FALL 2022 ISSUE 01

SPECIAL FEATURE SCARS

FALL 2022 ISSUE 01

SPECIAL FEATURE SCARS

All societies are burdened by their pasts. Misguided and self-interested decisions by previous leaders, structural inequalities that have been left un- or only half-addressed, or even a few strokes of bad luck can leave lasting scars. And like those on the human body, political scars are not only cosmetic—they are also reminders of past injuries and reveal our attempts to heal from them. Here on College Hill, for example, Brown has long grappled with its connections to the Atlantic slave trade. The university’s effort to better understand and teach students about these connections represents a process of healing. But the scar—and the legacy of oppression that Brown took part in—will never disappear. Political scars are not only part of a society’s identity, but they can also shape its future. In Russia and Ukraine, the scars left by financial crises and political turmoil after the fall of the Iron Curtain helped create the conditions that led to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. Scars, therefore, do not just reveal a past injury. They also inform how we respond to current issues. They can cause us to lapse into old, harmful habits or make shortsighted decisions, reproducing the injuries that created the scar in the first place. Or they can also do the opposite, reminding us of our past mistakes and spurring careful thought about the future.

The authors in this magazine’s special feature explore all of these dimensions of scars. In his article, Nealie Deol examines how the Partition of India and Pakistan in 1947 led to mass violence against the Sikh minority but also fostered a Sikh identity that defined Punjab as its homeland. The scar left by Partition helped galvanize Sikh political nationalism.

Our authors also discuss how scars can perpetuate cycles of self-interested and misguided political decision-making. Francisca Saldivar investigates how the scars left by 70 years of oneparty rule by the PRI in Mexico still shape politics today. Despite being elected on a reformist platform, President Andrés Manuel López Obrador has made alliances with PRI members to expand executive power through a new national security law. Ian Stettner examines how the botched raids in Somalia in 1993 left a scar on American foreign policy, pushing the country toward harmful isolationism. He argues that the scars of past blunders can cause foreign policy-makers to overcorrect for past mistakes. And lastly, some authors explain how we must learn from scars to prevent future harm. Elliott Smith contends that overturning the Insular Cases—a series of Supreme Court decisions that rule that the US Constitution does not apply to territories, and thus that residents there do not possess the same rights as people in the states—presents an opportunity to mend the scars left by racism and imperialism. Will Forys zooms in on Tangier, a small island in the Chesapeake Bay that is sinking as sea levels

rise. The environmental disaster facing Tangier, and the resulting cultural loss, will leave a scar. But it will also, quite viscerally, demonstrate the urgency of tackling rapid climate change.

We hope these articles will make you consider the varied ways in which scars can impact our political past, present, and future. How are societies to learn from their past scars, and who decides how they do this? And are there are times where it is more productive to just try to wipe the slate clean?

− Gabe and Matt

The Scars Issue Brown Political Review

EXECUTIVE BOARD

EDITORS IN CHIEF

Gabe Merkel

Matt Walsh

CHIEFS OF STAFF

Casey Chan

Sarah Roberts

CHIEF OPERATING OFFICERS

Daniel Halpert

Gidget Rosen

SENIOR MANAGING

MAGAZINE EDITOR

Nathan Swidler

MANAGING

WEB EDITORS

Chaelin Jung

Morgan McCordick

Mathilda Silbiger

CHIEF COPY EDITORS

Robert Daly

William Lake

INTERVIEWS DIRECTORS

Alex Fasseas

Miles Munkacy

DATA DIRECTORS

Zoey Katzive

Arthi Ranganathan

CREATIVE DIRECTORS

Christine Wang

Daniel Navratil

MULTIMEDIA DIRECTOR

Elijah Dahunsi

LEAD WEB DEVELOPER

Sarah Roberts

CONTENT BOARD

MANAGING

WEB EDITORS

Chaelin Jung

Morgan McCordick

Mathilda Silbiger

SE NIOR EDITORS

Natalia Ibarra

Sarah McGrath

Isabella Yepes

EDITORS

Ben Ackerman

William Forys

Jillian Lederman

Alex Lee

Matthew Lichtblau

Kara McAndrew

Francisca Saldivar

Isaac Slevin

Jack Tajmajer

ACTIVISM SECTION EDITORS

Sofia Barnett

Amanda Page

Gabby Smith

STAFF WRITERS

Ilektra Bampicha-Ninou

Omri Bergner-Phillips

Anna Brent-Levenstein

CREATIVE BOARD

CREATIVE DIRECTORS

Daniel Navratil

EDITORIAL BOARD

SENIOR MANAGING

MAGAZINE EDITOR

Nathan Swidler

MANAGING EDITORS

Alexandra Mork

Joseph Safer-Bakal

Ye Chan Song

ASSOCIATE EDITORS

Grace Chaikin

Harry Flores

Isabel Greider

Lauren Griffiths

Justen Joffe

Caroline Parente

David Pinto

Cole Powell

Bianca Rosen

Antara Singh-Ghai

Bryce Vist

Archer Zureich

STAFF WRITERS CONT.

McConnell Bristol

Morgan Dethlefsen

Neve Diaz-Carr

Henry Ding

Juliet Fang

Amina Fayaz

Michael Farrell-Rosen

Sophie Forstner

Isabella Garo

Oamiya Haque

Ashton Higgins

Katie Jain

Elsa Lehrer

William Loughridge

Bruna Melo

Christina Miles

Alexandra Mork

Kayla Morrison

Rohan Pankaj

Annika Reff

Andreas Rivera Young

Jodi Robinson

Bianca Rosen

Mira Rudensky

Zane Ruzicka

Ellie Silverman

Elliot Smith

Ian Stettner

Peter Swope

Maddock Thomas

Man Hei Christopher Wai

Jesse Ward

Ben Youngwood

Sofie Zeruto

Suzie Zhang

COPY EDIT BOARD INTERVIEWS BOARD

CHIEF COPY EDITOR

Robert Daly

William Lake

MANAGING COPY EDITORS

Andrew Berzolla

Isabel Greider

COPY EDITORS

Emily Colon

James Dallape

Khalil Desai

Mira Echambadi

Juri Kang

Connor Kraska

Caleb Lazar

Dorothea Omerovic

Jimena Rascon

Lilly Roth-Shapiro

Roza Spencer

Audrey Taylor

Sabina Topol

Hao Wen

Logan Wojcik

Ivy Zhuang

INTERVIEWS DIRECTORS

Alex Fasseas

Miles Munkacy

DEPUTY INTERVIEWS DIRECTORS

Mira Mehta

Samuel Trachtenberg

Alexandra Vitkin

INTERVIEWS ASSOCIATES

Ahad Bashir

Carson Bauer

Omri Bergner-Phillips

Allie Chandler

Léo Corzo-Clark

Elise Curtin

Elijah Dahunsi

Alexander Delaney

Mira Echambadi

Ava Eisendrath

John Fullerton

James Hardy

Alice Jo

John Kelley

Stella Kleinman

Sam Kolitch

Seungje (Felix) Lee

Alexandra Lehman

Alyssa Merritt

Lauren Muhs

Hai Ning Ng

Matteo Papadopoulos

Maya Rackoff

Anushka Srivastava

Emma Stroupe

Anik Willig

Hiram Valladares Castro-Lopez

Yuliya Velhan

Tucker Wilke

Christine Wang

DESIGN DIRECTORS

Erin Isla Roman

Hope Wisor

GRAPHIC DESIGNERS

Muhaddisa Ali

Patrick Farrell

Youjin (Amy) Lim

Kara Park

Alina Spatz

Erica Yun

Airu (Ivy) Zhang

Tina Zhou

ART DIRECTORS

Rosie Dinsmore

Jacob Gong

Lucia Li

Anahis Luna

Lana Wang

Kelly Zhou

DATA BOARD

DATA DIRECTOR

Zoey Katzive

Arthi Ranganathan

DATA DESIGN DIRECTOR

Lucia Li

DATA ASSOCIATES

Veer Arora

Carson Bauer

Allie Chandler

Elsa Choi-Hausman

Khalil Desai

Ryan Doherty

Raima Islam

Asher Labovich

Nicole Lugo

Javier Niño-Sears

Colby Porter

Logan Rabe

Francisca Saldivar

Jake Siden

Giang Thai

Harry Yang

Yifan (Titi) Zhang

DATA DESIGNERS

Icy Liang

Hannah Jeong

Mahnoor Rafi

MULTIMEDIA BOARD

MULTIMEDIA DIRECTOR

Elijah Dahunsi

MULTIMEDIA ASSOCIATES

Ilektra Bampicha-Ninou

Garv Gaur

Ashton Higgins

Julia Kostin

Haotian Luo

Daniel Ma

Ruairi Mullin

Taha Siddiqui

Michael Seoane

Jonathan Zhang

COVER ARTIST

Nicholas Edwards

ILLUSTRATORS

Jason Aragon

Ashley Castaneda

Naya Lee Chang

Jocelyn Chu

Kyla Dang

Thomas Dimayuga

Nicholas Edwards

Pauline Han

Maria Hahne

Grace Li

Elizabeth Long

Wenqing (Ash) Ma

Temilola Matanmi

Rosalia Mejia

Kennice Pan

Ji Hu Park

Shreya Patel

Kira Saks

Evelyn Tan

Ayca Tuzer

Madison Tom

Rachel Zhu

BUSINESS BOARD

BUSINESS DIRECTOR

Daniel Halpert

Gidget Rosen

ASSOCIATE BUSINESS DIRECTORS

Charlie Key

Stella Kleinman

Meghan Murphy

BUSINESS ASSOCIATES

Charles Adams

Ely Brayboy

Charles Capstick

Cannon Caspar

Morgan Dethlefsen

Peter Edelstein

Ellyse Givens

Anna Lister

Nicolas Pereira-Arias

Martin Pohlen

Eloise Robertson

Talia Sawiris

Hannah Severyns

Issue 01, Fall 2022 Masthead

Alexandra Mork

Hai Ning Ng

Uprooting

Sarah Roberts

The Scars Issue Brown Political Review Interview: Eileen Appelbaum United States

Ackerman

Stern Elijah Dahunsi Maddock Thomas Leaving Legacies Behind Waking Up From Pipe Dreams Interview: Young Mie Kim You Can’t Just Reform Colonialism 7 13 14 16 20 22 9 10

in Plain Sight

Ben

Zach

Lauren Griffiths Hyding

Interview: Kiki Louya

Insecurity

Special Feature: Scars

Corrupt Coalition

Nealie Deol

Somalia Syndrome

Ian Stettner

Francisca Saldivar

Down Goes Tangier

William Forys

Elliot Smith

Borderline Raiders of the Lost Art

Grace Chaikin

Interview: Ashley Mears

Alyssa Merritt

David Pinto

Interview: Nicholas Kulish

Mira Mehta

Bianca Rosen

Julia Kostin

Interview: Ethan Nadelmann

Alex Fasseas & Elise Curtin

Soccer Offers a Shot at a Bigger Goal A Rose By Any Other Name Everyday

Isabel Greider

Issue 01, Fall 2022 Table of Contents World

He’s Hustlin’

