8 minute read

Subcutaneous Facial Emphysema and Pneumomediastinum Following a Class V Dental Restoration

Subcutaneous Facial Emphysema and Pneumomediastinum Following a Class V Dental Restoration

A Case Report

Jonathan Tran, D.D.S.; Brian M. Will, D.D.S., M.D.; Sidney B. Eisig, D.D.S.

ABSTRACT

Cervicofacial subcutaneous emphysema is an uncommon but potentially life-threatening complication of dental procedures. While classically associated with surgical extractions performed with dental high-speed handpieces instead of surgical rear-exhaust handpieces, it has been documented following other dental procedures, including restorative and endodontic treatments. As cervicofacial air emphysema spreads, it may reach the retropharyngeal space, which connects to the mediastinum, leading to pneumomediastinum and a risk for mediastinitis, which carries a high mortality rate. We present a case of cervicofacial subcutaneous emphysema leading to pneumomediastinum following a Class V restoration on tooth #28 to highlight the importance of recognizing this underdiagnosed complication.

Cervicofacial subcutaneous emphysema is a potential complication of dental procedures that results from the introduction and entrapment of air in the subcutaneous space. While described as rare, it is possible that the complication is underreported due to its often asymptomatic and self-limiting course. Nonetheless, it carries the potential to progress into life-threatening complications, including airway compromise, pneumomediastinum, pneumopericardium and mediastinitis. Diagnosis is often made based on history and physical exam, wherein crepitus on palpation can be considered pathognomonic.

In reporting this case, we hope to highlight subcutaneous emphysema to clinicians as a potential complication that can arise from simple restorative procedures and rapidly progress to pneumomediastinum. Therefore, it should be included as part of a differential diagnosis for patients who present with swelling following dental treatment.

Case Report

A 28-year-old female presented to the emergency department with right-sided facial swelling, crepitus upon palpation of the right cheek and neck, throat pain and mild odynophagia, which began three hours after seeing her general dentist for a Class V restoration on tooth #28, a short 15-minute procedure (Figure 1). The patient noticed difficulty swallowing immediately after the procedure, but her dentist attributed the sensation to the effects of anesthesia and sent her home. Her symptoms continued to worsen, at which point she presented to the emergency department for further evaluation.

The patient was otherwise healthy with no significant medical or surgical history, allergy to penicillin, no tobacco use, social alcohol consumption, no recreational drug use and taking only drospirenoneethinyl estradiol birth control. Initial review of systems was significant for right ear discomfort, which the patient likened to the feeling of water in her ear. Intraoral examination revealed localized gingival erythema near tooth #28, as well as pain and mild bleeding on palpation of the alveolar ridge adjacent to tooth #28. The buccal Class V composite restoration on tooth #28 was intact.

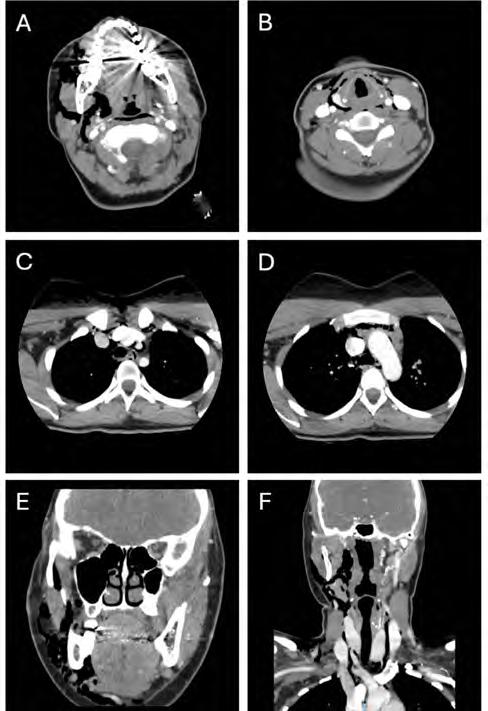

Laboratory findings upon presentation were significant for a white blood cell count of 16.29 x 109/L. Maxillofacial, neck and chest CTs with contrast were taken, revealing subcutaneous and deep soft-tissue emphysema extending from the right masticator space, through the superficial and deep fascial planes of the neck, into the retropharyngeal space and inferiorly into the mediastinum (Figure 2). The patient was admitted for observation and received intravenous clindamycin. An esophagram was ordered to rule out esophageal perforation.

White blood counts returned to normal one day after admission. Repeat maxillofacial and chest CTs with contrast two days after admission revealed improvement, with decreases in subcutaneous emphysema and tissue edema, and the patient was deemed ready for discharge with continued supportive management at home. The patient was prescribed oral clindamycin and advised to take over-thecounter analgesics as needed. The patient was seen for follow-up in the outpatient oral and maxillofacial surgery clinic two days after discharge; she continued to improve with no signs of worsening infection (Figure 1).

Discussion

The source of the air in a subcutaneous emphysema following dental treatment may be a dental handpiece, air syringe or air polisher and, thus, the complication has been documented following a wide range of procedures, including extractions, restorative treatments, cleanings and endodontic therapy.[1–5] Since this case involved a Class V restoration, the source of the air emphysema was likely from the dental high-speed handpiece used to excavate the caries and prepare the tooth or the air syringe used to dry the tooth. Class V restorations often require the use of retraction cord, and aggressive cord packing may have weakened the surrounding gingival attachment on tooth #28 and allowed air to dissect through the gingival sulcus and enter the adjacent soft-tissue spaces. When applicable, rubber dam placement can provide isolation that prevents air from dissecting into the soft-tissue spaces. Additionally, care should be taken to minimize blowing the air syringe towards the gingival sulcus to minimize the risk of this complication.

