11 minute read

The Big Interview

© DAVID HOCKNEY THE BIG INTERVIEW

David Hockney

Writing exclusively for Artists & Illustrators, author and art critic MARTIN GAYFORD speaks to the great Yorkshire artist about the joys of spring, his enduring inspirations, and how his latest French studio has given him a new lease of life – and cured his limp!

For the last two years, David Hockney has been living in a novel location. From the Hollywood Hills, he’s moved to La Grande Cour, an old farmhouse in the countryside of Normandy, France. It looks, as he says approvingly, like the cottage “where the seven dwarves live in the Disney film… There are no straight lines; even the corners don’t have straight lines”.

David’s life and work, as well as the thoughts that existence in rustic seclusion have brought him, are the subject of a forthcoming book we wrote together, Spring Cannot be Cancelled, published in March by Thames & Hudson.

Because David is an artist who paints and draws for much of the day, every day, this change of place meant, first and foremost, he needed a suitable studio there. Accordingly, before he moved to Normandy in early March 2019 (and immediately after the opening of the Hockney – Van Gogh exhibition at the Van Gogh Museum in Amsterdam), a spacious and airy working space was created for him inside the ancient wooden beams of an old barn on the grounds of his new dwelling.

He was delighted by it. “Right now, I need to be somewhere like this. When I signed the lease on the second Bridlington studio a decade ago, I felt 20 years younger, and the same thing happened here. I feel revitalised. It’s given me a new lease of life. I used to walk with a stick, but since I came here, I’ve forgotten about it!”

David had two studios in East Yorkshire. The first was in the attic of his house near the seafront at

Bridlington; the second – the one he signed that lease for – was located in an industrial estate on the edge of the town. It was huge, more like a film studio than a painter’s workshop. This was conceived and arranged with the enormous pictures he was making at that time in mind by the artist’s principal aide, Jean-Pierre Gonçalves de Lima (known affectionately as J-P). The Norman studio was also devised by Jean-Pierre, but its scale and feeling are quite different.