Overruling Insular Cases 26 38 34 47 36 48 50 52 54 28 42 30 44

Ego, ENLARGED

Leaving Legacies

A unique opportunity to reform college admissions

by Ben

The Supreme Court is poised to rule that affirmative action is unconstitutional after hearing a pair of cases on the subject this fall. If the Court makes such a ruling, colleges and universities should seize the opportunity to institute comprehensive admissions reform. Affirmative action is unpopular and possibly unconstitutional, but athletic commitments and legacy admissions are similarly problematic and should be eliminated as well. There is little reason to believe that these policies are necessary to produce an exceptionally qualified and diverse student body. In their place, colleges and universities should pursue a model prioritizing academic merit alongside consideration of unique backgrounds and perspectives.

The admissions practices of colleges and universities, particularly “elite” ones, draw frequent fire from both ends of the political spectrum. Liberals focus on the inequity of legacy preferences and athletic admissions, which they argue perpetuate racial and socioeconomic inequality. Conservatives, on the other hand,

argue that race-based affirmative action policies are inherently racist, counterproductive, and unconstitutional. Opinion polling suggests that affirmative action, legacy admissions, and athletic recruitment are unpopular with most Americans. Even in the face of all this criticism, elite colleges and universities like Brown continue to defend their admissions practices, arguing that they are necessary to protect diversity and foster strong alumni relationships.

This fall, the Court will hear two cases directly challenging affirmative action. Students for Fair Admissions, a group opposing affirmative action, has sued both Harvard University and the University of North Carolina. It argues that racial preference policies violate Title VI of the Civil Rights Act, and judging by past decisions, it appears Chief Justice John Roberts and other members of the Court’s conservative majority agree. In Parents Involved in Community Schools v. Seattle School District 1, Roberts famously held “the way to stop discrimination on the basis of race is to stop discriminating on the basis of race.” Justices Thomas, Alito, and Kavanaugh have similarly expressed their skepticism toward racial preferences, and given the current makeup of the Court, an outright ban on racial preferences in admissions is a strong possibility.

Despite issues in their implementation, affirmative action policies were born out of a commendable desire to rectify America’s deeply ingrained history of systemic racism and pro-

Behindmote diversity on college campuses. Defending the continued use of racial preference, Brown University President Christina Paxson argues that race represents a “really important piece of information about a person in the life that they’ve experienced.” Yet, race is just one facet of an individual’s lived experience. Racial background does not automatically consign someone to a given perspective. Other factors like socioeconomic class, geography, and family structure can be equally fundamental. For many candidates, race may be fundamental to their identity, but for others, it could be tangential. Making assumptions about an individual’s lived experience based on the boxes they check on paper is lazy policy at best, and racist at worst.

One could argue that it is also entirely unnecessary. College applications already give applicants ample opportunities to demonstrate their diverse perspectives via personal essays and activity descriptions. By comprehensively evaluating each candidate’s unique identity, schools should be able to assemble a diverse array of backgrounds without considering an applicant’s race as part of their application.

If affirmative action is eliminated, athletic commitments and legacy preferences should follow. Elite colleges and universities downplay the importance of athletics or legacy status in admissions, but research suggests that both can play a much larger role than administrators care to admit. Admissions data from Harvard, published in the ongoing lawsuit, is staggering. One model suggests that from 2014 to 2019, legacy candidates and athletic recruits enjoyed an increase in admissions odds by factors of eight for legacy students and five thousand for athletes. Another study, from 1983-1997 of other elite research universities showed those candidates enjoyed more modest admissions odds increases of three (legacy) and four (athletes) times.

It is unclear why elite schools sacrifice academic standards to extend commitments to athletic recruits. Ivy League recruits are technically subject to the same admissions process as regular candidates, but coaches can extend “likely letters,” a massive boost to admissions chances. One study finds that at top research universities,

THE SCARS ISSUE 7

“Opinion polling suggests that affirmative action, legacy admissions, and athletic recruitment are unpopular with most Americans.”

Ackerman ’24, a Political Science concentrator and a Content Editor for BPR illustrations by Jocelyn Chu ’23, a Biophysics concentrator

the athletic admissions advantage is roughly equivalent to a 200-point increase in SAT score. At Harvard, data suggest that the academic credentials of a non-athlete candidate with a 1% chance of admission would have a 98% chance of admission as an athlete with their same academic credentials. One justification for this disparity may be that recruits devote a large portion of their time to their sport, explaining their relative shortcomingsvv in the classroom. Indeed, exceptional achievement on the field, court, or ice is a clear demonstration of dedication and non-academic merit which ought to be considered in college admissions. However, the same is true for any candidate with significant extracurricular pursuits. It is wholly unfair that an athlete can subvert college admissions standards, while a world-class violinist, accomplished community organizer, or champion-level debater receive no similar advantage.

To make matters worse, given the extremely expensive nature of American youth sports, athletic commitments favor individuals with access to expensive club lacrosse teams, personal pitching coaches, or private squash clubs to train at. As such, athletic recruitment perpetuates a pipeline from privileged prep schools to elite colleges and universities. Granted, athletics can certainly be a valuable part of a col-

lege experience or school culture. But this can remain true without admissions commitments, which result in Ivy League athletes academically underperforming. MIT, for example, extends no “likely letters” or any other form of admissions commitments, yet maintains 33 varsity athletic programs. Other top colleges and universities should follow suit—keep the sports teams, drop the commitments.

Similar to athletic admissions, legacy admissions serves a privileged class of applicants. At Harvard, the acceptance rate for legacy students from 2014 to 2019 was 33%, dwarfing the overall 5.5% acceptance rate during that period. Even though legacy applicants are more likely to be wealthy and white compared to the average candidate, administrators like President Paxson and Brown University Dean of Admissions Logan Powell defend their special treatment. Legacy status, they promise, is only a “minor” piece of a much larger puzzle that admissions officers consider. Even if true, this does nothing to absolve the practice. Few would or could defend racism or sexism in a hiring process by claiming that it was only a “minor factor.” To properly justify legacy preference, universities must provide a compelling reason. Some argue that financial considerations are at play—yet evidence suggests that legacy admissions does not impact alumni donor behavior. Rather, legacy admissions are a relic of an era in which universities functioned largely as prestige propagators and have no valid place in the current admissions landscape. Several top schools have already recognized this and moved to eliminate the practice—MIT, Amherst, and the University of California system, to name a few. Brown should be expected to follow suit.

By moving beyond affirmative action, legacy preferences, and athletic commitments, colleges and universities can remake their admissions processes in a more equitable mold. A federal ban on affirmative action presents a chance for comprehensive admissions reform— colleges and universities must seize the opportunity.

FALL 2022 | ISSUE 01 8 UNITED STATES

“Other top colleges and universities should follow suit—keep the sports teams, drop the commitments.”

Zach Stern (ZS): What prompted you to start Project DATA?

Young Mie Kim (YMK): For almost my entire career, I have been studying passionate publics: people who care about political issues because of their particular values, identities, or interests, like those who care about the abortion issue because of their religious beliefs. I realized that these people tend to put their issues ahead of their political party identification and that they tend to distrust mainstream media, opting instead to spend a lot of time on social media platforms like Facebook. They’re mobilized because of the issues they care about, and in the data-driven, algorithm-based digital age, I realized that political leaders and campaigns try to identify these passionate people using data and microtargeting tools because it’s much easier for political campaigns to persuade people who are very passionate about particular issues given their personal concerns. These groups are scattered around the country, so it has traditionally been hard to identify and mobilize them, but with microtargeting tools, you can now do just that. I realized that studying advertising—the outcome of every deliberate strategy—would be a good way to examine how political campaigns identify these people and come one step closer to understanding the strategies and tactics that they use.

That’s why I started this project, but I quickly realized that political ad data on social media is not publicly accessible. Even when Congress investigated Russian election interference after the 2016 election, they relied entirely on data that the platforms voluntarily handed over to them, so I hired a computer scientist and developed an app that tracks digital political ads across social media platforms—a user-based and real-time reverse-engineered

Disinformation and Democracy An Interview with Young Mie Kim

Young Mie Kim is a professor at the School of Journalism and Mass Communication and an Andrew Carnegie Fellow at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. Professor Kim’s research centers on the influence of digital media on political communication in contemporary media and politics across political campaigns, issue advocacy groups, and voters. Professor Kim’s most recent project, Project DATA, employs a real-time, userbased ad tracking tool to study the sponsors, content, targets, and algorithms of online political campaigns across social media platforms. The project analyzes the often obscured operations of digital campaigns while highlighting pernicious microtargeting practices.

tracking tool that would allow us to track who sent ads and captured ad content. In addition to the app, we also surveyed users on their demographics and their political attitudes so that we could reverse-engineer how the ads targeted particular groups and build targeting profiles for political ads. It is very important to have an independent investigator outside of the tech platforms, and this project collects data independent of these tech platforms through our user-based app.

ZS: How has the project developed from its first election cycle in 2016 to the 2018 and 2020 elections?

