The Brigantes Orchestra about us

The Brigantes (Bri-gan-tez) were a collection of Celtic tribes ruled by Queen Cartimandua in 1st-Century Northern England, populating what is now Yorkshire. Literally meaning “high ones”, Brigantes could refer to nobility or to highlanders living on the Pennines or in Hillforts. The Brigantes were tribal and cultured, enjoying theatre and music.

The name Brigantes was chosen for a new orchestra because it encapsulates location, culture and unity: the idea that an ensemble is, roughly speaking, a tribe of musicians.

The Brigantes Orchestra was formed in Sheffield in 2019 in response to the observation that Sheffield did not have a professional symphony orchestra of its own, despite a wealth of local talent. The Brigantes aim to bring high quality orchestral music to the city and surrounding areas as well as to engage new audiences who would not otherwise visit the classical concert hall. This includes a growing population of young musicians in Sheffield schools who are learning a musical instrument and are ably supported and encouraged by Sheffield’s Music Hub and in the Sheffield Music Academy.

Friends of The Brigantes

The Brigantes are currently searching for volunteers for various jobs, including fundraising, flyer circulation and front-of-house at our concerts. This will help to secure the orchestra’s future.

To express your interest, please contact us by email: contact@thebrigantes.uk

Programme 26 February 2022, 7.30pm

The Brigantes Orchestra

David Milsom leader

David Watkin-Holmes tenor

Naomi Atherton horn

Quentin Clare conductor

FELIX MENDELSSOHN (1809 to 1847)

Overture, Op. 21

“A Midsummer Night’s Dream” (1826)

Allegro di molto

BENJAMIN BRITTEN (1913 to 1976)

Serenade for Tenor, Horn and Strings (1943)

I Prologue: Andante

II Pastoral (Cotton): Lento

III Nocturne (Tennyson): Maestoso

IV Elegy (Blake): Andante appassionato

V Dirge (Anonymous): Alla marcia grave

VI Hymn (Jonson): Presto e leggiero

VII Sonnet (Keats): Adagio

VIII Epilogue: Andante

INTERVAL c.2010hrs

JOHANNES BRAHMS (1833 to 1897)

Symphony No. 2 in D, Op. 73 (1877)

I Allegro non troppo

II Adagio non troppo

III Allegretto grazioso (Quasi andantino)

IV Allegro con spirito

FINISH c.2115hrs

You would be welcome to join us for a drink after the concert with a chance to chat to some of the musicians at:

All Bar One, 13 to 15 Leopold Street, S1 2GY 53.3817573, -1.4710059

///verge.live.dangerously(!)

Programme notes “...that yet we sleep, we dream...”