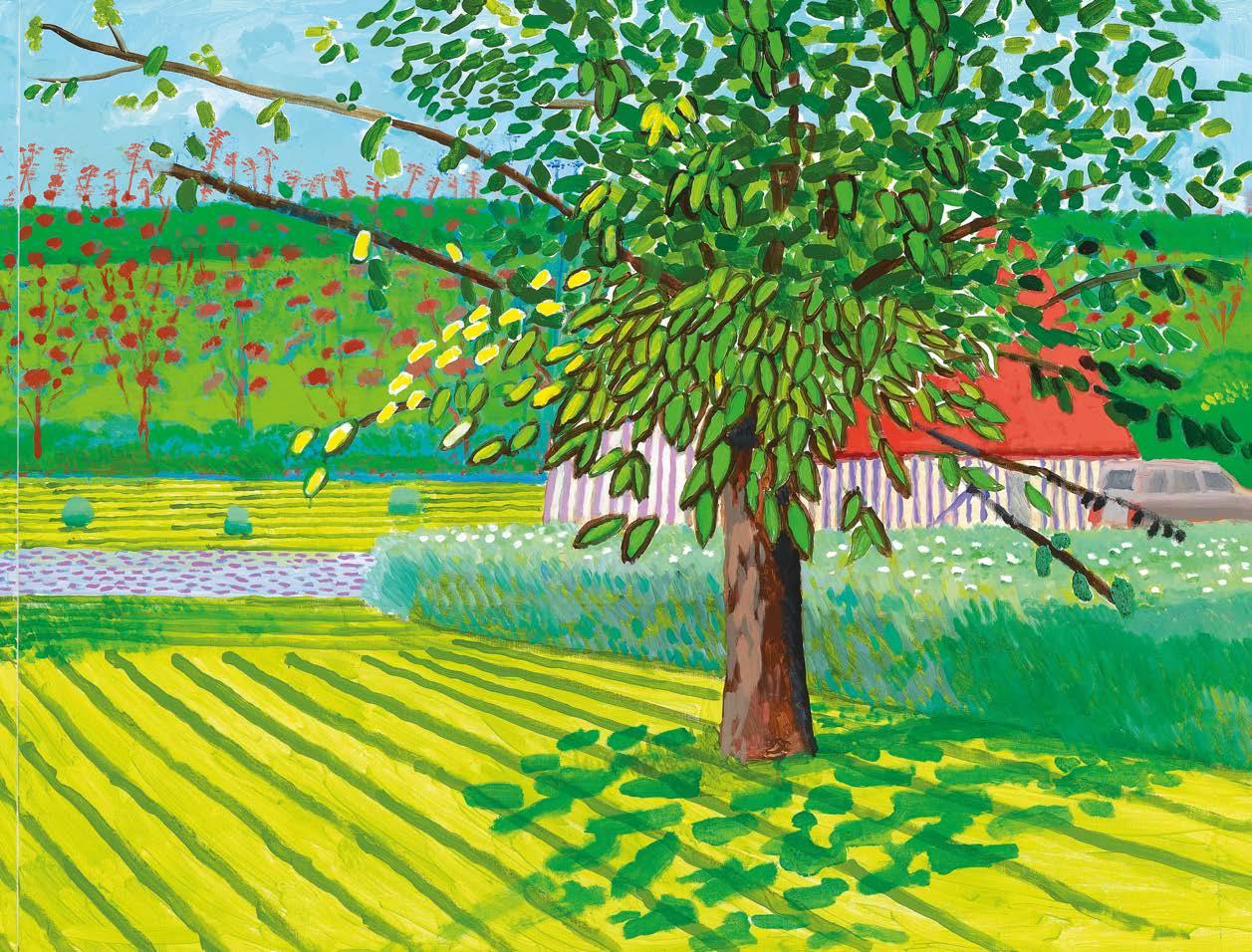

As David explained in the summer of 2019: “When Jean-Pierre first came here, he told me, he realised that we wouldn’t have to drive anywhere, whereas in Bridlington I had to get in the car to go to my subjects. That’s why we got [this studio]. It makes an enormous difference because I get to know the trees a lot better. I’m always looking at them. Always. This afternoon I might draw the apple trees and pear trees again because now they have fruit on them, hanging there.”