YMK: I started this project to investigate how passionate publics are identified, targeted, and mobilized on political platforms by political campaigns, and initially, I ran a candidate campaigns analysis, looking, for example, at Hillary Clinton and checking how many ads matched in our dictionary. We realized that many ads had unidentifiable sponsors, so we tracked the landing pages of these ads to identify the sponsors. But half of the sponsors we examined were still not identifiable because they were not registered with the Federal Election Commission. Some nonprofits are exempted from disclosure requirements, but if this were the case we should have been able to find them in the IRS data that we looked through. Still, half of the sponsors were not identifiable, so we left them aside because there was nothing to do. Then, one year later, the House Intelligence Committee released meta-information on Russian ads, and after matching this data with the landing pages from our data, many of the suspicious groups that we identified turned out to be Russian groups. Since then, our research has become more forensic, trying to identify

the strategies and tactics of Russian actors and Russian election interference patterns. We then realized that domestic actors also used similar techniques, so we have been trying to understand the relationship between domestic and foreign suspicious groups.

ZS: What do you think Congress could and should do to combat the spread of false information and online voter suppression on platforms like Facebook?

YMK: We have laws and policies that can regulate online disinformation, including election interference, but these policies are so outdated that they don’t adequately regulate disinformation on these platforms. We need ad archives, for example, that include targeting method and targeting information so that the voters can decide whether to trust particular information. The Facebook whistleblower, Frances Haugen, also pointed out that we need greater algorithm regulation and transparency. Without adequate regulation, we’re going to have very limited solutions. There are a number of different ways you could do that. Some people argue for algorithm auditing by a third party or agency. Australia recently passed a bill that requires Google, Facebook, and other large tech platforms to share how they formulate their news recommendation system and then share that information with major news organizations, since people now find these stories on social media rather than directly from news websites. That market-intervention kind of regulation is one example, but there are a number of different ways you could work the algorithm component.

Edited for length and clarity.

FALL 2022 | ISSUE 01 9

Interview by Zach Stern ’22

Illustration by Christine Wang ’24

INTERVIEW

You Can’t Just Reform Colonialism

by Maddock Thomas ’26,

Economics

Staff Writer

Puerto Rico is one of the most diverse and culturally rich parts of the United States, with a population equivalent to the 32nd most populous state. Puerto Rico, however, is also a US colony and home to the nation’s second-largest police department, after the New York City Police Department (NYPD). The Puerto Rico Police Department (PRPD) is not only large, but it is also deeply corrupt and repressive. It has spent the past century overseeing mass surveillance of pro-independence activists, jailing journalists, and violently suppressing peaceful protests. Founded as the Insular Police to protect American interests in Puerto Rico, the PRPD continues to serve that purpose today, albeit with a change of name. Not only do the police serve to maintain the current colonial order, but they also actively contribute to criminal activity on the island.

The PRPD’s predecessor, the Insular Police, was established under the Bureau of Insular Affairs, a bureau within the United States War Department. From its inception, the Insular Police, which remained a quasi-military organization until 1996, was tasked with repressing Puerto Rico’s supporters of independence, the “independistas.” The police notoriously imprisoned journalists who questioned the US occupation of Puerto Rico, illegally gathered carpetas (or files) full of personal information on tens of thousands of Puerto Ricans with intent to blackmail, and responded violently to protests. One of the most infamous events in Puerto Rican history is the 1937 Ponce Massacre, during which police fired on unarmed marchers, kill-

ing 19 and injuring over 100. The PRPD has also collaborated with the FBI to attack left-wing movements by supporting right-wing terrorism during the 1960s–1990s.

Now, as a civilian organization in the 21st century, the PRPD continues to act militarily to suppress protests challenging the colonial status quo. The PRPD regularly responds to peaceful gatherings with excessive force, violating the First Amendment. In fact, a report published by the Department of Justice (DOJ) outlines that the PRPD is “broken in a number of critical and fundamental respects.” In addition to suppressing political freedom, the PRPD is one of the most violent entities in the United States. According to the ACLU, the PRPD was responsible for three times more civilian deaths than the NYPD between 2007 and 2011, despite New York City having twice the population.

FALL 2022 | ISSUE 01 10 UNITED STATES

Transforming the Puerto Rican Police Department requires challenging the imperial order

“Not only do the police serve to maintain the current colonial order, but they also actively contribute to criminal activity on the island.”

an intended

and Applied Mathematics concentrator and a

for BPR illustrations by Lucia Li ’24, an Industrial Design major at RISD

The PRPD’s blank check to enforce the colonial status quo has also led to deep-seated corruption and impunity from the law within the force. As the DOJ report states, “More PRPD officers are involved in criminal activity than in any other major law enforcement agency in the country.” In fact, during the period from 2005 to 2010, more than 1,700 PRPD officers were arrested for criminal activity. And this is considered a significantly lower number than the actual crimes committed by officers. This inadequate records management is unsurprising for the department: During their “Mano Dura contra el Crimen” (“hard on crime”) program in the 1990s, the PRPD went from over-reporting to under-reporting homicides by a margin of more than 100 deaths per year to make its program appear successful rather than harmful. The PRPD frequently lies on reports to hide the department’s failngs.

Yet the PRPD’s repressive, violent behavior described by the DOJ was not news to those who had been targeted by it. A student leader at the University of Puerto Rico, where peaceful protests had been broken up using clubs and pepper-spray, responded to the report, asking “Who in Puerto Rico doesn’t know that the Puerto Rico Police Department does this daily?” This report succeeded in bringing the issues with the PRPD to the attention of the mainland, where the ACLU lobbied for reform. As a result, the PRPD entered into a 10-year consent decree and com-

THE SCARS ISSUE 11

“The failure to reform the PRPD is a disheartening symptom of the continued hold of the United States on Puerto Rico. So long as the PRPD continues to uphold the colonial order, the United States has no incentive to reform the agency.”

prehensive reform deal with the DOJ in 2015. Though the reform was hailed as “historic” by the ACLU, the department’s fundamental role in reinforcing existing systems of power—including US colonial dominance—quickly came into conflict with the requirements of reform. The federal government had forced the PRPD into the reform program originally, but it appears to have quickly lost interest in carrying out the reforms it outlined. The federally-appointed monitor for the reform program, Arnaldo Claudio, recalls submitting eight reports during his tenure about the continued illegal use of force and constitutional civil rights violations by the PRPD. The federal government provided him no support. In May of 2019, after almost five years directing the effort to reform the PRPD, Claudio resigned, saying, “I don’t want to be associated with such a system. There is something called resignation and something called ethical and moral values.”

In June, shortly after Claudio’s resignation, protests swept the island following a leaked text chat involving then-Governor Ricardo Roselló revealing corruption and deep-seated misogyny in Puerto Rico’s government. Notably, the chat also corroborated Claudio’s accusations that the federal government had no desire to reform the PRPD. As Marisol Lebrón, an Associate Professor at the University of California, Santa Cruz whose work covers Puerto Rican policing, describes, “The chat itself reveals that for the past five years, the federal government did not work with the local authorities [...] to address police repression or stop human rights abuses.”

Unsurprisingly, in response to these mass protests, the police were soon deployed. Despite supposed sweeping reform, they turned to century-long tactics of violence and colonial repression. During one protest, the police were heard shouting “Su actividad ha dejado de estar protegida por la Constitución” (“Your actions are no longer protected by the Constitution”) before tear-gassing protestors, beating them with clubs, and shooting them with rubber bullets.

The continued failure to reform the PRPD is a disheartening symptom of the continued hold of the United States on Puerto Rico. So long as the PRPD continues to uphold the colonial order, the United States has no incentive to reform the agency. It is therefore necessary to change the colonial condition in order to address police violence in Puerto Rico and bring actual safety to Puerto Ricans. However, any such change will be violently opposed by the PRPD, as it has been for over a century. This seemingly irreconcilable situation does not mean change is impossible, but thanks to the PRPD and its approval from the United States, the decolonization of Puerto Rico will be no easy task.

FALL 2022 | ISSUE 01 12 UNITED STATES

“In fact, during the period from 2005 to 2010, more than 1,700 PRPD officers were arrested for criminal activity. And this is considered a significantly lower number than the actual crimes committed by officers.”

Elijah Dahunsi (ED): For our readers who may not be familiar with finance or economics, what exactly is private equity (PE)?

Eileen Appelbaum (EA): A PE firm is a type of Wall Street investment firm that sponsors investment vehicles known as funds. One of the partners of a private equity firm is the general partner. The general partner makes all the decisions for the fund, in addition to recruiting potential investors. These other investors are called limited partners.

The general partner representing the private equity firm puts in one to two cents for every dollar that the limited partners put in. It’s important to note that once investors invest in the fund, they have no say over what is done with the money. Rather, the general partner and the employees of the fund go looking for prospective companies to buy. PE funds finance these purchases with a combination of debt and money invested in the fund. Sometimes these companies survive, and sometimes they don’t.

ED: What specific motivations draw PE firms to the healthcare industry?

EA: PE firms have, relatively speaking, only recently gotten into healthcare, choosing to initially buy hospitals. A main motivation for these purchases was the passage of Obamacare. Though many political observers harbored doubts about the bill’s ability to pass, executives in PE were confident that the bill would pass and be fully implemented. Acting on this confidence, many PE firms purchased hospitals with the intention of capitalizing on cash flows from Medicare, Medicaid, and the VA (Veterans

Healthcare for Sale An Interview

with Eileen Appelbaum

Dr. Eileen Appelbaum is the co-director of the Center for Economic and Policy Research, Washington, DC; a fellow at the Rutgers University Center for Women and Work; and a visiting lecturer at the University of Leicester. Her research focuses on the effects of organizational restructuring on firms and workers, private equity and financialization, and work family policies. Her book, Private Equity at Work: When Wall Street Manages Main Street, coauthored with Rosemary Batt, was named a finalist for the 2016 George R. Terry Award and one of the four best books of 2014 and 2015 by the Academy of Management.

Affairs) system—government agencies that account for 50 percent of all healthcare costs. So PE involvement in healthcare is essentially taxpayer-financed capitalism.

