9 minute read

Gorlin-Goltz Syndrome with Familial Manifestation

Gorlin-Goltz Syndrome with Familial Manifestation

A Case Report with Emphasis on Early Diagnosis

Ravinder Singh; Deepak Gupta; Aashna Garg; Aanchal Gupta; Sushruth Nayak

ABSTRACT

Gorlin-Goltz syndrome is a hereditary autosomal dominant disorder. It has multiple clinical manifestations caused by mutation in the patched gene (PTCH), which is responsible for the growth and development of healthy tissue and for regulating the cell cycle. Early diagnosis of the condition and an extended duration of follow-up are essential to prevent complications, such as basal cell carcinomas and facial deformities, leading to a more favorable prognosis. This case was diagnosed with the presence of three major and two minor criteria, which confirmed the condition. We hereby report a case of a young male patient diagnosed by clinical, radiological and histopathological features, with further identification of his siblings presenting with the same condition. This case highlights the need to be aware of this rare condition in young individuals to facilitate regular monitoring and reduce the risk of complications.

Gorlin-Goltz syndrome (GGS) is a genetic, autosomal dominant disorder that has a sudden onset with a high penetrance and wide range of phenotypic expression.[1] The terms “basal cell nevus syndrome,” “nevoid basal cell carcinomas syndrome,” “multiple basal epitheliomas, jaw cysts and bifid rib syndrome” have all been used to describe this condition over time.[2]

It has been estimated that this condition affects 1 in 57,000 to 1 in 256,000 people, depending on the geographic location. Asians and African Americans account for barely 5% of cases, even though the condition affects people of all races with no gender predilection.[1]

In 1894, Jarisch and White provided the initial description of this condition. They emphasised the existence of several basocellular carcinomas. The diagnosis of the condition was reported by Gorlin and Goltz as having the traditional trio of numerous basal cell carcinomas, odontogenic keratocysts in the jaws and bifid ribs. Rayner et al. revised this diagnostic trio in 1977 and required that the OKCs had to present collectively, along with either palmar and plantar pits or calcification of the falx cerebri.[3] Numerous other characteristics have also been mentioned in the literature, including developmental deformities, like frontal bossing, hypertelorism, macrocephaly, cleft lip/palate, mandibular prognathism, skeletal deformities, urological, eye-related

abnormalities and tumors, like medulloblastoma and ovarian fibroma.[4]

Dental professionals should be aware of indications and symptoms that appear in the early and second decades of life. The presence of multiple odontogenic keratocysts is the main feature, in combination with the above-mentioned manifestations. Early detection is crucial because it can lessen the severity of consequences, including brain and skin cancers, and prevent maxillofacial abnormalities brought on by the jaw cysts. It further helps in genetic counselling of affected individuals and their families.[2]

In this case report, we present a young male patient with multiple odontogenic keratocysts, along with skeletal, facial, dermatological features in association with falx and tentorium cerebelli calcifications. The diagnosis of the condition was made in light of the clinical, radiological and histopathological findings.

Case Report

A 20-year-old male patient presented to the department of oral medicine and radiology complaining of pain in both the right and left tooth regions of the jaw for 10 days. Pain was severe, continuous and non-radiating in nature and was associated with bilateral swelling on the lower side of the face. Swelling was gradually progressive and was associated with difficulty in mouth opening for one year. Patient did not give any significant family history.

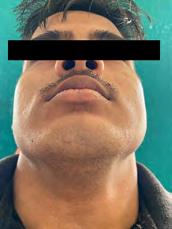

On general physical examination, there was evidence of Sprengel’s deformity (Figure 1a), along with palmarplantar keratosis and palmar pits.

On extraoral examination, there was evidence of mandibular prognathism frontal bossing and macrocephaly. Diffuse swelling was present on the lower side of the face bilaterally, extending superior-inferiorly from the ala-tragus line to the lower border of the mandible and anteriorposteriorly from an imaginary vertical line from the outer canthus of the eye to the angle of the mandible, measuring 3 cm x 4 cm approximately (Figure 1b). Swelling was roughly oval in shape and the same color as that of the surrounding skin. On palpation, the swelling was firm, with no localized raise in temperature and was mildly tender.

On intraoral examination, findings included mouth opening reduced to 25 mm (Figure 1c), the presence of an anterior deep bite with posterior crossbite, slight vestibular obliteration in the left mandibular buccal vestibule with respect to teeth #19 to #21, and microdontia with respect to teeth #7 and #28.

