Cover:

(detail)

LakeTiticaca , 1935

Oil on canvas

176 x 240 cm

Signed lower right: AlejandroMARIOYLLANES/-Titikaka-1935

Full image reproduced above

(Illustration no. 3)

Alejandro

Signed lower left: A.M.YLLANES

(Illustration no. 6)

Cover:

(detail)

LakeTiticaca , 1935

Oil on canvas

176 x 240 cm

Signed lower right: AlejandroMARIOYLLANES/-Titikaka-1935

Full image reproduced above

(Illustration no. 3)

Alejandro

Signed lower left: A.M.YLLANES

(Illustration no. 6)

Bolivian painter and print maker Alejandro Mario Yllanes (1913-c. 1960) produced unprecedented images of the struggles and exploitation of the Aymara people, while also celebrating the bold colours and swirling energy of their folk rituals. His Andean landscapes pulse with the patterns and rhythms of traditional textile and ceramic design, and his figures possess the exaggerated musculature and distorted bodies of a people accustomed to a life of toil. Colour for Yllanes is not tied to the natural world, but instead draws on the vibrancy of native costume, the hyperbole of local legend, and effervescence of the thin mountain air. Indeed, his images encapsulate the two poles of Andean life: backbreaking labour and the myths and rituals that sustain such a precarious existence.

Working in the 1930s and 1940s, Yllanes’ artistic career follows a distinct path from conventional narratives of Bolivian art history, which centre on artistic production in the capital city of La Paz. His outlook aligns more with the radically political manifestations of indigenismo in Peru, Ecuador, and Mexico than with the milder renditions of the trend practiced by officially sanctioned artists in Bolivia. Moreover, he was among the first Latin American artists (along with such figures as Adolfo Best Maugard (18911964) in Mexico and Elena Izcue (1889-1970) in Peru) to incorporate the motifs and design practices of indigenous peoples, in this case Aymara artistic traditions, in his work. Like Best Maugard and Izcue, Yllanes was inspired by the doctrines of education reform aimed at native populations, which manifested in his powerful murals for the Warisata school, an audacious experiment in indigenous education implemented in the high Andes. Together these practices make him one of the most innovative painters in preRevolutionary Bolivia.

The history of modern art in Bolivia privileges Cecilio Guzmán de Rojas (1900-1950), who returned from Paris in 1929 and took over as Director of the Academía de Bellas Artes in La Paz in 1932. Guzmán de Rojas championed a version of indigenismo , that while elevating indigenous peoples as worthy subjects of fine arts, circumvented the socially critical and overtly political aspects of the trend and instead focused on decorative and symbolist renditions of an imagined indigenous past. Scholarly focus on artistic production at the academy left little room for figures like Yllanes whose clashes with the government and frequent absences from the country situated his work outside official narratives. His highly innovative work deserves reconsideration, however.

clashes with the government and frequent absences from the country situated his work outside official narratives. His highly innovative work deserves reconsideration, however.

Broadly defined, indigenismois a Pan-Latin American intellectual trend that denounces the political and economic exploitation of Native American populations through literary, artistic, and social projects. The Peruvian journalist José Carlos Mariátegui (1894-1930), arguably the most important Latin American philosopher of the early twentieth century, coined the term indigenismoand his writings on the subject shaped notions of the trend well beyond Peruvian borders. In his widely disseminated journal Amauta (available in most Latin American capitals as well as in Paris, Madrid, New York, and Melbourne from 1926-1930), Mariátegui envisioned the plight of Native Americans in socialist terms, aligning indigenous peoples with oppressed workers and contending that entrenched class structures prevented them from escaping poverty.

It is very likely that as a young law student in the late 1920s in Oruro, Bolivia, Yllanes read Amauta(fig. 1), discovering Mariátegui’s writings on indigenismo as well as his presentation of modern artists whose work exemplified the trend. In 1926 and 1927, Amautafeatured articles on the Mexican muralist Diego Rivera (1886-1957) and published numerous photographs of his Secretary of Public Education murals, making the journal one of the first outside of Mexico to disseminate these images.1 Rivera’s murals emphasize the exploitation of the indigenous worker by rich bosses and landowners, providing a model for a new kind of art that served a social cause. It was precisely at this moment that Yllanes withdrew from law school and took up painting, as an autodidact, to express visually the poignant social issues of his day.

Left: Amauta,año I, núm. 1 [Amautavol. 1, no. 1], September 1926. Magazine, Archivo José Carlos Mariátegui, Lima, Peru

Right: José Sabogal, Diseño de carátula de Amauta,año IV, núm. 26 [Cover design of Amautavol. 4, no. 26]

September-October 1929. Magazine, Archivo José Carlos Mariátegui, Lima, Peru

Although most of the paintings included in Yllanes’s first exhibition in Oruro in 1930 have not survived, it is evident from newspaper reproductions and the titles of the works, such as ElEspectrodelamina(The Ghost from the Mine) and La Pandilla del bizco (The Squinting Gang), that some of the paintings depicted oppressed indigenous workers from the tin mines in the Oruro region, where Yllanes had worked as a youth. Alongside these paintings, as in Diego Rivera’s courtyard of Fiestasat the Secretary of Public Education, Yllanes displayed images that portrayed Aymara myths and customs, and incorporated design motifs from the ancient culture of Tiahuanaco, leading reviewers to praise his approach as a “new style of Tiahuanacan art.”2

The Chaco War between Bolivia and Paraguay, which raged from 1932 to 1935, had a devasting impact on the indigenous population, many of whom were forced to enlist in the army. The war resulted in enormous loss of life and territory and ended in military defeat. While the war briefly interrupted Yllanes’ artistic development, he managed to travel to La Paz in 1933 where he held a successful exhibition of “Arte Aymara” at the CírculoMilitar . He was photographed at the exhibition with the likes of Bolivian indigenist sculptor Marina Nuñez del Prado (1910-1995) and eminent art critic Rigoberto Villarroel Claure (b. 1890), major players in the La Paz art scene. Claure also reviewed the exhibition writing, “It is the expression of a world chained to suffering...”3 In the exhibition were many of the works Yllanes had exhibited in Oruro, including his scathing indictments of the abuses against indigenous workers as well as his depictions of the myths and decorative motifs of the Aymara people, which critics again lauded as “new, authentic elements from architectural and ceramic ornamentation.”4 The exhibition was the first to present socially critical indigenist paintings in La Paz and coincided with the beginnings of a period of leftist resistance, political upheaval, and instability that ultimately spawned the Bolivian National Revolution in 1952.