Some prominent PE firms involved in this hospital investment scheme were Cerberus and Leonard Green. Despite owning so many hospitals, these firms did not make a considerable amount of money running them. Instead, they made most of their money by stripping the hospitals of their real estate, selling this real estate, taking the cash, and leaving hospitals to pay rent to a Real Estate Investment Trust (REIT). These REITs owned the properties and buildings that purchased hospitals had previously owned. PE firms made money from these REITs through dividend recapitalizations—a process where purchased companies pay dividends to PE firms with cash accrued from high-interest junk bonds.

In the case of purchased hospitals, this increased debt limited profitability. When these hospitals predictably began to struggle, vulnerable communities were negatively affected. These include white communities in rural areas and Black communities in inner cities. It was just unconscionable.

Eventually, the instability of Medicare and Medicaid rates disincentivized PE firms from buying hospitals. To accrue more stable revenue streams, PE firms instead turned to physician practices. These practices, unlike Medicare and Medicaid, enabled PE firms to make money through fixed contracts with hospitals.

PE firms focused their purchasing efforts on practices associated with medical specialties where patients had a higher degree of fully

complying with treatment. These specialties include emergency medicine, radiology, and anesthesiology. To expand their control in these specialties, PE firms, like Blackstone and KKR, sponsor large companies, such as TeamHealth and Envision, respectively, composed of physician practices. Once a practice is purchased by a PE-owned company, the company, which exists outside insurance networks, has complete control over the billing of the practice.

ED: So how do you best regulate against the growing influence of private equity in healthcare?

EA: There’s a legislative remedy that controls surprise medical bills which passed in a bipartisan manner in both the House and the Senate in December of 2020. This mainly benefits those under private insurance because Medicare and Medicaid already control unexpected medical bills. Another legislative proposal made by Elizabeth Warren—The Warren Stop Wall Street Looting Act—would reform the WARN Act, making workers’ pay the foremost priority in cases of bankruptcy.

There are also regulatory opportunities at the state level. Many hospitals in this country are nonprofit hospitals that do not pay taxes. If these hospitals are bought by for-profit companies, state attorneys general can find ways to make these hospitals give back to the community. This happened in Rhode Island. As a result, the two hospitals in Rhode Island have a good chance of surviving.

Edited for length and clarity.

FALL 2022 | ISSUE 01 13

Interview by Elijah Dahunsi ’25

Illustration by Christine Wang ’24

INTERVIEW

Waking Up From Pipe Dreams

The dangers of carbon capture

by Lauren Griffiths

by Lauren Griffiths

The residents of Yazoo County, Mississippi were confronted with a danger the world had yet to behold in February 2020: a carbon dioxide (CO2) pipeline explosion. Within minutes, residents were dazed, foaming at the mouth, and left unconscious by the green cloud sweeping over their town. Individuals who were not too disoriented to walk scrambled to their cars—the most logical escape route. Those who made it as far as their vehicles were met with the frightening realization that the gas had paralyzed their cars’ engines. They were trapped.

While this was the first noted instance of mass outdoor exposure to piped CO2, it is unlikely to be the last. The tragedy of Yazoo County is a clear warning sign of the United States’s unpreparedness to handle a CO2 pipeline network expansion, which recently passed legislation is destined to bring.

The Yazoo County explosion occurred after a 24-inch pipeline carrying concentrated CO2 and hydrogen sulfide ruptured in a heavily wooded area near the town of Satartia, Mississippi. While CO2 is commonly thought of as harmless, at high concentrations it displaces oxygen from the air, causing asphyxiation in humans and preventing cars from burning fuel. The fossil fuel company that operates the pipeline, Denbury Inc., had taken little action to warn the community about this potential danger. For 15 minutes, even Denbury workers themselves did not realize that the fog from the explosion was CO2.

CO2 leaks had also not been on the radar of the nearby firefighters, sheriffs, or hospital staff, particularly troubling given that 49 indi-

viduals were hospitalized due to asphyxiation. Thankfully, although residents still report lingering physical and mental impacts from the explosion—such as lung dysfunction, stomach disorders, and mental fogginess—there were no fatalities. As far as pipeline explosions go, Yazoo is lucky. Many of America’s pipelines lie much closer to towns than the one near Satartia. Moreover, many of these towns have populations significantly larger than that of Satartia. Additionally, the Denbury rupture happened at 7:00 in the evening, when people were awake and responsive to both their surroundings and local authorities. Had the explosion happened just a few hours later, rather than breathing apparatuses, first responders might have needed body bags.

Such a scenario could take place in the future preventative action is not swiftly taken. A

report published in March 2022 by the Pipeline Safety Trust (PST), a prominent pipeline safety group, warned that the nation’s CO2 pipeline regulations are dangerously insufficient and fail to address public safety risks. This report was published in response to a rush of multibillion-dollar CO2 pipeline projects following the Bipartisan Infrastructure Bill’s vast allocation of funding to the carbon capture and storage (CCS) industry. The PST’s report urges the US Department of Transportation’s Pipeline and Hazardous Materials Safety Administration (PHMSA)—the agency with authority over CO2 pipeline safety—to update its regulations as soon as possible.

As we await these updated regulations, new pipelines are being planned in populated areas, posing a risk to the surrounding communities and raising significant concerns regarding envi-

FALL 2022 | ISSUE 01 14 UNITED STATES

’24, an Environmental Studies and International and Public Affairs concentrator and an Associate Editor for BPR illustrations by Jason Aragon ’24, an Illustration major at RISD

ronmental justice. Hazardous waste facilities and fossil fuel extraction, processing, and transportation infrastructure have often been located near marginalized communities. Therefore, it is reasonable to worry that CO2 pipeline pathways could follow similarly harmful patterns if environmental justice is not centered during the CCS expansion process. Major pipeline proposals also currently face opposition from landowners and advocacy groups, as these projects require companies to build through private property and residential communities, displacing some and endangering others. Community members fear not only for their personal safety in the aftermath of the Satartia explosion, but also for their livelihoods: Soil and water contamination pose serious threats to crop security. Their resistance has increased the difficulties developers encounter when acquiring voluntary agreements with landowners for pipeline rights-of-way through their properties. Nevertheless, developers can still obtain rights-of-way via eminent domain authority, which typically involves receiving siting permits from state utility regulators. This example, in addition to the necessary preparations of states and communities for potential pipeline leakages, exemplifies the large role of local and state authorities in dealing with CCS expansion. States and municipalities must recognize the importance of CO2 pipeline safety and act accordingly. With the power to implement their own pipeline regulations, swifter implementation capacities, and a better understanding of their communities’ needs, state governments should pursue the recommendations outlined by the PST and provide support for municipalities to institute emergency preparedness procedures as soon as possible.

On the federal level, the PHMSA responded to the Yazoo explosion by announcing new safety measures in May 2022 intended to protect Americans from similar failures. The recommendations include research solicitations to strengthen CO2 pipeline safety; the encouragement of pipeline operations to plan for risks that could threaten pipeline integrity; and the development of updated standards for CO2 pipelines, which contain requirements for emergency preparedness and response. While it is a critical step forward, this announcement is just that: an announcement. It does not guarantee implementation of the crucial regulatory changes proposed by the PST nor does it acknowledge the necessity of funding for local towns and municipalities to properly set up preparation mechanisms. Only stringent regulations on both the federal and state levels can ensure all potentially impacted communities are equipped to respond. The upcoming regulations should ensure such preparations never need to come into play.

The lack of awareness and preparation for this potential danger is especially frightening considering recent investments to expand our nation’s CO2 pipeline network. The Inflation Reduction Act enables a large upscaling of the carbon capture industry through updates to the 45Q tax credit, which incentivizes the use of carbon capture and storage. By increasing the government subsidy from $50 to $85 per metric ton, CCS is now much more financially viable for producers. Last year’s Bipartisan Infrastructure Bill provided $100 million to the Department of Energy to design a pipeline network to transport compressed CO2 emissions to underground storage sites, $2.1 billion in loans and grants to build said pipelines, and $3.5 billion to construct four atmospheric CO2 removal facilities. All this means that the industry could grow 13-fold by 2035. For many years, concerns about the United States’ limited preparation for CO2 pipeline emergencies were simply passing wonderments of distant futures. Now that the country has made significant strides in climate change policy, these casual hypotheticals are becoming dangerous realities.

While the country’s groundbreaking climate legislation should be lauded, it must be coupled with regulations to address the risks that accompany CCS expansion. Agencies like PHMSA are in the process of updating regulations, but further steps must be taken to fund local emergency response teams, implement additional local and state regulations, and reduce the public safety risks to surrounding communities. In doing so, we can prevent disasters like the one in Yazoo County.

THE SCARS ISSUE 15

“Had the explosion happened just a few hours later, rather than breathing apparatuses, first responders might have needed body bags.”

Hyding in

Plain Sight

How the Hyde Amendment quietly undermines reproductive freedom and what states can do to fix it

by Alexandra Mork ’25, a Political Science and History concentrator and a Managing Editor and Staff Writer for BPR

Infographics by Hannah Jeong RISD ’26 and Icy Liang ’25

“I’m not going to be able to do anything more… this is my only option,” a single, working mother of three told a phone counselor at the Women’s Medical Fund in November of 2017. With only $125 in savings, she was forced to turn to a private abortion fund to help pay for expenses that her insurance would not cover and her family could not afford. Tragically, stories like this one are not uncommon. Worse, some women are altogether unable to access reproductive healthcare during their pregnancies, leading to forced births.

Forced birth is gendered violence. First and foremost, it is a clear violation of bodily autonomy. Beyond that, it also traps people in cycles of structural violence from which they have little hope of escape. The Guttmacher Institute reports that “women who do not obtain an abortion they wanted have four times greater odds of subsequently living in poverty and three times greater odds of being unemployed six months later, compared with women who are able to obtain an abortion.” Moreover, women forced to carry unwanted pregnancies to term experi-

ence higher rates of medical complications and chronic pain, as well as worse health outcomes overall than those who receive their desired care.

