4 minute read

Long-term progress

2.5.2

140

Advertisement

Long-term progress [21]

A new phase of economic growth began in the 1980s. Munich evolved into a high-tech metropolis within the framework of the Bavaria’s ambitious modernisation and investment policy.

At the same time, the chronic shortage of sites for new construction began to change into a surplus. Modernisation in many industries had left much commercial space vacant. The Deutsche Bundesbahn [German federal railroad] shifted extensive central rail facilities away from the city’s core and toward its outskirts. Additional space was also freed when military bases became unnecessary and could be closed in the wake of the collapse of the socialist power bloc.

A wave of large projects began with the goal of putting the vacated sites to good use. The strength of this movement prompted some commentators to describe it as a “new Gründerzeit.

Munich’s new airport provided new impetus for economic development and paved the way for Munich to become an indeed “global city.

The new airport inaugurated a change in Munich’s settlement development. Some 550 hectares became available at the site of the old airport. These plots also offered new opportunities for the tight inner-city real-estate market. Munich’s trade fair was able to move out of the crowded confines of the inner city and into more spacious surroundings formerly occupied by the old airport in Riem. This was the city’s second-largest investment project, rivalled in size only by the Olympic campus. A new neighbourhood with housing for 16,000 residents and jobs for 13,000 people was built south of the trade-fair campus. A generously proportioned green zone that stretches far into the city was also built.

141

142 The city developed a new neighbourhood around Bavaria Park near the old trade-fair campus. Conceived under the motto “compact-urban-green,” it became an exemplary project for high-quality inner-city development.

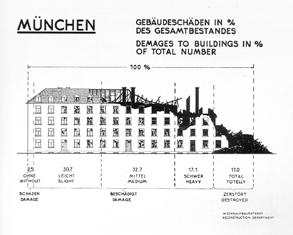

Although the reasons for Munich’s housing shortage have changed over the course of time, housing still remains scarce today. At first, flats were scarce because the city had been destroyed. Later, the shortage was due to the fact that increasingly large numbers of people wanted to settle in Munich. The population levelled off in 1972, but people tended to occupy more space per capita in ensuing decades. The average residential area per person increased from 15 m2 to 38 m2 between 1950 and the present day.

This was due to higher living standards and to an increase in the number of small households, for which there weren’t (and aren’t) enough small flats.

143

City in balance

144 More than half of all Munichers (54%) currently live alone; 30% live together with only one other person. These statistics have extensive consequences on urban planning. New dwellings and new settlements will still need to be built, even if the population remains constant or decreases. The infrastructure will likewise require continual expansion, even if the number of people to be supplied remains unchanged. The consequences of this development are a wide-ranging change in the character of urban life, increased paving of the land, and rising costs for heating, lighting, and transportation.

Since 1989, almost 165,000 new homes have been built in Munich. In future, the city aims to develop a further 8,500 new homes per year. The Urban Planning section continues a long-standing tradition spanning from the first city expansion in 1800 to the first ur-

ban architecture competition of 1892, Theodor Fischer’s guidelines and rules for the city. However, a growing population not only requires more homes, but also needs additional infrastructure and open spaces. The aim is to maintain the so-called “Munich mix” into the future – which is to say, to provide a diverse and wide-ranging offer of housing for all income groups.

The long-term settlement development is based on three strategies for new residential areas : Densification, restructuring and development on the urban fringes. Those are to be connected to the “Freiraum München 2030” study about the open spaces in Munich, dividing the concept as well into three topics – “open space & deceleration”, “open space & densification” and “open space & transformation.”

The boom of construction and investment has made an imprint on the Munich city centre. But how can Munich protect the qua-

145

146 lity of its historic “Altstadt” district despite its standing as a modern metropolis and a location for business? New guidelines propose answers to these issues.

Location to build housing is in short supply as said. It is crucial that potential sites will continue to develop. That might happen when businesses move to the outskirts leaving their production premises, such as at the Paulaner brewery or in the Werksviertel. Or, it involves the city’s edges, such as in Freiham or in Munich’s north-east, which are holding the last persisting vast fields of undeveloped land.

Redevelopments have always been a critical motor for urban development. Following the end of the Cold War and the reforms to the German Armed Forces, numerous military barracks were vacated over time, such as

147

Urban development and strategic projects

148 the Funkkaserne and the Prinz- Eugen-Kaserne, and it is not to forget the considerable amount of land reclaimed from the rail system, such as on Paul-Gerhardt- Allee. Many new residential areas have since the process began. Transforming a used site into a residential area depends on the ownership circumstances, site’s location, size, context and history.

Long-term Devs. 149