Orthopantomogram revealed evidence of bilateral osteolytic, unilocular radiolucencies surrounded by radio-opaque borders involving the ramus of mandible anterior-posteriorly and extending superior-inferiorly from 1 cm below the coronoid notch to the lower border of mandible with respect to impacted teeth #17 and #32, with the thinning of the outer cortex of the mandible measuring approximately 3.5 cm x 2 cm in dimension. There was evidence of other radiolucent lesions surrounded by radiopaque borders with respect to periapical areas of teeth #18, #15, #20 and #21 (Figure 2).

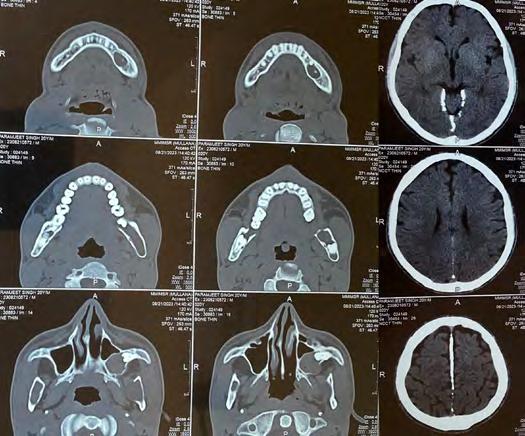

Non-contrast computed tomography of the face revealed evidence of multiple expansile cystic lesions involving the bilateral rami of the mandible, body of the mandible on the left side and left maxillary alveolus bulging into the left maxillary sinus associated with a deviated nasal septum and convexity toward the right side, and falx and tentorium cerebelli calcifications (Figure 3). A chest X-ray revealed rib deformities (Figure 4). Based on clinical and radiographic features, the patient was diagnosed with Gorlin-Goltz syndrome.

Surgical extraction and enucleation of the lesion were done in the region of tooth #15. Marsupialization of cystic lesions involving bilateral ramus, body of mandible and maxillary alveolus of left side was performed.

Tissue sample was then sent for histopathological examination. It revealed the presence of para-keratinized, corrugated, stratified squamous epithelium lining with thickness of four to six cell layers. The connective tissue wall surrounding the cystic lumen was filled with excessive keratin. The basal cell showed a hyperchromatic nucleus arranged in a palisading pattern. A few focal areas showed detachment of the epithelial lining from the connective tissue wall.

Although the patient did not provide any significant family history indicating familial predisposition, the patient’s siblings (two sisters and one brother) were called and examined, and they displayed similar skeletal, dental, cranial and developmental abnormalities. They were diagnosed clinically, radiographically and histopathologically with the same condition.

For the purpose of monitoring any potential skin lesions, the patient and his family members were referred to the dermatologist.

Discussion

Gorlin-Goltz syndrome (GGS) is a rare genetic disorder characterised by various developmental manifestations and propensity for neoplasms.[5]

The initial description of this condition was provided in 1894 by Jarisch and White. The existence of several basocellular carcinomas was their main concern. Then, in 1939, Straith described a case that involved cysts in addition to the carcinomas. A similar case was described by Gross in 1953 that included additional abnormalities in the ribs. Plantar and palmar pits were connected to this condition about the same time by Ward and Bettley. In 1960, Gorlin and Goltz proposed the trio of symptoms—keratocysts in the jaw, bifid ribs and numerous basocellular epitheliomas—that would be diagnostic for the identification of this disorder. Later, Rayner et al. added the presence of either palmar and plantar pits or calcification of the falx cerebri to this triad.[3]

A mutation in the PTCH1 gene, located on the long arm of chromosome 9q22.3, which codes for the patched receptor, is the root cause of the clinical presentation of this syndrome. This gene’s product suppresses tumor growth and plays a vital role in regulating the growth and development of healthy tissues. Loss of heterozygosity is exhibited by a number of tumors and hamartomas (BCC, OKCs, meningiomas, ovarian fibromas) but not by other lesions, such as palmar pits. Nearly 90% of hereditary basal cell carcinomas have been shown to have lost their PTCH1 locus heterozygosity.[6,7]

