the highlands, tickling the treetops perfectly reflected in the glassy water. As the mist thickened, it gave the impression we were floating through a tunnel in the clouds.

The silence of the weather forced us to keep the engine on as we crossed Loch Lochy which despite being less than 10 miles long, is the third deepest loch in Scotland reaching depths of 531-ft. The steep forested slopes fall directly to the water on either side, giving it a fjord-like appearance.

We motored serenely across to reach the lock at Laggan with its sprinkling of homes nestled against the waterside in just over two hours. Here the canal carried us for just a mile and a half to the smallest of the Glen’s key lochs, Loch Oich, whose dimensions make it feel more like a slow flowing river than a lake. Its thickly forested banks crowded in upon us through the mist almost within touching distance as we covered its four mile length.

A swing bridge at the northern end granted us entrance to the next section of canal. We had not seen another boat or human on the move all morning. Our engine cut through the heavy silence like a clumsy intruder, all was still apart from the wavelets left in our wake. The mist had lifted into the bruised moody skies to reveal the heather adorned highland slopes in all their glory. There was little to do but sit and stare and take in the rugged beauty that surrounded us on all sides.

Then around another bend there was Fort Augustus. Suddenly we were surrounded by all the hustle and bustle of a sizeable settlement and tourist honeypot. After a morning of quiet contemplation among the mountains, this sudden explosion of humanity was a cheerful interruption on our peace.

Loch Ness

It was about 1pm when we moored up alongside several other vessels, mostly motor boats under charter, all waiting to descend through the lock ladder and be released out into the famous waters of Loch Ness. We had been warned there can be quite a hold up at Fort Augustus as a limited number of boats can go up or down through the five locks at any one time and with several vessels negotiating their way carefully through each lock together, it takes some time. Even off season we only just made it into the first batch descending. Others who arrived shortly after us were not so lucky and would have had a long wait before another group was allowed down.

I dashed ashore to explore shop and café options and soak up the liveliness and chatter after so much silence and stillness. Sitting at the southern end of Loch Ness, Fort Augustus is the obvious launch pad for many visitors wishing to explore the famous loch and surrounding highlands. It is also a good stopping place for anyone travelling the length of the Great Glen whether on foot, wheels or like us, water. With good lunch spots and shops for reprovisioning, it is a pleasant place to be stuck for a couple of hours if you do find yourself with a long wait for the lock ladder.

Caledonian Canal staff oversee the lock ladder, clearly instructing on where the various boats should place themselves and helping with lines. With so many novice crews on newly chartered motorboats crowding into the locks together, this was a huge help and a great relief to all. The whole process still took nearly two

ABOVE

Fort Augustus on Loch Ness

BELOW

En route to Loch Oich

hours but was a good humoured with few hiccups and everyone dutifully concentrating on their respective roles, be that fendering or keeping the lines fast. At 3.30 the heavy gates of the final lock opened unleashing us into the dark waters of Loch Ness.

Gimme shelter

The wind had picked up from the south west bringing with it warnings of a storm sweeping its way across the Atlantic towards UK shores. We needed to reach the shelter and security of the moorings at the other end of Loch Ness before it struck.

So with the wind almost directly on our stern we loosened the sails and let ourselves be propelled along Loch Ness. Giant cumulonimbus clouds were gathering far behind us in the west but the sky above was clear. The sun lit our course and a rainbow rose out of the waters ahead of us, like a good omen beckoning us forth.

We gybed on into the sunshine, the waters sparkling around us, the greens and purple hues of the hillsides bought alive by the unfiltered light. After a mile or so we goose winged the jib and coursed north east.

We had a glorious sail through that late September afternoon with a fresh south westerly breeze powering us along at over eight knots. Coastal sailing is abundant in amazing scenery but usually only on the landward side, here we were surrounded by Scotlands geological wonders on every side. As we sailed north east towards Inverness, the steep highland slopes of the west steadily gave way to softer slopes of forest and farmland.

Loch Ness is 23 miles long but we flew across it in about three and a half hours, chasing the sun which glided westwards remaining just out of reach of the clouds and warming our faces and moods. At its northern end there is no lock but the loch narrows to resemble a river.

Dropping the sails, we motored up to the mooring spaces just before the lock at Dochgarroch. It was a beautiful spot with an azure evening sky above us and towering clouds lit gold rising in the west – the calm before the storm.