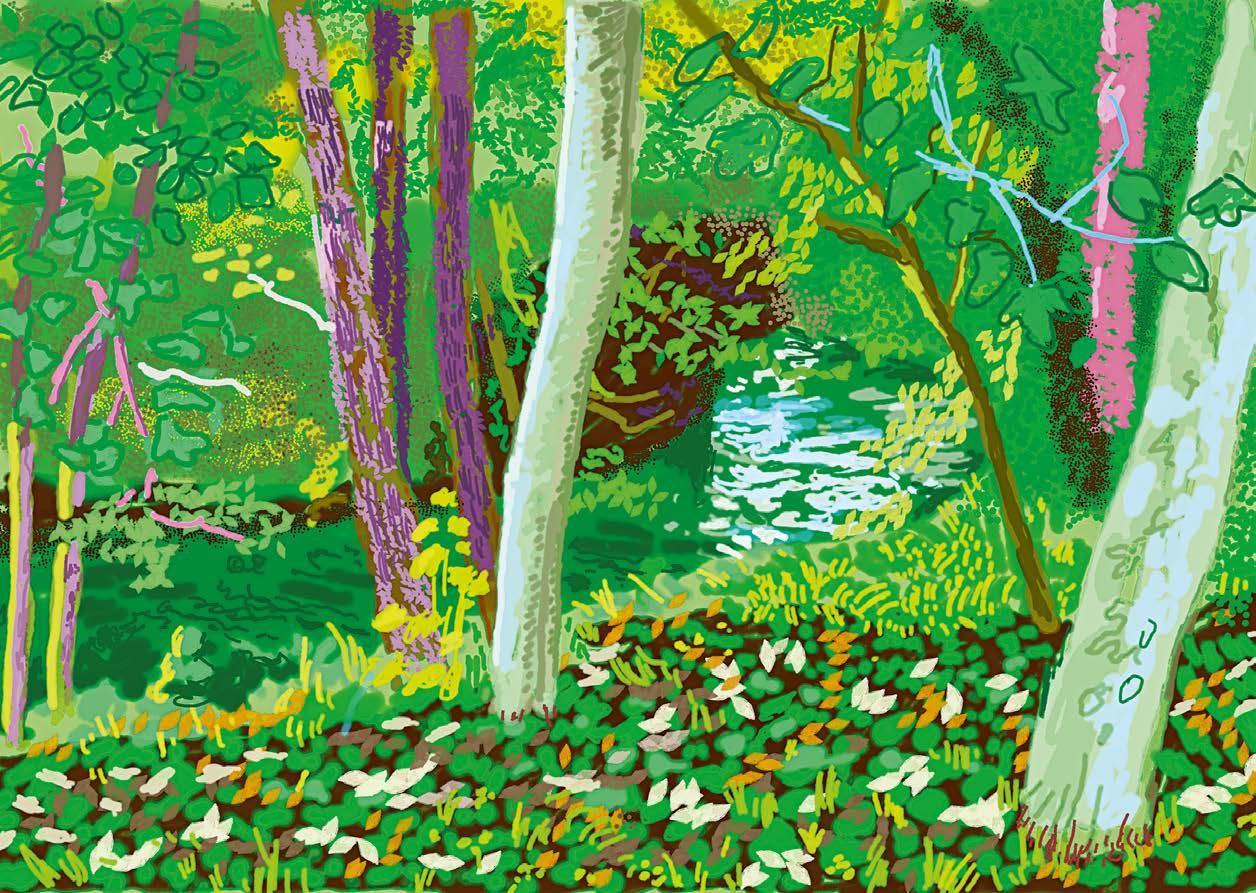

Every artist’s studio is different because it is a reflection of their personalities, habits, and, above all, what they need to do: their work. Some are huge, others tiny; some are orderly, others chaotic. Each of David’s studios that I have seen (this is the fifth) has had its own particular qualities. This new one in the French countryside is a studio immersed in a subject, amongst the trees, in the midst of silence and living plants.

