CITIZEN’S

CITIZEN’S

PREPARED BY WATER EDUCATION COLORADO

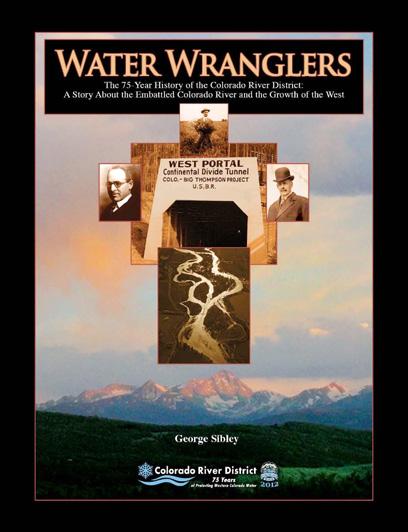

This Citizen’s Guide to Colorado’s Transbasin Diversions is part of Water Education Colorado’s series of educational booklets designed to provide Colorado citizens with balanced and accurate information on a variety of water resources topics. There are now 10 books in the series covering: Colorado water law, water quality, climate change, water conservation, interstate compacts, water heritage, Denver Basin groundwater, where your water comes from, and Colorado’s environmental era. View or order any of these online at www.yourwatercolorado.org.

Water Education Colorado thanks the people and organizations who assisted in the preparation and review of this guide.

Author: Caitlin Coleman

Editor: Jayla Ryan Poppleton

Design: R. Emmett Jordan

Maps by Charles Chamberlin

Research Associate: Brian Devine

GIS support provided by Carolyn Fritz/Colorado Water Conservation Board

Copyright 2014 by Colorado Foundation for Water Education DBA Water Education Colorado ISBN 978-0-9857071-1-8

All photographs are used with permission and remain the property of the respective owners. All rights reserved. Cover photo of the Alva B. Adams Tunnel by Jim Richardson, inset images by (top to bottom) Echo Canyon River Expeditions, Kevin Moloney, Jenny Downing, Northern Water.

Eric Hecox

President

Gregory J. Hobbs, Jr.

Vice President

Scott Lorenz

Secretary

Alan Matlosz

Treasurer

Gregg Ten Eyck

Past President

Rep. Jeni Arndt

Rick Cables

Nick Colglazier

Lisa Darling

Jorge Figueroa

Greg Johnson

Dan Luecke

Mara MacKillop

Kevin McBride

Kate McIntire

Reed Morris

Lauren Ris

Travis Robinson

Sen. Jerry Sonnenberg

Laura Spann

Chris Treese

Reagan Waskom

Jayla Poppleton

Executive Director

Jennie Geurts

Director of Operations

Stephanie Scott

Leadership and Education

Program Manager

Sophie Kirschenman

Education and Outreach

Coordinator

Alicia Prescott

Development Coordinator

Caitlin Coleman

The mission of Water Education Colorado is to promote increased understanding of water resource issues so Coloradans can make informed decisions. Water Education Colorado is a non-advocacy organization committed to providing educational opportunities that consider diverse perspectives and facilitate dialogue in order to advance the conversation around water.

Headwaters Editor and Communications Specialist OFFICES

1750 Humboldt Suite 200 Denver, CO 80218

(303) 377-4433

YOURWATERCOLORADO.ORG

Colorado is a state of boundlessness. From the high plains to the high peaks, nourishing valleys, Colorado Plateau or barren open spaces full of sky, Colorado feels like a place of plenty. Yet the state’s water story is one of scarcity. It’s a story of stretching and making the most of a limited resource, planning for the future, and putting available water to beneficial use. It’s a story of engineering feats, policy, American history and changing cultural values. And it’s a story complicated by geography.

As a semi-arid state that straddles the Continental Divide, meeting demand with water supply has always been a challenge in Colorado. Rarely is there enough water to satisfy all desires. About 80 percent of Colorado’s water falls and flows on the West Slope of the Divide, according to the Colorado Division of Water Resources, while nearly 90 percent of the population lives on the East Slope. The water is not naturally in the same place as the more fer-

tile land, longer growing season or majority of people.

Still, for years people have dug their way out of and engineered around this challenge by diverting water and channeling the resource to where it’s needed. Coloradans have relied especially heavily on the mighty Colorado River Basin, to which all of the West Slope’s rivers are tributary, and used the river’s water, both in-basin and through transbasin diversions, to meet

statewide water needs. Transbasin diversions have helped Colorado make the most of its Colorado River water allocation by moving it around the state, or by providing additional storage to maximize its use within its native basin. As much as these projects have benefitted the state, however, they have not been without environmental and economic costs, costs that continue to be considered, negotiated and, in some cases, minimized today.

Colorado is home to the headwaters of four major rivers: the Platte, the Arkansas, the Rio Grande and the Colorado. As snow falls and melts in the peaks that physically divide the state, water flows down from the mountains through these rivers, traveling east, south or west toward the Atlantic and Pacific oceans. Each river is the deep conveyance point of its basin. If precipitation falls on a hill near Buena Vista, it will eventually find its way to the Arkansas River; if it rains on a farm in Greeley, that rainwater will flow into the South Platte River.

But geography isn’t quite that simple. Each of the major river basins is composed of smaller creeks and rivers that eventually converge, and those tributaries all have watersheds of their own. Look at southwestern Colorado where McElmo Creek, along with the Mancos, La Plata, Animas, Pine, Piedra, San Juan and Dolores rivers all flow from Colorado into New Mexico or

Utah, where they eventually meet the Colorado River. They are all part of the greater Colorado River system, but each has its own unique basin. One basin may receive relatively abundant precipitation, while the next basin might be dry; one might have superb soil or a beautiful hospitable landscape, while another is uninhabitable—the distinctions list on.

Nearly all water diversions, with the exception of newer recreational in-channel diversions for whitewater parks, remove water from its natural course or location and channel it elsewhere. Water might be diverted through a small irrigation ditch, pipeline, reservoir or well. After it’s used, a portion of the water applied to the ground or run through a water system travels back to the river in the form of return flows.

Transbasin diversions—sometimes called transmountain diversions—also divert water, but they cross watershed boundaries, drawing water from one stream or river into the watershed of another. Some of these diversions move water from one sub-basin to another within a greater river system. Or smaller still, many diversions move water from one watershed to another, leaving that water within its native basin and sub-basin. Some refer to all watershed-crossing diversions as transbasin diversions without distinguishing between those that cross major river basin boundaries and those that cross sub-basin or watershed boundaries.

In this guide, we identify transbasin diversions as those that move water from one

Twin Lakes Reservoir, located 13 miles south of Leadville on Lake Creek, was a natural lake enlarged and impounded by Twin Lakes Dam in 1935 as part of the Twin Lakes Reservoir and Canal Company’s Independence Pass Transmountain Diversion System. In the late 1970s, the reservoir was further enlarged as part of the Fryingpan-Arkansas Project to a capacity of 141,000 acre-feet. Water from Twin Lakes is delivered into the Arkansas River and reaches as far as Sugar City, 220 miles downstream.

Through a transbasin diversion, water that was once headed toward the Gulf of California down the Colorado River, for example, might be diverted into the South Platte River Basin and used to irrigate crops or to water a suburban lawn.

of the state’s four major river basins into another, thus interrupting the flow of water from its primary natural course. Water that was once headed toward the Gulf of California down the Colorado River, for example, might be diverted into the South Platte River Basin and used to irrigate crops or to water a suburban lawn. The portion of that water that would have returned to the Colorado in the form of return flows instead goes to the new river, in this example the South Platte, to run east and south to the Gulf of Mexico.

If that water had been used through a traditional in-basin diversion, the return flows could have been appropriated under another water right to be used elsewhere in the Colorado River Basin—downstream water users would then be entitled to those flows. Instead, with a transbasin diversion nobody else owns the rights to expect this water’s flow. As a result, the water can be fully used “to extinction” in the new river basin. Because transbasin diversion water is considered fully consumable, it opens opportunities for receiving basins to implement recycling and reuse programs, stretching water supplies for municipalities or industries, or to apply water to fully consumptive uses such as some oil and gas development practices.

It sounds dramatic, changing the flow of water from its natural course, and it can be, particularly when looking at the effects some of these diversions leave in their wake. Headwaters counties, for instance, which are physically closest to the Continental Divide, have been most heavily tapped for their water—it doesn’t have far to travel or require as much pumping when it’s diverted from the high headwaters regions to cross

the Divide. These basins of origin and their environments have suffered water quality and aquatic habitat issues, exacerbated by transbasin diversions and the resulting reductions in streamflows, ranging from high water temperatures to endangered fish species impacts.

Still, transbasin diversions are common, and Colorado’s earliest transbasin diversions weren’t major projects, but rather small ditches shoveled between two basins. Those who dug these early diversions for placer mining or irrigation intuitively channeled water from a place of plenty to one of scarcity.

That’s how the story of transbasin diversions begins, as well as early Colorado water law. The famous Coffin v. Left Hand case not only cemented the doctrine of prior appropriation in Colorado, it legally allowed for transbasin diversions, which are now inherent in the state’s water law.

Left Hand Ditch was built in 1860 as an irrigation ditch off of Left Hand Creek. During a dry summer, ditch users went searching for water upstream where they found a low ridge separating their dry creek from the wet South St. Vrain Creek. They dug a ditch to divert water from the St. Vrain to Left Hand Creek, moving water from one sub-basin to another, and filed for water rights. When, in 1879, farmers near Longmont found the St. Vrain running dry and no longer delivering water to their land, they discovered Left Hand Ditch taking all of the St. Vrain’s water and reacted by tearing out part of the diversion dam. Within a month, the Left Hand

The tradition of transbasin diversions in Colorado is an old one indeed. The Ewing Ditch dates from 1880—less than 30 years after the first recorded water right in Colorado—and is the oldest project in the state still operating in its original form. The ditch flows over Tennessee Pass between Eagle and Lake counties, transporting up to 2,400 acre-feet of water from the headwaters of the Eagle River, a tributary of the Colorado River, to Tennessee Creek, a tributary of the Arkansas River. The project was first built by the Otero Canal Company to supply supplemental irrigation water to farmers in southeastern Colorado. The Pueblo Board of Water Works purchased the ditch and its water in 1955 and now operates the ditch as part of its regular municipal supply. Water from the Ewing Ditch helps supply almost 40,000 households in the city of Pueblo, and is sometimes leased for irrigation or augmentation purposes to other East Slope users.

Ditch Company prepared a lawsuit against St. Vrain farmers for the damage. The case reached the Colorado Supreme Court, which in 1882 ruled in favor of Left Hand, finding that the right to water is established by the priority of appropriation, not by riparian proprietorship. In other words, water rights are not tied to land ownership along a stream but to appropriation from the stream for use where the water is needed. The first water user to establish a right to divert water has a right to continue diverting and using it wherever he or she is applying it beneficially.

Although this case only dealt with moving water from one sub-basin to another, both within the greater South Platte drainage, it was the first reported case to rule on an outof-basin diversion project. Many years later, in 1961, in a decision on the export of water from the Colorado River Basin to meet metropolitan suburban needs, the Colorado Supreme Court affirmed, “We find nothing in the [state] constitution which even intimates that waters should be retained for use in the watershed where originating.” Water can be moved across boundaries, be they property lines, watersheds, sub-basins or major river basins.

