6 minute read

THE LAST INVASION

While 1066 is the date scored into Anglophiles’ minds as the last major invasion of Britain, a lesser-known offensive centuries later has all but escaped the history books

WORDS & IMAGES SIMON WHALEY

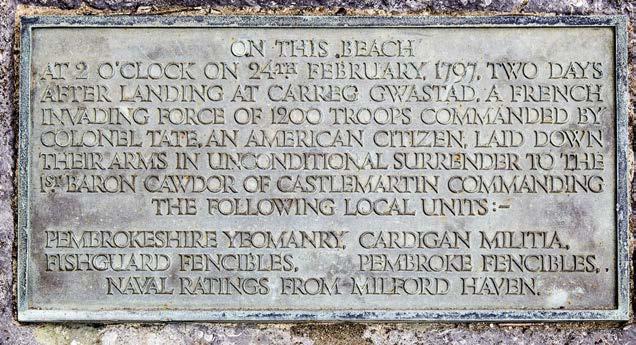

Previous page: The memorial plaque and coast path Top to bottom: The last invasion began at Carragwastad Point; Llanwnda Church In the early hours of 23 February 1797, 1,400 French troops invaded Britain. They were the first hostile foreign troops to set foot on British soil since the Norman invasion of 1066.

They scaled the 160-foot rugged Pembrokeshire cliffs at Carregwastad Point, three miles west of Fishguard, in West Wales. This beautiful but isolated headland juts into the Irish Sea and is so windswept the trees have a permanent stoop.

Led by Colonel William Tate, an Irish-American who fought against the British during the American War of Independence, their mission was to create an uprising among Britain’s rural peasantry. They hoped this would overthrow the British Government, and further the cause of the French Revolution, which was raging across the Channel.

However, these were not France’s finest men. Napoleon had the best soldiers fighting elsewhere, so Tate’s force, who called themselves La Légion Noir (the Black Legion), comprised 600 French soldiers and 800 newly released prisoners, some of whom still wore wrist and ankle shackles. The original plan was to sail into the Bristol Channel, land and capture Bristol – then Britain’s second-largest city – before moving northwards toward Chester and Liverpool.

But an ill wind blew the invading force’s four ships off-course, forcing them around St David’s Head into the relative shelter of Cardigan Bay.

Under the cover of darkness, 16 boats shuttled back and forth, ferrying ashore their ammunition, finally completing the task by 4am. Next, they had to transport it up the precipitous cliffs; eight men lost their lives in the process.

Immediately, the French troops headed inland, and in less than a mile, seized the first property they found, Tre-Howel, which Tate made his command centre.

While they were well stocked with ammunition, they’d brought little else in the way of provisions, and many of the troops hadn’t had a decent meal since leaving France. At daybreak, Tate ordered small groups of his men to reconnoitre the area, find some provisions and secure some horses.

In reality, his troops ransacked and looted isolated farmsteads and smallholdings, capturing chickens, pigs and sheep, frightening petrified locals who fled and raised the alarm.

The troops also discovered large quantities of wine in many of the remote farms, which locals had salvaged from a Portuguese shipwreck a few months previously.

At the medieval Llanwnda Church, French soldiers smashed pews to create firewood and ripped pages from a Bible and the parish records to light them.

As news of the pillaging invaders spread through the community, Thomas Knox, Commander of the local milita, the Fishguard Fencibles, requested urgent reinforcements from nearby Newport, Haverfordwest and Pembroke. Ironically, the local Pembrokeshire

Above: Mosaic detailing the Last Invasion of Britain at Goodwick Below right: Fishguard Fort, which overlooks the harbour

Above left: A memorial to Jemima Nicholas at St Mary's Church, Fishguard Below: Fishguard Fort in the Bay of Fishguard militia were on duty on the east coast of England, the Government having assumed that any European attack would come from that direction.

In Fishguard, 150 volunteers answered the call, and immediately Knox sent 30 to Fishguard Fort to defend the town from any sea attack. He urged Haverfordwest volunteers to hurry: if they had sufficient manpower, Knox planned to attack the French soldiers the following day.

While Knox was struggling to find men, Tate was struggling to control his. Having overindulged on the locals’ salvaged Portuguese wine, many were drunk and more of a danger to themselves. One French soldier took a pot shot at a grandfather clock, convinced the ticking sound was a British soldier preparing his musket.

The following day, 47-year-old Jemima Nicholas of Fishguard heard about the invasion and, armed with only a pitchfork, set off to help her fellow neighbours. When she stumbled across twelve inebriated French soldiers, she single-handedly rounded them up and marched them into Fishguard, where they were held in St Mary’s Church.

Having only secured 600 volunteers, Knox put on hold his plan to attack. Their reconnaissance efforts correctly suggested they were still heavily outnumbered.

Tate’s troops, though, were increasingly worried, claiming to have seen numerous British soldiers in their red and black uniforms scurrying around the Welsh countryside. Realising his troops were no match for the thousands of British militia they believed were in the

area, Tate sent two of his English-speaking men, Baron de Rochemure and François L’Hanhard, to meet Knox in Fishguard and negotiate a conditional surrender, in what is now the Royal Oak pub.

Tate wanted his troops repatriated to France rather than face captivity as prisoners of war. Knox refused, insisting that all French troops surrender on Goodwick Sands, near Fishguard, by 10am the following day. If not, he would send the full force of the British army to attack them, claiming thousands were on their way.

With so many of his troops still drunk and the worse for wear, Tate reluctantly agreed. At ten o’clock on 25 February, Tate’s men marched down to Goodwick Sands.

Numerous Welsh women gathered to watch – many of them dressed in their local costume of a red tunic, black hat and chest straps that were uncannily reminiscent of the British militia’s bandoliers.

Folklore has it that Jemima Nicholas organised these women to march continuously around Bigney Hill, on the opposite side of Goodwick Sands – a scene which, to the French, would have looked alarmingly like thousands of British troops descending into Fishguard.

It wasn’t until Tate and his men surrendered their weapons on the beach that they spotted the Welsh women in their traditional costumes. Tate realised it was the local women his men had seen scuttling through the countryside, not British soldiers. But it was too late. The last invasion of Britain was over, just two days after it had begun.

Twenty- ve years ago, to mark the bicentenary of the event, a team of 80 volunteer embroiderers created a 30-metre tapestry, just as the Bayeux Tapestry had commemorated the 1066 French invasion. Housed in Fishguard’s Town Hall, it’s a fascinating and humorous recounting of this lesser-known invasion of British shores. Quaint Fishguard is the perfect base for exploring both the Last Invasion locations and the nearby wonders of the Pembrokeshire National Park. These days you’ll nd the locals extremely welcoming (even the ones wielding pitchforks). www.visit shguard.co.uk

Above: A section of the Fishguard Tapestry depicting the Last Invasion of Britain, on display in Fishguard's Town Hall Below: A vintage postcard shows the distinctive clothing worn by local women

For more historic locations across the country, see www.britain-magazine.com