Old, new and equitable ways of producing coffee FAMILY FARM OWNERS, COOPERATIVES AND LOCAL ARTISANS MODERNIZE COFFEE CONSUMP TION WHILE STAYING TRUE TO THEIR ROOTS. By Ella Roberts

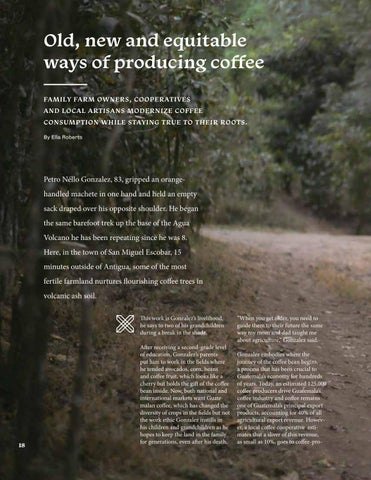

Petro Néllo Gonzalez, 83, gripped an orangehandled machete in one hand and held an empty sack draped over his opposite shoulder. He began the same barefoot trek up the base of the Agua Volcano he has been repeating since he was 8. Here, in the town of San Miguel Escobar, 15 minutes outside of Antigua, some of the most fertile farmland nurtures flourishing coffee trees in volcanic ash soil. This work is Gonzalez’s livelihood, he says to two of his grandchildren during a break in the shade.

18

After receiving a second-grade level of education, Gonzalez’s parents put him to work in the fields where he tended avocados, corn, beans and coffee fruit, which looks like a cherry but holds the gift of the coffee bean inside. Now, both national and international markets want Guatemalan coffee, which has changed the diversity of crops in the fields but not the work ethic Gonzalez instills in his children and grandchildren as he hopes to keep the land in the family for generations, even after his death.

“When you get older, you need to guide them to their future the same way my mom and dad taught me about agriculture,” Gonzalez said. Gonzalez embodies where the journey of the coffee bean begins, a process that has been crucial to Guatemala’s economy for hundreds of years. Today, an estimated 125,000 coffee producers drive Guatemala’s coffee industry and coffee remains one of Guatemala’s principal export products, accounting for 40% of all agricultural export revenue. However, a local coffee cooperative estimates that a sliver of this revenue, as small as 10%, goes to coffee-pro-