Felix Mendelssohn - Overture, A Midsummer Night’s Dream

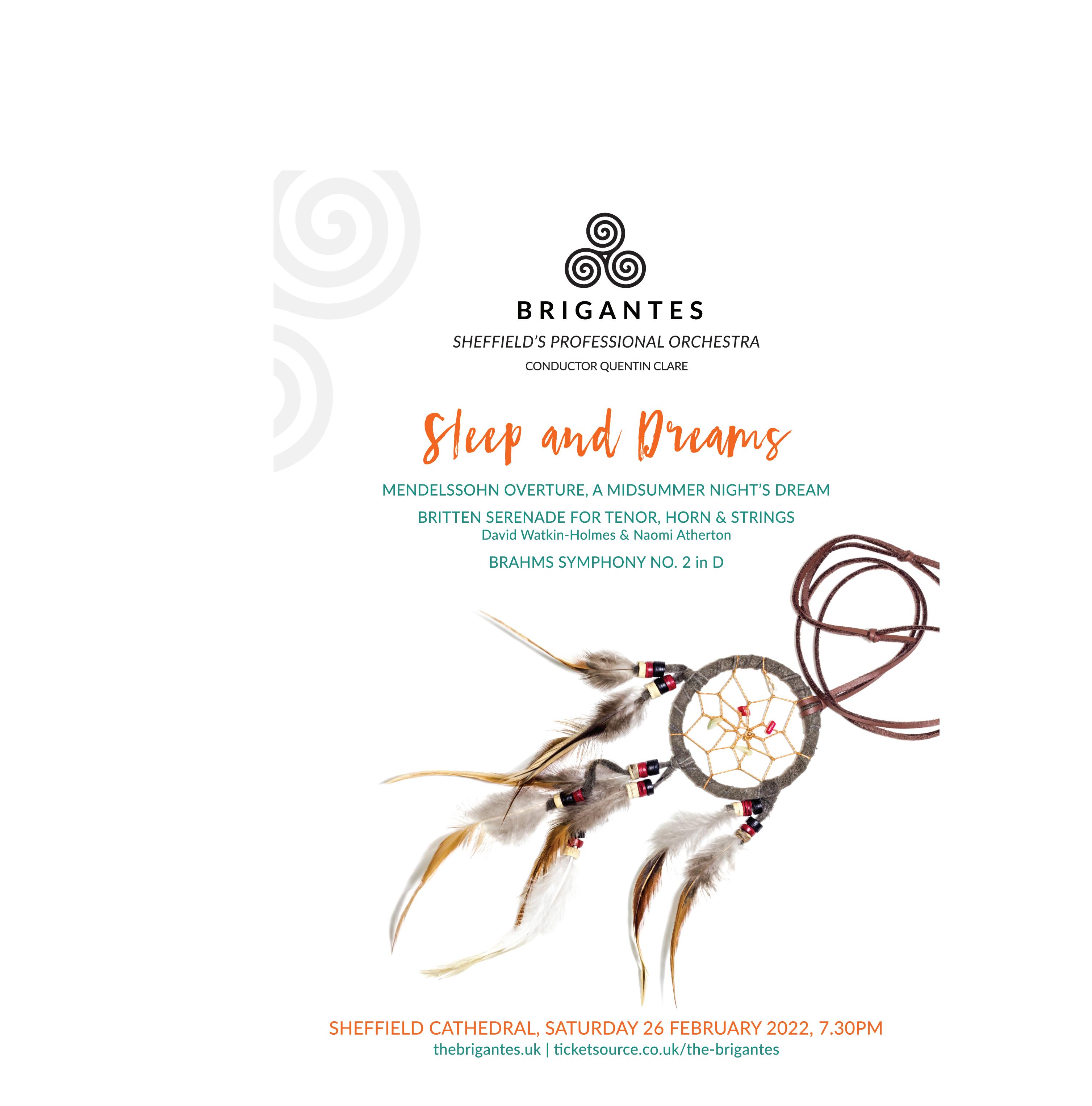

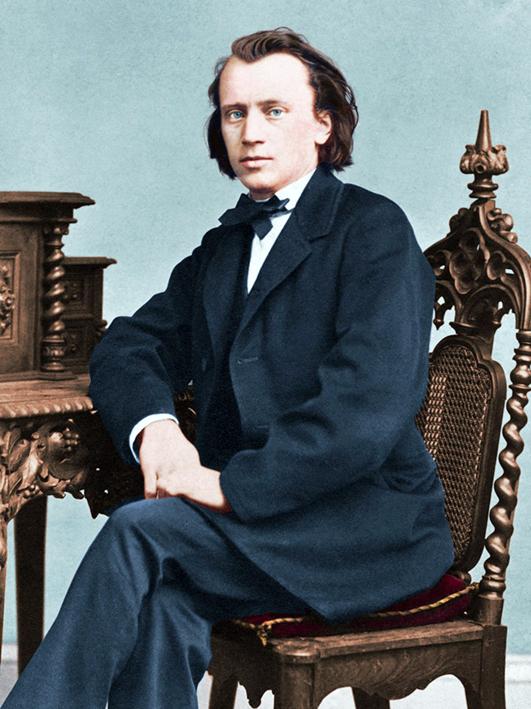

Felix Mendelssohn Bartholdy by James Warren Childe c.1830

Felix Mendelssohn Bartholdy by James Warren Childe c.1830

There are many adaptations of Shakespeare’s work which take it from the theatre or page to the salon, concert hall or opera house. From Purcell to Bernstein ( Romeo and Juliet or West-Side Story ), and Salieri to Verdi ( Falstaff , Macbeth and Othello ). Berlioz ( Much Ado about Nothing or Beatrice and Benedict ), Elgar ( Falstaff ), Prokofiev ( Romeo and Juliet ), Sibelius, Honegger and Adés ( The Tempest ), and Britten ( A Midsummer Night’s Dream ) are notable in a long list. Joachim Raff attempted to distil Macbeth , The Tempest and Romeo and Juliet into concert overtures, to somehow capture everything important to the story as well as the atmosphere of the play in music of only ten minutes. Tchaikovsky’s Fantasy

Overture, Romeo and Juliet is better than most at capturing the psychology of a stage drama. It was still a work of hard-won genius; revised through multiple versions, it was declared flawed early in its inception, but has such strong thematic material that it has survived into the modern repertoire.

For the seventeen year old Mendelssohn to emphatically set the standard for this sort of endeavour is remarkable. He composed the concert overture to A Midsummer Night’s Dream quickly and easily in the summer of 1826, having read a German translation of the play a few months earlier. The music is mature and assured and not only captures and clearly describes the disparate elements of the story, but does so with a modern and original ear for the orchestration. Even in itself, the form is an innovation. Rather than the overture to a stage work, the music is conceived as the prelude to a concert programme: a short opening burst to set the scene, enliven the audience, and warm up the orchestra. However, although the overture is programmatic and the orchestration advanced, - essential elements of a new “romantic” style, the music is rooted in the classical tradition, with even phrase lengths, sonata form, and an instrumentation of almost Mozartian proportions.

Later, other concert overtures like The Fair Melusine , Ruy Blas and The Hebrides would be a model evolving into the late romantic tone poems of Franz Liszt and Richard Strauss.

1760 George

Programme notes “...you have but slumbered here...”

