11 minute read

ON AN INDUSTRY'S New, widetrack thinking vital if the lumber industry hopes to cope with its supply and demand problems

,THE United States has reached a sudden I turning point in theavailabilityofforest resources to meet national needs, as re' cent price fluctuations t*ply de^mo-nstrate. The ilramatic development of the nationos timber-availability problem is forcing into public consciousness a new view of the lorest resource in terms of shelter needs.

The goal of the 1968 Housing Act was "a decent home and suitable living envir' onment for every American familY'"

In quantitative terms, this means the construction o{ 26 million new living units in 10 vears" 6 million of them for low'and middle-income families.

For 1969, the goal was l'83 million homes. Stepping up production gradually in succeeding years, the homebuilding in' dustry would have had a fighting chance to meet the nation's l0-year requirements.

But economisx predicted only 1.6 mil' lion would actually be built this year.

Now. with the 1969 building season well underway, the National Association of Home Builders has predicted its members will fall 200,000 units short of the 1969 need. And that most of the shortage will be in low-and middle'income housing.

WHAT HAPPENED?

Mortgage prices have gone up. Land is more expensive. Labor costs have risen. And skilled labor is in short supply.

Yet even i{ all of housing's other prob' lems were solved, and even if the short' term problems affecting lumber and ply' wood supplies were solved, it still would be difficult, if not impossible, to meet the goals of the 1968 Housing Act.

Lumber manufacturers simply cannot obtain enough of the right kind of raw materialtimber suitable for conversion to lumber and plywood.

The timber is there. On federal land dedicated to growing it. It could be harvested without compromising forestry programs that promise abundant supplies of timber in perpetuity from the same land.

No law prevents putting that timber on the market. The agencies involved aren't conspiring against the nation.

IT'S MORE COIAPLICATED

A series of recent events have all had their efiect in bringing the crisis to a head in 1969.

The money shortage that hit home' building three years ago hit lumber and plywood producers, too. Their biggest market all but dried up.

With plants geared for a much higher demand, products were suddenly in oversupply. Prices fell. Only the most efficient plants could compete, so some producers shut down. A significant number were bankrupted. Skilled workers from these mills dri{ted away, to other jobs.

During the hot, dry summer oL 1967, extreme fire danger kept western loggers out of the woods. The following summer heavy rains in the same areas made forest roads nearly impassable. Then came the winter of 1968-69, with record cold and snow, virtually closing the woods.

It was in this atmosphere that homebuilding began its late-1968 rebound, generating today's enormous demand for lumber and plywood.

Douglas Fir lumber prices went up 29 percent in 1968, over a l2-month period.

The price paid for Douglas Fir timber -the harvested tree-in the most important growing region rose 118 percent.

Obviously, the demand for logs was greater than the'demand for finished ma' terial for the whole period. The reason was the buying pressure from Japan, with 2.2 billion board feet of logs shipped to that country iluring the year.

Limitations have since been put on export of logs {rom federal lands' But, even if they had existed in 1968, they wouldn't have completely solved the problems despite a year of comparatively light demand for lumber and plywood.

One independent forest economist has estimated that the economy could have absorbed an additional 2.4 billion board {eet of timber.

That volume of logs is equivalent to almost 10 percent of all the softwood lumber produced last yearor more than a third of all the softwood plywood manufactured in the U.S.

Other estimates indicate that at least 3 billion bd. ft. of timber could have been put on the market immediately by federal agencies to meet this shortage.

Betier Foresiry Needed

According to its own figures, the United States Forest Service has 54 percent of the national inventory of softwood timber -raw material for lumber and plywood. Industry owns 17 percent.

But only 28 percent of the total harvest comes from Forest Service land, and 36 percent from industry lands.

Industry's lands contribute 25 percent of the total growth; Forest Service lands only 20 percent.

Superficially, it appears that industry is 4t7, times more efficient at growing timber than the Forest Service, but that industry is depleting its share of the resource.

Neither conclusion is correct.

The theory of good forestry is the same as for good farming.

Trees grow little, if at all, after they reach maturity. Over-ripe stands begin to decay, like overripe tomatoes.

Mature timber must be harvested and newo vigorous stock planted to achieve rnaximum growth rate. Thinning, pest contiol and fenilization are all needed to get the most from forest land.

Industry practices this kind of intensive forestry. The Forest Service does not. Industry reinvests a portion of the income from its forest lands in making them more productive. The Forest Service is prevented frorn doing this.

Federal timber is sold like surplus gov. ernment property, to the highest bidder. The income from these sales goes into the general receipts.