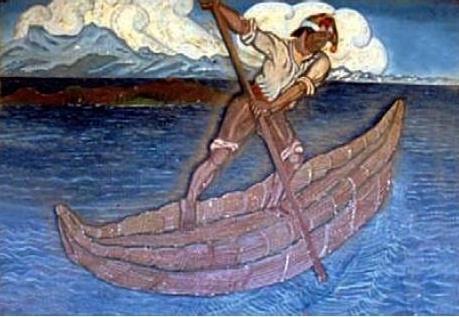

Following his exhibition in La Paz, Yllanes left for a post in the Lake Titicaca region teaching vocational courses at the Warisata School from 1933 to 1935, where he also painted a series of murals. Setting an extraordinary precedent in the history of Latin American education reform, the Warisata School was an experimental project that flourished between 1931 and 1940. A collaborative endeavour between itinerant white educators and the Aymara peoples of the region, the school modelled itself on traditional practices of reciprocity and egalitarianism (ayni), and challenged overtly racist assumptions that indigenous peoples were incapable of intellectual pursuits.5 Yllanes painted eighteen murals on the school walls depicting the life and daily activities of the Aymara that emphasized productivity and selfsufficiency. Scenes included oarsmen in reed boats on Lake Titicaca (fig. 2),

LakeTiticaca , 1935

Oil on canvas

176 x 240 cm

Signed lower right: AlejandroMARIOYLLANES/-Titikaka-1935

(Illustration no. 3)

farmers ploughing and sowing their fields, leatherworkers, and renditions of the history and culture of the region. One critic, noting the power of the images, wrote that the artist “turns his brush into an axe,” and observed that Yllanes abandoned the curve to adopt the rectilinear planes characteristic of native artistic traditions.6 News of the Warisata school’s successful educational experiment spread to Peru, Mexico, and the United States, who sent delegations of reformers to observe and learn from its practices. Just as the school was gaining international prestige, however, it became a source of contention among conservative politicians and educators in Bolivia. In 1942, years after Yllanes’s departure, assimilationists shut down the school and destroyed the murals.

Blamed for the devastating Chaco War, President José Luis Tejada Sorzano (1882-1938) was overthrown in a military coup on May 17, 1936, and Colonel José David Toro Ruilova (1898-1977) took over as de facto president. Yllanes, whose leftist visual critiques and association with the progressive Warisata school made him a target, was sent into exile in the Amazon for nearly a year. He then fled the turbulent political environment in Bolivia, spending the next several years traveling and furthering his artistic education in Chile, Argentina, and Mexico. In Buenos Aires, where he held an individual exhibition in 1938, he most likely saw the poignant work of social realist artist Antonio Berni (1905-1981) who dominated the art scene there in the late 1930s. But it was his in-person encounter with the public murals in Mexico City that made the greatest impression on the Bolivian artist. In an interview upon his return, Yllanes extolled Rivera, but proclaimed that he most admired the work of José Clemente Orozco (1883-1949) whose expressionist style accentuated his social critique. 8

In 1940, Yllanes ventured back to Bolivia, holding an exhibition, sponsored by the Ministry of Education, of sixteen large-scale oil paintings that depicted the life and working conditions of the Aymara in January 1941 at the Palacio Municipal. The short-lived revolutionary journal, Inti , praised the exhibition and labelled Yllanes’s imagery as “proletarianized indigenist painting.”9 The reviewer also commented on the obvious influence of Rivera, and elevated Yllanes’s work above the “timid” and “delicate” painting of Guzmán de Rojas. Another review noted that the show was one of the most popular art exhibitions ever presented in La Paz.10 But it was precisely the popularity of the exhibition and the revolutionary content of the images that roused the suspicions of the far right, who seem to have surreptitiously pressured the government to demand that Yllanes remove his works from the Palacio Municipal and close the exhibition early. This blatant censorship of Yllanes’s exhibition provoked an uproar in the press, with many defending the artist’s right to freedom of expression and blaming “gamonalista” culture (culture of the large land owners) for the closure.11

Yllanes continued to live and work in La Paz until 1944 when he held another exhibition of prints at the Salón del Departamento de Cooperación Intelectual (Salon of the Department of Intellectual Cooperation) that once again garnered a great deal of attention in press. With a solid body of work and several successful exhibitions under his belt, Yllanes set out on an international tour in 1945, organizing exhibitions in Peru (Cuzco, Puno, Arequipa, and Lima), Ecuador, and Mexico. Since he served as a Cultural Representative of the Bolivian Embassy when he arrived in Mexico, at this juncture Yllanes seems to have had the support of Bolivian government. In 1945 the beleaguered Villarroel administration, in an attempt to build support among the indigenous population, created the National Indigenous Congress to address the many abuses against Aymara and Quechua peoples in Bolivia. While never fully enacted or enforced, this pro-indigenous climate most likely improved official attitudes towards the artist.

In 1946 Yllanes held one of his most important, and ultimately last, exhibitions at the Palacio de Bellas Artes in Mexico City. The exhibition included sixteen large-scale paintings and twenty woodblock prints. Among the paintings in the exhibition were overtly critical pieces such as EstañoMaldito(Damned Tin) (fig. 3), TragediadelPongo(Tragedy of the Indigenous Worker) (fig. 4), VivalaGuerra(Long Live the War) (pictured p. 3), and Santo(Saint), as well as pictures of everyday life and traditional customs such as Balsero de Titicaca(Punter on Lake Titicaca) (fig. 2),WakhayKhusillo(Huaca and Kusillo loosely translates as sacred object and Andean clown) (pictured p. 36) and WirakhochaDanzante(Dance of the Creator Deity). Diego Rivera wrote the Preface to the exhibition catalogue, which also included endorsements from Orozco and Siqueiros. The numerous reviews in the Mexican press lauded Yllanes’s work, admiring the similarity in content and approach to that of the muralists.

