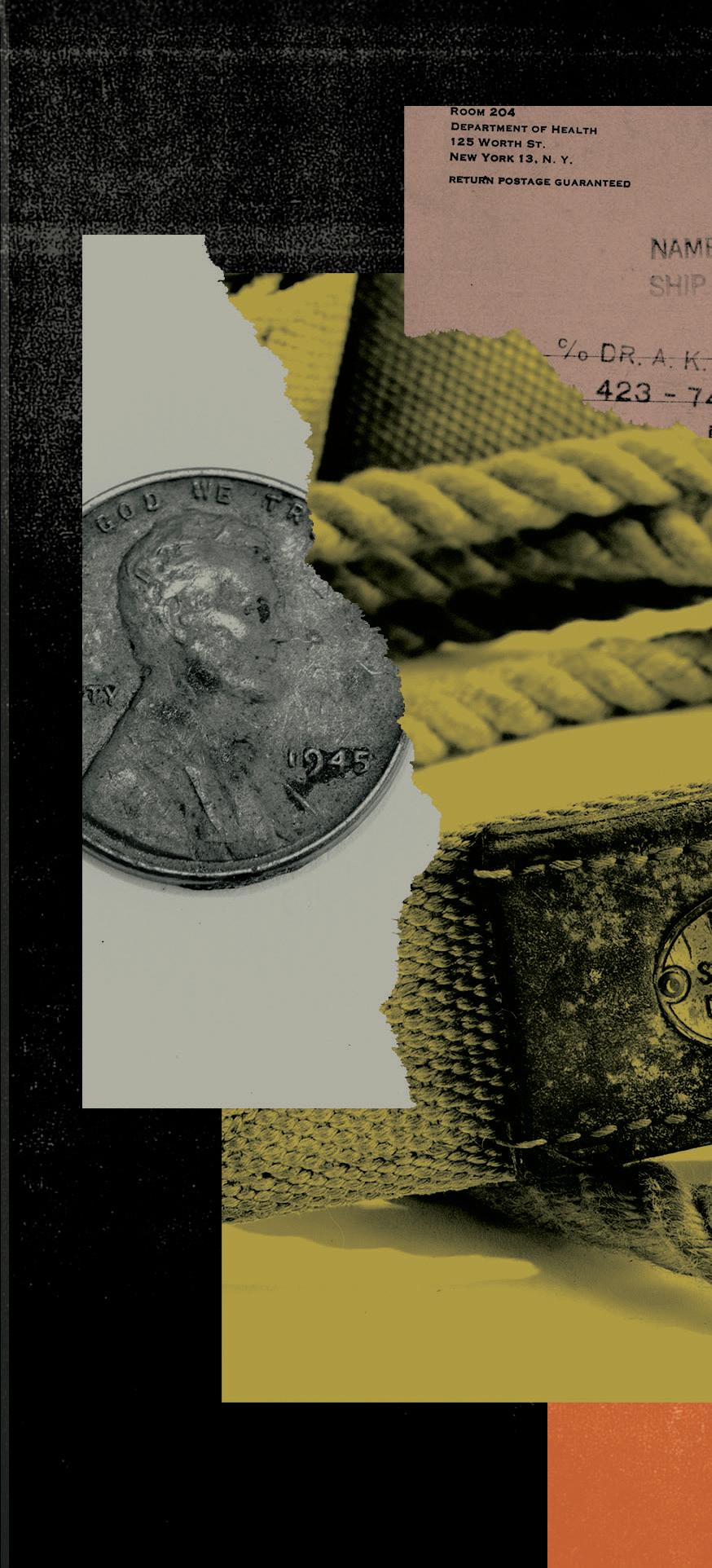

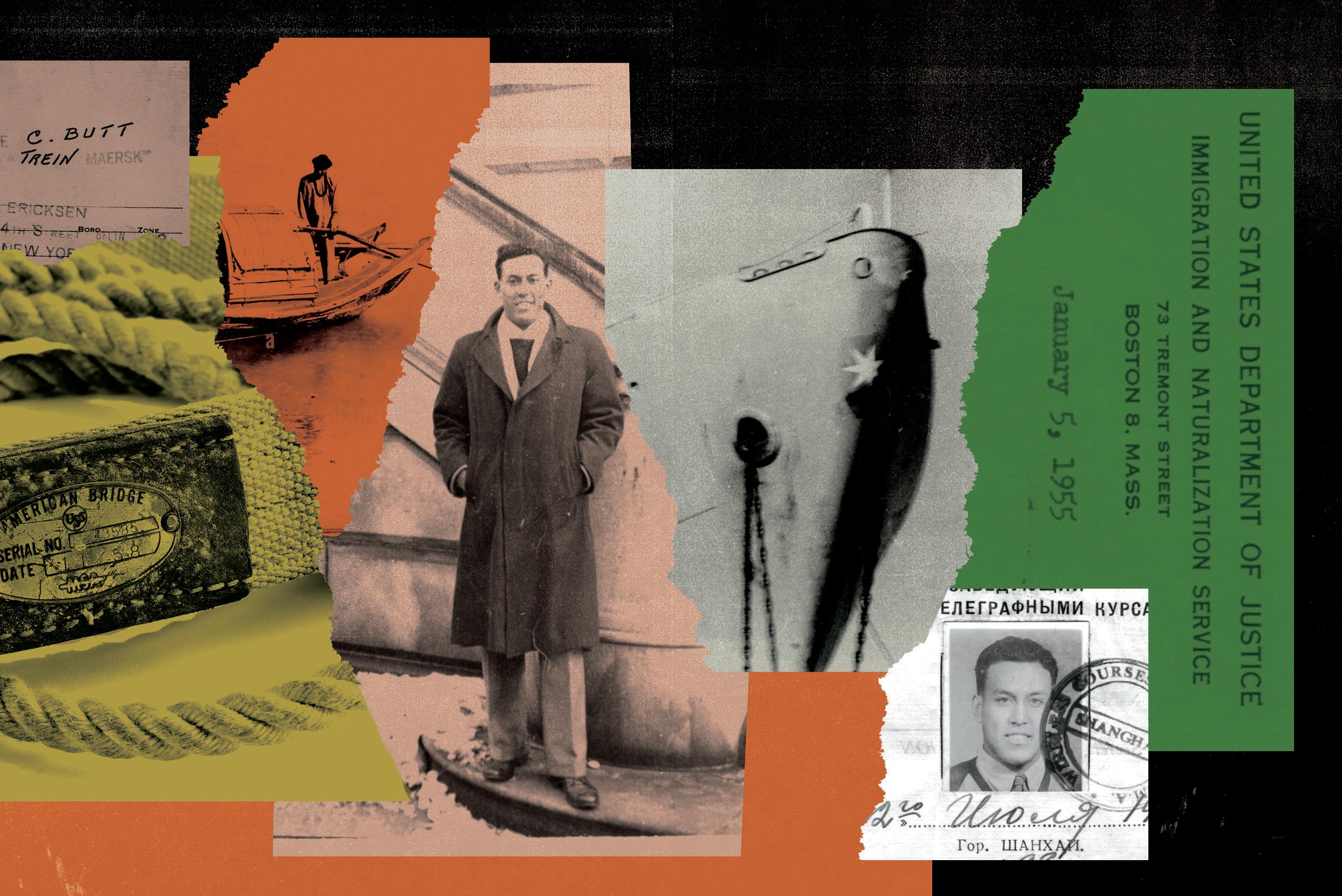

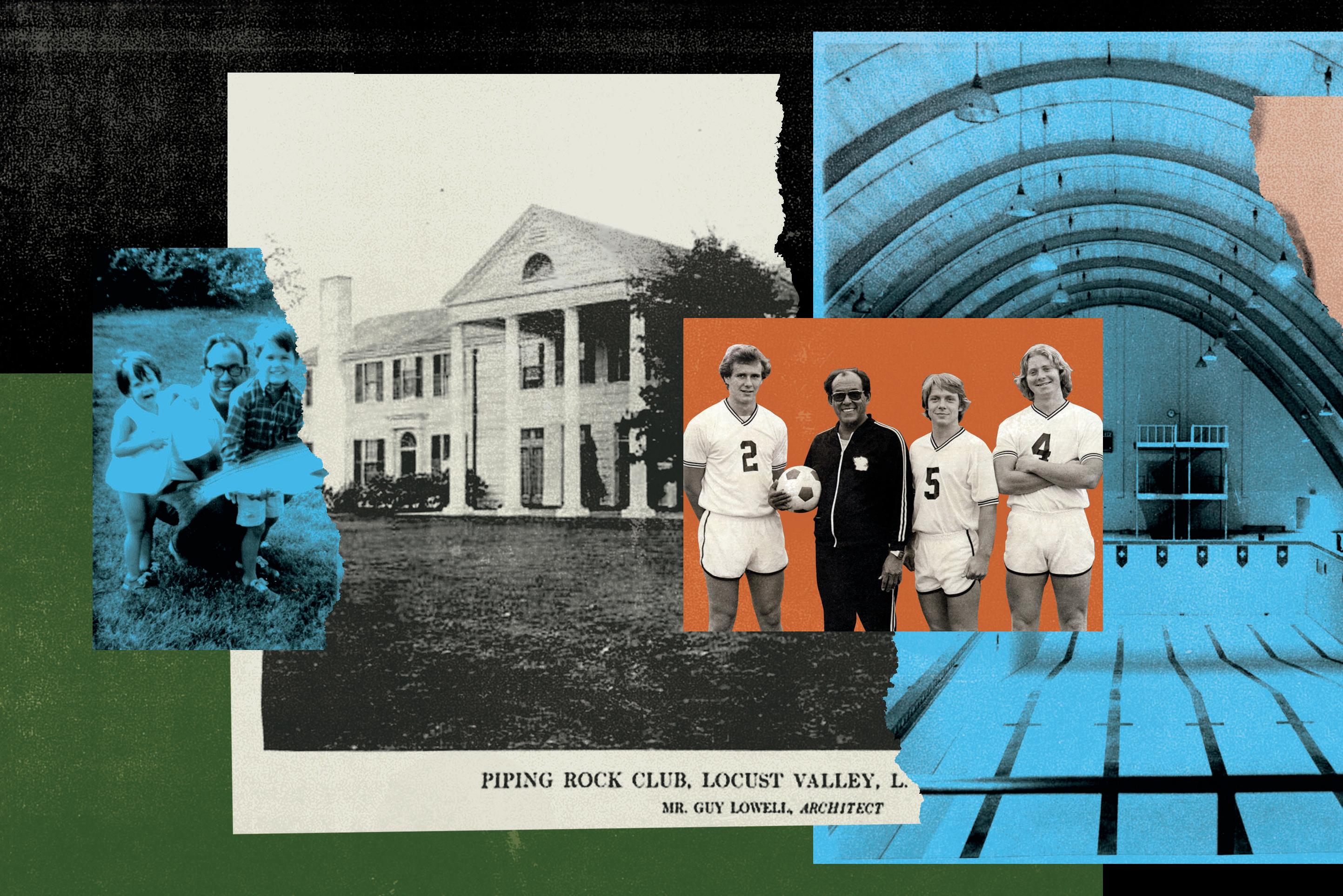

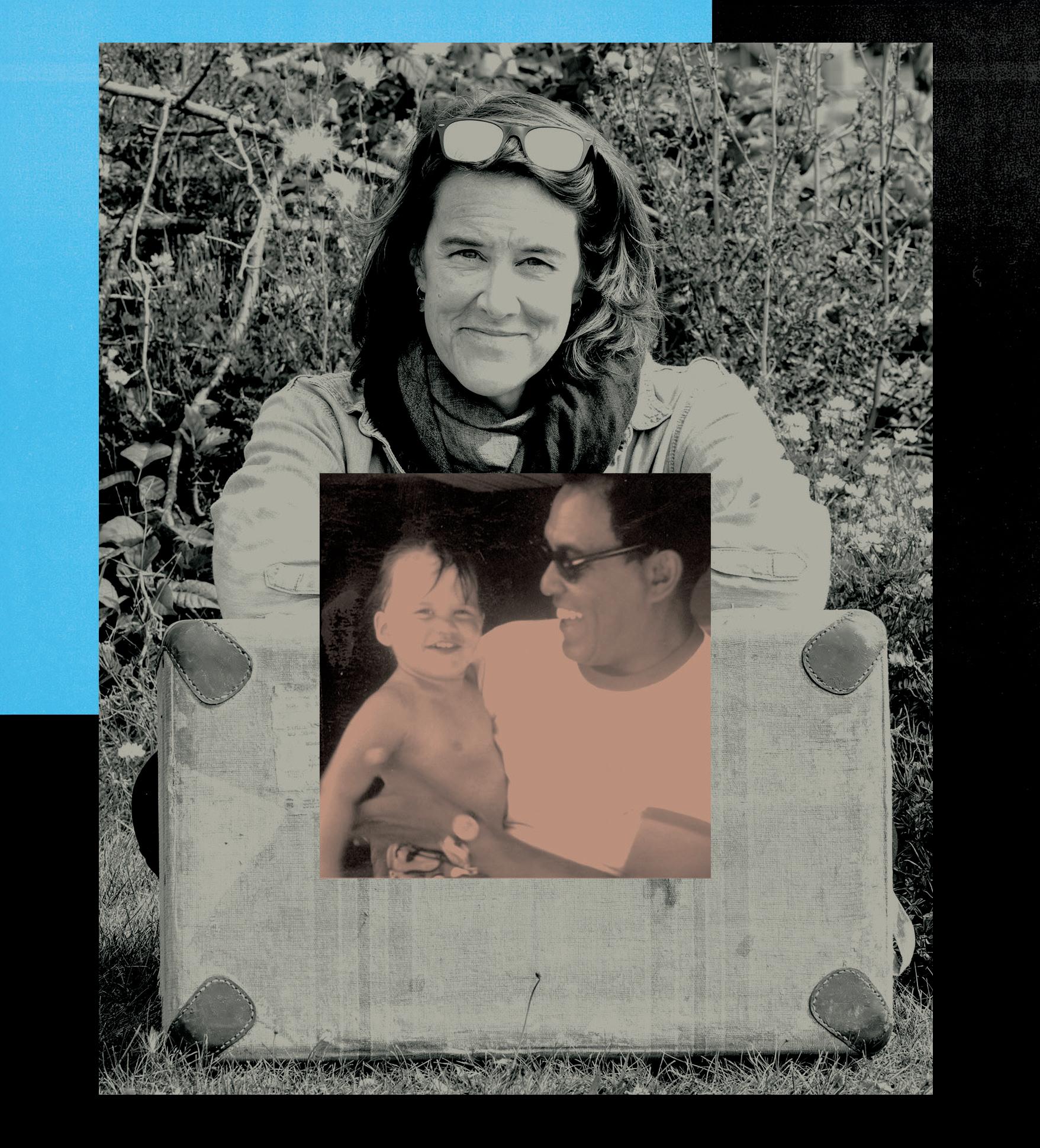

38 A Suitcase of Stories

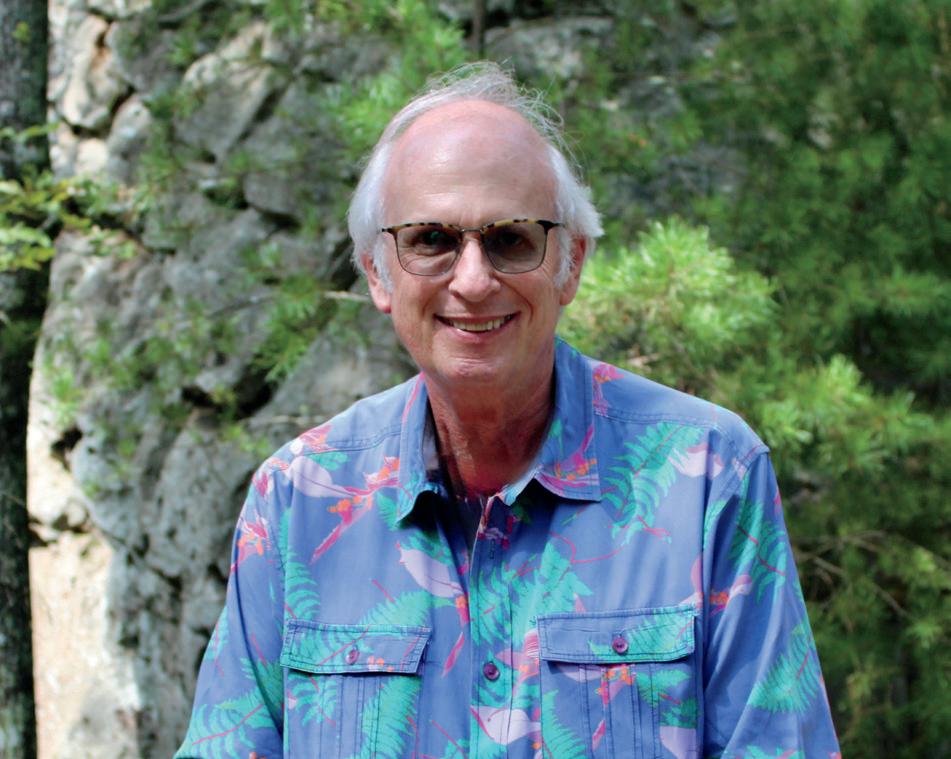

Coach Charlie Butt’s remarkable journey from acclaimed athlete to legendary Bowdoin coach and squash champion began with a dramatic swim in a Chinese harbor. This summer, his daughter, Catie, published a book that tells his unlikely and impressive story.

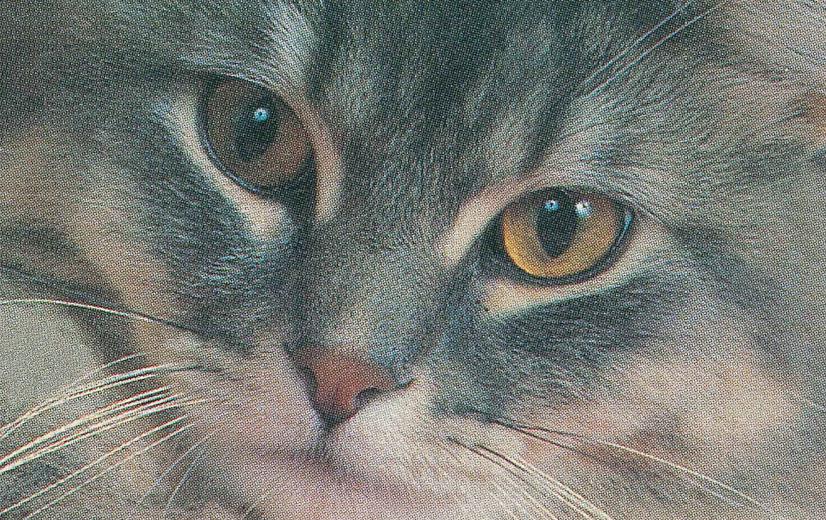

Professor Dallas Denery reveals a story from his life before academia that involves punk rock and a magazine for cat lovers.

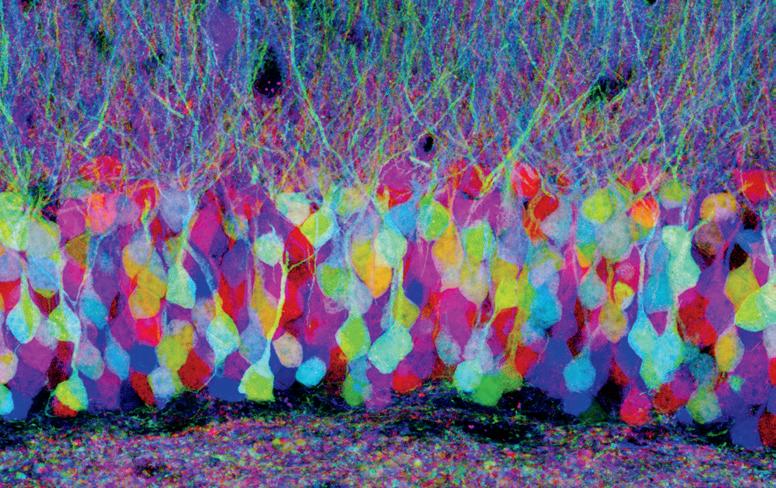

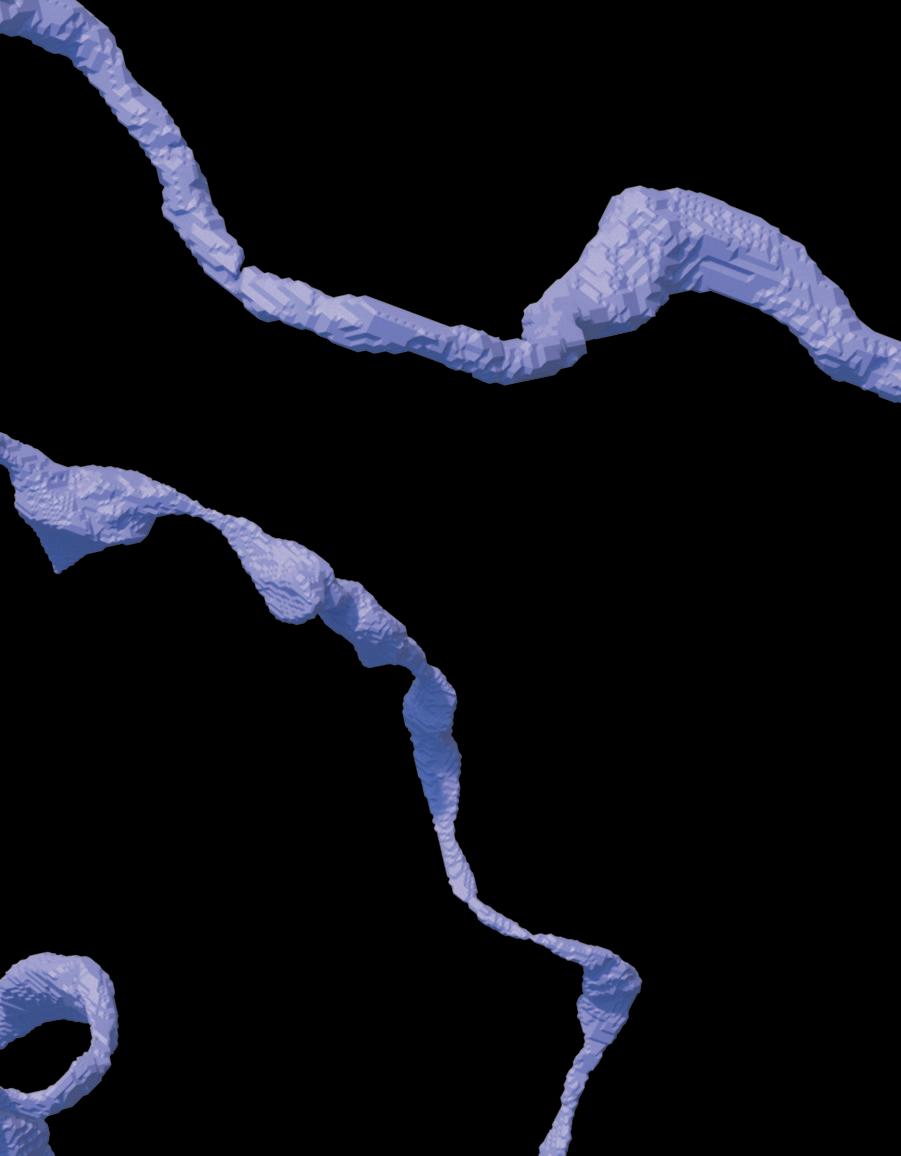

22 The Brainbow Connection

As a kid, Jeff Lichtman ’73 wanted to examine the world. Now a neuroscientist, he is on a quest to map the brain.

After years of planning, Bowdoin is taking steps to preserve the legacy of the Pines. Much of it begins with life-giving light.

5 Sixty Years of Song: Piano instructor Naydene Bowder hits all the notes in recounting sixty years of teaching and learning through music.

7 Dine: Bowdoin Dining shares one of their many delicious vegetarian recipes, a portobello mushroom napoleon with a balsamic vinaigrette.

8 Fizz Biz: Bowdoin and Polar Beverages, the 143-year-old family business owned by Ralph Crowley Jr. ’73, share more than a mascot.

11 A Gift for Art: A gift has made possible an oral history with former—and first woman—museum of art director Katharine J. Watson.

15 Ultimate Road Trip Companion: An online road trip game “dropped by” student radio station WBOR this summer for more than 66,000 listener hours.

46 A Toolbox for Floods: Professor and expert on flooding Sam Brody ’92 on how communication and planning can shape a safer future.

Smiles spread at Crystal Spring Farm in August as bagel lovers descended on the happy place that was the Maine Bagel Bake-Off. Sponsored by the Maine Grain Alliance, the invitation-only contest was the centerpiece of that weekend’s Brunswick Farmers Market. While bagel makers vied for the top prize with blueberry, garlic, and onion varieties, there was no denying a pervasive Bowdoin flavor to the event. Sam Silverman ’14 (pictured), known as New York’s “bagel ambassador” for having founded BagelUp, the company behind NYC Bagel Tours, the New York BagelFest, and a growing number of bagel-centric experiences, was part of the judging panel—alongside Tristan Noyes ’05— and the best bagel award went to Jeff Mao ’92, founder of Knead and Nosh in Brunswick.

YOUR MULTIDISCIPLINARY essays in praise of uncertainty (“No Doubt,” Spring/Summer 2025) addressed a central idea that has emboldened my professional practice in classrooms, courtrooms, and chapels, as well as in my family relationships. The idea is that, contrary to our cognitive preference for certainty and simplicity, the natural way of things is uncertainty. So, let’s embrace it, rather than erase it.

The teenage student seeking the “right” answers; the discerning juror seeking a verdict beyond a reasonable doubt; the penitent prayer seeking an answer to life’s essential questions— all are influenced by the age of reasoning, its pursuit of certainty, and its elusive effort to eliminate doubt.

And yet, it is the hard science of nuclear physics that has given us Walter Heisenberg’s uncertainty principle. I’m no physicist, but my understanding of the Heisenberg principle is that electrons continuously revolve around the nucleus of each atom. Their position can never be fixed in a certain position, since revolutionary motion is their natural way of being.

The recent popular movie Heisenberg tells of the explosive consequences of nuclear bombs when we manufacture the cessation of atomic revolutions. Heisenberg’s uncertainty principle

I was intrigued with your “Juicy Couture” article on alumna Ruthie Davis ’84 and her luxury high-heeled footwear. Her collaboration with Cassidy and Kelsey Tucker in their support of the Detroit youth community is to be celebrated. However, as a podiatrist and public health practitioner, I caution your readership when considering the Candy and Yardley spiked heels of six and four inches. One needs to condition themselves with appropriate break-in periods

suggests that the basis of matter is uncertainty. It’s interesting to infer that the basis of what really matters may also be uncertainty.

Bowdoin’s liberal arts curriculum that encourages students to explore diverse disciplines nurtures this foundational understanding of the revolutionary principle of uncertainty.

Thank you to the authors and editors for making a compelling case in praise of doubt. Certainty is often overrated!

Chris Kraus ’82

and practice of heel-toe walking prior to initiating this level of high-heeled shoes. Not for the novice and never without risk.

James J. DiResta P’99

One of my book club members sent me this [Ed.: after reading Matt’s essay, “The Sure Thing,” in the feature about uncertainty in Spring/Summer 2025]: The “monkey Shakespeare” concept, stemming from the

Infinite Monkey Theorem, is mathematically debunked as practically impossible within the universe’s current lifespan. While the theorem states that an infinite number of monkeys typing randomly for an infinite amount of time would eventually produce any given text, including Shakespeare’s works, studies have shown that, even with all living chimpanzees typing constantly, it would take longer than the universe’s estimated lifespan to achieve this.

