4 minute read

Fictionalizing the personal

A conversation with Jake Brasch

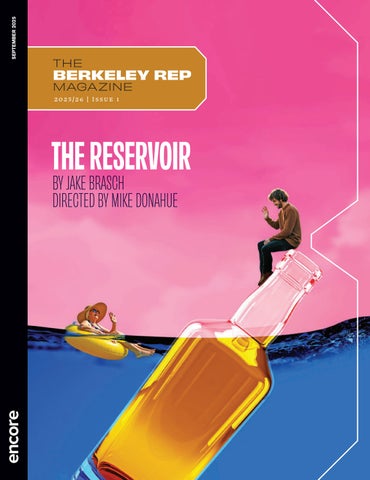

Writing a play is always an act of emotional vulnerability. But in a semi-autobiographical piece like The Reservoir, the personal, spiritual, and brutally honest material asks even more from playwright Jake Brasch. We sat down with Jake to discuss the mechanics of turning life into art, how Jewish tradition can help us contend with uncertainty, and the importance of laughter in theatre — and in life.

ON FICTIONALIZING THE PERSONAL

Whenever people ask if the play is autobiographical, I say, “Uh-oh! You got me! I’m Shrimpy!” The play is semi-autobiographical. There’s a lot of me in Josh, but there’s also a whole lot of fiction. There’s a George Saunders quote I love: he says a story isn’t real life, it’s “like a table with just a few things on it, carefully chosen.” I wanted to focus foremost on telling a compelling story. I also wanted to put some distance between Josh’s family and mine. I take comfort in knowing that the audience can’t tell what’s true.

Also, I found that a degree of artifice was actually helpful in sharing the gunkiest parts of myself. Paradoxically, I found that fictionalizing gave me the permission to tell the truth.

ON THE USE OF HUMOR

In my family, humor is serious. It’s our currency, our coping mechanism, it’s how we connect. But it’s also how we evade, how we hide, how we get in our own way. I was curious to capture that dynamic in the play.

The Reservoir is neither a comedy nor a drama. You could argue it’s a farce, but you could make an equally compelling argument that it’s a tragedy. I’ve come to trust the enigma. The play wants to unbalance you. It wants to pull the rug out from under you at every turn. That’s what it felt like to be inside a family in crisis. I firmly believe that you have to cry to laugh, and you have to laugh to cry.

Also my grandparents were some of the funniest people I’ve ever met. To honor them, I knew I’d need to land the jokes.

ON JUDAISM

This play is about an interfaith family, and yet it feels so deeply Jewish to me. I think that’s largely because of the way it engages with humor. Jews have survived through our humor.

But I also think it has to do with recovery — and with the way Josh approaches spirituality. He finds power in not knowing. He begins to understand that the questions are more essential than the answers. Many newly sober people are put off by the spiritual component of 12-step groups. I found joyful recovery when I realized that spirituality can mean ritual, food, stories, and conversation. It can be about curiosity more than belief. And that feels deeply Jewish to me.

ON RECOVERY AND DEMENTIA

To anyone afraid that recovery is glum — fear not! Hanging out with sober drunks is a hoot. Meetings are way more entertaining than bars. It’s hard to imagine my life without the irreverence and gallows humor of recovery.

As for dementia, I take comfort in knowing that one of the only things we can do to protect ourselves is to live a joyful life. The science backs this up. Yes, Alzheimer’s is a harrowing disease, and it’s also deeply human. It has touched nearly every family. We should talk about it more.

I hope the play offers a way to cry and laugh our way to engagement with the hard stuff, to relish mystery in growing older, and to believe in second chances for those who have lost their way.

It doesn’t escape me that a play about the hardest year of my life is opening so many doors for me. It just goes to show you: You never know what’s at the end of the tunnel. Keep going. Stay present. Take the next step. There’s light on the other side.