Finally, in 1946 Yllanes arrived in New York City. The mid-1940s was a moment of intense political Pan-Americanism aimed at promoting hemispheric solidarity, which prompted many U.S. institutions to take a special interest in collecting and exhibiting Latin American art and created opportunities for artists to expand their networks. In New York Yllanes applied for and received a John Simon Guggenheim Memorial Foundation Grant, but that’s where the trail goes cold. Yllanes never claimed his grant funding, believed to be around $2,500, and the paintings he had carried with him across the Americas remained in the hands of a friend in New York. He is not known to have ever exhibited his work again. As a result of the abrupt end to his promising career, Yllanes’ story has been mostly omitted from the history of Latin American art. The rediscovery of Yllanes’s archive and the iconography of his later works demonstrates that Bolivian indigenismowas much more significant than previously imagined.

collection (Illustration no. 7)

Dr Michele Greet is Professor of modern Latin American art history at George Mason University and Director of the Art History program. She is author of Transatlantic Encounters: Latin American Artists in Paris between the Wars, 1918-1939 (Yale University Press: 2018) and Beyond National Identity: Pictorial Indigenism as a ModernistStrategyinAndean Art,1920-1960 (Penn State University Press: 2009). She is co-editor, with Gina McDaniel Tarver, of the anthology Art Museums of Latin America: Structuring Representation (Routledge: 2018). She has written exhibition catalogue essays on modern Latin American art for MoMA (New York), Fundación Juan March (Madrid), Museu de Arte de São Paulo, El Museo del Palacio de Bellas Artes (Mexico City), Los Angeles County Museum of Art, and El Museo del Barrio (New York). She is currently working on a book entitled Abstraction in theAndes, 1950-1970 with the support of a National Endowment for the Humanities fellowship.

1. Víctor Raúl Haya de la Torre, “Diego Rivera,” Amauta1: 4, 1926. Esteban Pavletich, “Diego Rivera: El artista de una clase,” Amauta1: 5, 1927: 5-9.

2. “estilo nuevo del arte tiahuanacota” “La exposición del artista Illanes,” LaCrónica(Oruro), Aug. 1, 1930.

3. R. Villarroel Claure, “Un pintor original,” ElDiario , Sept. 12, 1933.

4. “nuevos elementos, autenticos, de ornamentacion para la arquitectura, la cermica” “La Exposicion Illanes,” ElDiario , Sept. 15, 1933

5. Brooke Larson, “Warisata: A Historical Footnote,” ReVista: Harvard Review of Latin America , Fall 2011, XI: 1, https://revista.drclas.harvard.edu/warisata/

6. “Un Formidable Ensayo Educacional: Visita la Escuela indigenal de Hurizata,” Feb. 1, 1934.

7. Alardo Prats, “Pintura de la Nueva Bolivia: La obra fascinatne y dramatica de Alejandro Mario Yllanes,” Hoy, July 3, 1936: 62.

8. “Mario Illanes Estuvo en Mexico, Chile y la Argentina,” Inti , Aug. 2, 1940.

9. “pintura indigenista proletarizada” “El Arte Revolucionario de M.A. Illanes,” Inti Feb. 11, 1941.

10. “Movimiento de la Elite Popular para ver la exposición pictórica de Mario Illnes,” La Crónica,Feb. 12, 1941

11. Inti , Feb. 15, 1941

(Illustration no. 33)

(Illustration no. 9)

The title of the current exhibition at Ben Elwes Fine Art in London, perfectly expresses the two great passions of Alejandro Mario Yllanes, a Bolivian expressionist painter and printmaker, for whom art and politics were inextricably linked. Although largely forgotten now, Yllanes led a remarkable and, in some respects, mysterious life. A simple summary of this life would read as follows:

Born in Oruro in 1913 to an Aymara Indian mother, Yllanes was orphaned in 1925. He worked in the mines to pay for his education, initially studying law before abandoning this for art. He held his first exhibition in 1930 and continued to work in Bolivia throughout the decade. In the 1940s his world expanded as he travelled to Peru, Ecuador and Mexico, exhibiting his art to great acclaim. He felt a strong artistic and political affinity with the Mexican muralists such as Diego Rivera (1886-1957), who considered Yllanes one of America’s great original painters. In 1946 Yllanes emigrated to the United States. Two years later he was awarded a Guggenheim Foundation Grant for a proposed project of studying the art of North American Indians, but he never collected the funds. After this date, his whereabouts are uncertain and the date and circumstances of his death unknown. Some sources claim he died in 1960 but there is no evidence to prove that is the case.

To these simple biographical details one can add two important facts that give Yllanes’ life and art greater context and complexity. Firstly, he was selftaught. He lacked formal training, but that only served to liberate him from conventional aesthetic restraints. Instead of drawing on traditional forms of popular art, he created a personal artistic language that was original, passionate and confrontational, the expression of a man who was authentic, spiritual and uncompromising. “He is his own man. There’s nothing derivative about his art. He has something all of his own which will take him far,” wrote Jaime Molina, a Bolivian writer, in 1933.1

Secondly, being of Aymara descent, Yllanes dedicated his life to reviving and reinstating the culture and independence of the Aymara people who lived in the Highlands of Bolivia. The combination of these two factors resulted in some extraordinary works of art: monochrome engravings of sombre intensity as well as exuberant large-scale canvases of explosive colour. Much of his oeuvre either extolled the virtues of the traditional agrarian way of life of the Aymara or showed their violent struggle against the authorities. In that way, Yllanes aimed to inspire impassioned resistance in his people and challenge their relentless oppression and exploitation at the hands of the elite. As such, Yllanes was considered an insurgent whose art was viewed as a call to arms. Inevitably, that led to a life of struggle with the authorities, but it was a struggle Yllanes never shirked from.

Contemporary sources help construct a biography for Yllanes. They include many newspaper articles and the occasional interview with the artist, the most insightful of which was conducted by the writer Alardo Prats in 1946 for Hoynewspaper in Mexico City.2 To that material, we can add the views of Carlos Salazar Mostajo (1916-2004), a social poet who was involved in a ground-breaking project at Warisata with Yllanes in 1933-35, published in La pintura contemporánea de Bolivia3 More recently, an important retrospective of the artist took place in 1992 at Bard College in Annandaleon-Hudson, New York: BeingRediscovered:TheSpanishConquestfromthe Amer-IndianPointofView.AndeanCultureandtheLifeofAlejandroMario Yllanes(curated by Linda Weintraub).4 In 2016, the Martin du Louvre Gallery, Paris published a catalogue raisonné entitled MarioAlejandroYllanes(19131946) with an essay, “Discovering Mario Alejandro Yllanes,” by Victoria Combalía. All these sources allow us to add greater detail to the simple sketch of Yllanes’ life set out above.5