Matt Bitonti ’00

MAGAZINE STAFF

Editor

Alison Bennie

Designer and Art Director

Melissa Wells

Managing Editor

Leanne Dech

Senior Editor

Doug Cook

Design Consultant

2Communiqué

Contributors

Adam Bovie

Jim Caton

John Cross ’76

Cheryl Della Pietra

Trevor Geiger

Rebecca Goldfine

Sophaktra Heng

Scott Hood

Micki Manheimer

Martin Mbugua

Janie Porche

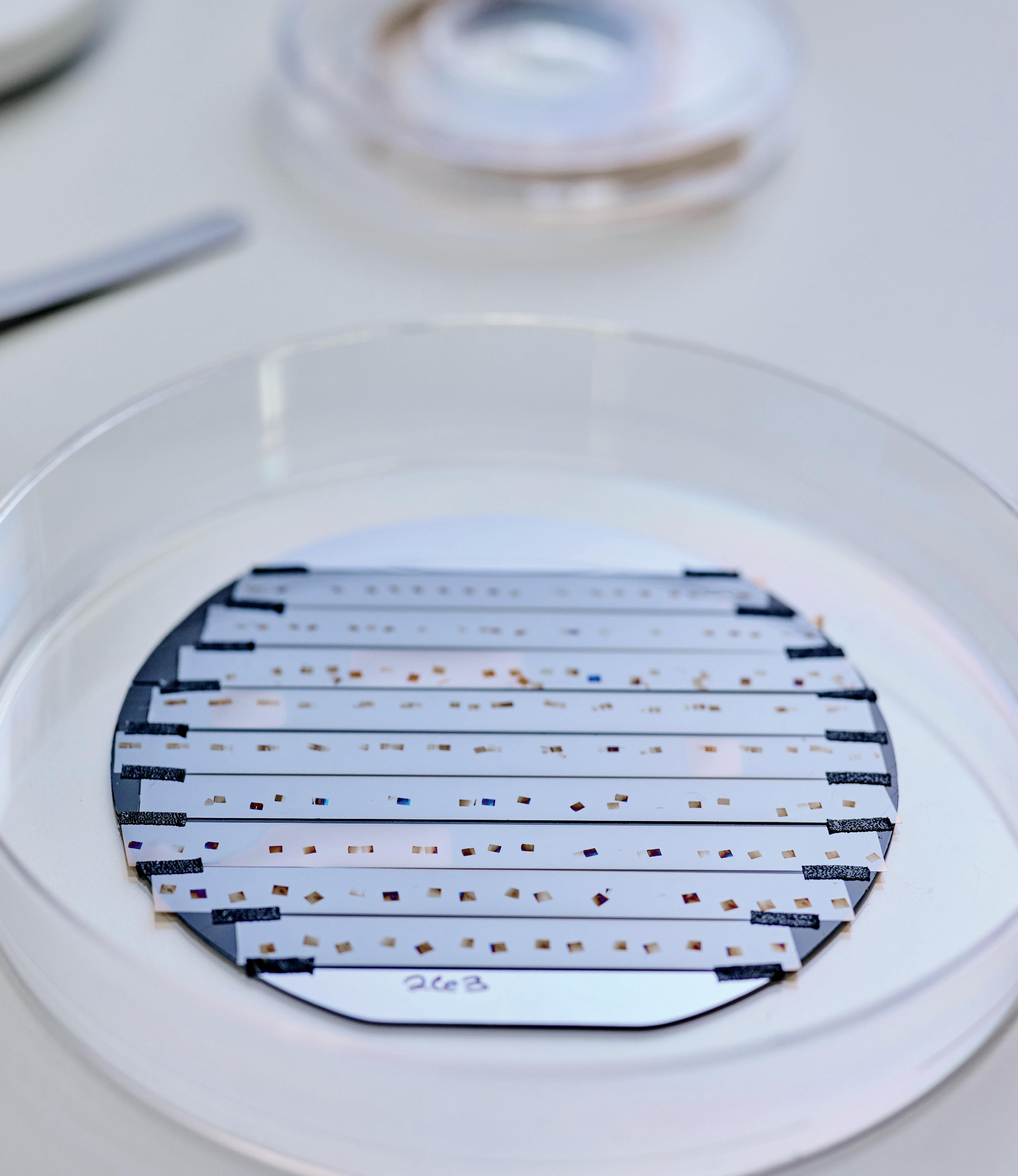

Tom Porter

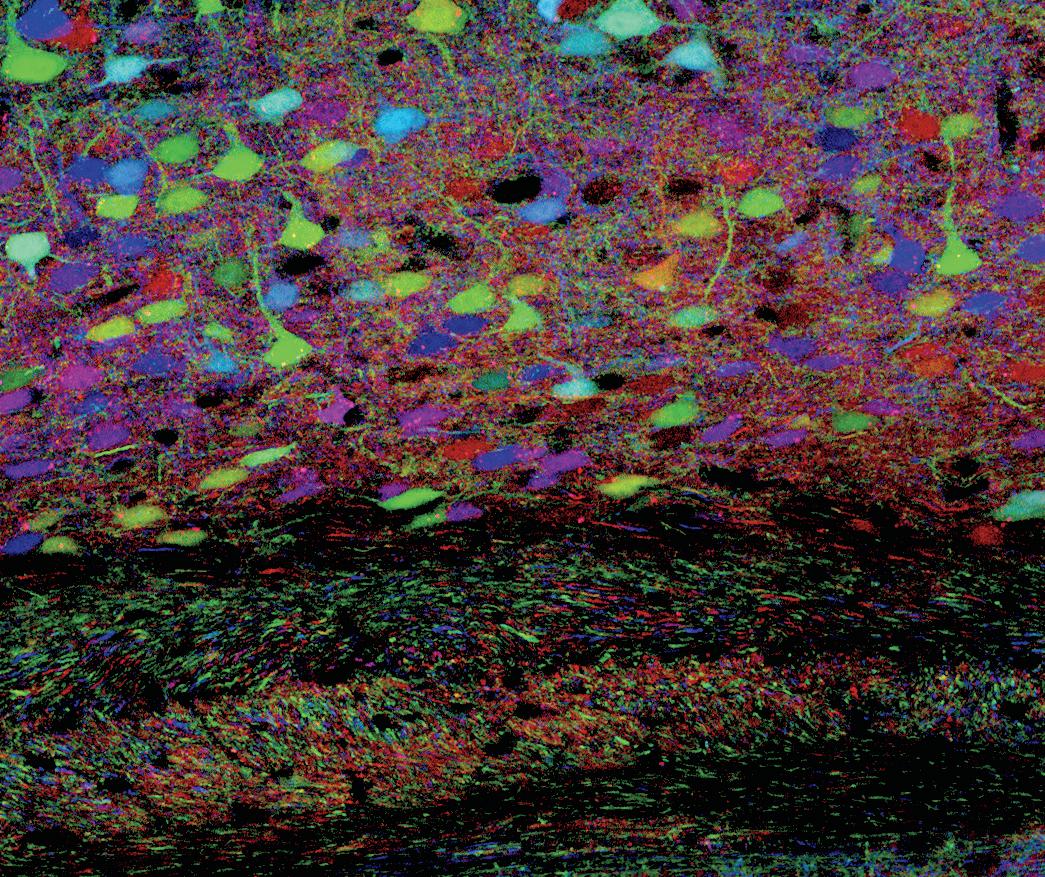

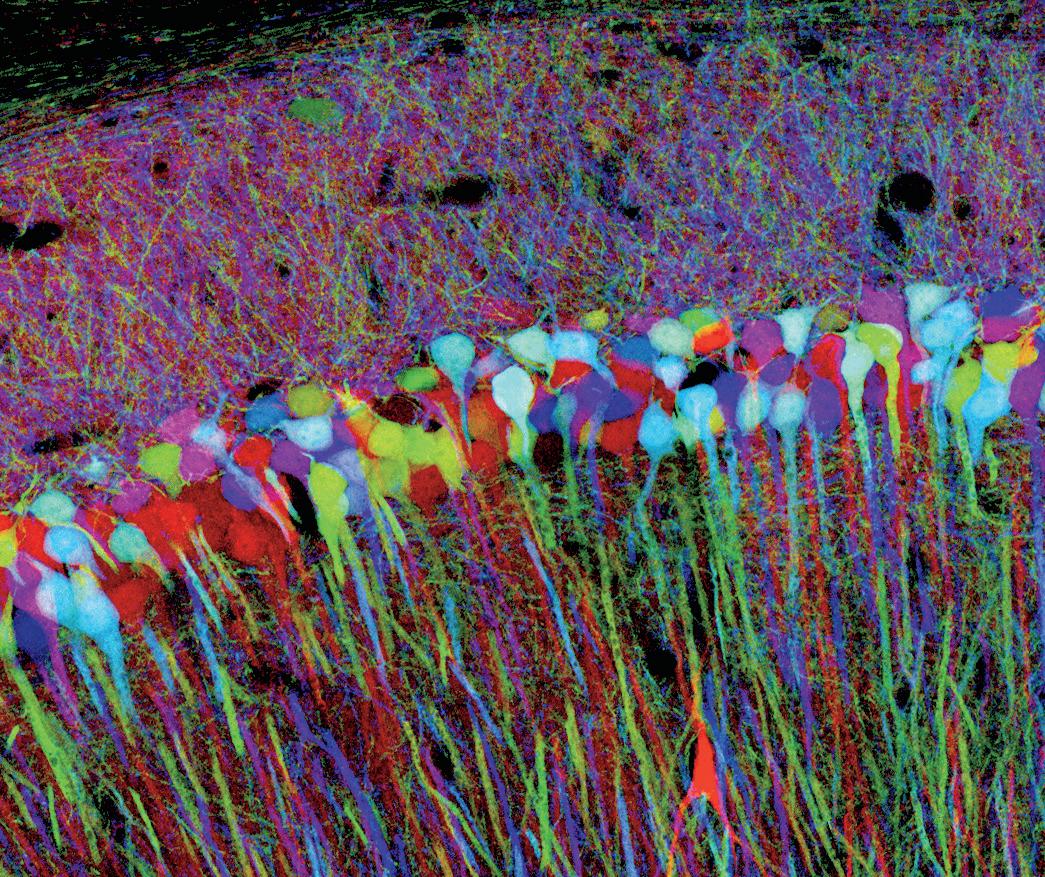

On the Cover: Brainbow image courtesy of Lichtman Lab/Harvard (front). Slices of brain in a petri dish by Jared Leeds (back).

BOWDOIN MAGAZINE (ISSN: 0895-2604) is published three times a year by Bowdoin College, 4104 College Station, Brunswick, Maine, 04011. Printed by Penmor Lithographers, Lewiston, Maine. Sent free of charge to all Bowdoin alumni, parents of current and recent undergraduates, members of the senior class, faculty and staff, and members of the Association of Bowdoin Friends.

Opinions expressed in this magazine are those of the authors.

Please send address changes, ideas, or letters to the editor to the address above or by email to bowdoineditor@bowdoin.edu. Send class news to classnews@bowdoin.edu or to the address above.

NAYDENE BOWDER CLASSICAL PIANO AND HARPSICHORD INSTRUCTOR

In 1939, every Saturday my mother would take me to WGAN in Portland where they had a children’s talent show, and I would sing on the radio. Somewhere there’s a recording of me at two singing, “Climb up my rainbow, slide down my cellar door, and we’ll be jolly friends forevermore.”

My first day at Juilliard, I was in saddle shoes and a plaid skirt, and there was a girl in front of me in line in the same; everybody else was in concert black. We started talking, and she said, “You sound like a Maine lobsterman,” and I said, “You sound like a Kennedy.” It turned out to be Dianne Goolkasian Rahbee, a wonderful composer—my piano students have won competitions all over the world playing her pieces. I was home in Maine in 1962 after getting my degree, and [Professor of Music] Bob Beckwith said, “I’ve got two or three boys down here at Bowdoin who want to continue piano. Could you come and give them lessons once a week?” That was the beginning of sixty years teaching here.

There’s a huge difference between Bowdoin before the ’70s and after. It’s been chaotic but so colorful—we don’t just have red, yellow, and blue, but everything in between, and we can mix and match as we choose. It’s fantastic.

I remember, with a couple of buddies from Girl Scouts, wondering if we would live to be sixty. I thought, “Make the most of it,” you know? I feel like a child. I hope I never grow up. I would wish for every student I teach, for every child I raise, for every person in the world, to find what they love. Love is what it’s all about.

The most wonderful thing I’ve discovered is this never stops. I’m not done yet! I will say, if the people we are leaving this country to are represented by students I have contact with at Bowdoin, I will leave this world very confidently.

For more from this interview, visit bowdoin.edu/magazine.

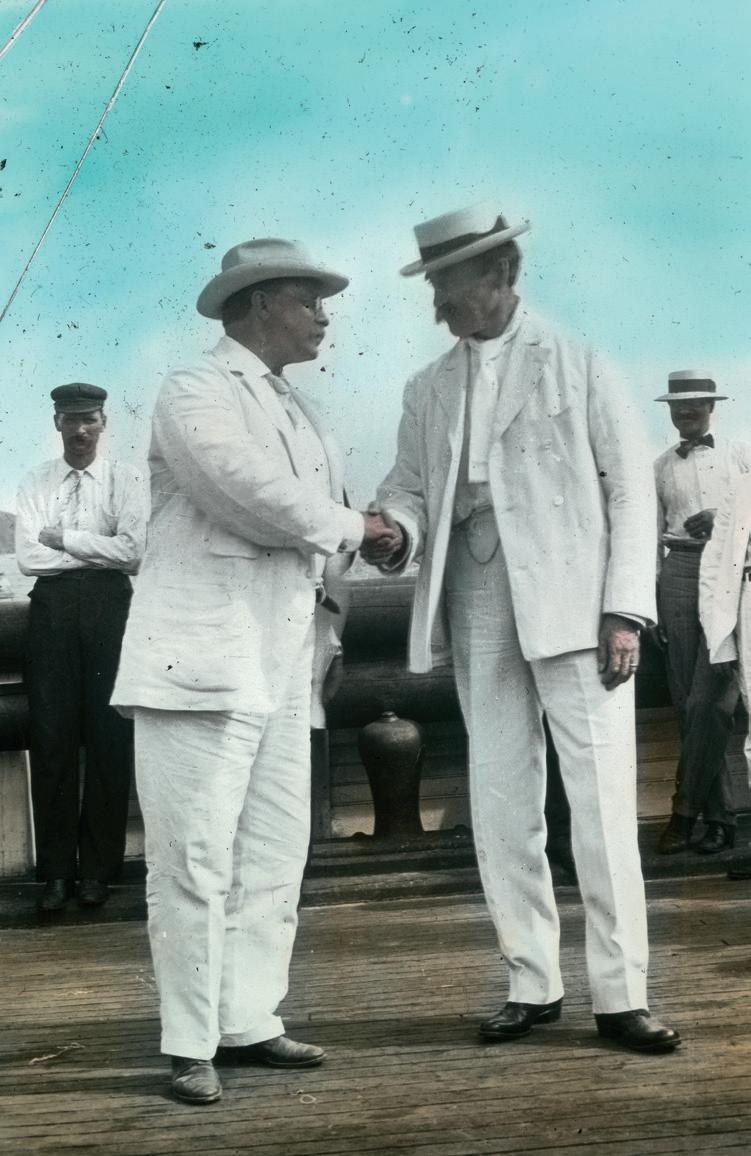

The teddy bear may have been created in honor of President Theodore Roosevelt, but it’s a polar bear from Robert Peary that lies in a place of honor at his “Summer White House.”

PRESIDENT Theodore Roosevelt famously advocated for speaking softly and carrying a big stick. On the home front at Sagamore Hill, his “Summer White House” in Oyster Bay, Long Island, a rather ferocious-looking polar bear rug still speaks volumes, representing admiration and gratitude from none other than Arctic explorer Robert Peary, of the Class of 1877.

Across the foyer from Roosevelt’s home office, the rug is splayed—head reared back with teeth bared—in a parlor that, according to National Park Service tour guides, served double duty as a sitting room for Roosevelt’s second wife, Edith, and as a waiting area for those meeting with her husband during his roles as governor of New York and then vice president under President William McKinley before he assumed the presidency after McKinley’s assassination.

“Peary was generous in giving souvenirs to his sponsors and supporters,” said Genevieve LeMoine, curator and registrar at the PearyMacMillan Arctic Museum.

President Roosevelt openly supported Peary’s efforts and was instrumental in arranging for his leave of absence from the US Navy so that he could continue his Arctic explorations.

Following a failed 1902 attempt to reach the North Pole, blamed on the limitations of using chartered ships, Peary set a course for a more capable ship and, with public support from the country’s twenty-sixth president, was able to muster the funds to begin construction of what he would name the SS Roosevelt

When Peary’s first attempt with the new vessel in 1906 again fell short of his goal, the Roosevelt

limped home badly damaged by ice, but Peary was undeterred, and his relationship with the president was as warm as ever.

Having made repairs to the ship, Peary stopped to visit Roosevelt on his way back to the Arctic in July 1908. A glass lantern slide in the Arctic museum’s collection captures an image of the explorer and president shaking hands, both decked out in white suits and hats.

The following spring, Peary made his successful trek. He sailed as far north as possible, to Cape Sheridan on the northeast coast of Canada’s Ellesmere Island, froze the Roosevelt into the ice, and used her for a base of operations as he and his team of Westerners and Inughuit used dog-drawn sledges to get to the North Pole.

It’s unclear at what point Peary gifted Roosevelt the rug, but we do know what happened to the ship that gave rise to that gesture of gratitude. When the Roosevelt was no longer useful to Peary, it was used for commercial shipping and, on one such journey, ran aground near the Panama Canal, where it remains on the ocean floor.

Professor of English Aaron Kitch has a special scholarly interest in William Shakespeare. He also has a side-hustle as a rock musician—chances are you’ve seen him in the ’80s cover band Racer X on campus. Kitch’s latest musical project is a departure from both. True Believer, available on a range of streaming platforms, is a concept album set in the Nevada desert around the fictional utopian community of Nazareth. Characters include a pair of charismatic preachers, a recovering alcoholic, an exotic dancer, and a queer teenager. The plot features, among other things, a doomed love affair, persecution by federal authorities, and an alien abduction. Kitch plays nearly all the instruments on the album, and he nods to his academic work by referencing Shakespeare’s Sonnet 43 in the song “Darkly Bright,” and there are other Bowdoin connections. The Meddiebempsters sing backup on the tracks “Testify” and “Fade Away,” and the album cover is the design work of art professor emeritus Mark Wethli.

Portobello mushrooms are actually the most mature version of the common white button mushroom, one stage above the cremini— all are part of the Agaricus bisporus family in different phases of development.

Recipe by Bowdoin Dining

This recipe makes a vegetarian side that looks fancy and tastes great. To make it a main dish, just make more!

1 tablespoon honey

1 ½ teaspoons Dijon mustard

¼ teaspoon salt

¼ teaspoon fresh ground black pepper

2 tablespoons balsamic vinegar

7 tablespoons extra virgin olive oil, divided

4 medium to large portobello mushrooms, approximately 8 ounces

8 thick slices summer squash, approximately 6 ounces

8 thick slices zucchini from a medium, approximately 6 ounces

4 thick slices red onion, approximately 4 ounces

4 medium slices tomato

12 medium slices fresh mozzarella from an 8-ounce ball

4 tablespoons balsamic vinaigrette (recipe at right)

4 ounces fresh basil, chopped or cut into chiffonade

Make the vinaigrette: whisk the honey, mustard, salt and pepper, balsamic vinegar, and three tablespoons of the olive oil in a small bowl. Set aside.

If using a grill or grill pan, brush the mushroom, summer squash, zucchini, and onion with the remaining olive oil on both sides. Grill over mediumhigh heat, turning once, so that each side is seared and the slices are softened but retain some structure. If using a skillet, heat the olive oil in the skillet (preferably cast iron) over medium-high heat and cook the mushroom, summer squash, zucchini, and onion, turning once and cooking the same way you would on the grill. Depending on the size of your skillet, you may have to cook the slices in batches so as to not crowd the pan and steam rather than sear them.

To build the napoleons, layer, starting with the mushroom, then alternating with the summer squash and zucchini, using two slices of each per stack. Place the stacks on a baking sheet or other oven-safe pan.

Top each stack with a grilled onion slice, a slice of fresh tomato, and three slices of mozzarella cheese. Drizzle each with a tablespoon of balsamic vinaigrette. Finish in the oven at 350 degrees for about 5 minutes or until the cheese is melted.

Top with the fresh basil and serve.

forced

Despite the mascot, Polar Beverages was not inspired by Bowdoin College. But a lot of other meaningful connections have bubbled up over the company’s long history.

Illustration by Jackson Gibbs

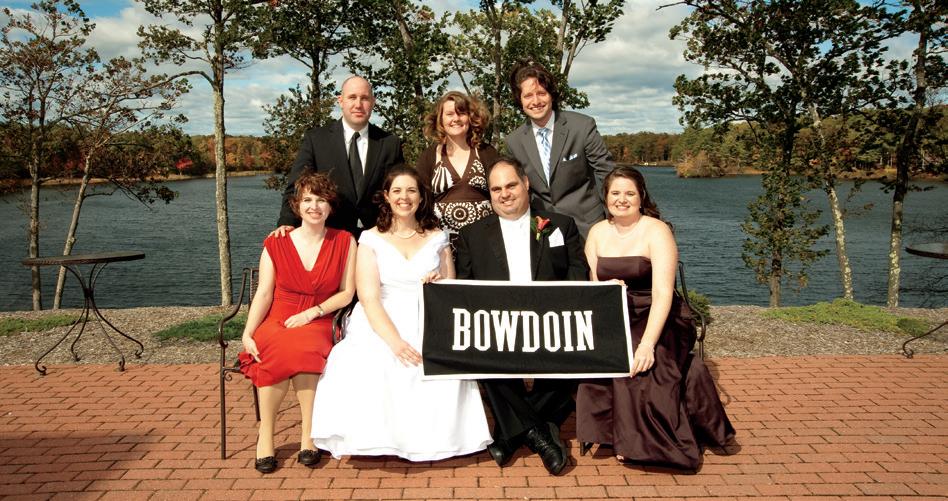

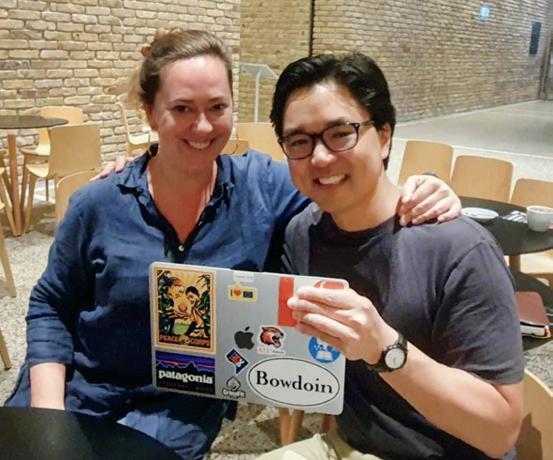

Polar Beverages, the largest independent sparkling beverage bottler in the country, has been in the Crowley family for 143 years. The company, based in Worcester, MA, began in 1882 as Crowley Ball Brook Straight Whiskey, when Dennis Crowley would hit the streets on payday, selling whiskey from a horse-drawn carriage for a dollar a bottle. Four generations on, his great-grandson, Ralph Crowley Jr. ’73, has led the company through tremendous growth and expansion as president and CEO since 1992. “Many of our friends assumed Polar Beverages borrowed the name and mascot from Bowdoin,” said Crowley. “Interestingly, the College became the Polar Bears in 1913 after Robert Peary visited the North Pole—Polar Beverages has had the name and mascot since 1882.” Ralph was the first in the Crowley family to attend Bowdoin, but there has been a steady stream since: Three of Ralph’s children attended—Kathryn ’02, who married Matthew McNeal ’02, Andrew “Dewey” ’09, and Sarah ’11; another daughter, Elisabeth, is married to Daniel McKinnon ’98. Crowley’s brother-in-law is Thomas McNamara ’78, and his nephew is Henry McNamara ’13. That’s a lot of Polar mixing!

The company introduced its polar bear mascot, Orson, in the 1960s, and a nearly twenty-five-foot version has waved to cars on I-290 from the roof of a company building ever since.

Polar is currently the official seltzer partner of

Crowley

Following the wedding of Meghan Markle and Prince Harry in 2018, seasonal flavors included Vanilla Zen, “a resplendent recipe of noble vanilla with serene touches of pomegranate” that the company said was “inspired by our new American princess.”

As kids, Ralph and his younger brother Christopher sold bottles from the back of a truck at Holy Cross football games. Later, they worked the stadium, barking, “Get your ice-cold Polar beverages!”

America’s Test Kitchen named Polar Original Seltzer the best in its taste test of sparkling waters, and Slate was equally sparkly in its praise: “When a bottle of Polar tells you to expect a Ginger Lime Mule, brace yourself to be donkey-kicked in the tongue as hard as the flavor of a beverage with no added sweetener can possibly muster.”

Around Town

The scenic Dionne Farm, the last remaining piece of the original Crystal Spring Farm, is fitting into place.

IF YOU EVER ran or biked on Pleasant Hill Road during your time at Bowdoin or took the back way to Freeport, you probably remember the Dionne Farm, one of Brunswick’s most beloved rural landscapes.

It had been part of the larger, 356-acre Crystal Spring Farm purchased in the 1940s by Maurice Dionne, who, with his brother Bertrand, a veterinarian and member of the Class of 1937, operated a dairy operation that in its heyday sold locally popular Dee’s milk and ice cream. Maurice’s daughter Donna Dionne, a member of the Class of 1973, was the first woman named to Bowdoin’s Phi Beta Kappa chapter.

Keisha Payson, Bowdoin’s director of sustainability, rented an apartment on the property in the mid-1990s. “We got to spend three summers there” marveling at the views of the open fields and the bird life, she said. John Cross ’76, secretary of development and college relations,

has an even more personal connection. “In the span of four years, Dr. Dionne delivered my brother, my sister, and me at the Brunswick Community Hospital that he founded, formerly on the corner of Cumberland and Union streets in Brunswick.”

The farm is itself experiencing a kind of rebirth. Over the years, large parcels of the original property that had been sold off have been acquired by the Brunswick-Topsham Land Trust (BTLT), but one piece has long been missing—the twenty-five-acre homestead with the picturesque barn, atop of which sits the original Brunswick Town Hall clock, relocated in the 1960s before the town hall was demolished. In winter 2024, that final piece began to fall into place. A friend of the trust acquired the land and offered BTLT the gift of time to raise the funds to complete the original Crystal Spring Farm.

The seller, who remains anonymous, granted BTLT a two-year, private $2 million loan with the stipulation it be paid off by April 2026.

The trust met that goal early and is now planning a longer, more comprehensive campaign to fill a variety of needs, including moving the Saturday morning farmers market from its current location across the road to the Dionne Farm by early next summer.

Eww, David If you’re a little bit Alexis or find yourself “trying very hard not to connect with people right now,” you are clearly a fan of the television series Schitt’s Creek and may have caught a reference or two to a polar bear shot and wondered, why has this most enigmatic of potations been so cruelly withheld from the grand narrative that is my life? No need to pop a pill, cry a bit, and fall asleep early, bébé—we have the recipe. Mix equal parts peppermint schnapps and white crème de cacao and shake with ice for twenty seconds before straining into chilled shot glasses. It’s a cool and refreshing alternative to the banana rosé or anything else you might select at Herb Ertlinger’s fruit winery. For those wanting extra zing, a splash of vodka may also be added. You just fold it in.

Listen

In 1977, Katharine J. Watson joined the College as the first woman director of the Bowdoin College Museum of Art (BCMA), a post that she filled until 1998 and that at first also included directorship of the Arctic museum. Those twenty-plus years, which began not long into coeducation at Bowdoin, saw a great deal of change at the College and in the world. An anonymous donor wanted to capture Watson’s thoughts and stories for posterity and made a gift to provide an oral history. Watson sat for eight interview sessions with Edgar Allen Beem, freelance writer and author and former Maine Times art critic, last spring and spoke extensively of her career, artists and colleagues and exhibitions from her time at the BCMA, why art matters, her favorite work in the museum’s collection, and more.

Find them all on the library’s digital collections site at bowdo.in/katharine_watson.

Safe Passage celebrated its twenty-fifth anniversary on September 25 in the First Congregational Church in Yarmouth, Maine, a location that reflects the organization’s ties to the state.

Yarmouth native Hanley Denning ’92 founded Safe Passage in 1999 to tutor children whose families made their living scavenging and recycling trash from a huge landfill in Guatemala City.

Since its founding—and continuing after Denning’s death in 2007 in a car accident—scores of people from Maine have contributed to its impact.

“Today we have over 10,000 individuals in our database from Maine,” said development director Rachel Meyn Ugarte. Hundreds of volunteers—including Bowdoin student and alumni groups—have traveled to Guatemala City to volunteer. Between 2003 and 2019, 160 Bowdoin students on fourteen alternative spring break trips worked with Safe Passage.

“The bridge from Maine to Guatemala is so tangible. That is something we want to celebrate with Mainers, whose foundational support was pivotal to Safe Passage’s success,” she added. Safe Passage now runs schools from early-childhood programs to ninth grade for more than 500 students, supporting them as they continue at local high schools. It will open a new middle school this winter.

Many program participants have inspiring stories. The first to graduate from medical school started a job this year at the city hospital. Another, trained as a mechanical engineer, is working at the airport. Safe Passage’s educational model could be an example for other communities, Meyn Ugarte said. “We’re working at the root of migration,” she added. “As these families are able to thrive in Guatemala, they don’t need to migrate to the US.”