Air and infection must travel through a series of deep spaces of the head and neck to reach the mediastinum. Dissecting air that initially enters the submandibular space freely travels to the masticator space. From there, it can cross through the buccopharyngeal gap wherein the styloglossus passes between the superior and middle pharyngeal constrictors and reaches the lateral pharyngeal space. The lateral pharyngeal space communicates with the retropharyngeal space, which exists between the buccopharyngeal fascia and the alar fascia. The alar fascia separates the retropharyngeal space from the danger space and merges with the buccopharyngeal fascia at the level of C6-T4 inferiorly. As the alar fascia is thin, it may be difficult to visualize on cross-sectional imaging in healthy patients and, thus, the retropharyngeal and danger spaces may appear as a singular space. Air that reaches the danger space may enter the mediastinum, potentially leading to airway compromise, pneumomediastinum, pneumopericardium and mediastinitis.[5]

Subcutaneous emphysema and even pneumomediastinum are self-limiting but have a rare risk of developing into the life-threatening complication of mediastinitis from the spread of bacteria or debris carried by the dissecting air. Iatrogenic mediastinitis, as well as descending necrotizing mediastinitis from odontogenic infections, have been reported to have a mortality rate as high as 30% to 40%.[6-8] Management of subcutaneous emphysema following dental procedures with antibiotics is aimed at preventing the spread of oral flora through the deep spaces of the neck and mediastinum, which could lead to cellulitis, necrotizing fasciitis or mediastinitis.

Although well-documented in the literature, subcutaneous emphysema continues to go undiagnosed by dental providers, as seen in this case. Aside from subcutaneous emphysema, a differential diagnosis of a patient that presents with a swollen face and neck after dental treatment may include cellulitis, angioedema or hematoma. Cellulitis would present with systemic signs of infection, such as fever, malaise and lymphadenopathy. Angioedema swellings would be firmer and present with erythema and urticaria. Hematomas are associated with local anesthetic use and manifest rapidly with tissue discoloration due to the extravasation of blood.

Crepitus on palpation is a key physical exam finding that would suggest subcutaneous emphysema, and the presence of gas within the fascial spaces on CT imaging would provide confirmation.

Conclusion

We present a case of cervicofacial subcutaneous emphysema leading to pneumomediastinum in a healthy patient following dental treatment for a Class V restoration on tooth #28. While uncommon, this complication requires urgent management due to the risk for fatal sequelae, such as mediastinitis. Dental providers must be able to recognize the signs and symptoms of this complication to provide appropriate management for their patients.

Queries about this article can be sent to Dr. Tran at jt3284@cumc.columbia.edu.

References

1. Busuladzic A, Patry M, Fradet L, Turgeon V, Bussieres M. Cervicofacial and mediastinal emphysema following minor dental procedure: a case report and review of the literature. J Otolaryngol - Head Neck Surg 2020;49(1):61. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40463-020-00455-0.

2. Tegenbosch C, Wellekens S, Meysman M. A swollen face and neck after dental surgery: think of subcutaneous emphysema and pneumomediastinum. Respir Med Case Rep 2023;46:101926. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rmcr.2023.101926.

3. An GK, Zats B, Kunin M. Orbital, mediastinal, and cervicofacial subcutaneous emphysema after endodontic retreatment of a mandibular premolar: a case report. J Endod 2014;40(6):880–883. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joen.2013.09.042.

4. Alonso V, García-Caballero L, Couto I, Diniz M, Diz P, Limeres J. Subcutaneous emphysema related to air-powder tooth polishing: a report of three cases. Aust Dent J 2017;62(4):510–515. https://doi.org/10.1111/adj.12537.

5. Breznick DA, Saporito JL. Iatrogenic retropharyngeal emphysema with impending airway obstruction. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 1989;115(11):1367–1372. https://doi. org/10.1001/archotol.1989.01860350101024.

6. Dirol H, Keskin H. Risk factors for mediastinitis and mortality in pneumomediastinum. J Cardiovasc Thorac Res 2022;14(1):42–46. https://doi.org/10.34172/jcvtr.2022.09.

7. Roccia F, Pecorari GC, Oliaro A, et al. Ten years of descending necrotizing mediastinitis: management of 23 cases. J Oral Maxillofac Surg Off J Am Assoc Oral Maxillofac Surg 2007;65(9):1716–1724. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joms.2006.10.060.

8. Sakamoto H, Aoki T, Kise Y, Watanabe D, Sasaki J. Descending necrotizing mediastinitis due to odontogenic infections. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod 2000;89(4):412–419. https://doi.org/10.1016/s1079-2104(00)70121-1.

Jonathan Tran, D.D.S., is a graduate of Columbia University College of Medicine, New York, NY, and an oral & maxillofacial surgery resident at University of California Los Angeles, Los Angeles, CA.

Brian M. Will, D.D.S., M.D., is a graduate of the Oral & Maxillofacial Surgery Residency Program at New York Presbyterian Columbia University Irving Medical Center, New York, NY.

Sidney B. Eisig, D.D.S., FACS, is chairman of Hospital Dentistry and director of Oral & Maxillofacial Surgery at New York Presbyterian Columbia University Irving Medical Center, New York, NY.