Instead of being able to reinvest even a portion of its earnings for timber management, the Forest Service is obliged, like non-revenue producing agencies, to stand in line for Congressional appropriations to conduct its business.

As a result, managers of government timber must practice the most conservative forestry. And tley are so short of personnel and funds they cannot even ofler all the mature timber available now.

Poiiticai Problems

There are other problems, some of them short-term in nature, that have caused today's crisis.

But basic to all of them is the government policy that prevents efrcient utiliza. tion of a great and renewable resource.

Story dl o Glonce

Forces long simmering finally pop to suddenly present industry with problems that won't be solved either cheaply or quickly . problems appear surmountable, tho, if all involved get off their fat attitude.

The Congress has commenced what promises to be a long series of hearings to seek solutions. Officials of government agencies are explaining the - difrculties they face. Representatives of the President are studying data supplied by indus. try experts and their counterparts in government.

The forest products industry, in cooperation with the federal government, state forestry experts and the home building industry, is helping to ilevelop proposed solutions.

A complete answer, the industry believes, lies in the following areas:

(1) Revision of federal policies to take advanta$e of every modern advance in forestry and perpetual yield.

(2) Adequate, dependable funding of federal forestry. This will keep raw ma. terial flowing and encourage investment in new productive capacity.

(3) Encouragement of better private forestry, especially among the 3 million owners of small tracts that contain 18 percent of the national timber inventory.

(4) A" export policy based on the na. tional need, not just on crisis.

(5) A compleie review of national landuse requirements. The last such review was conducted in 1952.

(6) Solutions to the recurring ,transportation problems that often prevent supplies of lumber and plywood from reaching the market.

(7) More research on forestry and forest products utilization. The federal government does not presently contribute to this research in proportion to its position as a timber-owner.