Yllanes’6 birth place, Oruro, the capital of the province of Cercado, Bolivia, is known mostly for its tin mines, which were discovered in nearby Potosí in 1900, as well as its annual carnival. Both were to feature strongly in Yllanes’ art. He was born to a poor family. His father was believed to be of mixed race, and his mother was Aymara, who instilled in her son the awareness that he belonged to a vanishing race.7 His parents died in 1925, leaving Yllanes and his brothers to be raised in one of Oruro’s orphanages. Working hard as a manual labourer in the mines, he was later promoted to wages

clerk. In that way, he was able to pay to attend the Bolivar College in Oruro, where he enrolled to study Law. In 1930, Yllanes quit school to become an artist, encouraged by his history teacher, Luis Bullain. He worked hard to teach himself the necessary technical skills. A rare description of the aspiring artist by an old school friend, R. Salamanca Lafuente, suggests that Yllanes had found his true vocation:

We lived with Mario Alejandro Illanes practically from childhood on. He was a poor, Bohemian fellow; an ironically sentimental poet; neurasthenic; lazy; a bad pupil; altogether an artist.8

On 19 August 1930, Yllanes had a one man show at the Club Oruro under the auspices of the Rotary Club and the National Festivities Committee. The exhibition included 28 paintings, among them ElEspectrodelaMina(The SpectreoftheMine) , which reflected the artist’s own personal experiences working in the mines. The show also included works that showed Yllanes’ interest in returning to his roots by inventing a “tihuanacota” style, based on Bolivia’s pre-Hispanic civilization.9 His choice of dramatic subjects, depicted with an expressive realism, showed him to be an original voice in Bolivian art. The show generally garnered positive reviews and was even extended due to the high level of interest. The press hailed Yllanes as a trailblazer with a promising future and reported that several works were acquired by wellknown local gentlemen.10 His presence there is documented in a photograph with an assembled group of artists and intellectuals (fig. 1).

Yllanes’ artistic activities in the years following the exhibition were set against the backdrop of the Chaco War, waged between Bolivia and Paraguay from 1932 to 1935.11 Many of the Aymara were drafted into the army to serve on the frontlines where casualties were high. Yllanes was himself a machine-gunner according to a Peruvian newspaper.12 Bolivia’s defeat led to a full-scale revolution, with the emergence of numerous revolutionary parties as the traditional political system collapsed. Among them was the “Youths of the Chaco Generation”, young intellectuals who campaigned to end the exploitation of the native population, a cause with which Yllanes identified even if we have no information on what specific political activities he may have been involved in.

Despite the war, Yllanes held an exhibition in September 1933 in La Paz under the auspices of the CírculoMilitar- a civil and mutual association founded on June 30, 1881, on the initiative of Coronel Mayor Nicolás Levalle. The show included several of the works from the 1930 Oruro exhibition and their strong political content elicited equally strong responses. The Bolivian poet Ricardo Jaimes Freyre (1868-1933) commented that “Yllanes will either be one of the greatest Bolivian artists or worse of all time. Certainly Yllanes does not admit things in between.” 13 Jaime Molina had a less ambivalent response:

“I have just seen a group of canvases by Illanes. And in all sincerity I have to admit that they have made a strong impression on me. In this young man – almost an adolescent – there is a painter, a great and genuine painter […] Of course, he is self-taught. He paints because he paints just as the bird sings because it sings. […] We are in the presence of an eaglet that is about to take wing on his first big flight. Let us salute in him a great painter of the future.”14

From 1933 to 1935, Yllanes was involved in an important project at a new school in Warisata, which was founded in 1931 by the Aymara leader, Avelino Siñani, and creole educator, Elizardo Pérez (1892-1980). Situated near Lake Titicaca in the Altiplano, the school developed an educational program that celebrated the indigenismo movement and taught self-sustainment and economic growth, with the aim of raising the Aymara to a higher status. As such, it was to become a model throughout Latin America in progressive education. At Warisata, Yllanes’ revolutionary interests would have developed further through contact with the radical teachers there, many of whom were members of the PM (Partido de la Izquierda), a new party based on Marxist-Leninist principles.

Yllanes painted 18 large murals for the school (measuring 5x3m and 6x5m), which show the Aymara going about their daily lives, engaged in various agricultural activities. Surviving photographic documentation of the murals shows the Aymara depicted as noble and dignified, rather than exhausted and submissive. As the scholar Joachim Schroeder noted, “Yllanesforced theIndianstudent-bodytoseethemselvesaspowerfulfigures,makingthem awareofthecausesandtheconsequencesofoppression.”16 The murals attracted both praise and criticism for the artist’s self-taught technique and controversial subject matter. Schroeder, for example, commented how the Yllanes’ “coarsestyle”was the result of both the artist’s lack of training and his originality: “his defiant wish was to create an art that, like its subject, was liberated from the Spanish and proud of its Indian past. Its goal was to eradicate forever the feudal lordships and its method was to give a voice to the people.”

In 1934, the committee of the Bolivian Ministry of Education and Ambassadors of Mexico and Colombia visited Warisata to see Yllanes’ murals. In 1935, he was named Exemplary Professor for his work there, although in that same year he left Warisata, according to Salazar Mostajo, because he had by then acquired a greater knowledge of the aesthetic and technical aspects of painting.17 The school was later shut down by Bolivia’s oligarchic powers and in 1936 Yllanes’ murals destroyed because, in the words of the artist, “the instigators of this destructions did not like that I depicted the life of the hacienda owner and its relation with the life of the Indian.” 18

After Bolivia’s defeat in the Chaco War, Salamanca’s government was overthrown and in 1936 a military junta headed by Colonel David Toro seized control. Toro oversaw an elitist regime which viewed the Indians as culturally backward and in need of civilizing. In retaliation for Yllanes’ participation in the Warisata experiment, he was exiled by Toro to the forests of Amazona for a year. Of that experience, Yllanes said:

“There I was lost for a year, living among savages, hunting beasts, and defending myself as I could from all the dangers. In reality, General Toro did me a great favour because my exile in the jungle contributed very much to help my eyes get used to the brilliant tropical colours which later on I brought to my paintings.”19

This, one can see, for example, in a pair of large-scale paintings executed in 1937 shortly after Yllanes’ return from exile: WakhaThokhoriarando , which depicts an agrarian dance that pays homage to the gods, and Wakha y Khusillo , in which men in costume imitate the movements of bulls as they plough the earth (fig. 2). It was that type of monumental painting, in oil on burlap, that stands as Yllanes’ greatest artistic achievement. The sheer scale of such works allowed the artist to communicate his message with great power and authority. In Salazar Mostajo’s words:

“Yllanes’ huge paintings instituted a rebellious spirit among the people. Under the name of Indigenism, Yllanes’ paintings shook the environment with a strong impact. […] The public came to see the Indian who was depicted for the first time, not only as an anecdotal figure, but as the main actor of the Bolivian drama.”20

Yllanes also worked in other media. He made powerful wood engravings, only in black and white. Many depict the daily lives of the Aymara, presenting them with dignity and sobriety. Others are darker in subject matter with symbols of death ever present and were compared in the Mexican press to prints by Francisco Goya (1746-1828) and Gustave Doré (1832-1883).21 There are also intense self-portraits that capture the artist’s striking features (fig. 3). He produced drawings, some preparatory to his engravings, others as independent creations. Of particular note are his illustrations of Bolivian and international intellectuals for ‘Notes on History’ in La Prensa , a left-wing Bolivian newspaper.22 Generally, the artist depicted the same subject matter across these media. The pictures fall into two groups. The first – almost bucolic in nature – shows the folk traditions and religious customs of the Aymara. The second focuses on the conflict between that traditional way of life and its oppression by various opponents, such as the army, corrupt bureaucrats or wealthy landowners.

