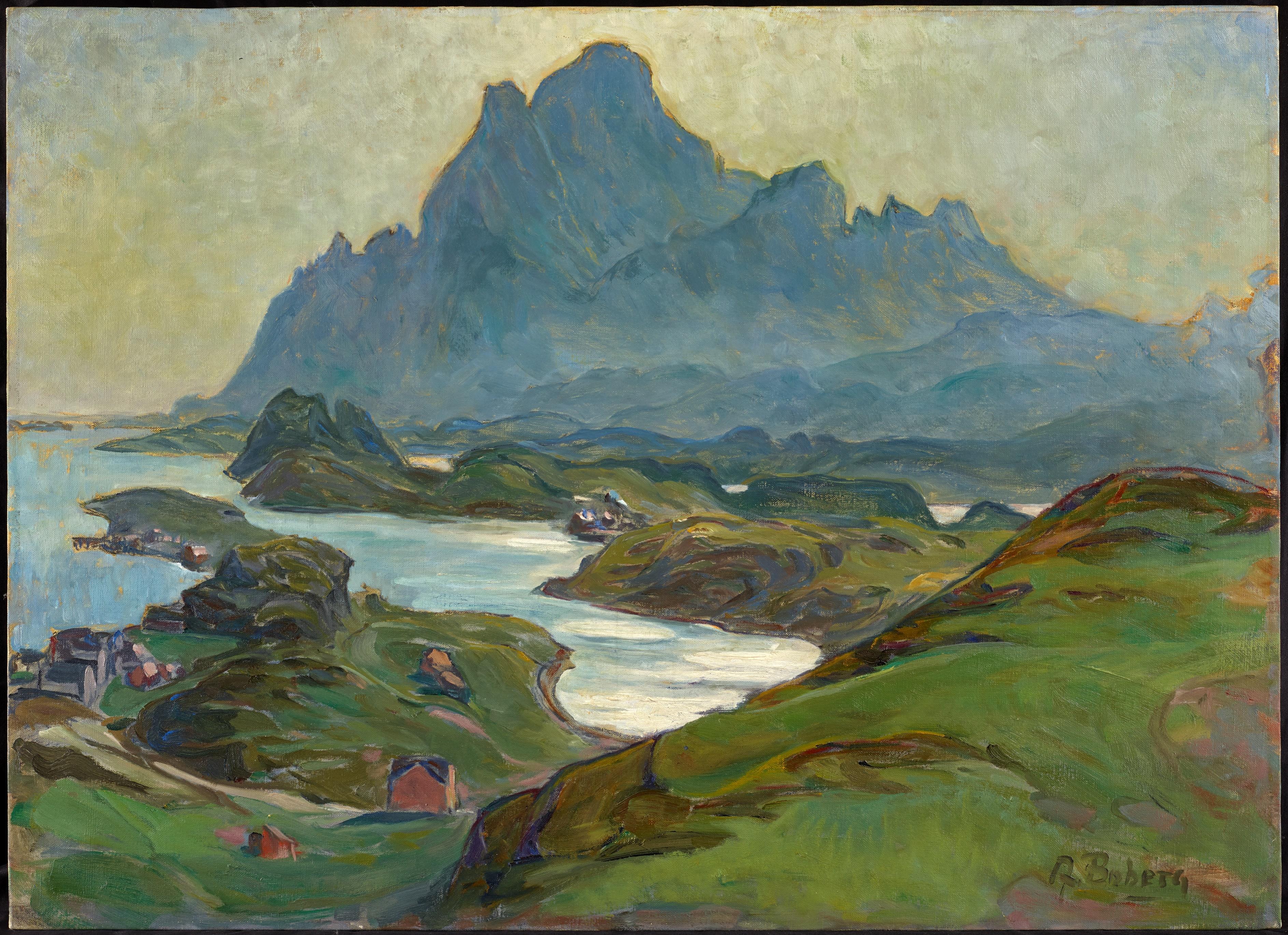

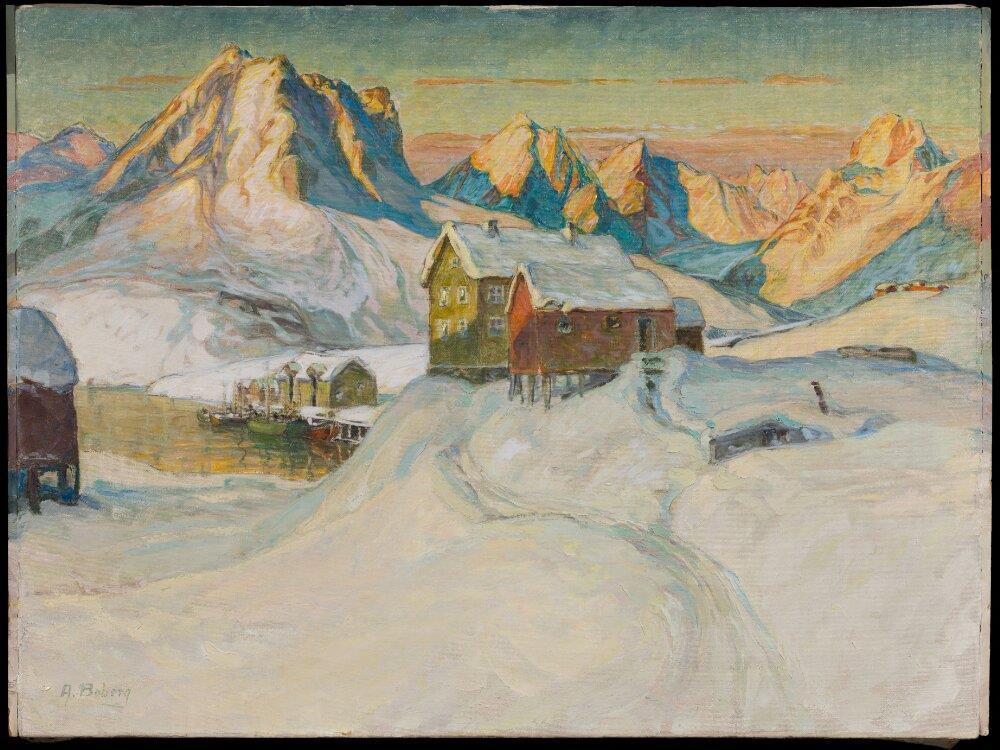

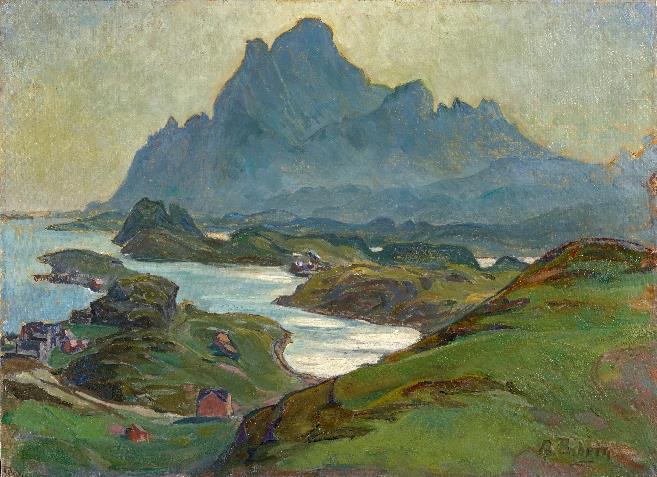

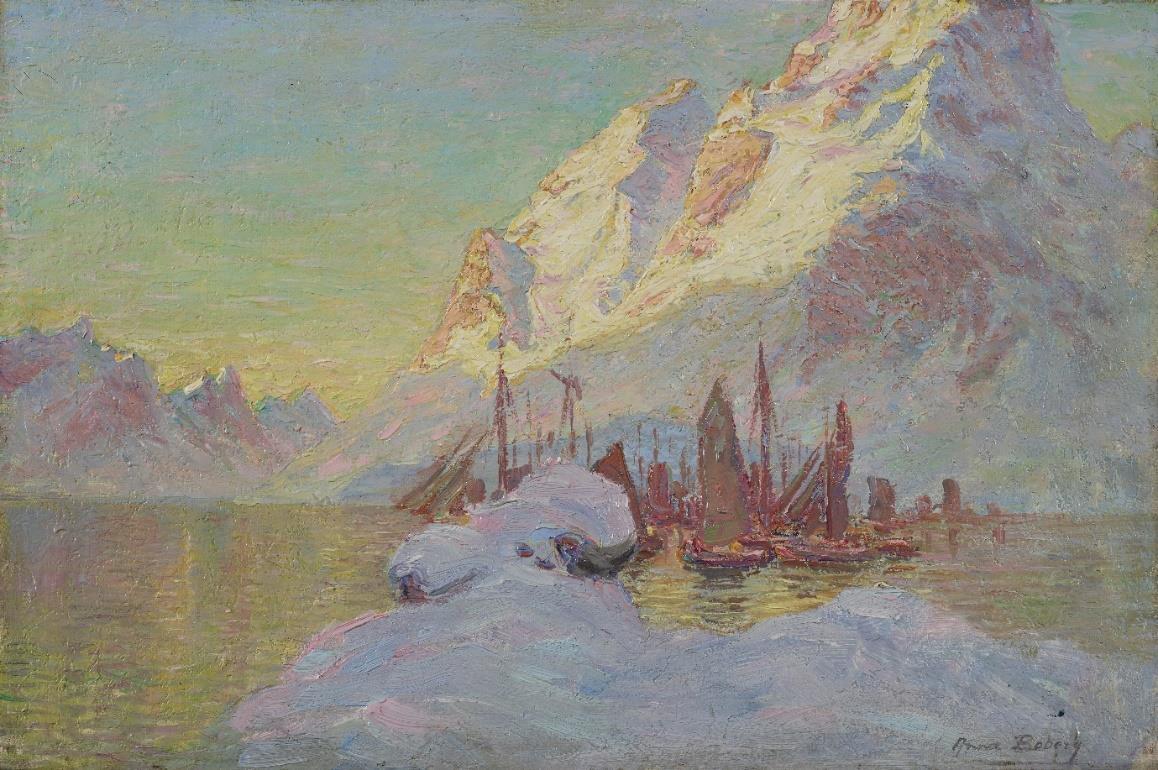

Anna Boberg (1864-1935)