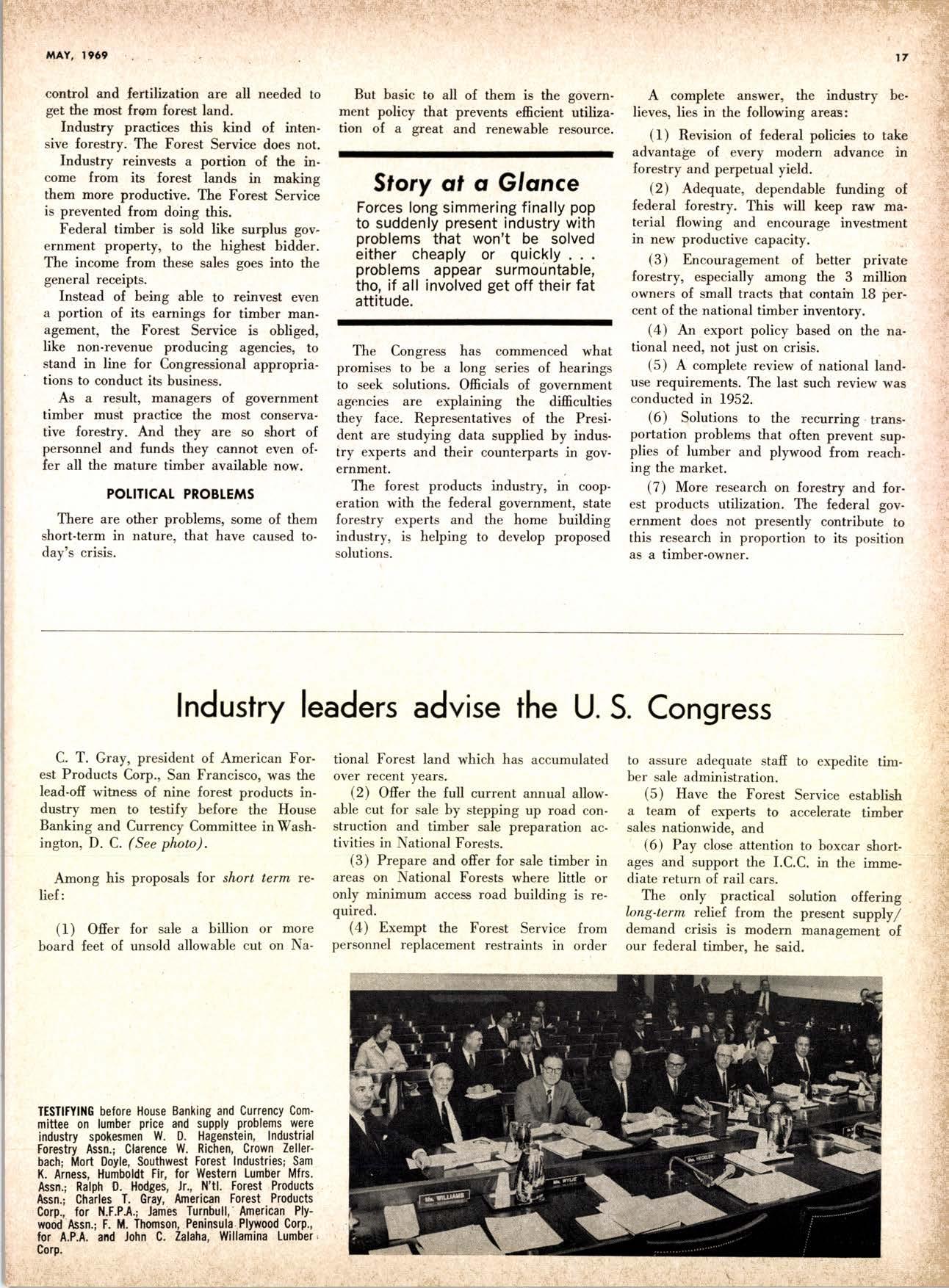

Industry leaders advise the U. S. Congress

C. T. Gray, president of American Forest Products Corp., San Francisco, was the lead-ofi witness of nine forest products indrst y men to testify before the House Banking and Currency Committee in Washington, D. C. (See photo).

Among his proposals Lor short term, relief:

(1) Ofier for sale a billion or more board feet of unsold allowable cut on Na- tional Forest land which has accumulated over recent years.

(2) Offer the full current annual allowable cut for sale by stepping up road construction and timber sale preparation activities in National Forests.

(3) Prepare and offer for sale timber in areas on National Forests where little or only minimum access road building is required.

(4) Exempt the Forest Service from personnel replacement restraints in order to assure adequate stafi to expedite timber sale administration-

(5) Have the Forest Service establish a team of experts to accelerate timber sales nationwide, and

(6) Pay close attention to boxcar shortages and support the I.C.C. in the immediate return of rail cars.

The only practical solution offering lang-term. relief lrom the present supply/ demand crisis is modern management of our federal timber, he said.

