5 minute read

PICASSO AND PAPER Shining a light on Picasso’s work

PICASSO and PAPER

Curator Ann Dumas joins us to discuss the new exhibition showcasing Pablo Picasso’s work involving paper, on at the Royal Academy of Arts in London

Above, from top: The Royal Academy of Arts in London © Fraser Marr; exhibition curator Ann Dumas © Benedict Johnson

Can you describe what visitors to the Picasso and Paper exhibition will be able to see? Visitors will be able to see works on paper of all types – drawings, prints, papiers collés, collages and even little sculptures – that Picasso made throughout the whole of his long career. e exhibition is displayed in chronological sections, beginning with his earliest works and ending with some of the great prints that preoccupied his nal years. So the visitor can appreciate the whole of Picasso’s very varied development through about 350 works, all selected from a speci c angle – paper, an approach that, as far as I am aware, has never

been undertaken on such a large scale before.

What kind of paper did Picasso use and how did he elevate it to become art? Picasso was fascinated by paper and used all kinds, ranging from expensive historic papers from the French Revolutionary period to the most humble bits of wrapping paper, backs of envelopes and even blotting paper. In his hands, all kinds of paper could become the support for a great work of art. Although he often chose his papers carefully, he was not rigid. A scrap of paper could be used for a highly accomplished drawing.

Picasso loved to incorporate a childlike approach to his work. Do you think his use of paper is tied into this desire somehow? Yes, I do. e earliest works we have in the show are a dove and a dog that he cut from cheap brown paper when he was only nine years old. And many years later, in the 1940s, we nd him doing child-like drawings in coloured pens on little sheets of paper. e informality of paper permitted the possibility of experiment and playfulness.

From the cut-outs to the collages, sculptures to prints, the range of different ways that Picasso experimented with paper is extraordinary. What do you think it says about him as an artist? It is probably not an exaggeration to say that Picasso was the most experimental artist of all time. He was always pushing beyond the boundaries of convention in every medium, experimenting with many di erent printing techniques, for example, and combining techniques such as print-making with photography in new ways. e freedom that paper allowed

Alongside his artwork, Picasso was fascinated with printmaking techniques and sourced rare, antique paper from countries like Japan. To what extent was he inspired by other cultures’ use of paper? Picasso was certainly interested in the art of other cultures, notably African art which had such an impact on his seminal work, Les Demoiselles d’Avignon of 1907, but I don’t think he particularly sought out papers from other cultures. So-called Japan paper, although it originated in Japan, is a term used to describe a particular type of high-quality but widelyavailable paper renowned for its smoothness. Picasso, and other artists, favoured it for drawings, but he would have bought it in France and not imported it from Japan. Picasso particularly loved Japan paper, once commenting: ‘By chance, I managed to get hold of a stock of Japanese paper. It cost me an arm and a leg! But without it, I’d never have done these drawings. e paper seduced me.’

As well as the works of art on show, you also have sketchbooks, letters, cards, illustrated poems and photographs on display. Did he ever discuss about his use of paper or various techniques? ere are few recorded statements of Picasso describing his techniques. However, some of the master printers he worked with commented on his versality and virtuosic skill, and the speed with which he could pick up new techniques in which he had little formal training.

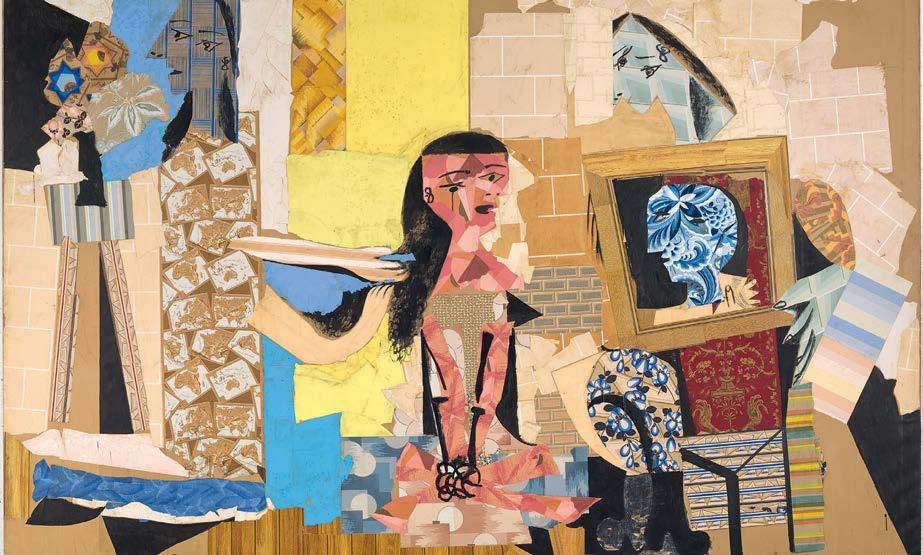

The collage Women at their Toilette (1937-38) is monumental in size, measuring 4.5 metres in length. Do you think his collages inspired other artists to use paper? Yes. Artists who were his contemporaries, such as Juan Gris and Georges Braque, with whom he invented Cubism, as well as many artists in the 20th century, especially the Dadaists such as Max Ernst, Joan Miró and especially Kurt Schwitters, were all inspired by his use of paper. e 20thcentury British artist Peter Blake experimented with cut papers, as did Robert Rauschenberg, and, of course, Matisse with his famous paper cut-outs made at the end of his career.

Do you have a favourite piece in the exhibition? e coloured Minotauromachy etching of 1935. It is, of course, a well-known masterpiece and perhaps Picasso’s greatest print. I nd this enigmatic and poetic work endlessly fascinating. e iconography is complex and draws in many threads that were important to Picasso: the minotaur theme (a sort of alter-ego for the artist), the bull ght, the innocent

girl whose lighted candle suggests hope, and who may allude to his companion Marie- érese Walter. Technically, it is a tour de force of colour etching.

Paper is such a delicate thing, yet some of the works of art seem so strong and sculptural. Was it this juxtaposition that drew Picasso to paper? I think it was fundamentally drawing that kept bringing him back to paper, that and his love of the material itself in all its varieties and his need for experiment.

Exhibition organised by the Royal Academy of Arts, London and the Cleveland Museum of Art in partnership with the Musée national Picasso-Paris.

Above: Pablo Picasso, Head of a Woman, Mougins, 4 December 1962. Pencil on cut and folded wove paper, 42 x 26.5 cm. Musée national Picasso-Paris. Pablo Picasso Gift in Lieu, 1979. MP1850. Photo © RMN-Grand Palais (Musée national Picasso-Paris) / Béatrice Hatala. © Succession Picasso/DACS 2019.

Right: Pablo Picasso, Femmes à leur toilette, Paris, winter 1937–38. Collage of cutout wallpapers with gouache on paper pasted onto canvas, 299 x 448 cm. Musée national Picasso-Paris. Pablo Picasso Gift in Lieu, 1979. MP176. Photo © RMN-Grand Palais (Musée national Picasso-Paris) / Adrien Didierjean. © Succession Picasso/DACS 2019.