Prior to the Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization Supreme Court decision, the United States federal government protected people’s fundamental right to choose. But for many, this was a right in name only. The stories of people who struggle to pay for reproductive care are too often left untold—they are confined to the solemn halls of doctors’ offices, desperate phone calls with help lines, and hushed conversations with loved ones. Nevertheless, these stories are all around us.

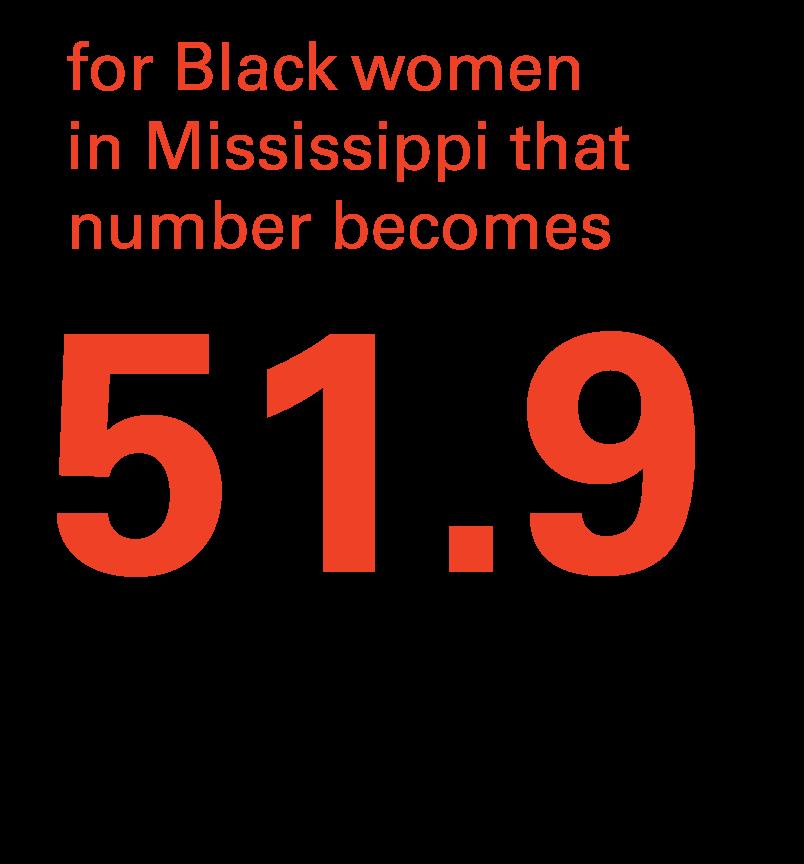

This silent suffering is not inevitable. The federal government once funded over 300,000 abortions annually through Medicaid, a program which provides health insurance to roughly 80 million mostly low-income Americans. But in 1980, that number dropped to almost zero. The cause of this precipitous decline? The implementation of the Hyde Amendment.

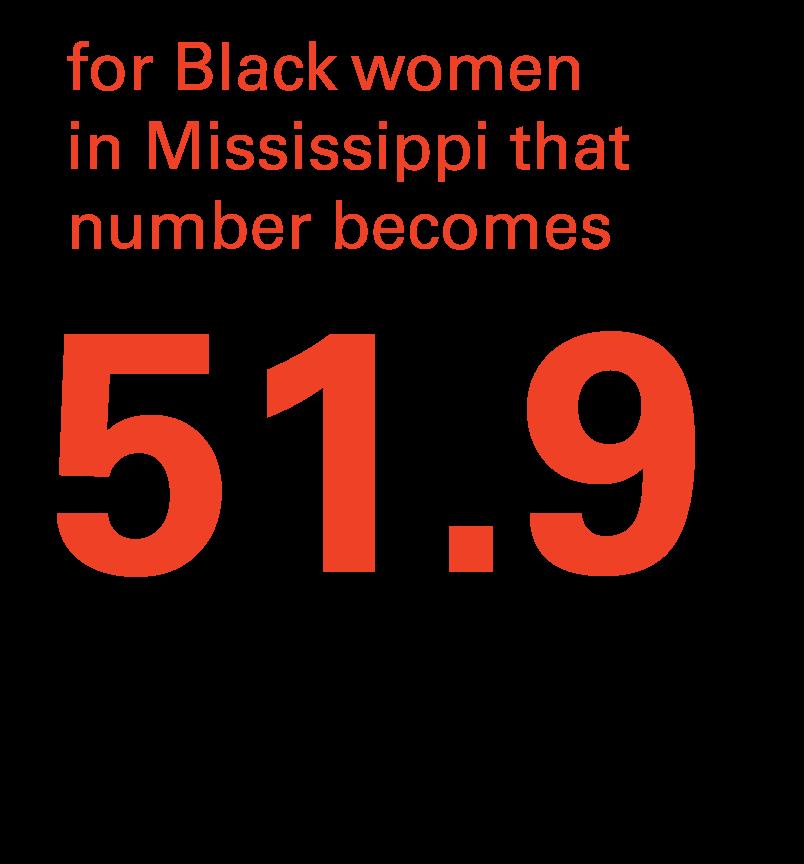

Included in annual appropriation bills since the 1970s due to pressure from pro-life members of Congress, the Hyde Amendment prohibits the use of federal funds to cover abortions. This means people on Medicaid or the Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP) must pay for abortions out of pocket. This restriction places an undue burden on those who are precisely the least able to afford it: One-half of all the women and girls of reproductive age who live in poverty are enrolled in Medicaid. For these individuals,

FALL 2022 | ISSUE 01 16 UNITED STATES

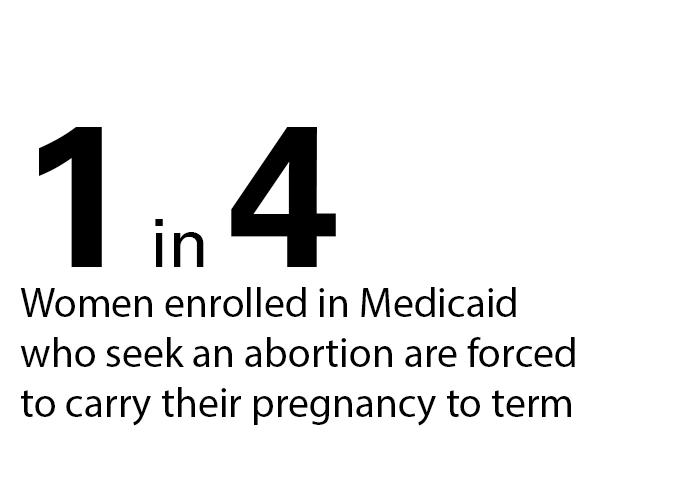

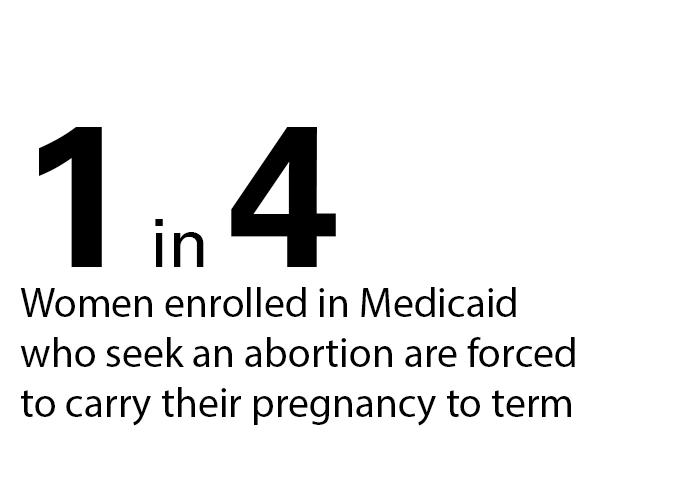

paying hundreds or even thousands of dollars is a huge, often insurmountable barrier to receiving care. Consequently, in states that do not fund reproductive healthcare themselves, one in four women on Medicaid who seek abortions are ultimately unable to obtain them.

A congressional repeal of the Hyde Amendment would be the most effective way to minimize forced birth across the nation and help ensure that all people—regardless of income, veteran status, or incarceration—have the right to choose. However, such a repeal currently faces an uphill battle in the Senate due to

united Republican opposition, as well as pushback from a few Democrats. Thus, one critical near-term goal for reproductive rights activists should be pressuring states to cover the costs of abortions for people on federal insurance.

While some states already cover abortion costs, the majority do not—nearly eight million women across 34 states and the District of Columbia are directly affected by the Hyde Amendment. And in Colorado, Delaware, Nevada, and Rhode Island, Democrats have failed to act in spite of the fact that they hold trifectas in state offices.

Far too often, even women who are able to get abortions must do so at great personal cost. In one study, more than half of participants spent over one-third of their monthly income on the procedure, with many delaying paying their bills or foregoing meeting their material needs. And even with these sacrifices, over half of the women in the study were forced to defer their

THE SCARS ISSUE 17

“Prior to the Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization Supreme Court decision, the federal government protected people’s fundamental right to choose. But for many, this was a right in name only.”

abortions to raise money for their procedures. These delays not only raise the costs of the procedure itself, but also increase the likelihood of medical complications.

While some postpone or forego care, others, like Rosie Jimenez, resort to unsafe methods. When the Hyde Amendment took effect, Jimenez was a 27-year-old college sophomore on Medicaid. Because her insurance would not cover the costs of her abortion, Jimenez could not afford to see an OB/GYN to obtain the procedure. So, lacking other options, she turned to an unlicensed midwife. After days of bleeding, Jimenez died of an infection, leaving behind her four-year-old daughter.

Jimenez’s widely publicized story has led her to be called the “first victim” of the Hyde Amendment—but she was certainly not the last.