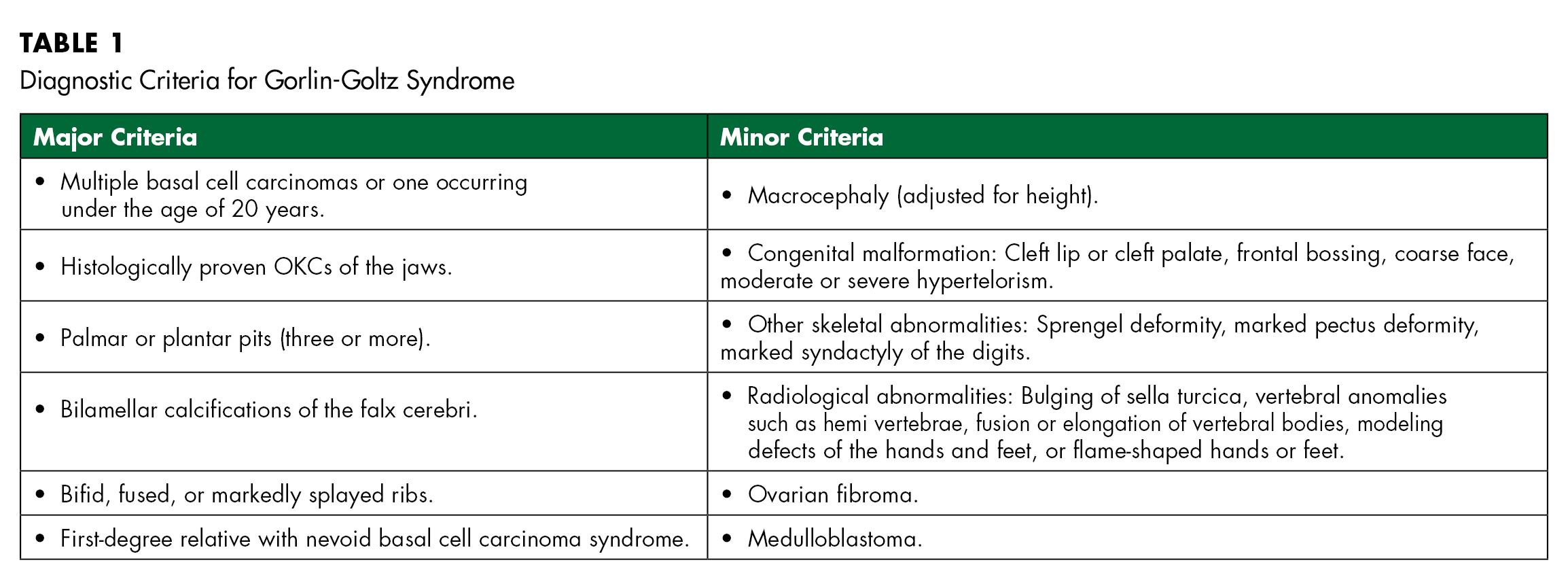

In order to diagnose the condition, Evans et al. originally defined major and minor criteria, which Kimonis et al. modified in 2004. To establish a diagnosis, two major and one minor or one major and four minor criteria must be present[8,9] (Table 1). In this case, three major and two minor criteria were present, which confirmed the diagnosis.

Odontogenic keratocysts characterised clinically by aggressive growth and a reoccurring tendency are among the most consistent and common features of this syndrome. A comprehensive assessment of the patient’s systemic conditions can lead to a GGS diagnosis. Every OKC case that has been diagnosed by histology should have a thorough assessment.[4] Management of odontogenic keratocysts include enucleation for smaller lesions, followed by mechanical curettage or chemical cauterisation with Carnoy’s solution or liquid nitrogen cryotherapy and marsupialization for large-sized cysts and bloc resection with or without preservation of the jaw.[10]

One of the manifestations of the condition that is most commonly seen, particularly in the head and neck region, is basal cell carcinomas. People should limit their exposure to unwanted ultraviolet rays because it is thought to be a risk for their formation and to impact their number. This explains why African Americans have fewer of these lesions, as melanin pigmentation acts as a protective factor. The skin surrounding the eyes, nose and ears is susceptible to BCCs. It is critical, therefore, that youngsters use eyeglasses with 100% UV protection[11] and that high sun protection (SPF 30+) be applied before heading outside. Reapply the sunscreen every two to three hours, and more frequently if swimming or perspiring.[12]

Early diagnosis is crucial in the case of GGS because it can lessen the likelihood of sequelae, including skin and brain malignant tumors, as well as the destruction and consequent oral maxillofacial abnormalities of the jaw cysts. In order to provide appropriate genetic advise, an early diagnosis is crucial. Furthermore, early diagnosis provides psychological support, aiding patients and their families in coping with the chronic nature of the syndrome and ultimately improves their quality of life.[13]