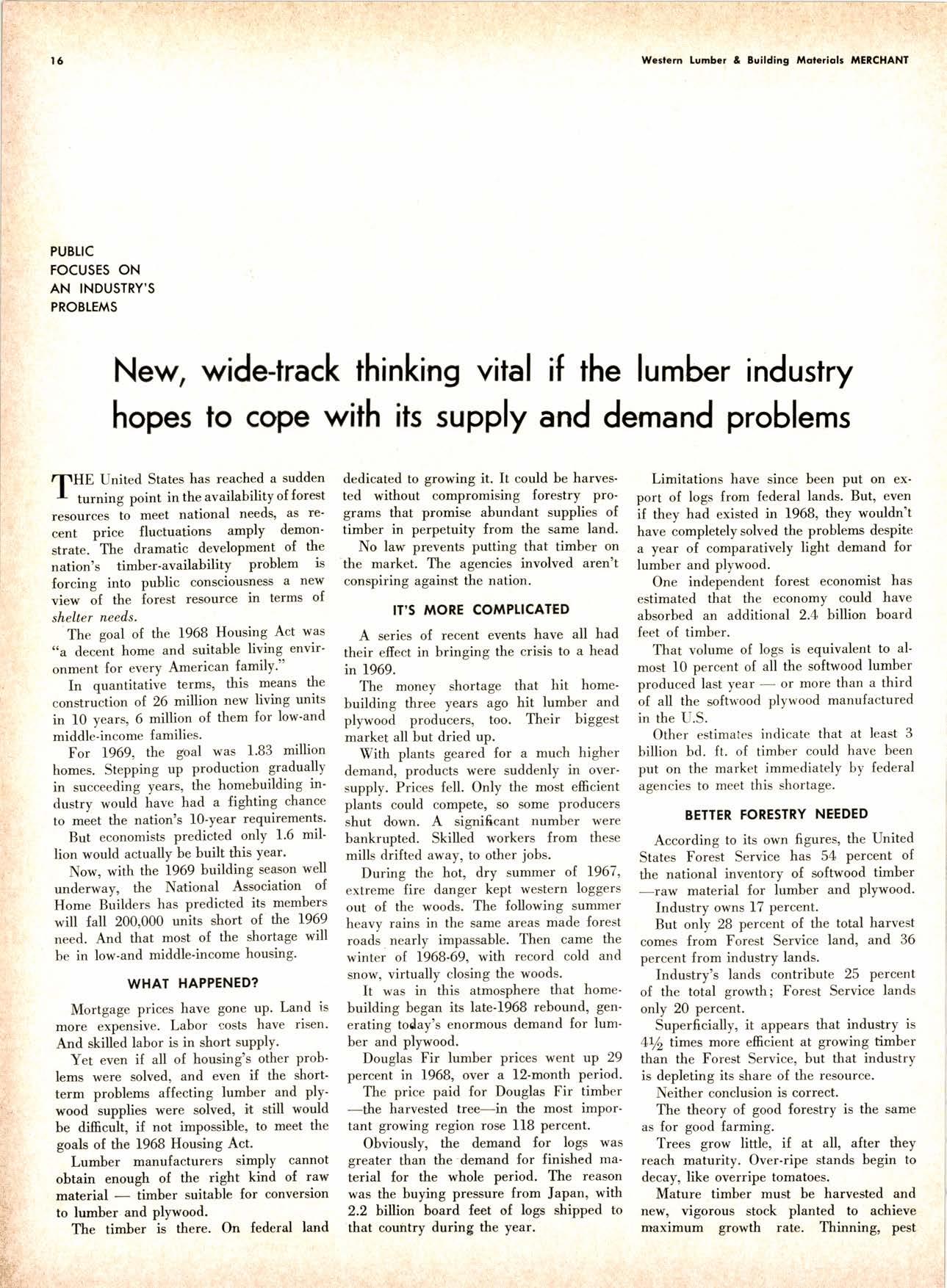

by Georse N. Kclm, tAorkctine C,on:"::{_,r, N. Kaht

Don'l Lend Buyers Money

The salesman who tries to carry on a sideline of lending money is asking for trouble.

In fact, this article could well be entitled 'oHow To Lose Customers." That's exactly what will happen to the salesman who be' comes a soft touch for his buyers. When a customer wants to borrow money from a salesman, the answer should be a polite but firm tono."

At first thought it might seem that the salesman is jeopardizing his relationship with the buyer by refusing' Quite the con' trary. The salesman who grants the loan is running a far greater risk of hurting his situation with the customer. I know of no buyer who has ever canceled an order or dismissed a salesman because the latter turned him down for a loan. But I know of many salesmen who have regretted lend' ing money to customers' One of these was Fred Jason.

A Bad Debt

Fred, an industrial scales salesrnan' was one of the highest paid men in his field. He also was one of the most liked.

One day a buyer, with whom Fred had dealt {or years, casually asked him for a $50 loan.

o'I'll have it for you the next time you call," the man assured Fred.

W'ithout hesitation, Fred took $50 from his wallet and gave it to the man.

Fred called at the account a month later and got a strange reception. He cooled his heels in the reception room for an hour after being told the buyer was oobusy." Previously, Fred had been whisked into the man's office upon arrival.

When the buyer finally did emerge he was brusque-almost curt. He gave Fred a routine order and dismissed him. Neither of the two mentioned the $50 loan.

On his next call Fred was treated even more coolly by the buyer' The latter reported through his secretary that he was 'otied up" and could not see Fred.

REPRIF{TS fOR SAIISMEN .. thir ls a condgmed -ver' rton. S.ct lccson is availablo irl a! crPlndod form' i4- I 4-Dsro broc,bute, dzc 8}1rU, pridcd iD,,z colors on wnfte d6r* paocr and ls 3-hole putrclod to nt ally sttaqalg -1' ifl -blidcf,. Esc.h etbicct in thir c8p,aadcd YE-rdqg i8 lqrv

|!d cooDlstoly dc'vclopod ln cqopfchcilivc {ct9u and ltr' dudc3 a s€U-GxaDlnation quiz fo3 salcsoco' Prtoct aro 8t

!ol!osg:

W.3Lm Lumbcr t Bullding Matrrlol: MEICHANI of several months to the buyer for a lead' ing department store. The latter had been deeply in debt before he tapped the sales' man as the result of gambling los6€s. He studiously avoided the salesman, going so far as to lie through his receptionist that he was out of town.

By this time Fred began to suspect that something was wrong. He insisted on seeing the customer, however, and was finally admitted.

The salesman asked the buyer for an explanation of his behavior, but the man only mumbled a thin excuse. When Fred pressed him further the' buyer flew into a rage.

"Look," Fred said, ooif it's the $50, I can wait."

This made the buyer even angrier. He denied the money had anphing to do with it. Whereupon, he quickly wrote out a check for $50 and threw it over to Fred.