Signed lower right: AlejandroMARIOYLLANES

(Illustration no. 2)

Inscribed lower left: retrato(portrait)

Inscribed lower right:

first – almost bucolic in nature – shows the folk traditions and religious customs of the Aymara. The second focuses on the conflict between that traditional way of life and its oppression by various opponents, such as the army, corrupt bureaucrats or wealthy landowners.

As a self-taught artist, Yllanes was from the beginning influenced by the style and colours of the popular arts such as pottery and textiles that he grew up with and which for him embodied the spirit of the Indian people and their close relationship with their land and nature. He thus combined elements from Incan history, the Andean landscape and contemporary Indigenous culture in his compositions and married them with a revolutionary agenda, the struggle for greater rights for the Aymara people. The emphasis was on educating, ennobling and inciting the people. As Salazar Mostajo explained:

“[People] were amazed to see the Indian character so differently portrayed than in traditional painting. In Yllanes’ work the Indian’s back was straight, not hunched. His plowing tools became weapons. He is depicted as a protagonist rather than the servant in the masters’ vestibules. Instead of meekness and fragility, the Indian is shown with the strength ready to explode. Now the impulse is aggressive.”23

How did Yllanes fit into the Bolivian art world at that time? How did he view his position there? The most influential Bolivian artist at the time was Cecilio Guzman de Rojas (1900-1950), who was appointed director of the National Academy of Fine Arts in 1932. Rojas and his followers such as Crespo Gastelu (1901-1947) produced somewhat tender decorative depictions of indigenous life rather than the pressing social issues of the day. As the Latin American Art scholar, Jacqueline Barnitz, notes: “Bolivian representations of Indians as a whole are more allegorical than reflective of contemporary realities.” 24 That makes the achievements of Yllanes all the more remarkable as he stood out among his fellow Bolivians with his brave and relentless commitment to depict the struggles of his time. To do so, he developed his own artistic language that was far removed from the works of Rojas and his students. As Yllanes himself said:

If you consider the few painters that now exist in Bolivia, the majority of them are doing still life, flowers, fruits and saints. I was painting peasants and miners. Certainly, people were disgusted. I brought into my paintings daily scenes in Oruro which I painted with social intention.25

Not surprisingly, Yllanes connected with artists beyond Bolivia. An interview with the artist in the 2 August 1940 edition of the newspaper La Manana reveals that he had held an exhibition in Buenos Aires in 1938 before visiting Santiago, Chile, where he sold two works to the Colombian Embassy for 20,0000 Bs. On the same trip he also spent time in Mexico, where he was able to study the murals of Diego Rivera, Clemente de Orozco (1883-1949) (“the artist I liked most”) and David Alfaro Sequeiros (1896-1974).

In 1941, back in La Paz, Yllanes held an exhibition of paintings and engravings in the Palacio Municipal, a prestigious location. The show received favourable reviews, with one noting that “Mario IIlanes has made notable progress in his drawing, colour and composition.”26 Another highlighted the sheer power of the art, the “formidable belligerence of Yllanes”, who takes up the brush as if “a bomber plane, to make war.”27 Edmundo de Bejar, who wrote on the indigenous art of Warisata, summarised the importance of the artist at that point of his career: “he is quite simply the voice of the indigenous peoples.”28 The exhibition drew vast crowds “from all walks of life”, who were affected by the subject matter that “…opened a very good argument about the sorrowful situation in which the country was trapped.”29

The inflammatory subject matter, however, drew the attention of the rightwing extremists now in the ascendant following the installation in 1940 of a military junta under Carlos Quintanilla (1888-1964) and Colonel Enrique Penaranda (1892-1969), who set about reversing the nationalist reforms of the previous government. There was talk of closing the show early30 and, as Yllanes later recalled, the mayor and council of La Paz objected to the antiimperialist tendencies in his paintings which they “wanted to throw out on the street. General Penanranda gave orders to arrest me. I was kept locked up for days in a dirty jail.” 31

It was his treatment at the hands of the authorities that almost certainly contributed to Yllanes’ decision to travel outside Bolivia in the second half of the 1940s. In September 1944, he held another exhibition of political engravings in La Paz. Once again, the show drew favourable reviews. Manuel Fuentes Lira, a Peruvian artist trained under Guzman de Rojas, writes of the importance to Yllanes of his engravings:

The artist’s idiosyncrasy is identified with the medium which best expresses his interior world: the tragedy, the pain, the torment etc meet their exact cabal tone in the monochrome of the engravings.

But after government critique, he started to set his sights elsewhere. In a rare interview published on the occasion of the exhibition, Yllanes said that because the show happened to be a commercial success, he was able to travel and exhibit abroad.33 He intended to take about 50 works and planned to be away for three to four years, aiming to “win laurels for my country”. Of particular interest are his comments about the National Academy of Arts, which “hasn’t enrolled one student in the 20 plus years it has existed!” Therefore “the majority of artists are self-taught”, producing art that is “our own, original and of the earth. We don’t imitate any European school […] we try to create true Bolivian art, that is, art of the Andes.” The artist’s goal was to travel to Peru, Ecuador, Colombia, Venezuela, Cuba, Mexico and the United States, studying the art of all the places to be visited.