Summer,c.1911-1934

59 x 81 cm

Signed lower right: A.Boberg

Full image reproduced above

Anna Boberg (1864-1935)

Painting the Arctic Summer

Dr Isabelle Gapp University of Aberdeen

no other place are the calms so absolute, the storms so terrific. The sun shines at midnight, and it is night at noon. From one moment to another the landscape changes: storms burst suddenly without any warning; fogs almost palpable in their density hide the world away in an instant.

Anna Boberg, 1808

Asreferencedin,Eva-CharlottaMebius,AnnaBoberg(1864-1935),‘Summer’, c.1911-1934(London:BenElwesFineArt,2024)

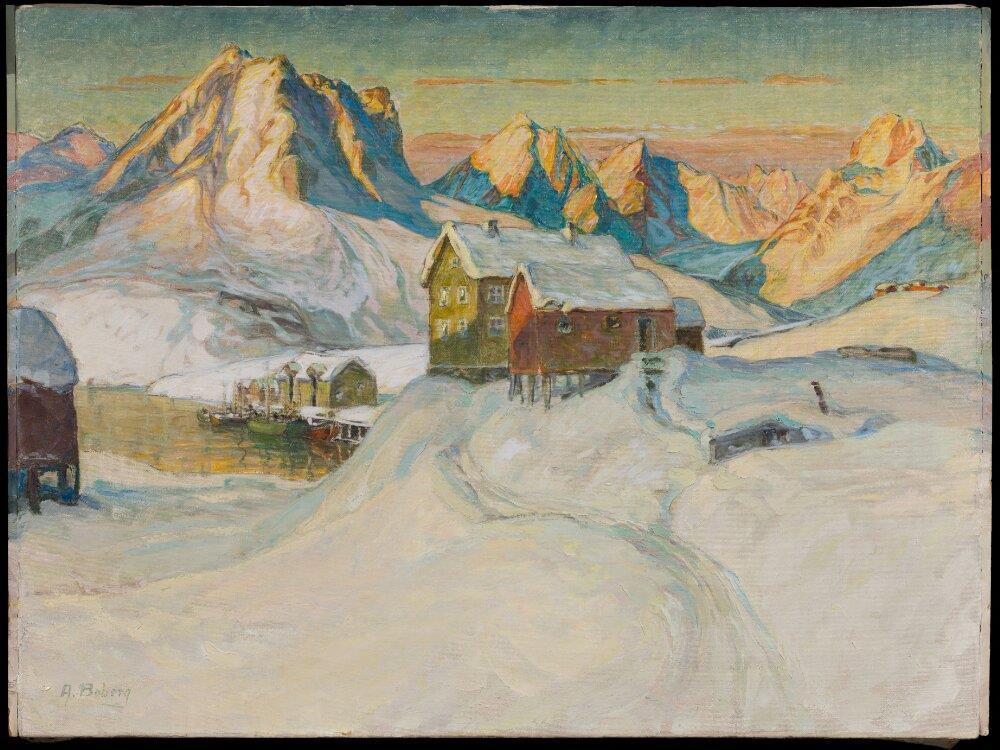

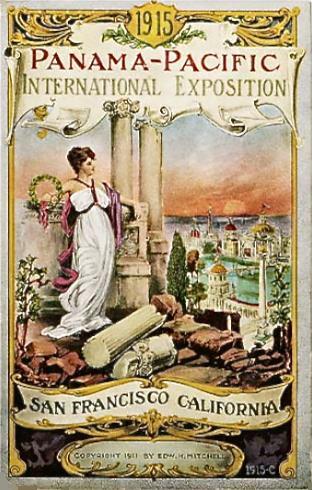

In 1915, following the Panama-PacificInternationalExpositionin San Francisco, the American art critic Christian Brinton wrote that viewers could ‘instantly discern in the work of the Swedes in the bold Lofoten island sketches of Anna Boberg […]—a frankness of vision and directness of presentation as rare as they are stimulating.’1 In a review of the same art exhibition, Eugene Neuhaus described the distinctiveness of Boberg’s landscapes, an artist who ‘when one considers the proverbial clones of the Arctic seas, her interpretations seem marvellous in their beauty and richness of colour.’2 Colour and tonalism prevailed in early twentieth-century painterly fascinations with the Arctic; with many artists, including Boberg, the Canadian Group of Seven, Rockwell Kent, among others, all exploring the variations of colour that emerge as light refracts and reflects off the snow, ice, mountains, and water.3 This contrasted with an earlier preoccupation with describing the Arctic as a white, desolate, and uninhabited environment, a ‘temperate-normative’ space to borrow from Eyak geographer Jen Rose Smith.4 Boberg further described herself as giving ‘an illusory glimpse of a polar researcher’, contributing, through her artwork, a scientific understanding of the Arctic environment.5 Her glacial paintings, especially Engabreen, SvartisenGlacier(fig. 1) painted during the summer, is believed to be

Anna Boberg (1864-1935)

Engabreen,SvartisenGlacier,Norway Oil on canvas, 47 x 46 cm

Private Collection.

shown in this exhibition for the first time.6 Boberg’s use of colour further reveals a preoccupation with conveying the changing seasons, times of day, weather, and meteorology of the Norwegian Arctic.

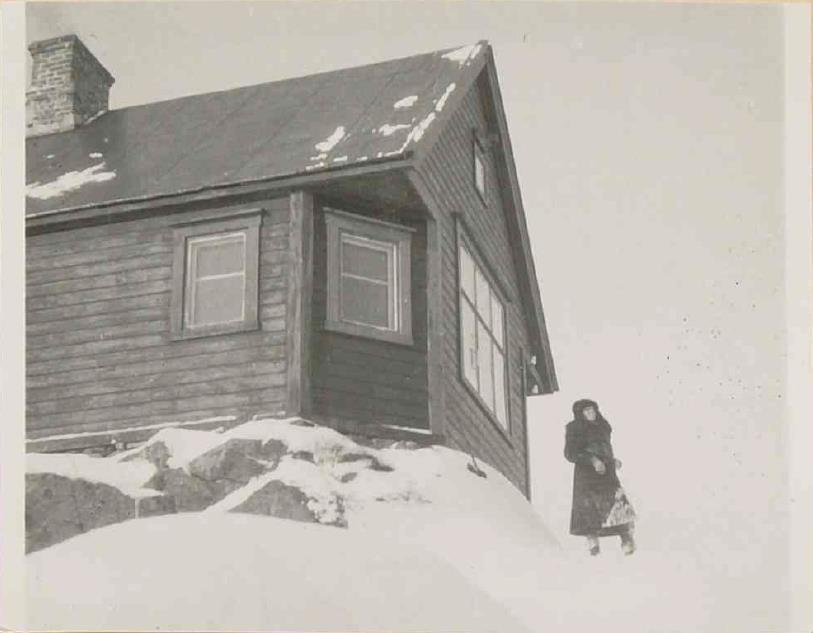

For over thirty years, from 1901 until 1934, Anna Boberg and her husband, the architect Ferdinand Boberg (1860-1946), frequently visited the Arctic, specifically the Lofoten Islands off the north-west coast of Norway. In the Lofoten archipelago, Boberg and her husband constructed their own home and studio overlooking Vestfjord and the Svolvær harbour (fig. 2), a prominent village in the Norwegian cod and herring fishing industry. The journalist Hanna Astrup Larsen, writing in TheCraftsman , described ‘a tiny hut on a wind-swept knoll of the Lofoten Islands is where Anna Boberg lives and paints. She draws her inspiration from the Arctic sea that stretches to the westward with breakers frothing almost at her feet and from the mountains that stand guard

stand guard around her home.’7 A painting from within the Nationalmuseum Collections in Stockholm denotes a view FromMy Island (fig. 3). The pastel shades of sunset filter through the lowhanging clouds and cast their reflections on the mountains, while ski tracks carve a path through the snow, following the Svolvær coastline. Scenes of the harbour and of the fjord reverberate throughout Boberg’s oeuvre and appear in many of the works exhibited here.