Relying

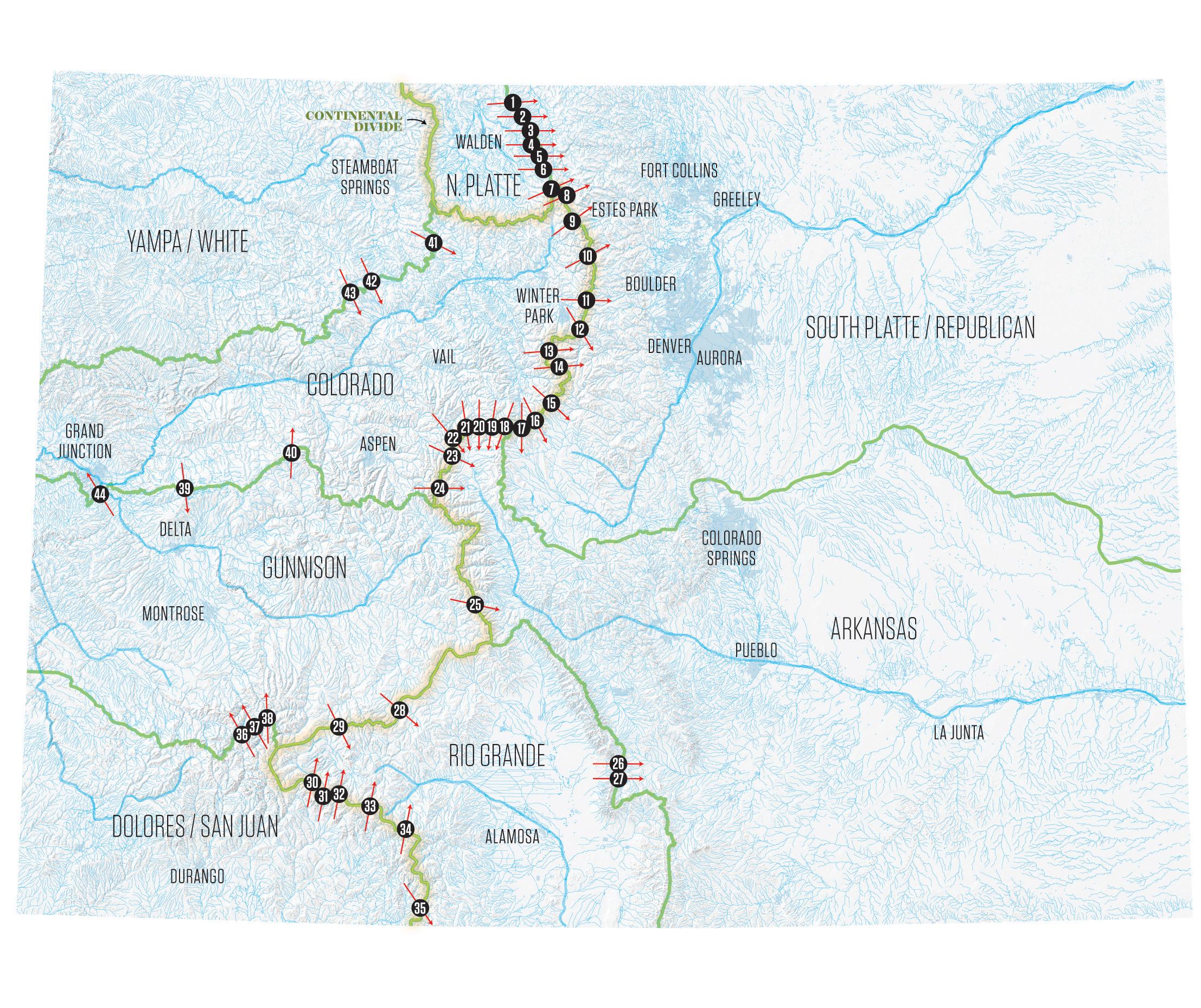

Today many Coloradans depend on transbasin diversions. There are 44 diversions in the state that together move more than 1.6 million acre-feet of water each year from native basins to receiving basins. Of these, 27 are considered transbasin diversions as we have defined them, together transporting around 580,000 total acre-feet of water annually from one of Colorado’s four major river basins to another, with one, the San Juan-Chama Project, crossing state lines.

On both the East and West slopes, Colorado’s landscape and economy are completely different than they would be without transbasin diversions. Although most of these projects were originally constructed for irrigation or municipal use, they now help meet an even wider variety of water supply needs.

Irrigated agriculture, a primary driver for many early diversions, has shaped Colorado’s ecology, economy, culture and growth. When the Northern Colorado Water Conservancy District and the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation built the ColoradoBig Thompson Project, or the Twin Lakes Project was constructed in the Arkansas Basin, the transbasin diversion water made higher-yielding crops possible and provided late-season flows to use for irrigation longer into the growing season.

Today, in the South Platte Basin alone an average of 426,000 acre-feet of water is imported each year, supplementing the river’s native flow of about 1.5 million acrefeet annually. Throughout the South Platte Basin, about 830,000 acres are irrigated on a regular basis, says the Colorado Water Institute. Of those, approximately 640,000 are served by the Colorado-Big Thompson Project’s deliveries of Colorado River water, according to the Northern Colorado Water Conservancy District. Meanwhile, in the Arkansas Basin the Colorado Division of Water Resources reports a little more than 100,000 acre-feet of water being imported annually, supplementing the irrigation of 214,600 acres.

At the same time, successful markets for Colorado’s agricultural products depend on a successful metropolitan economy, which also relies on water from transbasin diversions. In 2007, sales of Colorado goods and services totaled $450 billion, of which $387 billion, or 86 percent, originated from the Front Range, according to a 2009 Front Range Water Council report “Water and the Colorado Economy,” by Summit Economics and the Adams Group. Meanwhile, western Colorado exports about 28 percent of its goods and services to the Front Range, and central Colorado—Gilpin, Clear Creek, Lake, Park, Chaffee, Freemont, Cutler and Huerfano counties—exports 45 percent of its goods and services to the Front Range.

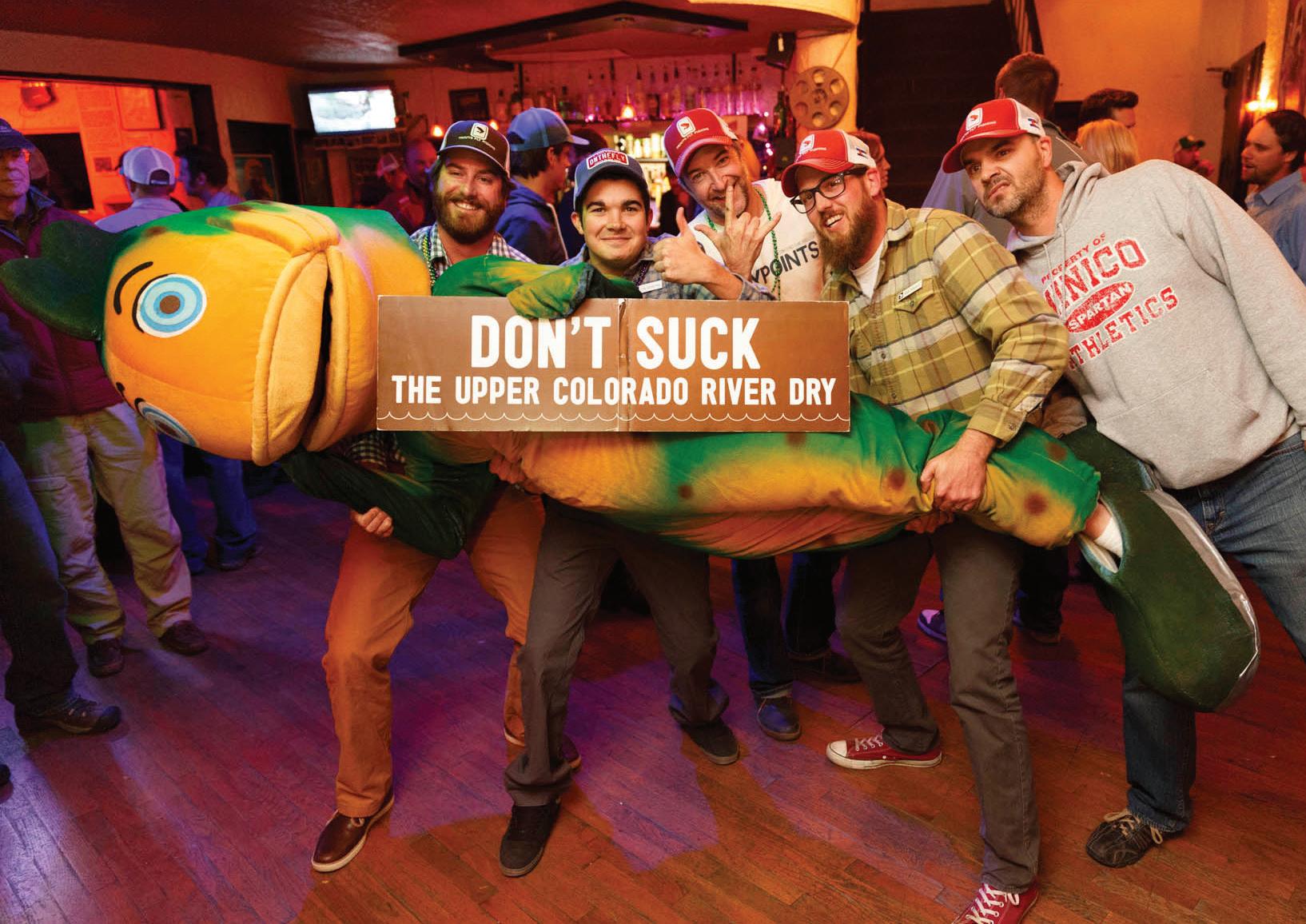

Likewise, Front Range development relies on healthy headwaters communities and economies, and those headwaters communities depend on sufficient streamflows to fuel tourism. Tourism is a primary industry in high mountain towns, comprising 48 percent of all jobs in these communities versus 8 percent of all jobs statewide. Yet, recreation in these places generates as much or more economic impact for the Front Range, according to a 2011 report by the Northwest Colorado Council of Governments. Everything from fishing and rafting to snowmaking or the beauty of mountain streams depends on flows, which if overly compromised would cause those high country communities to suffer. Many feel the environment already has suffered due to the extent transbasin diversions deplete river flows in the headwaters region. Today, transbasin diversions are operated to be more cognizant than ever before of the benefits of keeping water in streams rather than removing it. New agreements provide frameworks for operating transbasin

They may not transport water across the Continental Divide, but several major projects in Colorado move water between watersheds or sub-basins. The Dolores Project is one of these, and it’s the most recent large transsub-basin diversion built as primarily new construction. It stores and moves 90,000 acre-feet of water on average each year from the Dolores River to the San Juan Basin, both within the greater Colorado River Basin in southwestern Colorado.

The Dolores Project’s infrastructure isn’t 100 percent new. The Montezuma Valley Irrigation Company owned an old trans-subbasin diversion that pulled water from the Dolores, dating back to 1889, for irrigation. That original diversion made possible the town of Cortez and farming southeast of the river, but didn’t have significant accompanying storage. Expanding that original diversion was long a topic of interest, but was only seriously considered in 1977 when President Jimmy Carter got behind the project to settle Native American water rights claims in southwestern Colorado.

Negotiations to resolve the Colorado Utes’ claims in the early 1980s involved the tribes, water conservancy districts and the state. At the same time, construction began on the Dolores Project’s McPhee Reservoir. The Ute Water Rights Settlement was agreed upon in 1986, the same year McPhee Reservoir was filled, and in 1988 Congress ratified the agreement. In 1994, municipal and industrial water flowed to the Ute Mountain Ute reservation. The communities of Cortez and Dove Creek also received water from the project, as did much of Montezuma and Dolores counties.

The Animas-La Plata Project was also negotiated in the 1980s in correlation with tribal water rights. Under the plan at the time, the Animas-La Plata Project would provide irrigation as well as municipal and industrial water to tribes and non-Indian entities by diverting water from the Animas to the La Plata Basin. But due to budgetary and environmental concerns, the project was downsized: There would be no pipelines transporting water to the La Plata Basin and no irrigation component. In 2007, Ridges Basin Dam was completed and Lake Nighthorse, the resulting reservoir for the project, filled in 2011 in the Animas Basin. Although not constructed as the trans-sub-basin diversion project it was conceptualized to be, components of the full Animas-La Plata Project continue to come online such as Long Hollow Reservoir, just east of the La Plata River, which can be used for irrigation water. A potential pipeline and pumping plant to serve two subdivisions in the La Plata Basin has also been discussed—if completed, this would transport a small supply of trans-subbasin water for domestic use.

1902 Bureau of Reclamation is established

diversions and reservoirs in ways that enhance river environments or provide additional water for recreation.

Another shift is that, in many cases, the water these projects deliver serves more thirsty cities while providing less water to agriculture. The Colorado-Big Thompson Project, completed in 1956 to serve growing agricultural water demand in northeastern Colorado, for example, delivered 97 percent of its water to agriculture in 1957, when the project made its

first deliveries. But in recent years, about 60 percent of all Colorado-Big Thompson water goes to agriculture, while 40 percent now serves municipal and industrial uses. Likewise, the Twin Lakes Project was constructed in the 1930s to provide supplementary transbasin water to farmers along the Colorado Canal in the Arkansas Basin, but today Colorado Springs Utilities holds about 62 percent of the water and Aurora Water owns about 5 percent.

