15 minute read

SAUBER MERCEDES C11

Class of 1990

Mercedes’ C11 is as robust today as it was when it took the 1990 World Sportscar Championship title

By Lawrence Butcher

The Mercedes C11 was a pivotal car in Mercedes’ modern motorsport history as in some respects it paved the way for the manufacturer to return to Formula 1. Through its young driver programme, it was also the car that provided Michael Schumacher with his only Le Mans start, sharing in 1991 with Karl Wendlinger and Fritz Kreuzpointner.

Swiss outfit Sauber first became involved with Mercedes in the early 1980s. Mercedes engineers provided some informal development work to help with Sauber’s C6 and C7 Group C cars. Unhappy with the performance of BMW’s straight-six engine it was using at the time, Peter Sauber had approached Mercedes for an engine supply, which initially came in the form of the 2-valve M117 V8, and then following came the four-valve, 5-litre, M119 V8.

Officially, these engines were prepared by fellow Swiss Heine Mader but in fact the bulk of work was undertaken by Mercedes at its engine facility in Untertürkheim, under the supervision of Hermann Hiereth. The Mercedes engined C8 arrived in 1985, and the company’s branding came the next year.

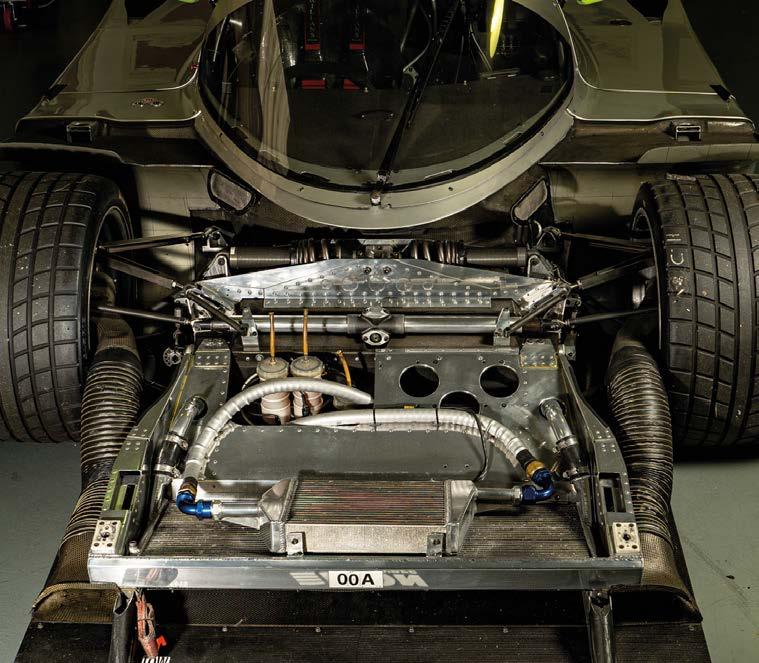

The C7, 8 and 9 were all evolutions on a theme. The monocoque dated back to 1982, designed by Leo Ress while he was between jobs at Mercedes and BMW. Ress eventually joined Sauber full time in 1985. While not an entirely clean sheet design, the C11 was the first of Sauber’s cars to be built with full Mercedes backing and it benefited from the company’s resources that entailed,

Mercedes’ C11 contested the FIA World Sportscar Championship in 1991 before it delivered the company its most recent win at Le Mans. The test mule has received an extensive make over at specialists BBM to allow it to run in modern classic events

hence the car featured a Mercedes Benz rather than Sauber designation.

The first car was chassis C11-89-00, which embodies a fascinating point in the mid-evolution between the alloy chassis C9 and the carbon-tubbed C11. The car has been owned and run by Northamptonshire based BBM Sport for the past 12 years and as such, Technical Director Steve Briggs knows it inside out.

Although the first of its kind, chassis 00, which is pictured in this feature, is still actively campaigned in Historic Group C racing, having taken a number of high-profile wins and regularly running at the front of the pack. In fact, during one outing at Spa in 2011, its qualifying time of 2m05s would have put it in sixth place on the LMS grid running that same weekend.