Many of Boberg’s Arctic experiences were also documented in her Swedish-language autobiography Envarsittödeslekbollof 1934. Here, she remarked how she ‘was so taken with the Lofoten nature that I simply refused to travel home. I wanted to stay and paint, paint, paint.’8 Gouache and watercolour sketches, oil paintings, and photographs all characterised these Arctic visits, often paintedenpleinairor from her Svolvær studio overlooking the mountainous coastline of the harbour. With an emphasis on the Arctic summer landscape, this exhibition and catalogue essay traces Boberg’s approach to landscape painting, from her early watercolour studies from Stockholm to her wonderfully varied scenes of Lofoten and Arctic Norway, from close-cropped compositions to expansive vistasof the harbour overlooking Vestfjord. They provide a far northern alternative to impressionism and contrast with the earlier notion of the Arctic as a white space, by instead exhibiting an environment that is full of colour, light, and texture.

Figure 2

Ferdinand Boberg (1860-1946) Annaoutsidethe WinterCottage

KoB Ferdinand Boberg Collection, SE S-HS L57:35.

Summertime Studies from Stockholm

Despite the defined thirty-year period that the Bobergs spent travelling to the Norwegian Arctic, it is more unusual for Anna Boberg’s work to have dates than not. While there has been a recent impetus to ascribe dates to several of her paintings, the author has as yet been unable to validate how these dates were attributed. This attempt to attribute dates to Boberg’s work appears to be growing as public and scholarly interest in her work becomes increasingly international. And yet, Boberg appears to have associated timelessness with the Arctic, removing any specificity between her work and the period during which she residedwithin this environment. Moreover, her painterly style does not appear to follow a linear trajectory, rather during the early twentieth century, there appears a wide varietyof stylisticapproaches andcolour palettes, many of which are encompassed in this exhibition.

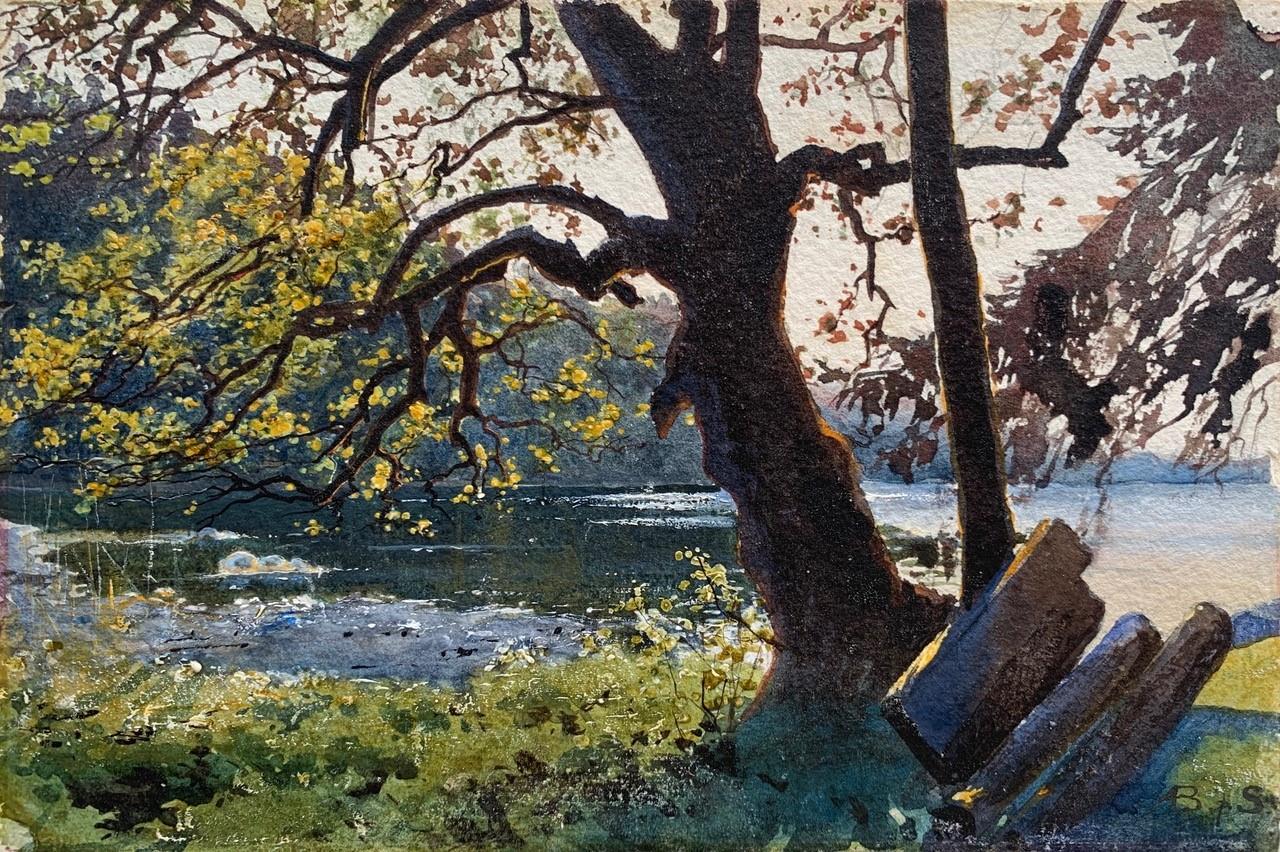

With this said, her earlier work, made pre-1900, includes studies such as the watercolour SummerLandscapefromStockholmof c.18841888 (fig. 4). Briefly enrolled at the Académie Julian in Paris in 1884, Boberg’s exposure to the academy lifestyle popular among her colleagues was short-lived. A contemporary of the Swedish impressionist painters Eva Bonnier (1857-1909) and Emma LöwstädtChadwick (1855-1932), who similarly attended the Académie Julian during the 1870s and early 1880s, Boberg was undoubtedly exposed to stylistic trends prevalent among her peers. We might assume from this that Boberg was at least familiar with the work of the impressionist painters, adopting an en plein air technique in her landscape paintings. The initials signing the work “B. AS”, suggest it was painted during her long engagement (having become engaged to

Anna Boberg (1864-1935), Summer Landscapefrom Stockholm, c.1884-1888

Watercolour and body colour on paper 15.2 x 22.6 cm

Ben Elwes Fine Art, London.

Ferdinand in 1884) and still maintaining her maiden name Scholander. It was also during this time that Boberg started working in watercolour.

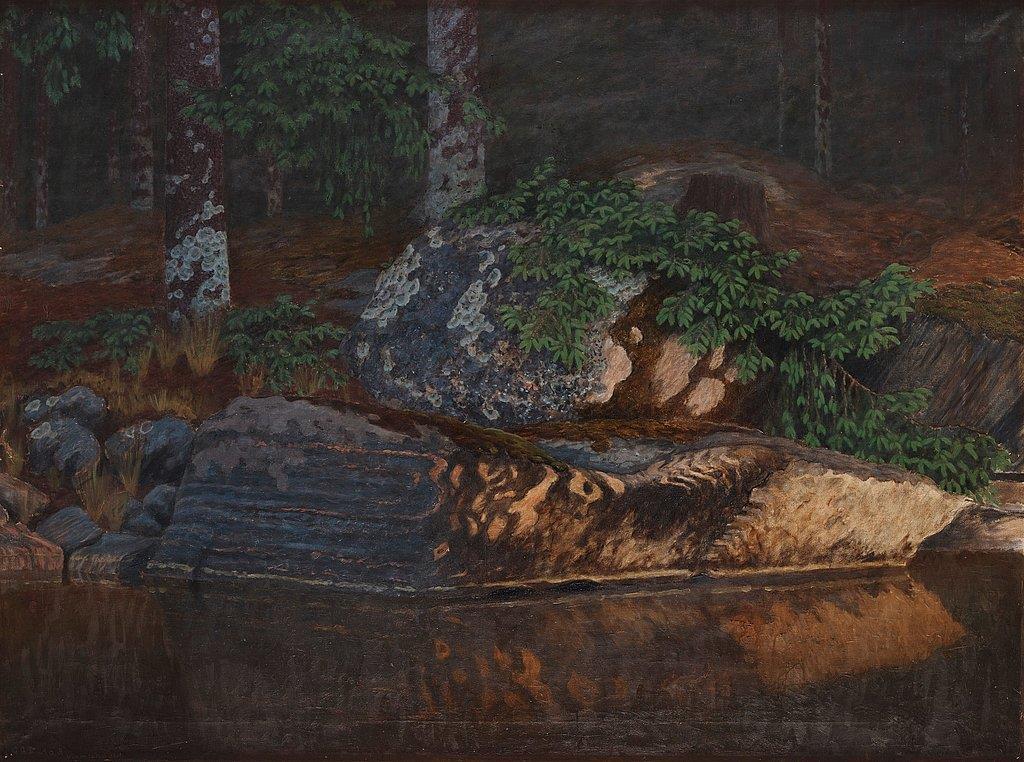

Painted during the same period, Forest Clearing, Skogsgläntan of c.1890 (fig. 5) held within the collections of the Nationalmuseum in Stockholm, exhibits a very similar palette to SummerLandscapefrom Stockholm.Shades of green and brown amass in front of the slither of light that emerges through this clearing in the forest. The mosscovered boulder at the centre of Boberg’s composition immediately recalls the studies of John Ruskin, such as InthePassofKilliecrankie of 1857 (Fitzwilliam Museum). Writing about Ruskin’s attention to the truthful study of nature and ecological observation, Edward Alexander describes how ‘he [Ruskin] discovered that the secret of capturing nature's beauty in art was not generalization but truth [… this] revelation did not transform him from a painter into a scientist. But it did show him that the reverent concern of the botanist and the geologist for natural forms must be emulated by the artist who would be truthful to nature.’9