Photographer Gordon Parks documented American life and culture from the 1940s into the 1970s. Born into poverty and segregation in Fort Scott, Kansas, Parks was inspired by photographs he saw in a magazine, bought his first camera at the age of twenty-eight, and became a self-taught photographer.

In January 1944, at the height of World War II, Parks photographed Herklas Brown, owner of the general store and Esso gas station in Somerville, Maine. Parks traveled to the state under the auspices of the Standard Oil Company to record its contributions to the war effort and to document the home front. His photographs chronicled oil and gas facilities and those who operated them, Esso gas station owners in small towns, and people whose work depended on fuel and other Standard Oil products. Consistent with his work before and after, Parks made it his mission to get to know his subjects and show their humanity. He photographed Brown at his Esso station, in his store, and with his family at the dinner table. Parks spent a month in Maine that winter and then returned in August to resume his work in the state. At a time when transportation, food, and lodging were a challenge, and notably as a Black man traveling alone, Parks nonetheless created a compelling documentary record of rural America that offers insight into this historic moment.

In partnership with the Gordon Parks Foundation, sixty-five of Parks’s photographs for this project are on view at the Bowdoin College Museum of Art in the exhibition Gordon Parks: Herklas Brown and Maine, 1944 through November 9, 2025.

An employee of Standard Oil Company, Somerville, Maine, February 1944.

Alumni

An alumna and her husband were inspired by their roots in food and farming to create meat stick products they feel good about.

WHEN MOST PEOPLE think of meat sticks, “high quality” might not be the first thought that comes to mind. The Newcastle, Maine, farm Singing Pastures is on track to change that. Touting their Craft Meat Sticks as “the meat stick for people who don’t usually eat meat sticks,” Holly Jones Arbuckle ’91 and her husband, John, have set out to create a staple snack for clean eaters looking to sink their teeth into something natural. Their efforts have been rewarded, with their Roam Sticks products winning several awards at competitions both at home in Maine and across the country. The pasture-raised pork stick took home the $25,000 first prize on the reality TV show Greenlight Maine, in which Maine entrepreneurs make innovative business pitches to a panel of judges. They also won the $5,000 prize at the Naturally New England Pitch Slam Competition, which focuses on businesses specializing in natural products. That prize came with an invitation to the national competition Naturally Rising, where Singing Pastures won an Emerging Impact Award. Continuing to innovate, they have recently added grass-fed bone broth and collagen to the sticks. Celebrating their wins, Holly dispelled the idea of “rugged individualism in farming,” saying, “If you are successful at anything, someone helped you”—an inspiring message in what may be an unexpected package.

Campus bikeshare bicycles have a new look this year. The seven Bowdoin bikes, custom-made by Priority, have three speeds, fenders, and a rubber chain to prevent snags and grease stains. After completing a quick online safety course, students can check them out at the library circulation desk and then grab them at a special bike rack just outside. Bikes are trackable in case of any problems, and they must be returned by the time the library closes. Each includes a lock and a basket for trips into town and comes with a collapsible helmet— and some strong encouragement to use it.

Master luthier Dana Bourgeois ’75 is celebrating two big anniversaries this year— his fiftieth Bowdoin College reunion and fifty years in the business of building guitars. While the first brought him back to campus last May to reconnect with old friends and colleagues, the second milestone is being commemorated with the release of a 50th Anniversary Collection from his namesake, Bourgeois Guitars. Already a specialty business, producing around 400 instruments by hand each year, Bourgeois’s 50th Anniversary Collection is limited to just twenty-five guitars worldwide. Based on his iconic Soloist model, these anniversary instruments honor Bourgeois’s artistry, blending classic design with the innovative techniques that mark his half-century of craftsmanship.

Bourgeois unknowingly launched his career during his junior year at Bowdoin, when he built his first guitar, working out of his room in the fraternity now known as Quinby House. “It was crude. But it worked,” he said. Within a few years, he had opened a shop in Brunswick and earned a reputation as a skilled guitar repairman. But his love of learning, perfectionism, and deep respect for traditional guitar-making didn’t let him stop there. Five decades later, Bourgeois produces some of the highest-quality instruments on the market, with guitars famously played by Doc Watson, Natalie Maines, Luke Bryan, Ry Cooder, Sierra Hull, and many more. Still living in Brunswick, he commutes each day to his shop in Lewiston, Maine, where he continues to oversee the production of every guitar.

As Jane Austen’s 250th birthday approaches, English literature scholar Ann Kibbie says the great novelist’s real message goes beyond the world of love and romance.

THIS YEAR marks a landmark anniversary for fans of one of the greatest English language novelists. Jane Austen, who wrote about the lives and loves of the British landed gentry from the female perspective, was born on December 16, 1775. Those fans include Associate Professor of English Ann Kibbie, who teaches Austen and whose scholarship includes representations of money and capital in early modern literature. Kibbie says her favorite response to Austen’s work comes from the twentieth-century poet W. H. Auden. “He wrote that, despite the image of Austen as a prim and proper spinster, ‘You could not shock her more than she shocks me.’ What did he consider so shocking? Her focus on that most forbidden of subjects, not romance but money,” asserts Kibbie.

The summer road trip is a staple of Americana. Since the early twentieth century, the idea of loading family and friends into a car or camper to find out where the road takes you has symbolized discovery, freedom, and fun. In a new, online era, this kind of adventure can happen anytime and take you anywhere—including the headquarters of WBOR, Bowdoin College’s student radio station.

That’s where participants in the online game “Internet Roadtrip” found themselves earlier this year. The game uses Google Maps to put players in collective control of a virtual vehicle on a digital road trip by having them vote frequently on which direction to “drive,” whether to honk the car’s horn, and even what to listen to on the radio—a choice that depends on what actual stations are in range of their position on the map. In Maine, WBOR was frequently the station of choice, with the crew reporting 121,946 unique listeners during May and June—the road trip’s

peak period—for a total of 66,176 listener hours. Many of the players developed a friendly rapport with the student DJs at WBOR, who had noticed the unusual influx of new listeners and decided to connect with them by giving out travel advice and taking song requests. The result was a playful kind of cult following, with many players changing their screen names and making memes to express their newfound love for the station.

On the day the car “dropped by” the WBOR station office, DJ Janet Briggs ’25 was there to greet the players with classic French jazz—and a classic internet prank: “WBOR is rickrolling us,” wrote one player as they liveblogged the experience. (“Rickrolling” is when a link seems to take you one place but actually leads to the music video for Rick Astley’s 1987 song, “Never Gonna Give You Up.”) While the trip eventually took the players outside of the station’s range, many collaborated on a parting gift befitting an institution as characterful as WBOR: a collage of doodles, well-wishes, and praise for their new favorite radio station.

The Women Are Not Fine: The Dark History of a Poisonous Sisterhood

HOPE REESE ’06 (Brazen Books, 2025)

The poor and abused women of Nagyrev were desperate. Midwife Zsuzsanna Fazekas offered them a solution: arsenic. Journalist Reese pieces together archival records and the work of historians, sociologists, and psychologists to write not just a crime story but a timely, haunting exploration of what happens when women’s suffering goes unanswered.

Merchants of Knowledge ROBERT G. MORRISON

George Lincoln Skolfield Jr. Professor of Religion and Middle Eastern and North African Studies (Stanford University Press, 2025)

The

You Forget CHRISTOPHER

’82 (Subplot Publishing, 2025)

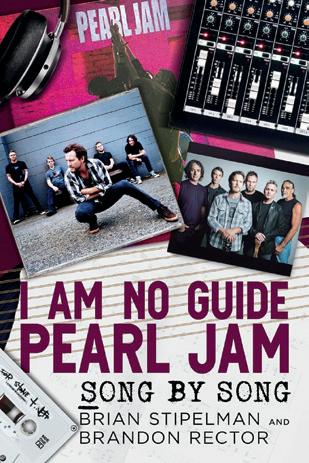

I Am No Guide: Pearl Jam Song by Song BRIAN STIPELMAN ’99 (Fonthill Press, 2025)

PAMELA M. FLETCHER ’89

Edith Cleaves Barry Professor of the History and Criticism of Art (Routledge, 2025)

28

15

By the Numbers

Each May at Bowdoin, the student body undertakes a collective spring cleaning. Dorm rooms are emptied of personal items to make way for the next occupants. Graduating seniors sift through their belongings to see what they’ll take with them and what they’ll part with.

To meet this tsunami of everyday objects, Bowdoin’s Sustainability Office ramps up its Give and Go recycling program to ensure as little as possible goes to waste. The office’s staff and student team takes on the task of collecting and sorting stuff for Goodwill or for Bowdoin’s Freecycle program.

If Give and Go is Bowdoin’s great purge, Freecycle is its great accumulation. In early June, gently used items for dorm rooms, kitchens, and common areas are organized and displayed at 10 Cleaveland Street, where summer students can peruse the free wares—like plates, desk lamps, and cutlery—and take what they need. In late August, Freecycle opens to first-years, international students, and transfer students, and then to students in all other class years.

28

34

200

35,400

Pounds of

5

Approximate number of

3,000

850

Items available for taking, including 135 plates, 130 desk lamps, 122 pots and pans, and 112

535

Opportunity A computer science intern at L.L. Bean becomes a social media star for the company.

IN THE SHORT promotional reel, Zai Yang ’27 walks across forest gullies and along shell-lined beaches. He stops in a field and pitches a tent with a friend, all while casually showing off a new line of the company’s more affordable clothing and gear. “The video was completely intern-led,” Yang said, crediting student workers Matthew Solan and Fisher Hirsch for directing and editing the short, and Ruby Hill for co-starring with him. Yang’s primary task as a summer intern was to use his computer science skills to build a new web application for customer service employees. But he also enjoyed all the outdoor trips he took with other interns—supported by free L.L. Bean gear—and the chance to work for a famous Maine company. “What drew me to them was how well they treat their customers, employees, and the earth,” he said.

Sound Bite

“Your future employer, whether a firm, nonprofit organization, or a government, will hire employees with skills that AI cannot replicate.”

—ASSOCIATE

PROFESSOR OF ECONOMICS ERIK NELSON, GIVING THE 2025 CONVOCATION ADDRESS

Athletics

Field hockey coach Nicky Pearson earned her 400th Bowdoin career win on September 17, as her team beat Wellesley 3-0, scoring all three goals in the first quarter. Head coach since 1996, Pearson is just the tenth coach in Division III field hockey history to hit the 400-win milestone. In her time at Bowdoin, she has led the team to eight NESCAC titles, a perfect 20-0 season, the College’s first-ever team NCAA championship, and four Division III crowns. She has been named NESCAC Coach of the Year nine times and National Field Hockey Coaching Association Coach of the Year four times.

From the baseball diamond at Fenway Park comes a real gem of a Trevor Story story, though the real tale is someone else’s to tell. The Red Sox shortstop’s fifteenth home run of the year ripped into the stands above Fenway’s famed Green Monster during a game with the Colorado Rockies. On that warm July night came the coolest move of the game: Ryan Jaillet ’29, wearing a Red Sox jersey and sitting in seats that were a high school graduation gift from his parents, reached up and just casually grabbed Story’s home run ball out of the air—barehanded. “It was the bottom of the seventh inning, and Trevor Story was up to bat,” recalls Jaillet. “I was mid-scoop on my ice cream when my brother yelled, and I looked up and saw the ball coming right to me. Everything just came naturally after that.” Naturally, indeed; Jaillet, who played catcher for Andover High School in Massachusetts, is planning to play ball for Bowdoin this spring. That three-run shot gave the Red Sox a commanding lead on the way to a win that night— and Jaillet the story of a lifetime and the ball prove it.

History

A career in historic preservation lets history majors channel their passion for the past into safeguarding buildings and neighborhoods that help tell the stories of a community.

Executive director of Lincoln County Historical Association

The association maintains three buildings on the National Register of Historic Places: the 1754 Chapman-Hall House (pictured), the 1761 Pownalborough Court House, and the 1811 Old Jail and attached 1839 Jailer’s House. Gilmore is also an expert in Maine’s grange halls, community buildings people have been gathering in for 125 years, originally to advocate for rural people, farmers’ rights, and women’s standing in the community. “Each of these places has an incredible story to tell as it helps us interpret local history, and we’re constantly working to uncover fuller narratives that deepen our understanding of the past,” she says.

Former director of Portland’s historic preservation program

Andrews is a big reason Portland is as charming and beautiful as it is. Among her many achievements are the rehabilitation of Lincoln Park—the city’s oldest park—and its distinctive cast-iron fence (pictured) and designating Munjoy Hill, once home to many immigrant workers, as a historic district. “Portland’s working-class neighborhoods tell as important a story as architectural gems and the wealthier neighborhoods,” she says.

Director of Victoria Mansion, a National Historic Landmark and museum in Portland

Victoria Mansion (pictured) was built in the mid-nineteenth century in the style of an Italianate villa by a businessman from Leeds, Maine, who ran luxury hotels in Boston, New York City, and New Orleans. Today the mansion strives to tell stories of its past, including those of servants who kept the house running and enslaved people who “unwillingly underwrote the construction” of the building. He says, “If you open yourself up and really look, you can connect with the people of the past through the things they left behind, buildings included. And this, like foreign travel, is an enlarging experience, one that broadens our perspective as human beings.”

Art

The Bowdoin College Museum of Art’s (BCMA) connection to the 2025 Met Gala is a study in how the holdings of the College’s world-class museum shine brightly, even outside its walls. The theme of this year’s gala, “Superfine: Tailoring Black Style,” was about exploring Black dandyism through fashion and is also the name of a companion exhibition at the Costume Institute at The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Included is the BCMA’s Portrait of a Gentleman, an oil-on-panel painting by an unidentified artist that “perfectly incarnates the ease and self-possession that we are hoping to convey,” said exhibition curator William DeGregario. The BCMA loans about a dozen works each year, said curator Cassandra Mesick Braun, adding that on that particular day there were three such requests on the docket, including another from the Met. Placement in such a prestigious setting can be a feather in the cap of a loaning institution, but it also can be a heavy and complicated lift. There are formal letters of request, myriad conservation concerns to manage—as well as meticulously safe shipping—and sometimes travel for a museum staffer to oversee an installation. For those whose work is providing art visibility, the effort involved in sharing pieces with new and different audiences is just part of the joy, even when arranged from afar.

Advice

To create a reading guide for his fellow graduates as they launch their careers, Chris Zhang ’25 reached out to faculty and staff for book recommendations.

“In the spirit of a liberal arts education and lifelong learning,” he began his appeal, “you can suggest any book…from your discipline that you believe would be of interest to a Bowdoin graduating senior.”

As he approached Commencement, Zhang said he felt a loss about the classes he hadn’t taken and the professors and staff he hadn’t met and wanted a last opportunity to learn from them. After sending out a request via the Campus Digest, he received submissions ranging from contemporary and nineteenthcentury novels to books on philosophy, history, politics, and self-improvement. Some who recommended books stayed true to their disciplines; others suggested books outside their fields.

Philosopher Aliosha Barranco Lopez thought seniors would appreciate Emily Austin’s Living for Pleasure, An Epicurean Guide to Life. The book, she noted, “will help you think about how to live a good life. It is philosophically rich and a joy to read.”

Classics professor Michael Nerdahl suggested More Everything Forever, by Adam Becker. “A fine illustration that insistent claims of scientific ‘rationality’ are driven by surprisingly irrational and ideological motives,” he wrote.

Max Lykins, a visiting assistant professor in government, thought graduates should read, or reread, the classic Russian novel The Brothers Karamazov. “A liberal arts education prepares us to ask enduring human questions, like what is justice? Is God real? Are we responsible for what we do? Brothers offers some of the most profound answers to those questions that I’ve ever read.”

Zhang is making his way through the list, starting with The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks, which received two nominations, The Mushroom at the End of the World, a Francis Spufford novel called Red Plenty, and Mr. g. The last one, recommended by astrophysicist Fe McBride, offers, she wrote, “an insight into the beginning of the universe, as told by a theoretical physicist in the form of a parable.”

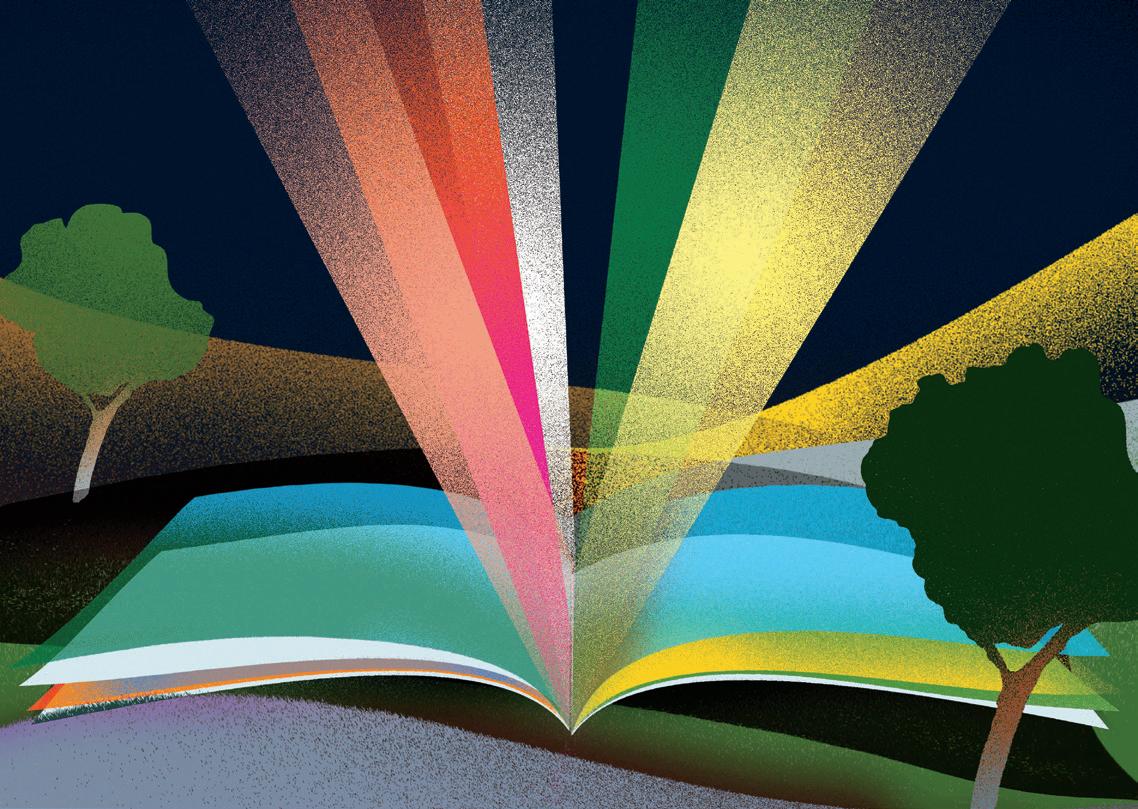

Professor of History Dallas Denery reveals a story from his life before academia, in which he begins as a punk rocker and ends as the author of a piece in a magazine for cat lovers.

SHORTLY AFTER the September 1989 Loma Prieta Earthquake in California, I found myself in need of a job. My four-year punk rock “career” had finally petered out in July. Our label had dropped us after our first album failed to find much of an audience beyond our local fanbase, and a three-month cross-country tour, though tremendously educational (among other things, I now knew where to find the world’s secondlargest twine ball), had done little to make it seem like stardom was just over the horizon. A bit disappointing to be sure, but not devastating, as a career in music wasn’t a particular ambition of mine. That aside, punk rock had never paid the bills, so all along I had been making ends meet summarizing legal depositions in my little apartment in San Francisco for a Berkeley law firm. Unfortunately, the earthquake had made it impossible to cross the Bay to Berkeley—the Bay Bridge was partially destroyed, and BART had been shut down for inspections. My days as a deposition summarizer, like my days in punk rock, were through.

Finances dwindling, I decided to look for whatever full-time work I could find, and so, one day, I walked from my flat in North Beach to a Financial District job placement agency. I met with a woman in her mid-forties (her name forgotten after all these years) dressed in black, with hair dyed to match her clothes. She asked about my work history, how fast I typed, when I could begin, and then she looked at my résumé. “I see here you studied philosophy in college. I study philosophy too, mostly in connection with my ongoing investigations into ancient Egyptian theosophy.” She then stood up, went to the window, and asked me to stand next to her. Both of us now looking down from twelve floors up at the busy afternoon streets, she asked, “Do you see all those people down there?” I told her that, yes, I could see them. “I sometimes think they are nothing more than ants that I could

squash with my thumb.” It was not the sort of thing I ever thought I would hear at a low-level corporate job interview, and its connections to theosophy—at least given my limited knowledge of theosophy—remained murky. I don’t remember how I responded, if I responded at all, but it did leave me with a somewhat warped expectation of the mysteries awaiting me just below the surface of the San Francisco legal world.

Within a week I was working full time as a legal secretary. I had never worked in an office, much less as a legal secretary, and while I wouldn’t call it fun, it was interesting. I suddenly found myself submerged for eight hours a day in a world entirely new to me, with its own traditions and passions. One of those passions, it turned out, was for cats. All of my coworkers were cat crazy. They covered their desks with framed cat photos and daily tear-away cat calendars. They hung motivational posters from the walls showing kittens suspended from twine (“Hang in there, baby!”). As I didn’t much care for cats and was the only man in the steno pool (as we already no longer called it in 1990), all of this left me outside much of the daily secretarial socializing and conversation that happened before and during and sometimes after work.

Sadly, none of this absolved me from having to join in one of the office’s core traditions, the Secret Santa. Every Christmas, every legal secretary needed to purchase one present to be randomly distributed among us at the annual office holiday lunch.

I am a terrible gift shopper and innately a bit of a cheapskate, but I did like my coworkers who, to a person, were easy to work with and made efforts to make me feel part of the team. My artistic impulses muted, what with my band no more and my days taken up transcribing endless tapes of letters and legal briefs, I decided that my Secret Santa gift would be a cat-themed Christmas story given to my fellow secretaries.

I could attempt to enter their cat-loving social world while not spending a cent and not actually having to participate in their cat-loving social world at all!

The result was “A Kitty Kat Christmas,” the story of how Kimberly Kitty Cat discovers the true meaning of Christmas in three chapters totaling eight pages. Briefly: Kimberly is caught in a snowstorm, cold, shivering, maybe lost, and certainly scared, until Mary, her five-year-old owner, finds her, brings her inside and sets her in a blanket before a roaring fire (Chapter One). Having been so cold and scared and now being so warm and comfortable (though possibly coming down with a cold—“meow-choo!”), Kimberly dozes off, only to be suddenly awakened by a large man in a red suit who leaves a mountain of gifts beneath the Christmas tree (Chapter Two—the dream sequence). In the morning, Kimberly awakens, surprised to discover not a mountain of gifts beneath the tree, but only a few, because Mary’s family is not rich. But Mary, far from disappointed, is so happy and grateful for what she has been given that Kimberly learns the true meaning of Christmas: It is not how much you get, but how much you love (Chapter Three).

However enthralled you may be with this brief summary of “A Kitty Kat Christmas,” let me assure you, it is a terrible, terrible story. I don’t think I wrote it to be terrible, but it is, undeniably and objectively, terrible. I have no recollection what any of my colleagues thought about it except one—the woman from the job placement agency whose interest in ancient Egyptian theosophy led her to imagine the possibility of squashing people with her thumb like ants. For reasons never clear to me, she appeared in the office one day as our new receptionist and remained so for the rest of my time there. Perhaps she had discovered that being a receptionist paid better than finding people jobs as receptionists, or perhaps her tendency to transform placement interviews into reflections on the theosophical insignificance of pedestrians had compelled her superiors to suggest she find a new line of work. To this day, I regret never asking what precipitated her career change.

As I left work the day after the office holiday lunch, she stopped me. “Dallas, I loved your story!” I thanked her and was about to move on

when she added, “You need to publish it here,” and showed me a copy of I Love Cats magazine. “You really think I should?” “Oh, yes, it’s exactly their kind of thing.” I read the magazine that night, and she was correct, “A Kitty Kat Christmas” was exactly their kind of thing.

The next day I mailed my story to the editor under my grandfather’s name, Percy Keegan. I received a response about a month later. “I have good news and bad news,” the editor of I Love Cats wrote. “We want to publish your story, but only Chapter Two. We will pay you $40.” I immediately accepted, although I did explain how this editorial decision undercut the true point of the story as Chapter Two, the dream sequence, merely sets the stage for the moral of the story (“It is not how much you get…etc.”), which only comes at the end of Chapter Three.

I also explained why, even though my name “really was” Percy Keegan, I needed them to sign the check to “Dallas Denery.” None of this received any response and, when the check arrived, it contained no additional correspondence. I was hardly surprised. This was the same company that published Quick and Easy Crochet—their plates were full.

I remained a legal secretary for about another year, even after most everyone else—lawyers and secretaries alike—were let go after the firm lost its major client. But my time there was coming to an end anyway. I had started studying Latin through an adult extension program as I contemplated going to graduate school to study medieval philosophy, with the goal of becoming a college professor. Unsurprisingly, being a college professor is not at all like being a legal

secretary. Among other things, instead of writing stories about cats discovering the true meaning of Christmas, you end up writing essays about writing stories about cats discovering the true meaning of Christmas. This, evidently, is what we mean by “scholarship.”

Professor of History and Associate Dean for Curriculum Dallas Denery II is an intellectual and religious historian who is interested in questions like “Why do we care about the past?” He has written a great deal about lying, including his most recent book, The Devil Wins: A History of Lying from the Garden of Eden to the Enlightenment, and—now—two pieces about kitty cats and Christmas.

To read the entire three chapters of Denery’s “A Kitty Kat Christmas,” visit bowdoin.edu/magazine.