For Denver Water, which serves about 25 percent of the state’s population, transbasin diversions will comprise 50 percent of supply at full build-out. Denver’s large diversions have not only met its growing population’s basic needs for water, but also give city dwellers the pleasure of walking along tree-lined streets and recreating in green parks. More recently, Denver has been focusing more on water conservation and reuse to make the most of its water supplies and minimize the need for additional transbasin diversions. For example, once complete, Denver’s water recycling program will provide more than 15,000 acre-feet of recycled

water per year for industrial use and for irrigation and lakes in the city’s parks and golf courses.

Aurora Water’s Prairie Waters system is also recapturing transbasin water—in exchange for some of the water it discharges, the city pulls from 17 downstream wells along the South Platte River. The water is subjected to natural filtration through hundreds of feet of sand and gravel before being pumped 34 miles back to a state-ofthe-art treatment facility. The treated water is blended with the city’s mountain supply and redistributed. By using the water twice, Aurora boosts its supply by more than 10,000 acre-feet annually—an amount that will reach 50,000 acre-feet at full build-out. With basin-of-origin communities looking to the Front Range to implement comprehensive conservation and reuse strategies to meet future water demand, much more potential remains for using transbasin diversion water multiple times. According to the Metropolitan Water Supply Investigation, future plans for reuse in the Denver metro area alone could provide another 160,000 acre-feet per year by 2050.

With high demand for Colorado’s water, and needs that differ from basin to basin, transbasin diversions have caused tension between receiving basins and depleted basins for more than a century. Water has always been tied to opportunity, and although many diversions were negotiated and impacts mitigated, some issues were not resolved to everyone’s satisfaction, resulting in long-standing grudges and division. Water supply, after all, is critical for every basin’s future health, environment and economy.

As Governor John Hickenlooper said in 2011 when the landmark Colorado River Cooperative Agreement between Denver Water and West Slope water entities was unveiled, “This state has to realize, people in metropolitan Denver have to realize, that their self-interest is served by treating water as a precious commodity and that its value on the Western Slope is just as relevant as its value in the metro area.” The agreement, meant to protect the Colorado River mainstem while allowing Denver to develop future supplies, is one example of recognizing Colorado is just one state—and all basins, and their successes, affect one another.

Transbasin diversion projects—and the opportunities associated with the water they move—have fueled economic growth, allowed population centers to boom, created new recreational opportunities, ensured year-round streamflows, and provided reliable water to receiving basins. But they’ve also brought serious drawbacks, particularly to headwaters communities. Basins of origin have seen reduced streamflows, resulting in recreational and economic concerns, water quality concerns, and more, while at the same time benefitting from additional storage, recreational opportunities and economic benefits provided by reservoirs built on the West Slope as components of transbasin diversion projects. Although Colorado is working on balancing regional concerns within the state’s limited water supply, the effects, both positive and negative, of transbasin diversions statewide are remarkable. And despite a long history of complex water engineering and negotiations that went into building transbasin diversions, Colorado’s quest for effectively managing its water supply continues to be among the state’s highest priorities. n

Part of Aurora Water’s Prairie Waters system, the Peter D. Binney Water Purification Facility (bottom) was completed in 2010, enabling Aurora to reuse 10,000 acre-feet of transbasin water annually, which supplied 20 percent of the city’s demand in 2012. The project will be expanded over time to reuse up to 50,000 acre-feet annually