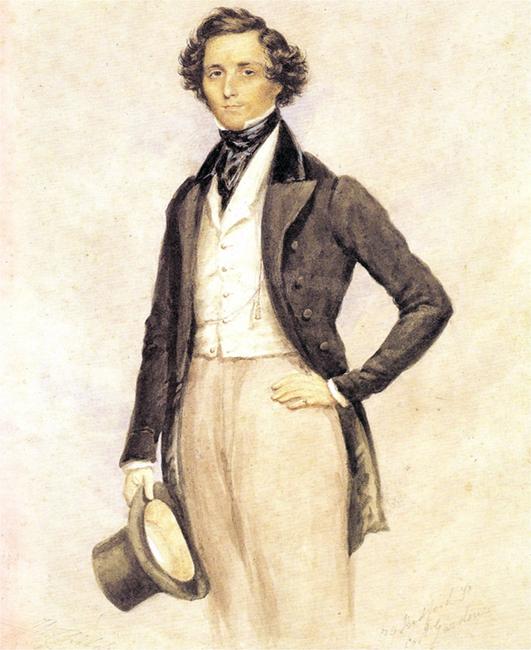

Second Folio of 1632

The book opens: “Once upon a time”. Four delicate, airy chords played by the woodwinds set the scene in E major. We are transported suddenly into the minor key, otherworldly, in the magic wood as the violins scamper and dance like fairy wings or the leaves of the trees rustling. Royal, majestic music erupts from the chittering, in bright E major. This is the real world of the duke’s court and the royal lovers. The lover’s music, sensuous and lyrical follows, and this is eventually entwined with Bottom’s braying ass (we shouldn’t forget that Titania too falls in love). Mendelssohn explores the darkness of the magic wood during the development section. The fluttering violins return, this time with violas and cellos to take us deeper into the gloom. The music is layered with distant horn calls as the duke hunts, faraway trumpet fanfares from the city of Athens, and other noises of things unseen amongst the trees.

Puck, the mischievous sprite is there playing tricks with the lovers using a magic love potion. At his master’s instigation he even uses it on his mistress Titania, Queen of the Fairies. The “rude mechanicals” rehearse their play deep in the wood, ignorant of the magic around them.

The lover’s music returns, muted in more gentle colours, no longer always agitated, but gradually losing its energy as dawn beckons. Bottom can still be heard braying.

Mendelssohn does not explore Shakespeare’s resolutions, only the characters, their surroundings, and their motivations. After the fairy world returns with a final flutter, they take on the lover’s music and transform it into their minor key. It gradually disintegrates into fragments, and the woodwind chords return to herald the dawn and gently close the book.

If we shadows have offended, Think but this, and all is mended-That you have but slumbered here

While these visions did appear. And this weak and idle theme, No more yielding but a dream...

1764 Spinning Jenny

1776

1788

1804

1800

Programme notes “...o soothest sleep!”

Benjamin Britten - Serenade for Tenor, Horn and Strings

“The subject is Night and its prestigia (conjuring tricks): the lengthening shadow, the distant bugle at sunset, the Baroque panoply of the starry sky, the heavy angels of sleep; but also the cloak of evil—the worm in the heart of the rose, the sense of sin in the heart of man. The whole sequence forms an Elegy or Nocturnal (as Donne would have called it), resuming the thoughts and images suitable to evening.” wrote Edward Sackville-West, the dedicatee of the Serenade .

Like Mendelssohn, Britten was prodigious in his youth and the Serenade afforded him no great struggle to create. He described the work as “of no real importance, but pleasant enough.” However, the work has endured, not just for its often powerful and moving content, but also

as it constitutes a major work in the repertory showcasing the French horn. Indeed, the solo horn begins and ends the work alone. Britten directs the player to use the instrument in its natural state without pressing any of the keys, much like the earlier versions of the horn in the baroque and classical periods. In this way, the tuning sounds antique, like a military bugle playing the Last Post.

The Serenade is also something of a test piece. Undoubtedly, at around the same time as he worked on it, Britten was already engaged in the composition of his first great opera, Peter Grimes . This was to be the forging of the musical relationship with his life-partner Peter Pears. In the Serenade , all the elements of the vocal writing for Grimes are laid out for exploration. Britten surveys the facets of Pears voice, its range, colour, those areas of the instrument which were strongest or easiest for him, the tessitura where the expression of the text was optimal, and even a test of the dynamic possibilities: at the height of the Dirge , when the onslaught of fortissimo strings and the full volume of the horn threaten to overwhelm, the voice cuts through it all.

The songs in the Serenade vary the relationship between the voice and horn. The last song, Sonnet , is completely without the horn in order to give the musician time to leave and play the epilogue off-stage. This is not only a

1826

1855

Benjamin Britten c.1950Programme notes “...o soothest sleep!”

logistical conceit: the text of Keats’ poem, “O soft embalmer of the still midnight,” is about the ultimate sleep, of death: “forgetfulness divine.” Whilst it is lonely and desolate music, it also glows with transfiguration and warmth. At the funeral of Dennis Brain, for whom the solo horn part was written, it was this song, where the horn is silent, that was given in memoriam.

Nocturne banishes the horn to rustling cadenzas between stanzas, the refrain, “blow bugle, blow” suggesting again a military link where the horn imitates the distant bugle. The tenor dominates the main stanzas of the poem, describing the glorious scene at sunset, “the long light shakes across the lakes.” The song also draws together the end of the day with our spiritual release: “Our echoes roll from soul to soul, And grow forever and forever.”