In 1945 Yllanes undertook the trip. The itinerary was in reality less extensive, but he nonetheless visited Peru, Ecuador and Mexico before heading to the United States in 1946. In the first half of the year, the artist held exhibitions in Puno, Arequipa, Lima and Cuzco, Peru and in Quito, Ecuador. All were widely acclaimed and stand as a testament to Yllanes’ growing reputation in Latin America, as can be seen in the numerous reviews and articles that accompanied the shows.34

In each venue, there was a strong sense of brotherhood and shared values between the host nation and the peripatetic artist from Bolivia. At the opening of the show in Cuzco, held under the auspices of the Instituto Americano de Arte, an address given by Edgardo Diaz highlighted how Yllanes’ works serve as “…the strong voices of the spiritual unity of our America, the patrimonial bond of our race which grew up Andean and cosmically in Bolivia, Peru and Mexico.”35 Yllanes’s art was feted throughout Peru. He is described as “the chief exponent of Bolivian painting” and “one of the four greatest engravers in the world, worthy of comparison with Gustave Doré for his wonderful technique and expressivity.”36 It is recorded that there were sales of works: in Cuzco several engravings were acquired by the Instituto Americano de Arte and distinguished locals. The artist also received official recognition. In March, he was named Honorary Member of the Society of Fine Arts of Cuzco and the following month in Lima he was given the title Associate of the Fine Art Society of Peru. There was often a sense of occasion at the openings.

Instituto Americano de Arte and distinguished locals.37 The artist also received official recognition. In March, he was named Honorary Member of the Society of Fine Arts of Cuzco and the following month in Lima he was given the title Associate of the Fine Art Society of Peru. There was often a sense of occasion at the openings. The program of the inauguration in Arequipa on 24 March, for example, included poetry readings and musical recitals alongside several formal addresses, all in the presence of the Bolivian consul to Peru (fig. 4).38

One of the many articles published at that time is of particular interest for it reveals a rare piece of information about Yllanes’ personal life, that he was married to Maria Frontaura Argandoña (1910-1979), an important pedagogue who contributed to Peruvian dairies and magazines with sociological studies on the native American in relationship to problems of pedagogy in the Americas.39 Beyond that, we do not know how or where they met. A group photograph (fig. 5) from the exhibition in Lima published in LaPrensain April 1945 shows Yllanes standing tall above the other attendees, corresponding to Prats’ description of him in the 1946 interview: “an exceptionally tall man, with an air of energetic simplicity, mestizo, thirty-three years of age.”40

In 1945, Yllanes was appointed cultural attaché to the Bolivian Embassy in Mexico,41 travelling there under the auspices of the Bolivian government to study Mexican muralism. The artist’s views on the country were made clear in the 1946 interview with Prats.42 Although he believed that both countries shared the same social and political problems, he noted a fundamental difference:

From the artistic point of view, Mexico has an extraordinary fascination mainly because the Mexican artist could express freely his ideas on the wall of public buildings, a thing that in Bolivia and in other countries in the South, is impossible. The social castes, which dominate in Latin America, are not as liberal as the ones in Mexico.43

From 26 June to 10 July, Yllanes held a solo exhibition at Palacio de Bellas Artes, Mexico City, sponsored by the Secretary of Public Education of Mexico, as well as Rivera, Orozco and Siqueiros. In his preface to the exhibition, Rivera wrote:

The artists and the workers of Mexico ought to welcome our Bolivian Comrade, Yllanes with open arms. May the intellectuals, and also the few artists who take refuge here in a “purist” art (so that they might hide their true sentiments and take care not to antagonise their wealthy clients) look to the example of this Bolivian, who was tortured, endured prison, and suffered exile for the revolutionary affirmation he expressed.44

Such words reveal the respect Rivera held for the younger artist. As in Peru, Yllanes received great acclaim. He was awarded the Gold Medal in Mexico, named an Honorary Guest of the Republic of Mexico and offered a Diploma of “Proven Merit” by the President of the Republic of Mexico, Manuel Avila Camacho (1897-1955).

In the interview with Prats, Yllanes stated that he intended to travel to the United States after Mexico “in order to paint scenes of North American industrial life and the life of its crowds and its workers.”45 In that way, he would be able to study murals depicting the manufacturing sector that were painted there by the Mexican artists, and that would then allow him to learn about the struggle of the proletariat in a different political context.

In 1946, Yllanes emigrated to New York. Two graphic works were acquired by the Brooklyn Museum in 1947 and on 23 December of that year he signed an application form for a Guggenheim Fellowship Grant, his address given as 545 W 111 St. The form itself contains some interesting biographical information and sets out the artist’s proposed project:

information and sets out the artist’s proposed project: “a careful study of the art of North American Indians in comparison with that of the South American Indian …” with the goal of “announcing the principal theories which can serve as a foundation for the Art of the Americas.”46 He was awarded the Fellowship but never collected the funds.

After that point it is not clear what happened to Yllanes. He appeared in the 1948 edition of Who’s Who in American Art and continued to be until 1972. However, in a short entry in BolivianPaintersofthe20thCentury , published in La Paz in 1989, it is recorded that he died in Mexico in 1960. It is possible that his revolutionary ideas made him a political target. As Combalía suggests, America may not have been such a tolerant place with its witch hunts against those suspected of Communist leanings beginning in 1947. Nor would Yllanes have felt welcomed back in Bolivia, which in 1946 had entered a state of civil war that was to last until 1952. On that basis, it seems plausible that he could have returned to Mexico.

While it is not possible to establish with any certainty Yllanes’ whereabouts after 1948, we do, however, know that he left a large body of work in New York, which was acquired en bloc in 1978 by the American collectors Mr and Mrs Edward Ford. Since then, Yllanes’ name has not been entirely forgotten. In 1992, two exhibitions of his work were held. The first – organized by Nicholas Clemente at the Ben Shahn Galleries at William Patterson College in Wayne, New Jersey – focused on the artist’s graphic production. The second was a major retrospective organized by the Edith C. Blum Art Institute at Bard College in Annandale-on-Hudson, New York: Being Rediscovered:TheSpanishConquestfromtheAmer-IndianPointofView. AndeanCultureandthelifeofAlejandroMario Yllanes. Curated by Linda Weintraub, the show was accompanied by a series of Andean cultural events (lectures, concerts and films) and a seminar on Yllanes’ art. The exhibition received a favourable review in the New York Times. In 2016, the artist’s extant body of work was published for the first time in a catalogue raisonné, MarioAlejandroYllanes(1913-1946) , by the Martin du Louvre Gallery in Paris, and his work was re-assessed by Combalía in the essay DiscoveringMario AlejandroYllanes . The present exhibition at Ben Elwes Fine Art in London, allows audiences in Europe to see Yllanes’ remarkable art for the first time.

1. Recorded in a letter sent from Hotel Paris to LaPaz , 4 September 1933.

2. The article is entitled “Pintura de la nueva Bolivia. La obra fascinante y dramática de Mario Alejandro Yllanes”, published in Hoy , Mexico City, 13 July 1946, p. 62. It will be referred to in the present article as Prats, 1946.

