9 minute read

Raise Your Gaze

what do we see on the road? Groundbreaking new research from a docbikes/ bournemouth Uni joint project

interview: Peter henshaw

Advertisement

If you have a mental image of a researcher into neuropsychology, then Shel Smith probably doesn’t fit the bill. She’s a cheerful all-year-round motorcyclist from Dorset who typically rides 20,000 miles a year, a mix of commuting, big tours and track days. Learnt to ride aged four on a Honda Z50R (dad welded on a pair of stabilisers…) and after a few teenage years off-road, took her CBT at 16 and passed her test at 17. At 19, she bought a secondhand BMW K75S for commuting, which she still has, along with an R1100S and R1200GS. “I have a car licence but rarely have a car,” she says. “I use the K75 for commuting and the R1100S was my dream bike as a teenager, really nice. I’ve done a bit of off-road on the GS but really it’s a touring bike.”

Shel trained in developmental and clinical neuropsychology, and was visiting Dorset schools to help kids with autism or Downs syndrome, when she saw an advert for a PhD research project into risk perception among motorcyclists. A joint project between Bournemouth University and DocBike (which came up with the idea and is match funding it), it’s been measuring how riders and drivers perceive risk on the road, measuring eye movements and conducting a series of one to one interviews. “Ian at DocBike started looking at the research and realised there wasn’t much that dealt with this,” says Shel. “There’s been a lot on high-vis clothing, on helmets, some on training, but nothing on targeted collision prevention,” adding that she thinks she clinched the job when she turned up for interview on a bike! “Being a biker has helped massively,” she says. “Other candidates had more education than me but none of them was a motorcyclist, which gives an extra insight.”

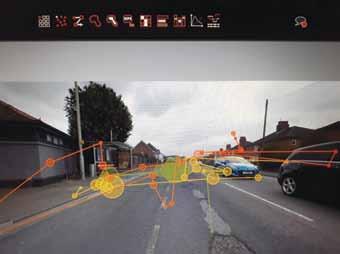

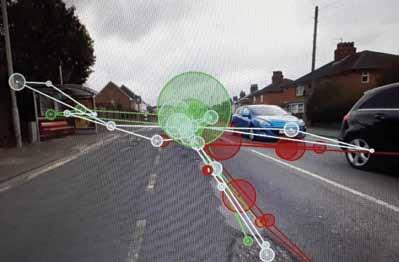

eye tracking machine reveals exactly what you're looking at and for how long. Below: A still from the video volunteers were shown Above: Typical eye tracks from a car driver with a reasonable spread of attention Above right: Motorcyclist is more interested in the pothole Previous page (below left): Researcher Shel Smith is a keen biker

The subjects were all volunteers, with equal numbers of those with advanced training, or who had passed the DVSA test only. “Most of the motorcyclists were older,” said Shel, “with not many under 30, but that’s not necessarily a bad thing, because counter intuitively those most at risk of dying on a bike are males aged 5565 on a 500cc+ machine. All those young food delivery riders you see darting around town, they have plenty of collisions, but are far less likely to die because the speeds are lower.”

eYeS dOwn

These willing volunteers were sat in front of an eye tracking machine, which sends infrared lasers towards the pupil, able to measure precisely what the eye is focusing on. As the subjects watched a video of riding on a typical urban street with plenty of hazards going on, the machine recorded what they were focusing on and crucially for how long. And the results were eye opening (sorry, but I had to).

Compared to drivers, the motorcyclists spent significantly longer looking at certain things, especially dodgy road surfaces and potholes – “the motorcyclist wasn’t just looking at the pothole, they were fixated on it.” Drivers tended to look at more things for less time – while the riders were still looking at a pothole, drivers were noticing the bus stop, cars pulling out of junctions and so on. In the pictures, the circles are what the eye has focused on, and the bigger the circle, the longer it was looked at. The lines between the circles show eye movement between these focuses, what’s known as the saccay. The crucial thing about saccay is that the rider/driver is effectively ‘blind’ while the eye is moving. “The brain shuts the information off for a split second,” says Shel, “which is just to stop you getting dizzy. You think you can still see because the brain overlays a snapshot of the last image you took in, which is called saccadic masking. It’s this which can hide a motorcycle or cyclist. Think of a car driver at a junction, wanting to get out into the traffic, thinking about other things, and quickly scanning the road left to right. Because the scan is so large they’re not seeing a damn thing. What you need to do is to take the time to look. The Government campaign is to look twice, but really it should be to ‘look longer’. That allows the brain to focus on things.” Apparently there’s nothing new about this, and pilots have been taught this ‘look longer’ as a visual strategy for many years, but it sounds like we would all benefit from doing the same.