In Elegy , the lines for the tenor voice, “O rose, thou art sick” reverse the structure of Nocturne and the horn plays elegiac lines alone with the strings. Confined to a short, still moment in the centre of this turbulence, the eye of the storm perhaps, Blake rather enigmatically hints at the destruction of innocent love by the sexual act. Possibly “his dark secret love” had added connotation for Britten and Pears. The horn wails in grief at the close of the song. Immediately, the tenor mimics it at the beginning of the next song, Dirge , “This ae night, this ae night...”.

Dirge describes in terrifying language the night after death, before burial the following day, where one’s acts of charity in life might pave the way to a better afterlife. The construction of this song is most ingenious. Britten keeps the vocal part simple, a repeated, almost sing-song incantation redolent of a children’s rhyme, “Ring-a-ring o’ roses” springs to mind. The accompaniment is dark and insistent. It is a beat or two longer in phrase length than the catch tune, and so it never settles on the first beat of the bar until the horn emphatically enters transforming the accompaniment into a melody. The combined forces threaten to overwhelm the vocal part in descriptions of the fires of purgatory and the bridge (or ‘Brig’) of dread.

Only Pastoral and Hymn are relatively simple in their combining of the two soloists. One is a summer pastoral picture of dusk, which describes how the long light distorts the shadows. The other, Hymn , is almost Mozartian in its light, elegant writing and is an eloquent homage to the moon. In both cases, when the night is just the night, without terror or the implication of the ultimate sleep, the two instruments create dialogue and are musically symbiotic - one extolling the virtues of the other.

1865 Wagner Tristan and Isolde

1871 Middlemarch

1877

1884

1902 Mahler

1900 romantic period

20th/21st century

Programme notes “...lead the world the way to rest.”

Charles

Cotton

(1630 to 1687) - Pastoral: from The Evening Quatrains

The day's grown old, the fainting Sun

Has but a little way to run, And yet his steeds, with all his skill, Scarce lug the chariot down the hill.

The shadows now so long do grow, That brambles like tall cedars show, Mole-hills seem mountains, and the ant Appears a monstrous elephant.

A very little little flock

Shades thrice the ground that it would stock; Whilst the small stripling following them Appears a mighty Polypheme.

And now on benches all are sat

In the cool air to sit and chat, Till Phoebus, dipping in the West, Shall lead the World the way to rest.

Alfred, Lord Tennyson (1809 to 1892) - Nocturne: The Princess

The splendour falls on castle walls

And snowy summits old in story:

The long light shakes across the lakes,

And the wild cataract leaps in glory.

Blow, bugle, blow, set the wild echoes flying, Blow, bugle; answer, echoes, dying, dying, dying.

O hark, O hear! how thin and clear, And thinner, clearer, farther going!

O sweet and far from cliff and scar

The horns of Elfland faintly blowing! Blow, let us hear the purple glens replying: Blow, bugle; answer, echoes, dying, dying, dying.

O love, they die in yon rich sky, They faint on hill or field or river: Our echoes roll from soul to soul, And grow forever and forever.

Blow, bugle, blow, set the wild echoes flying, And answer, echoes, answer, dying, dying, dying.

William Blake (1757 to 1827) - Elegy: The Sick Rose

O Rose thou art sick.

The invisible worm, That flies in the night

In the howling storm:

Has found out thy bed

Of crimson joy: And his dark secret love Does thy life destroy.

Programme notes “...enshaded

in forgetfulness divine...”

Anonymous (14th Century) - Dirge: The Lyke-Wake Dirge

This ae nighte, this ae nighte, (Refrain:) Every nighte and alle, Fire and fleet and candle-lighte, (Refrain:) And Christe receive thy saule.

When thou from hence away art past, To Whinny-muir thou com'st at last;

If ever thou gavest hosen and shoon, Sit thee down and put them on;

If hosen and shoon thou ne'er gav'st nane

The whinnes shall prick thee to the bare bane;

From Whinny-muir when thou may'st pass, To Brig o' Dread thou com'st at last;

From Brig o' Dread when thou may'st pass, To Purgatory fire thou com'st at last;

If ever thou gavest meat or drink, The fire shall never make thee shrink;

Ben Jonson (1572 to 1637) - Hymn: Cynthia’s Revels

Queen and huntress, chaste and fair, Now the sun is laid to sleep, Seated in thy silver chair

State in wonted manner keep: Hesperus entreats thy light, Goddess excellently bright.

Earth, let not thy envious shade

Dare itself to interpose; Cynthia's shining orb was made

Heaven to clear when day did close: Bless us then with wished sight, Goddess excellently bright.

John

Lay thy bow of pearl apart

And thy crystal-shining quiver; Give unto the flying hart

Space to breathe, how short soever: Thou that mak'st a day of night, Goddess excellently bright.