Briggs notes that there are a number carry over parts on chassis 00 from the C9. For example, the routing for the turbocharger air feeds is different between this car and those that went on to race in period. Similarly, it has an aluminium front crash structure, while the later cars were all carbon. The most obvious difference at the front of the chassis is the suspension mounting structure. This is a fabricated aluminium construction, bolted to the carbon tub, while on the race versions it was carbon fibre and fully integrated with the rest of the chassis.

Home run The car was delivered to BBM directly from Sauber complete, but still in need of an extensive recommissioning before it could be raced. This entailed an engine and transmission rebuild, along with replacement of the coolers and other heat exchangers. At the same time, all of the suspension components were crack tested.

The car was ran successfully before a crash at Donington in 2012 led to the replacement of some suspension components. However, a fire at Monza in 2015 necessitated more extensive works. A fuel rail in the engine bay had split and set the rear alight. ‘It was an aluminium fuel rail that cracked,’ explains Briggs. ‘The engine had a vibration. I think it had been over revved, and that caused a timing guide to fail.’

A failed valve spring bucket bush caused the car run on seven cylinders at the Le Mans Classic in 2018, although fortunately that did not result in a fire. However Briggs remarks that so strong is the car as a package that the problem was not noticed immediately. ‘We think it went at the end of the first round at Barcelona,’ he says. ‘We did a test before Le Mans and the bush failed, sticking the valve open slightly. However, we didn’t spot this, took it to Brands Hatch for a shakedown before Le Mans, and it was fast there. The car went to Le Mans, where it qualified third, but then another driver got in and said it didn’t feel right. We did a leak down test and found it was down to seven cylinders. It wasn’t a dramatic problem, but it was only running on seven. Now we leak down test after every event.’

Mercedes did consider a variety of options for engines when it began the Group C project, ranging from highly boosted I4s through to larger capacity

One of the anomolies for the car was the aluminium crash structure, replaced in race trim with carbon

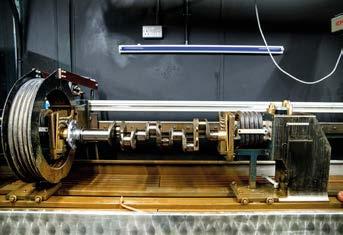

Chassis 89-00 needed a rebuild before it was ready to run, including the engine and transmission

The test car was not even fitted with lights, so BBM took the opportunity to replace the looms as well

V12s in an attempt to strike the best balance for the fuel consumption rules then in play, set at 51 litres/100 km. In the end, it settled on a capacity of 5-litres, with maximum boost pegged at 2Bar (absolute) with a 7500rpm limit and a target weight of 210kg.

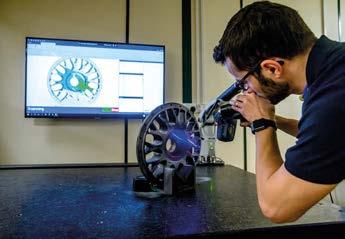

Although it has some spare parts in stock, BBM does have to get some components made for the engines, the maintenance of which is undertaken by Xtec engineering which specialises in Group C cars. ‘It probably gets rebuilt every two to three years,’ says Briggs. ‘We do have a check over every winter and anything that needs doing is dealt with.’

While it is possible to get parts produced, some can prove to be more problematic. For example, the car is currently running the last factory block. If issues arise in the future, a production

car unit will need to be modified. ‘It’s based roughly around the production M119, so if you had a road block, you can weld it up, strengthen it and machine it to work if you really had to,’ says Briggs.

The original blocks are bespoke, with closed deck architecture although the crankshaft was a modified production unit. The race engines also used a simplex chain drive for the double overhead cams, rather than the duplex drive found on the road cars. Oiling is taken care of by a fivestage dry sump pump, with two stages dedicated to turbocharger lubrication. The cooling system is of a parallel design, which theoretically provides almost identical temperatures across all cylinders.