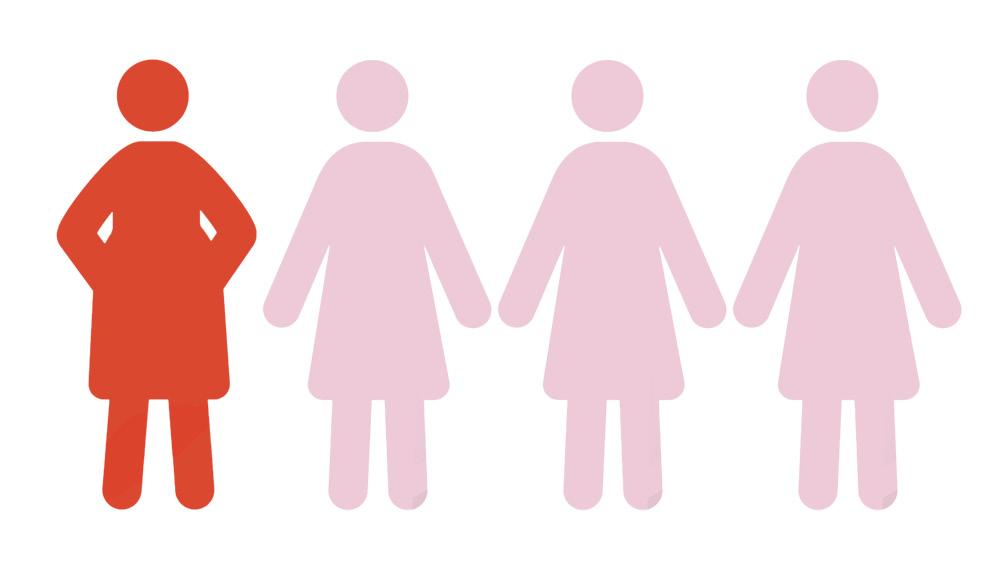

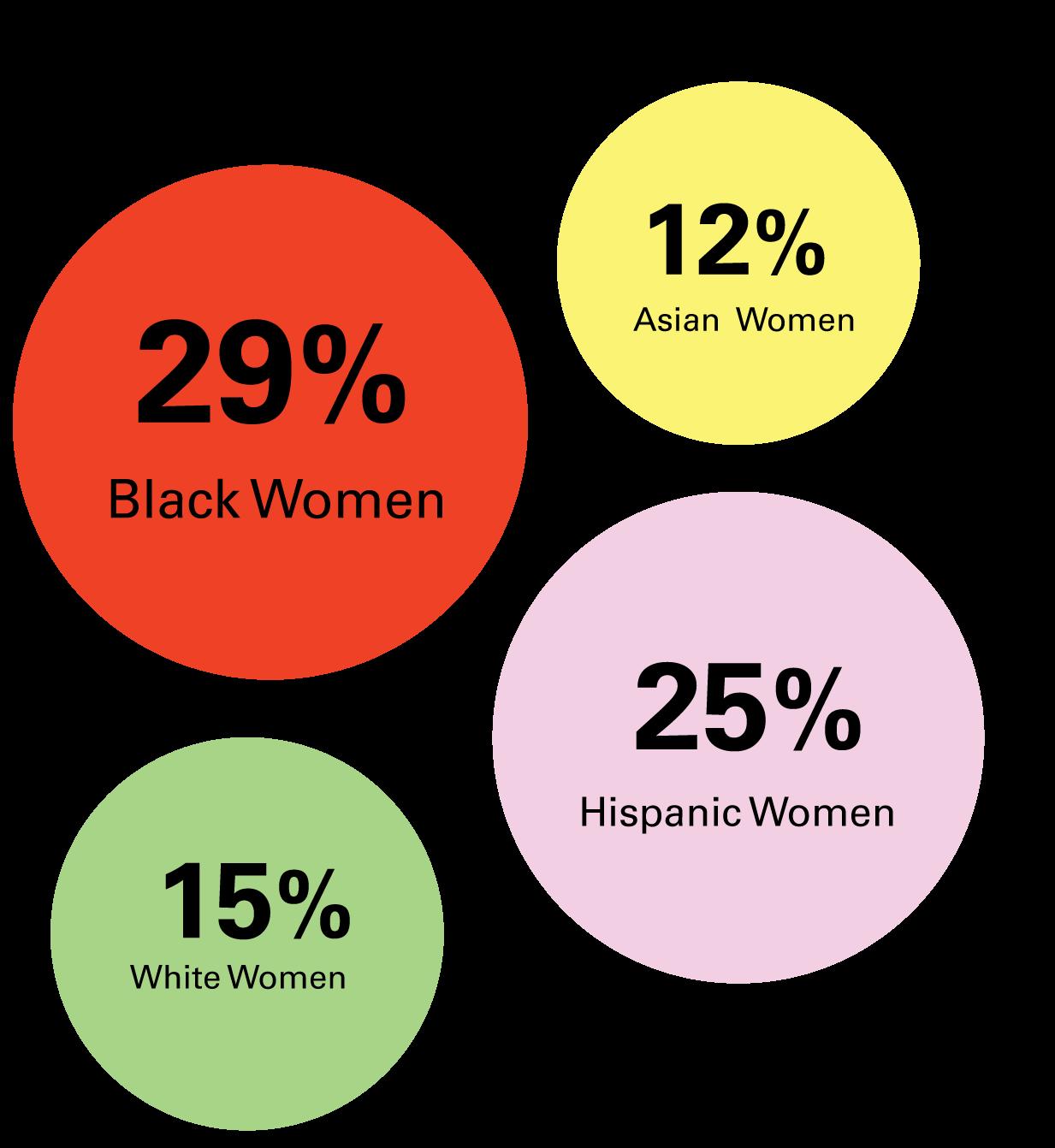

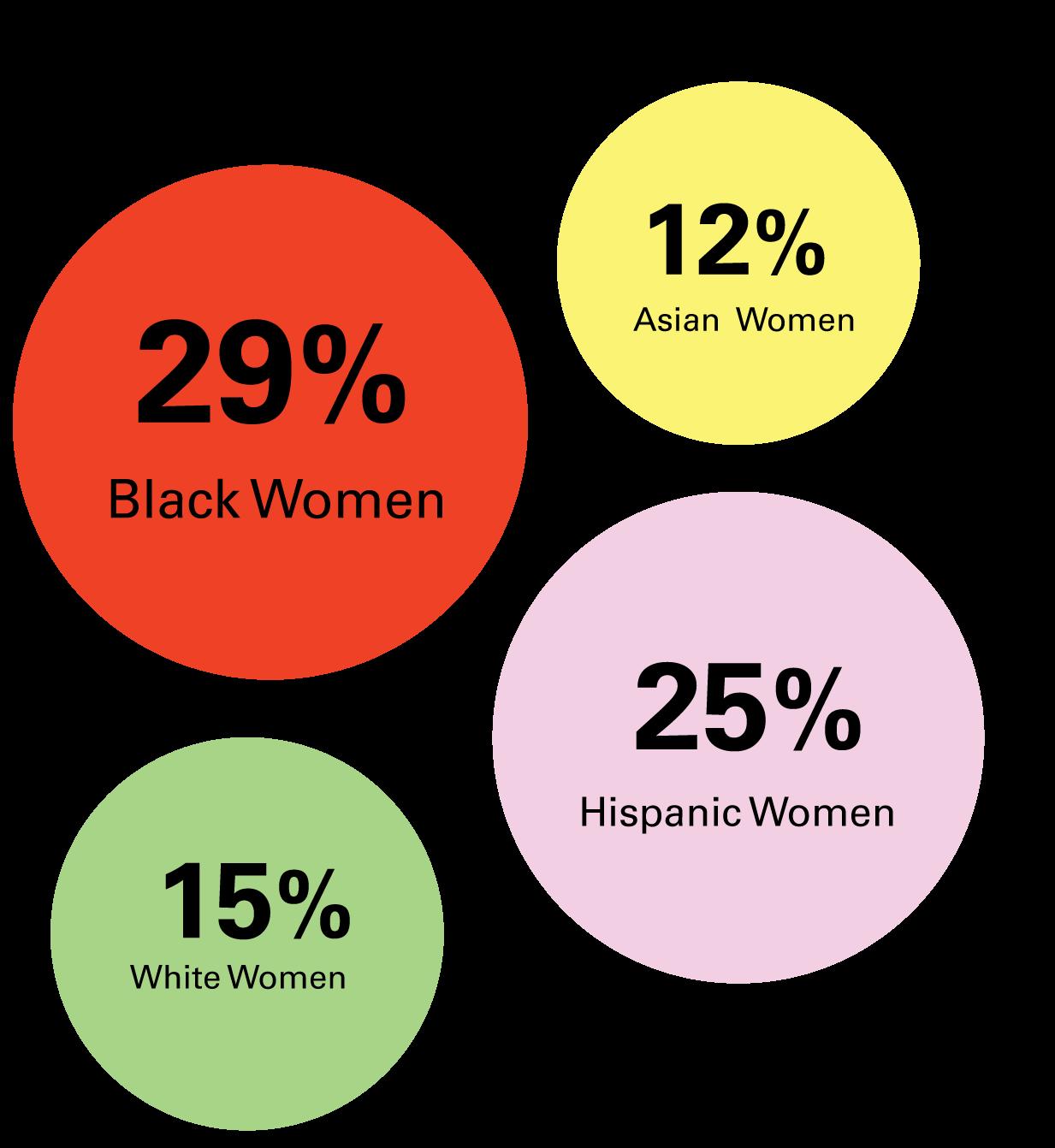

And because of the intersections of race, gender, and poverty, repealing the Hyde Amendment is an issue of social as well as economic justice. Nearly 30 percent of all Black women between 15 and 49 were enrolled in Medicaid in 2019, and Black women seek abortions at higher rates than their non-Black counterparts. Furthermore, Black women experience disproportionately high rates of maternal mortality when they carry pregnancies to term. Together, these facts illustrate a harrowing reality: Black women are disproportionately likely to seek access to abortion care, disproportionately likely to be denied such access, and disproportionately likely to suffer the consequences of those denials.

The Hyde Amendment also hurts other groups who rely on federal funding for their insurance, including many government employees, veterans, federal prisoners/detainees, and Native Americans. For people who are incarcerated, this can mean carrying unwanted pregnancies to term within prison walls and without adequate medical care, giving birth in shackles or solitary confinement, and being separated from their newborn children. For indigenous women, the Hyde Amendment represents just one of many violations of their bodily autonomy. Many Native health clinics delay care due to understaffing, fail to provide emergency contraceptives, and, until recently, did not reliably offer birth control.