Keats (1795 to 1821) - Sonnet: To Sleep

O soft embalmer of the still midnight, Shutting, with careful fingers and benign, Our gloom-pleas'd eyes, embower'd from the light, Enshaded in forgetfulness divine:

O soothest Sleep!

if so it please thee, close In midst of this thine hymn my willing eyes,

Or wait the "Amen," ere thy poppy throws

Around my bed its lulling charities.

Then save me, or the passed day will shine Upon my pillow, breeding many woes,— Save me from curious Conscience, that still lords Its strength for darkness, burrowing like a mole;

Turn the key deftly in the oiled wards, And seal the hushed Casket of my Soul.

The second symphony by Brahms feels rather unrestrained, open, and free. This should not be a surprise to us. His first symphony was something like twenty-one years in the making from early sketches to premiere, and underwent so many transformations that much of the material ended up in other compositions like the first piano concerto. “You can’t have any idea what it’s like to hear such a giant as Beethoven marching behind you,” he wrote in 1872.

He tested the water and practised his craft with works like the two Serenades, the Haydn Variations , the first Piano Concerto, as well as choral works with orchestra like the Alto Rhapsody and Schicksalslied . Even his chamber music was symphonic in stature - compositions

like the first piano quartet, which Arnold Schoenberg later realised would be prime material for orchestration itself, and the first published string quartets. We can only guess at the potential in the twenty or so other quartets Brahms wrote before these, but later destroyed. Whether the first symphony became a block because the thematic material he felt he ought to use was unyielding and difficult, or whether he genuinely lacked the confidence to finish the work with Beethoven’s ninth as a monumental forebear, we will never know. However, once that hurdle was overcome and the symphony performed, the ease with which the second symphony arrived in only a few months over the summer of 1877 must contribute to its feeling of ease. The dam had burst and a slew of other symphonic works like the Violin Concerto, the two concert overtures, and the second Piano Concerto quickly followed.

Brahms teased his audiences expectations of the sort of work which might follow his titanic first symphony. “It is so melancholy that you will not be able to bear it. I have never written anything so sad, and the score must come out in mourning," he wrote to his publishers in November of 1877. Their delight when finally they heard what is essentially a pastoral, idyllic work was plain. However, the symphony does have a darker undercurrent. Indeed, the famous Wiegenlied (cradle song) borrowed for the second subject of the opening movement is in the minor key and rests temporarily in such gloom and with ominous feeling that one cannot find it restful or lulling. Similarly, the orchestral colour is often dark and portentous; lugubrious trombone chorales, passages for the low strings and clarinets, as well as a lone timpani, mark the introduction of the first movement. Although sunshine does inhabit the symphony and no more joyous ending to a work could be imagined, like Mendelssohn in his overture and Britten in his Serenade, the dark is not always an empty, serene place.

Programme notes ...you will wake once again.”

The symphony begins with a three-note motif in the cellos and basses, a kind of satisfied sigh, before two horns set a scene of mountain glens and pastoral idyll. The violins, and in particular the second violins, as Brahms frequently does in other works, are instruments held back from the texture for nearly a minute so as to frame their lyrical beauty when finally they arrive to ripen the orchestration. The second subject, played initially by the violas and cellos, is the famous Wiegenlied , which he had set in 1868, though here with a feeling of nostalgia and in that dark, minor key. The first movement moves through many landscapes, from intimate pastoral settings to towering, mountainous symphonic textures which employ the brass instruments and particularly the added bass sound of the tuba. A solo horn draws the movement into its peroration, sitting on cushions of lush string harmonies. The strings surrender their bowed sound to pizzicato and the winds close the movement in a nod to Brahms’ earlier Serenades.

The second movement begins in a lyrical outpouring from the cellos, which Brahms draws out to exquisite length. The single theme lasts for more than a minute and traces a path through accompaniments of various hue, from grumbling bassoons to placid, warm brass and flutes, before eventually emerging into the light when the violins take up the melody. The winds play the theme in its evolution, again taking up the textures of a serenade, before a stormy interlude intervenes. Calm is restored, but it is an uneasy rest, the melody irrevocably altered by the torrent.

The sound of a wind serenade returns: a solo oboe opens the third movement. Like the first symphony, Brahms dispenses with the dance or scherzo-like movements of Beethoven and Haydn, and gives us something approaching an intermezzo. It is not without the wit of a scherzo or the feeling of dance, but it is altogether more gentle. Short bursts of energy always give way to the gentle serenade.

The finale whispers itself into life. The melody is once again drawn-out, but unlike the opening to the second movement, it is pent up and dares not draw breath. Like Haydn in his Miracle Symphony, number 96, it teases the audience, who feel the imminent explosion, but cannot guess where it will come. When it does, it is removed from the strong main beat of the bar and feels like it stumbles onto the stage. The last movement is joyous and stays routed in the home key of D Major for much of its duration. It dances with energy, almost to make up for the third movement’s passivity. Except for a broader, more lyrical second subject, it maintains this energy to the end. A short, rather cosmic moment in the central part of the movement with ethereal strings and portentous-sounding trombones leads back to a reprise of the opening hush. With recapitulations of the main themes, Brahms heads home, gradually raising the energy and volume until the three trombones are left exclaiming the home key in burnished tones, surrounded by the solid pillars of the final chords.