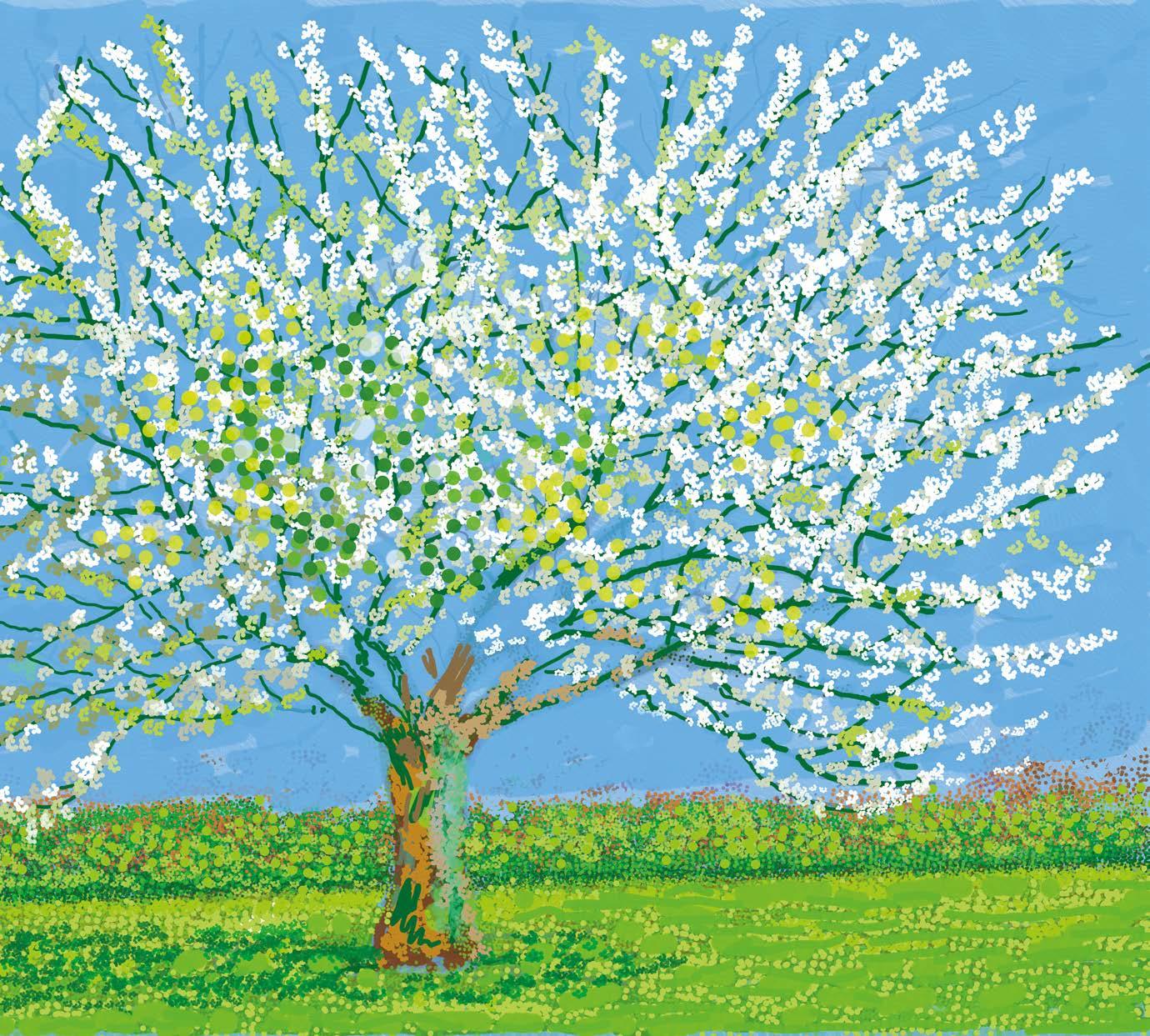

So, the principal models for David’s recent work are growing all around: those apple and pear trees he mentioned are among them. They and others – a favourite cherry tree, for example – feature now in many of his pictures and will soon be familiar to the thousands of visitors who are likely to see The Arrival of Spring, Normandy, 2020, his forthcoming exhibition at London’s Royal Academy of Arts, which opens in May.

“Trees are fascinating things,” observes the artist. “They are the largest plant. Every one is different, like we are; every leaf is different. In Yorkshire, one day a guy asked us why we were always filming the trees; he thought they were all the same.”

These days, David is taking the advice famously offered by Voltaire’s character, Candide, in his 1759 novel of the same name: “We must cultivate our gardens”. However, he is doing so artistically, which makes a big difference.

What a painter finds interesting will not delight every eye (“willows, old rotten planks, slimy posts, and brickwork” were on the great English landscape painter John Constable’s list of his favourite things).