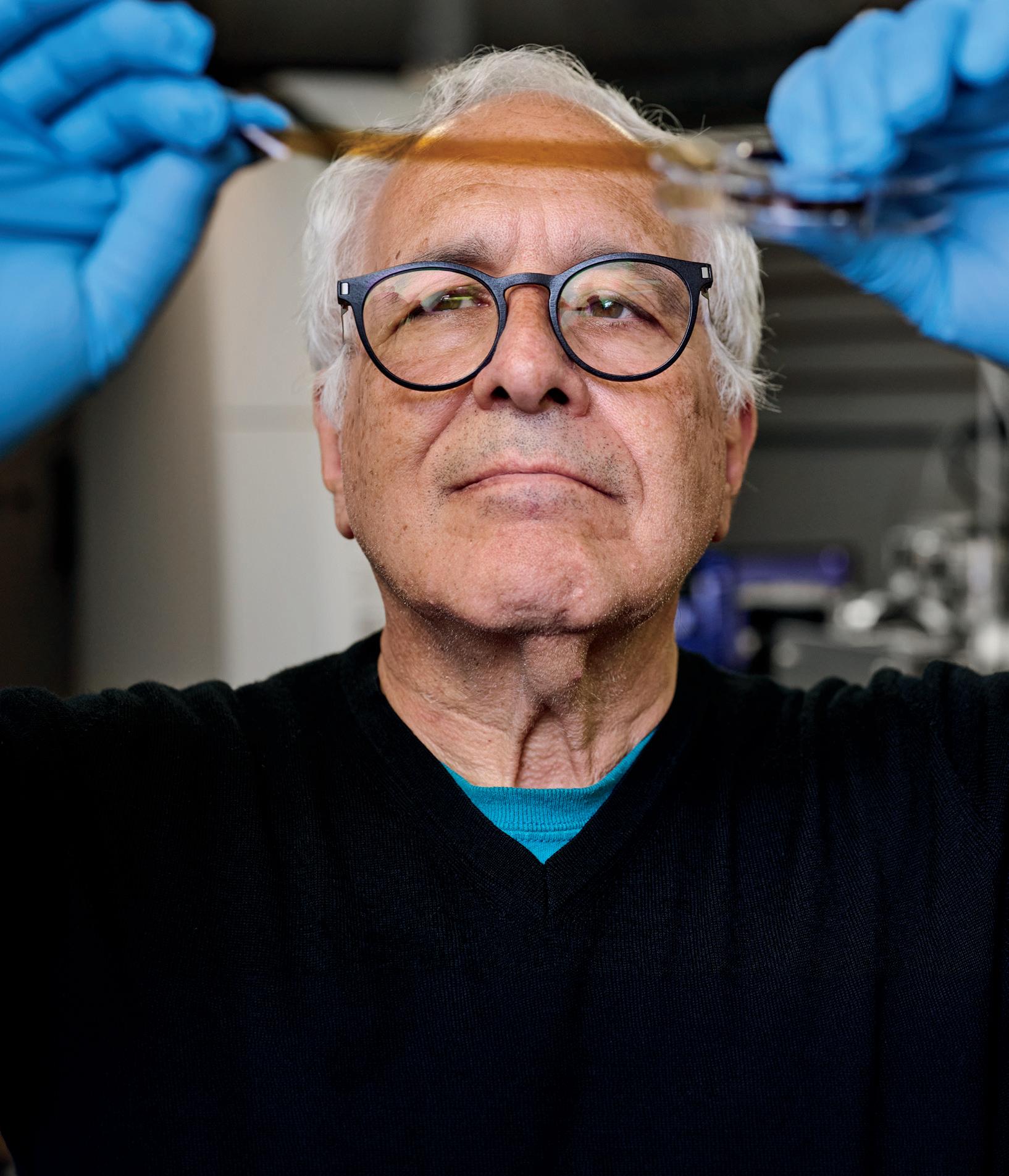

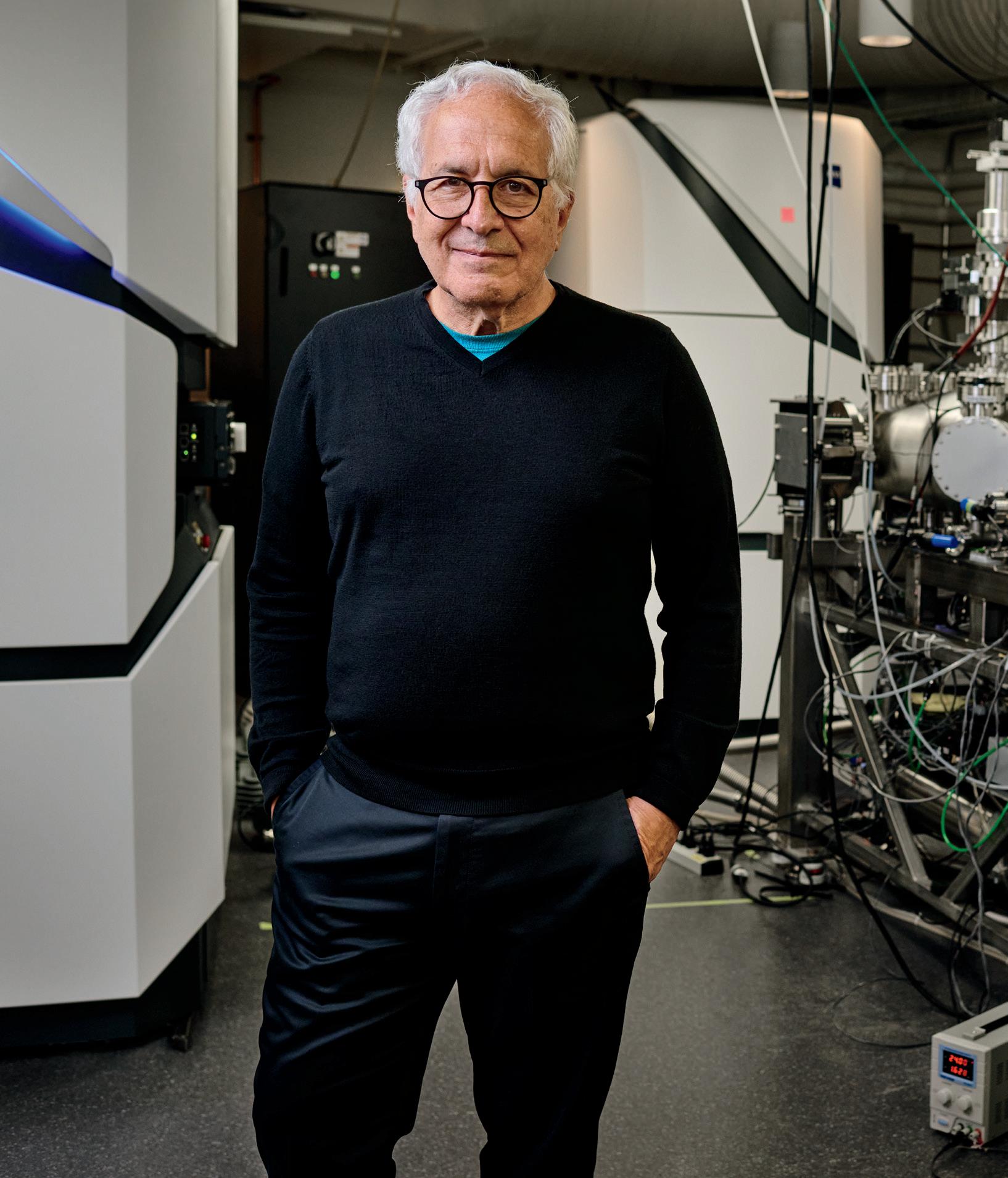

BY MICHAEL BLANDING PORTRAITS BY JARED LEEDS

B R A I N B O W

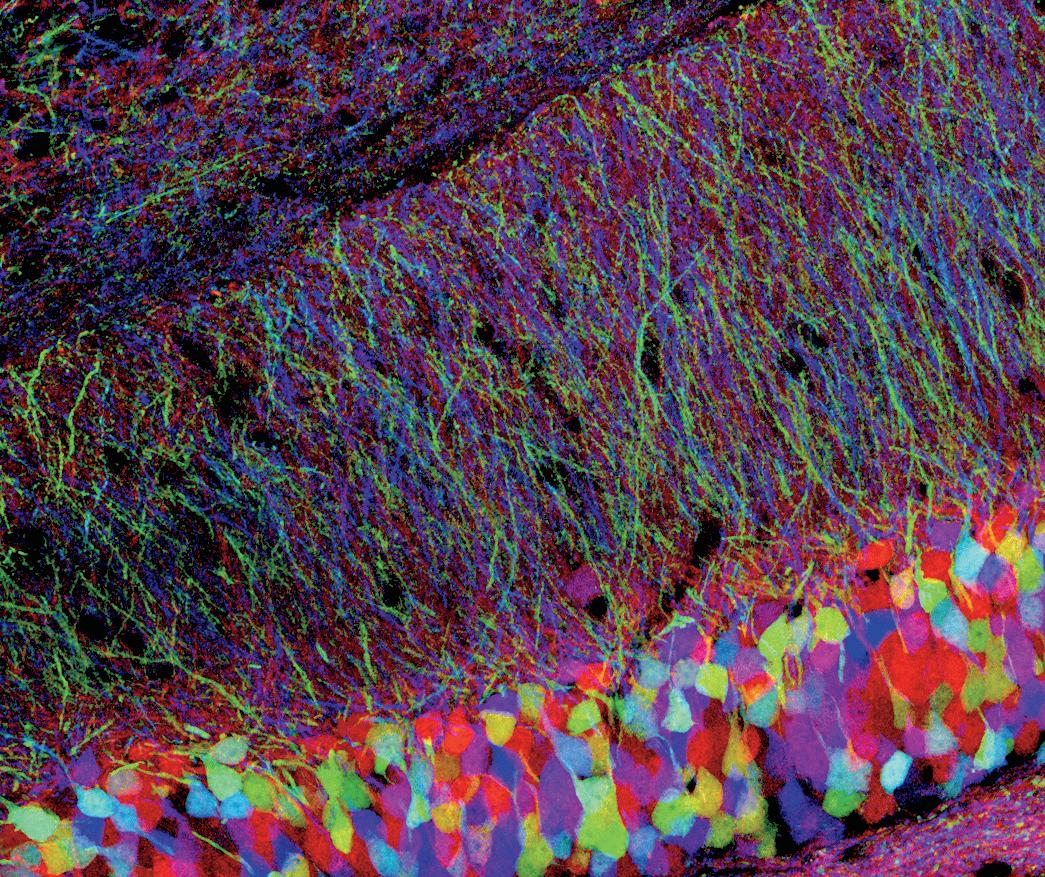

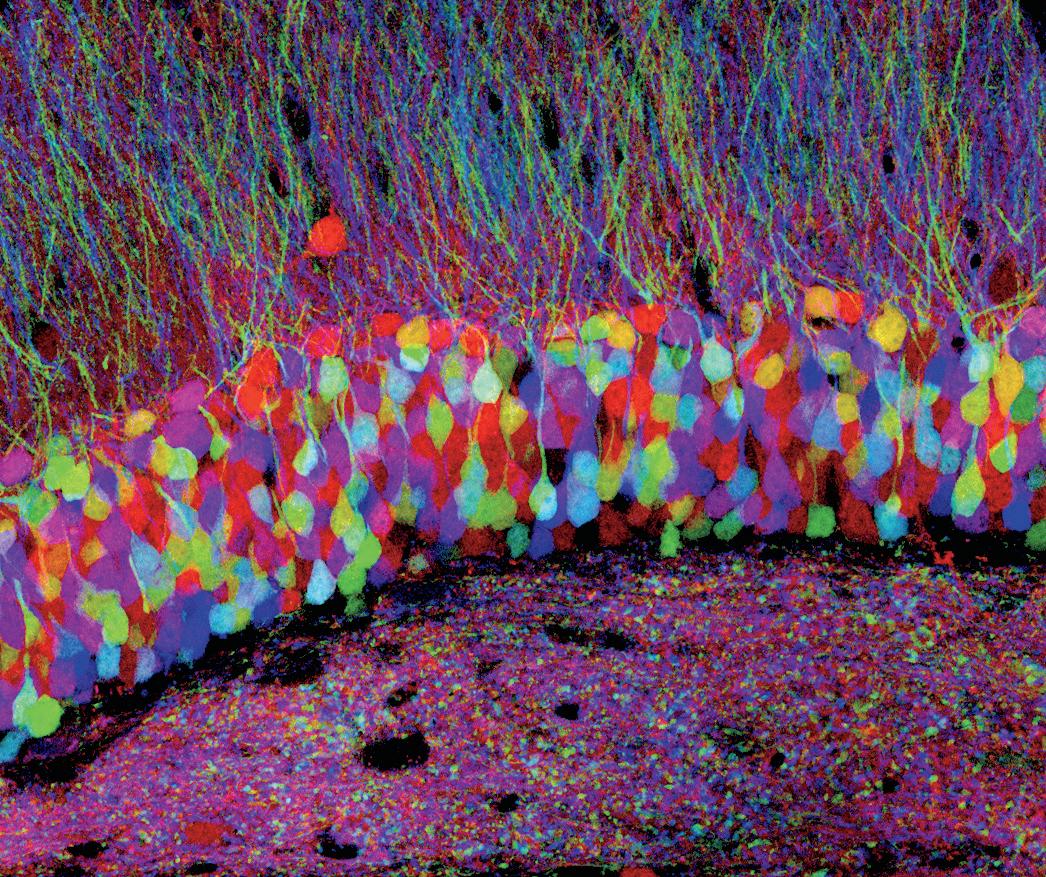

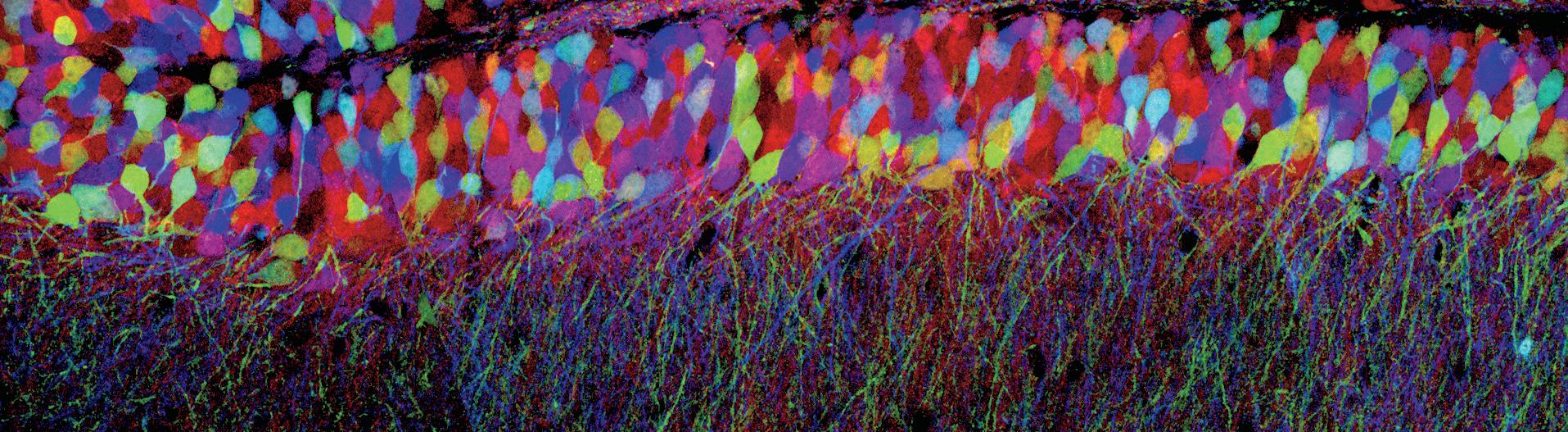

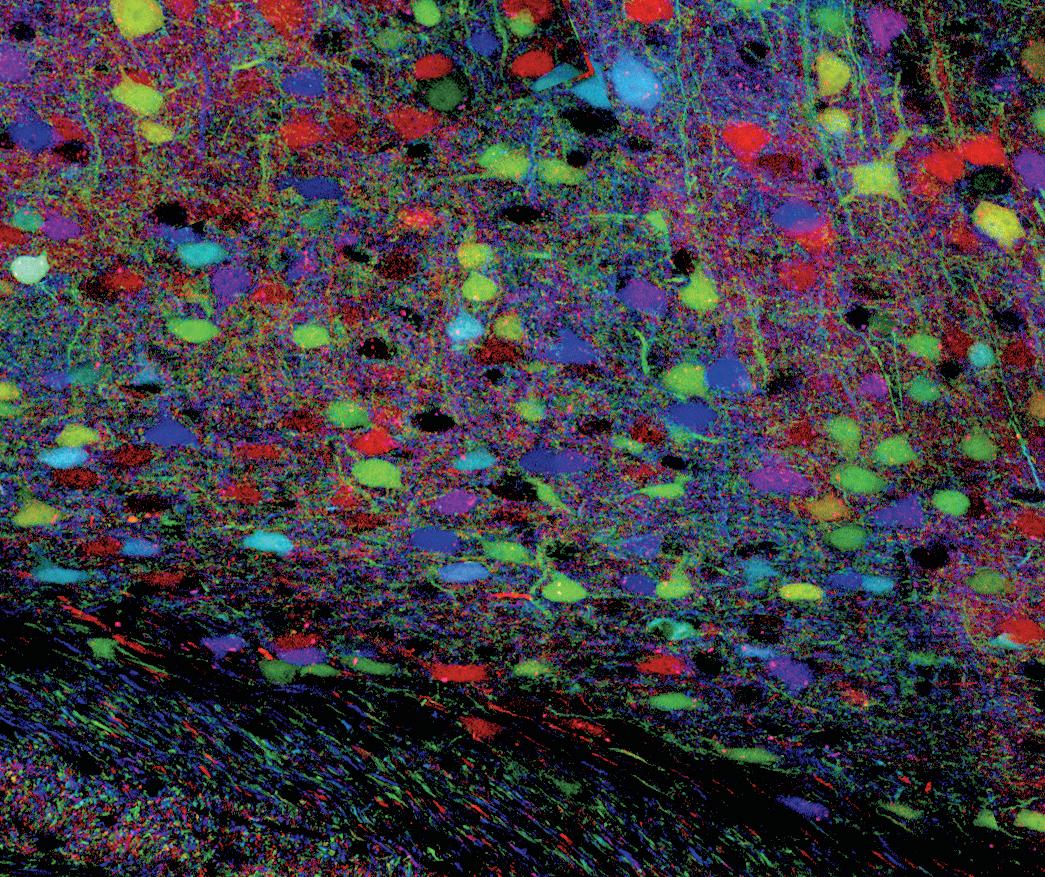

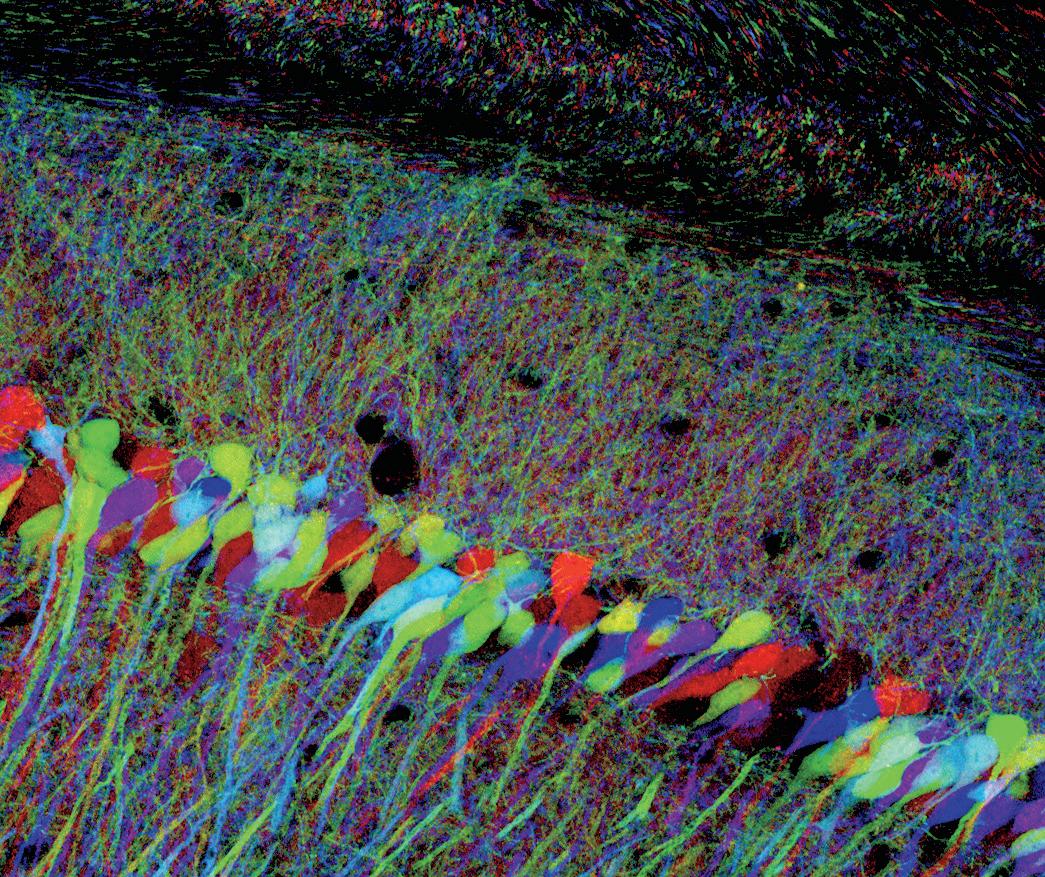

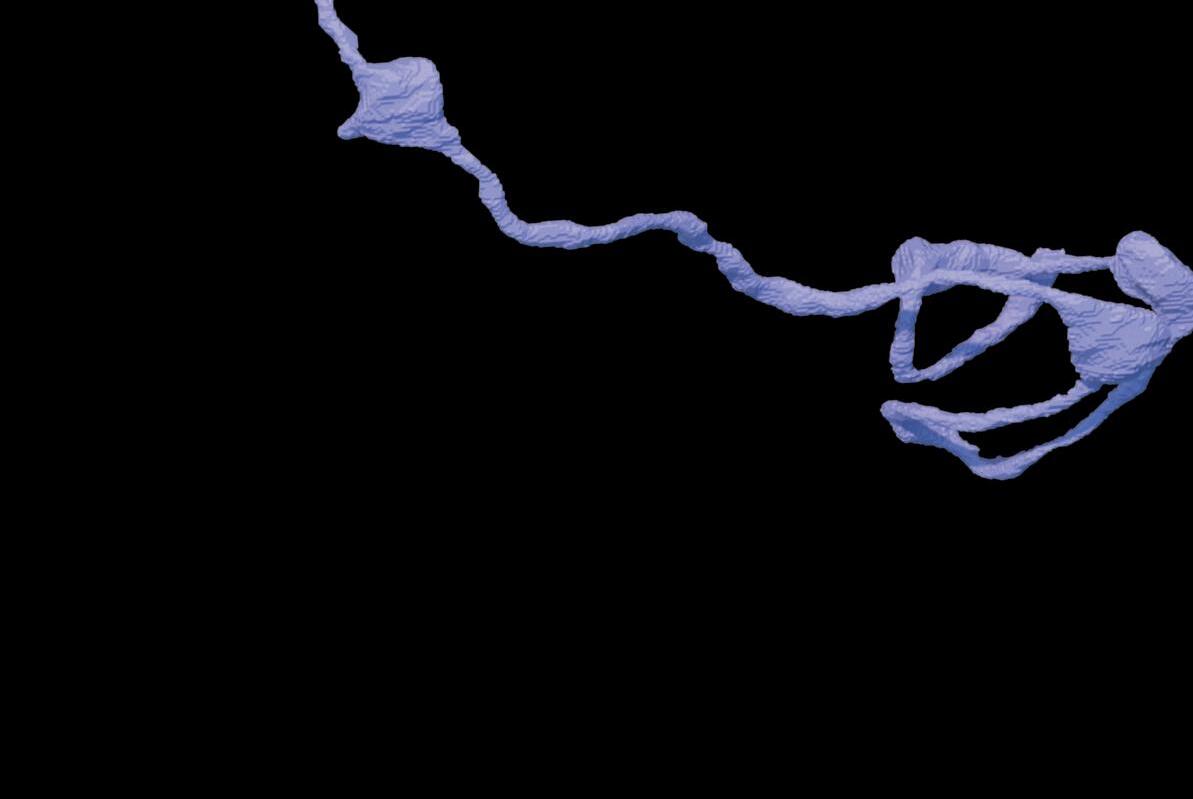

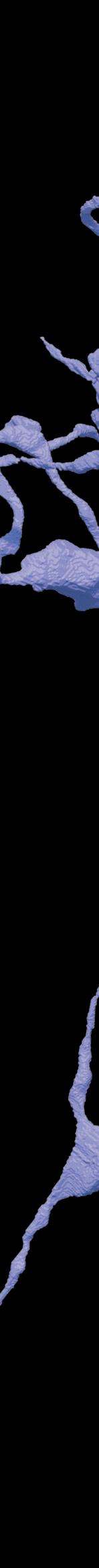

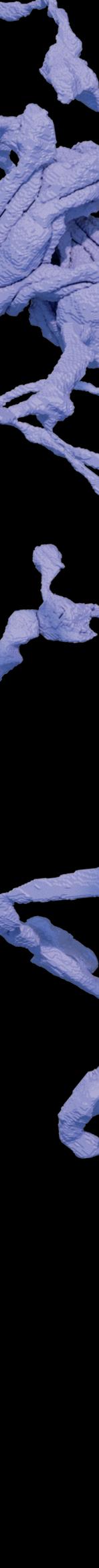

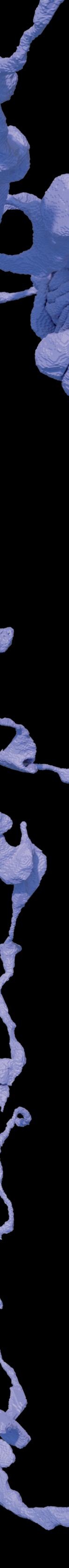

Opening spread:

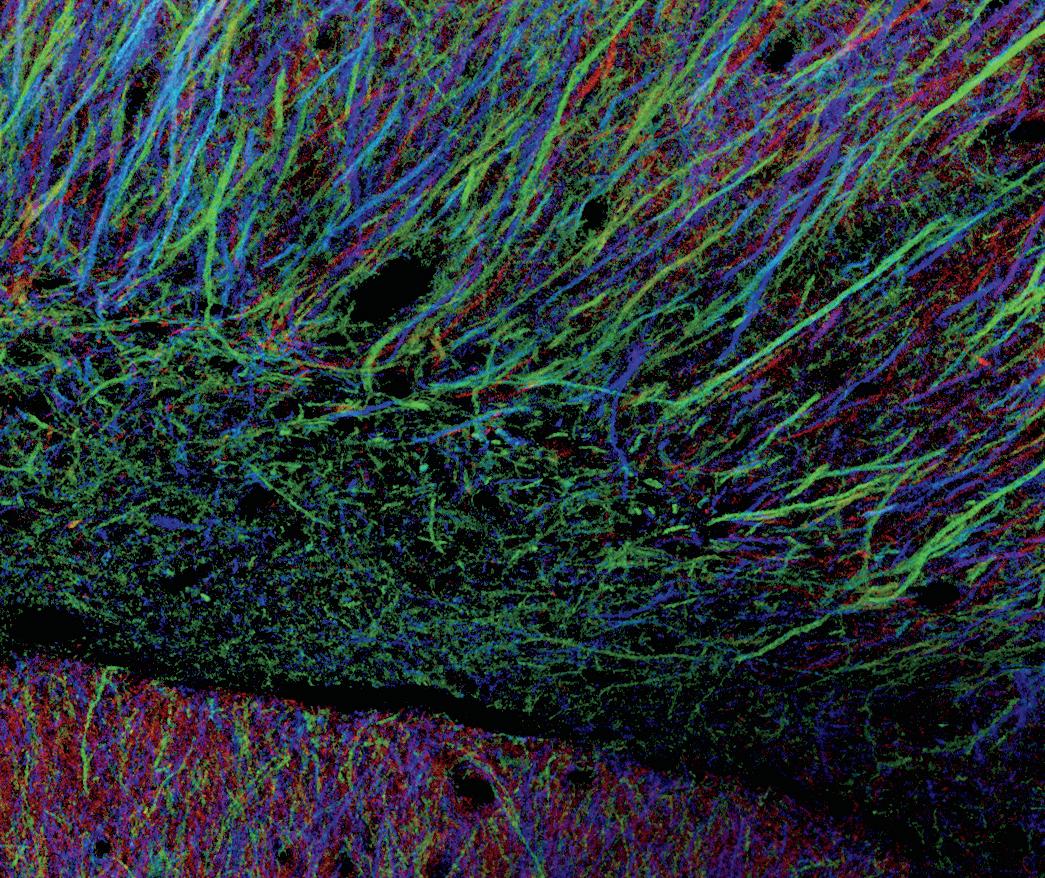

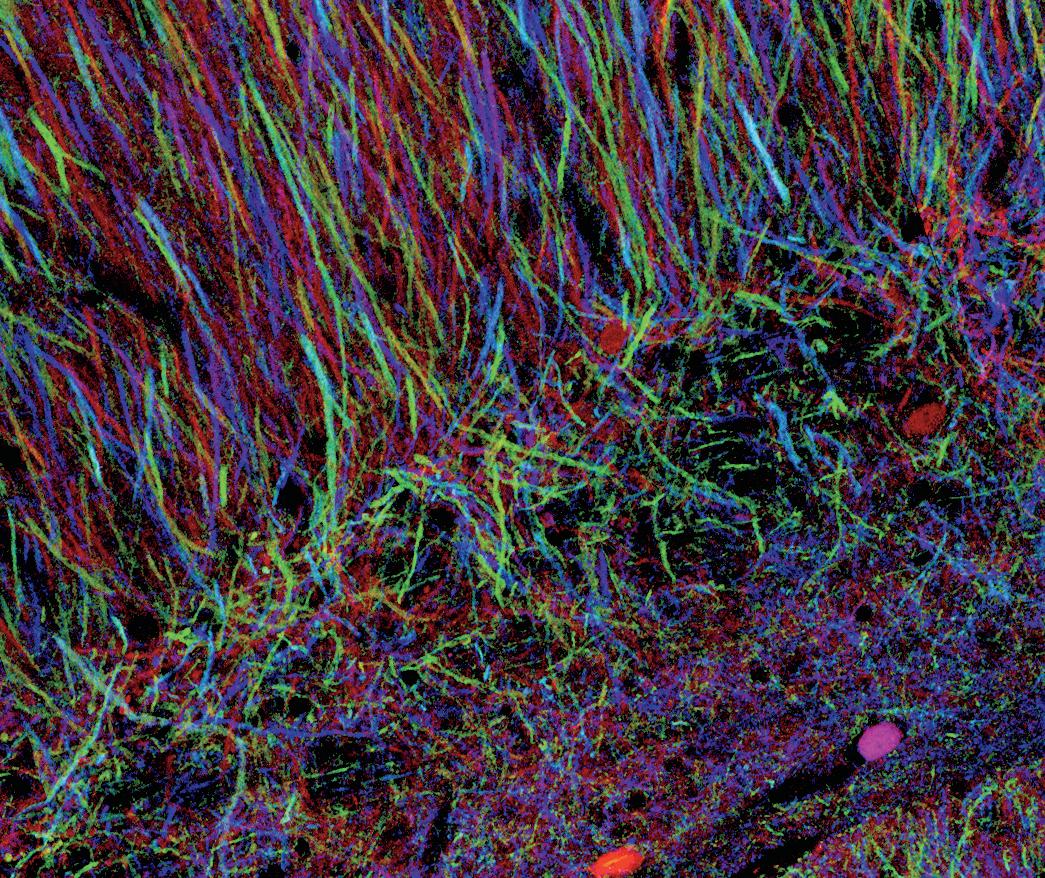

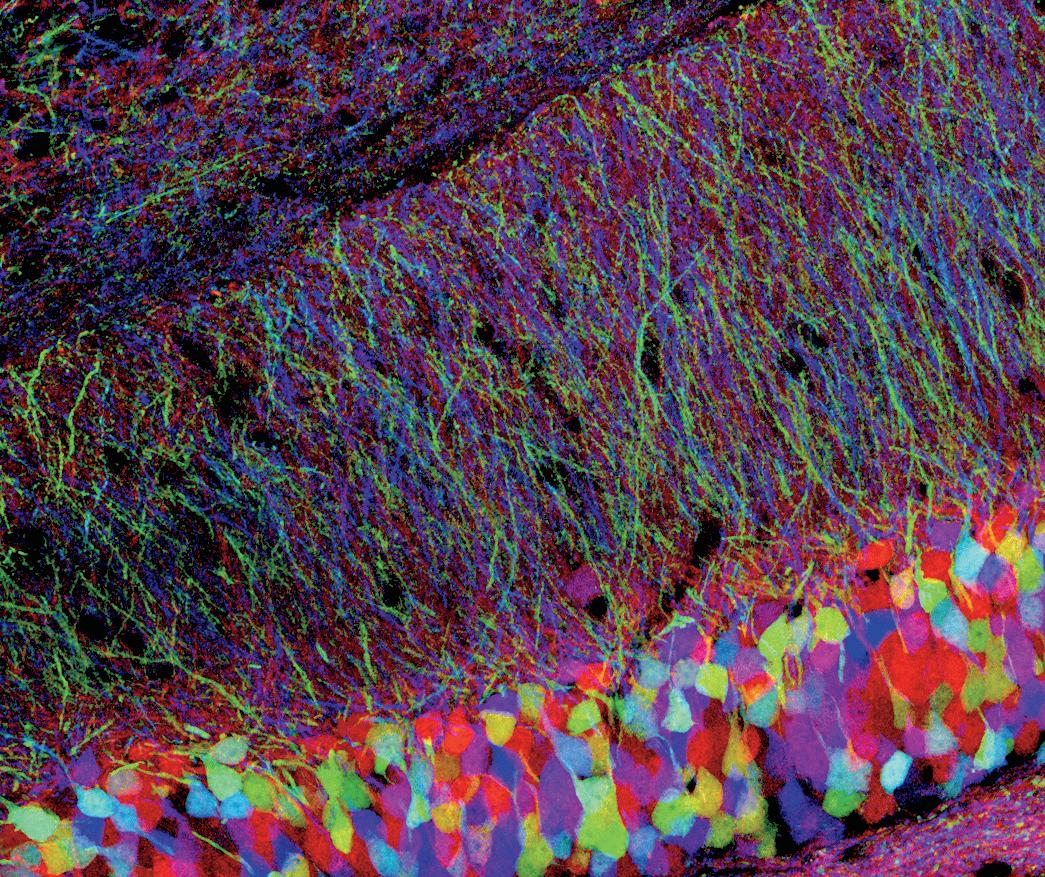

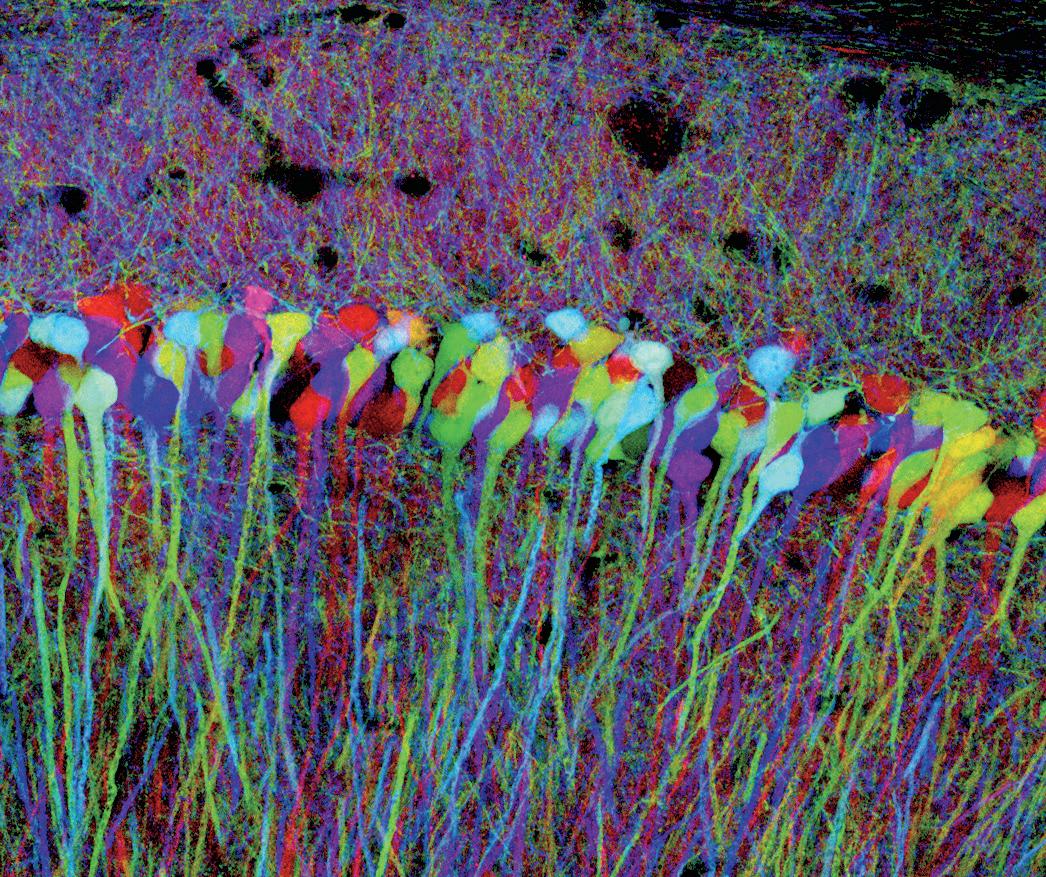

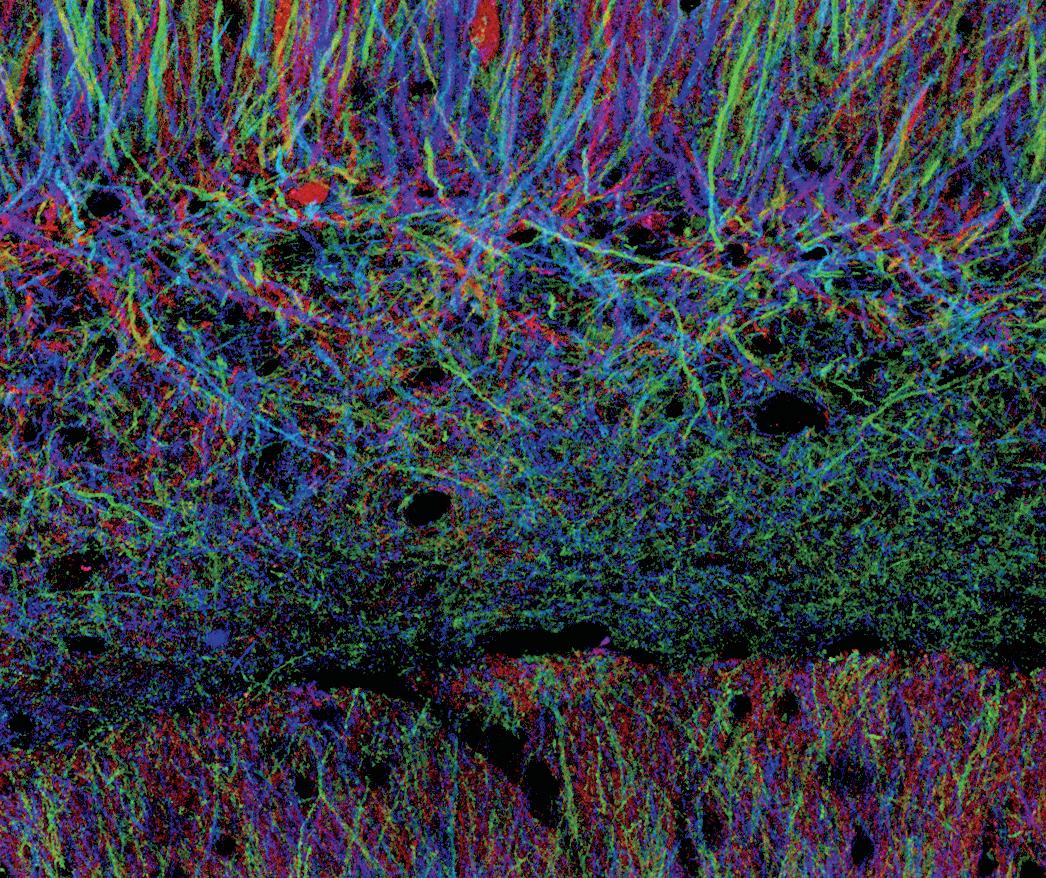

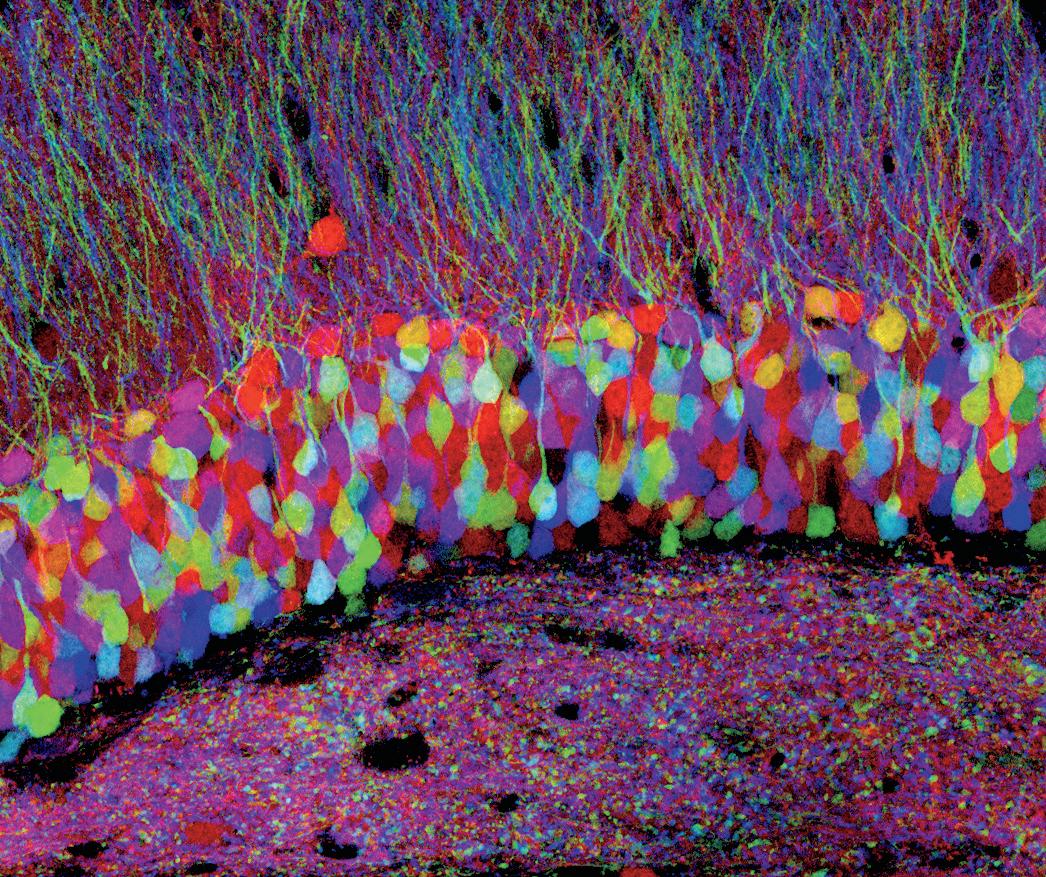

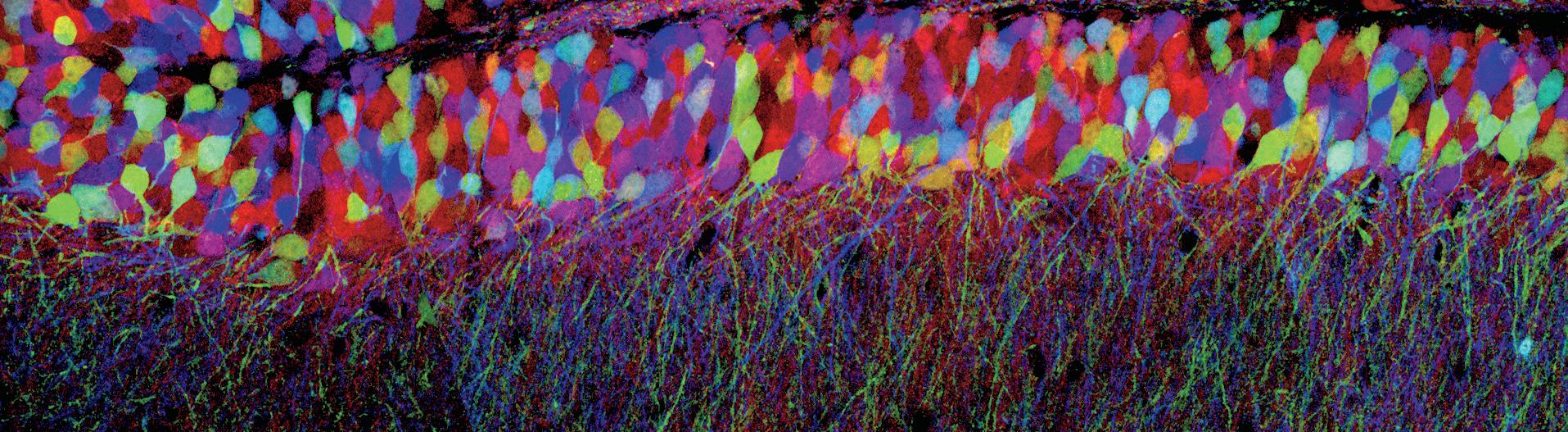

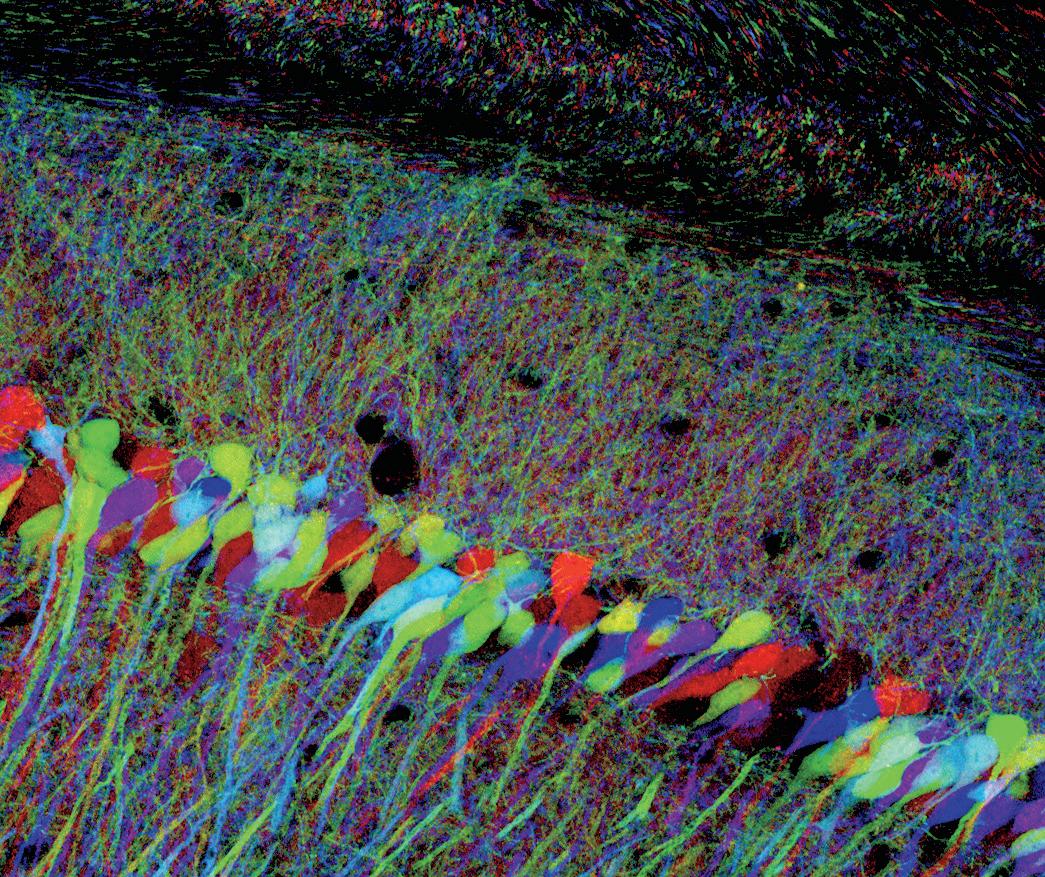

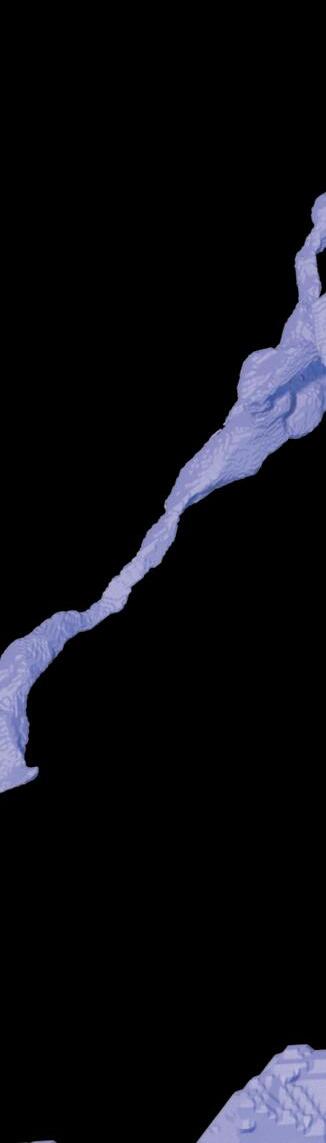

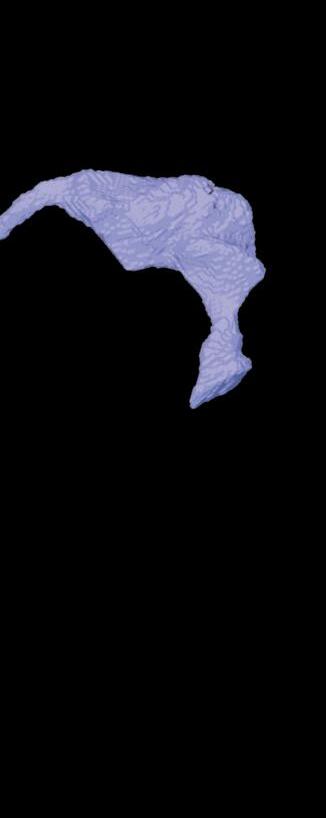

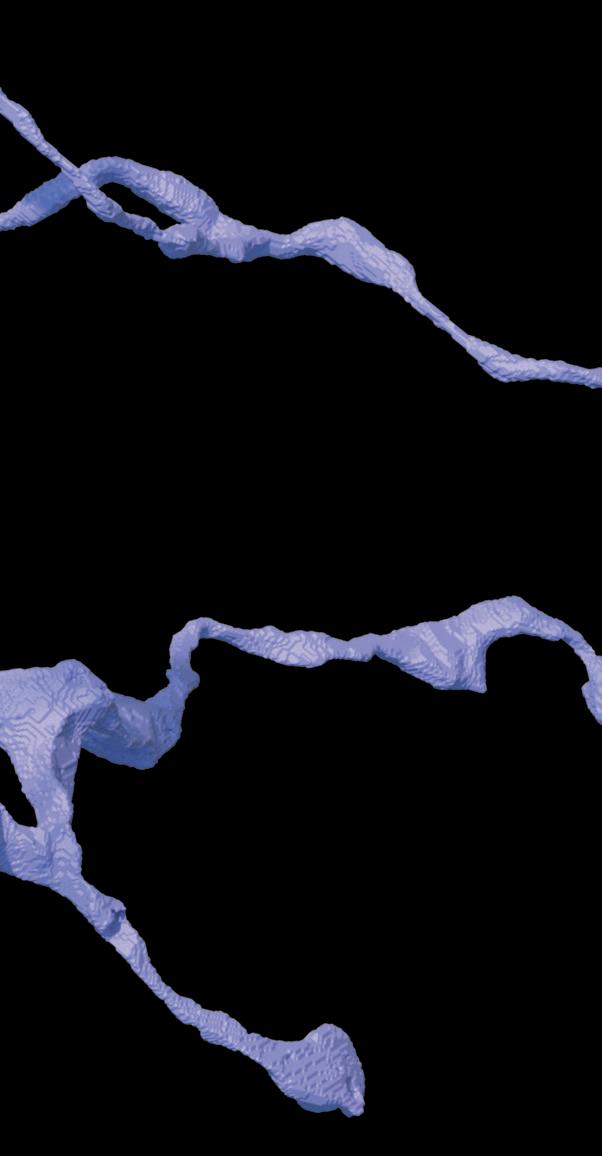

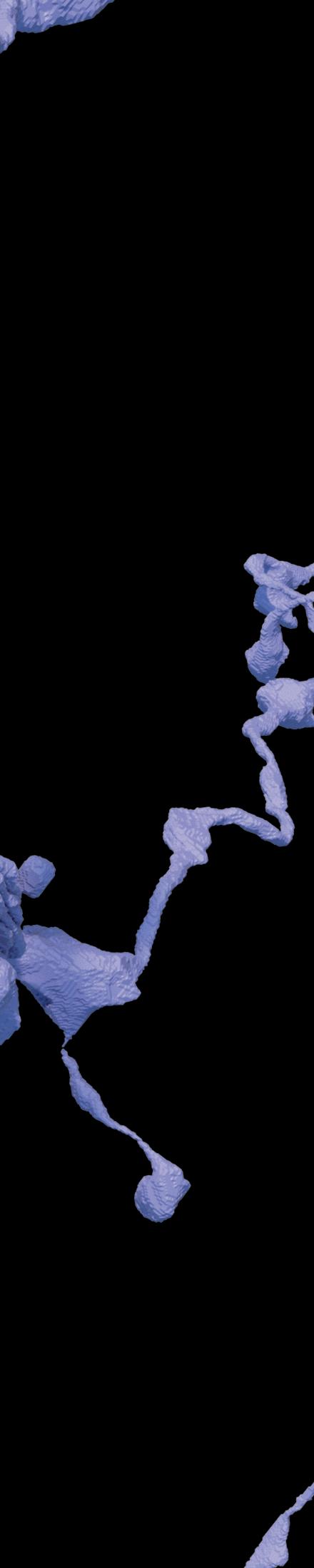

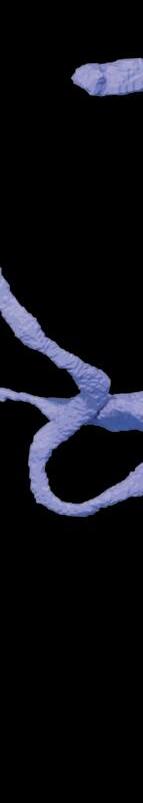

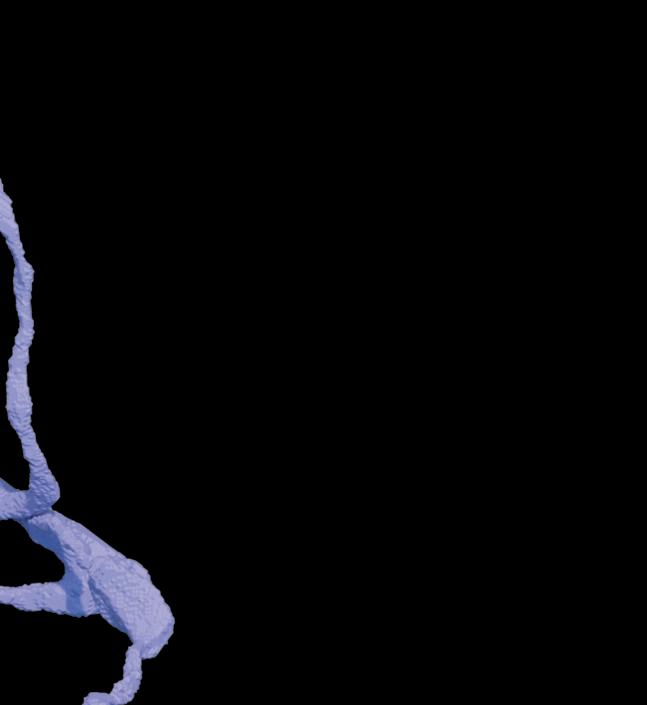

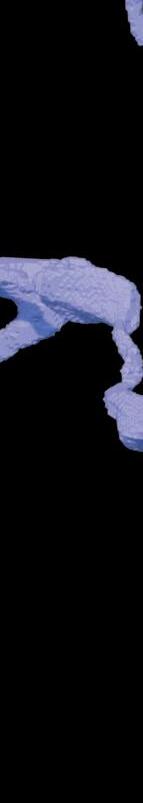

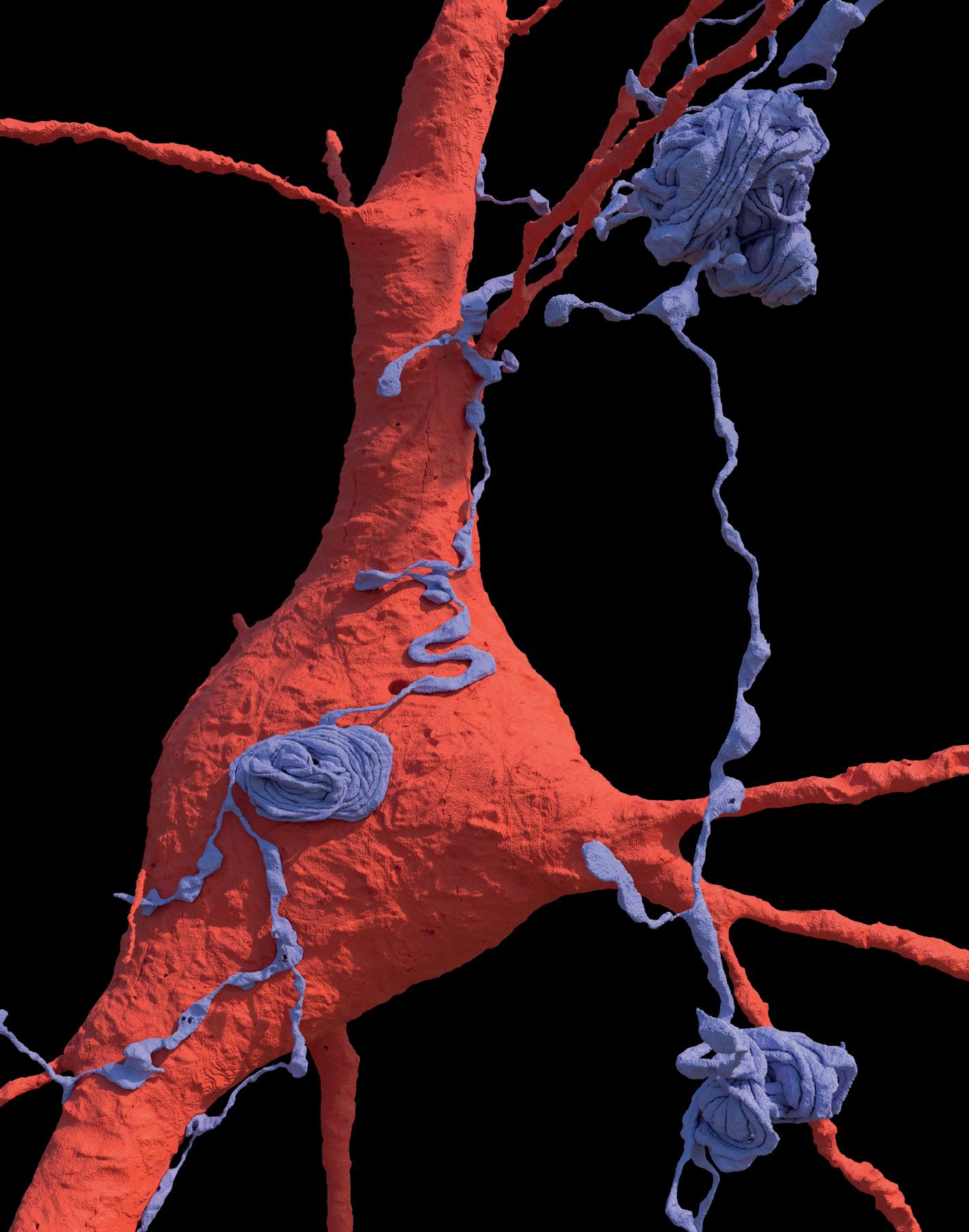

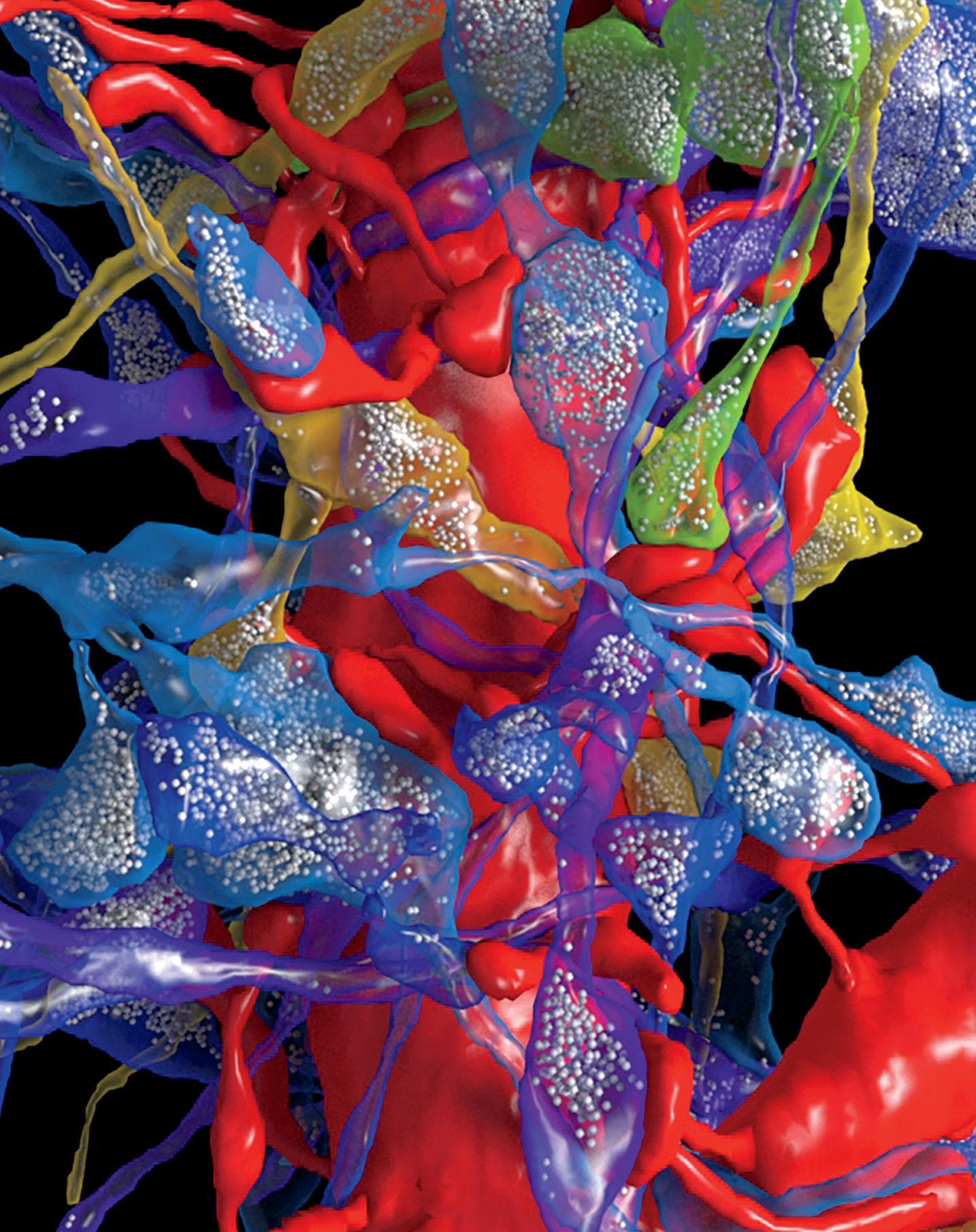

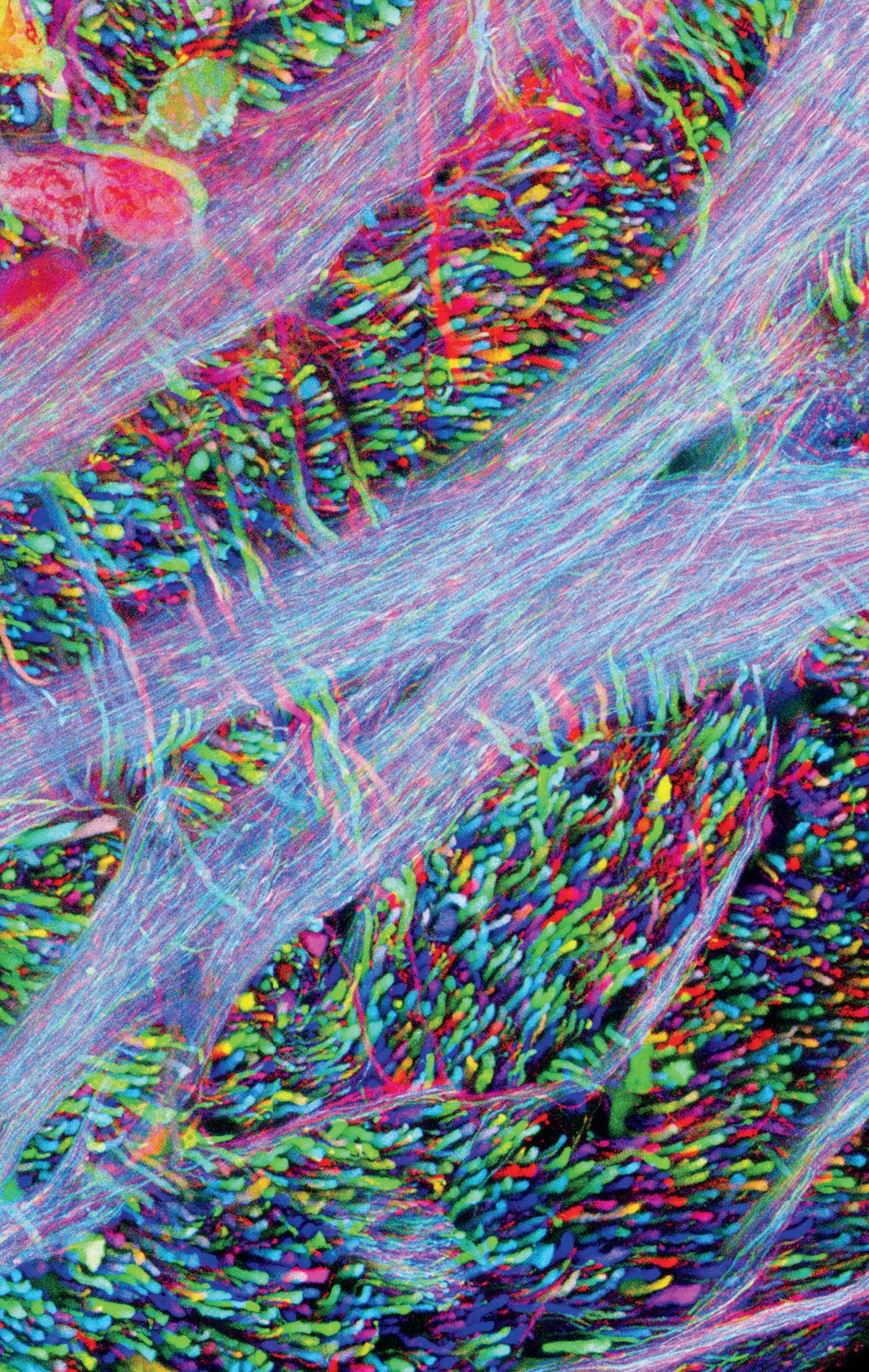