Programme notes in sleep and dreams

Titania

by Edwin Landseer c.1849

Titania

by Edwin Landseer c.1849

“The eye of man hath not heard, the ear of man hath not seen, man's hand is not able to taste, his tongue to conceive, nor his heart to report what my dream was.” Thus speaks Bottom in Act Four of A Midsummer Night’s Dream , having woken from a “dream” in which he was given the head of an ass and attracted the amorous advances of Titania, the Fairy Queen. As often happens, the most ridiculous character is given a profound understanding beyond the wit of the intelligent characters: Bottom sums up the intangible nature of dreams.

The world of sleep and dreams has been fertile territory for artists through the ages. It has provided a door into escapism and fantasy

in Alice in Wonderland ; revealed our inner thoughts and fears, a frightening prospect for Winston in 1984 ; contained unfathomable horrors in A Nightmare on Elm Street ; been an agent for repentance and expiation for Scrooge; and a conduit for God’s plans, as interpreted by Daniel and Joseph. Dreams have also been a ‘Deus ex machina’ for lazy or unimaginative writers: who can recall their disillusionment on learning that the death of Bobby Ewing in Dallas was merely a dream? In music, Berlioz’ Symphonie Fantastique conjured opium-induced dreams, Britten’s Serenade was inspired by poems about the night and sleep, and more recently, Aerosmith described watching a lover sleep in I don't want to miss a thing . Music can be soporific, easing the gradual descent into sleep, with Brahms’s Wiegenlied, the lullaby in the first movement of his second symphony, now depreciated into electronic tinkles from garishly-coloured mobiles.

In the modern world, ‘following our dreams’ means reflecting on who we are and how circumstances, or poor confidence, prevent us from achieving our ambitions. An inability to dream is banal, boring, worn out. As Bill Clinton once said, “when our memories outweigh our dreams, it is then that we become old” .

But what is sleep, and can science fully explain its mysteries? In short, “no”. That sleep is important is beyond doubt. From an evolutionary perspective, there is a vulnerability to predators in being unconscious and defenceless that should have been rooted out by natural selection if sleep was indeed unimportant. But many animals do sleep and, in the case of hibernation, for a very long time. In humans, it is estimated we spend around a third of our time either asleep or attempting to do so.

NOTES 12

and BottomProgramme notes in sleep and dreams

It is essential we sleep: genetic conditions, like Fatal Familial Insomnia, make sleep impossible and lead to death within months or years. There are many other disorders of sleep. Narcolepsy, a fundamental part of River Phoenix’s character in Gus van Sant’s My Own Private Idaho , is a condition where the body cannot control the natural rhythms of wakefulness and sleep, leading to sleep at inappropriate times and in strange places. Sleep paralysis is a

frightening condition where someone wakes up, but their body remains paralysed. Ondine’s Curse, named after the novella Undine , later a play by Jean Giraudoux, is a condition in which the brain does not tell the body to breathe during sleep, more recently called Central Hypoventilation Syndrome.

Less severe sleep disorders also cause significant distress – just ask the parents of newborn babies, or shift workers! Poor concentration and attention, impaired memory, irritability, cognitive slowing, paranoia, and phobia all result. Chronic insomnia can lead individuals to seek extraordinary solutions; no matter what your view of Michael Jackson, his use of general anaesthetic at home, usually the preserve of anaesthetists in theatres during major surgical operations, shows the desperate lengths to which insomnia can drive people.

The role of sleep in memory and learning cannot be overstated: Dr Jane Herbert, formerly of the University of Sheffield, showed sleep was essential for learning and memory in toddlers. “Burning the candle at both ends” at revision time can be counterproductive for students, and musicians find sleep can help with the technical facility of a difficult passage of music.

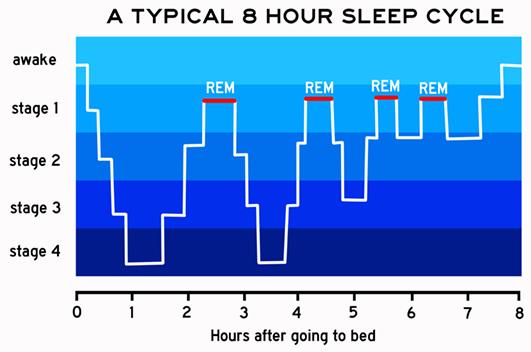

Sleep is not a passive state in which the brain switches off and powers down, like turning the TV or computer off at night. Recordings of electrical activity in the brain, called electroencephalography (EEG), show sleep is an active process requiring significant energy. It can be divided into different states: States 1 to 3 are quiet sleep, and State 4 is Rapid Eye Movement sleep, a term adopted by Michael Stipes and Peter Buck for their rock band REM, during which we enter the fantasy or nightmare realm of dreams. During the night, we progress through these sleep states, cycling through quiet and REM sleep several times, with REM becoming more prominent towards the morning. Cycling through these stages is essential to feeling refreshed: we need good quality, as well as quantity of sleep. Drugs, pain, sleep apnoea, and alcohol are some things that alter sleep cycling and, therefore, its quality.