One common problem on cars of this era is handling the original electronics systems. Electronic fuel injection systems were just starting to mature and in the case of the C11, all of the fuelling and ignition was taken care of by a Bosch Motronic MP 1.8 ECU. These are no longer supported by the German firm and finding computers on which to run the software can prove challenging. This leads most who run cars such as the Sauber to update to a modern ECU setup, in this instance a Motec supplied system. The old Bosch ECU is a sizable beast and this has allowed for the new unit to be packaged within the original case, retaining an original appearance.

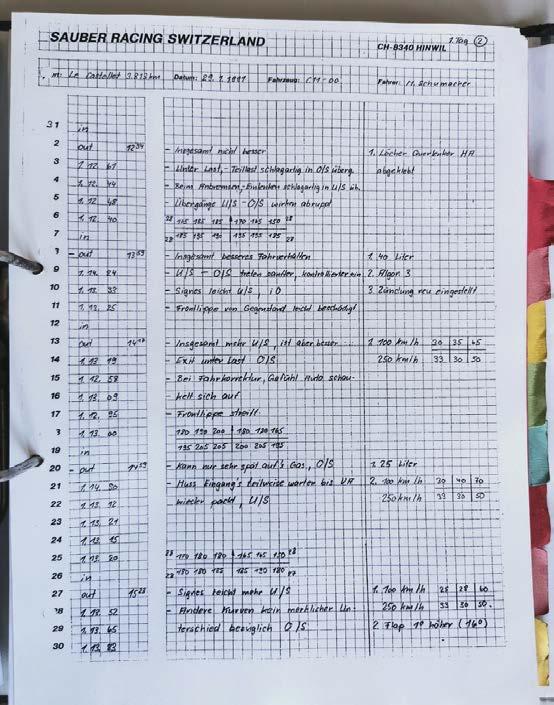

Data logging was present in period, and relied upon another standalone (and large) data logger sited within the cockpit, which prints out a ticker tape record at the end of each run, much like a till receipt. The Motec ECU now handles data duties, but Briggs says that some do still use the original systems. ‘It’s a white box with a few keys and it prints off a load of one and zeros to tell you what is happening. A few are still using them, but they are difficult to get and if they fail, there is only so much you can do.’

On the subject of wiring, when BBM acquired chassis 00, it needed a full rewire in order to be run, not least because being the test car, it was not fitted with equipment such as lights. ‘As the lights were never fitted, it required looms as well and as we were doing all of that, we replaced the whole vehicle loom,’ explains Briggs.

Another modification to ease running has been the replacement of the original wastegates and control systems with modern components. In period an air bleed system, controlled by the ECU and utilising Bosch fuel injectors as solenoids, regulated the opening pressure of the wastegates. This functionality is now handled by the Motec system and incorporated within the ECU housing. There was nothing inherently wrong with the original system, but this approach is easier to manage.

Boxing clever The C11 transmission was an upgrade on the C9, with a Mercedes designed casing that houses mainly Hewland internals. However, it has some features that can complicate maintenance. The C9 ran a Hewland VGC box, which says Briggs, ‘was really the Achilles heel on the car.’ VGC internals are still available and there are companies that manufacture replacement parts.

The only real challenge is the crown and pinion gears, explains Briggs. ‘They use a palloid cut on the gears. The regular VGC has a pair of taper roller bearings, which are preloaded, and has Gleeson type gears with tapered teeth. The palloid cut gears are parallel cut, which allows for a degree of float and they run on angular contact bearings. But palloid cutting machines are very expensive, so most people use Gleesons. The palloid is better and can accommodate more wear.’