Closer to home,SummerLandscapefromStockholmevokes the work of Swedish watercolourist Oskar Bergman (1879-1963). Bergman received no formal artistic training but is reported to have painted ‘one or even two works in a day’ taking long walks in the mornings and painting in the afternoon.10 Following the Pan-Pacific Exposition (fig. 6), in the same breath as his earlier comment on Boberg, Brinton also described Bergman’s ‘gift for decorative design.’11 Parsing out the details of the landscape, through the fluttering golden leaves against the wash of green that denotes the river, Boberg’s watercolour is evocative of the fugitive intangibility of watercolour – water sets the colour to the paper as water flows past the artist while she paints. Water appears to froth on the surface of the flowing river, as it eddies around boulders protruding from the water’s surface. Beyond the silhouetted brown leaves of the same tree, the river turns into a wash of white and blue signalling the direction of the sun. With this, unlike many of her other paintings, Boberg offers a momentary yet detailed glimpse of a suburban summer landscape. Through these earlier studies, and in comparative drawings by other watercolourists and proponents of landscape painting such as Ruskin and Bergman, we might begin to understand Boberg’s evolution as a painter, from an artist attentive to environmental details to one more largely concerned with the effects of the environment.

Watercolour on paper, 79.2 x 54.5cm.

Nationalmuseum, Stockholm.

Figure 6

A View from Lofoten

Unlike the impressionist penchant for showing a ‘tiny fragment of time, an instant disconnected from any other, the isolated moment rather than the progression of time,’ Boberg’s work instead coheres multiple moments of time, often between the “golden hour” and twilight.12 By 1915, when the art critic John D. Barry wrote following the Pan-Pacific Exposition, he recorded how ‘She’s not a servile copyist. […] she wants us to realize her purpose, which is to catch the effects of light and shade.’13 Thick daubes of paint build layers into the surface of the mountain in Boberg’s View from Lofoten (fig. 7). Long, drawn out strokes from a palette knife drag thick yellow paint, tinged with pink, down the side of the mountain, basking in the Arctic sunlight. Pink, purple, green, and blue shadows define the crevices in the rock and the rockface turned away against the sun. This same palette is mirrored in the sky above. Only the snow in the foreground gives any indication of time of year, perhaps that of early Spring where the snow has just begun to thaw. That moment between light and dark also appears to manifest itself. We might assume the painting is that of the sun rising in the morning, but it might similarly be that of the sun setting, that previously mentioned moment between the golden hour and twilight. In contrast to the instantaneity of impressionism described by Charles Baudelaire as ‘the ephemeral, the fugitive, the contingent,’ Boberg’s Arctic offers a closer, more intimate insight into the fleetingness and coalescence of light and time.14

Anna Boberg (1864-1935)

ViewfromLofoten Oil on canvas

45 x 60cm

Ben Elwes Fine Art, London.