This is particularly concerning given that Native women are the most likely to experience rape of any ethnic group. While the Hyde Amendment does now carve out exceptions for rape (as well as incest) on paper, actually obtaining funding in these circumstances is a

FALL 2022 | ISSUE 01 18 UNITED STATES

“Together, these facts illustrate a harrowing reality: Black women are disproportionately likely to seek access to abortion care, disproportionately likely to be denied such access, and disproportionately likely to suffer the consequences of those denials.”

different story. The amendment’s narrow criteria for exceptions create bureaucratic hoops for patients and providers to jump through. An analysis published in the American Journal of Public Health conservatively estimates that, of 1,165 abortions that “qualified for federal Medicaid funding in the year before the interview, 736 were not reimbursed.”

Like Native women, women in the armed forces are also disproportionately harmed by these bureaucratic obstacles. In fact, almost a quarter of servicewomen are survivors of sexual assault. That women who sacrifice their bodies for their country are denied the right to bodily autonomy by the very nation they serve is a disgrace.

By funding abortions for those who want them, states could take a step toward resolving these injustices. Moreover, in addition to helping pregnant people in their own states, funding insurance for abortions would also enable blue states to indirectly protect the rights of women in red states by reducing the pressure on abortion funds. This is particularly relevant in the wake of Dobbs as thousands of people must now take time off work, organize childcare, and cross state lines to receive basic medical treatment. These additional expenses, which can reach over $4,000 per person, have further strained already under-resourced abortion funds. In ensuring that their own residents can use government insurance to pay for abortions, liberal states can enable abortion funds to assist more women in anti-abortion states.

The time to act is now. Pro-life advocacy groups have achieved enormous legislative success despite their relatively small base through

the persistent and passionate advocacy of their most zealous supporters. Now, pro-choice groups may be ready to bring the same level of energy. After Dobbs, people across the nation are particularly alert to issues of reproductive justice. A recent Pew poll found that 56 percent of midterm voters currently consider abortion a top voting issue, in comparison to less than 40 percent a decade ago. Moreover, 71 percent of registered Democrats now say abortion rights are very important to their vote, indicating that we are in a potentially time-sensitive moment for the expansion of reproductive rights. With the political wind from Dobbs at their backs, liberal states have a critical opportunity to connect the right to choose in theory with the right to access in practice.

THE SCARS ISSUE 19 19 UNITED STATES

“While the Hyde Amendment does now carve out exceptions for rape (as well as incest) on paper, actually obtaining funding in these circumstances is a different story.”

The Fight for Fairness in Food An Interview with Kiki Louya

Kiki Louya is a chef, entrepreneur, food activist, community partner, and storyteller from Detroit who was recognized by The New York Times as one of “16 Black Chefs Changing Food in America.” To bring her visions of equity for food and farm workers to life, she founded the award-winning food markets Folk and The Farmer’s Hand, as well as Nest Egg Detroit, the nation’s first entirely women-owned hospitality group. She most recently served as the Executive Director of the Restaurant Workers’ Community Foundation (RWCF), which raises and distributes funds to empower workers in public discourse and workplace policies. Louya is currently working on new sustainable food concepts in Detroit.

Hai Ning Ng (HN): The RWCF published a set of draft guidelines for a more equitable restaurant industry. What was the starting point for those guidelines?

Kiki Louya (KL): I think one overarching theme is the idea of respect. Some parts of the restaurant industry have been trying to legitimize restaurant workers as skilled laborers by requiring culinary degrees. But at the same time, workers with culinary degrees might have paid $60,000 for that education, only to be paid less than $10 an hour for their work. Ideas about respect and legitimacy also have to include conversations around access and fair compensation.

That said, we need buy-in from consumers, too. Consumers have to value not just the end product, but

INTERVIEW FALL 2022 | ISSUE 01 20

Interview by Hai Ning Ng ’23

Illustration by Christine Wang ’23

also the people who created that product. If one is willing to pay for an incredible grass-fed steak, they also have to believe that the farmer who raised it deserves a living wage, as does the butcher, the cook who cooked it to temperature, and the server who put it on their plate. We’re not going to be an equitable industry if our customers don’t respect the work we’re doing.

HN: The guidelines also included sections on specific issues such as healthcare and immigrant justice. Could you tell us more about what they entail?

KL: Because restaurant work touches on so many different aspects of our society, I think it holds up a mirror to how we treat others within our communities. First, restaurant work can be very dangerous. You’re working in a very fastpaced environment with knives and high heat, and you’re on your feet for up to 16 hours a day, yet many restaurant workers go without health insurance. The majority of restaurants don’t have any healthcare plans, and if you’re being paid subminimum wages, you can’t afford to elect into health insurance, either. As time wears on, the physical health issues and the stress can really take a toll on one’s mental health. Subsequently, many people turn to substance use just to cope. One thing we’re doing at RWCF to combat this vicious cycle is giving grants to organizations providing free or very low-cost mental health services to restaurant workers across the country.

Second, there are a lot of undocumented immigrants in the restaurant industry. The risk of deportation means that they often feel they cannot speak up for themselves. Additionally, delivery personnel under third-party services like Grubhub and DoorDash are considered contracted workers rather than full-time employees. This means the companies are not on the hook for providing them with benefits and other employee protections. At RWCF, we’re supporting organizations addressing immigrant rights issues. For example, some organizations provide resources in different languages for workers—undocumented or not—to understand what to do if they’re furloughed or if they need rental assistance, mental health services, urgent care services, etc.

HN: How can a restaurant avoid gentrification and instead engage with and support its community?

KL: Restaurateurs and developers in general are looking at real estate in terms of trying to get a great property below market value. But we also have a responsibility to that existing community to include them in the decision-making. Otherwise, we have simply created a spot in their neighborhood that they may not be able to afford to dine in. Considering the community doesn’t have to mean changing the entire menu or concept; it could also mean having specials, having lower-cost menu items, a five-dollar burger night, a loyalty program, a seniors’ program, a neighborhood discount, a pay-what-you-can or pay-itforward system, and so on. There are so many options if we just start thinking outside the traditional restaurant model.

We also have to think critically about the opportunities we’re giving to people in the neighborhood. Are we

offering them employment opportunities? Do we interact with the community at all? If we find that we are not interacting with community members at all, then we can probably come to the conclusion that we are harming them instead.

HN: How can people who live in cities support better food systems?

KL: I think even people who live in urban areas have “access points,” like farmers markets, which are great places for small farmers and makers to sell their products. I’m also seeing more local goods in smaller stores such as mom-and-pop shops, which tend to work with farmers located on the periphery of their cities. Most states do have a good farming community, and once you start going to the farmers market and seeing some familiar faces, you’ll want to see them every single week.

It’s also really great if you can grow your own produce. Even if you don’t have the privilege of having backyard space, you can grow things in pots or windowsill units or even inside your home. This past winter in Michigan, I grew potatoes and kale. Some urban communities have community gardens, and they’re very much worth it if you can get a plot. It becomes a built-in community with people you can learn from and trade with, so that’s always a good thing to look out for if you move into a new neighborhood.

HN: How do your identities and experiences influence your work?

KL: I think being a chef has absolutely brought me closer to my culture and heritage. My dad immigrated here from the Congo, and growing up as a first-generation African American in this country, the things I ate weren’t really understood by my classmates. But as I got older and started working in the food industry, I learned more about how my culture and other cultures influenced America and American cuisine as we know it today, and seeing those linkages made it feel more like a melting pot than I had ever really thought of it as before. My mom’s family is from the American South, and I used to feel shame around Southern food, too, because it was viewed as unhealthy. But now I just see these beautiful culinary traditions in all the things that we do, and I think having these varied perspectives makes me unique.

Besides my heritage, I think growing up in Detroit was definitely a formative experience. Being from Detroit is interesting because we’re like no other city, yet we’re also a mirror image of what has happened in this country in the last century, from the Ford Motor Company and the advent of automobiles to the Civil Rights Movement. Having this background is why I think a lot about people’s histories, how we treat others, and how every little interaction that we have matters.

THE SCARS ISSUE 21

“Consumers have to value not just the end product, but also the people who created that product.”

Edited for length and clarity.

Uprooting Insecurity

by

In 1967, civil rights activist Fannie Lou Hamer purchased 40 acres of land in the Mississippi Delta. This plot was to be the headquarters of Hamer’s Freedom Farm Cooperative (FFC), a community-based agricultural and economic development project in Sunflower County that sought to support and empower poor Black farmers and sharecroppers. The FFC offered a variety of services to its residents, from affordable housing to scholarships for local Black high school students. Although the cooperative started with only 40 acres, at its peak in 1971 the FFC spanned more than 600 acres and was home to a vibrant community.

The FFC dissolved when Hamer died in 1977, but not without leaving an impact. Generations of Black farmers and activists have followed in Hamer’s footsteps. While agricultural spaces have a long history of exploiting Black labor, Hamer’s FFC is just one example of how these spaces can give rise to a resistance that centers Black farmers, who have long been unsung advocates for food justice and food sovereignty. Hamer saw self-sufficiency as a tool to empower rural Black sharecroppers, tenant

farmers, and domestic workers. Today, activists like Hamer show that self-sufficiency is not only important in the fight against food insecurity, but it is also a key strategy in addressing racial inequality in the United States.

While the United States produces more than enough food to feed everyone in the country, food insecurity in the Black community remains a critical issue. Black Americans are disproportionately impacted by food insecurity as a result of historical inequalities and racial discrimination that continue to this day. Trends in Black farmers’ land ownership provide a striking example of this oppression on a large scale. In 1910, Black farmers owned 17 million acres of land. By 1997, this number dropped to 1.5 million acres, a 90 percent decrease compared to a mere 2 percent drop in white farm acreage over the same period. Even as recently as 2020, Black Americans were 3.2 times more likely to experience food insecurity than white Americans.