Another thing which works against car drivers noticing a bike is something called salience bias. Car drivers typically aren’t interested in motorcyclists, though other motorcyclists are. It’s a bit like taking your dog to the park – the dog is only interested in smells, food and other dogs, and won’t really notice anything else. Changing seasons have a similar effect on drivers’ perception of bikers. “In winter,” says Shel, “drivers hardly see any bikes on the road, but then in April they start to come out, but drivers don’t expect them – when things are more familiar, we start to look for them. There are two reasons why motorcycle deaths peak in

April/May – one is that drivers aren’t expecting motorcyclists, and research has established that. The other is that rider skills are rusty – most of them haven’t ridden since the previous October, but think their skills are just as good as when they put the bike away for the winter.”

whY we CRaSh

The one to one interviews with 21 riders and drivers were, if anything, even more revealing than those on eye movements.

Asked what are the top hazards, motorcyclists put road surfaces in the top five every time. And yet it seems that rider perception (fixating on them) of dodgy surfaces is just as likely to cause an accident as actually hitting a pothole. Of the 340 or so motorcycle deaths per year in the UK, surface problems are a contributory factor in about 70 of them, so it’s part of the mix, but not the overwhelming cause.

By contrast, police accident data shows that many accidents happen when riders are in groups – you’re about 70% more likely to have a collision when out with a group of mates. Shel asked the riders whether they ride differently in a group than when solo, and a clear picture emerged. They tended to ride more quickly, but usually just to keep up – meanwhile, they’re having to keep an eye on the riders closest to them as well as the guy out in front. “The brain has the capacity to process about seven items at a time, but group riders can have three times that going on, whether it’s beautiful scenery, tricky corners or higher speeds than riders are used to,” says Smith.

So what can we do? Knowing your route beforehand is a good idea, especially if riding in a group, and as Tail End Charlie is the most difficult position to ride in, it makes sense to put the most experienced rider at the back.

TRaininG iS keY

But rider training is at the core of this research project, with some concrete recommendations going forward to the DVSA. “Roadcraft covers the visual aspect to a certain extent,” says Shel, “but the DVSA rider training manual doesn’t. The DVSA manual has two pages on rearward observation, but none on strategic forward observation. It’s an implicit skill, so it’s sort of assumed by DVSA that novice riders have it.” She adds that there are certain things you can do, such as being in the right position on the road and getting into it when a driver can see you. It’s this extra movement (moving out to the white line before passing a junction for example) that drivers notice. “It’s an evolutionary thing – we’ve evolved to notice sudden movements, which for a lion means food or if it’s for a small animal, means danger. In a field of vision, we only focus on about 5% of what we can see – the other 95% is this rather blurry peripheral vision, but any movement within that will focus our attention onto it.” Interestingly, research indicates that this sort of training would have more beneficial effect than wearing high-vis, with previous studies showing that bright colours have little effect on whether you will be noticed – saccadic masking, not to mention a door pillar, tree or another car, can hide a bike, even when the rider is cloaked in high-vis. Extra lights can make a difference, especially a pair of day running lights arranged so that there’s a triangular formation, which allows the brain to process the speed of an object, but drivers still need to see and register the bike in the first place.

And the key advice for motorcyclists? Look high, raise your gaze, whatever you want to call it, but look ahead, not just at the road immediately in front of you. “We want to change the DVSA training to take account of this. Novice riders tend to focus on what’s immediately in front of them, but we need to look ahead at what’s coming. Balance is also better if you look up and forward.

“We’d like to see all these findings applied to DVSA training,” says Shel. “It doesn’t take an advanced rider to do this – it just needs a couple of pages devoted to forward observation in the DVSA manual and in lessons while training. There has only been one other study on this (in the US) and it was found that after this training was applied to novices, their gaze did go up and forward. While we’re at it, I’d like to have a couple of pages in the DVSA manual about group riding – let’s face it, motorcyclists are social beasts and the vast majority of riding is social.”

The good news is that Shel has spoken to the Chief Examiner of DVSA who has said he is open to these changes, but wants to see the evidence. That should come when this research project is finished early next year. “We’re quietly confident,” says Shel Smith, “that this will happen. We don’t want to beat people with this data; we want to work with them, equipping riders with the training they need to avoid problems.”