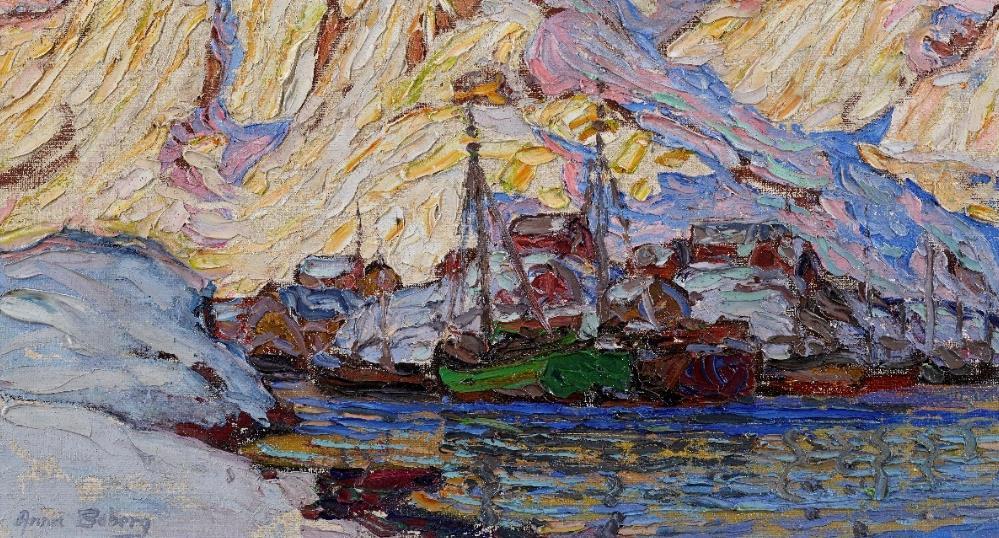

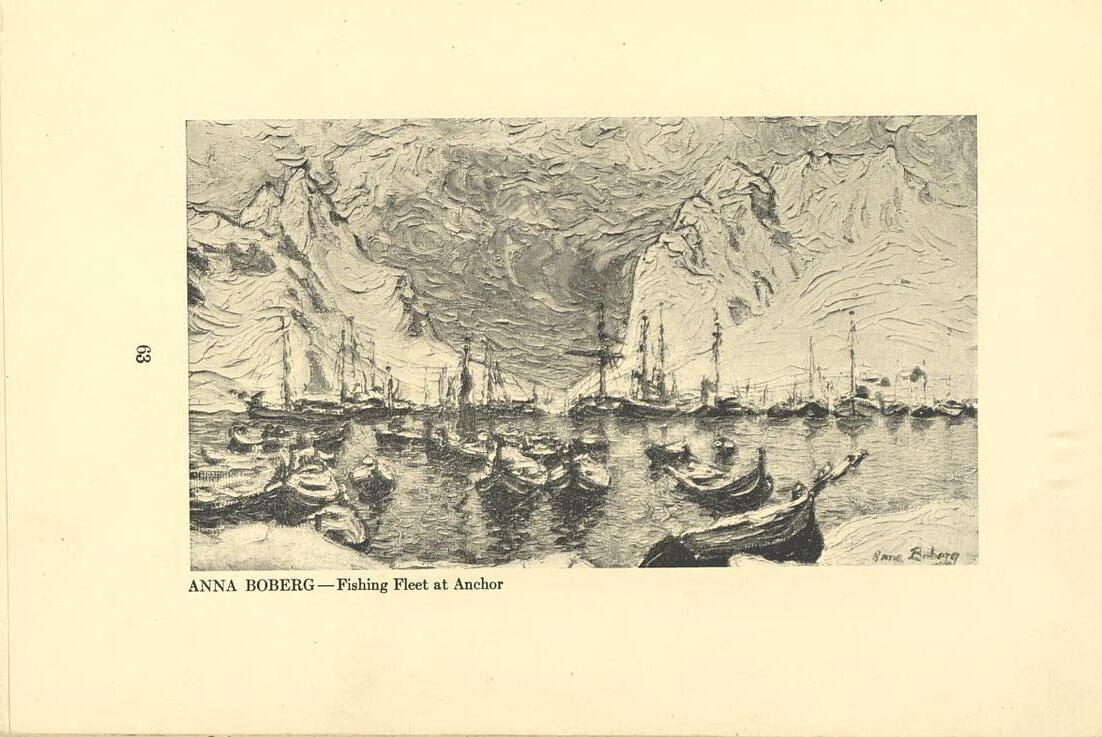

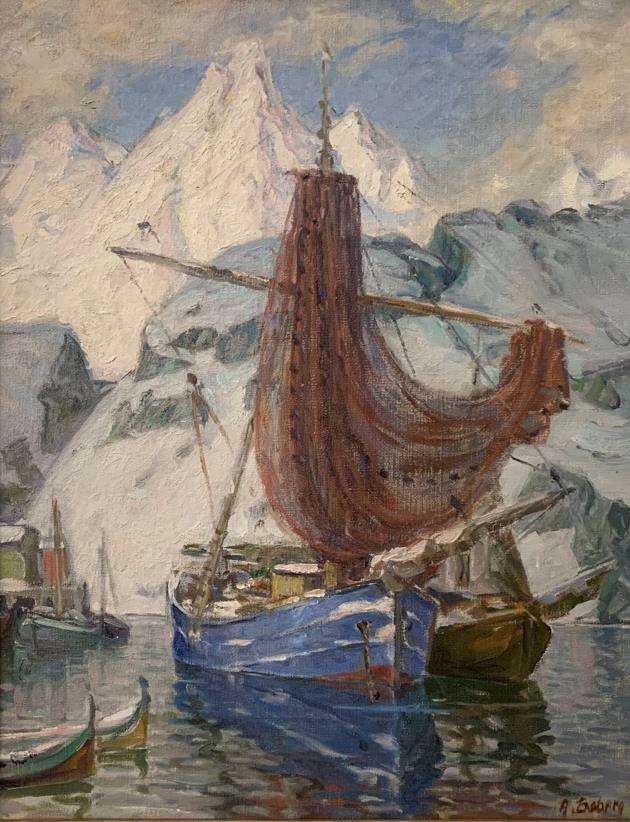

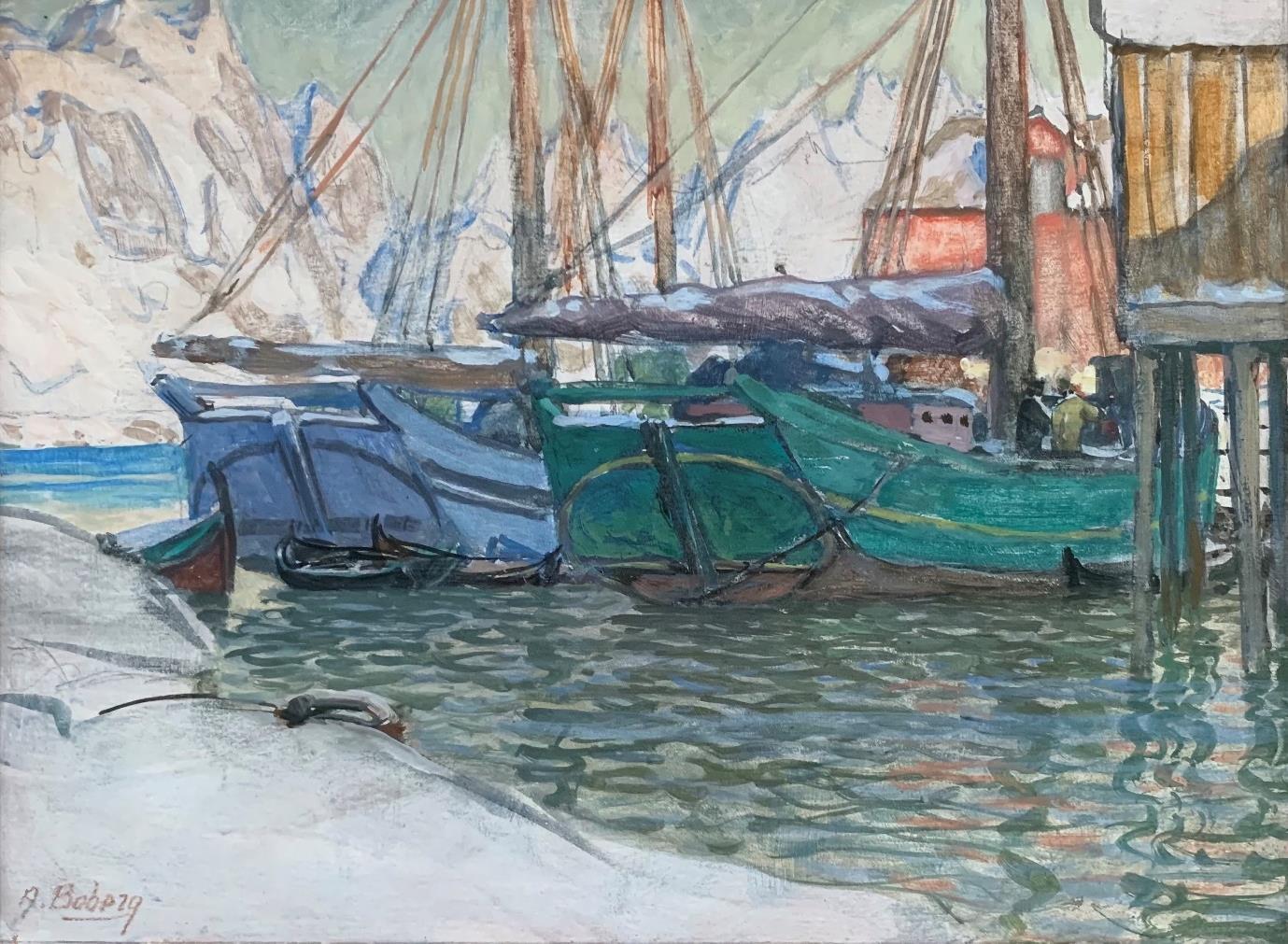

Boberg’s Lofoten landscapes were first presented at the Parisian Galerie des Artistes Modernes in 1905 and later at numerous iterations of the Venice Biennale, bringing her international recognition.15 From 1912 to 1913, Boberg was sole woman exhibitor in the Exhibition of ContemporaryScandinavianArt , curated by Brinton to tour the United States. While only exhibiting seven paintings, there were reported to be over ‘four hundred small sketches in a fireproof vault in Stockholm, carefully preserved not only for their artistic value, but also for the accuracy of detail which make them historically valuable.’16 These included scenes from throughout Boberg’s travels as well as of the first decade spent painting in Lofoten. A similarly thickly-painted view of the harbour to ViewfromLofotenis Boberg’sFishingFleetatAnchor of pre-1916 (fig. 8), which was among those paintings exhibited in The Swedish Art Exhibition of 1916, which toured the US following the conclusion of the Pan-Pacific Exposition. The historiography of Nordic, especially Swedish, exhibitions in the United States is of particular importance in understanding the ways in which Boberg’s work was historically framed and presented on an international stage.

Figure 8

Anna Boberg (1864-1935) FishingFleetatAnchor

From the catalogue for The Swedish Art Exhibition, 1916.

Writing for the 1912 catalogue, Brinton described 'those huge mountains rising out of the sea, surrounded by fleets of fishing boats’ that characterised Boberg’s paintings.17 Travelling up into the mountains during the summer, in the area surrounding Grundfjord, the Bobergs built a temporary wooden structure to keep them dry. ‘We’d had enough of the tourists,’ wrote Boberg, and so they set off to find ‘the ideal spot for Arctic summer fun.’18 An isolated spot for bathing, fishing, berry picking, and exploring with their boat, Astrup Larsen further described how ‘the hut had been placed so that a mountain shut off the sun during the short northern night, which is but a paler day with mists as soft as dove’s wings.’19 A soft mist, as alluded to by Astrup Larsen, appears to hang over the lower rocky ranges of the mountain in her painting Summer(fig. 9). Rolling grass hills wind their way to and from Vågakallen, one of Lofoten’s tallest mountains. Local mountains become identifiable features within Boberg’s paintings, they act as a constant backdrop to her Arctic landscapes. For example, not only does the expansive Vågakallen appear in several works, so does Fløya and Store Molla. InArcticMidsummerNight(fig. 10), Boberg has descended the grassy slopes seen in Summer , and instead paints from the shoreline. The mountain has turned red, almost vermillion, from the fading, but not completely absent summer sunshine. The inlet of the fjord reflects the mountain and sky above.

Moving seamlessly between pastel hues, monotone shades, and vibrant tones, Boberg builds to a crescendo of colour that reverberates across the vivid hulls of the fishing vessels and the surface of the surrounding water. Yet, despite the shifting colours upon the changing tides, the one constant presence throughout her scenes of the Svolvær harbour is the vast mountain of Fløya, seen in FromMy Island and View from Lofoten (fig. 7) In her diary, Boberg wrote, ‘Mountain islands rose-up high, rose right up and down in a silver mist.’20 Her husband further elaborated in his own writing, Minnesanteckningar(MemoryNotes) , that upon seeing the Lofoten mountain ranges, ‘Anna was completely astonished and seduced - she just sank into a silent adoration: - here I have been before, here I belong, this I have felt before, this is mine, here I must be, and here I must return.’21 While there are several isolated studies of the mountains and scenes of the harbour painted from high-up on the mountain slopes, paintings such as ViewfromLofoten(fig. 7), despite the absence of any boats, provide an important topographical framing for appreciating Boberg’s scenes of the harbour, boats and ships, activities, and fisheries that populated the coastline. It further evokes Astrup Larsen’s description of there being ‘cliffs like jagged opals in the sun, a sea that rivals the wine-coloured ocean of Homer in its deep reds and purples, quiet waters gathering reflections of the fishingboats in pools of iridescent color.’22

Although we are unable to date most of Boberg’s paintings, we do know that she was painting during the ‘renaissance’ of small boats, and simple line-fishing, which reached similar peak levels in the 1920s as in the late nineteenth century.24 Not only was Boberg painting during the heyday of the lofotfisket(Lofoten fishery), but also one of its last flourishes. In her diaries, she records the modernisation of this local industry:

Who, at the time of my earlier visits to Lofoten, could imagine that this millennial fairy-tale would soon be at an end! That the power of the motor would in a staggeringly short time end tradition. The slow, hammering of the oars was replaced by the engine’s rapid bangs, pure sailing was over forever. The fishing boat and its bigger sister, the hunting vessel, will survive only as museum objects.25