During their work to build a view into the human brain, Jeff Lichtman’s team discovered rare loops in some axons carrying signals away from the cell they called “whorls.”

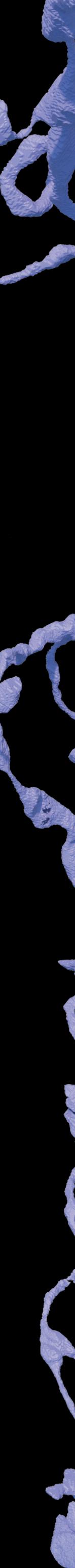

Opposite page:

Lichtman examines a piece of tape containing very thin slices of brain embedded in resin and arranged in a way that resembles a film strip.

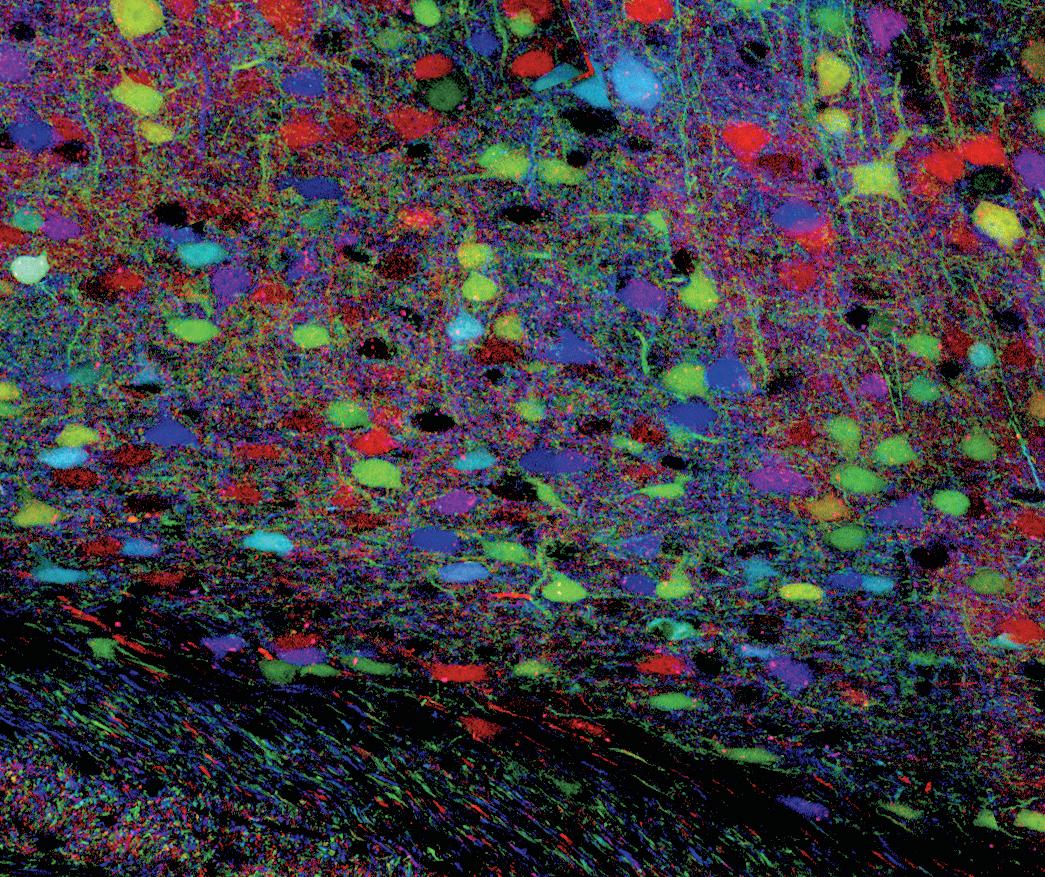

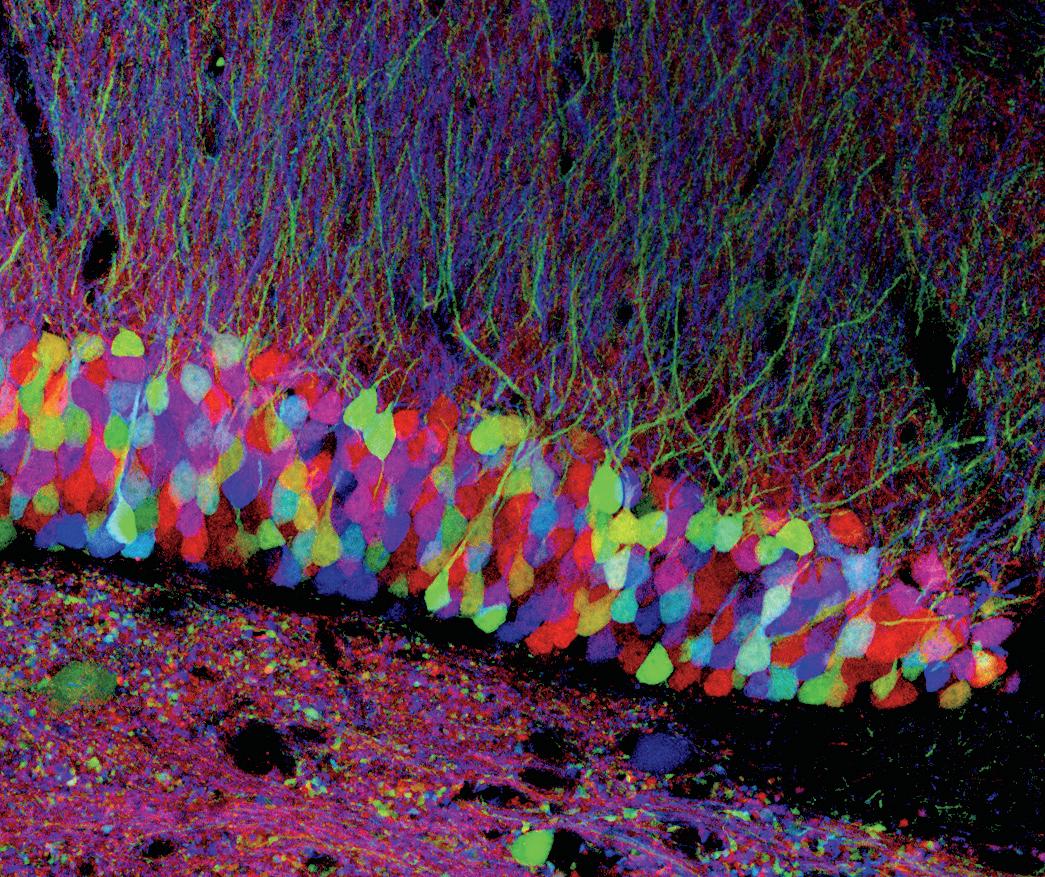

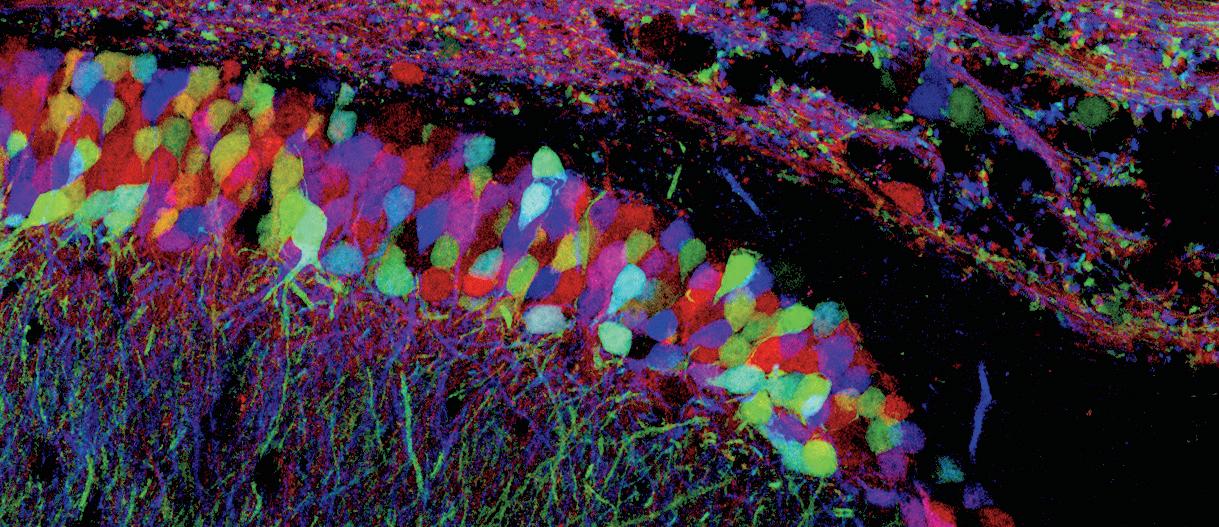

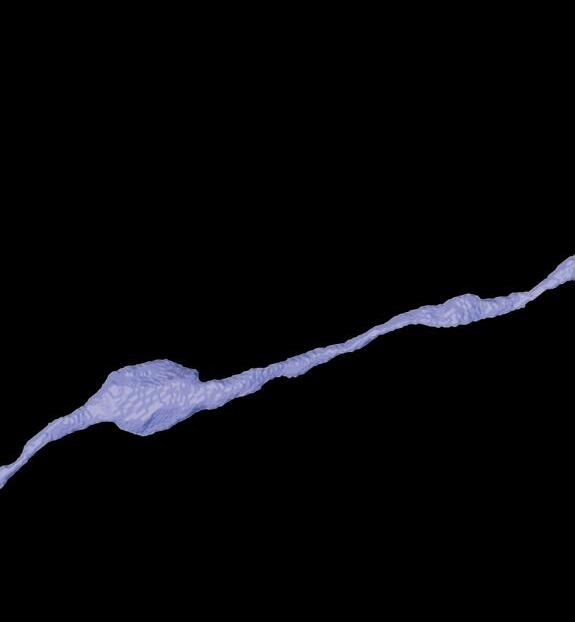

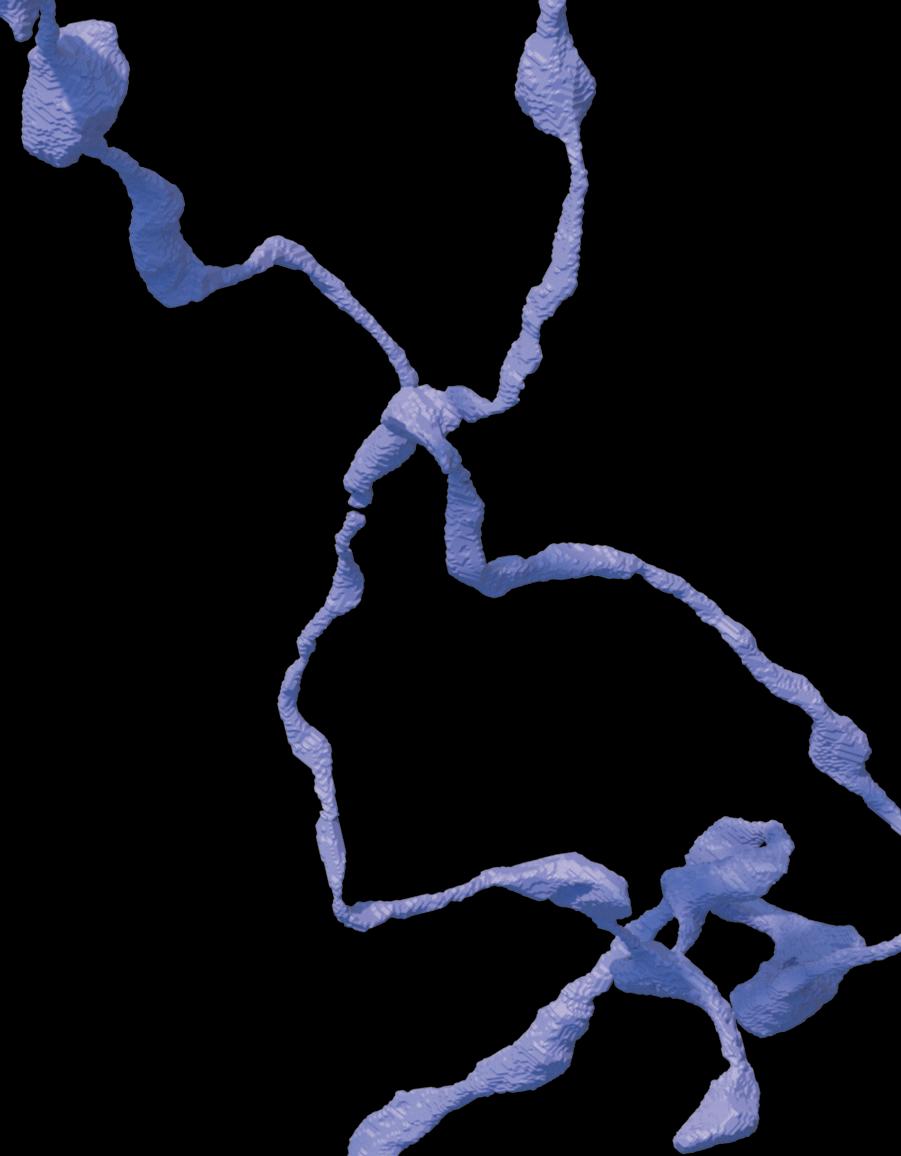

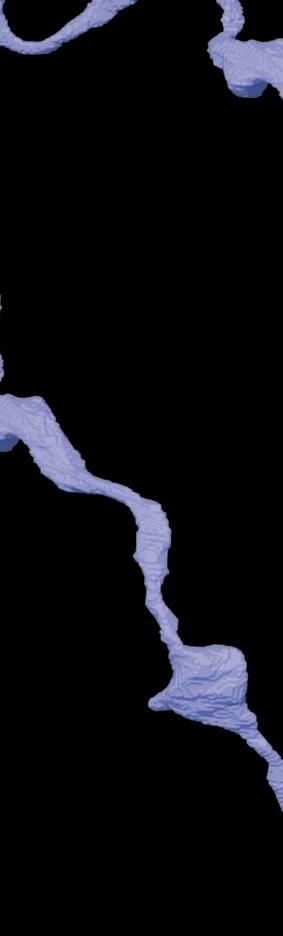

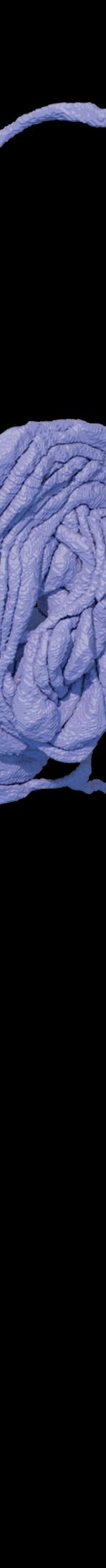

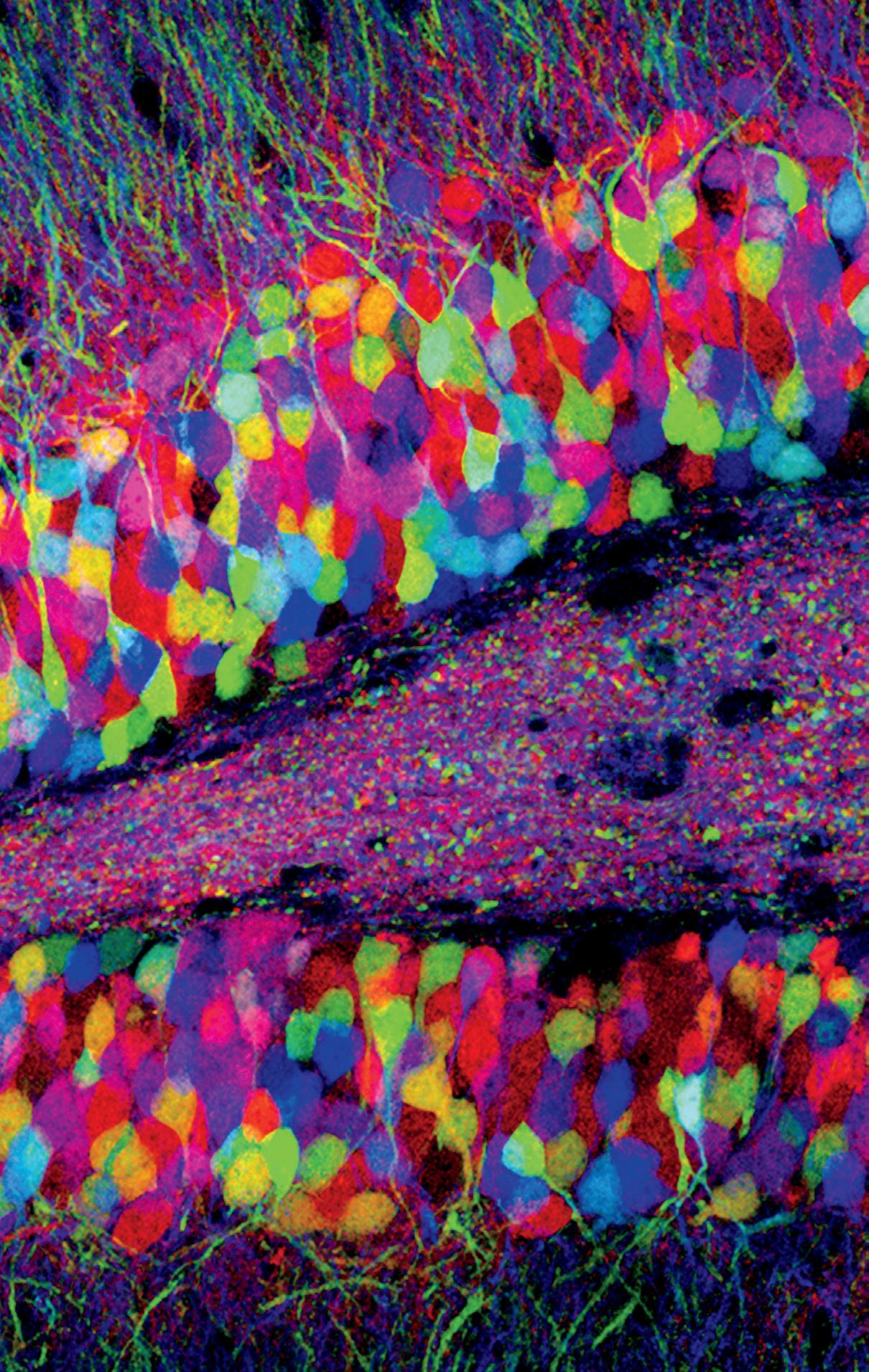

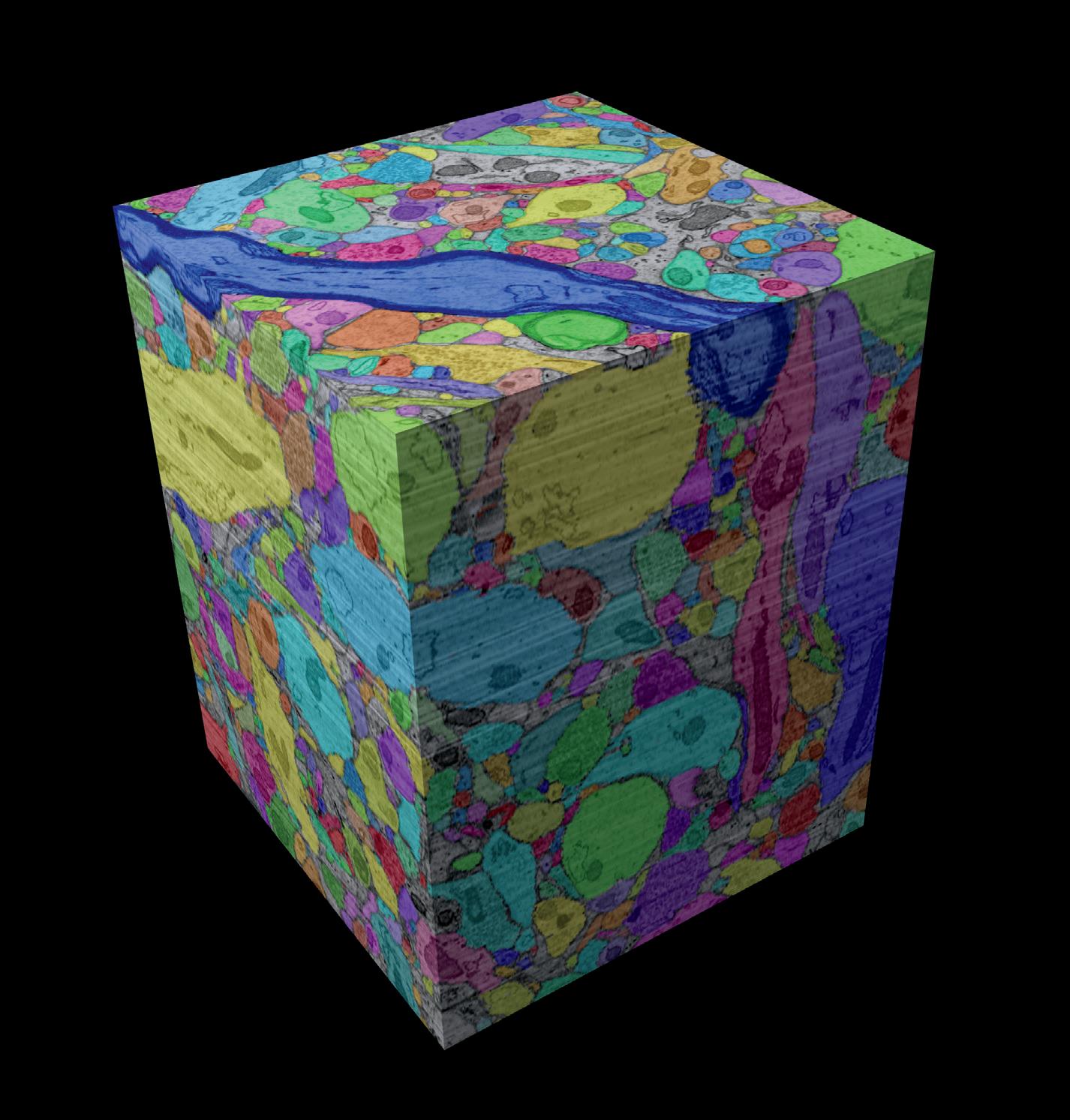

A Brainbow image showing different cells by color. In this innovative cell-labeling technique, hundreds of unique color profiles can be used as cellular identification tags.