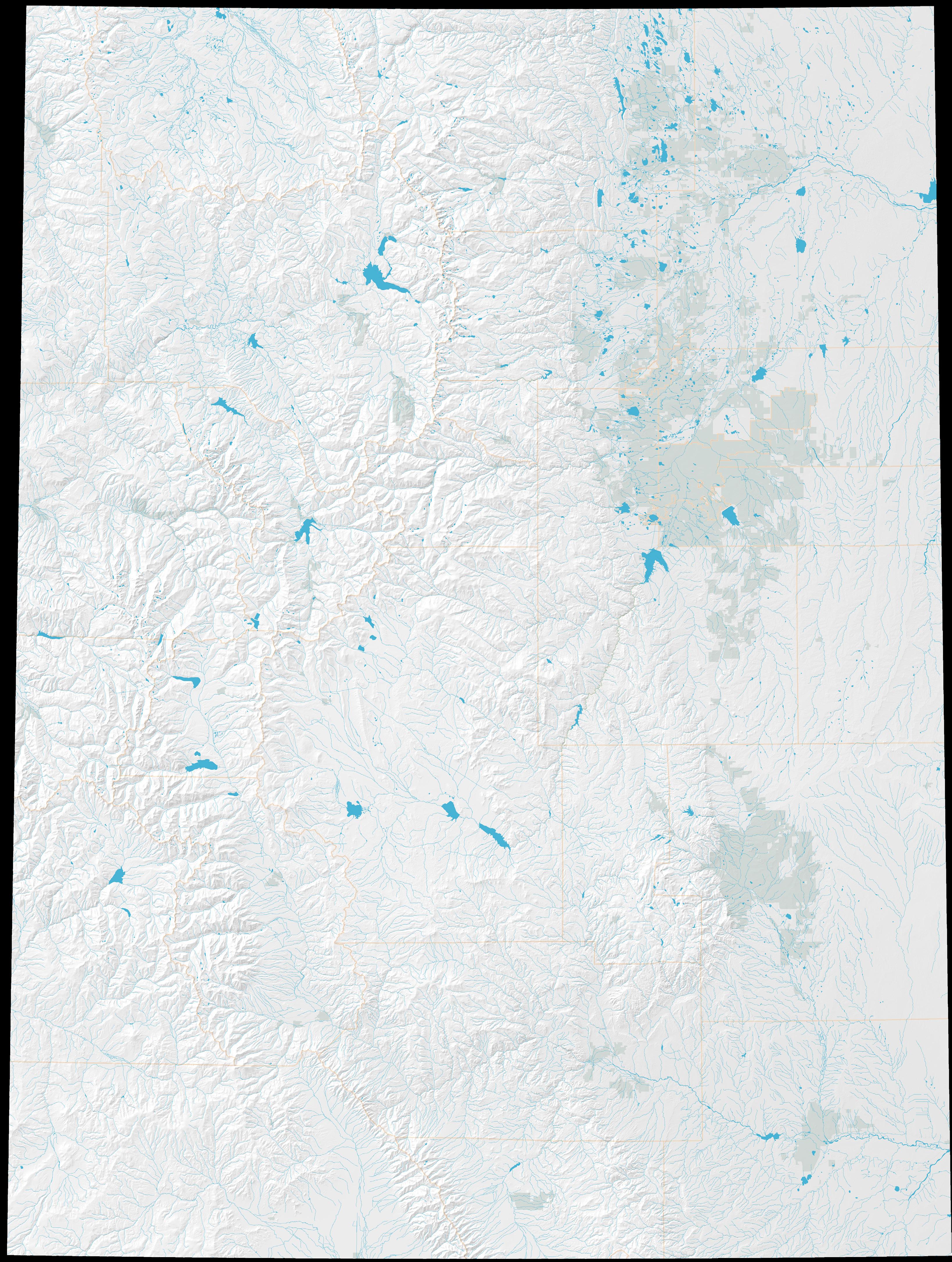

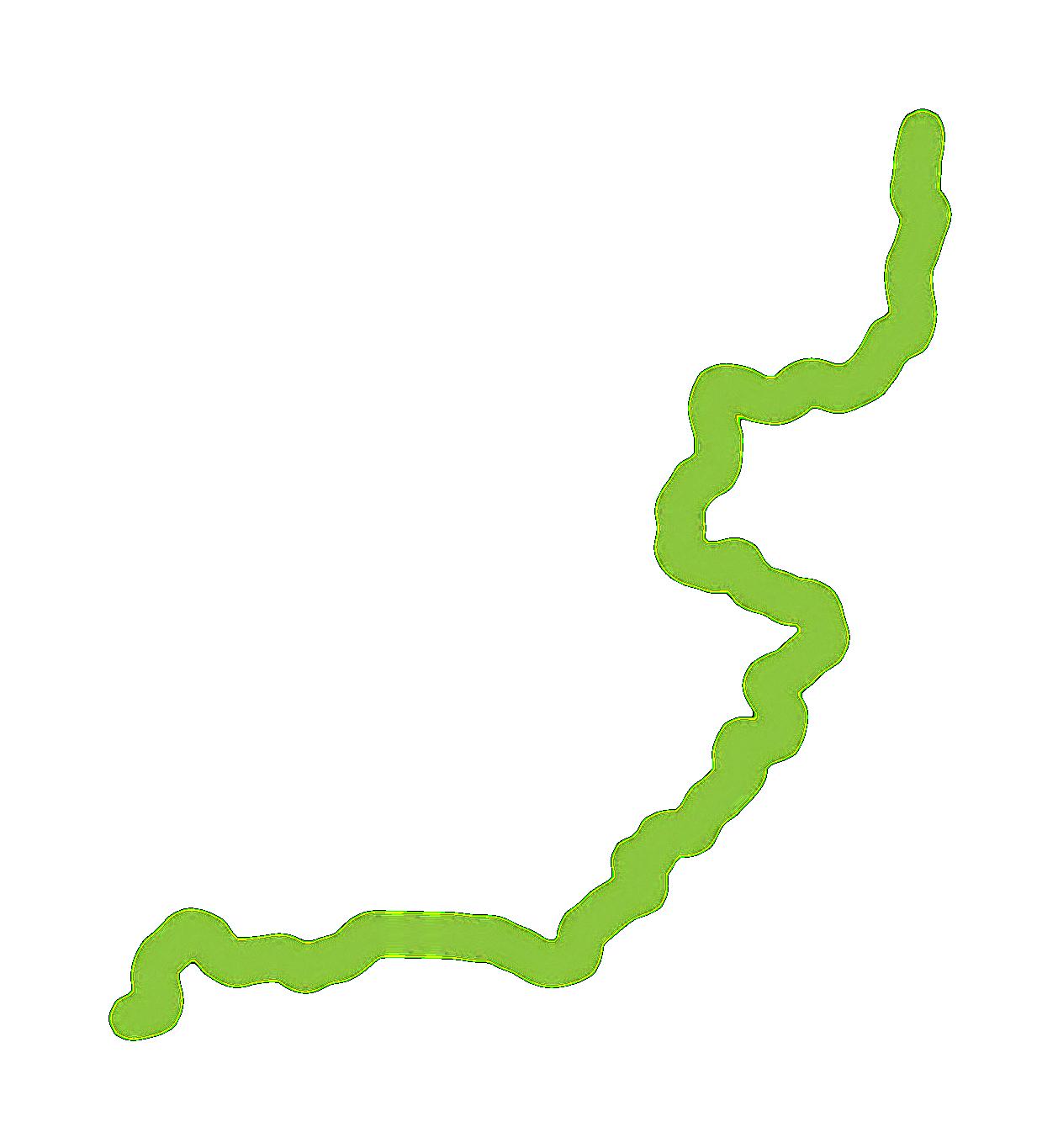

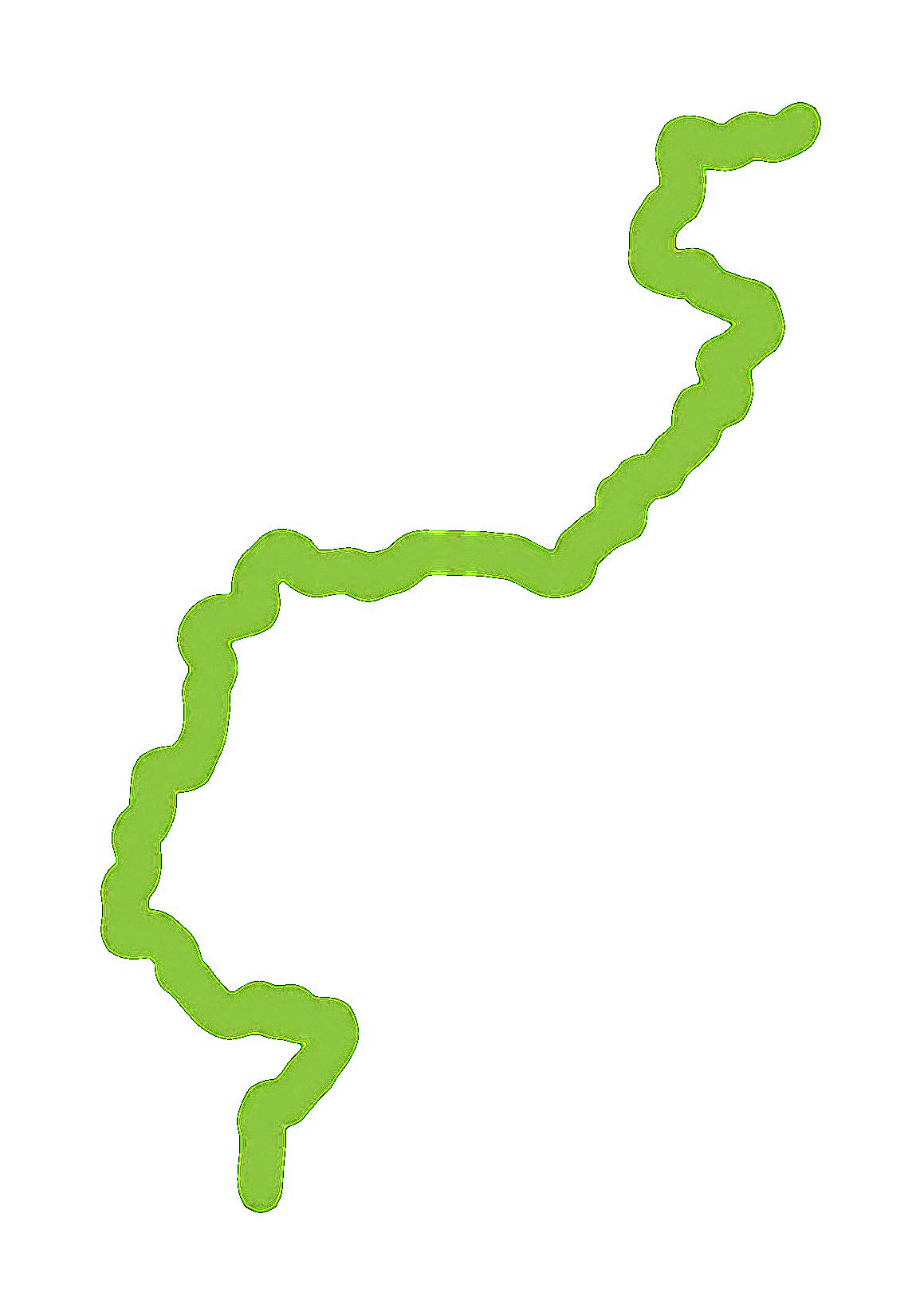

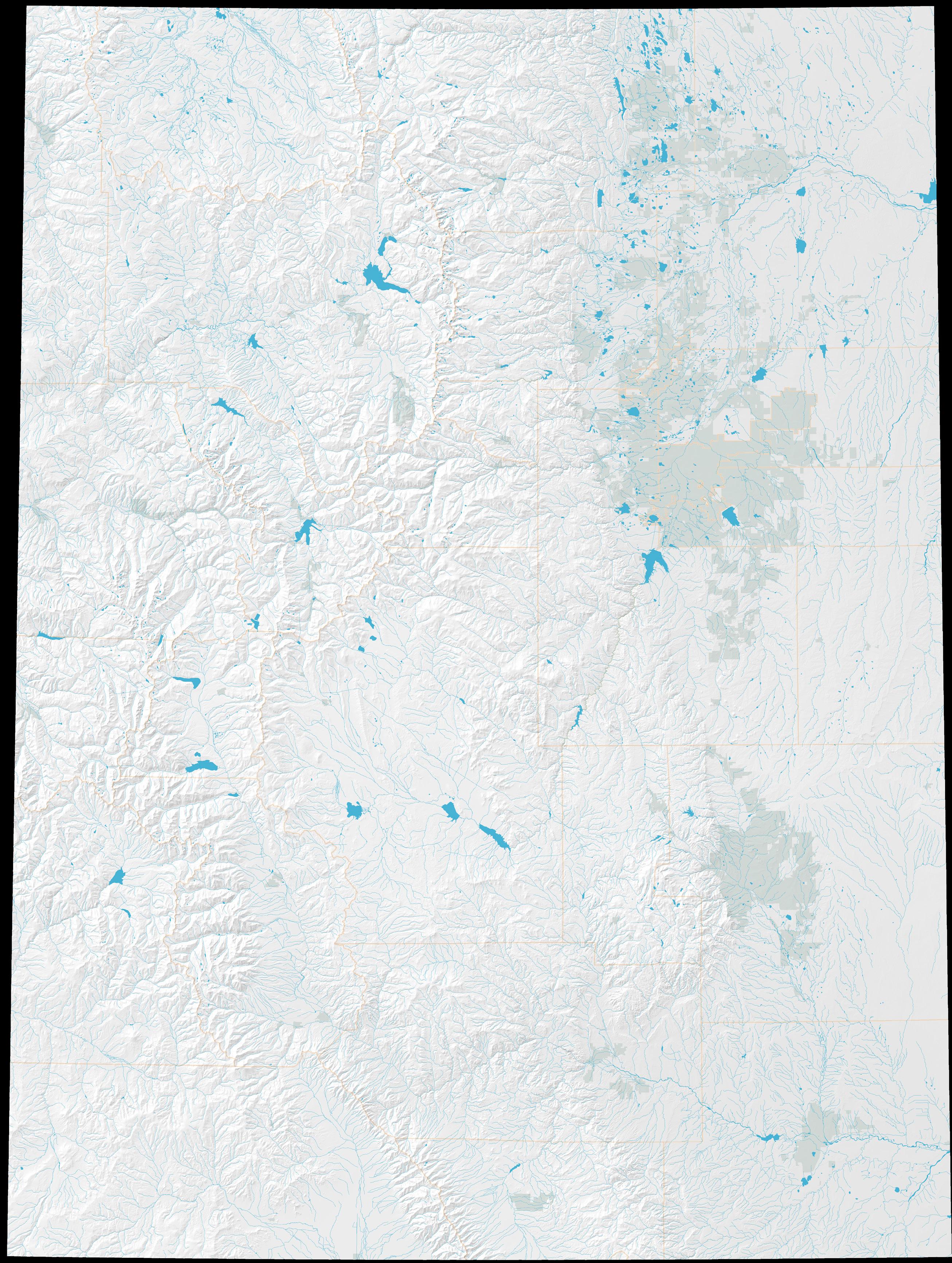

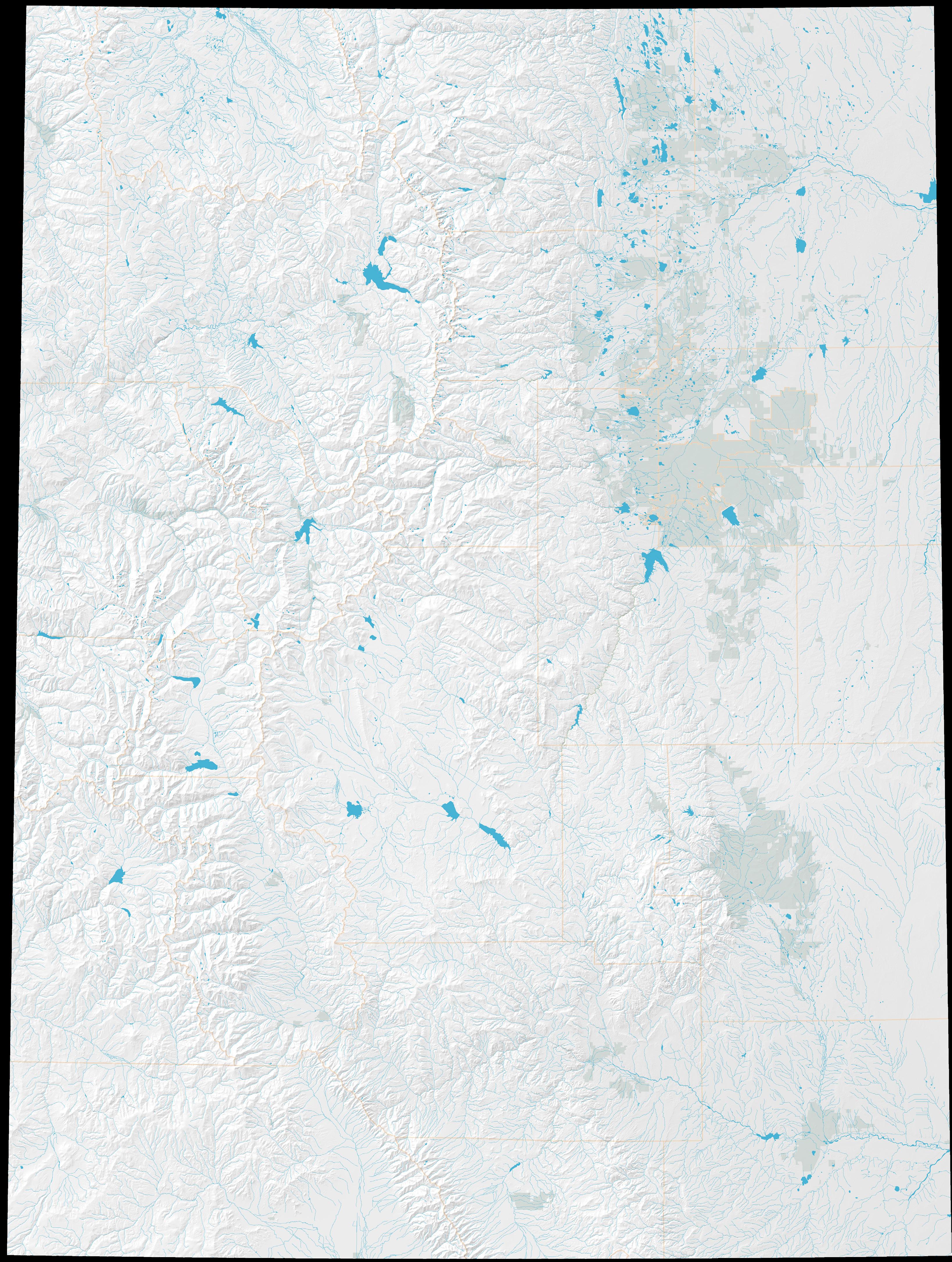

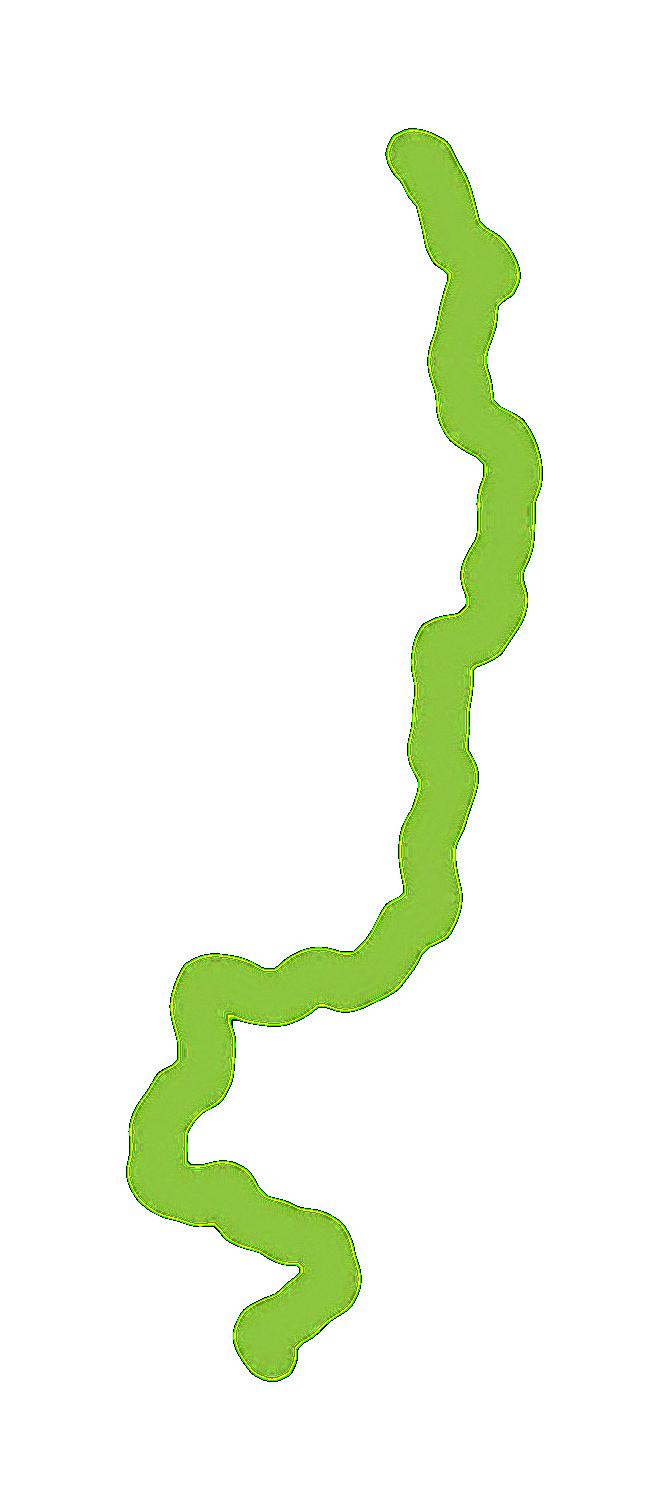

Identified by the arrows above, 44 diversions move water from one of Colorado’s major watersheds, as defined by state administrative water divisions, to another. Of those, 27 are considered transbasin diversions, in that the water they transport crosses between two of the state’s four major river basins: the Colorado (Colorado mainstem, Yampa/ White, Gunnison, and Dolores/San Juan basins), the Platte (North Platte and South Platte/Republican basins), the Arkansas, and the Rio Grande. All but two of these diversions cross the Continental Divide.