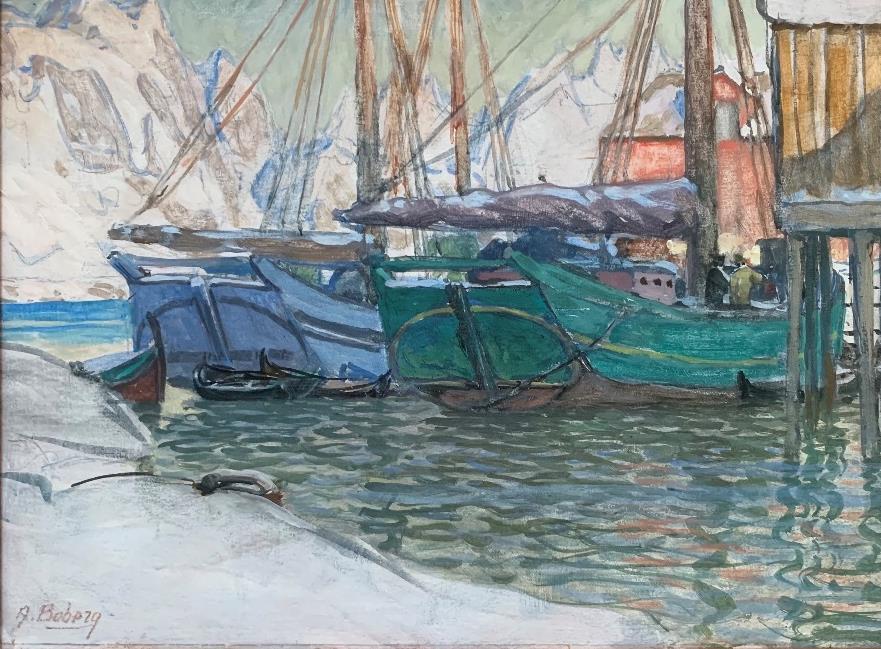

There are clear distinctions between the boats in Boberg’s paintings; and the blue and green sterns in FishingBoats(fig. 11) evoke Boberg’s line of the ‘hunting vessel’ also seen in the heavily-loaded and perhaps sea-bound TheBlueBoatof 1925-1929 (fig. 12) at the Nasjonalmuseet in Oslo and in Fishing Boats, Lofoten, Norway (fig. 13), recently acquired by the Krannert Art Museum, University of Illinois, UrbanaChampaign. Where these two paintings showcase the ‘hunting vessel’ resplendent with billowing sails, the unusual close cropping of the composition in FishingBoats , with the empty masts extending beyond the picture plane go further to suggest their impressive scale. Seen together, these three paintings provide a narrative of scale and movement, of the ships moored in the harbour, and travelling to and from the open sea. Astrup Larsen writes that ‘The fishing-boats, as Anna Boberg paints them, are personalities, eloquent with stories.’26 Memorialising the Lofoten fishery was also prevalent in the work of nineteenth-century Norwegian painters Otto Sinding, Adelsteen Normann, and Gunnar Berg, all of whom favoured the continued presence of traditional vessels within the landscape. Boberg’s vibrant landscapes and seascapes, including Fishing Boats , similarly participate in this cultural geographic shift.

Figure 11

Anna Boberg (1864-1935), Fishing Boats,Lofoten,Norway , gouache on board, 30 x 39.8cm.

Ben Elwes Fine Art, London.

Figure 12 (Left)

Anna Boberg (1864-1935), TheBlueBoat,1925-1929, oil on canvas, 59.5 x 53cm. Nasjonalmuseet, Oslo, Norway, NG.M.01871.

Figure 13 (Right)

Anna Boberg (1864-1935), FishingBoat,Lofoten,Norway , oil on canvas, 46.5 x 36.4 cm. Krannert Art Museum, University of Illinois, Urbana-Champaign

Local fishermen were not entirely opposed to modern developments, but nevertheless the push against tradition led to repeated confrontation between ‘fishermen who used traditional open boats and modern entrepreneurs and capitalist shipowners.’27 Until the 1860s, the Nordland boat had been widely used by Norwegian fisherman, rowing and sailing north and south of Lofoten. Often made of either pine or spruce, these boats were painted with thick bands of colour encircling the top. In contrast, the larger fishing vessels were often blocked out in complimentary shades of yellow, blue, red, and green. Despite the introduction of modernised boats toward the end of the nineteenth century, the open-topped Nordland boat remained a common favourite among Lofoten fishermen. Paintings including Boberg’s ViewfromLofoten(fig. 14) depict the fishing fleet, moored in the harbour, bathed in the light of the golden hour. With the setting of the sun, pink reflections ripple across the fjord, casting the boats in a red silhouette. The mountains, which are also visible in the other

painting titled, ViewfromLofoten(fig. 7), take on a very different form as misty yellows shape the ridges and crevices of the mountain.

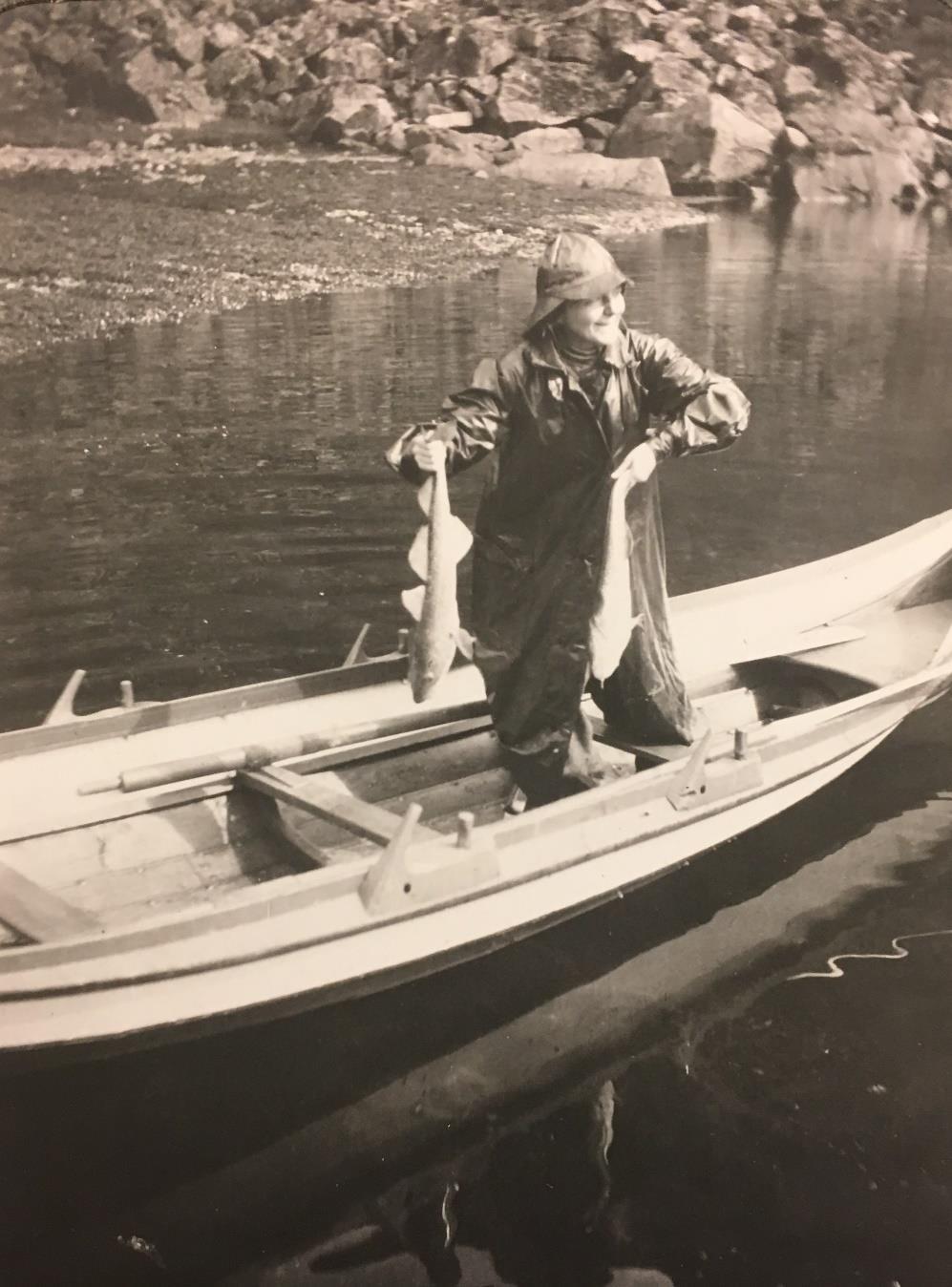

This commitment to the Lofoten lifestyle by Boberg also manifested itself in the purchasing of her own little boat, the Puttan , which she managed and used herself, and allowed for fishing and painting expeditions, in and around the fjords. Boberg devised her own ‘special type of palette and easel, which can be strapped to her person, so that she can paint on a rocking boat and miss no shifting play of sun and wind on the churning sea.’28 She was not alone in using the boat as a painterly tool; the Swedish landscape painter Josefina Holmlund was known to have painted from aboard a rowing boat, while CharlesFrancois Daubigny devised a floating studio that featured in a series of etchings titledTheBoatTrip , and Claude Monet built a studio boat in the mid-1870s allowing him to paint from the perspective of the waterline. In her writing, Boberg also distinguished herself ‘as a passionate amateur fisherman [who] went out in a small boat to try and catch the cod with a line and hook,’ distinct from the prevailing lofotfisket . 29 While she removes herself from her paintings, several family photographs, many taken by her husband, do show Boberg dressed in waterproof overalls rowing and catching fish (fig. 15). This photograph was taken from their hut on Grundfjord, which Boberg described as a place where ‘For fishermen, what an eldorado! Cod and flounder in the fjord, trout and salmon in the rapids and lake.’30

