8 minute read

Sutherland’s shame

Words by ROBERT JAMES

The Highland Clearances were a notorious and controversial period in British history. In the first of two articles, we look at how the clearances played out in the northwest Highlands

ABOVE:

Dunrobin Castle, the seat of the earls and dukes of Sutherland T he roots of the Highland Clearances can be traced back to 1609 when King James VI decreed that sons of clan chiefs should be educated in lowland Scotland and taught the English language.

In time, this policy led to the gentrification of the clan chiefs, acclimatising them to aristocratic living, a lifestyle they loved but could ill afford. To pay for this new lifestyle, their ancestral lands were mortgaged, and, in many cases, the ownership of those lands transferred to creditors.

In truth, the land was never the chieftains’ to sell; the chief was a guardian of the clan’s territory, giving tacks of land to his people in return for their loyalty, tribute and military support. This centuries-old system of patronage had served the clans well but in the new world after the Battle of Culloden in 1746, Highland chiefs no longer had a need to raise armies, what they really needed was cash. So it was that ancestral lands were sold and along with it, the clan’s people who occupied them. The new owners seldom had familial links to the clan and thus the chiefs had now been replaced by landlords.

And so, to the county of Sutherland – the clan lands of Gunn, Mackay, MacLeod and Sutherland. By the late 18th century, every one of these clan chiefs was in debt, some of them seriously (Mackay of Strathnaver owed £58,000 or £57 million in current valuations).

The chief of Clan Sutherland was Elizabeth, The Countess of Sutherland. She inherited the title and estate, the largest private estate in Europe, as an orphaned one-year-old child. By the time of her marriage in 1785 to Earl George Leveson-Gower, the one-million-acre estate was in debt, with large tacks of land mortgaged. Had the Countess not married the Earl, her estate could well have gone the same way as so many others – sold off to creditors. However, in 1803 her husband inherited the title of Marquess of Stafford along with a vast fortune, making him the wealthiest man in Europe. At this time, Scotland was undergoing a revolution in farming practices. Lower lying rural land was being drained, enclosed and improved whilst hitherto unproductive uplands were populated with new breeds of sheep that were able to withstand the harsh upland moors. Several Highland landlords began to embrace these new agrarian opportunities and soon showed that income per acre could increase by up to a factor of six over the incumbent subsistence farming methods. Seeing the opportunity to leverage their great wealth, the Marquess and Countess embarked upon a 50-year investment plan to improve their Sutherland estate. The process was largely delegated to the Countess to oversee, it was after all, her ancestral land. The Countess began by purchasing the land held by neighbouring indebted clan chiefs of the county of Sutherland and, by 1805, she owned most of the county. The Countess may have become the overlord of most of the county, but she had no direct relationship with its inhabitants – she too had morphed from clan chief into commercial landowner. Land improvements were initiated, and The Countess may have been overlord of expert agriculturalists were recruited to oversee the work. One such expert was most of Sutherland, but she had no direct Patrick Sellar from Moray who arrived at relationship with its inhabitants Dunrobin Castle, (the seat of Clan Sutherland) in 1809 with ambitious

CLOCKWISE, FROM TOP LEFT:

Elizabeth LevesonGower, Countess of Sutherland; ‘The Emigrants’ statue in Helmsdale commemorates those who lost their homes in the Highland Clearances; King James VI of Scotland