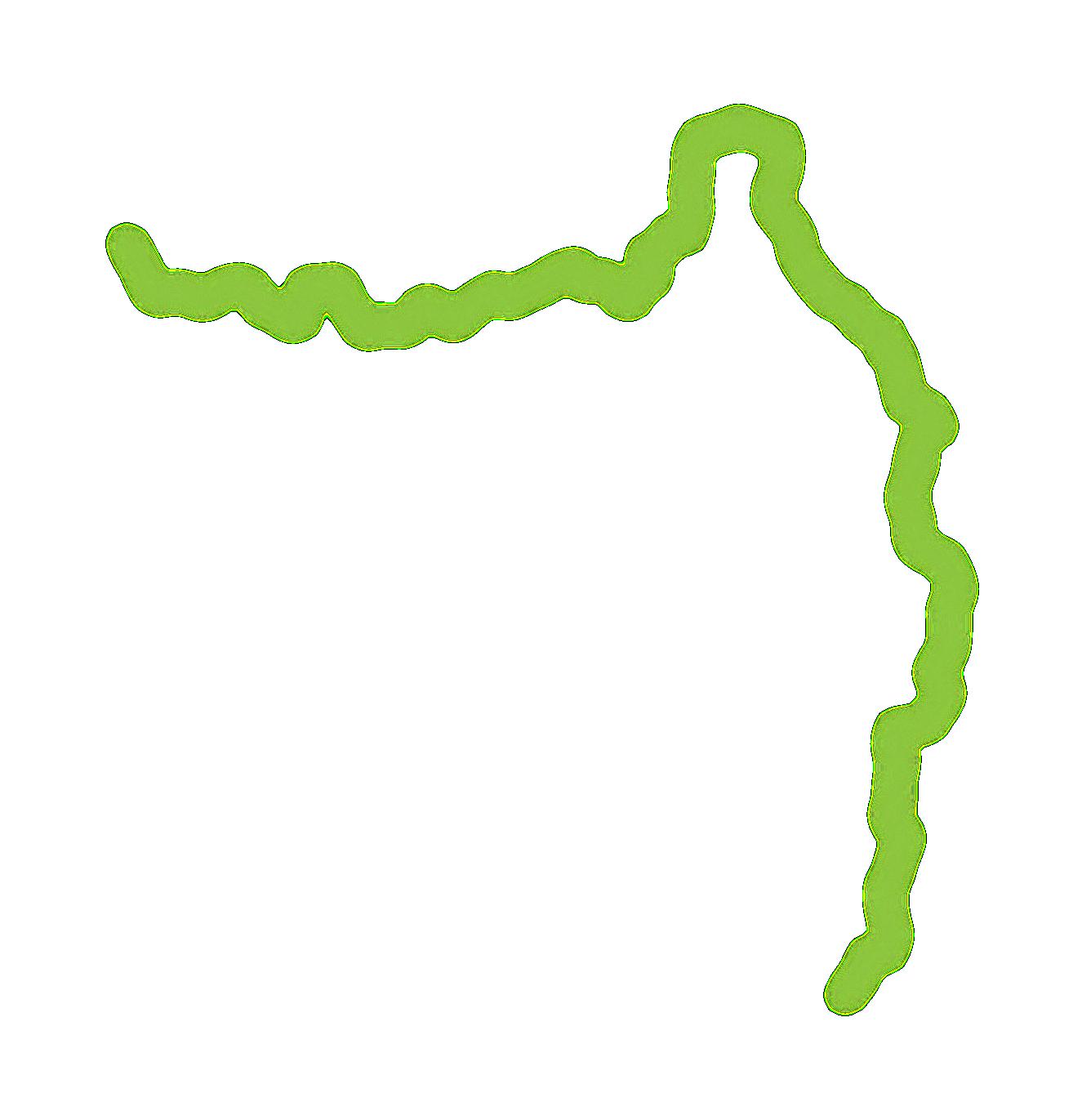

The Continental Divide, shown on the right in red, separates Colorado’s wetter Colorado River Basin on the West Slope from the East Slope’s drier Rio Grande, Arkansas and Platte basins. While West Slope rivers channel around 80 percent of the state’s precipitation, the East Slope harbors nearly 90 percent of the people and just under 75 percent of the irrigated acres.

On June 23, 1957, the Adams Tunnel (inset) carried the first Colorado-Big Thompson Project water under the Continental Divide to East Slope water users, who waited with anticipation. Southwestern Colorado’s jutting San Juan Mountains (below) comprise part of the Continental Divide, which separates North America’s predominant flow of water between east and west.

Colorado’s transbasin diversions weren’t built or agreed upon overnight. Since the state’s earliest development, attitudes have changed, viewpoints have evolved, and policy, along with negotiation, for water supply and transbasin diversion projects has gone through distinctly different but fitting eras.

In semi-arid Colorado, there has always been a need for water engineering to meet demands. The Ancient Puebloans of the Mesa Verde region built diversion ditches and reservoirs, as did Colorado’s early Spanish settlers hundreds of years later in the 1800s. Throughout the 19th century small irrigation ditches gave way to larger community ditches. By 1890, the South Platte River and its tributaries were so heavily appropriated by irrigators that junior water rights were often shut down by late summer because there was not enough water to serve all needs. Most of the Arkansas River bottomlands were also under irrigation, with canals undergoing expansion and new, longer ditches being built to reach as far east as Sugar City in Crowley County. The state’s population was 194,000; Denver was home to 35,000. At the time, there was still little development on the West Slope, so East Slope water users could secure senior water rights on the other side of the Continental Divide and channel it east to meet the needs of their growing populations and crops. Transbasin diversions and plans for diversions became the necessary solution to the puzzle of the East Slope’s water scarcity.

The earliest transbasin diversions were constructed quickly and simply in response to water shortages. In 1882, the Larimer County Ditch Company became one of the first irrigation companies to pursue a transsub-basin diversion across a significant river basin boundary. The company built the Cameron Pass Ditch, which brought water from

Michigan Creek in the North Platte Basin to the Cache la Poudre watershed in the South Platte Basin. The Cameron Pass Ditch was small by today’s standards, only 3 feet wide, 1 foot deep and a half-mile long. Other projects followed, including the well-known Grand River Ditch, where work began in 1894. The Grand River Ditch originated at the headwaters of the Colorado River, then called the Grand River, and delivered water to farms along the Poudre—making it the first transbasin diversion from the Colorado River mainstem. The Grand River Ditch was an engineering marvel at the time, with 8 miles of ditch built by hand across a high mountain pass. By 1936, the ditch extended for 17 miles through Rocky Mountain National Park.

In these early cases, a transbasin diversion was much like any other ditch that diverted water from a river to wet the land where it was needed. It took manpower to shovel a conveyance, and though that was laborious, the diversions were built without further discussion, negotiation or other work beyond obtaining water and property rights. The diverting agency or ditch company would acquire land, build a diversion structure and storage, file for water rights, and put the water to beneficial use. This was all that was required, legally, while the diversions—and basin-oforigin populations—were small. There was no governmental intervention and no leadership besides that of the individual, ditch company, or financing corporation—if someone wanted water they could file for a right and get it.

The era of small projects was short-lived, and the heyday of transbasin diversions was on the horizon. In the 1880s, the state commissioned the first studies to examine the feasibility of building larger projects that could bring more water from the wetter West Slope of the Colorado Rockies. Expanding Front Range agriculture and the arid climate begged for more water. Population growth in the western United States wasn’t slowing either. Colorado’s population more than doubled between 1880 and 1890, growing to 413,000, with 107,000 Denver residents; the state’s population hit 800,000 by 1910 and by 1931 topped 1 million. Railroad companies and newspapers promoted the American West, touting Colorado’s great agricultural potential and the lush luxury of huge crops.

In 1902, the federal government created the Reclamation Service, now the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation, a new agency President Theodore Roosevelt helped conceive to build big water projects and allow the arid West to “reclaim” and fully develop its potential. Within its first few years of existence, the Reclamation Service began investigating a transbasin diversion in Colorado from the headwaters of the Grand River, which would later be renamed the Colorado. Then, and for years to come, the headwaters region would be the target for transbasin diversions because of its easy access just across the Continental Divide.

While East Slope water users were eyeing the Colorado River, so too were other states. Water battles were breaking out around the young West, and Colorado, which encompassed the headwaters of four major rivers—the Platte, Arkansas, Rio Grande and Colorado—sat at the center of it all. Although Colorado was quickly growing, California was growing faster and thirstier. With a large population in the early 1900s and blossoming agriculture in the Imperial Valley, California was already heavily dependent on Colorado River water. While Colorado’s population was just under 800,000 in 1910, California’s was nearly 3.5 million. Colorado officials worried that California’s rapid growth would usurp future water and economic opportunity from Colorado. Although Colorado had adopted the Prior Appropriation Doctrine to allocate water on a first-come, first-served basis within the state, it shared a very real

the nation. All the big water projects that had previously been mere wishful thinking were now discussed and negotiated with the very real thought that funding might actually be available.

ment that some authority or court of equity should take jurisdiction of it.”

This tie between water availability and future growth and opportunity wasn’t new, of course. The same logic led to the 1922

nel, also known as the Independence Pass Tunnel, into North Fork Lake Creek at the headwaters of the Arkansas. There, water is stored in the Twin Lakes Reservoir, south of Leadville, then released and delivered through

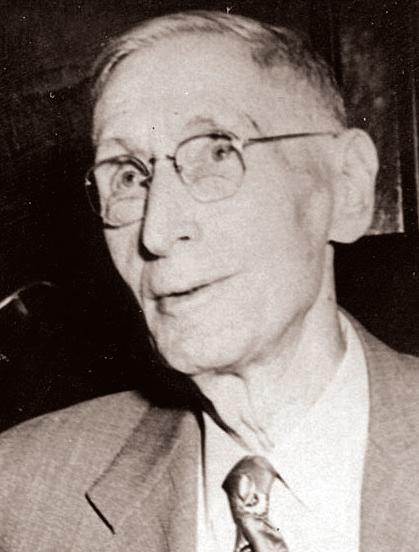

Clifford Stone

Known for his role as the first director of the Colorado Water Conservation Board (CWCB), Clifford Stone was present for the creation of the Delaney Resolution that enabled forward movement on the Colorado-Big Thompson (C-BT) Project in the mid-1930s. He then became a one-term legislator who carried two of the most important water bills of his time, one creating the CWCB and another establishing the Colorado River Water Conservation District. He also collaborated in a trans-Divide drafting committee for the Water Conservancy Act. All three passed in 1937. Stone left the legislature at the end of his term in order to take on the challenge of creating the CWCB. Serving as the agency’s director from 1938 to 1952, Stone dedicated the rest of his life to trying to work out a cooperative vision for all of Colorado based on Senate Document 80 and the spirit that enabled consensus over the C-BT. He envisioned the state working with the Bureau of Reclamation to build a Blue River-Denver project and a Gunnison-Arkansas project, both modeled on Senate Document 80 with the provision of West Slope compensatory storage. He was ahead of his time, though, given the presence of Glenn Saunders at Denver Water who had no intention of cooperating with anyone from the West Slope, and some local naysayers on the West Slope. In this way Stone was a sort of John the Baptist, his voice crying in the wilderness.