15

FishingBoatsis also particularly evocative of other works such as Egon Schiele’s HafenvonTriest,HarbourofTrieste,of 1907 which was last seen at Christie’s in 2006. Contemporaneous with Boberg’s early trips to the Lofoten Islands, Schiele’s painting abstracts the reflections of the vividly coloured hulls and masts into swirling patterns upon the water’s surface. Where in Boberg’s painting the reflected colours of the Nordland boats rest in a mismatch pattern upon gently moving waves, Schiele scores the wet paint with a pencil or the opposite end of a paintbrush. During a brief stint in prison in 1912, Schiele wrote in his prison journal: ‘I dreamt of Trieste, of the sea, of open space. Longing, oh longing! For comfort I painted myself a ship, colourful and big-bellied, like those that rock back and forth on the Adriatic. In it longing and fantasy can sail over the sea, far out to distant islands where jewel-like birds glide and sing among incredible trees. Oh sea?’31 This pan-European evocation of ships and the sea, offers possible ways of framing Boberg’s harbour and fishing scenes beyond the Arctic. While the setting of Schiele’s painting is markedly different, reflecting instead the built-up harbour of Trieste on the Adriatic coast, like Boberg, it explores the visual binaries of colour and light, framing what we can see.

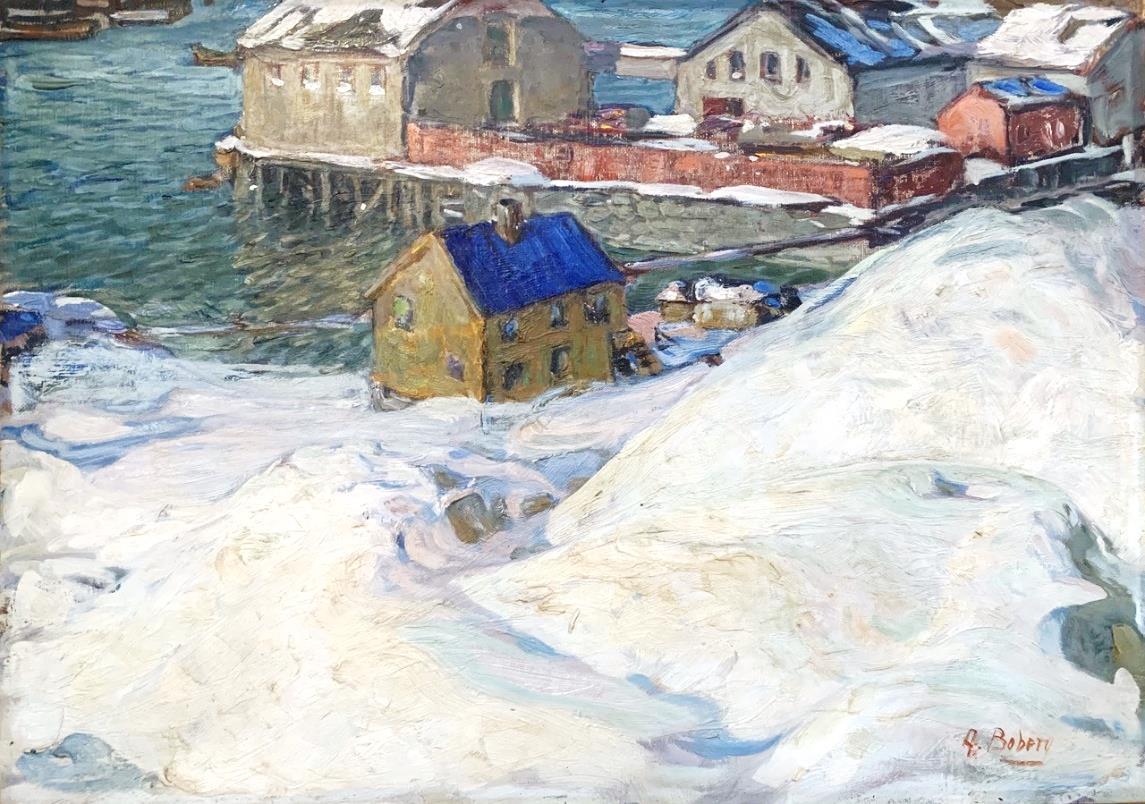

These nuances of colour also emerge in the snow occupying the foreground of TheBlueRoof(fig. 16), which is unusually limited in its colour palette. Only the shock of the yellow building and lapis blue roof disrupt the shades of pink, blue, grey, and white of this built-up coastline. Among digitised records of Boberg’s work there is only one other painting, Running before the Storm (Nationalmuseum, Stockholm), that depicts a similar, blue-roofed structure. The idea that the purple, pink, and white brushstrokes of the snow might also denote rock completely eludes the viewer; the light bouncing off the snow deflects the reality of the situation. It accounts for the ‘vibration of air inundated with light,’ as Edmond Duranty once remarked.32 The closecropped perspective, guiding the eye down the snowy slope towards the yellow house and ultimately to the water surrounding the jetty, places the viewer and, by proxy, the artist within the landscape.

The shoreline storehouse also appears in the backdrop to Fishing Boats . A salmon pink structure is visible in-between criss-crossing ropes and masts, with different angles of this same building appearing in other oil sketches by Boberg. TheBlueRoofis especially important in this regard for drawing attention to the social and cultural implications of the lofotfisket . While the exact location of the painting

is unknown, TheBlueRoofis unique for this infrastructural emphasis. Although Boberg has cropped the composition in such a way that the height and depth of the surrounding environment is obscured, the focus on the structures on the coastline contributes to the ongoing narrative of the fishing industry in many of her other Lofoten landscapes. It is likely that many of these buildings out on the jetty were storehouses for the boats coming into harbour. The yellow and blue building, the focus of Boberg’s painting, is more likely to be domestic, perhaps lived in by one of the fishermen or dock workers. These buildings likely stored herring or codfish, the former of which had driven ‘transatlantic commerce as a staple of both the European diet and the Atlantic slave trade.’33

In writing about the local fishing community, Boberg described the economic value of the catch, where with ‘larger fish your pockets are stuffed full of lovely banknotes, [and] your debts to the bank repaid.’34 Racks of drying stockfish, a product local to the area, mark the landscape to this day, and are visible in several works by Boberg, including MotiffromLofotenwhich featured alongside TheBlueRoof in the Kvinnligapionjärerexhibition at Prins Eugen Waldemarsudde in 2022 (cat. No. 31) Beyond this, factories were constructed in the area during the second half of the nineteenth century. The first herring-oil factory was constructed in Svolvær in 1898 (and the subject of a painting by Boberg); and earlier that century, the production of guano fertiliser, using fish heads and other waste, was built in Svolvær, the first of its kind in Europe. Beyond these, Boberg also painted the Whale Oil Factory (Nationalmuseum, Stockholm. NM 4278), with tall chimneys emitting plumes of smoke, suffocating the sky, and concealing the land beyond. The North Atlantic and Norwegian marine environment was at one time dominated by whaling vessels, with the Lofoten Islands up until the early twenty-first century providing most of Norway’s whale meat. While The Blue Roof does not directly represent any of these particular industries, it is important to see it as part of this series of paintings, alongside Boberg’s more prevalent scenes of fishing vessels moored in the harbour, documenting the human activities on the shoreline. Beyond the boats, which we can only glimpse at in the far-left corner of The Blue Roof , much of the commercial enterprise of fishing took place on land.

In an article published in The Studio, following the exhibition of Boberg’s work in Paris in 1905, the author wrote that her paintings represented ‘a sort of epitome of the life of the sailors of the North of

Norway: their departure with the fishing fleet, their return in storm or calm, and their arrival in some sheltered harbour.’35 Boberg’s local knowledge and intimate perspective of the Lofoten landscape allows for a more comprehensive and continuous understanding of this coastal Arctic environment to emerge than is often, historically, available. With this, Boberg’s Lofoten paintings, of which the works shown in this exhibition are wonderfully executed and indicative examples and when seen together represent a continuous scene of the Svolvær harbour, are important for underscoring the importance of this prominent Arctic and European fishing trade, Arctic landscape and climate, and artistic economy in the late nineteenth and early twentieth century.

16

Anna Boberg (1864-1935)

TheBlueRoof[Detblåtaket]

Oil on canvas

35.6 x 50cm

Ben Elwes Fine Art, London.

Dr Isabelle Gapp is an art historian who writes and teaches at the intersections of landscape painting, environmental history, and climate change around the Circumpolar North. She is an Interdisciplinary Fellow in the Department of Art History at the University of Aberdeen. Isabelle leads the British Academy-funded project From the Floe Edge and multi-grant awarded project Teaching Arctic Environments. She is the author of A Circumpolar Landscape: Art and Environment in Scandinavia and North America, 1890-1930 (Lund Humphries, 2024).

