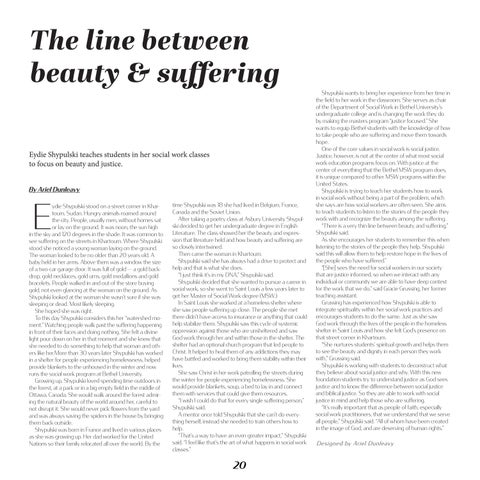

The line between beauty & suffering Eydie Shypulski teaches students in her social work classes to focus on beauty and justice. By Ariel Dunleavy

E

ydie Shypulski stood on a street corner in Khartoum, Sudan. Hungry animals roamed around the city. People, usually men, without homes sat or lay on the ground. It was noon, the sun high in the sky and 120 degrees in the shade. It was common to see suffering on the streets in Khartoum. Where Shypulski stood she noticed a young woman laying on the ground. The woman looked to be no older than 20 years old. A baby held in her arms. Above them was a window the size of a two-car garage door. It was full of gold — a gold backdrop, gold necklaces, gold urns, gold medallions and gold bracelets. People walked in and out of the store buying gold, not even glancing at the woman on the ground. As Shypulski looked at the woman she wasn’t sure if she was sleeping or dead. Most likely sleeping. She hoped she was right. To this day Shypulski considers this her “watershed moment.” Watching people walk past the suffering happening in front of their faces and doing nothing. She felt a divine light pour down on her in that moment and she knew that she needed to do something to help that woman and others like her.More than 30 years later Shypulski has worked in a shelter for people experiencing homelessness, helped provide blankets to the unhoused in the winter and now runs the social work program at Bethel University. Growing up, Shypulski loved spending time outdoors in the forest, at a park or in a big empty field in the middle of Ottawa, Canada. She would walk around the forest admiring the natural beauty of the world around her, careful to not disrupt it. She would never pick flowers from the yard and was always saving the spiders in the house by bringing them back outside. Shypulski was born in France and lived in various places as she was growing up. Her dad worked for the United Nations so their family relocated all over the world. By the

time Shypulski was 18 she had lived in Belgium, France, Canada and the Soviet Union. After taking a poetry class at Asbury University Shypulski decided to get her undergraduate degree in English Literature. The class showed her the beauty and expression that literature held and how beauty and suffering are so closely intertwined. Then came the woman in Khartoum. Shypulski said she has always had a drive to protect and help and that is what she does. “I just think it’s in my DNA,” Shypulski said. Shypulski decided that she wanted to pursue a career in social work, so she went to Saint Louis a few years later to get her Master of Social Work degree (MSW.) In Saint Louis she worked at a homeless shelter where she saw people suffering up close. The people she met there didn’t have access to insurance or anything that could help stabilize them. Shypulski saw this cycle of systemic oppression against those who are unsheltered and saw God work through her and within those in the shelter. The shelter had an optional church program that led people to Christ. It helped to heal them of any addictions they may have battled and worked to bring them stability within their lives. She saw Christ in her work patrolling the streets during the winter for people experiencing homelessness. She would provide blankets, soup, a bed to lay in and connect them with services that could give them resources. “I wish I could do that for every single suffering person,” Shypulski said. A mentor once told Shypulski that she can’t do everything herself, instead she needed to train others how to help. “That’s a way to have an even greater impact,” Shypulski said. “I feel like that’s the art of what happens in social work classes.”

20

Shypulski wants to bring her experience from her time in the field to her work in the classroom. She serves as chair of the Department of Social Work in Bethel University’s undergraduate college and is changing the work they do by making the masters program “justice focused.” She wants to equip Bethel students with the knowledge of how to take people who are suffering and move them towards hope. One of the core values in social work is social justice. Justice, however, is not at the center of what most social work education programs focus on. With justice at the center of everything that the Bethel MSW program does, it is unique compared to other MSW programs within the United States. Shypulski is trying to teach her students how to work in social work without being a part of the problem, which she says are how social workers are often seen. She aims to teach students to listen to the stories of the people they work with and recognize the beauty among the suffering. “There is a very thin line between beauty and suffering,” Shypulski said. As she encourages her students to remember this when listening to the stories of the people they help. Shypulski said this will allow them to help restore hope in the lives of the people who have suffered.” “[She] sees the need for social workers in our society that are justice informed, so when we interact with any individual or community we are able to have deep context for the work that we do,” said Gracie Grussing, her former teaching assistant. Grussing has experienced how Shypulski is able to integrate spirituality within her social work practices and encourages students to do the same. Just as she saw God work through the lives of the people in the homeless shelter in Saint Louis and how she felt God’s presence on that street corner in Khartoum. “She nurtures students’ spiritual growth and helps them to see the beauty and dignity in each person they work with,” Grussing said. Shypulski is working with students to deconstruct what they believe about social justice and why. With this new foundation students try to understand justice as God sees justice and to know the difference between social justice and biblical justice. So they are able to work with social justice in mind and help those who are suffering. “It’s really important that as people of faith, especially social work practitioners, that we understand that we serve all people,” Shypulski said. “All of whom have been created in the image of God, and are deserving of human rights.” Des i gne d by Arie l Dunleavy