plans to turn the largely subsistence economy of the Sutherland estate into a supply house for industrial Britain. The process was, in the mind of the Countess, simple. Give notice to tenants at the end of their lease, relocate them to unproductive lands upon the coasts and provide them with small their lease, relocate them to unproductive lands upon the coasts and provide them with small croft lands to rent for their subsistence while simultaneously encouraging their participation croft lands to rent for their subsistence while simultaneously encouraging their participation in the cash economy – predominantly the sea fi shing trade. To facilitate this, the estate would in the cash economy – predominantly the sea fi shing trade. To facilitate this, the estate would invest hundreds of thousands of pounds in building infrastructure to support the transition. invest hundreds of thousands of pounds in building infrastructure to support the transition. Meanwhile, the vacated lands would be converted into large farms and leased to the highest bidder – lowland coastal plots would become arable and pastoral farms, while the inland bidder – lowland coastal plots would become arable and pastoral farms, while the inland straths and hills would be ideal for the rearing of vast fl ocks of sheep. The process of eviction and relocation began in 1809 and from the perspective of the Countess, all proceeded well. However, in 1813 the two thousand tenants of the southern straths of the parish of Kildonan rioted when they were confronted with eviction, necessitating the deployment of a regiment of foot soldiers from Fort George in Inverness to keep the peace. Undeterred, the Kildonan residents embarked upon a well organised campaign to publicise their predicament, which ultimately made the London newspapers. This campaign not only bought them time, it also aroused the support of an opponent to land clearances, who offered one hundred places for assisted emigration to Canada; one thousand residents applied. Eventually the Earl and Countess won though, and the remaining residents of Kildonan reluctantly moved to coastal lands on the Sutherland estate or migrated away from the county entirely to fi nd work elsewhere.

Patrick Sellar was embarrassed by the episode, as it was his responsibility to oversee the orderly relocation of tenants. He had never understood the Gaelic culture nor respected the ancient ways of the clans, labelling the Gaels as “aborigines” and “beggars with no stock but cunning and laziness”.

The following year, Sellar proceeded to clear the northern reaches of Kildonan and lands of Strathnaver. This time, he was to be the benefi ciary of the evictions as he had signed a lease to farm these lands for sheep.

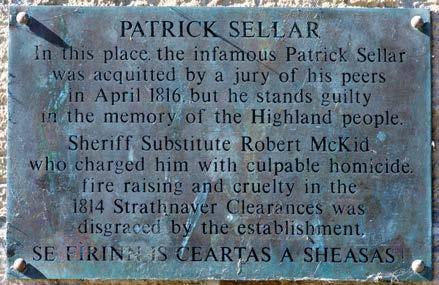

ABOVE:

Helmsdale village INSET: A plaque in Inverness marks where Patrick Sellar was imprisoned and put on trial

DON’T MISS

CLOCKWISE, FROM LEFT:

A dilapidated cottage in Alltnacaillich leftover from the Highland Clearances; a bird’s-eye-view of Learable, where you can see the traditional fi eld drainage system and outlines of buildings (right); River Helmsdale the second part

Not wishing to endure the frustrations and embarrassments of 1813, Sellar changed of our story tactics. No longer content with allowing people to leave their homes in their own good tactics. No longer content with allowing people to leave their homes in their own good next issue time, he violently ejected them and immediately set light to the buildings to ensure the time, he violently ejected them and immediately set light to the buildings to ensure the residents could not return. If people resisted, Sellar ordered the houses to be set alight with residents could not return. If people resisted, Sellar ordered the houses to be set alight with their inhabitants still inside. On one occasion, confronted by a house still occupied by an infi rm woman in her nineties, he shouted in anger and frustration, “Damn her, the old witch, she has lived too long; let her burn,” whereupon the house was set alight. Though rescued, the old lady died days later.

Undeterred, Sellar continued to clear the land in this brutal fashion, turning ancient townships into burning ruins and reducing once proud clans folk to terrifi ed hollow wrecks.

The Countess knew of his methodologies, commenting in 1814 that “Sellar is exceedingly greedy and harsh with the people [and] the more I see of him, the more I am convinced he is not to be trusted further than he is at present.” She did not, however, terminate his employment.

Sellar was ultimately arrested for his actions in Strathnaver. In 1816, he was tried and acquitted of culpable homicide in a trial lasting less than a day, whereafter he immediately recommenced his employment with the Countess. He was to go on to oversee yet more forced evictions on the Sutherland estate until he was fi nally dismissed in 1817. He remained a tenant of the estate until his death in 1851, inhabiting and farming the very lands he had so brutally cleared.

Between 1809 and 1820, 15,000 people were forcibly evicted from their ancestral lands on the Sutherland estate. S

No longer content with allowing people to leave in their own good time, Sellar violently ejected them and set light to their homes

Robert James runs North Coast Explorer with his wife Sally-Ann, o ering private, bespoke tours of the northwest Highlands, including to some poignant places linked to the clearances. northcoast.scot