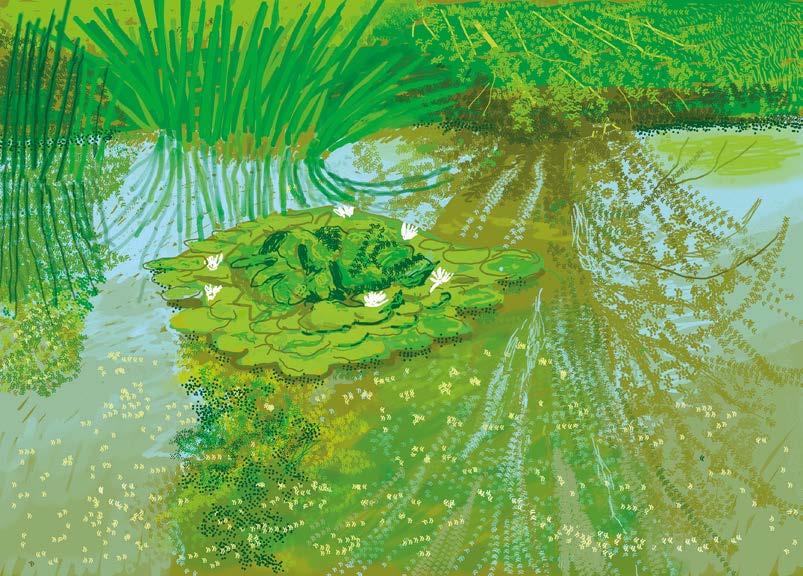

ABOVE David Hockney, No. 180, 11 April 2020, iPad painting

LEFT David in Normandy last spring

PREVIOUS SPREAD David Hockney, No. 599, 1 November 2020, iPad painting

HOCKNEY SPIRIT THREE WAYS TO CREATE, INSPIRED BY THE YORKSHIRE ARTIST

LEARN TO LOOK As a child in Bradford, Hockney would run upstairs on buses, always keen to get the best view. That curiosity has stayed with him throughout his career and much of his work is his way of communicating that time spent looking.

He often tries to do so as simply as possible. Whether painting on canvas or drawing on the iPad, saturated colour is blocked in first, often with a second layer of pattern or texture applied on top. Other details are kept to a minimum, save for occasional contour lines to describe forms and separate colours. TRY SOMETHING NEW Reflecting on his famous 1967 painting A Bigger Splash ahead of a Tate Britain exhibition 40 years later, Hockney concluded that there was no fixed way of making a masterpiece. “If there was a formula, there’d be a lot more memorable pictures,” he joked.

Challenge yourself to try something different with each new painting you make, whether that’s as drastic as changing your whole way of working, or just something simple, such as adding a new colour to your palette. A change will keep you present and engaged, while freshening up the results. PAINT THE WORLD AS YOU SEE IT Although Hockney often relied on his trusty Polaroid camera, he also thought most colour photography was a bit dull. The artist didn’t see colour like that, hence the bright hues in his own work. Colour, like all aspects of painting, is subjective and must be adapted accordingly.

Likewise, Hockney always painted his environment, attaching an importance to his chosen subject in the process. In his eyes, Bridlington is every bit as important as Los Angeles. Staying true to that belief has resulted in great artworks produced with real conviction.

I started drawing on the iPad again. You can make wonderful textures if you build the pictures up in layers

So, arranging a garden for an artist to paint is different from making one for a horticulturalist, a tree fancier, or a lawn lover.

Conversely, what makes for a good painting or drawing is not necessarily the sort of prime specimen that would please a landscape architect or arboriculturalist.

“The three big pear trees are all dead at the top; that’s why there are no leaves on them. But I want to let them stay there like that, because they look like hands clapping or something. It’s the same with those trees with the mistletoe, which kills them eventually. But I think they are wonderful to draw, because they set up a plane. Even in the winter they do.”

After overseeing the conversion of the old barn into a studio, Jean-Pierre went on to oversee the surrounding grounds. Just as the first was tailor-made for David to work in, the latter was arranged specifically for him to depict. In other words, it was a specialised place: a painter’s garden, like Claude Monet’s at Giverny on the other side of Normandy. With this in mind, Jean-Pierre ignored much advice from landscape gardeners, who told him: “This should come out and that should come out; it’s got no value”.

“They want to replace the trees with better, nobler ones,” Jean-Pierre complained. “But I know that for David, visually it’s the shapes and forms that count. He can make a bit of gravel with some weeds growing on it interesting. They don’t see that.”

When the artist began his new life in France in March 2019, he was supercharged by three recent encounters with supreme draughtsmen from the past.

ABOVE David Hockney, The Entrance, 2019, acrylic on two canvases, 91x122cm each

RIGHT Vincent van Gogh, Farmhouse in Provence, 1888, oil on canvas, 46x61cm

FAR RIGHT Joan Mitchell, La Grande Vallée 0, 1983, oil on canvas, 263x200cm

© DAVID HOCKNEY/PHOTO: RICHARD SCHMIDT

FRENCH EXIT FOUR OTHER ARTISTS WHO WENT IN SEARCH OF LA BONNE VIE

VINCENT VAN GOGH The Dutch master’s reputation largely rests on the many masterpieces he created during his final two years in Provence [see 1888’s Farmhouse in Provence, right]. Arriving in Arles in search of light, he found sunflowers and starry nights before his suicide at Auvers-sur-Oise in 1890.