Charles Hansen

Known as “the godfather of the Colorado-Big Thompson Project,” Greeley newspaperman Charles Hansen was a consistently impassioned booster of the effort to supplement northern Colorado irrigation with water from the Colorado River. Although he was not the first to call attention to the state’s eponymous river as a source of transbasin water, Hansen used his Greeley Tribune to promote “the Big T” for federal funding as early as 1933. He used his prominence in the community, his extensive political connections, his identity as a newspaperman—as opposed to an irrigator who would directly benefit from the project—and good old-fashioned enthusiasm to win over Western Slope interests, congressmen (especially the long-serving representative of western Colorado, Edward Taylor), and the famously difficult Secretary of the Interior Harold Ickes. After the 1937 approval of the Colorado-Big Thompson and creation of the Northern Colorado Water Conservancy District to operate the project and buy its water, Hansen became Northern Water’s first president. He continued in his role as happy booster of agriculture in northern Colorado until his death in 1953.

Frank Delaney

The man who led the Western Slope through 30 years of conflict and compromise over Colorado River water, rancher and attorney Frank Delaney first made his mark in 1937 as a leader of the Western Slope Protective Association. Convinced that the East Slope’s advantages in population and political power made the Colorado-Big Thompson Project inevitable, Delaney persuaded West Slope water users to agree to a plan that provided them compensatory storage in Green Mountain Reservoir, fearing the project would otherwise eventually be built without any compensation for the West Slope at all. Delaney went on to write the legislation creating the Colorado River Water Conservation District and served as the River District’s general counsel through the negotiations that produced the Blue River Decree and Fryingpan-Arkansas Project. Delaney consistently fought to protect western Colorado water rights and to acquire compensatory storage for transbasin diversions, while encouraging the state to come together to develop its full allocation of Colorado River water in order to secure it against the claims of California and Arizona.

One of the most powerful men ever to represent Colorado in the halls of U.S. Congress, Edward Taylor chaired the House Appropriations Committee during negotiations for the Colorado-Big Thompson Project. Taylor held the federal purse strings and used his position to insist on compensatory storage to protect existing water users as well as future development on his native Western Slope. Taylor’s position was always “an acre-foot for an acre-foot,” reflecting a strong conviction that diverters from across the Divide should build reservoirs for the West Slope equal in capacity to the amount of water they planned to take for themselves. He withheld federal funding for the Colorado-Big Thompson at the height of the Great Depression to obtain his terms, but by 1937 he had fallen ill, and without his participation, the final agreement included less than one-for-one compensation. Although it was not until he approved that the Colorado-Big Thompson legislation ultimately passed the House and Senate that year, Taylor, until his death in 1941, threatened to withdraw funding for the project if the West Slope were marginalized.

1950

one that discussed the establishment of water conservancy districts.

Convening for the second time less than two weeks later, the committee adopted the Delaney Resolution, a four-and-a-halfpage draft that would become the final word on compensatory storage—though it would be two years before this resolution became law. Frank Delaney, a water lawyer and cattle rancher from Glenwood Springs introduced the resolution, modifying Taylor’s previous “acre-foot for an acrefoot” compensation stipulation, which the Northern Colorado Water Users Association argued was financially and physically unreasonable. Instead, if a project was planned and surveyed ahead of time, compensatory storage need only mitigate the project’s expected impacts on present and probable future West Slope development. Although the Delaney Resolution was not unanimously approved, it was adopted and formalized over the next year in Senate Document 80, which presented the Colorado-Big Thompson Project to Congress.

West Slope water leaders may not have wanted any transbasin project, but they recognized they couldn’t legally prohibit diversions from being built and that they lacked critical mass and funding to develop the water themselves. Many saw only one option: to capitalize on opportunity by cooperating with East Slope diverters to obtain compensatory storage.

Negotiations regarding compensatory storage took another year and a half, much back-and-forth and some strong personalities, but in 1937 four related bills emerged, drafted with input from both East and West Slope representatives, that would shape Colorado’s water supply future and provide the first legal mitigation requirements for transbasin diversion project impacts on basins of origin. The Water Conservancy Act, signed into law by Governor Teller Ammons on May 31, 1937, came first, which allowed for the organization of water conservancy districts anywhere in the state. Water conservancy districts would be considered quasi-municipal organizations with taxing power to develop water projects. Next came a bill, on June 1, 1937, creating the Colorado Water Conservation Board, or CWCB, continuing earlier planning efforts to unify the state and gain federal New Deal funding. Judge Clifford Stone, who became the first director of the CWCB, acknowledged that negotiations up to that point had been independently led and organized. Stone said, “The problem is too great to permit of its having any partisan aspect. And this must be true with respect to its administration, that it shall not be partisan in any way whatever. Efficiency and the desire to accomplish something and to utilize

1951 Denver Water Board draws “blue line” boundary around 114-square-mile area in which it will supply water—56 square miles are in city and county of Denver

our water resources must be the watchwords of the program followed.” Hence, a nonpartisan state agency, the CWCB, was badly needed.

A bill creating the Colorado River Water Conservation District was approved by the governor on June 7, 1937, giving legal status to the Western Colorado Protective Association. The Colorado River District was charged not only with protecting and developing West Slope water, but also with safeguarding the state’s Colorado River entitlement for Colorado as a whole. With

taxing authority, it would cooperate with the Bureau of Reclamation in construction of new water projects—though not directly taking on construction—and would coordinate the activities of West Slope counties.

East Slope users benefited tremendously from the new Colorado-Big Thompson Project and a congressional funding appropriation that went through the Bureau of Reclamation. Northern Water negotiated with Reclamation for eight months and agreed to pay a portion of the project cost, up to $25 million. When Northern asked

citizens in its district to approve a tax on themselves, 94 percent of the population agreed. Such nearly unanimous support for imposing a tax is a testament to the benefit people knew would come with the project, which was completed in 1956. The Alva B. Adams Tunnel, which since 1957 has pulled an average of 220,000 acre-feet of water each year from the headwaters of the Colorado River to northeastern Colorado, runs 13.1 miles below Rocky Mountain National Park.

As outlined in the Delaney Resolution and legislated in the Water Conservancy Act, compensatory storage to protect existing water rights and future development, if a proper survey was conducted, would be required for projects like the Colorado-Big Thompson (C-BT) by all water conservancy districts. With the C-BT, the West Slope gained Green Mountain Reservoir. Built between 1938 and 1943 on the Blue River southeast of Kremmling, with a capacity of 154,500 acre-feet, Green Mountain was the first portion of the C-BT constructed. The Green Mountain Dam built on the Blue River was Reclamation’s tallest earth-androck-fill dam at the time.

Despite this surge of activity taking place across the state to address West Slope concerns while meeting East Slope demands, Denver Water had no intention of providing compensatory storage and was not legally required to do so. Denver had just completed its Moffat Project in 1936, and in 1940 the Denver Department of Public Works completed the Williams Fork Diversion System, which brings water from the Williams Fork’s Steelman Creek and Bobtail Creek through the 2.9-mile-long Gumlick Tunnel, originally called the Jones Pass Tunnel, into Clear Creek. Denver Water purchased the entire system in 1955, and by 1958 added an additional component: the Vasquez Tunnel. The Vasquez Tunnel moves Williams Fork water, previously transported to Clear Creek, back under the Continental Divide into Vasquez Creek, a tributary of the Fraser River. There, Williams Fork water and Fraser water meet and enter the Moffat Tunnel. Denver Water maintained its legal position, not ceding to provide compensatory storage for either project, which led to a divisive relationship with the West Slope. Although that relationship has since evolved thanks to many conversations, long-negotiated processes, and cooperative management of West Slope resources, for some, transbasin diversions still conjure a visceral, negative reaction because of this long-standing idea of water being “stolen” by the East Slope, largely due to the Denver Water Board’s then-aggressive behavior.

John Edgar Chenoweth

Trinidad native John Edgar Chenoweth represented southeastern Colorado in the U.S. Congress from 1941 to 1949 and from 1951 to 1965. A conservative Republican opposed to federal spending projects, he was nevertheless the main congressional backer for the Fryingpan-Arkansas Project, which he believed would both benefit his district in the long term and be mostly repaid by fees from local water users. The Fry-Ark Project was enormously popular in Chenoweth’s district, and his support for it was largely responsible for his re-election in 1950. Although not a natural politician, Chenoweth spent his second stint on Capitol Hill gathering votes and learning how to maneuver around western Colorado’s powerful Congressman Wayne Aspinall, the House Democratic majority, and the sizable congressional delegation from southern California. Chenoweth went so far as to guarantee that the Fry-Ark Project would be the last federally funded transbasin diversion in Colorado, but even with this proviso, it took 11 years of political horse trading, rallying of popular support, and close-run elections before Congress and President John F. Kennedy finally approved the project in 1962.

to a more strategic state plan. Fryingpan-Arkansas bills made their way to Congress but were defeated in 1953 and 1955.

Two years later, in 1957, the Colorado River District’s board sent its representatives to Washington, D.C., where they collaborated with Californians to further 1955

diversions affect river recreation on both sides of the Continental Divide. On the Arkansas—the world-class whitewater river these rafters are paddling—water stored in reservoirs as part of the Fryingpan-Arkansas Project, along with announced releases, makes flows predictable and adds rafting days to the season. But those reservoirs also alter the natural seasonal flows of both the Arkansas and the Fryingpan rivers and reduce the occurrence of peak flows.

delay Colorado’s transbasin diversions. California had a strong incentive to slow Colorado’s water use: to extend its own use of that undeveloped water. After the meeting, the Colorado River District adopted a resolution suggesting a 20 percent limit on total Colorado River transbasin diversions going to the East Slope for 25 years. The River District amended the Fryingpan-Arkansas bill to include this provision, but the bill failed to get out of the House committee. In the end, these discussions of limited transbasin diversions led to the creation of the Colorado Water Congress, which formed in 1958, with the first meeting called by Governor Stephen McNichols and Attorney General Duke Dunbar between all of Colorado’s water users and government officials with the goal of alleviating tension between Front Range municipalities and West Slope water users.

Meanwhile, water users in the Arkansas Basin were frustrated—the Fryingpan-Arkansas Project legislation was not progressing. To reinvigorate and gather support for the project, they proposed the new Southeastern Colorado Water Conservancy District, formed in 1958. By 1959, the years of political lobbying and fundraising by Arkansas Basin stakeholders, as well as the River District’s persistence, were finally successful— parties on both sides of the Divide struck an agreement. Ruedi Reservoir on the Fryingpan River would provide 102,000 acre-feet

of compensatory and replacement water. The Southeastern district would repay the government $7.6 million, and the remainder of project costs would be covered locally. The project was signed into law by President John F. Kennedy in 1962, about 25 years after the CWCB initially proposed a transbasin diversion bringing water to the Arkansas.

In 1964, Fryingpan-Arkansas construction began with Ruedi Dam. The 5.4-mile long Charles H. Boustead Tunnel, which would be used to convey up to 69,200 acre-feet of water annually, was built between 1965 and 1971. Twin Lakes Reservoir was enlarged to provide additional storage for the project. Reclamation built Turquoise Reservoir, Pueblo Reservoir, and the Mt. Elbert Powerplant, the largest hydroelectric power plant in Colorado, on the Twin Lakes’ northern shore. Project water for irrigation and municipal uses was delivered in 1975; power was delivered from Mt. Elbert in 1981; and in 1990 a fish hatchery was dedicated at Pueblo Reservoir.

