literature

| Ossian poems

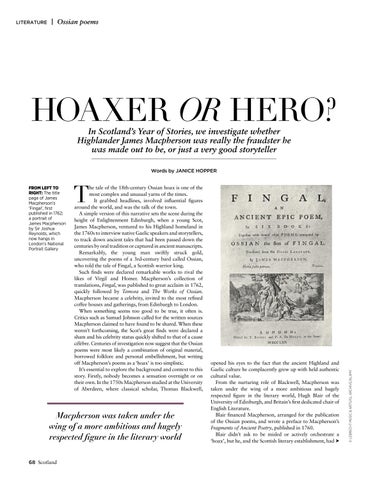

HOAXER OR HERO? In Scotland’s Year of Stories, we investigate whether Highlander James Macpherson was really the fraudster he was made out to be, or just a very good storyteller Words by JANICE HOPPER

T

he tale of the 18th-century Ossian hoax is one of the most complex and unusual yarns of the times. It grabbed headlines, involved influential figures around the world, and was the talk of the town. A simple version of this narrative sets the scene during the height of Enlightenment Edinburgh, when a young Scot, James Macpherson, ventured to his Highland homeland in the 1760s to interview native Gaelic speakers and storytellers, to track down ancient tales that had been passed down the centuries by oral tradition or captured in ancient manuscripts. Remarkably, the young man swiftly struck gold, uncovering the poems of a 3rd-century bard called Ossian, who told the tale of Fingal, a Scottish warrior king. Such finds were declared remarkable works to rival the likes of Virgil and Homer. Macpherson’s collection of translations, Fingal, was published to great acclaim in 1762, quickly followed by Temora and The Works of Ossian. Macpherson became a celebrity, invited to the most refined coffee houses and gatherings, from Edinburgh to London. When something seems too good to be true, it often is. Critics such as Samuel Johnson called for the written sources Macpherson claimed to have found to be shared. When these weren’t forthcoming, the Scot’s great finds were declared a sham and his celebrity status quickly shifted to that of a cause célèbre. Centuries of investigation now suggest that the Ossian poems were most likely a combination of original material, borrowed folklore and personal embellishment, but writing off Macpherson’s poems as a ‘hoax’ is too simplistic. It’s essential to explore the background and context to this story. Firstly, nobody becomes a sensation overnight or on their own. In the 1750s Macpherson studied at the University of Aberdeen, where classical scholar, Thomas Blackwell,

Macpherson was taken under the wing of a more ambitious and hugely respected figure in the literary world 68 Scotland

opened his eyes to the fact that the ancient Highland and Gaelic culture he complacently grew up with held authentic cultural value. From the nurturing role of Blackwell, Macpherson was taken under the wing of a more ambitious and hugely respected figure in the literary world, Hugh Blair of the University of Edinburgh, and Britain’s first dedicated chair of English Literature. Blair financed Macpherson, arranged for the publication of the Ossian poems, and wrote a preface to Macpherson’s Fragments of Ancient Poetry, published in 1760. Blair didn’t ask to be misled or actively orchestrate a ‘hoax’, but he, and the Scottish literary establishment, had

© LEBRECHT MUSIC & ARTS/GL ARCHIVE/ALAMY

FROM LEFT TO RIGHT: The title page of James Macpherson’s ‘Fingal’, first published in 1762; a portrait of James Macpherson by Sir Joshua Reynolds, which now hangs in London’s National Portrait Gallery