We celebrated our successful evasion of the Loch Ness monster by sampling more of the many whiskies we had acquired while exploring the Western Isles. The wind built

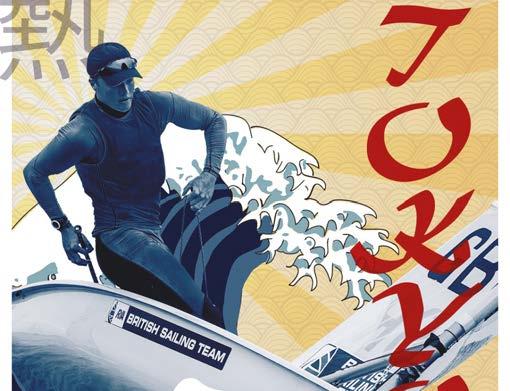

ABOVE RIGHT

Nessie!

BELOW

Urquhart Castle on Loch Ness

overnight bringing with it dark thunder clouds and rain but once through Dochgarroch Loch the next morning we had just a short motor of less than an hour before we were floating through the outskirts of Inverness. A four lock ladder and swing bridge took us down into the basin at Merkinch where we spoke to the Caledonian Canal authorities.

A lock is the key

A smiling lock keeper came down to work the Clachnaharry Sea Lock. There is a strong current in the sea lock due to the tide racing in and out of the Inverness and Beauly Firths so we had to keep a careful control of the lines to stop N’Tiana violently swaying. But under the experienced supervision of the lockkeeper who oversaw the operation with swift efficiency, before we knew it we were motoring into the open flowing waters of the firth.

There is a sandbank north east of the canal entrance so any vessel heading to Inverness Marina must first head out and stay in the white sector of the Longman Point Beacon before turning in and following the clearly marked entrance to the River Ness.

By the time we reached Inverness Marina and squeezed our bulk into one of the few remaining spaces, the wind was howling. We turned off the engine at 11.57am just before Storm Aileen began her onslaught.

In two days we had travelled 60 miles - 38 miles of natural lochs and 22 miles of canal cuttings – traversing 29 locks and 10 bridges to cross from one side of Scotland to the other. The same journey going round by sea via Orkney could have taken weeks, depending on the weather and sea states.

But leaving aside the huge time saving of the Caledonian Canal, it is a feast for the senses and offers a sailor a novel way to enjoy being on the water and fresh roster of practical challenges. After many weeks of coastal sailing, we welcomed the change. A crew with more relaxed time constraints could easily spend several days traversing the canal, heading ashore and exploring the wilds around the canal on foot as well as by water. Others may find a canal too restrictive and resent the need to use the engine so much. It is down to personal preference but few sailing experiences will ever compare for pure beauty and enjoyment as that afternoon chasing the sun across Loch Ness overlooked by the marbled mountainsides of Scotland.

ABOVE LEFT

Approaching Inverness

The Caledonian Canal in numbers

Total length of the canal: 60 miles (96.6 km) or 50 nautical miles Length of natural lochs: 38 miles (61.2km) Length of canal cuttings: 22 miles (35.4 km) Summit level at Loch Oich: 106 feet (32.3m) Number of Locks: 29 Number of Bridges: 10

Practical information on the Caledonian Canal

Minimum time needed to cross the canal: 2.5 days Maximum dimensions for vessels: 150 ft (45.72 m) long; 35 ft (10.67m) beam; 13.5 ft (4.1m) draft. Vessels with draft over 12.5 ft (3.8m) are advised to contact the Canal Office before arrival to ensure there is sufficient water. Maximum mast height in the canal is 115 ft (35m) above the waterline, but clearance under the Kessock Bridge on the Inverness Firth is lower at 89.8 ft (27.4m).

All locks and gates are operated by Scottish Canals staff between the following hours:

Winter: Monday to Friday 9am to 4pm Spring & Autumn: Seven days 8.30am to 5.30pm Summer: Seven days 8am to 6pm

Tidal restrictions of the sea locks:

During normal operating hours, Corpach Sea Lock is available ≥ 1m, and Clachnaharry Sea Lock is available ≥ 1.4m. At low water and spring tides the sea locks are closed for around two hours either side of low tide. For more details and advice go to www.scottishcanals.co. uk/canals/caledonian-canal.