2 minute read

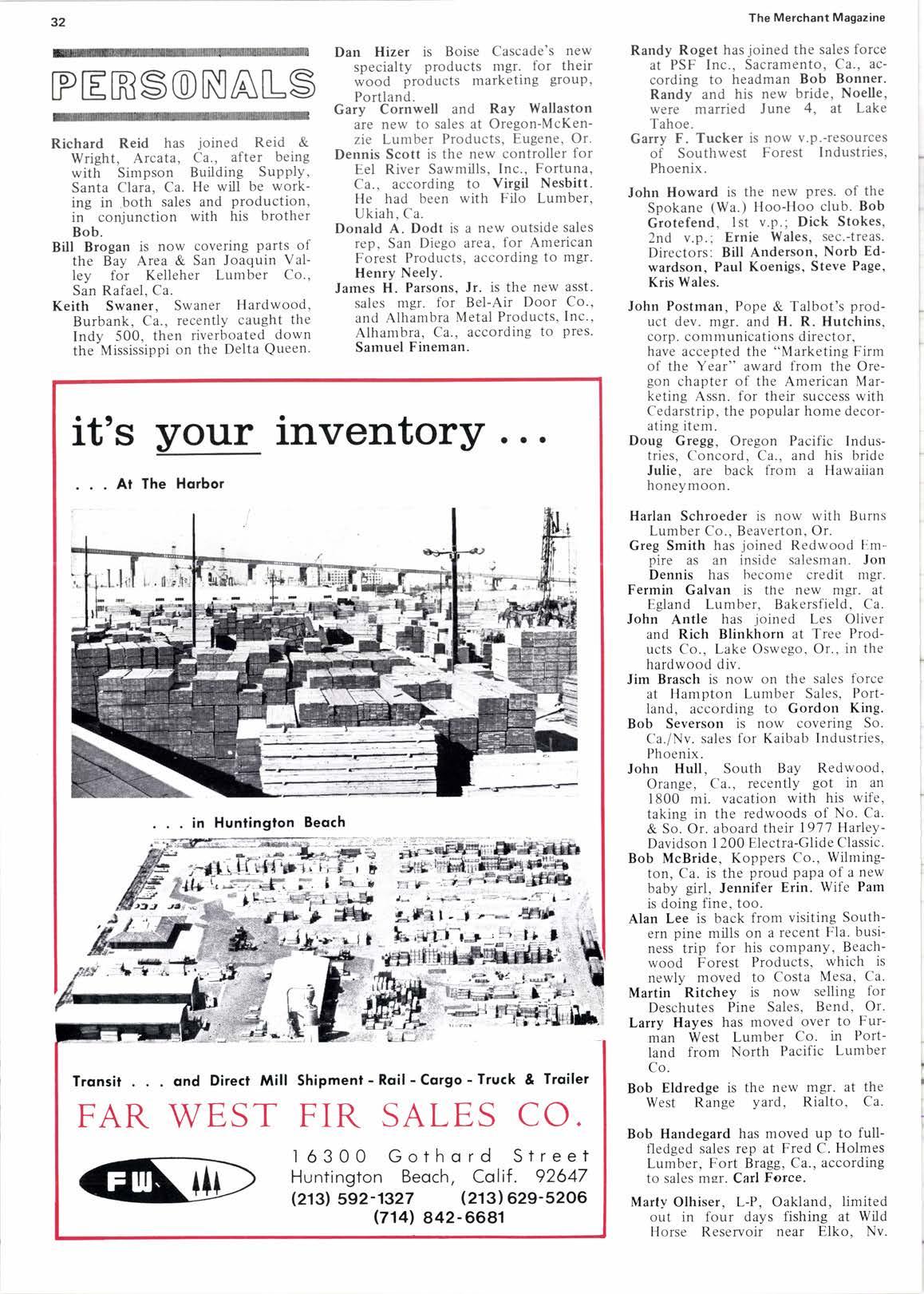

oast cargo lumber shipments

color shadings that only the sea can glve to those tenacious craft that survive her furies to presevere in their task.

This past year has seen the West coast cargo market increase dramatically as a number of conditions occurred to alter the usual patterns of commerce.

As Northern Canadian spruce sales increased in Eastern markets, and other Canadian export markets <ieclined, weather in Canada and the Pacific Northwest was mild enoush to allow a highly productive logging season. Weather in Southern California was "builder's weather" and demand was excellent and prices were above other markets. The Eastern part of the U.S. this past winter suffered under the worst weather on record or within ntentory, slowing or halting building and other lumberconsuming activity in the big Eastern markets.

The result was that instead of being shipped East, a larger than normal quota of lumber was shipped to the huge Southern California market. (For two related stories, see The Merchant, Sept. 1976, p. 22 and Feb. 1977, p.26).

It was, and is, an almost classical exercise in economics. The strons demand in Southern California for lumber caused prices to rise, which with the above circumstances resulted in an increased supply of lumber from the North. Earlier this year cargo shipments reached a rate of approximately 60 million board feet of lumber entering that market every month. As supply rose, inevitably, the prices first softened, then declined and fell. At this writing, the consensus is that they have bottomed and are rising slightly. But as most anyone who has earned his spurs in the business will tell you, forecasting the price of lumber is iffy at best.

The Canadian shippers of lumber, especially, have backed off the massive input of lumber seen earlier this year, as traditional Eastern markets revived. Some observers feel they do not see the Southern California market as a major market for them on a long term basis, but rather that they view it as another market.

In the past, cargo shipment of lunrber had large cost advantages over long distance rail and truck shipment. But recent increases in cargo costs and the implernentation of incentive rates by tlte railroads have elintinated much of the water shipper's advantage.

In the 1920s, between 80%-90% of the lunrber entering Southern California was by cargo. But the rise in influence of the maritime unions after the war dramatically escalated cargo costs, causing a loss of business to other forms of transportation, nrainly rail. Today, as then, cargo's advantage was that large bulk shipments of a heavy commodity could be made long distances with a rninimum of handling costs.

The price the wholesaler sells the lumber for that he buys at dockside is arrived at by a number of methods. Some include a commission percentage, but most is bought at a firm price.

Shipping times, barring the unforeseen, from British Columbia, Canada, to Southern California run 6-7 davs: from the Oregon Coast 5-7 days via ocean going barge. Lumber ships make the passage in 4-5 davs.

Predominately a Douglas fir market (something approaching 75%) it normally totals about two billion board feet per year, according to reliable estimates. A breakdown shows that Canadian lumber now is generally 50% hemlock and 5Wo Douglas fir, while lumber from the Oregon coast is 9Wo Douglas fir. A small amount of cedar is also shipped in this way.

The Ports of San Francisco and Oakland get only an occasional cargo shipment of lumber, as their proximity to Northern California markets allows truck and trailer shipment to do the job for less.

The days when lumber companies t-rwned and operated their own lumber carrying ships are long gone. Today, wholesalers and ntanufacturers charter ships, or space on ships, or work on regular contracts with well-established shippers such as Sause Brothers of Coos Bay, Or.

While the cargo business in recent years has seen sizeable shifts in business, there is little doubt that it will remain an important factor in the largest lumber market in the world.