“THINK OF AN AMERICAN FLAG,” says neuroscientist and Harvard professor of molecular and cellular biology Jeff Lichtman ’73, sitting in the office at his lab. In response, he says, you might envision a field of blue, speckled with fifty bright stars and laced with thirteen red and white stripes. “You’d have no trouble rendering that, and it doesn’t take a week—you render it instantaneously,” says Lichtman. “I could have asked you to render your mother, or your pet dog, or your child—it doesn’t matter, it’s there immediately.”

Easy—but here’s the hard part: Where in the brain is that memory sitting? “Is it a physical entity? Does it weigh something?” Lichtman asks. “It has to be something so stable that even if you’re not using that memory—sometimes for decades—it’s still there, just like it was yesterday.” We might imagine a vast file cabinet in the brain, with drawers labeled “American flag” and “mother” and files made up of proteins or other material waiting to be retrieved.

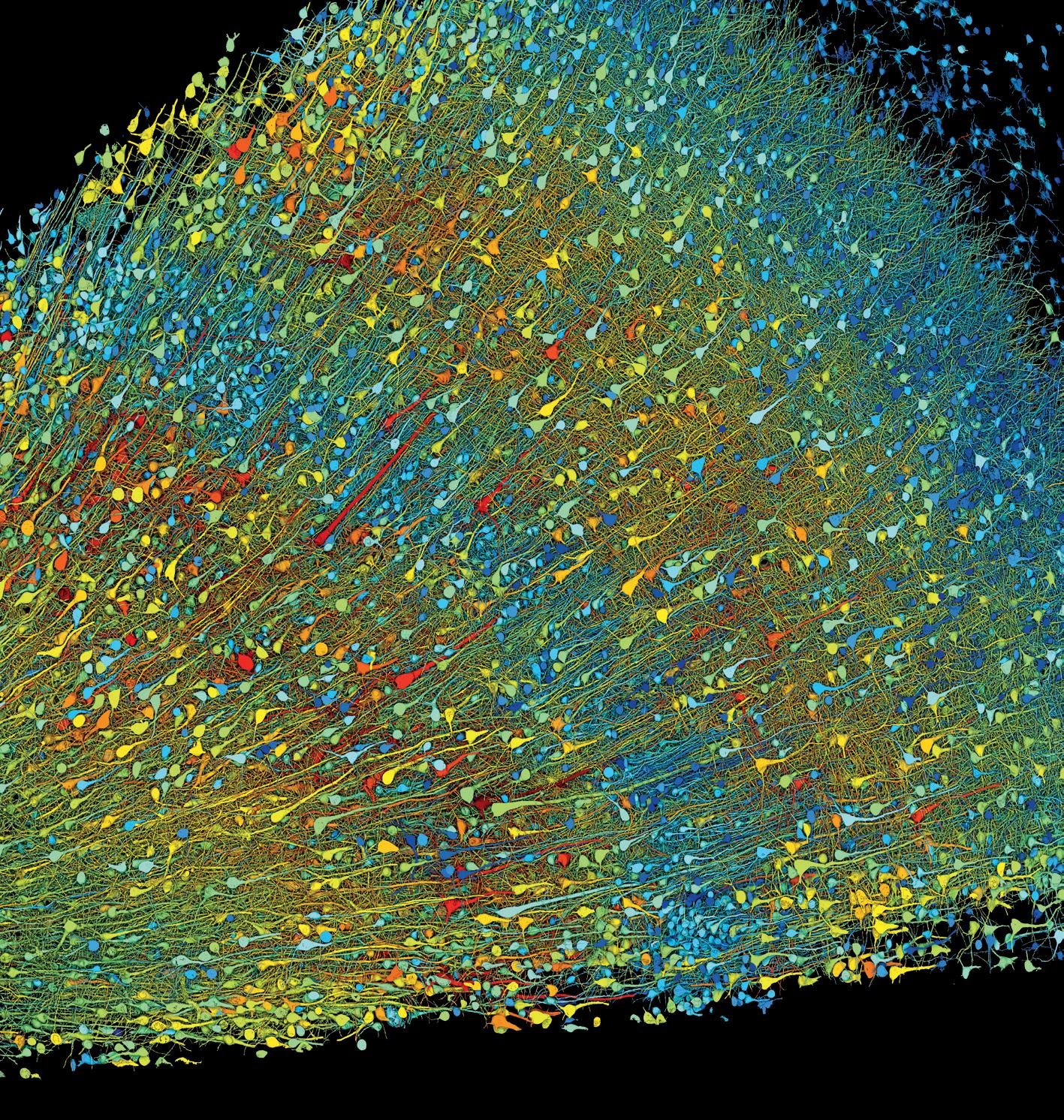

Lichtman has a different theory, on the forefront of brain science: that everything we know and learn is embedded not into any particular molecule, but rather in the connections between nerve cells. “Each memory is not a chemical, it’s a pathway through this vast morass of wires,” he says. “What’s being triggered is a movement of information through that wiring system in the brain.” While the Human Genome Project has mapped the genes in the body and examined their functions, Lichtman believes that when it comes to the brain, genes are not as important as cells and how they are connected. He’s spearheaded an ambitious project to map the brain that he’s dubbed the “connectome,” tracing the millions of miles of neurons packed into that relatively small space to understand how people learn and remember, as well as why sometimes the wiring goes wrong. Last year, Lichtman was appointed dean of science for Harvard’s Faculty of Arts and Sciences. A week later, he and his lab colleagues published a landmark paper in Science announcing the largest image of the brain to date: a digital three-dimensional rendering of a cubic millimeter of human brain tissue that contains 57,000 cells with 150 million synapses between them—1,400 terabytes of data in all.

The scale of the image is staggering. “Words fail us, not because we’re so emotionally overcome, but because the complexity of the wiring diagram cannot be put into sentences,” he says. “It’s like trying to describe all of New York City—even if you had a complete map of every single thing going on, words would not be able to capture it.” To overcome those limitations, Lichtman has developed innovative techniques to depict the brain visually, including a collaboration with Google using artificial intelligence to color tiny cells and parts of cells within. Already, the techniques have revealed never-before-seen structures with the potential to revolutionize brain science. There’s no telling what he might find on the way to his ultimate goal of mapping the complexity of the brain in its entirety.

When Lichtman was a kid growing up in Westchester, New York, his father did something early on that transformed his son’s life. A hematologist at a nearby hospital, he placed his old Leica medical-school microscope in the bedroom Lichtman shared with his brother. “I don’t remember him giving us any instructions, but I used it to look at everything—throughout my childhood, there was no aspect that wasn’t scrutinized.” He remembers keeping a Tupperware container of smelly pond water in the bedroom, spending hours watching paramecia and other protozoa swimming around “a whole gigantic world.”

Even now, a microscope sits on the desk in his sunny office, and Lichtman uses it regularly to illustrate points to students. “I actually can’t imagine an office without a microscope.” At Bowdoin, he aspired at first to be a writer or musician, but science was effortless when those subjects were not. “Biology was just a natural for me,” he says. “The advice I give to young people now is to choose what you find easiest—because if you keep pushing on what you find easy, you are going to get to a point where you find it hard, and by then, not many people will be at your level.”

Lichtman took his own advice, going into an MD/PhD program at Washington University in Saint Louis. Still, the liberal arts environment

in his undergraduate years not only shaped his career but also influenced his thinking. “I give Bowdoin a lot of credit for encouraging that liberal arts worldview, where you are really not a complete human being if all you do is advanced math or electronics,” he says, recalling evenings at professors’ houses and long conversations over dinner that blurred the line between classroom and life.

“He is a true philosopher of science,” says Bobby Kasthuri, a former student at Washington University and longtime collaborator. “Jeff is a natural contrarian, but there’s a kind of gentleness to his contrarian nature.

He’ll talk about radical ideas but in a laid-back fashion.” With the rise of molecular biology, neuroscientists increasingly looked to explain cellular behavior through genes and the molecules they produce, developing a theory that pathways were strengthened in the brain through the transmission of chemicals between synapses. Lichtman, by contrast, developed a belief that it wasn’t chemicals as much as the physical structure of the brain that determines its function.

“Jeff has long argued that it’s very hard to go from molecules to behavior,” says Kasthuri. “His argument is that cells are the fundamental

The techniques have revealed never-before-seen structures with the potential to revolutionize brain science.

units. The way they connect is what really matters.” That view reshapes how we think about the brain and how it develops. Most people assume that our brains get more complex as we age, accumulating connections, but Lichtman sees it differently. “You are not building a wiring system as you get older, you are sculpting one,” he says. “You start out with wires for everything, and you ultimately keep the things you learn and get rid of the rest.”

As we prune connections, he says, older people literally get set in their ways. “They would call it wisdom,” he says. “You might call it being stuck in the past.” The process carries broad implications—psychologically, sociologically, even politically. “Different adults can see the same thing in radically different ways,” Lichtman says. “That is because they’ve developed different pathways based on what they’ve read, heard, and thought about. It becomes very hard to change that.”

On the other hand, he says, humans’ ability to change their brain wiring has made them uniquely resilient and adaptable as a species. “There was a time when humans didn’t live indoors or wear clothes,” Lichtman says. “We certainly didn’t read or write. Now we are not only able to encode information in our brains but also pass it along to others. That means

humans keep changing because of this profound ability to adapt our wiring diagrams to the world we live in.”

The same adaptability can also have a darker side, helping explain some forms of mental illness. Children raised in a dysfunctional or abusive home might adapt in ways that lead to emotional and behavioral problems or addiction. Other diseases, such as Alzheimer’s and epilepsy, seem to have a genetic component as well. Decades of attempts to pin those conditions on a single gene, or even a combination of genes, have failed. Lichtman speculates that in reality the causes are more complicated, stemming from problems that grow out of a miswiring in the diagram of the brain. “And until now, seeing that diagram has been impossible.”

in mapping how nerves connect, laying the groundwork for the new field of connectomics. After earning his MD/PhD in 1980, he became a professor at Washington for two and a half decades before moving to Harvard in 2004. At first, he used physiological techniques to stimulate nerve cells to determine which were connected. Nerve cells, or neurons, consist of a long spine called a dendrite, ending in a spiky structure called an axon, which connects to other nerve cells across small gaps called synapses.

