5 minute read

No easy atonement: When making amends costs us

By Rabbi Kendell Pinkney

Fall is a complicated time of year. At least it is for me. On the one hand, the body and mind feel the loss of summer’s ease: no more summer Fridays at the office, gone are the ample, long weekends to Instagrammable coastlines, farewell to summer empty nests purged of school-aged children. On the other hand, fall brings a palpable sense of purposefulness: the start of the school year, fuller work weeks matched with fuller expectations, the start of a new theatre season…ahem-ahem.

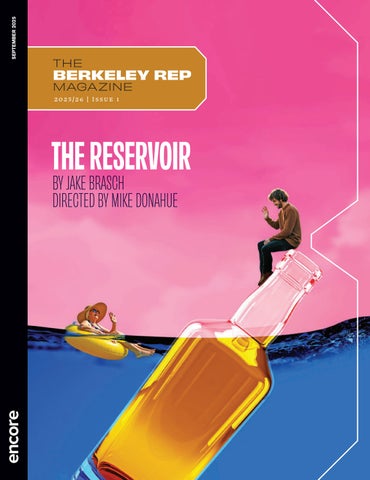

The 2025/26 season at Berkeley Rep opens with The Reservoir — a hilarious, madcap fever-dream-of-a-play about Josh, a charismatic, queer, Jewish twenty-something caught in the tottering throes of a journey towards sobriety. As a theatre artist and ordained rabbi, I devoured the play twice in one sitting. It is easy to love Josh, and equally easy to find him vexing. What is most surprising, however, is how poignantly this story of addiction and recovery maps onto the themes and concerns of Jewish ritual time.

The Reservoir’s run happens to fall during Judaism’s holiest day of the year: Yom Kippur, i.e., “the day of atonement” (October 1–2). A day characterized by somberness, self-reflection, lengthy prayers, contrition, and fasting, Yom Kippur is the ritual culmination of a month-long period where Jewish folks, at least traditionally, hope to attain atonement, or make amends for wrongs they have committed in the previous year. It also happens to be the one day of the year that large numbers of Jewish Americans, including many secular atheist Jews, actually go to synagogue.

While the above description gives an accurate, if bare-bones, snapshot of the holiday, I have long found Yom Kippur especially interesting because beneath its ritual and cultural specificity it addresses a set of profoundly universal questions: What does it mean for a human to make amends? What does atonement look like? How does one go about making things right? — all questions The Reservoir is intimately concerned with.

In Judaism — at least according to the medieval Egyptian-Spanish commentator, Maimonides — making amends is an arduous process. For example, let’s say you’re out with friends for a night on the town. You settle into a booth at your favorite haunts. Spirits are high, cups are full, the music is blaring, and just as festivities are revving up you accidentally insult and deeply offend one of your friends. According to Maimonides you will need to go to this friend, look them in the eyes, name your precise misdeeds, and ask their forgiveness. If they don’t accept your apology, you’re not off the hook. You are then required to grab three friends (presumably the other friends who witnessed the offense) to accompany you to return and ask forgiveness, again. If your friend still won’t accept your apology, well, I’ll give you two guesses as to what comes next and you won’t need the second guess. In short, atonement is harder than it looks.

The process of making amends in Alcoholics Anonymous is no less rigorous: the alcoholic is required to make a personally “searching and fearless moral inventory,” they must make a list of people they have harmed, they are then urged to develop the courage to make amends with people they have harmed, and finally, they must develop the discernment to ensure that they do not cause more harm in the process of making amends.

If you are anything like me, reading the above Jewish and AA accountability guides provoked an allergic reaction. That is completely understandable. It is much more comfortable to wade in the shallows of our intentions and private mistakes than it is for us to tread into the deep waters of publicly owning how we have harmed others, wronged those we love, and let ourselves down. To face such a reality feels perilous, potentially exposing us to waves of guilt and shame that threaten to completely overwhelm us. Both Judaism and AA’s approaches to accountability are so sobering because they are achingly relational, vulnerable, communal, and counter-cultural.

Perhaps this is why the traditions of Jewish atonement and AA’s 12 Steps refuse to offer easy absolution. They believe atonement should be thorough. It should cost us something. They insist that we sit with discomfort, that we return again and again to the work of repair, that we allow our communities to witness our vulnerability. In a culture increasingly comfortable with easy apologies and excuses, these ancient and modern practices remind us that genuine reconciliation requires something more radical: the willingness to be changed by the process itself. Whether it’s the Jewish devotee approaching Yom Kippur in trembling and awe or the alcoholic counting days of sobriety, both understand that atonement isn’t a destination but a way of being — one that transforms not just our relationships with others, but our very understanding of what it means to live with integrity. And maybe, in this delicate moment as the season changes and our perspectives shift along with it, The Reservoir can remind us that that’s exactly the kind of transformation we need.

Kendell Pinkney is a Brooklyn-based theatre artist and rabbi. His plays and musicals have been commissioned, developed, and presented at venues across the US and Canada. In addition to his creative work, Kendell is the Rabbinical Educator and Artist-in-Residence at the Jewish arts and culture organization Reboot. Additionally, he serves as the founding Artistic Director of The Workshop, one of Reboot’s signature fellowships for emerging creatives of BIPOC-Jewish heritage. NYU-Tisch Graduate Musical Theatre Writing, MFA. kendellpinkney.com