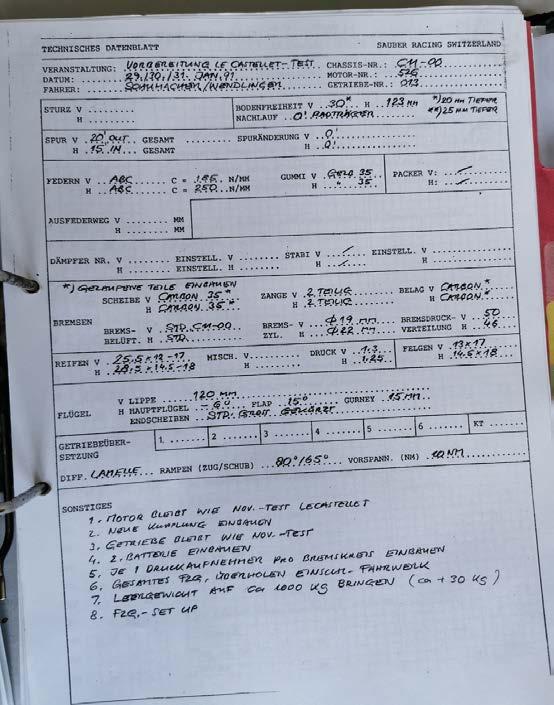

Michael Schumacher conducted testing ahead of the Le Mans 24 hours in 1991 as part of Mercedes’ driver training programme

Steve Briggs

Bespoke AluminiumBespoke Aluminium Radiators,Fuel&OilRadiators, Fuel & Oil Tanksforallmarques Bespoke AluminiumBespoke AluminiumTanks for all marques General Motorsport Fabrication Radiators,Fuel&Oil Tanksforallmarques Radiators,Fuel&Oil Tanksforallmarques General Motorsport Fabrication Suspension & Drive train components manufactured General Motorsport Fabrication General Motorsport FabricationSuspension & Drive train components Prototype & Low Volume Design&Manufacturing In-House CAD, CNC Machining&Rapid Suspension & Drive train components manufactured Prototype & Low Volume Suspension & Drive train components manufactured Prototype & Low Volume manufactured Prototype & Low Volume Design & Manufacturing PrototypingServiceDesign&ManufacturingDesign&Manufacturing In-House CAD, CNC In-House CAD, CNCIn-House CAD, CNC Machining & Rapid Machining&RapidMachining&RapidPrototyping ServicePrototypingServicePrototypingService

www.sifab.co.uk

Email: simon@sifab.co.uk Tel: 01788 568475 www.sifab.co.ukwww.sifab.co.uk Email: simon@sifab.co.ukEmail: simon@sifab.co.uk Tel: 01788 568475Tel: 01788 568475

Morgan Sports Car Specialist

Morgan Sports CarMorgan Sports Car SpecialistSpecialist

PUTTING SAFETY FIRST

• Engine Development • Hub Dyno Facility • Precision Engineering • Aviation Engines • Reverse Engineering

Magnetic Particle NDT • Fluorescent Dye Penetrant Inspection • Ultrasonic Capability (MSB96-10) Engine Components • Roadwheels • Transmission • Suspension • Steering • Drivetrain

12 Ivanhoe Road, Hogwood Industrial Estate Wokingham, Berkshire RG40 4QQ www.nicholsonmclaren.com Contact Roz Shaw roz.shaw@n-mclaren.co.uk +44 (0) 118 973 8022

Unknowingly, BBM had a set of Gleeson type gears made, which without close inspection, look very similar. ‘We had special bearings made as well, because they are not available anymore, and they allowed a degree of float in the pinion,’ explains Briggs. ‘That end float, combined with the taper on the gears, meant the pinion acted like an axe. We went through about six sets in a year but still won the championship. We’d do a race, then qualifying and practice for the next race, then fit a new ring and pinion. We knew what the problem was but had to wait for new gears to be made in Germany.’

Briggs did source a cache of detailed transmission information from Beagle Engineering (originally called Staffs Silent Gears and whose subdivision Elite Racing transmission still produces motorsport gearboxes) that worked on the cars in period. Unfortunately, on the way to collect the information, which was in the form of faxes, it transpired that the company had filled two skips with gearbox internals a year earlier because they didn’t know of anyone running a C11.