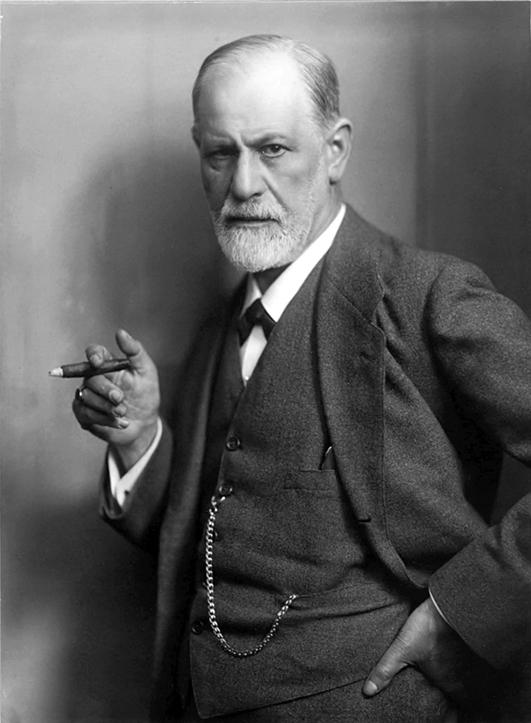

Programme notes in sleep and dreams

But what about dreams? Are they really a portal into our subconscious? This question remains unanswered. Sigmund Freud published ‘The Interpretation of Dreams’ in 1899, in which he claimed that dreams have triggers or anchors in the events of the previous day. Freud was no Daniel or Joseph. His stubborn insistence on applying the Oedipus complex and repressed sexuality to dream interpretation reduced the value of his observations. It is not clear if Freud ever did say “a cigar is sometimes just a cigar”, but the warning not to over-interpret is apposite.

Extensive scientific work will continue into sleep and its disorders. This new knowledge risks reducing its mystique, romance, and

intrigue: imagination lurks in the unknown.

For now, let that creativity run free and enjoy the concert, hopefully without falling asleep before the end!

Dr Anthony Hart Trustee, The Brigantes OrchestraNext Season

Our season 2022 / 2023 will be announced in May. Why not sign up to our mailing list to be one of the first to know what’s in store for next year?

thebrigantes.uk/join-our-mailing-list

A little teaser... expect music by Vaughan Williams and Elgar, Debussy and Suk, a favourite soloist drops in again, and we’ll play something very local by Eric Fenby (don’t forget your hat!).

Musicians performing

The Brigantes are:

Robert Looman

Jennifer Dyson

Rachel Clegg

Dave Benfield

Emily Wilson

Steph Yim

Beth Duncan

Alice Braithwaite

Simon Twigge

Mary Fair

Janus Wadsworth

Tim Page

Murray Greig

Gordon Truman

Anna Marshall

Kyle MacCorquodale

Josh Allen

John Watterson

With thanks to:

David Milsom

Rebecca Smith

Abigail Smith

Dora Chatzigeorgiou

Louise Carey

Emily Chaplais

Elyena Clapperton

Mollie Wrafter

Callum Sherriff

Bianca Blezard

Eleanor Shute

Holly-Rayne Bennett

Rosie Nicholson

Rachael England

Amanda Gillham

Rebecca Howell

Ralph Dawson

Barnaby Adams

Jonathan Kightley

Hazel Parkes

Graham Gillham

Joy Bower

Gemma Wareham

Alisa Lewin

Clara Pascall

Jonny Ingall

John Parsons

Caroline Steer

Aaron Barrera Reyes

Matthew Barks

Gemma Murray

Marcus VinÍcius

de Oliveira

David Watkin-Holmes tenor

Originally from Herefordshire, David sang with the National Youth Choir of Great Britain before studying music performance at the Royal Welsh College of Music & Drama and the Royal Birmingham Conservatoire, where he was awarded the St Clare Barfield Rose Bowl for Operatic Distinction. As a student he also received a scholarship for the Samling Artist Programme with Thomas Allen, became a finalist in the Geraint Evans Memorial Competition and won the Mario Lanza Opera Competition.

Highlights of his career include the premieres of dramatic works by Will Todd and Stephen McNeff with recordings for the Mirasound Klassiek, Naxos Marco Polo and Priory Records labels, and other notable performances for RTÉ Radio with the National Symphony Orchestra of Ireland and Wexford Festival Opera under Maurizio Benini and Vladimir Jurowski, at the Amsterdam Stadsschouwburg and Koninklijke Schouwburg in the Netherlands under Quentin Clare, and with the Royal Philharmonic Orchestra and English National Opera Studio in the UK.

In addition to the Serenade , his repertoire includes such major works as Beethoven's 9th Symphony, the Verdi Requiem and Puccini Messa di Gloria , and Elgar's The Dream of Gerontius , together with roles encompassing Alfredo La traviata , Ishmael Nabucco , Don José Carmen , Prince Rusalka , Rodolfo La bohème and Cavaradossi Tosca .

A passionate educator, David is also a fellow of the Higher Education Academy and a visiting senior lecturer in voice at the Leeds Conservatoire.