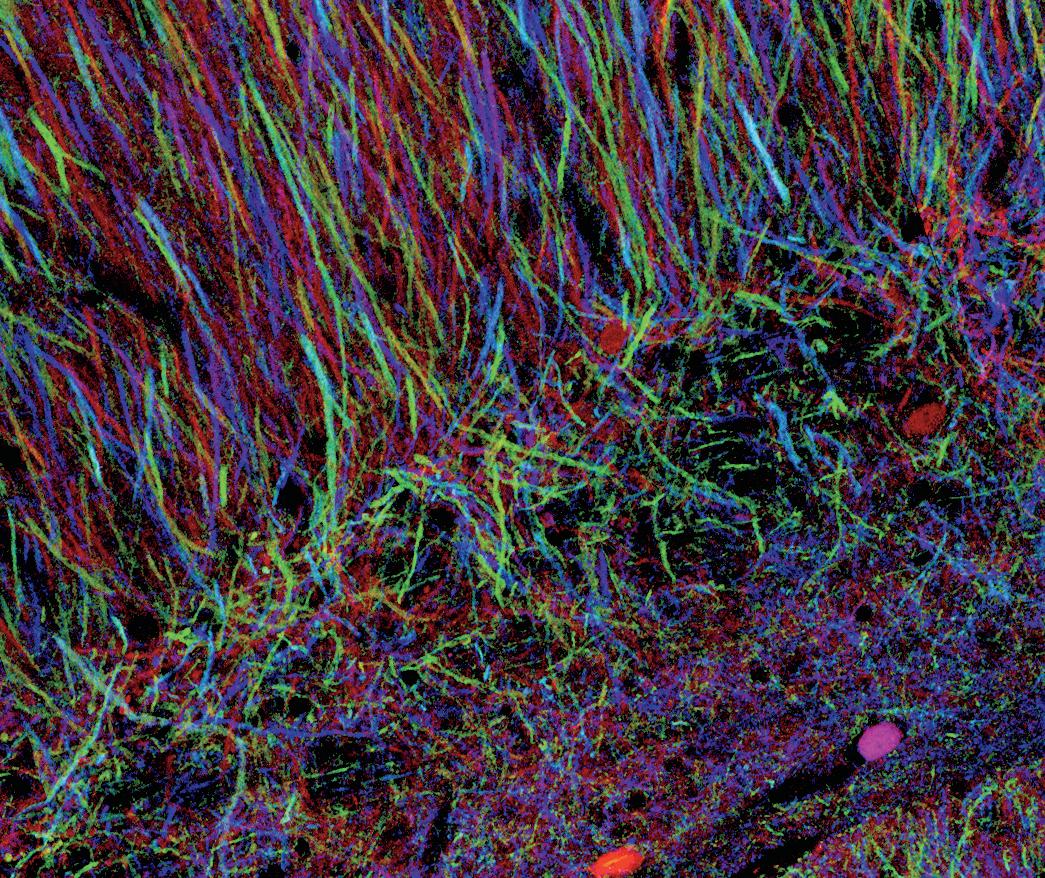

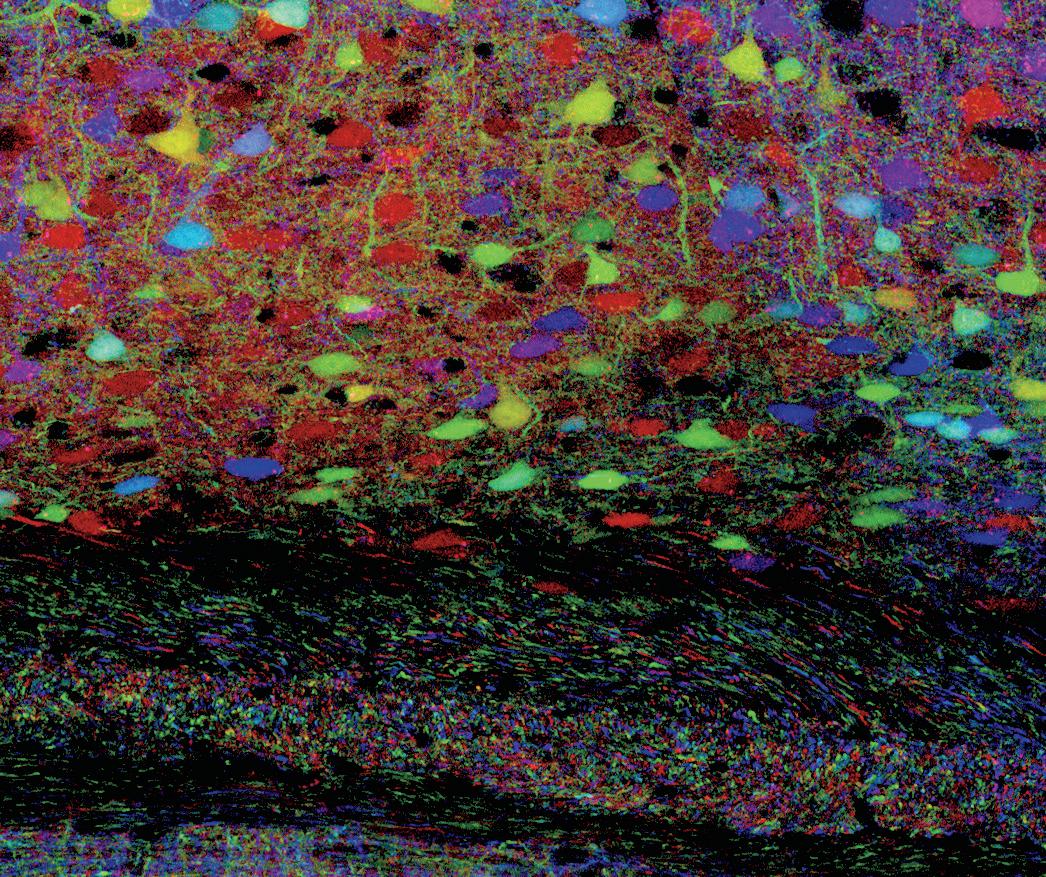

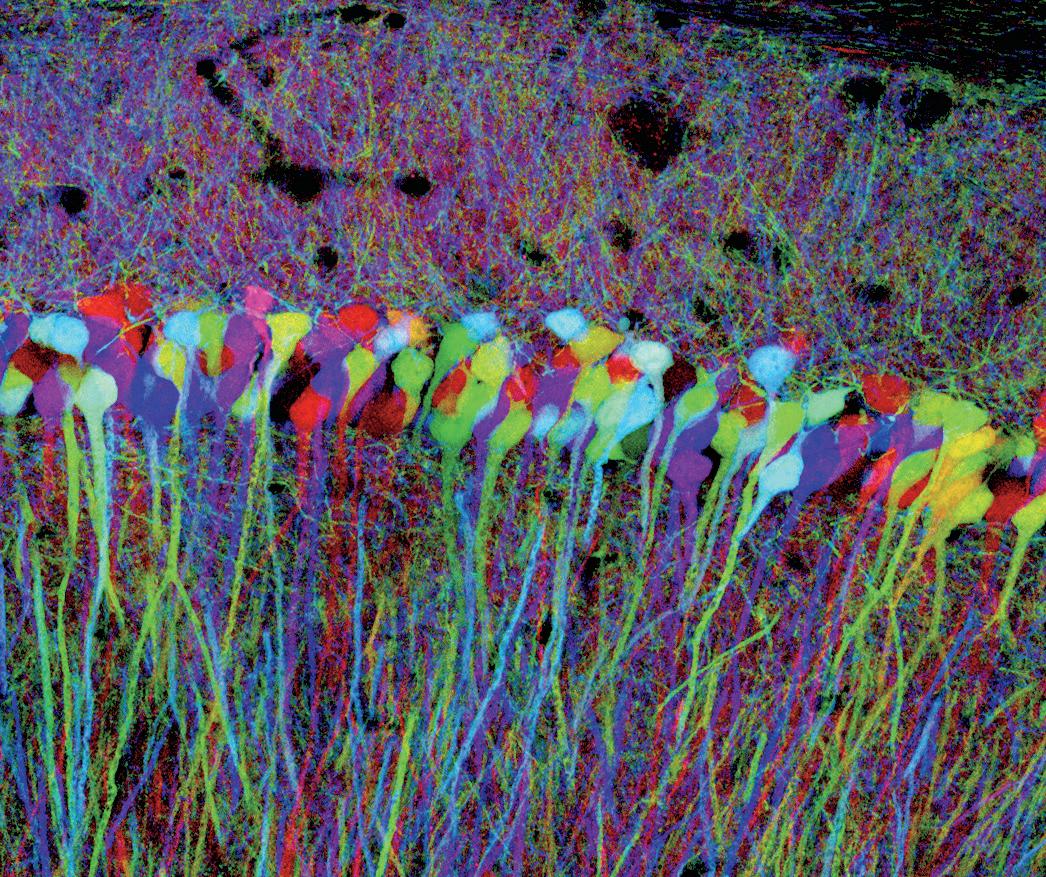

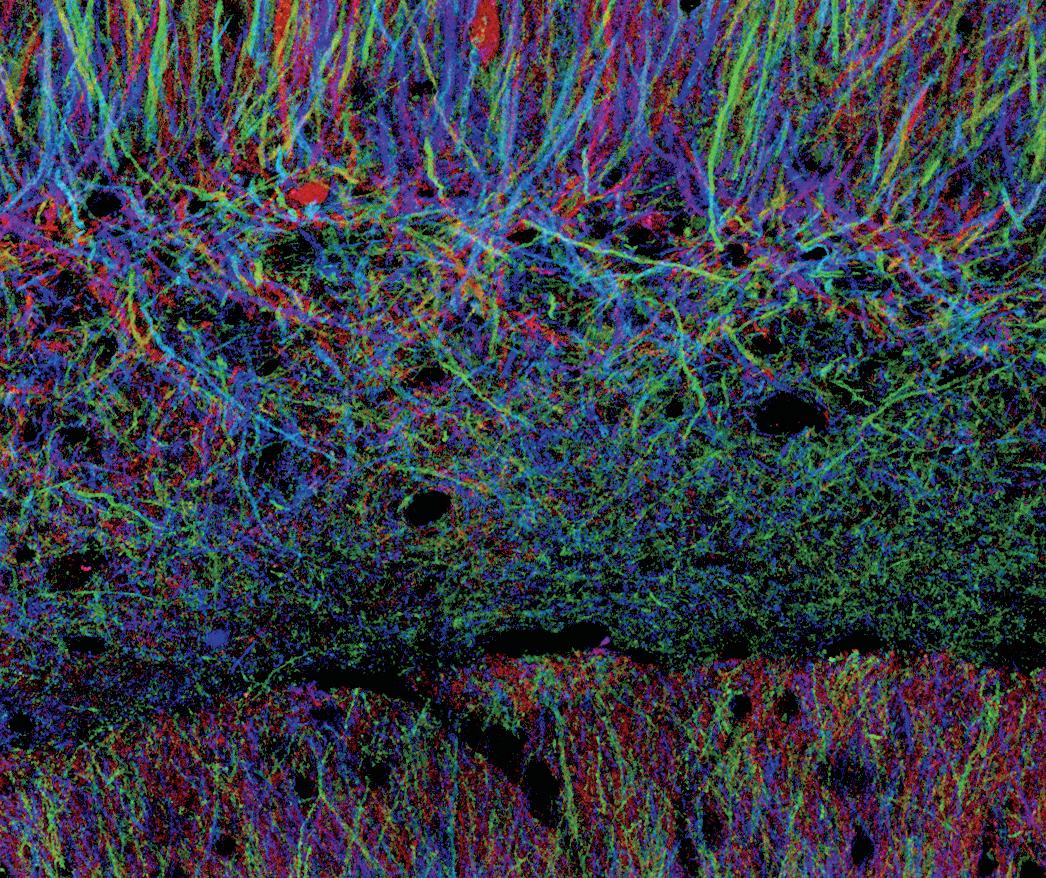

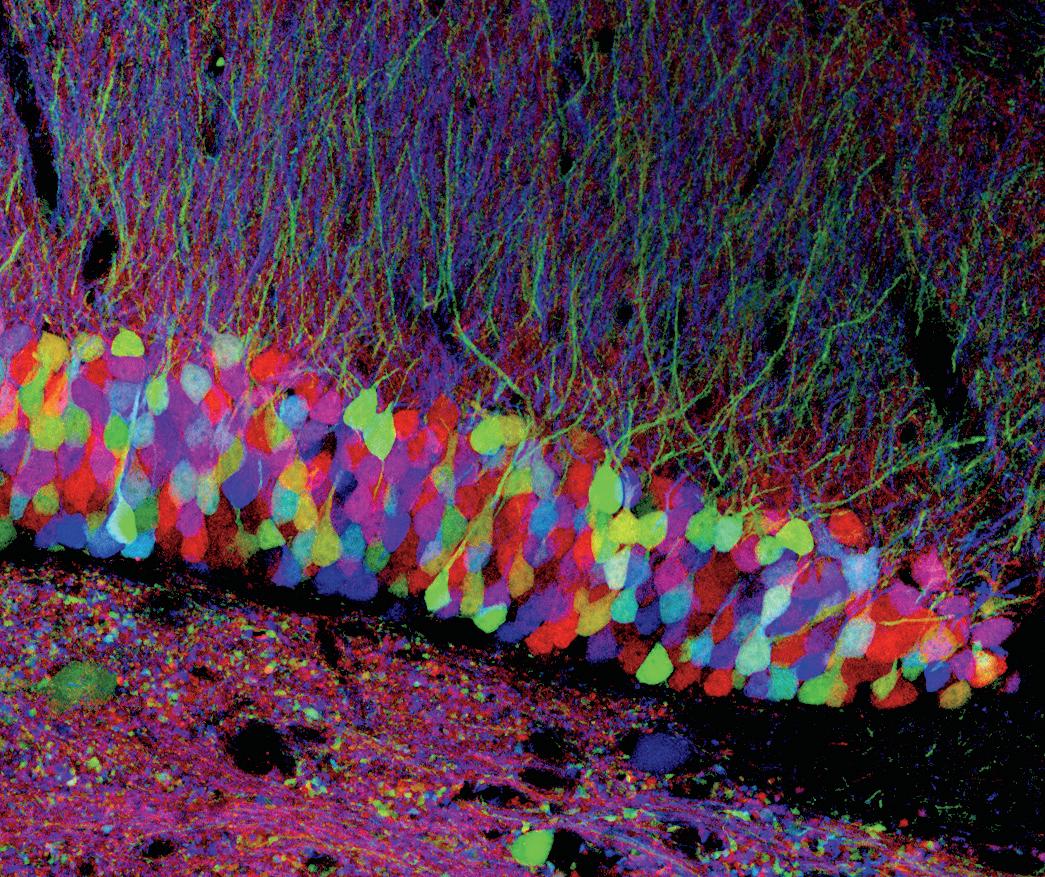

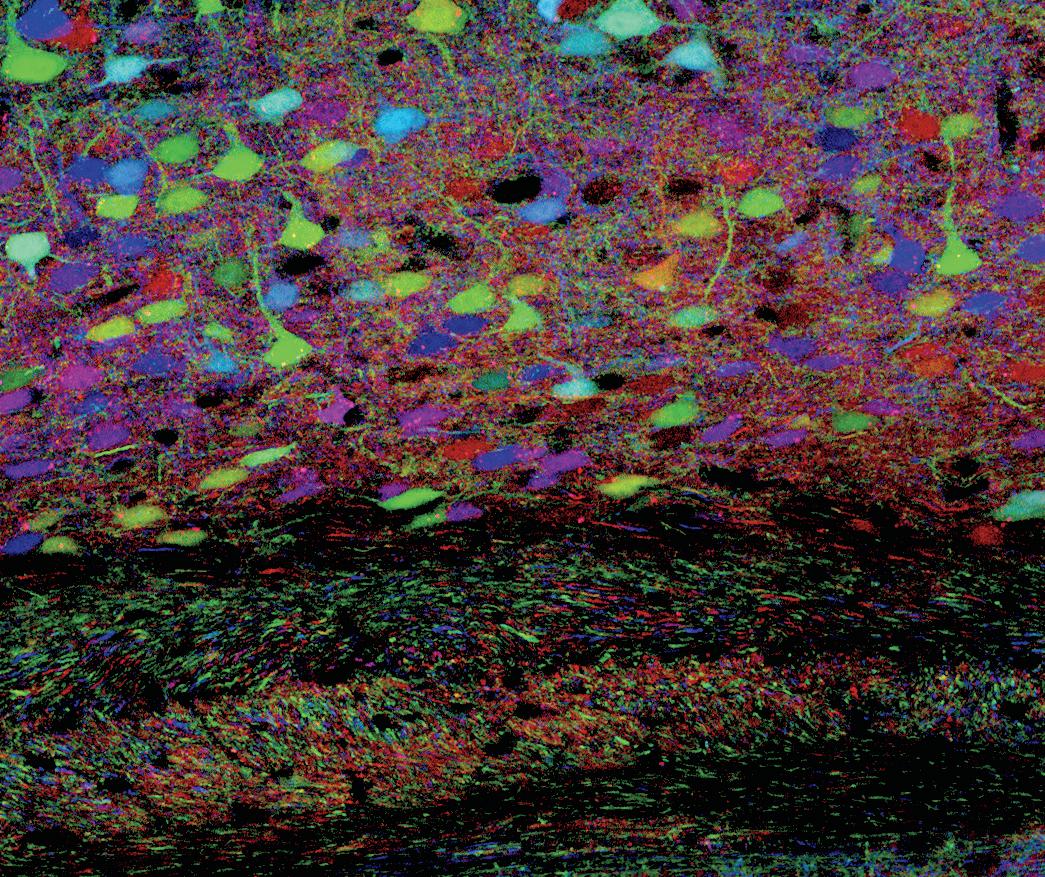

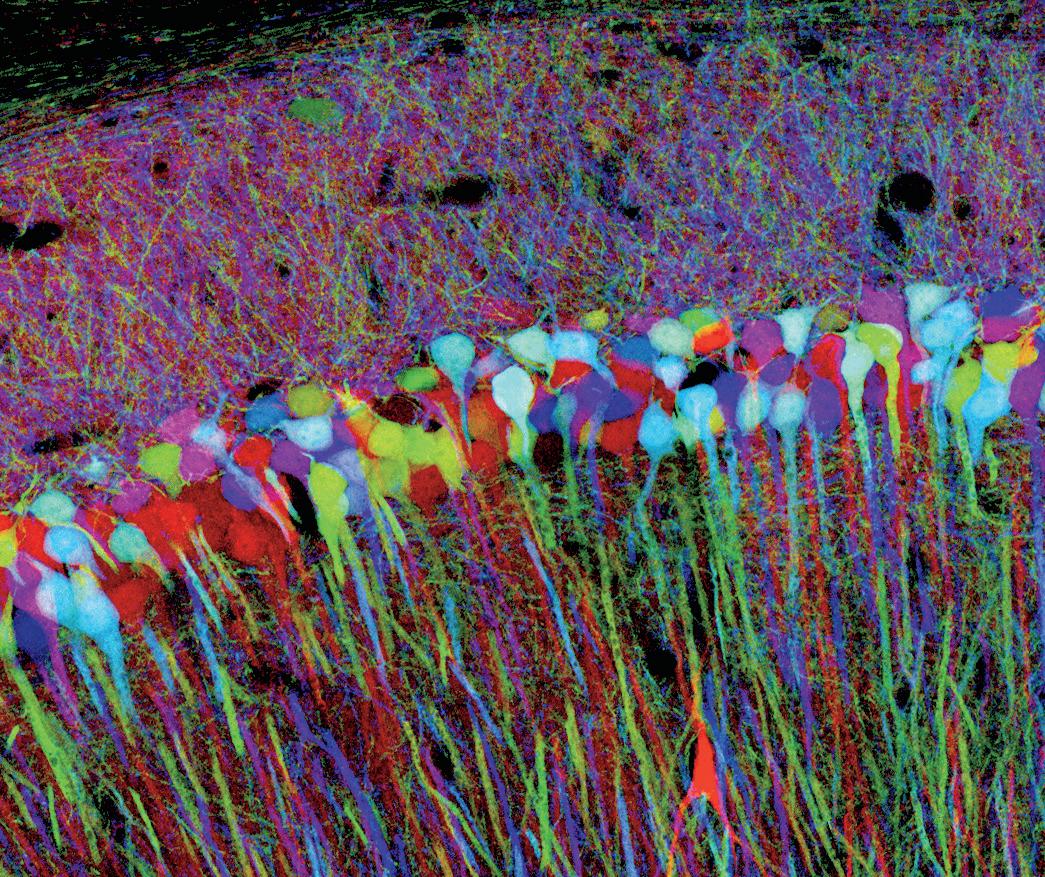

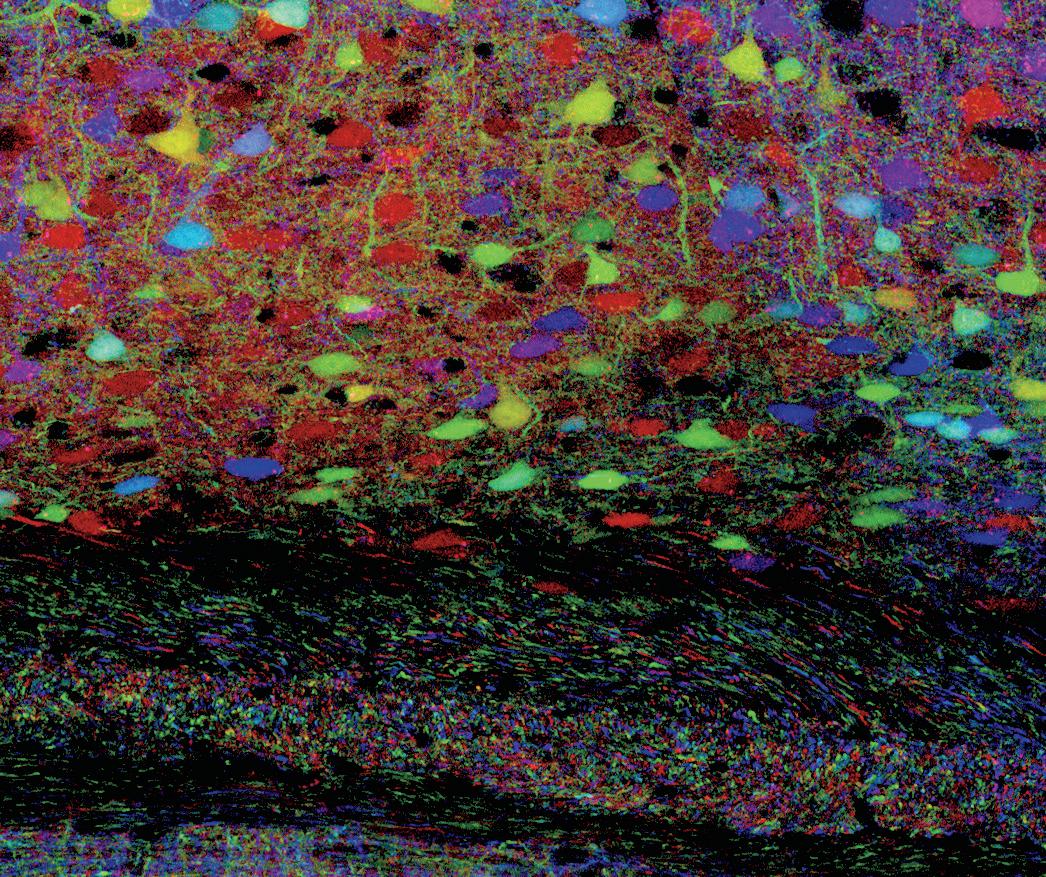

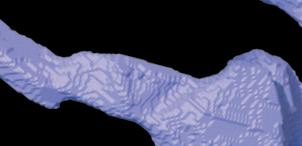

Clockwise from top left:

A pyramidal neuron from a human brain sample, with axons showing the rare whorl pattern. Of the millions of axons in the data set processed by Lichtman’s lab, only a few had these whorls.

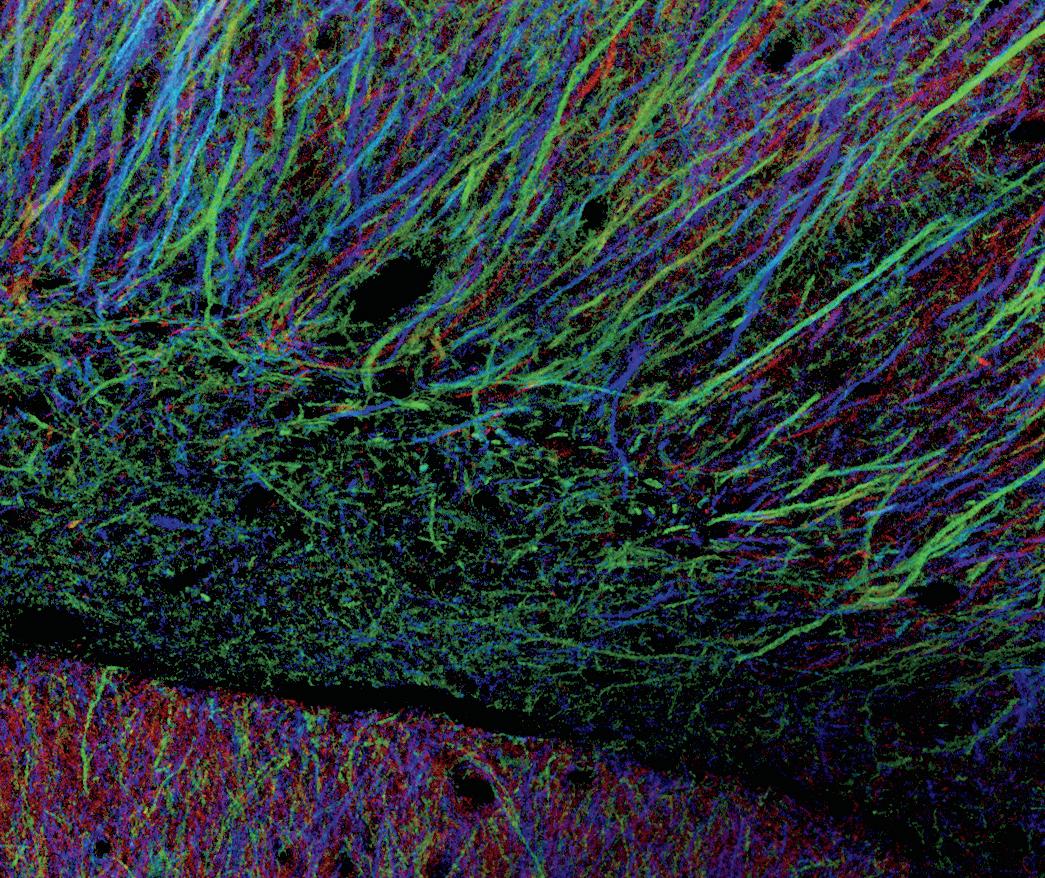

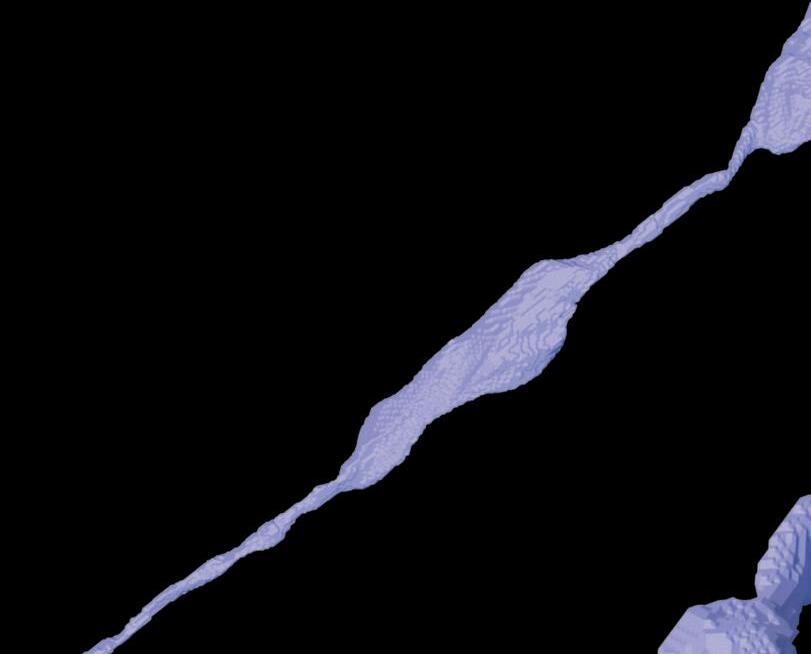

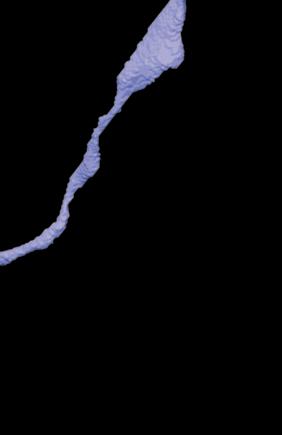

After the brain sample is sliced into 30-nanometer-thick sections and imaged, the images are reconstructed in a stack so that the components can be viewed in 3D.

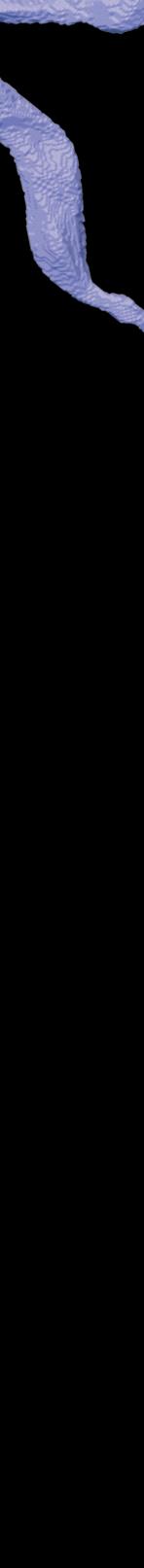

A section of mouse brain cortex showing a large dendrite (red) with axons and synapses—the points where signals pass from one neuron to another.

Neurons colored to differentiate size and to show layers. Large neurons are colored red and small ones blue.

That conviction leads him back to a principle that has influenced him since his childhood pond-water watching: the power of observation. Science is always performed through hypothesis and experimentation, he says. Whether it’s astronomers charting galaxies, particle physicists smashing atoms, or Darwin deriving evolution from finches’ beaks, sometimes the most fundamental discoveries arise from simply seeing what’s out there. If we want to cure diseases of the brain, first we must understand what the brain looks like—just like someone would need to know the way a car works to fix an oil leak or a wiring diagram to fix an electrical system. “We’re just starting to look at these wiring diagrams, and already we’re seeing things that aren’t in any textbook, just because no one has had a way to look for them before.”

Lichtman first started tracing these neuronal connections at Washington University, looking at clusters of nerves in the peripheral nervous system called the autonomic ganglia, which control subconscious functions such as sweating, goosebumps, or salivation. He laughs while recalling how he explained his dissertation work to his mother. “I told her I found this huge reorganization of the writing diagram of the salivary gland. She said, ‘What the hell—you went to school so you can study saliva in rats?’”

Beyond those specific structures, however, Lichtman was making groundbreaking progress

Lichtman realized he could more elegantly trace those connections using color. Traditionally, scientists stained a few cells at random, hoping to glimpse a connection. Stain too many, and the result was a blurry mess. Lichtman had a different idea. Using a recently discovered gene from jellyfish that produced fluorescent proteins, he realized he could manipulate it to create red, green, and blue proteins in mouse cells. By inserting those genes into cells and randomly exciting or inhibiting them, he could produce a spectrum of colors from proportions of those three colors, similar to the way a color television creates a rainbow of color through three colors of backlit pixels.

He called it the “brainbow.” Under black light, the neurons glowed in a riot of colors, each distinguishable from their neighbors under the microscope. Publishing the results in an article in Nature in 2007 that coined the word “connectomics” for the first time, Lichtman was able to showcase images of the brain that were not only informative, but also stunningly beautiful, resembling a lit-up fiber-optic Christmas tree.

While the technique worked well for the peripheral nervous system, the random colors failed to provide the resolution necessary in the densely packed central nervous system. To make sense of that tangle, Litchman and his colleagues would have to use a different approach. From his office, he leads the way down an elevator to the basement, where he shows off a machine that looks like a film projector called the automatic tape-collecting lathe ultramicrotome (ATLUM). The device, Lichtman explains, uses a diamond knife to cut sections of brain thirty nanometers thick—a thousand times thinner than a human hair.

Lichtman in his lab. To his right and behind him are multibeam electron microscopes that use ninety-one parallel beams to create the imaging speed necessary to process the enormous datasets they use. To his left is a new gas cluster milling system that allows them to generate image stacks with slices as thin as what you would get if you cut a single sheet of paper into 5,000 ultra-thin sheets.

Those sections are collected on a silicon wafer, which can be imaged separately by an electron microscope and then recollected digitally to create a three-dimensional section of tissue. After digitizing the brain slices, the scientists collaborated with Google, which worked to stitch those black-and-white images into a seamless three-dimensional representation of the brain. Using artificial intelligence, technicians have been able to trace individual neurons and color them with enough differentiation to distinguish not only individual cells, but also parts within cells.

At the pace of traditional instruments, Lichtman calculated that the tens of thousands of images for a cubic millimeter of brain would take seventeen years to complete. So, he and his colleagues built faster systems, including an

electron microscope the size of a refrigerator that can beam a shower of sixty-one streams of electrons at a time, reducing the time necessary to six months. They are now working on a new machine that will image ninety-one images at a time, connected to a device with a tangle of parts and wires that will automatically shave pieces of brain and feed them into the machine without need for human interaction.

The amount of computing power to accomplish the task has been so vast that Google has had to develop entirely new software to allow multiple computers to work on the task at once. Google research scientist Viren Jain compares it to technological innovations produced by NASA as it has worked to solve problems of spaceflight. “There are these kinds of grand problems, where if you choose something hard

For Lichtman, finding new structures like this is a thrill akin to discovering new species of animals in an unknown land.

enough, you end up inventing something that is more broadly useful.”

Back in his office, Lichtman shows off the results as he zooms on his computer monitor through a vast virtual landscape of colored wires that represents a tiny section of the cerebral cortex of a forty-five-year-old woman who was undergoing neurosurgery for epilepsy. Within that, he and his fellow researchers have discovered previously unknown brain structures. In one, which he has dubbed “whorls,” axons look like a mass of spaghetti all twisted up. It’s the kind of thing that could only be discovered in a dataset this enormous. “Very few axons in the dataset are doing this—maybe twenty out of 200 million—so it’s very rare,” says Lichtman, who speculates it might be related in some way to epilepsy, potentially serving as a marker for the disease.

In another structure he calls a “superconnection,” a nerve cell makes dozens of connections to the same cell. “For most connections, all it takes it one dendritic spine passing by a cell to create a synapse that can carry information,” Lichtman explains, zooming in to show a colored wire that connects to a cell in dozens of places, going up one side and down the other. “Instead of making one synapse, it’s making fifty-two.” He hypothesizes that these strong connections might represent firmly rooted learning, where a concept becomes automatic— the way we might instantly imagine a man with a stovepipe hat and beard from the single word “Lincoln,” or step on the brake as soon as we see a red light while driving. “You don’t have to think, ‘I have to take my foot off the gas and put

it on a brake pedal,’” he says. “It’s an automatic fast path through the brain.”

For Lichtman, finding new structures like this is a thrill akin to discovering new species of animals in an unknown land. “Suddenly there are all these birds and reptiles you’ve never seen before,” he says. “That’s how it feels, like an explorer arriving on a new continent.”

As Harvard’s new dean of science, Lichtman has been working to re-create that same spirit of exploration for students, rethinking how to approach scientific inquiry in an age of the internet and artificial intelligence. “One of the crises of science teaching is that all the information known in the world is available at the fingertips of every student with a cell phone,” he says. “I wanted to come up with a program where ChatGPT would be useless.”

The solution he came up with is a new program based on what he calls GHPs—genuinely hard problems—including the physical roots of mental illness, the nature of dark matter, and the solution to climate change. “These are problems where, despite the best efforts of modern science, we’ve made no progress,” he says. “So, students are not at as much of a disadvantage as you might think, because all the people who know everything still haven’t gotten it right.”

Students would take a class their first semester on campus in which faculty present a number of these problems, he says, and then they’d pick a faculty member who would suggest courses they could take and books and papers they could read to try to solve it over the next four years. “If they are successful, they get a Nobel Prize,” Lichtman quips. More to the point, however, they’ll get something even more essential for a budding scientist: training in a way of thinking to confront the unknown with excitement over the possibility of discovering something new.

“Most education in the sciences consists of courses in which someone tells you, ‘Trust me, you are going to need this later in life,’” he says. “But it doesn’t serve them well when we give them a bunch of things to memorize that they could get off the internet. Most of our students have gotten into Harvard by focusing on accomplishment, but that’s different than battling a

very hard problem, where you might fail many times before succeeding.”

The prime attribute he’s hoping the program engenders in students is curiosity. “Good scientists are confronting problems every day that they don’t have the answers to,” he says. “Every night they are thinking about them, and every morning, they wake up still thinking about them—they just can’t help it.”

He might just as well be talking about himself, as he works to expand on the small piece of brain he’s already helped image. With the new microscope system at Harvard, along with a similar one at Princeton, he thinks he and his collaborators can image a piece of brain ten times larger than the one in their Science paper in just two years. “If we had twenty-five of these instruments, we could do a whole mouse brain in two years,” he says. Of course, that would require massive amounts of data analysis and storage, on the order of exabytes—that is, millions of terabytes—but the payoff could be incredible. “No mammal’s wiring system is known at all,” he says. “Once we had a normal mouse, we could then do a mutant animal.”

By comparing the two, neuroscientists could potentially understand brain disease in an entirely new way, developing therapies to target the connections in the brain the same way that the Human Genome Project has led to innovative new molecular therapies. The truth, Lichtman says, is that no one knows exactly what they’ll find, what new structures await discovery in the microscopic depths of the human brain, and how they might transform our understanding of learning, memory, and illness. “People who do this work consider themselves explorers,” Lichtman says again. “We just want to see what’s out there.” On his desk, the microscope awaits—as it has for all his life—a reminder that discovery begins not with answers, but with a willingness to look closely at the world.

Michael Blanding is a Boston-based investigative journalist whose work has appeared in The New York Times, WIRED, Smithsonian, Slate, The Nation, The Boston Globe Magazine, and Boston

Jared Leeds is a lifestyle, portrait, and documentary photographer based in Boston.

Trees clean the air, fight climate change, boost our moods, and cool and protect our environment. Even a small patch of forest builds a habitat and ecosystem for other forms of life. At Bowdoin, our campus trees are part of the visual landscape, and the Pines in particular are part of the lore and the magic of Bowdoin. But they don’t persist and thrive without attention. After years of research and planning, Bowdoin is taking steps to preserve the legacy of the Bowdoin Pines. Much of it begins with life-giving light.

BY KEA KRAUSE

Tin these woods wants to play—in shafts and speckles that squeeze through the canopy, casting spotlights that move and shift across the wooded floor. A lattice of needles and leaves overhead dapples the world below. It is a forest, but it is also shimmering river rock, grainy super 8, a salmon’s spotted back, a child’s kaleidoscope.

needles to 150 years—hiding in plain sight in the heart

In other words: it is a midsummer’s day in the Bowdoin Pines, a thirty-three-acre patch of forest on the northwest corner of the College’s campus. Off a parking lot behind the offices at 85 Federal Street, this stand of tucked-away white pine can go unnoticed by harried drivers along the busy Bath Road it sits next to. But, in fact, some of those trees have been standing head to the sky for any passerby to see for close to 150 years—hiding in plain sight in the heart of Brunswick is one of Maine’s only old-growth forests. In recent years, it has come to the College’s attention that it needs a little help.

“The forest is a living, breathing thing,” remarks Tom Doak, executive director of Maine Woodland Owners. “It’s changing all the time.” Which is why, after decades of the College allowing nature to run its course, trees began to fall—both within the Pines and from the Pines out onto Bath Road. After a series of particularly powerful storms in 2018 and 2019, it became clear that the forest had indeed changed. Trees had gotten sick; some had died of old age and some because of the aggressions of the white pine weevil, a pesky beetle that targets a tree’s leader branch, killing it off in service of its larvae and with it the tree’s future growth. Plants of concern like knotweed and periwinkle had moved into the understory, and hardwood trees like oak and maple began to win in competition with the ancestral pines. A committee was formed to address the forest’s woes, and from the committee came a plan, which in part enlisted the expertise of Doak—a forester by training who was more than happy to help, having grown up in Maine being dazzled by trees. “I remember driving as a kid by the Bowdoin Pines and being so impressed by them,” recalls Doak. “One of the reasons I got into forestry, frankly, was the impact of the Pines.”

In theory, the plan was straightforward: return the portion of the Pines off Bath Road to white pine dominance by removing the problematic

trees flagged by Doak and Harold Burnett, a forester with Two Trees Forestry, opening up the canopy and allowing for the growth of a large cohort of pine seedlings, the result of a 2023 abundance of seeds, known as a mast year. In practice, there were many more factors than the trees to consider. “We were worried that our actions would be misinterpreted or misunderstood or outright opposed,” says Burnett, as he explains that community outreach prior to the remediation of the Pines rivaled the remediation itself in terms of importance. Beyond what the Pines meant to the campus—to current and former students and even to some of the College’s curriculum—the Brunswick community uses the one-kilometer trail that winds through those woods for dog-walking, bird-watching, and nature breaks more generally, and the sight of the heavy equipment used to clear out trees can be alarming, especially when it comes to some of these centenarian trees, Doak says.

As I walk among them, the light plays tricks along the furrowed bark of a massive trunk, luring my gaze upward. The first thing to know about the white pine: its trunk is flawlessly straight, like a vertical runway to the sky. So linear are the trunks that in the 1600s, word from the colonies made its way back to the King of England that there was a species of tree in the New World that produced perfect ship masts, and soon the king’s minions were marking pines for the taking. Maine pine would become the solution for modernity’s many needs: the wood is soft, abundant, and ideal both for framing a house and for flooring one. Thoreau condemned the use of trees for anything other than marveling, writing in his book The Maine Woods, “strange that so few ever come to the woods to see how the pine lives and grows and spires, lifting its evergreen arms to the light—to see its perfect success, but most are content to behold it in the shape of many broad boards brought to market, and deem that its true success!” You reckon with stories like these when you let yourself peer eighty feet from base to canopy of one of these giants, the juxtaposition of its hale trunk and its dainty, feather-like needles a contradiction worthy of Thoreau’s notion of perfect success.

It’s no wonder Doak, Burnett, and the rest of the committee were worried about what some

THE FOREST IS A LIVING, BREATHING THING. IT’S CHANGING ALL THE TIME.

might feel when they saw machinery moving into the Pines. But just as there is a misconception that big equipment always means destruction, there is another that caring for a forest invariably means leaving it alone. As Doak explains, the mission of forestry falls somewhere in the middle of this spectrum of purposeful intervention and complete neglect. “You’re not playing with nature,” he says. “You’re just kind of figuring out ways to assist it.” Encouraging the Pines in one direction—white pine dominance—and away from what would happen if the woods there were left untouched also raised another important question about how to care for a forest: What would Bowdoin’s stewardship ethos be? More simply, what is stewardship in this case?

TONY SPRAGUE arrives at the trailhead in crisp office attire and a pair of hiking boots. Sprague, Bowdoin’s campus planner, is going to show me the results of the remediation of a section of the Pines that took place over three weeks this past June. As part of the plan, a pocket of woods has been left entirely untouched and will serve as both a test control to compare with the managed sections and an outdoor laboratory for the College’s science programs. It is the reserve that you first walk through when you head out of the parking lot behind the offices.

Sprague leads the way through this first dense passage of the loop. “This section has transitioned further away from white pine dominance,” he says, explaining the logic of the placement of the reserve plot. “The amount of intervention that would’ve been necessary to try to restore [this space] would have been more than anybody would’ve been comfortable with.” I follow along behind Sprague, noting little orange flags stuck in the ground off the trail, indicating where student work is underway, like a study on the effect of road salts on ground cover. A gray flash of a squirrel interrupts the balayage of green. The reserve feels like typical roadside woods: oaks and evergreens intermix, while ferns unfurl at their bases. There is bittersweet— another plant of concern—and partridge berry, and if you close your eyes and listen for them, a lot of birds. Mostly pine warblers today. The light is aggressive, and so is the humidity.