Well, Fred got his money but he lost a customer. The buyer refused to see him again and the salesman's company had to assign a new man to that firm.

The Guilty Buyer

You must understand the motivation of the debtor. When a buyer borrows money from a salesman their relative positions change. Before, the buyer had considered himself in a superior position to the salesman. He was the one to whom the salesman had to come. He (the buyer) could dispense favors. The salesman depended on him for his bread and butter.

After the buyer has hit the salesman for a loan the relationship alters. Now the buyer feels himself in an inferior position. He is oblieated to the salesman and this fact changes his feeling toward him.

This feeling is heightened if the buyer can't pay back the loan when he promised. He may seek to avoid his creditor. When he is {orced to meet him" he will be cool, almost hostile.

Lending Ruled Out

A midwestern work clothing company has issued a standing order against the practice oI salesmen loaning money to buyers. It has instructed its salesmen that they risk losing their jobs by making such loans,

The rule was imposed after one of the firm's top salesnren lent $450 over a period

The salesman eventually lost the account. Fortunately, it was only temporary. The buyer's employer found out about his habits and fired him.

DON'T BORROW, EITHER

Some salesmen might ask me:

'oHow am I going to refuse a loan to a buyer I've known for 20 years and accounts for a third of my volume?"

Admittedly, this puts the salesman in a tough position, but not in an impossible one. There is absolutely nothing wrong with telling the man that it is your policy not to lend money to customerc. You might even explain your reasons. If he is at all reasonable he will understand and even admire you for your stand.

I know salesmen in the $50,000 income bracket who have a firm policy of not lending money to buyers. Obviously, their principles have not stood in the way of their success.

The Art Of Saying No

A business relationship should remain just that. The buyer is not your brother or father-in-law. He is not there to bail you out of your financial troubles' You will lose his respect by putting him on the spot with a request for a loan. You will be much better off going to your supervisor or someone in your organization. At least it's kept in the family so to speak.

When you ask a buyer for money, it's also bad publicity for your company' Your firm expects you to conduct your personal afiairs to reflect no discredit on it.

l. Do you manage your money so you don't run short? Yesfl No tr

2. Do you refrain from borrowing money from custdmers? Yes n No n

3. Are you concerned about your image with buyers? Yesn Non

4. Would you refuse a steady customer a loan? Yesn Non

5. Would you explain to him your reasons? Yesn Nof]

6. Are your relations with all your customers satis- factory? Yes n No []

7. Can you say that none of your customers owe you money? Yes ! No n

8. Do you believe a relationship with a buyer could be ruined by lending him money? Yes n No !

-iio-' p cootos (of acl gtttcto)-.s0 ccnts cach i to gtttclo)-.s0

10 to 49'coiicr (of och asdclo)-----J7t4 c.ctr cach

O asdc.to)-----J7t4

.'.:' :;-'-:^'E-^--- 22' Rooo At Tho Top Dos'n r- *6uro-On'Strfua lL PlttlsSThcshortcuc t5- V;u M&-GivJ-fuorc gZ. rtt -Stnslo ttG,E tO 99'coDfc! (o( cecl qtid!)=-------!g cmtl G8+

50 to t9r c(itc!

O (o( cach anicfd---------!Q G8c!

O ooll-copl6 (o'f oscrh rrdcf!)---J5 cqtt !4pA

5. ?ou Calt Fii Wtth- 13. Scllhs Aa ldor To GGt Voto Sslo -- out-Alrs|Itrittoo 14. Bwili cooDlB.Gr lo c oo[! cot li5 - ooll'coDl- (oil osch ardcl!) = '.ticqtg !4pt

Tb d! rcatc. mly bo PGofdcsod or tndtrmar artiqor ffi"ffii#.r* Gfl.-Ntl(rts ( _hl.Dt!dg!,.gn mv b dccd b|y Br|6bcr r.ldltat o(dcrt lo tb

E y b odcod bt nunbcr rddrc.t q4c!t !9 t!0

"Five ways to increased profits in 1969" includes powerful paneling promotional ideas that really lay it on the line lor you. Promotions are complete. From banners, ads and publicity to brochures, colorful vests and step-by-step instructions for scheduling and following through with your personnel. Choose from five exciting merchandising ihemes: "Treasure Chest of Values"l "Jubilee Sale"; "Ladies Day Paneling Sale"; exciting new "Time for Living" promotion or just plain "Truckload Sale."

![Ots[]ruAR[Es](https://assets.isu.pub/document-structure/230723114706-97e63af11a168e98adaa1f87acc1d925/v1/db2ef5d4896c1b2b058949bd592314fd.jpeg)