Naomi Atherton horn

Born in Bradford, West Yorkshire, Naomi took up the horn at the age of eight. She went on to study at the Royal Northern College of Music with Michael Purton and Derek Taylor. Whilst in her first year at college she won the brass final of the BBC Young Musician of the Year.

Highlights of her solo career have been concerti with the BBC Philharmonic, Manchester Camerata with Douglas Boyd, and the Ulster Orchestra, as well as recitals around the country and regular broadcasts on BBC Radio 3.

Naomi is a member of the Sheffield-based chamber group Ensemble 360. She has been principal horn of Manchester Camerata and the Northern Chamber Orchestra for many years, but has also appeared as guest principal with such groups as the Goldberg Ensemble, Royal Liverpool Philharmonic, English Northern Philharmonia, Royal Northern Sinfonia and Scottish Chamber Orchestra. She has appeared at many festivals including in Edinburgh, Cheltenham, Bath and at the BBC Proms.

Naomi lives in the Peak District and in her spare time like to run in the hills, cook, and look after her chickens and flock of Ryeland sheep.

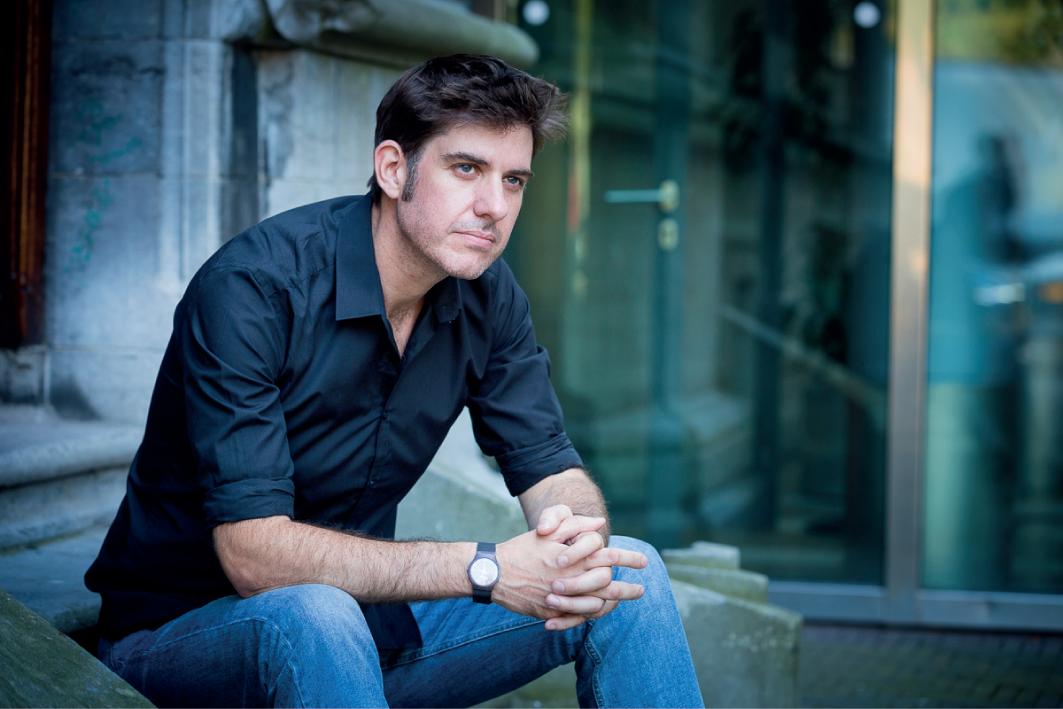

Quentin Clare conductor

The British conductor Quentin Clare made his professional debut at the age of just 25 when he conducted the Hallé Orchestra in the prestigious Bridgewater Hall Manchester. Since then, he has worked with many orchestras in the UK including the BBC Philharmonic, Royal Northern Sinfonia, Orchestra of Opera North and Ensemble 11, as well as having performances broadcast on British and European television and radio.

Quentin’s international career has seen him conduct orchestras in Europe such as the Danish National Symphony, Dutch Radio Philharmonic, Symphony Orchestra of Nancy and the Nürnburg, Würzburg, Hagen and Bochum Symphony Orchestras. He is equally experienced in the opera house working in France, The Netherlands and in Germany on productions including Stravinsky's The Rake’s Progress , Britten’s A Midsummer Night's Dream and in particular the French premiere of Robert Carsen’s acclaimed production of Richard III by Giorgio Battistelli.

Much in demand as an inspirational conductor of young musicians, he has worked at the conservatories in Ghent, Birmingham, Durham, Den Haag, Tilburg and Weimar, as well as holding posts with the university orchestras of Nijmegen and Leiden. Quentin has been principal guest conductor with Young Sinfonia in Newcastle and is music director of The New Mannheim Orchestra, and Pulcinella. He directed with great success the 2014 tour of the National Student Chamber Orchestra of the Netherlands (NESKO) and the 2015 tour of the National Student Symphony Orchestra of the Netherlands (NSO), and in doing so became the first British conductor to work with both of these ensembles.

registered charity: 1187752

This concert has been generously supported by Neuronatal Ltd