Black farming cooperatives and agricultural justice initiatives nationwide are making strides to address these issues, in particular with their efforts to promote food sovereignty. Food sov-

FALL 2022 | ISSUE 01 22 UNITED STATES

Sarah Roberts ’24, a Computer Science and Religious Studies concentrator and a Chief of Staff for BPR

illustrations by Maria Hahne ’24, an Illustration major at RISD

Uplifting Black and marginalized communities by promoting food sovereignty

“Activists like Hamer show that self-sufficiency is not only important in the fight against food insecurity, but it is also a key strategy in addressing racial inequality in the United States.”

ereignty, as defined by the US Food Sovereignty Alliance, is “the right of a people to determine their own policies relative to food and agriculture as opposed to having their food supply subject to market forces.” Organizations like the National Black Food and Justice Alliance (NBFJA), for example, are focused on “developing Black leadership, supporting Black communities, organizing for Black self-determination, and building institutions for Black food sovereignty [and] liberation.” By investing in essential infrastructure to build self-determining food systems and economies, the NBFJA provides Black Americans with the opportunities to create and maintain their own food sources, insulated from white-dominated power structures that contributed to their food insecurity in the first place.

Similar to the NBFJA, Soul Fire Farm was directly inspired by the FFC. Soul Fire Farm is an Afro-Indigenous-centered community farm committed to uprooting racism and seeding sovereignty in the food system. Over 160,000 people participate in the organization’s food sovereignty programs every year, which include

training for Black and brown farmers as well as reparations and land return initiatives for northeast farmers. Soul Fire Farm seeks to reclaim Black and Indigenous peoples’ collective rights to exercise agency in the food system, just like the FFC did. This right has long been denied to Black people. By divorcing their activism from the US food system and promoting self-sufficiency, Soul Fire Farm is able to prioritize the self-determination of Black people.

NBFJA and Soul Fire Farm are just two of the many organizations that demonstrate the power and resiliency of the Black community and the importance of reinforcing their rela-

tionship with the land. These initiatives can be seen as reconceptualized models of the FFC, mirroring many of Hamer’s original goals. With enough resources, they are able to support the self-sufficiency and self-determination of Black communities. This is not only a powerful step in the fight against food insecurity, but also in the struggle for racial equality in the United States. In the words of Leah Penniman, the farm manager and founding co-director at Soul Fire Farm: “If we can have our farms, if we are able to can and preserve for the winter, if we own food hubs and food co-ops as a community, that security becomes the basis for freedom.”

THE SCARS ISSUE 23

“By divorcing their activism from the US food system and promoting self-sufficiency, Soul Fire Farm is able to prioritize the self-determination of Black people.”

SPECIAL FEATURE 26 Borderline Nealie Deol 28 Somalia Syndrome Ian Stettner 30 Overruling Insular Cases Elliot Smith

34 Corrupt Coalition Francisca Saldivar 36 Down Goes Tangier William Forys

Sikhism, 75 years after independence

by Nealie Deol ’24, an Applied Math-Economics concentrator

It may be forever unknown whether a London barrister named Sir Cyril Radcliffe, sketching a map in the summer of 1947, pondered the words written a century earlier by his compatriot: “The pen is mightier than the sword.” Still, the lines Radcliffe drew would in time prove the adage’s validity. On August 15 of the same year, those lines defined the borders of the newly independent nations of Hindu-majority India and Muslim-majority Pakistan, cutting a wound deeper than what could have been produced by the sharpest of blades.

What ensued was the largest migration event in human history. Hindus and Sikhs left the newly formed West and East Pakistan for India, and Muslims left India for Pakistan, with the total number of displaced people estimated at 15 million. Thrown into a state of chaos and confusion, the ruptured border provinces of Punjab and Bengal saw massacres, forced religious conversions, arson, and sexual violence ravage communities that had coexisted peacefully for centuries. While no precise measurement of the death toll exists, between 500,000 and two million people are estimated to have died either while migrating or in the widespread carnage.

For the Sikh population, the wounds of partition stung even more. Whereas Muslims ended up in Pakistan and Hindus in India, demands for an independent Sikh state were brushed aside. That two-thirds of the northwestern province of Punjab—including where the highest proportion of Sikhs lived, and even where Sikhism’s founder, Guru Nanak, was born— became part of West Pakistan only added salt to the wounds. Nevertheless, the scars of decol-

onization shaped a novel Sikh identity rooted in the notion of Punjab as a homeland. In asserting their territorial claims, Sikhs forged a consciousness that underwrote, if not drove, their advocacy for greater autonomy from the Indian central government over the ensuing decades.

Although Punjab formed the geographic backdrop for Sikhism’s origin and much of its evolution, it did not figure centrally into how most Sikhs viewed themselves until partition. Scholar Harjot S. Oberoi traces the transformation of Sikh metacommentaries, or “stories that [a people] tell themselves about themselves,” as a proxy for identity construction across four historical periods: the Guru Phase (1600-1707), the Heroic Phase (1708-1849), the Colonial Phase (1850-1947), and the Nation-State Phase (1948-present). During the first, Sikhs were characterized by their studying Guru Nanak’s and his nine successors’ teachings (bani), founding congregations (sangats), and sharing communal meals (langars). After the last living Guru passed, Sikhs relied on external symbols (the five k’s), a code of discipline (rahit), and scripture (Guru Granth Sahib) to bind the community (Khalsa). The Golden Temple in Amritsar served as a holy pilgrimage destination, but Punjab was still never explicitly linked to Sikh selfhood.

When it became clear in the late colonial period that Punjab might be split, the Sikh political party—the Akali Dal—passed a resolution invoking Punjab as the Sikh “homeland and holy land” and calling for “the creation of a Sikh state.” They justified their petition by professing “intimate bonds of holy shrines, property, language, traditions, and history” to the area, citing the domain of the last Sikh ruler of Punjab, and advocating for the protection of Sikh “religious, cultural, economic, and political rights.” Even though British officials overseeing the transition and non-Sikh independence leaders disregarded

SPECIAL FEATURE | SCARS FALL 2022 | ISSUE 01 26

illustrations by Rosalia Mejia ’23, an Industrial Design major at RISD

their appeals, Sikhs had formally articulated an ideal concept of belonging in the postcolonial paradigm tied to a sense of place in Punjab.

In the post-partition era, Sikh leaders in Punjab continued pushing for territorial rights, now facing an Indian federal government, controlled by the Congress Party, that seemed just as impervious, if not hostile, to their claims. The Indian government opposed carving out an independent religious state, so the Akali Dal agitated for a “Punjabi Suba,” or a state within the republic whose population would be majority Punjabi-speaking. A decade-long campaign resulted in the Punjab Reorganization Act of 1966, which further separated Punjab into a majority Punjabi-speaking (and Sikh) state bearing the same name, a majority Hindu-speaking (and Hindu) state of Haryana, and a union territory called Chandigarh that would serve as the capital city of the two states. Since the Act also specified that Punjab would receive only 23 percent of its river waters, with the rest diverted via canals to Haryana and the state of Rajasthan, the Akali Dal remained profoundly dissatisfied. In 1978, the party re-litigated its grievances by drafting the Anandpur Sahib Resolution, which pressed not only for the redistribution of river waters in Punjab’s favor but, more broadly, for “an autonomous region … wherein the Sikh interests are constitutionally recognized as the fundamental State policy.” The charter, though not secessionist, argued for Punjab gaining total jurisdiction over its administration and law with the central government’s reach limited to matters of foreign policy, defense, currency, railways, and communications.

It is overreach, however, that explained the rise and fall of a more radical brand of Sikh separatism in India throughout the tumultuous 1980s, and the movement’s modern-day vestiges in the Sikh diaspora. The Indian National Congress Party’s errors started with meddling in Punjabi politics, which contributed to the rise of Sikh militancy. In June of 1984, after already suspending the Punjabi state government the year before, Prime Minister Indira Gandhi sent federal troops to raid Sikh militants taking refuge at the Golden Temple in Amritsar, Punjab, which resulted in hundreds of casualties and damage to the shrine. The attack created tremendous ripple effects, beginning with PM Gandhi’s assassination by Sikh bodyguards that in turn spawned anti-Sikh massacres abetted by Congress leaders and the police. Attempts at conciliation with the Sikhs of Punjab gave way to a series of military operations and police action that, by the early 1990s, largely quelled the Sikh struggle.

Nonetheless, the events of 1984 galvanized the Sikh diaspora, which today constitutes the strongest force behind the drive for regional autonomy. Outside of political lobbying and demonstrations, its core campaign has been organizing an unofficial consensus-building referendum among international Sikhs, with an eye toward petitioning the United Nations for an independent state in Punjab on the basis of it being the Sikh historic homeland. The partition of British India into India and Pakistan, excluding Sikh governance, sparked the creation of a new Sikh identity focused on the idea of Punjab as the just place for an autonomous nation. Although unsuccessful to date with respect to their supreme objective, the Sikhs of Punjab persistently advocated for their religious, cultural, linguistic, regional, and territorial rights. Accordingly, they established themselves as a resolute political force that has grown and endured well beyond Punjab’s borders.

THE SCARS ISSUE 27

“While no precise measurement of the death toll exists, between 500,000 and two million people are estimated to have died either while migrating or in the widespread carnage.”

The lasting impacts of America’s raid on Mogadishu

by

by

In 1993, the United States launched a series of raids on Mogadishu, Somalia so disastrous and publicly humiliating that they would redefine presidential decision-making for the next decade. Now, in the wake of America’s exit from Afghanistan, a similar peril looms if we fail to learn from our past.

The year is 1993. Ignited by the killings of 24 Pakistani peacekeepers, the raids on Mogadishu are the culmination of a monthslong UN-backed manhunt for Somali warlord Mohamed Farrah Aidid. As the international community prepares to intervene, they have no knowledge of the warlord’s recent alliance with

a little-known Islamist group operating out of Sudan or the arms and training his soldiers have received from them. Often touted as the group’s major contribution, their coaching instructs the Somali militiamen on the use of rocket-propelled grenades—in particular, to “aim for the tail rotors of US Black Hawks.”