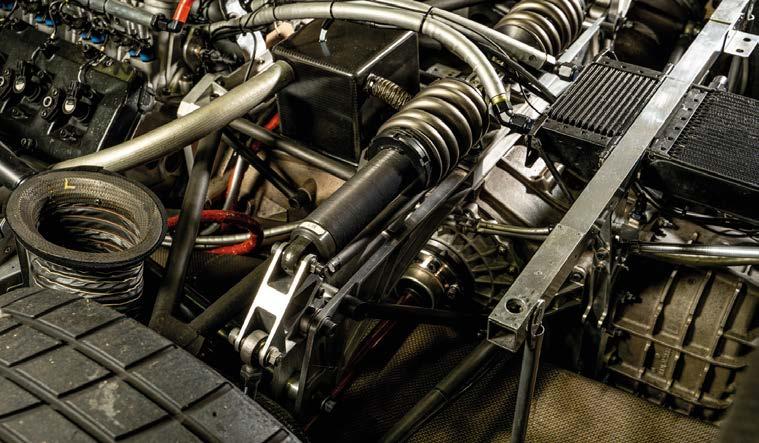

Set up standard As noted, the C11 was considered a benign car in period, and as such, BBM tends to run the car as setup by Mercedes, based on existing notes they obtained. One of the main changes between the C9 to C11 was a switch to pushrod suspension at the rear, from a rocker system, with titanium coil springs and Sachs supplied dampers.

‘The dampers are original, we just get them serviced every year,’ says Briggs. ‘They only have six adjustments. We have all of the testing information from the period, all of the setups, so we just used their base setups. Maybe we could do some work there, but it works well as it is, so why try and reinvent the wheel? Mercedes put 40 million Deutschmarks budget, so they are pretty well sorted. Why would we go away from what was worked out for some of the best drivers, by the best engineers in the world at the time?’

Compared to some of its contemporaries, the C11’s gutsy V8 also helps make it a very tractable machine to drive. Briggs observes that though there are no driver aids such as traction control or ABS, the low-down torque helps make it controllable. ‘There’s no put your foot down, wait, then bosh in you back,’ he says. ‘It’s similar to the AMR1 Aston in that respect. You can put it in gear, let your

The C11 moved to a pushrod rear suspension, and while handling is benign it is effective even today

foot off the clutch and just pull away. You don’t have to rev it. With the C11, the turbos just help it along a bit. They don’t run much boost, around 0.5 bar.’ In this trim, the engine produces around 700-750 bhp. In full qualifying trim in period, the engine was capable of over 1000 bhp, but BBM is clear that at 0.8-0.9 bar boost the engine would not last.

The cars are relatively straightforward to run, says Briggs. ‘You have to remember with Le Mans machines, they were designed to be driven for 45 minutes, stopped, turned back on and driven off. It’s not like F1 where you need 15 people with laptops to start them and if they stop, you can’t restart them.’

History repeating It is inevitable that in competition damage will occur and as such, BBM has had moulds made for the key bodywork parts, taken directly from the existing body. ‘There are some differences between this car and the race ones,’ highlights Briggs. ‘For example, the front bodywork clips on from the top, while the race versions just used pins.’ For the engine cover, which was destroyed in the fire at Monza, a mould was taken from another C11.

The bodywork of Chassis 00 has other features that make it unique from later cars. For example, the trailing edge of the rear wheel arches are add-on items, riveted and bonded to the bodywork. They differ from the C9 in hugging the contour of the wheel more closely and, once the profile was proven during testing, were incorporated as an integral part of the main body. For the last of the Mercedes Group C line, the C291, the curve of this section became even more

Steve Briggs

pronounced. Originally, that section was just clear fibreglass, with a step to the bodywork where it was attached, but it has now been smoothed out.

Although it might make sense to make moulds for all of the bodywork in anticipation of accident damage, this is not always the route customers take with their cars. ‘You can guide the customer and advise them it is a good idea, but you can’t just go out an spend their money saying we’ll get a full set of moulds, because it’s not cheap,’ says Briggs. ‘They might regret it later, but generally, there is always a way around, some way to fix things.’

Despite representing the pinnacle of manufacturer-backed sportscar development in the 1980’s, the C11 is a straightforward car to operate and maintain. BBM looks after a stable of Peugeot’s 908 LM P1 cars, and although these are manageable, they cannot be rolled out, fired up and raced in the way old Group C machinery can.