Today, around 50 percent of Fry-Ark Project deliveries go to agriculture in the Arkansas Basin, providing irrigation water for 265,000 acres. The project has also delivered water to municipalities since it began, first to the Colorado Springs area. One asyet unbuilt component of the project remains: a conduit delivering clean water to another 50,000 people in southeastern Colorado. When completed, it will bring water to users as far east as Lamar.

Changes in Colorado River Allocation and Storage

Other changes in Colorado's water world occurred during those decades of negotiation. In 1944, the United States and Mexico entered into a treaty, guaranteeing a portion of the Colorado River to Mexico and therefore reducing the amount available for use north of the border. That same year, Reclamation’s long-awaited Colorado Basin study was distributed to all Colorado River Basin states. The study, “The Colorado River: A Natural Menace Becomes a National Resource,” was a plan to develop the entire river. The plan proposed 88 projects for the Upper Basin, and though there was not enough water for all potential projects, it cautioned that the Upper Basin states had to “agree on sub-allocations of water to the individual states” before any construction would begin. After this draft premiered, the Upper Basin states convened a compact commission to apportion upper Colorado River water. In 1948, the Upper Basin states divided their collective Colorado River allotment through the Upper Colorado River Basin Compact. Under that compact, Colorado can pull 51.75 percent of the Upper Basin allocation after Arizona receives 50,000 acre-feet of water.

Shortly after the Upper Basin states divided their water, and as Colorado was negotiating the Fryingpan-Arkansas Project, the federal government in 1956 enacted the Colorado

River Storage Project Act. The Act’s primary purpose was to store and regulate flows on the Colorado River, allowing Upper Basin states to fully develop their entitlements and put that water to beneficial use while meeting 1922 Colorado River Compact and 1944 Mexico Treaty requirements.

By 1950, Colorado’s population was up to 1,325,000. The West Slope and the Colorado River District badly wanted Colorado River Storage Project units to store West Slope water, while Front Range water providers saw the Act as competition for the waters they might need for future development. Plans for specific storage projects were met with severe opposition. In the end, the Act authorized construction of the Flaming Gorge, Aspinall Unit, Navajo, and Glen Canyon dams in the Upper Basin. With development of Navajo in New Mexico came the San-Juan Chama Project, a transbasin diversion drawing water from Colorado’s San Juan River south and out of state into New Mexico’s Rio Grande Basin. In Colorado, the Aspinall Unit is comprised of Blue Mesa, Morrow Point and Crystal dams and reservoirs, located on the Gunnison River above the Black Canyon.

Although the Aspinall Unit is not a transbasin diversion, West Slope water stored in Aspinall Unit reservoirs helps maintain diversions out of the Colorado River Basin and meet water needs across the state by pooling and releasing water to meet Colorado River Compact requirements.

While the Fryingpan-Arkansas Project and Colorado River legislation were developing, so was Denver Water’s Blue River claim. Denver had claimed a right on the Blue in 1923, and the time was coming to develop that water. In 1942, Denver Water filed a request for adjudication of its Blue River rights with a 1914 priority date, the year the utility did a casual reconnaissance of the river. A 1914 decree would give Denver’s Blue River water priority over the 1922 Colorado Basin Compact and over all projects that came after, including the Colorado-Big Thompson Project. A 1914 decree for Denver’s upstream project would likely cut into the Green Mountain Reservoir replacement and mitigation water that was key to the Colorado-Big Thompson and would diminish a pool of water set aside for power generation and western Colorado’s future use. Very quickly, the West Slope and Bureau of Reclamation opposed Denver’s filing. After years in court and various water rights claims, Reclamation in 1949 filed a separate claim to affirm its right to water on the Blue over Denver’s claims. Reclamation estimated that its power production at Green Mountain and the associated revenue would be sliced in half if Denver received a 1914 decree.

In 1952, the court found Denver’s claims on the Blue legitimate but assigned the utility a priority date of 1946. Denver would

receive its Blue River water, but only after all senior rights filed before 1946, including all Colorado-Big Thompson water, received theirs.

Denver needed this water. The city was again pushing up against demand. During the 1940s, Denver’s population grew nearly 30 percent, from 322,000 to 416,000 residents. Growth in the suburbs was even more phenomenal. The population in Adams County increased nearly 79 percent; Arapahoe County, 62 percent; Boulder County, 29 percent; and Jefferson County, 83 percent. This was the biggest population boom since the 1880s gold rush. In the postwar years, Denver was issuing 5,000 new taps per year. By 1950, total water usage exceeded 100,000 acre-feet. Denver even drew a “blue line” defining service area boundaries in 1951, enclosing 114 square miles to ensure the utility could continue to meet growing demand. Metro area growth continued to explode in the 1950s. Denver lifted the blue line in 1960 because of developing feuds with sprawling suburbs that were demanding water. By erasing the blue line, Denver Water was accepting continued population and geographic expansion and would need to seek more water for the Metro area—an obvious threat to the West Slope. Denver could provide water for a limited service area, but for its expanding suburbs, the utility needed more.

ronmentalism grew larger and more effective than ever before. These federal laws, agencies and regulators gave new tools and voice to environmentalists and the general public and embodied the changing times.

Planning efforts and state law in Colorado, too, reflected shifting values associated with water. In 1970, Colorado’s population was 2,200,000. Senate Bill 97 passed in 1973, allowing the Colorado Water Conservation Board to hold instream flow water rights to protect the environment, leaving water in riv-

The 1970s also brought another attempt at state water planning in Colorado. Two state Department of Natural Resources employees, Chips Barry and Bill McDonald, put together a report that was later abandoned. The report discussed water-related values including fish and wildlife, recreation, wild and scenic rivers, and water banking. The study didn’t gain much traction, but the idea of incorporating some of these newer environmental values was emerging at the state level.

By the 1990s, that environmental ethic

deliver water from tributaries of the Eagle River to the 42,000 acre-foot Homestake Reservoir and then through the 5.5-milelong Homestake Tunnel for storage in Turquoise Reservoir near Leadville. The water is piped south to Twin Lakes Reservoir and then to the Otero Pump Station for delivery through the Homestake Pipeline. Half the water is conveyed to the South Platte River to reach Aurora’s reservoirs; the other half goes to Colorado Springs. But the growing cities needed more water and didn’t want to

rely on the supply of other cities like Denver to secure their futures.

In 1981 the two cities initiated the Homestake II project. Homestake II is where transbasin diversions and Colorado water supply projects in general enter this environmental era, an era where even municipalities who were exempt from providing compensatory storage under the 1937 Water Conservancy Act began cooperating out of necessity, lest they walk away without a project. But before the cooperation, there was disappointment and hostility.

When Aurora and Colorado Springs filed the Environmental Impact Statement for Homestake II, by then required by the 1970 National Environmental Policy Act, a number of environmental groups opposed the project. The Sierra Club, Audubon Society, Colorado Open Space Council, Wilderness Society and Colorado Mountain Club all fought Homestake II, along with local, grassroots environmental groups. By 1985, opposition also grew from Eagle County residents concerned about damage to the Holy Cross Wilderness Area, upon which some of their businesses depended. By 1987, public hearings took place, and in 1988, the Eagle County Board of Commissioners denied the Homestake II construction permit.

This was possible because of the “1041 powers” under the Colorado Land Use Act. The 1041 statute required Aurora and Colorado Springs to obtain a permit from Eagle County for their proposed diversion structures in Eagle County. When it denied the permit, Eagle County cited 20 reasons for doing so, including probable loss of wetland habitat in the Holy Cross Wilderness and potential environmental destruction. The cities took Eagle County to court, and the Court of Appeals ruled that “the cities’ entitlement to take water from the Eagle River Basin, while a valid property right, should not be understood to carry with it absolute rights to build and operate any particular water diversion project.”

Colorado Springs, Aurora and Eagle River entities spent the next decade in court, but after years of unresolved litigation, parties from both sides of the Divide came together to explore alternatives. Negotiations continued even when the U.S. Supreme Court ruled in Eagle County’s favor, ending the cities’ legal appeals. The Eagle River Memorandum of Understanding was signed on June 4, 1998, by Colorado Springs, Aurora, the Colorado River District, Climax Mine and numerous other parties in the Eagle River Basin.

In the end, the parties agreed that Aurora and Colorado Springs could at some point proceed with a transbasin diversion under certain conditions. The project would have to use different agreed-upon points of diversion outside the wilderness area. Any project negotiated in the future would need to be locally acceptable and meet strict environmen-

1977

The environmental era also hit Colorado’s Rio Grande Basin in the 1970s. There, transbasin diversions from the Gunnison River Basin, built in the early 1900s for irrigation needs, were purchased by the agency that would become Colorado Parks and Wildlife to use to improve habitat.

The Tabor Ditch runs just a half-mile and diverts an average of 700 acre-feet of water per year from the headwaters of the Gunnison to the Rio Grande Basin. Tabor’s water rights were changed in water court in 1979, so the water can now be used specifically for wildlife. Ten of the 11 Colorado Parks and Wildlife reservoirs in the Rio Grande Basin and its San Luis Valley benefit from Tabor’s diversions today.

The other Parks and Wildlife-owned ditches pulling water from outside the San Luis Valley still have irrigation-tied water rights that are used for the benefit of wildlife, largely on private lands. Through creative arrangements with private landowners, the water is used to irrigate cover crops or to fill wetlands to support migratory birds. The Weminuche Pass Ditch diverts an annual average of 1,325 acre-feet of water from a tributary of the San Juan into Weminuche Creek, and the Don La Font Ditches 1 and 2 divert from the Piedra River into the Rio Grande, together yielding just 190 acre-feet of water annually.

Only three other transbasin diversions deliver into the Rio Grande Basin, all carrying less water than the Weminuche and Tabor ditches and still used for agriculture or for replacing groundwater withdrawals.

A U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service employee works to recover endangered fish species as part of the Upper Colorado River Endangered Fish Recovery Program. Program partners cooperatively manage water to provide ample instream flows to benefit the fish.

After passage of the 1973 federal Endangered Species Act (ESA), four fish species were listed as endangered in Colorado by 1991: the humpback chub, bonytail, Colorado pikeminnow and razorback sucker. The fish struggled to adapt to many changes, including alterations to river hydrology, which challenged their survival. After the listing, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service sought to restore habitat and fish populations, recommending minimum streamflows for the fish in 1983. In 1988, the agency established the Upper Colorado River Endangered Fish Recovery Program, and with it, the San Juan River Basin Recovery Implementation Program.

With the recovery programs, water had a major new beneficial use on the Colorado River which would, and still does, impact water supply priorities and management decisions in Colorado. Flows that could be left in the river to support fish habitat were valuable, in part because without them the ESA could preclude diverters from continuing to withdraw water from the Colorado River Basin. Now there were efforts to purchase property and water rights and to re-operate existing reservoirs to provide flows for the endangered fish.

Recovery efforts focused on the “15-Mile Reach,” a stretch of critical habitat on the mainstem of the Colorado River near Grand Junction. There, many upstream transbasin diversions had produced a compounded impact on flows.

To bring water to the 15-Mile Reach, a 1993 agreement changed the operations of Ruedi Reservoir, the West Slope’s compensatory storage pool from the Fryingpan-Arkansas Project, where 21,650 acre-feet of discretionary water was identified for the program. The West Slope had been counting on that Ruedi water for future development, however. To reduce the effects on Ruedi’s participating entities, the East and West slopes entered into the “10,825 project” agreement. The agreement reduced the augmentation demand on Ruedi by half, while water users on both sides of the Divide each committed to provide 5,412.5 acre-feet of water for the 15-Mile Reach. The program continues today, and serves as a protection both for fish and for existing water diversions on both slopes.

Carter’s hit list; Interior Secretary Cecil Andrus recommends reconsideration of both projects for Indian water rights

1981 Spinney Mountain Reservoir and Homestake project are completed; Aurora and Colorado Springs initiate Homestake II project

tal standards. The MOU provides a framework for cooperative development of 30,000 acrefeet of water from the Eagle River—10,000 to Colorado Springs, 10,000 to Aurora, and 10,000 for in-basin Eagle River uses. To facilitate this, the parties also agreed to meet regularly over the next 20 years, working toward a project that would be acceptable to all parties.