3. Published in LaPaz , 1989. This work is often referred to in the research material held in the archives at Bard for their 1992 exhibition.

4. The archives at Bard College contain a large amount of material compiled for research purposes only and thus never published. It contains many interesting and insightful discussions about the artist and his life. We are thankful to Bard College for granting access to this material. It will be referred to in this essay as Bard, 1992.

5. We gratefully acknowledge all these sources in writing this essay.

6. The name is also written Illanes.

7. The early years of his life are recorded in Prats, 1946.

8. Published in a newspaper dated 6 July 1930. Lafuente explained how Yllanes drew female silhouettes and caricatures in his notebooks, until he found a personal idiom, one based on “regional art”. He went on to predict that his friend would become “the artist of the land, of the race” and commended him for his modesty.

9. Mythological works contained symbols used in the Tiahuanacu empire (LaCrónica , 10 August 1930).

10. As noted in the various reviews that form part of the Bard material. The sales are recorded in VidaSocial , Oruro, 21 August 1930.

11. The war was fought over the control of the Gran Chaco area on the border between the two countries which was thought to be rich in oil.

12. LaCrónica , 11 April 1945.

13. LaRazon , 17 September 1933.

14. Recorded in a letter sent from Hotel Paris to La Paz, 4 September 1933.

15. It was known as the Ayllu School. Aylluwas a word in Aymara referring to a network of families in a particular area.

16. LapedagogiahechaedificioenWarisata.Uncapitulodearquitecturaescolarenel TercerMundo,La Paz, 1989 (Publicaccion inedita de I.N.S.B.O.L.). Quoted in Bard 1992, p. 17.

17. Op.cit.; quoted in Bard, 1992, p. 19.

18. Prats, 1946: “Nobody appeared to be paying the least attention to my art when it occurred to the Peruvian writer Uriel Gacia to give a talk about it in La Paz. The outcome was the destruction of the murals.”

19. Prats, 1946.

20. Op.cit.; quoted in Bard, 1992, p. 5.

21. See, for example, SombraEterna(EternalShadow)(1941) in which two young lovers contemplate their shadows which are transformed into skeletons, or HoraMaldita (AccursedGallows)(1944).

22. Yllanes also produced sculptures, although no extant works survive.

23. Op.cit.; quoted in Bard, 1992, p. 6.

24. J. Barnitz, Twentieth-CenturyartofLatinAmerica , Texas, 2001, p. 101.

25. Prats, 1946.

26. Unnamed newspaper, 6 February 1941.

27. “El Arte de AMI” in an unnamed newspaper, 16 February 1941.

28. INTI, 11 February 1941.

29. Paraphrased from “Movement of the popular elite to see the paintings of Mario Yllanes” in LaCrónicanewspaper, 12 February 1941; quoted in Bard, 1992, p. 20.

30. As reported in an unnamed newspaper article, 14 February 1941.

31. Prats, 1946. Interestingly, Combalía refers to another proposed exhibition by Yllanes (op. cit.,p. 27) that was cancelled by the authorities, which reinforces the impression that he was being monitored by the government.

32. UltimaHora , 5 October 1944.

33. UltimaHora , 5 October 1944.

34. As can be seen in the numerous press reviews in the Bard archive of press clippings.

35. ElCommercio , 23 February 1945.

36. Noticias , 20 March 1945.

37. ElSol , 8 March 1945.

38. The program also includes a list of works exhibited: 12 mural paintings and 20 engravings.

39. LaPuebla , Arequipa, 15 March 1945.

40. Prats, 1946.

41. This date is given by the artist in his application for a Guggenheim Fellowship in 1947 (see below).

42. In the interview, Yllanes reveals that he had started painting his own murals before he became aware of the work of the Mexicans in 1936 (through prints and reproductions in books).

43. Prats, 1946.

44. Prats, 1946.

45. Prats, 1946.

46. For example, he received a grant in 1945 from the government of Bolivia for “Studies at the Institute of Technology, Testing of Painting Materials Section.” It also lists museums which owned his works. Interestingly his wife’s name is given as Maria Frontaura de Illanes-La Paz, rather than the Maria Frontaura Argandoña of the 1944 article (see above). She is also listed as residing in Bolivia, i e., she did not accompany her husband to the USA.

47. Op.cit., p. 30.

48. Vivien Raynor, “Works by a Vanished Bolivian Painter”, NewYorkTimes , 5 April 1992.

OffrendaaINTI

Ink and graphite on paper

16 x 12 cm

Signed: AMY

(Illustration no. 28)

Ben Elwes Fine Art, London Art Week, Summer 2023

30 June – 7 July

List of illustrations:

1. WakhaThokhoriArando , 1937 (detail on back cover)

2. Wakha-YKhusillo,1937 (also illustrated p. 22)

3. LakeTiticaca,1935 (illustrated p. 1 and 7, detail on cover)

4. KhenasKhenas,1937

5. EstañoMaldito,1937 (illustrated p. 9-10)

6. VivaLaGuerra , 1938 (illustrated p. 3)

7. TragediadelPongo,1932 (illustrated p. 12)

8. Self-portrait , 1944 (also illustrated p. 23)

9. Self-portrait,1941 (illustrated p. 15)

10. HoraMaldita , 1944

11. StudyforHoraMaldita

12. Elegia,1944

13. Trincheras,1944

14. Funeral , 1944

15. Aguadorcito

16. Lakita , 1944

17. SombraEterna(EternalShadow),1941

18. Vision

19. StudyforVision

20. MuertadeWilka,1941

21. SkullandLlama

22. Parias,1941

23. Llockalla , 1944

24. PuebloAymara

25. PatioAymara , 1941

26. 7deJunio , 1939

27. ManwithSeveredHands , 1941

28. OffrendaaINTI(illustrated p. 32)

29. GolgothaAymara

30. DeitywithSeveredHeads

31. StandingDeitywithOutstretchedArms

32. Wilka

33. PortraitofDiegoRivera(illustrated p. 13)

34. RitualDance

35. Warisata

36. MusicaTriste

37. Pieta

38. Challweras

WakhaThokhoriArando

1937

Oil on canvas

142 x 197 cm (56 x 77 ½ in)

Signed lower right: AlejandroMARIOYLLANES

Wakha-YKhusillo

1937

Oil on canvas

142 x 197 cm (56 x 77 ½ in)

Signed lower right: AlejandroMARIOYLLANES

KhenasKhenas

1937

Oil on canvas

127 x 208.3 cm (50 x 82 in)