Notes

1. Christian Brinton, ImpressionsoftheArtofthePanama-PacificExposition(New York: John Lane Company, 1916), 142.

2. Eugene Neuhaus, TheGalleriesoftheExposition(San Francisco: Paul Elder & Company, 1915), 41.

3. Isabelle Gapp, ACircumpolarLandscape:ArtandEnvironmentinScandinaviaandNorth America,1890-1930(Lund Humphries, 2024).

4. Jen Rose Smith, ‘“Exceeding Beringia”: Upending universal human events and wayward transits in Arctic spaces,’ EnvironmentandPlanningD:SocietyandSpace39, no.1 (2021): 158-175. Doi: 10.1177/0263775820950745

5. Anna Boberg, Envar sitt ödes lekboll (Stockholm: Norstedts, 1934), 16. Original quote, translation by author: ”Och jag som inbillat mig förete en illusorisk anblick av en respektingivande polarforskare!”

6. Isabelle Gapp, “A Woman in the Far North: Anna Boberg and the Norwegian Glacial Landscape”, KunstogKultur104, no.2 (2021): 82-96. Doi: 10.18261/issn.1504-3029-2021-020

7. Hanna Astrup Larsen, “Anna Boberg: The Sea Painter of the North,” TheCraftsman23, no. 4 (January 1913): 448.

8. Louise Nyström, SvenskaBilder:iAnnaochFerdinandBobergsfotspårefterhundraår (Stockholm: Carlsson, 2011), 12. Original quote, translation by author: ’Var jag så bergtagen i Lofotnatur att jag blankt nekade resa hem. Jag ville stanna och måla, måla, måla.’

9. Edward Alexander, ‘Ruskin and Science,’ TheModernLanguageReview64, no.3 (1969): 508-521. Doi: 10.2307/3722043

10. Vibeke Röstorp, Oskar Bergman (18179-1963): Alifeinnature,exhibition cat, Galerie Michel Descours & Benjamin Peronnet Fine Art, Oct-Nov 2021, 28.

11. Brinton, ImpressionsoftheArtofthePanama-PacificExposition , 142.

12. Moshe Barasch, ModernTheoriesofArt,2:FromImpressionismtoKandinsky(New York: New York University Press, 1998), 54.

13. John D. Barry, ThePalaceofFineArtsandtheFrenchandItalianPavilions(San Francisco 1915), 24.

14. Charles Baudelaire, “The Painter of Modern Life,” in Selected Writings on Art and Literature,trans. P.E. Charvet (New York: Penguin, 1972), 403.

15. Boberg exhibited at the Venice Biennale in 1907, ’12, ’14, ’20, ’22, ’24, ’26, and ’28, with her work being acquired by the Galleria Internazionale di Arte Moderna, Ca’ Pesaro, Venice and the Galleria Nazionale d’Arte Moderna, Rome. For more see: Margherita d’Ayala Valva, ‘Touristic and Chauvinistic Perspectives on the Arctic in the Italian Popular Press,’ Nordlit, no.23 (2008): 371-384. Doi: 10.7557/13.1351

16. Astrup Larsen, ‘Anna Boberg: The Sea Painter of the North,’ 448.

17. Christian Brinton, ExhibitionofContemporaryScandinavianArt(New York: The American Art Galleries, 1912), 55

18. Boberg, Envarsittödeslekboll , 188. Original quote: ”Vi hade fått nog av turister […] efter idealplatsen för ett arktiskt sommarnöje.”

19. Astrup Larsen, ‘Anna Boberg: The Sea Painter of the North,’ 440.

20. Boberg, Envarsittödeslekboll,15. Original quote: ’Fjällöar hägrade högt, hägrade rätt upp och ned it ett försilvrat dis.’

21. Ferdinand Boberg as cited in Per Posti, Lofotenibilledkunstenframtil1940(Svolvær, 1991), 15. Original quote: “blev Anna fullkomligt slagen av häpnad och hänförelse – hon bara försjönk i en stilla tilbedjan: - här har jag varit förr, här hör jag hemma, det här känner jag förut, det här er mitt, här måste jag vara, hit måste jag komma tilbaka.”

22. Astrup Larsen, ‘Anna Boberg: The Sea Painter of the North,’ 446.

23. Boberg, Envarsittödeslekboll,197. Original quote: ”Sommarhav, öde hav.”

24. Isabelle Gapp, “An Arctic Impressionism? Anna Boberg and the Lofoten Islands,” in MappingImpressionistPaintinginTransnationalContexts,eds. Emily C. Burns and Alice M. Price (New York: Routledge, 2021), 90-102. Doi: 10.4324/9781003044239

25. Boberg, Envarsittödeslekboll,10. Original quote: “Vem kunde vid tidpunkten for mina tidigare vistelser i Lofoten ana att dess tusenåra saga snart skulle vara all! Makten som på svindlande kort tid bröt traditionen var motorn. Årornas långsamma hammarslag

ersattes av motorns hastiga smällar, råseglet beslogs for alltid. Båtarnas båt och hennes större syster jaegten skola överleva sig själva som museiföremål.”

26. Larsen, “Anna Boberg: The Sea Painter of the North,” 445.

27. Pal Christensen, Den Norsk-Arktiske Torsken og Verden (Lofoten: Museum Nord, 2009), 22.

28. Larsen, “Anna Boberg: The Sea Painter of the North,” 445.

29. Boberg, Envarsittödeslekboll,14. Original quote: “Som passionerad amatörfiskare hade jag gått över i en lättbåt for att dra torsk med pilk.”

30. Boberg, Envarsittödeslekboll,191. Original quote: ”För fiskare, vilket eldorado! Torsk och flundra i fjorden, laxöring och lax i fors och sjö.”

31. Egon Schiele, ‘Prison Diary, 1 May 1912,’ Christie’s. https://www.christies.com/en/lot/lot4742959

32. Edmond Duranty, TheNewPainting:ConcerningtheGroupofArtistsExhibitingatthe Durand-Ruel Galleries (1876), cited in Linda Nochlin, ed., Impressionism and PostImpressionism,1874–1904:SourcesandDocuments(Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall, 1966), 5.

33. Mark Kurlansky,Cod:ABiographyoftheFishThatChangedtheWorld(New York: Penguin, 1997), 82.

34. Boberg, Envarsittödeslekboll,13. Original quote: “Storfiske är fickorna proppfulla med dejliga banknoter, är skulden i handelsboden betald”.

35. TheStudioas cited in Eva-Charlotta Mebius, ‘“Sweden’s Greatest Artist:” The Reception of the Landscapes of Anna Boberg,’ Art Bulletin of Nationalmuseum Stockholm 27 , no.1 (2021): 94.

Exhibition Catalogue

Ben Elwes Fine Art, Summer 2024

3 June – 30 August 2024

List of illustrations:

1. Anna Boberg, Summer,c. 1911-1934

2. Anna Boberg, TheBlueRoof

3. Anna Boberg, Engabreen,SvartisenGlacier,Norway

4. Anna Boberg, ViewfromLofoten(45 x 60 cm)

5. Anna Boberg, ViewfromLofoten(30 x 45 cm)

6. Anna Boberg, SummerLandscapefromStockholm , 1884-1888

7. Anna Boberg, Fishingboats,Lofoten,Norway

8. Gustaf Fjæstad, Barrskogsinteriör

Anna Boberg (1864-1935)

Summer , c. 1911-1934

Oil on canvas

59 x 81 cm (22 1/5 x 31 4/5 in)

Signed lower right: A.Boberg

Anna Boberg (1864-1935)

TheBlueRoof[Detblåtaket]

Oil on canvas

35.6 x 50 cm (14 x 19 ¾ in)

Signed lower right: A.Boberg

Anna Boberg (1864-1935)

Engabreen,SvartisenGlacier,Norway

Oil on canvas

45 x 56 cm (17 ¾ x 22 in)

Signed lower right: A.Boberg

Private Collection

Anna Boberg (1864-1935)

Oil on canvas

45 x 60 cm (17 ¾ x 23 3/5 in)

Signed lower left: AnnaBoberg

Anna Boberg (1864-1935)

ViewfromLofoten

Oil on canvas laid on board

30 x 45 cm (11 4/5 x 17 ¾ in)

Signed lower right: AnnaBoberg

Anna Boberg (1864-1935)

SummerlandscapefromStockholm,1884-1888

Watercolour and body colour on paper

15.2 x 22.6 cm (6 x 8 9/10 in)

Signed lower right: AB–S[AnnaBoberg,född(née)Scholander]

Anna Boberg (1864-1935)

Gouache on board

30 x 39.8 cm (11 2/5 x 15 3/5 in)

Signed lower left: A.Boberg

Inscribed verso in pencil: Akterspeglar

Gustaf Fjæstad (1868-1948)

Barrskogsinteriör(Coniferforestinterior)

Oil on canvas

120 x 160 cm (47 ¼ x 63 in)

Signed and dated lower left: GAFjaestadVermland1904

Entitled on the verso

Gilt original frame with a brass plate inscribed in English: ThawintheForest