Northern Colorado’s Windy Gap

At the outset of the environmental era, the Municipal Subdistrict of the Northern Colorado Water Conservancy District, created in 1970, also began the process of permitting a new transbasin diversion project, Windy Gap, with project negotiations beginning in 1971. The project was initiated to provide an additional 48,000 acre-feet annually to meet the growing demands of northern Colorado cities. By furnishing cities with water, the Subdistrict aimed to protect Colorado-Big Thompson water for its original purpose: irrigation. Initial Windy Gap project participants—Boulder, Longmont, Loveland, Estes Park, Fort Collins and Greeley—would divert additional Colorado River supplies to the East Slope using the existing Colorado-Big Thompson system.

Like Homestake II, Windy Gap was not a quick project—it was the new environmental era, after all. Longmont Mayor Ralph Price filed for water rights in 1967 on behalf of the six cities pursuing the project, but didn’t obtain the project’s decrees until 1980. Windy Gap’s Environmental Impact Statement was approved in 1981, and other permits and licenses took time and money.

Some of the same players, including the Colorado River District, were involved, but now the general public had a stronger

voice as well. The West Slope demanded compensatory storage for Windy Gap. The Subdistrict argued that because this new water went to existing Colorado-Big Thompson allottees, and because compensation had already been supplied to cover the quantity of water being requested, basin-of-origin protection had already been afforded through construction of Green Mountain Reservoir back in the 1940s. But the River District won, in the Colorado Supreme Court, a provision for compensatory storage for Windy Gap. Rather than continue with further litigation, an intense process of almost daily negotiations began in 1979, lasting for nearly five months.

Grand County asserted itself as a headwaters county already hit hard with ColoradoBig Thompson and Denver Water diversions. The Grand County Board of Commissioners had enacted land use regulations addressing transbasin diversions and thus the commissioners had to be satisfied. Beyond elected representatives, various businesses, governmental agencies and political subdivisions also had to be appeased. They were all invited to participate in negotiations and did. Parties included Grand County, Middle Park Water Conservancy District, the Town of Hot Sulphur Springs, and the Northwest Colorado Council of Governments. Days of negotiation allowed the Subdistrict to hear concerns and address them; in the end the Subdistrict negotiated a settlement agreement.

The agreement provided an additional 3,000 acre-feet of water for future development and $25,000 to Grand County for studies to address increasing salinity in the river due to lower water levels caused by diversions. The Town of Hot Sulphur Springs re-

ceived $420,000 to improve its water treatment and sewage systems, which it argued would be impacted by the project.

The Subdistrict also donated $550,000 for a habitat improvement project and biological investigation of Colorado River fisheries and studies to protect endangered fish on the Colorado—this gained them project approval by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. Habitat protections in and adjacent to the reservoir were also agreed upon to protect the Environmental Protection Agency’s wetlands concerns. And in negotiating with what was then the Colorado Division of Wildlife, now Colorado Parks and Wildlife, the Subdistrict provided for minimum flows on the Colorado River below Windy Gap Reservoir during times of diversion. The negotiations were so successful that Trout Unlimited issued a certificate of appreciation to the Subdistrict for preservation and maintenance of the fishery.

The issue of compensatory storage was negotiated, with the Subdistrict agreeing to build Azure Reservoir or an alternative for West Slope use. Azure Reservoir proved to be impractical, and the Subdistrict later proposed a pumped storage project to satisfy its mitigation obligation in place of Azure. Finally, in 1985 they negotiated the Azure-Windy Gap supplemental agreement in which the Subdistrict paid the River District $10.2 million to help fund the construction of a later storage project, Wolford Mountain Reservoir.

The Windy Gap permitting process, though arduous, was considered a great success. In a paper about the successful negotiations, Northern Water’s attorney John Sayre wrote, “I think that the Windy Gap Project and its Settlement Agreement shows that the basin of origin may be protected if reasonable

people will spend the time and make the effort to negotiate. The water supplies obtained, the interests protected and the environmental matters considered have, I believe, all been adequately accomplished and all parties seem to be satisfied over the results.” Despite the accolades, many believe Windy Gap had unanticipated consequences that invoked the need for additional mitigation years later.

Today, Windy Gap sends water through a series of lakes and reservoirs that capture and store water on the West Slope. Completed in 1985, Windy Gap Reservoir is a 445 acre-foot pooling reservoir which acts as a forebay for a pumping plant. Windy Gap permits allow the project to divert a maximum of 90,000 acrefeet in any given year, but over a 10-year average, Windy Gap diversions cannot exceed 65,000 acre-feet annually.

Failed Two Forks Project Leads to TransDivide Agreements

Mutual benefit and cooperation were practically unheard of, particularly for municipalities, just a few decades earlier. But these cooperative arrangements between Northern Water, the Colorado River District, Aurora, Colorado Springs and headwaters counties weren’t the only ones evolving. Following up on an initial 1905 claim on the Two Forks site by Denver Water’s predecessor, the Bureau of Reclamation put forward a proposal for a dam at the confluence of the north fork and the mainstem of the South Platte River, citing Denver and Aurora as primary beneficiaries in 1966. The vision was that the Two Forks project would act much like Gross Reservoir to store diversions from Colorado River tributaries. Denver was able to divert more water from the Blue River than it could store in Dillon Reservoir, hence the need for the proposed Two Forks Dam that would back up a new 1,100,000 acre-foot reservoir. If built, Two Forks would help supply water for Denver and 42 surrounding municipalities and would annually yield 98,000 acre-feet of water, with 25 percent of that going to Denver. The project was reworked in 1970 when the Rocky Mountain Center of the Environment voiced concern that Two Forks was lacking proper environmental review. In 1986, the Denver Water Board, by then the official proponent for the project, began the permitting process for Two Forks, but despite successfully securing a letter of intent from the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, to issue its permit, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency vetoed the project in 1990 under its Clean Water Act authority.

If nothing else signaled the end of an era for Denver, Two Forks did. Denver Water and its suburban partners had put $40 million and more than 10 years into developing the project, only to be shut down. “We got nothing out of it and that was using the old approach,

which had been very successful for Denver Water from its beginning,” says David Little, Denver Water’s director of planning. “Which is just pushing, persevere, work hard, keep pushing and you’ll get what you’re going after. In this case the environmental community had a better game plan.” By the 1980s, environmental interests were strong and basins of origin weren’t going to let Denver get away with simply taking the water. The days of filing for water rights and building a project without public input, Environmental Impact Statements, review, compliance, and mitigation, as Denver had done when it built its Moffat Project, were gone. At the same time, the mayor of Denver appointed an environmental representative to the Denver Water Board, and the Board hired a new director, Chips Barry, who brought a fresh management style and changed the face of Denver Water.

As Two Forks fell apart, Denver didn’t fight the veto, as the Denver Water Board would have done in the past, Little says, but instead dropped the whole thing to begin redefining itself and ease into more cooperative relationships. Cooperation wasn’t unheard of for Denver, which had begun forming better West Slope relationships in the late 1980s. Metro roundtable meetings led to meetings between the Denver Water Board and Colorado River District around 1984 and the brainstorming of a mutually beneficial reservoir. Before Two Forks was vetoed, Denver Water planned to temporarily lease water from that new West Slope reservoir for 25 years. Denver had hoped to secure enough water to serve its customers during the anticipated Two Forks construction, while the River District aimed to raise enough money leasing water that it could invest in additional Colorado River Storage Project projects. After the veto, that temporary lease lost its appeal to Denver, construction costs had increased, and the River District was struggling to fund the project. Denver extended an olive branch to the River District, offering to fund most of the reservoir in exchange for a lasting claim to 40 percent of the water. Using the funds from the Azure-Windy Gap agreement and the enhanced offer from Denver Water, the River District built Wolford Mountain Reservoir. This joint-use reservoir, allotting 60 percent of storage to the Colorado River District and 40 percent to Denver, was completed in 1996, signaling a major breakthrough from the tension that had existed between the entities for years.

Denver Water’s cooperative attitude continued. In 1992, Denver Water, Summit County, the Summit County Ski Areas, the Summit County towns, the Grand County towns and the Winter Park Ski Area entered into the Clinton Reservoir-Fraser River Water Agreement, or the Clinton Agreement, which implements a cooperative and more creative management

strategy on the upper Colorado River. The agreement aimed to provide additional water supplies for Summit and Grand counties— Denver agreed to operate its Dillon Reservoir and Roberts Tunnel water rights to allow Clinton Reservoir to store up to 3,650 acre-feet each year. That agreement began to solve problems in the headwaters counties and to mend relationships, but didn’t touch all of them.

Denver also completed a new integrated resource plan, published in 1996. Suddenly, water conservation was as much a priority as water project development, and water recycling was included in the utility’s strategy. Through that process, Denver wrote a resource statement with guidelines committing the utility to environmental stewardship, more cooperation with other metropolitan entities, the vow not to undertake any future structural projects on the West Slope without cooperatively developing those projects with West Slope entities, and more. Starting in the 1990s, Denver was no longer the bully, and water supply no longer meant building a new multi-million-dollar transbasin diversion.

From there, the Northwest Colorado Council of Governments initiated in 1998 a dialogue and study called UPCO, the Upper Colorado River Basin Study, through which Denver worked with Grand and Summit counties along with the Colorado River District, Northwest Colorado Council of Governments, Northern Water, and Colorado Springs to investigate water quantity and quality issues in headwaters counties. The process aimed to examine water issues, expand Denver’s hydrologic model for use in Grand and Summit counties, analyze impacts of current and future water supply and demand scenarios, and begin to solve water quality and quantity issues. The study indicated a need for additional water supplies in Grand and Summit counties for municipal demands and instream flows to support recreation and ecosystem health and to maintain low-flow levels for wastewater treatment plants. It found that some flow levels in the basin were inadequate to meet projected future growth and in many places were below minimum requirements for instream flows, fish and boating. It also predicted water supply shortages that would impact winter snowmaking at A-Basin and Keystone and showed a need for additional water in those headwaters counties—about 1,650 acre-feet a year on average. Although UPCO began with the intention of solving these issues, the cultural landscape had shifted and other cooperative processes began to look into solutions before UPCO could launch into its solutions phase.

This leads the story of transbasin diversions nearly to the present. Times, attitudes and values have changed. Most water agencies are better neighbors and environmental stewards, and the negotiations and cooperative agreements that began in the 1970s have grown into a way of life for water providers. Although some of these changes are attributable to culture and law, a large part of the cooperation the Colorado water community has undertaken more recently is borne of necessity. Now, population growth and climate are variables that all water suppliers must consider, and with more competition for water, using existing transbasin water supplies to extinction is not only an accepted option, but a necessary one.

Colorado’s population reached 5 million in 2008. New water is no longer easy to develop and appropriate, and hasn’t been for a long time. At the same time, researchers have made the public aware of climate change, which threatens to bring further unpredictability to Colorado. The CWCB warns that Colorado has warmed by 2.5 degrees Fahrenheit in the past 50 years and another 2.5 to 5.5 degrees of warming is predicted by 2050, with fluctuating drought and flood events, leaving water managers unsure of what to expect.

New transbasin diversions are few in this new era, but water providers have been looking to agricultural water, cooperative exchanges, conservation, recycling and other more creative tools to maximize water and enhance existing supply. The 2002 to 2003 severe drought stressed existing supplies, and it moved Northern Water’s Municipal Subdistrict and Denver to work on expansion or “firming” projects. Without these expansions, both entities draw less than the permissible amount from their transbasin diversions due to limited storage on the Front Range.

Windy Gap Firming and Environmental Mitigation

Northern Water’s Municipal Subdistrict, which now serves 15 entities, has no storage reservoir on the East Slope, and because the Subdistrict’s water rights are junior to most other upper Colorado River decrees, it can only divert water during above-average water years. To make the most of its transbasin diversion and water rights, the Subdistrict plans to construct the 90,000 acre-foot Chimney Hollow Reservoir adjacent to the Colorado-Big Thompson’s Carter Lake just west of Berthoud. In 2012, the Subdistrict

received a 1041 permit from the Grand County Board of Commissioners—a major step in moving the project along, and just one of many important permits—that only came after intense negotiation.

Although the Subdistrict’s initial Windy Gap Settlement Agreement with headwaters entities, signed in 1980, seemed like a great success, Grand County had suffered from years of diversions from the Colorado-Big Thompson, Windy Gap, and Denver Water diversions. “I don’t think we were very skilled at using our regulations to address the [original Windy Gap] project,” says Grand County’s manager, Lurline Curran. “We really didn’t look at it from a local perspective in the depth we could have. But we learned from that.”