CHARLES RENNIE MACKINTOSH Growing disillusioned with his architecture practice, the Glasgow art nouveau pioneer spent four of his last five years living a peripatetic life in France. He produced more than 40 large graphic watercolours of the local landscape during this period. After his death in 1928, his artist wife Margaret scattered his ashes in Port-Vendres. PABLO PICASSO After enjoying many summers on the French Riviera, the Spaniard eventually moved there, living in various grand villas in Antibes, Vallauris (where he practiced pottery) and Mougins. He was buried privately at the family estate in Vauvenargues.

JOAN MITCHELL The great American Expressionist painter swapped Manhattan for Paris in 1959, later buying a cottage and two-acre estate in Vétheuil, next to where Claude Monet once lived. Though she never loved France unconditionally, the lifestyle suited Mitchell, whose abstract works included the 21-painting La Grande Vallée suite, inspired by a valley in Brittany.

In Amsterdam he had been showing his own work beside that of Vincent van Gogh, while simultaneously there was a glorious exhibition of masterpieces by another of his heroes, Rembrandt van Rijn, at the city’s Rijksmuseum – All the Rembrandts welcomed more than 450,000 visitors. The previous autumn David had made a journey to Vienna to see Once in a Lifetime, a great retrospective of Pieter Bruegel at the Kunsthistorisches Museum.

So, the spring of 2019 was a spring of drawing on paper, often like Rembrandt and Van Gogh, with a reed pen (and using dots similar to the ones Van Gogh was fond of, to represent the gravel paths that Jean-Pierre mentioned).

“There’s a particular line you get from a reed pen,” said David. “Everything makes a different sort of line. And I’ve always enjoyed making different kinds of lines.”

There were affinities in the kinds of marks he was making with the works of both of those great Dutch artists. But there were also fresh, and characteristic, Hockney ingredients: several of the drawings he made were 360-degree panoramas, executed on sketchbooks which pulled out like a concertina. And they were often drawn not in black or sepia, but in coloured inks.

By 2020, however, David returned to the iPad, a medium of which he famously made great use around a decade ago. He explained the change to me in an email at the beginning of last spring: “I have started drawing on the iPad again as Jonathan [Wilkinson, Hockney’s assistant in all technical matters] has got a man in Leeds to make a new version of the Brushes app, which I think is very good, even better than the previous one, which is now unobtainable.” With the iPad, the artist found, “you can make wonderful textures if you build [the pictures] up in layers”.

Shortly afterwards lockdown descended on us all, but Hockney was undismayed. Indeed, he thrived on the consequent lack of interruptions and opportunity for deep concentration. By the end of spring, he had created a hundred works using the enhanced range of effects offered by his improved iPad app. By the end of the year there were 200 – and still they keep appearing. The harvest from the Norman farm has been marvellously fruitful.

David thinks so too. “I think these iPad works are much better than the last lot I did. There is more detail in them; I’ve done it more thoroughly.”

Just now the 83-year-old artist is poised to begin again in spring 2021. Martin and David’s new book, Spring Cannot be Cancelled: David Hockney in Normandy, is published by Thames & Hudson. www.thamesandhudson.com. The Arrival of Spring, Normandy, 2020 runs from 23 May to 26 September at the Royal Academy of Arts, London. www.royalacademy.org.uk

ABOVE David Hockney, No. 316, 30 April 2020, iPad painting

TOP RIGHT David Hockney, No. 556, 19 October 2020, iPad painting

LEFT David contemplates his latest canvas with Ruby the dog in his Normandy studio

RIGHT David Hockney, No. 340, 21 May 2020, iPad painting

© DAVID HOCKNEY/PHOTO: JEAN-PIERRE GONÇALVES DE LIMA

Trees are fascinating things… Every one is different, like we are – every leaf is different

© DAVID HOCKNEY

READER OFFER

Spring Cannot be Cancelled: David Hockney in Normandy is an uplifting manifesto that affirms art’s capacity to divert and inspire. It is based on a wealth of new conversations and correspondence between Hockney and the art critic Martin Gayford, his long-time friend and collaborator.

Artists & Illustrators readers can enjoy 25% off the cover price, a saving of £6.25. Simply use the code CHELSEA25 at www.thamesandhudson.com