Signed lower left:alejandroMARIOYLLANES

Self-portrait 1944

Wood engraving 25 x 18 cm (9 4/5 x 7 in)

Inscribed lower left: retrato(portrait)

Inscribed lower right: grab.cimp.pora/a.m.Yllanes/caso/44

1944

Wood Engraving

36 x 46 cm (14 1/5 x 18 in)

Inscribed lower left: elegia

Inscribed lower right: Yllanes

Trincheras 1944

Wood engraving

28 x 40 cm (11 x 15 ¾ in)

Inscribed lower left: trinchera(French–ofBoliviaandParaguaywar –CHACO)

Inscribed lower right: grab. eimp.pora/a.mYllanes/caso/44

Funeral 1944

Wood engraving

48 x 20 cm (18 9/10 x 7 4/5 in)

Inscribed lower left: funeral(AymaraIndianGods+Micology)

Inscribed lower right: greimp.por/a.m.Yllanes/caso/44

Aguadorcito

1944

Wood engraving

36 x 28 cm (14 1/5 x 11 in)

Inscribed lower left: aguadorcito– watercarrier

Inscribed lower right: grab.eimp.por/a.m.Yllanes/caso/44

Lakita

1944

Wood engraving

40 x 28 cm (15 ¾ x 11 in)

Inscribed lower left: Lakita

Inscriber lower right: grab.eimp.por/a.m.Yllanes/Caso/44

SombraEterna(EternalShadow)

1941 Wood engraving

41 x 28 cm (16 1/5 x 11 in)

Inscribed lower left: sombraeterna(eternalshadow)

Inscribed lower right: engrav.By/a.m.Yllanes/41

MuertedeWillka

1941

Wood engraving

28 x 40 cm (11 x 15 ¾ in)

Inscribed lower left: muertedewillka

Inscribed lower right: grabeimp.por/amYllanes/caso/41

Parias

1941

Wood engraving

36 x 28 cm (14 1/5 x 11 in)

Inscribed lower left: beggars

Inscribed lower right: woodcutby/a.m.Yllanes/41

Llockalla

1944

Wood engraving

40 x 22 cm (15 ¾ x 8 3/5 in)

Inscribed lower left: Llockalla–boy

Inscribed lower right: grab.eimppor/a.m.Yllanes/caso/44

25

PatioAymara

1941

Wood engraving

28 x 40 cm (11 x 15 ¾ in)

Inscribed lower left: patioAymara

Inscribed lower right: grab.eimp.por/a.mYllanes/caso/41

ManwithSeveredHands

1941

Lithograph

38 x 50 cm (15 x 19 3/5 in)

Signed lower left: Yllanes

GolgothaAymara

Graphite and charcoal on paper

34 x 39 cm (13 2/5 x 15 2/5 in)

Signed lower left: MarioYllanes

MusicaTriste

Challweras 1932

“El Arte de AMI” in an unnamed newspaper, 16 February 1941. (Alejandro Mario Yllanes Archive).

“El Arte Revolucionario de M.A. Illanes,” Inti , Feb. 11, 1941. (Alejandro Mario Yllanes Archive).

“La exposición del artista Illanes,” LaCrónica(Oruro), Aug. 1, 1930. (Alejandro Mario Yllanes Archive).

“La Exposición Illanes,” ElDiario , Sept. 15, 1933. (Alejandro Mario Yllanes Archive).

“La pedagogia hecha edificio en Warisata. Un capitulo de arquitectura escolar en el Tercer Mundo”, LaPaz , 1989 (Publicaccion inedita de I.N.S.B.O.L.).

“Pintura de la nueva Bolivia. La obra fascinante y dramática de Mario Alejandro Yllanes”, Hoy , Mexico City, 13 July 1946.

“Mario Illanes Estuvo en México, Chile y la Argentina,” Inti , Aug. 2, 1940. (Alejandro Mario Yllanes Archive).

“Movimiento de la Elite Popular para ver la exposición pictórica de Mario Illanes,” LaCrónica , Feb. 12, 1941. (Alejandro Mario Yllanes Archive).

“Un Formidable Ensayo Educacional: Visita la Escuela indigenal de Huarizata,” Feb. 1, 1934. (Alejandro Mario Yllanes Archive).

Bosshard, Marco Thomas. Warisata en al arte, la literatura y la política boliviana: Observaciones acerca del impacto de la Escuela-Ayllu en la producción artística boliviana y la nueva legislación educativa del gobierno de Evo Morales,” BolivianStudiesJournal , v. 15-17, 2008-2010: 64-90.

ElCommercio , 23 February 1945. (Alejandro Mario Yllanes Archive).

ElSol , 8 March 1945. (Alejandro Mario Yllanes Archive).

Haya de la Torre, Víctor Raúl. “Diego Rivera,” Amauta 1: 4, 1926.

LaCrónica,11 April 1945. (Alejandro Mario Yllanes Archive).

LaPuebla , Arequipa, 15 March 1945. (Alejandro Mario Yllanes Archive).

LaRazon , 17 September 1933. (Alejandro Mario Yllanes Archive).

Larson, Brooke. “Warisata: A Historical Footnote,” ReVista: Harvard Review of Latin America, Fall 2011, XI: 1, https://revista.drclas.harvard.edu/warisata/

Noticias , 20 March 1945. (Alejandro Mario Yllanes Archive).

Pavletich, Esteban. “Diego Rivera: El artista de una clase,” Amauta 1: 5, 1927: 5-9.

Prats, Alardo. “Pintura de la Nueva Bolivia: La obra fascinante y dramática de Alejandro Mario Yllanes,” Hoy , July 3, 1936: 62. (Alejandro Mario Yllanes Archive).

Raynor. Vivien, “Works by a Vanished Bolivian Painter”, NewYorkTimes , 5 April 1992.

Salazar de la Torre, Cecilia. “Estetica y política en la escuela-Ayllu de Warisata: Una aproximación al expresionismo de Mario Alejandro Illanes,”Allpanchis, 68 (2006): 175-196.

UltimaHora , 5 October 1944. (Alejandro Mario Yllanes Archive).

Untitled article, Inti , Feb. 15, 1941. (Alejandro Mario Yllanes Archive).

VidaSocial , Oruro, 21 August 1930. (Alejandro Mario Yllanes Archive).

Villarroel Claure, R. “Un pintor original,” ElDiario , Sept. 12, 1933. (Alejandro Mario Yllanes Archive).

Yllanes, Alejando Mario. “Petition to John Simon Guggenheim Memorial Foundation,” 1946